Battle of Austerlitz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important military engagements of the

Napoleon hoped that the Allied forces would attack, and to encourage them, he deliberately weakened his right flank. On 28 November, Napoleon met with his marshals at Imperial Headquarters, who informed him of their qualms about the forthcoming battle. He shrugged off their suggestion of retreat.

Napoleon's plan envisaged that the Allies would throw many troops to envelop his right flank to cut the French communication line from

Napoleon hoped that the Allied forces would attack, and to encourage them, he deliberately weakened his right flank. On 28 November, Napoleon met with his marshals at Imperial Headquarters, who informed him of their qualms about the forthcoming battle. He shrugged off their suggestion of retreat.

Napoleon's plan envisaged that the Allies would throw many troops to envelop his right flank to cut the French communication line from

albeit disputed

episode occurred during this retreat: defeated Russian forces withdrew south towards Vienna via the frozen Satschan ponds. French artillery pounded towards the men, and the ice was broken by the bombardment. The fleeing men drowned in the cold ponds, dozens of Russian artillery pieces going down with them. Estimates of how many guns were captured differ: there may have been as few as 38 or more than 100. Sources also differ about casualties, with figures ranging between 200 and 2,000 dead. Many drowning Russians were saved by their victorious foes. However, local evidence later made public suggests that Napoleon's account of the catastrophe may have been exaggerated; on his instructions, the lakes were drained a few days after the battle and the corpses of only two or three men, with some 150 horses, were found. On the other hand, Tsar Alexander I attested to the incident after the wars.

Artists and musicians on the side of France and her conquests expressed their sentiments in the popular and elite art of the time. Prussian music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann, in his famous review of Beethoven's 5th Symphony,

Artists and musicians on the side of France and her conquests expressed their sentiments in the popular and elite art of the time. Prussian music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann, in his famous review of Beethoven's 5th Symphony,

Napoleon did not succeed in defeating the Allied army as thoroughly as he wanted, but historians and enthusiasts alike recognize that the original plan provided a significant victory, comparable to other great tactical battles such as

Napoleon did not succeed in defeating the Allied army as thoroughly as he wanted, but historians and enthusiasts alike recognize that the original plan provided a significant victory, comparable to other great tactical battles such as

