polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

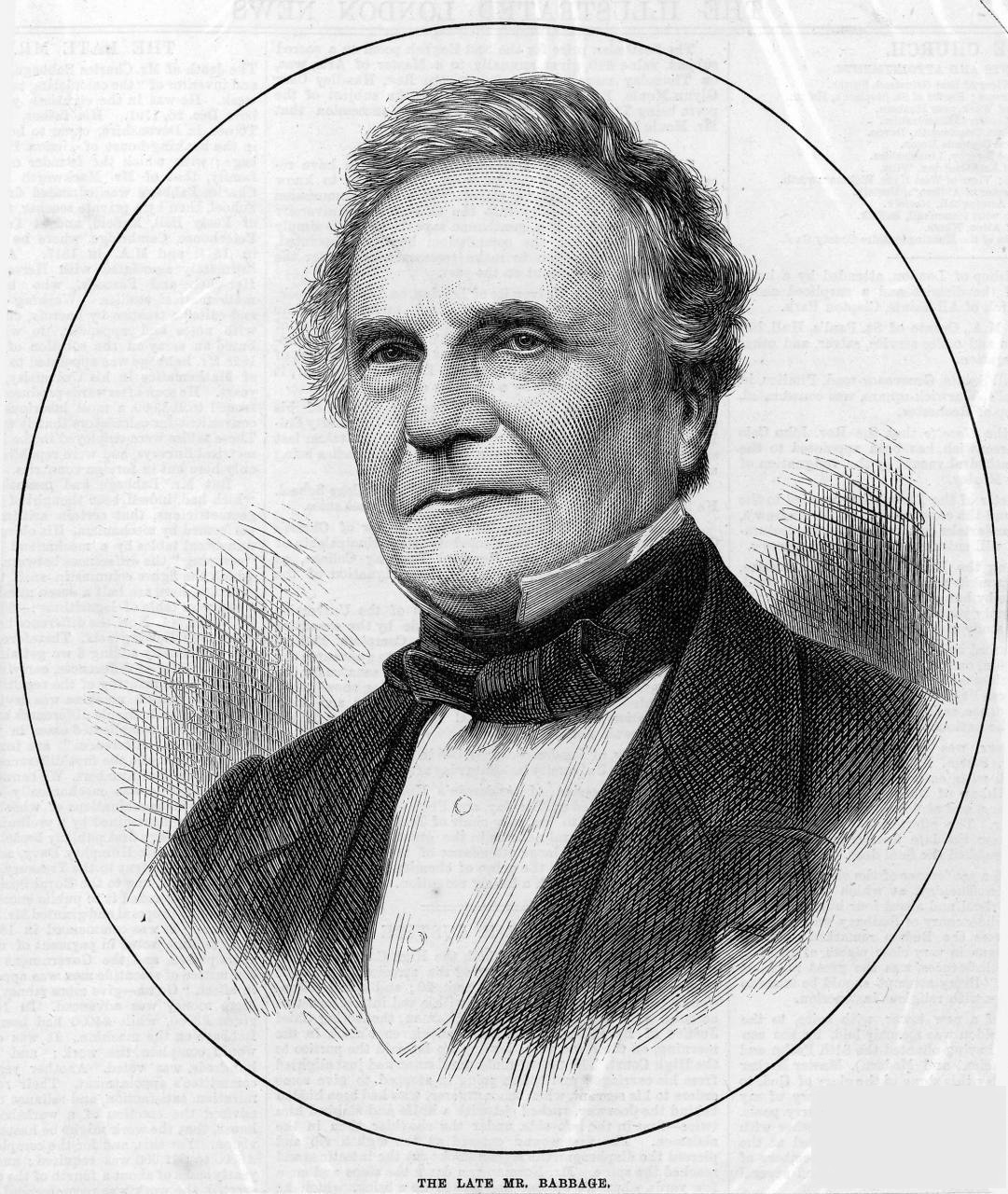

. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered by some to be " father of the computer". He is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer

A mechanical computer is a computer built from mechanical components such as levers and gears rather than electronic components. The most common examples are adding machines and mechanical counters, which use the turning of gears to incremen ...

, the difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was created by Charles Babbage. The name ''difference engine'' is derived from the method of finite differen ...

, that eventually led to more complex electronic designs, though all the essential ideas of modern computers are to be found in his analytical engine, programmed using a principle openly borrowed from the Jacquard loom

The Jacquard machine () is a device fitted to a loom that simplifies the process of manufacturing textiles with such complex patterns as brocade, damask and matelassé. The resulting ensemble of the loom and Jacquard machine is then called a Jac ...

. As part of his computer work, he also designed the first computer printers. He had a broad range of interests in addition to his work on computers covered in his 1832 book ''Economy of Manufactures and Machinery''. He was an important figure in the social scene in London, and is credited with importing the "scientific soirée" from France with his well-attended Saturday evening soirées. His varied work in other fields has led him to be described as "pre-eminent" among the many polymaths of his century.