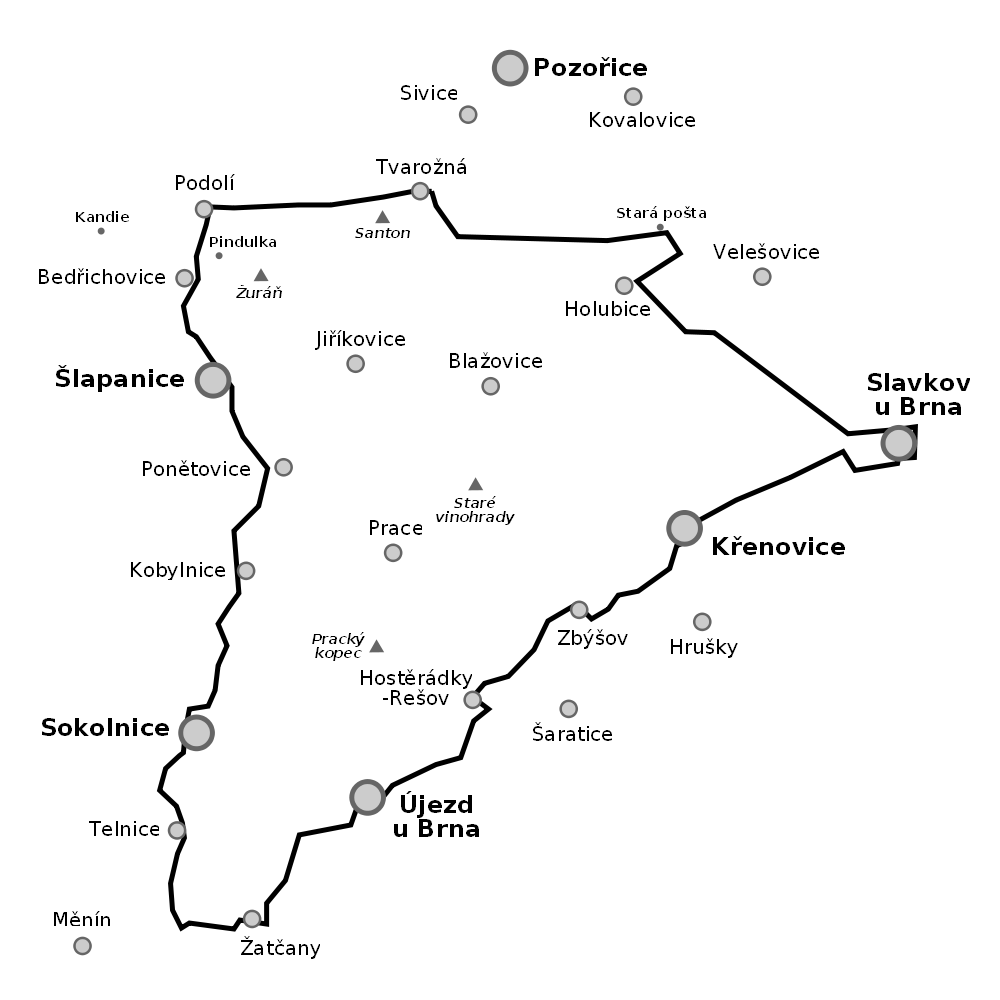

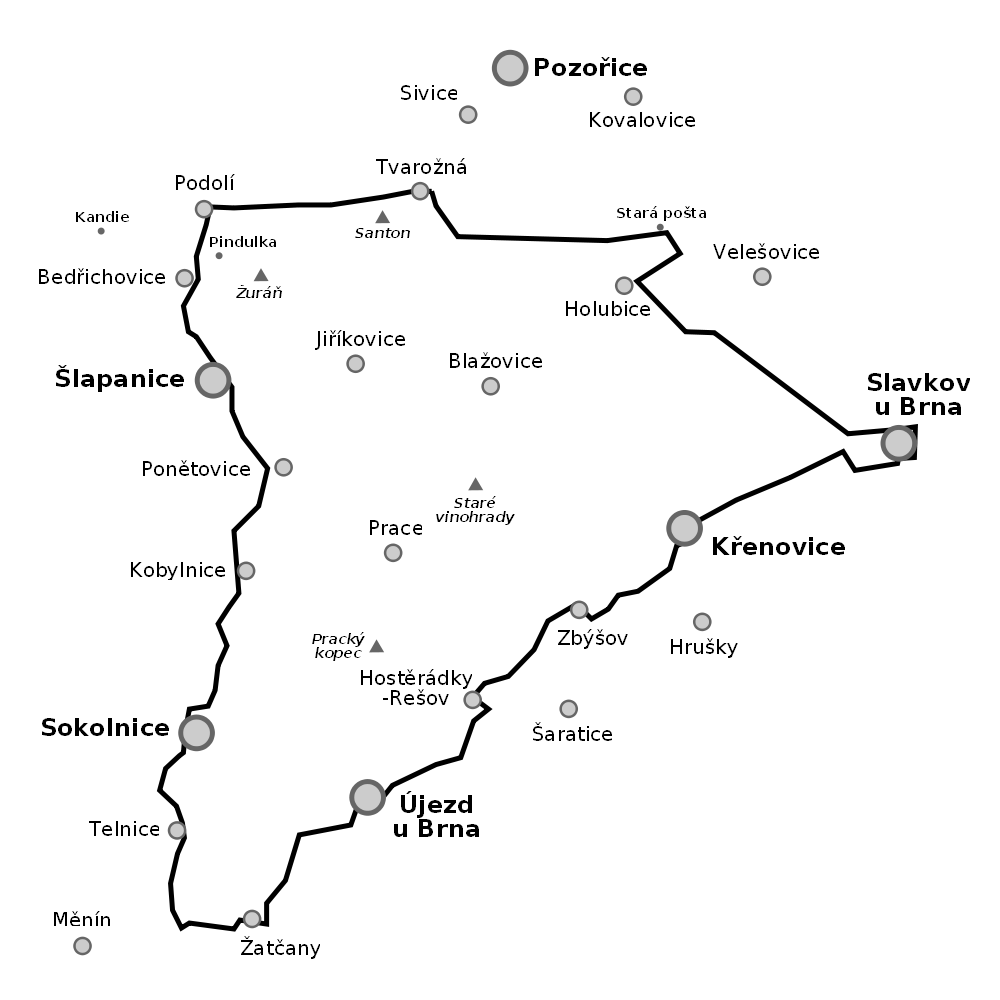

In the years following the battle, many memorials were set up around the affected villages to commemorate both the individual episodes of the battle and the thousands of its victims. Since 1992, the area where the Battle of Austerlitz took place has been protected by law as a landscape monument zone. Its value lies in the historical peculiarities of the place, the historical connections of settlements, landscapes and terrain formations, and the overall landscape image. The area extends to 19 of today's

In the years following the battle, many memorials were set up around the affected villages to commemorate both the individual episodes of the battle and the thousands of its victims. Since 1992, the area where the Battle of Austerlitz took place has been protected by law as a landscape monument zone. Its value lies in the historical peculiarities of the place, the historical connections of settlements, landscapes and terrain formations, and the overall landscape image. The area extends to 19 of today's

Austerlitz order of battle

*

*

Austerlitz 2005: la bataille des trois empereurs

*

''Austerlitz Online Game''

(Pousse-pion éditions, 2010) * (Napoleonic Miniatures Wargame Society of Toronto) * *

View on battle place – virtual show

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Austerlitz 1805 Battles commanded by Napoleon 1805 in France 1805 in the Austrian Empire Conflicts in 1805 Battles in Moravia Battles of the War of the Third Coalition involving Austria Battles of the War of the Third Coalition involving Russia Battles involving the Kingdom of Italy (Napoleonic) Czech lands under Habsburg rule December 1805 Vyškov District Battles inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe History of the South Moravian Region Joachim Murat Battles of the Napoleonic Wars involving Liechtenstein

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

(now Slavkov u Brna

Slavkov u Brna (; ) is a town in Vyškov District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,300 inhabitants. The town gave its name to the Battle of Austerlitz, which took place several kilometres west of the town. The his ...

in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

). Around 158,000 troops were involved, of which around 24,000 were killed or wounded.

The battle is often cited by military historians as one of Napoleon's tactical masterpieces, in the same league as other historic engagements like Hannibal

Hannibal (; ; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Punic people, Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Ancient Carthage, Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's fat ...

's Cannae

Cannae (now , ) is an ancient village of the region of south east Italy. It is a (civil parish) of the (municipality) of . Cannae was formerly a bishopric, and is a Latin Catholic titular see (as of 2022).

Geography

The commune of Cannae i ...

(216 BC) or Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

's Gaugamela (331 BC). Farwell p. 64. "Austerlitz is generally regarded as one of Napoleon's tactical masterpieces and has been ranked as the equal of Arbela, Cannae, and Leuthen." Dupuy p. 102 Note: Dupuy was not afraid of expressing an opinion, and he classified some of his subjects as Great Captains, such as Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. The military victory of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's at Austerlitz brought the War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition () was a European conflict lasting from 1805 to 1806 and was the first conflict of the Napoleonic Wars. During the war, First French Empire, France and French client republic, its client states under Napoleon I an ...

to an end, with the Peace of Pressburg signed by the French and Austrians later in the month. These achievements did not establish a lasting peace on the continent. Austerlitz had driven neither Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

nor Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, whose armies protected Sicily from a French invasion, to settle. Prussian

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

resistance to France's growing military power in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

led to the War of the Fourth Coalition

The War of the Fourth Coalition () was a war spanning 1806–1807 that saw a multinational coalition fight against Napoleon's First French Empire, French Empire, subsequently being defeated. The main coalition partners were Kingdom of Prussia, ...

in 1806.

After eliminating an Austrian army during the Ulm campaign

The Ulm campaign was a series of French and Bavarian military maneuvers and battles to outflank and capture an Austrian army in 1805 during the War of the Third Coalition. It took place in the vicinity of and inside the Swabian city of Ulm. ...

, French forces seized Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

in November 1805. The Austrians avoided further conflict until the arrival of the Russians, who helped increase the allied numbers. Napoleon sent his army north in pursuit of the Allies but then ordered his forces to retreat so he could feign a grave weakness to lure the Allies into thinking that they were facing a weak army, while it was in fact formidable. Napoleon gave every indication in the days preceding the engagement that the French army was in a pitiful state, even abandoning the dominant Pratzen Heights near Austerlitz. He deployed the French army below the Pratzen Heights and weakened his right flank, enticing the Allies to launch an assault there to roll up the French line. A forced march from Vienna by Marshal Davout and his III Corps plugged the gap left by Napoleon just in time. The Allied deployment against the French right weakened the Allied centre on the Pratzen Heights, which was attacked by the IV Corps of Marshal Soult

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, 1st Duke of Dalmatia (; 29 March 1769 – 26 November 1851) was a French general and statesman. He was a Marshal of the Empire during the Napoleonic Wars, and served three times as President of the Council of ...

. With the Allied center demolished, the French swept through both flanks and routed the Allies, which enabled the French to capture thousands of prisoners.

The Allied disaster significantly shook the will of Emperor Francis to further resist Napoleon. France and Austria agreed to an armistice immediately, and the Treaty of Pressburg followed shortly after, on 26 December. Pressburg took Austria out of both the war and the Coalition while reinforcing the earlier treaties of Campo Formio and of Lunéville between the two powers. The treaty confirmed the Austrian loss of lands in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

to France, and in Germany to Napoleon's German allies. It also imposed an indemnity of 40 million francs on the Habsburgs and allowed the fleeing Russian troops free passage through hostile territories and back to their home soil. Critically, victory at Austerlitz permitted the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine or Rhine Confederation, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austrian Empire, Austria ...

, a collection of German states intended as a buffer zone between France and the eastern powers, Austria, Prussia and Russia. The Confederation rendered the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

virtually useless, so Francis dissolved the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, but remained as emperor of Austria. These achievements failed to establish a lasting peace on the continent. Prussian

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

worries about the growing French influence in Central Europe led to the War of the Fourth Coalition

The War of the Fourth Coalition () was a war spanning 1806–1807 that saw a multinational coalition fight against Napoleon's First French Empire, French Empire, subsequently being defeated. The main coalition partners were Kingdom of Prussia, ...

in 1806.

Background

Europe had been in turmoil since the start of theFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

in 1792. In 1797, after five years of war, the French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

subdued the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that succeeded it. They were only loosely allied ...

, an alliance of Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, Spain, and various Italian states. A Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition () (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war targeting revolutionary France by many European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria, and Russia and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, ...

, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Portugal and the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, was formed in 1798, but by 1801, this too had been defeated, leaving the British the only opponent of the new French Consulate

The Consulate () was the top-level government of the First French Republic from the fall of the French Directory, Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 9 November 1799 until the start of the First French Empire, French Empire on 18 May 1804.

...

. In March 1802, France and Britain agreed to end hostilities under the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France, the Spanish Empire, and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set t ...

.

However, many problems persisted between the two sides, making implementation of the treaty increasingly difficult. The British government resented having to return the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

and most of the Dutch West Indies to the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic (; ) was the Succession of states, successor state to the Dutch Republic, Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 after the Batavian Revolution and ended on 5 June 1806, with the acce ...

. Napoleon was angry that the British refused to abandon the island of Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

. The tense situation only worsened when Napoleon sent an expeditionary force to restore French authority and slavery in Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

. In May 1803, Britain declared war on France.

Third Coalition

In December 1804, an Anglo-Swedish agreement led to the creation of the Third Coalition. British Prime MinisterWilliam Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, p ...

spent 1804 and 1805 in a flurry of diplomatic activity geared towards forming a new coalition against France, and by April 1805, Britain and Russia had signed an alliance. Having been defeated twice in recent memory by France and being keen on revenge, Austria joined the Coalition a few months later.

Forces

French Imperial army

Before the formation of the Third Coalition, Napoleon had assembled an invasion force called the ''Armée d'Angleterre'' (Army of England) around six camps atBoulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

in Northern France. He intended to use this force, amounting to 150,000 men, to strike at England and was so confident of success that he had commemorative medals struck to celebrate the conquest of the English. Although they never invaded, Napoleon's troops received careful and invaluable training for any possible military operation. Boredom among the troops occasionally set in, but Napoleon paid many visits and conducted lavish parades to boost morale.

The men at Boulogne formed the core for what Napoleon would later call . The army was organized into seven corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

, which were large field units that contained 36 to 40 cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

s each and were capable of independent action until other corps could come to their aid. A single corps (adequately situated in a solid defensive position) could survive at least a day without support. In addition to these forces, Napoleon created a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

reserve of 22,000 organized into two cuirassier

A cuirassier ( ; ; ) was a cavalryman equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as man-at-arms, men-at-arms and demi-lancers discarding their ...

divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

, four mounted dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat wi ...

divisions, one division of dismounted dragoons and one of light cavalry, all supported by 24 artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

pieces. By 1805, the had grown to a force of 350,000 men, who were well equipped, well trained, and led by competent officers.

Russian Imperial army

The Russian army in 1805 had many characteristics ofAncien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

organization. There was no permanent formation above the regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

al level, and senior officers mostly belonged to aristocratic circles. The Russian infantry was considered one of the hardiest in Europe, with fine artillery crewed by experienced professional soldiers.

Austrian Imperial army

Archduke Charles, brother of the Austrian Emperor, had started to reform the Austrian army in 1801 by taking away power from the , the military-political council responsible for the armed forces. Charles was Austria's most able field commander, but he was unpopular at court and lost much influence when, against his advice, Austria decided to go to war with France. Karl Mack became the new main commander in Austria's army, instituting reforms on the eve of the war that called for a regiment to be composed of fourbattalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

s of four companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

, rather than three battalions of six companies.

Preliminary moves

In August 1805, Napoleon,Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First French Empire and the Second French Empire. The emperor of France was an absolute monarch.

Details

After rising to power by ...

since December of the previous year, turned his sights from the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

to the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

to deal with the new Austrian and Russian threats. On 25 September after a feverish march in great secrecy, 200,000 French troops began to cross the Rhine on a front of . Mack had gathered the greater part of the Austrian army at the fortress of Ulm in Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

.

Napoleon swung his forces southward in a wheeling movement that put the French at the Austrian rear while launching cavalry attacks through the Black Forest

The Black Forest ( ) is a large forested mountain range in the States of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is th ...

, which kept the Austrians at bay. The Ulm Maneuver was well-executed, and on 20 October, 23,000 Austrian troops surrendered at Ulm, bringing the number of Austrian prisoners of the campaign to 60,000. Although this spectacular victory was soured by the defeat of a Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar the following day, French success on land continued as Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

fell in November. The French gained 100,000 muskets, 500 cannons, and intact bridges across the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

.

Russian delays prevented them from saving the Austrian armies; the Russians withdrew to the northeast to await reinforcements and link up with surviving Austrian units. Tsar Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon from 495 to 454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas, ruler of the Seleucid Empire 150-145 BC

* Pope Alex ...

appointed general Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov commander-in-chief of the combined Russo-Austrian force. On 9 September 1805, Kutuzov arrived at the battlefield, quickly contacting Francis I of Austria

Francis II and I (; 12 February 1768 – 2 March 1835) was the last Holy Roman Emperor as Francis II from 1792 to 1806, and the first Emperor of Austria as Francis I from 1804 to 1835. He was also King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, and served ...

and his courtiers to discuss strategy and logistics. Under pressure from Kutuzov, the Austrians agreed to supply munitions and weapons promptly. Kutuzov also spotted shortcomings in the Austrian defense plan, which he called "very dogmatic". He objected to the Austrian annexation of the land recently under Napoleon's control because this would make the local people distrust the allied force.

The French followed after Kutuzov but soon found themselves in a difficult position. Prussian intentions were unknown and could be hostile; the Russian and Austrian armies had converged, and French lines of communication were extremely long, requiring strong garrisons to keep them open. Napoleon realized that to capitalize on the success at Ulm, he had to force the Allies to battle and then defeat them.

On the Russian side, Kutuzov also realized Napoleon needed to do battle, so instead of clinging to the "suicidal" Austrian defense plan, Kutuzov decided to retreat. He ordered Pyotr Bagration to contain the French at Vienna with 600 soldiers. He instructed Bagration to accept Murat's ceasefire proposal so the Allied Army could have more time to retreat. It was later discovered that the proposal was false and had been used to launch a surprise attack on Vienna. Nonetheless, Bagration held off the French assault for a time by negotiating an armistice with Murat, thereby providing Kutuzov time to position himself with the Russian rearguard near Hollabrunn

Hollabrunn () is a district capital town in the Austrian state of Lower Austria, on the Göllersbach river. It is situated in the heart of the biggest wine region of Austria, the Weinviertel.

History

The surroundings of Hollabrunn were firs ...

.

Murat initially refrained from an attack, believing the entire Russian army stood before him. Napoleon soon realized Murat's mistakes and ordered him to pursue quickly, but the allied army had already retreated to Olmütz. According to Kutuzov's plan, the Allies would retreat further to the Carpathian

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe and Southeast Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at ...

region and "at Galicia, I will bury the French."

Napoleon did not stay still. The French Emperor decided to set a psychological trap to lure the Allies out. Days before any fighting, Napoleon had been giving the impression that his army was weak and desired a negotiated peace. About 53,000 French troops—including Soult, Lannes, and Murat's forces—were assigned to take Austerlitz and the Olmütz road, occupying the enemy's attention. The Allied forces, numbering about 89,000, seemed far superior and would be tempted to attack the outnumbered French army. However, the Allies did not know that Bernadotte, Mortier and Davout were already within supporting distance and could be called in by forced marches -- Bernadotte from Iglau, and Mortier and Davout from Vienna -- which would raise the French number to 75,000 troops.

Napoleon's lure did not stop at that. On 25 November, General Savary was sent to the Allied headquarters at Olmütz to deliver Napoleon's message, expressing his desire to avoid a battle while secretly examining the Allied forces' situation. As expected, the overture was seen as a sign of weakness. When Francis I offered an armistice on the 27th, Napoleon accepted enthusiastically. On the same day, Napoleon ordered Soult to abandon both Austerlitz and the Pratzen Heights and, while doing so, to create an impression of chaos during the retreat that would induce the enemy to occupy the Heights.

The next day (28 November), the French Emperor requested a personal interview with Alexander I. He received a visit from the Tsar's most impetuous aide, Prince Peter Dolgorukov. The meeting was another part of the trap, as Napoleon intentionally expressed anxiety and hesitation to his opponents. Dolgorukov reported an additional indication of French weakness to the Tsar.

The plan was successful. Many Allied officers, including the Tsar's aides and the Austrian Chief of Staff Franz von Weyrother, strongly supported an immediate attack and appeared to sway Tsar Alexander. Kutuzov's plan to retreat further to the Carpathian

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe and Southeast Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at ...

region was rejected, and the Allied forces soon fell into Napoleon's trap.

Battle

The battle began with the French army outnumbered. Napoleon had some 72,000 men and 157 guns for the impending battle, with about 7,000 troops under Davout still far to the south in the direction of Vienna. The Allies had about 85,000 soldiers, seventy percent of them Russian, and 318 guns. At first, Napoleon was not confident of victory. In a letter written to Minister of Foreign Affairs Talleyrand, Napoleon requested Talleyrand not tell anyone about the upcoming battle because he did not want to disturb Empress Joséphine. According to Frederick C. Schneid, the French Emperor's chief worry was how he could explain to Joséphine a French defeat.Battlefield

The battle took place about six miles (ten kilometres) southeast of the city ofBrno

Brno ( , ; ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 403,000 inhabitants, making ...

, between that city and Austerlitz () in what is now the Czech Republic. The northern part of the battlefield was dominated by the 700-foot (210-metre) Santon Hill and the 880-foot (270-meter) Žuráň

Žuráň is a small hill (286 metres) near the village of Podolí in the Czech Republic.

Žuráň is a site of considerable archaeological importance , since it features a tumulus in which lie buried members of the ancient Germanic high ari ...

Hill, both overlooking the vital Olomouc

Olomouc (; ) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 103,000 inhabitants, making it the Statutory city (Czech Republic), sixth largest city in the country. It is the administrative centre of the Olomouc Region.

Located on the Morava (rive ...

/Brno road, which was on an east–west axis. To the west of these two hills was the village of Bellowitz (Bedřichovice), and between them, the Bosenitz (Roketnice) stream went south to link up with the Goldbach (Říčka) stream, the latter flowing by the villages of Kobelnitz (Kobylnice), Sokolnitz (Sokolnice), and Telnitz (Telnice).

The centrepiece of the entire area was the Pratzen (Prace) Heights, a gently sloping hill. An aide noted that Napoleon repeatedly told his marshals, "Gentlemen, examine this ground carefully, it is going to be a battlefield; you will have a part to play upon it."

Allied plans and dispositions

The Allied council met on 1 December to discuss proposals for the battle. Most Allied strategists had two fundamental ideas: contacting the enemy and securing the southern flank that held the communication line to Vienna. Although the Tsar and his immediate entourage pushed hard for a battle, Emperor Francis of Austria was more cautious, and, as mentioned, he was seconded by Kutuzov, the Commander-in-chief of the Russians and the Allied troops. The pressure to fight from the Russian nobles and the Austrian commanders, however, was too strong, and the Allies adopted the plan of the Austrian Chief-of-Staff, Franz von Weyrother. This called for a main drive against the French right flank, which the Allies noticed was lightly guarded, and diversionary attacks against the French left. The Allies deployed most of their troops into four columns that would attack the French right. TheRussian Imperial Guard

The Russian Imperial Guard, officially known as the Leib Guard ( ''Leyb-gvardiya'', from German ''Leib'' "body"; cf. Life Guards / Bodyguard), were combined Imperial Russian Army forces units serving as counterintelligence for preventing sabot ...

was held in reserve while Russian troops under Bagration guarded the Allied right. The Russian Tsar stripped Kutuzov of his authority as Commander-in-Chief and gave it to Franz von Weyrother. In the battle, Kutuzov could only command the IV Corps of the Allied army, although he was still the nominal commander because the Tsar was afraid to take over if his favoured plan failed.

French plans and dispositions

Napoleon hoped that the Allied forces would attack, and to encourage them, he deliberately weakened his right flank. On 28 November, Napoleon met with his marshals at Imperial Headquarters, who informed him of their qualms about the forthcoming battle. He shrugged off their suggestion of retreat.

Napoleon's plan envisaged that the Allies would throw many troops to envelop his right flank to cut the French communication line from

Napoleon hoped that the Allied forces would attack, and to encourage them, he deliberately weakened his right flank. On 28 November, Napoleon met with his marshals at Imperial Headquarters, who informed him of their qualms about the forthcoming battle. He shrugged off their suggestion of retreat.

Napoleon's plan envisaged that the Allies would throw many troops to envelop his right flank to cut the French communication line from Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

. As a result, the Allies' center and left flank would be exposed and become vulnerable. To encourage them to do so, Napoleon abandoned the strategic position on the Pratzen Heights, faking the weakness of his forces and his caution. Meanwhile, Napoleon's main force was to be concealed in a dead ground opposite the Heights. According to the plan, the French troops would attack and recapture the Pratzen Heights, then from the Heights, they would launch a decisive assault to the center of the Allied army, cripple them, and encircle them from the rear.

The massive thrust through the Allied centre was conducted by 16,000 troops of Soult's IV Corps. IV Corps' position was cloaked by dense mist during the early stage of the battle; in fact, how long the mist lasted was vital to Napoleon's plan: Soult's troops would become uncovered if the mist dissipated too soon, but if it lingered too long, Napoleon would be unable to determine when the Allied troops had evacuated Pratzen Heights, preventing him from timing his attack properly.

Meanwhile, to support his weak right flank, Napoleon ordered Davout's III Corps to force march from Vienna and join General Legrand's men, who held the extreme southern flank that would bear the heaviest part of the Allied attack. Davout's soldiers had 48 hours to march . Their arrival was crucial in determining the success of the French plan. Indeed, the arrangement of Napoleon on the right flank was precarious as the French had only minimal troops garrisoning there. However, Napoleon was able to use such a risky plan because Davout—the commander of III Corps—was one of Napoleon's best marshals, because the right flank's position was protected by a complicated system of streams and lakes, and because the French had already settled upon a secondary line of retreat through Brunn. The Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the emperor and/or empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial force ...

and Bernadotte's I Corps were held in reserve while the V Corps under Lannes guarded the northern sector of the battlefield, where the new communication line was located.

By 1 December 1805, the French troops had been shifted in accordance with the Allied movement southward, as Napoleon expected.

Battle begins

The battle began at about 8 a.m., with the first allied lines attacking the village of Telnitz, which the 3rd Line Regiment defended. This battlefield sector witnessed heavy fighting in this early action as several ferocious Allied charges evicted the French from the town and forced them onto the other side of the Goldbach. The first men of Davout's corps arrived at this time and threw the Allies out of Telnitz before they, too, were attacked byhussar

A hussar, ; ; ; ; . was a member of a class of light cavalry, originally from the Kingdom of Hungary during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely adopted by light cavalry ...

s and re-abandoned the town. Additional Allied attacks out of Telnitz were checked by French artillery.

Allied columns started pouring against the French right, but not at the desired speed, so the French successfully curbed the attacks. The Allied deployments were mistaken and poorly timed: cavalry detachments under Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (, ; ; ), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein ( ), is a Landlocked country#Doubly landlocked, doubly landlocked Swiss Standard German, German-speaking microstate in the Central European Alps, between Austria in the east ...

on the Allied left flank had to be placed in the right flank, and in the process, they ran into, and slowed down, part of the second column of infantry that was advancing towards the French right. At the time, the planners thought this slowing was disastrous, but later on, it helped the Allies. Meanwhile, the leading elements of the second column were attacking the village of Sokolnitz, which was defended by the 26th Light Regiment and the Tirailleur

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French c ...

s, French skirmisher

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They may be deployed in a skirmish line, an irre ...

s. Initial Allied assaults proved unsuccessful, and General Langeron ordered the bombardment of the village. This deadly barrage forced the French out, and at about the same time, the third column attacked the castle of Sokolnitz. The French, however, counterattacked and regained the village, only to be thrown out again. Conflict in this area ended temporarily when Friant's division (part of III Corps) retook the village. Sokolnitz was perhaps the most contested area on the battlefield and would change hands several times as the day progressed.

While the Allied troops attacked the French right flank, Kutuzov's IV Corps stopped at the Pratzen Heights and stayed still. Just like Napoleon, Kutuzov realized the importance of Pratzen and decided to protect the position. But the young Tsar did not, so he ordered the IV Corps to withdraw from the Heights. This act quickly pushed the Allied army into its grave.

"One sharp blow and the war is over"

At about 8:45 a.m., satisfied at the weakness in the enemy center, Napoleon asked Soult how long it would take for his men to reach the Pratzen Heights, to which the Marshal replied, "Less than twenty minutes, sire." About 15 minutes later, Napoleon ordered the attack, adding, "One sharp blow and the war is over." A dense fog helped to cloud the advance of St. Hilaire's French division, but as they ascended the slope, the legendary 'Sun of Austerlitz' ripped the mist apart and encouraged them forward. Russian soldiers and commanders on top of the heights were stunned to see so many French troops coming towards them. Allied commanders moved some of the delayed detachments of the fourth column into this bitter struggle. Over an hour of fighting destroyed much of this unit. The other men from the second column, primarily inexperienced Austrians, also participated in the struggle and swung the numbers against one of the best fighting forces in the French army, eventually forcing them to withdraw down the slopes. However, gripped by desperation, St. Hilaire's men struck hard again and bayoneted the Allies out of the heights. To the north, General Vandamme's division attacked an area called Staré Vinohrady ("Old Vineyards") and, through talented skirmishing and deadly volleys, broke several Allied battalions. The battle had firmly turned in France's favor, but it was far from over. Napoleon ordered Bernadotte's I Corps to support Vandamme's left and moved his command center from Žuráň Hill to St. Anthony's Chapel on the Pratzen Heights. The problematic position of the Allies was confirmed by the decision to send in theRussian Imperial Guard

The Russian Imperial Guard, officially known as the Leib Guard ( ''Leyb-gvardiya'', from German ''Leib'' "body"; cf. Life Guards / Bodyguard), were combined Imperial Russian Army forces units serving as counterintelligence for preventing sabot ...

; Grand Duke Constantine, Tsar Alexander's brother, commanded the Guard and counterattacked in Vandamme's section of the field, forcing a bloody effort and the only loss of a French standard in the battle (a battalion of the 4th Line Regiment was defeated). Sensing trouble, Napoleon ordered his own heavy Guard cavalry forward. These men pulverized their Russian counterparts, but with both sides pouring in large masses of cavalry, no victory was clear.

The Russians had a numerical advantage; however, the tide soon swung as Drouet's Division, the 2nd of Bernadotte's I Corps, deployed on the flank of the action and allowed French cavalry to seek refuge behind their lines. The horse artillery

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving, and fast-firing field artillery that consisted of light cannons or howitzers attached to light but sturdy two-wheeled carriages called caissons or limbers, with the individual crewmen riding on h ...

of the Guard also inflicted heavy casualties on the Russian cavalry and fusiliers. The Russians broke, and many died as they were pursued by the reinvigorated French cavalry for about a quarter of a mile. Kutuzov was severely wounded, and his son-in-law, Ferdinand von Tiesenhausen, was killed.Lê Vinh Quốc, Nguyễn Thị Thư, Lê Phụng Hoàng, pp. 154–160

Endgame

Meanwhile, the northernmost part of the battlefield also witnessed heavy fighting. The Prince of Liechtenstein's heavy cavalry began to assault Kellermann's lighter cavalry forces after eventually arriving at the correct position in the field. The fighting initially went well for the French, but Kellerman's forces took cover behind General Caffarelli's infantry division once it became clear that Russian numbers were too great. Caffarelli's men halted the Russian assaults and permittedMurat

Murat may refer to:

Places Australia

* Murat Bay, a bay in South Australia

* Murat Marine Park, a marine protected area

France

* Murat, Allier, a commune in the department of Allier

* Murat, Cantal, a commune in the department of Cantal

Elsew ...

to send two cuirassier divisions (one commanded by d'Hautpoul and the other one by Nansouty) into the fray to finish off the Russian cavalry for good. The ensuing mêlée was bitter and long, but the French ultimately prevailed. Lannes then led his V Corps against Bagration's men and, after hard fighting, drove the skilled Russian commander off the field. He wanted to pursue, but Murat, who was in control of this sector on the battlefield, was against the idea.

Napoleon's focus shifted towards the southern end of the battlefield, where the French and the Allies were still fighting over Sokolnitz and Telnitz. In an effective double-pronged assault, St. Hilaire's division and part of Davout's III Corps smashed through the enemy at Sokolnitz, which persuaded the commanders of the first two columns, Generals Kienmayer and Langeron

Langeron is a commune in the Nièvre department in central France.

Demographics

On 1 January 2019, the estimated population was 357.

See also

*Communes of the Nièvre department

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community ...

, to flee as fast as they could. Buxhowden, the commander of the Allied left and the man responsible for leading the attack, was completely drunk and fled as well. Kienmayer covered his withdrawal with the O'Reilly

O'Reilly () is a common Irish surname. The O'Reillys were historically the kings of East Bréifne in what is today County Cavan. The clan were part of the Connachta's Uí Briúin Bréifne kindred and were closely related to the Ó Ruairc ( ...

light cavalry, who managed to defeat five of six French cavalry regiments before they had to retreat.

General panic seized the Allied army, and it abandoned the field in all possible directions. A famousalbeit disputed

episode occurred during this retreat: defeated Russian forces withdrew south towards Vienna via the frozen Satschan ponds. French artillery pounded towards the men, and the ice was broken by the bombardment. The fleeing men drowned in the cold ponds, dozens of Russian artillery pieces going down with them. Estimates of how many guns were captured differ: there may have been as few as 38 or more than 100. Sources also differ about casualties, with figures ranging between 200 and 2,000 dead. Many drowning Russians were saved by their victorious foes. However, local evidence later made public suggests that Napoleon's account of the catastrophe may have been exaggerated; on his instructions, the lakes were drained a few days after the battle and the corpses of only two or three men, with some 150 horses, were found. On the other hand, Tsar Alexander I attested to the incident after the wars.

Military and political results

Allied casualties stood at about 36,000 out of an army of 89,000, representing about 38% of their effective forces. The French were not unscathed in the battle, losing around 9,000 out of an army of 66,000, or about 13% of their forces. The Allies also lost some 180 guns and about 50 standards. The victory was met by sheer amazement and delirium in Paris, where the nation had been teetering on the brink of financial collapse just days earlier. Napoleon wrote to Josephine, "I have beaten the Austro-Russian army commanded by the two emperors. I am a little weary. ... I embrace you." Napoleon's comments in this letter led to the battle's other famous designation, "Battle of the Three Emperors". However, Napoleon was mistaken as Emperor Francis of Austria was not present on the battlefield. Tsar Alexander perhaps best summed up the harsh times for the Allies by stating, "We are babies in the hands of a giant." After hearing the news of Austerlitz, Pitt said of a map of Europe, "Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years." France and Austria signed a truce on 4 December, and the Treaty of Pressburg 22 days later took the latter out of the war. Austria agreed to recognize French territory captured by the treaties of Campo Formio (1797) and Lunéville (1801), cede land to Bavaria,Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

and Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

, which were Napoleon's German allies, pay 40 million francs in war indemnities and cede Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

to the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. It was a harsh end for Austria but certainly not a catastrophic peace. The Russian army was allowed to withdraw to home territory, and the French ensconced themselves in Southern Germany. The Holy Roman Empire was extinguished, 1806 being seen as its final year. Napoleon created the Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine or Rhine Confederation, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austrian Empire, Austria ...

, a string of German states meant to serve as a buffer between France and Prussia. Prussia saw these and other moves as an affront to its status as the main power of Central Europe, and it went to war with France in 1806.

Rewards

Napoleon's words to his troops after the battle were full of praise: ''Soldats! Je suis content de vous'' (). Napoleon wrote to his victorious army on the night of Austerlitz with his customaryrhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

:

"''Even at this hour, before this great day shall pass and be lost in the ocean of eternity, your emperor just address you, and say how satisfied he is with the conduct of all those who had the good fortune to fight in this memorable battle. Soldiers! You are the finest warriors in the World. The recollection of this day, and of your deeds, will be eternal! Thousands of ages hereafter, as long as the events of the universe continue to be relate, will it be told that a Russian army of 76,000 men, hired by the gold of England, was annihilated by you on the plains of Olmütz.''"''Napoleon's Proclamation following Austerlitz''. Dated 3 December 1805. Translated by Markham, J. David.

The Emperor provided two million golden francs to the higher officers and 200 francs to each soldier, with large pensions for the widows of the fallen, also providing 6,000 Francs for the widows of fallen generals. Orphaned children were adopted by Napoleon personally and were allowed to add "Napoleon" to their baptismal and family names. He could afford this, and much else besides, thanks to the return of financial confidence that swept the country as government bonds leaped from 45% to 66% of their face value on the news of victory.

This battle is one of four for which Napoleon never awarded a victory title

A victory title is an honorific title adopted by a successful military commander to commemorate his defeat of an enemy nation. The practice is first known in Ancient Rome and is still most commonly associated with the Romans, but it was also adop ...

, the others being Marengo, Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, and Friedland.

In popular culture

Artists and musicians on the side of France and her conquests expressed their sentiments in the popular and elite art of the time. Prussian music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann, in his famous review of Beethoven's 5th Symphony,

Artists and musicians on the side of France and her conquests expressed their sentiments in the popular and elite art of the time. Prussian music critic E. T. A. Hoffmann, in his famous review of Beethoven's 5th Symphony,

singles out for special abuse a certain ''Bataille des trois Empereurs'', a French battle symphony by Louis Jadin celebrating Napoleon's victory at Austerlitz.

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

dramatized the battle as the conclusion of Book 3 and Volume 1 of ''War and Peace

''War and Peace'' (; pre-reform Russian: ; ) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. Set during the Napoleonic Wars, the work comprises both a fictional narrative and chapters in which Tolstoy discusses history and philosophy. An ...

'', making it a crucial moment in the lives of both Andrei Bolkonsky, who is badly wounded, and of Nikolai Rostov.

Archibald Alison in his ''History of Europe'' (1836) offers the first recorded telling of the apocryphal story that when the Allies descended the Pratzen Heights to attack Napoleon's supposedly weak flank,

The marshals who surrounded Napoleon saw the advantage, and eagerly besought him to give the signal for action; but he restrained their ardour ... "when the enemy is making a false movement we must take good care not to interrupt him."In subsequent accounts, this Napoleonic quote would undergo various changes until it became: "Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake."

Historical views

Napoleon did not succeed in defeating the Allied army as thoroughly as he wanted, but historians and enthusiasts alike recognize that the original plan provided a significant victory, comparable to other great tactical battles such as

Napoleon did not succeed in defeating the Allied army as thoroughly as he wanted, but historians and enthusiasts alike recognize that the original plan provided a significant victory, comparable to other great tactical battles such as Cannae

Cannae (now , ) is an ancient village of the region of south east Italy. It is a (civil parish) of the (municipality) of . Cannae was formerly a bishopric, and is a Latin Catholic titular see (as of 2022).

Geography

The commune of Cannae i ...

. Some historians suggest that Napoleon was so successful at Austerlitz that he lost touch with reality, and what used to be French foreign policy became a "personal Napoleonic one" after the battle. In French history

The first written records for the history of France appeared in the Iron Age.

What is now France made up the bulk of the region known to the Romans as Gaul. Greek writers noted the presence of three main ethno-linguistic groups in the area: t ...

, Austerlitz is acknowledged as an impressive military victory, and in the 19th century, when fascination with the First French Empire

The First French Empire or French Empire (; ), also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. It lasted from ...

was at its height, the battle was revered by French authors such as Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, who wrote of the "sound of heavy cannons rolling towards Austerlitz" echoing in the "depths of isthoughts". In the 2005 bicentennial, however, controversy erupted when neither French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

nor Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin

Dominique Marie François René Galouzeau de Villepin (; born 14 November 1953) is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 31 May 2005 to 17 May 2007 under President Jacques Chirac.

In his career working at the Ministry ...

attended any functions commemorating the battle. On the other hand, some residents of France's overseas departments protested against what they viewed as the "official commemoration of Napoleon", arguing that Austerlitz should not be celebrated since they believed that Napoleon committed genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

against colonial people.

After the battle, Tsar Alexander I blamed Kutuzov, the Commander-in-chief of the Allied Army. However, it is clear that Kutuzov planned to retreat farther to the rear, where the Allied Army had a sharp advantage in logistics. Had the Allied Army retreated further, they might have been reinforced by Archduke Charles's troops from Italy, and the Prussians might have joined the Coalition against Napoleon. A French army at the end of its supply lines, in a place that had no food supplies, might have faced a very different ending from the one they achieved at the real battle of Austerlitz.

Monuments and protection of the area

municipalities

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

:

* Blažovice

Blažovice is a municipality and village in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 1,200 inhabitants.

Blažovice lies approximately east of Brno and south-east of Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the ...

* Holubice

* Hostěrádky-Rešov

Hostěrádky-Rešov is a municipality and village in Vyškov District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 800 inhabitants.

Hostěrádky-Rešov lies approximately south-west of Vyškov, south-east of Brno, and sou ...

* Jiříkovice

* Kobylnice

* Křenovice

* Podolí

* Ponětovice

Ponětovice is a municipality and village in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 400 inhabitants.

Ponětovice lies approximately south-east of Brno and south-east of Prague

Prague ( ; ) ...

* Prace

* Sivice

* Šlapanice

Šlapanice () is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 8,000 inhabitants.

Administrative division

Šlapanice consists of five municipal parts (in brackets population according to the 2021 ...

* Slavkov u Brna

Slavkov u Brna (; ) is a town in Vyškov District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,300 inhabitants. The town gave its name to the Battle of Austerlitz, which took place several kilometres west of the town. The his ...

* Sokolnice

* Telnice

* Tvarožná

* Újezd u Brna

Újezd u Brna (, ) is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 3,400 inhabitants.

Geography

Újezd u Brna is located about southeast of Brno. It lies in an agricultural landscape of the Dyje ...

* Velatice

* Žatčany

* Zbýšov

Zbýšov is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 3,700 inhabitants.

Geography

Zbýšov is located about west of Brno. It lies on the border between the Křižanov Highlands and Boskov ...

Near Prace is the Cairn of Peace Memorial

The Cairn of Peace Memorial (, 'Mound of Peace') is the memorial to the fallen in the Battle of Austerlitz, the first peace memorial in Europe. It is located by the village of Prace, Czech Republic on the , one of the key points of the battle.

...

, claimed to be the first peace memorial in Europe. It was designed and built in the Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau ( ; ; ), Jugendstil and Sezessionstil in German, is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and ...

style by Josef Fanta in 1910–1912. World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

postponed the monument's dedication until 1923. It is high, square, with four female statues symbolizing France, Austria, Russia and Moravia. Within is a chapel with an ossuary. A nearby small museum commemorates the battle. Every year, the events of the Battle of Austerlitz are commemorated in a ceremony.

Other memorials located in the monument zone include, among others:

* The Staré Vinohrady height near Zbýšov

Zbýšov is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 3,700 inhabitants.

Geography

Zbýšov is located about west of Brno. It lies on the border between the Křižanov Highlands and Boskov ...

saw the bloody collision of the French and Russian guards. In 2005, the Monument to the Three Emperors has been erected here.

* ''Stará Pošta'' ("Old Post") in Kovalovice is an original building from 1785, which now serves as a hotel and restaurant. On 28 November 1805, the French cavalry general Murat set up his headquarters here. On the day of the battle, the Russian general Bagration had his headquarters here. After the battle, Napoleon slept in this house and held preliminary negotiations about an armistice. A small museum commemorates these events.

* On in Tvarožná is a small white chapel. The hill was a mainstay of the French position and allowed the French artillery to dominate the northern portion of the battlefield. Below the hill, the yearly historical reenactment

Historical reenactment (or re-enactment) is an educational entertainment, educational or entertainment activity in which mainly amateur hobbyists and history enthusiasts dress in historical uniforms and follow a plan to recreate aspects of a histor ...

s take place.

* On Žuráň

Žuráň is a small hill (286 metres) near the village of Podolí in the Czech Republic.

Žuráň is a site of considerable archaeological importance , since it features a tumulus in which lie buried members of the ancient Germanic high ari ...

Hill, where Napoleon was headquartered, a granite monument depicts the battlefield positions.

* Slavkov Castle, where an armistice was signed between Austria and France after the battle on 6 December 1805. There is a small historical museum and a multimedia presentation about the battle.

Several monuments to the battle can be found far beyond the battle area. A notable monument is the Pyramid of Austerlitz

The Pyramid of Austerlitz is a 36-metre-high pyramid of earth, built in 1804 by Napoleon's soldiers on one of the highest points of the Utrecht Hill Ridge, in the municipality of Woudenberg, Woudenberg, the Netherlands. Atop the pyramid is a ston ...

, built by French soldiers stationed there to commemorate the 1805 campaign near Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

in the Netherlands. In Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, the 44-metre-high bronze Colonne Vendôme, a celebration of Napoleon, also stands on the Place Vendôme

The Place Vendôme (), earlier known as the Place Louis-le-Grand, and also as the Place Internationale, is a square in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France, located to the north of the Tuileries Gardens and east of the Église de la Madelein ...

. The monument was initially called the Column of Austerlitz and, according to propaganda, was cast from the melted-down barrels of Allied guns from the Battle of Austerlitz. Several other sites and public buildings commemorate the encounter in Paris, such as Pont d'Austerlitz

The Pont d'Austerlitz is a bridge which crosses the Seine River in Paris, France. It owes its name to the battle of Austerlitz (1805).

Location

The bridge links the 12th arrondissement at the rue Ledru-Rollin, to the 5th and 13th arrondissements, ...

and nearby Gare d'Austerlitz. A scene from the battle is also depicted on the bas-relief of the eastern pillar of the Arc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, often called simply the Arc de Triomphe, is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Plac ...

and Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel

The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel () () is a triumphal arch in Paris, located in the Place du Carrousel. It is an example of Neoclassical architecture, Neoclassical architecture in the Corinthian order. It was built between 1806 and 1808 to commemo ...

.

See also

* Gare d'Austerlitz *Military career of Napoleon

The military career of Napoleon spanned over 20 years. He led French armies in the French Revolutionary Wars and later, as Emperor of the French, emperor, in the Napoleonic Wars. Despite his rich war-winning record, Napoleon's military career end ...

Explanatory notes

Citations

General references

* * * * * * * * * * Dupuy, Trevor N. (1990). ''Understanding Defeat: How to Recover from Loss in Battle to Gain Victory in War''. Paragon House. . * Farwell, Byron (2001). ''The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View''. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. . * * * * Goetz, Robert. ''1805: Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition'' (Greenhill Books, 2005). . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Marbot, Jean-Baptiste Antoine Marcelin. "The Battle of Austerlitz", ''Napoleon: Symbol for an Age, A Brief History with Documents'', ed. Rafe Blaufarb (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2008), 122–123. * * * * * * * * Tolstoy, Leo. ''War and Peace''. London: Penguin Group, 1982. * * *External links

*Austerlitz order of battle

*

*

Austerlitz 2005: la bataille des trois empereurs

*

''Austerlitz Online Game''

(Pousse-pion éditions, 2010) * (Napoleonic Miniatures Wargame Society of Toronto) * *

View on battle place – virtual show

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Austerlitz 1805 Battles commanded by Napoleon 1805 in France 1805 in the Austrian Empire Conflicts in 1805 Battles in Moravia Battles of the War of the Third Coalition involving Austria Battles of the War of the Third Coalition involving Russia Battles involving the Kingdom of Italy (Napoleonic) Czech lands under Habsburg rule December 1805 Vyškov District Battles inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe History of the South Moravian Region Joachim Murat Battles of the Napoleonic Wars involving Liechtenstein