Babbage, who died before the complete successful engineering of many of his designs, including his Difference Engine and Analytical Engine, remained a prominent figure in the ideating of computing. Parts of his incomplete mechanisms are on display in the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

in London. In 1991, a functioning difference engine was constructed from the original plans. Built to tolerances achievable in the 19th century, the success of the finished engine indicated that Babbage's machine would have worked.

Early life

Babbage's birthplace is disputed, but according to the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'' he was most likely born at 44 Crosby Row, Walworth Road

The A215 is an A roads in Great Britain, A road in south London, starting at Elephant and Castle and finishing around Shirley, London, Shirley. It runs through the London Boroughs of London Borough of Lambeth, Lambeth, London Borough of Southw ...

, London, England. A blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving a ...

on the junction of Larcom Street and Walworth Road commemorates the event.

His date of birth was given in his obituary in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' as 26 December 1792; but then a nephew wrote to say that Babbage was born one year earlier, in 1791. The parish register of St. Mary's, Newington, London, shows that Babbage was baptised

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

on 6 January 1792, supporting a birth year of 1791.

Babbage was one of four children of Benjamin Babbage and Betsy Plumleigh Teape. His father was a banking partner of

Babbage was one of four children of Benjamin Babbage and Betsy Plumleigh Teape. His father was a banking partner of William Praed

William Praed (24 June 1747 – 9 October 1833) was an English businessman, banker, and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1774 to 1808.

He is not to be confused with his first cousin of the same name, William Mackworth Praed, serj ...

in founding Praed's & Co. of Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a street in Central London, England. It runs west to east from Temple Bar, London, Temple Bar at the boundary of the City of London, Cities of London and City of Westminster, Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the Lo ...

, London, in 1801. In 1808, the Babbage family moved into the old Rowdens house in East Teignmouth. Around the age of eight, Babbage was sent to a country school in Alphington near Exeter to recover from a life-threatening fever. For a short time, he attended King Edward VI Grammar School in Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and ab ...

, South Devon, but his health forced him back to private tutors for a time.

Babbage then joined the 30-student Holmwood Academy, in Baker Street, Enfield, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

, under the Reverend Stephen Freeman. The academy had a library that prompted Babbage's love of mathematics. He studied with two more private tutors after leaving the academy. The first was a clergyman near Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

; through him Babbage encountered Charles Simeon

Charles Simeon (24 September 1759 – 13 November 1836) was an English Evangelical Anglicanism, evangelical Anglican cleric and biblical commentator who led the evangelical 'Low Church' movement, in reaction to the liturgically and episcopally ...

and his evangelical followers, but the tuition was not what he needed. He was brought home, to study at the Totnes school: this was at age 16 or 17. The second was an Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

tutor, under whom Babbage reached a level in Classics sufficient to be accepted by the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

.

At the University of Cambridge

Babbage arrived atTrinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, in October 1810. He was already self-taught in some parts of contemporary mathematics; he had read Robert Woodhouse, Joseph Louis Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi LagrangiaMaria Gaetana Agnesi

Maria Gaetana Agnesi (16 May 1718 – 9 January 1799) was an Italians, Italian mathematician, philosopher, Theology, theologian, and humanitarianism, humanitarian. She was the first woman to write a mathematics handbook and the list of women in ...

. As a result, he was disappointed in the standard mathematical instruction available at the university.

Babbage, John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

, George Peacock, and several other friends formed the Analytical Society in 1812; they were also close to Edward Ryan.Wilkes (2002) ''p.''355 As a student, Babbage was also a member of other societies such as The Ghost Club, concerned with investigating supernatural phenomena, and the Extractors Club, dedicated to liberating its members from the madhouse, should any be committed to one.

In 1812, Babbage transferred to Peterhouse, Cambridge

Peterhouse is the oldest Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Peterhouse has around 300 undergraduate and 175 graduate stud ...

. He was the top mathematician there, but did not graduate with honours. He instead received a degree without examination in 1814. He had defended a thesis that was considered blasphemous in the preliminary public disputation, but it is not known whether this fact is related to his not sitting the examination.

After Cambridge

Considering his reputation, Babbage quickly made progress. He lectured to theRoyal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

on astronomy in 1815, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1816. After graduation, on the other hand, he applied for positions unsuccessfully, and had little in the way of a career. In 1816 he was a candidate for a teaching job at Haileybury College; he had recommendations from James Ivory and John Playfair, but lost out to Henry Walter. In 1819, Babbage and Herschel visited Paris and the Society of Arcueil The Society of Arcueil was a circle of French scientists who met regularly on summer weekends between 1806 and 1822 at the country houses of Claude Louis Berthollet and Pierre Simon Laplace at Arcueil, then a village 3 miles south of Paris.

Members ...

, meeting leading French mathematicians and physicists. That year Babbage applied to be professor at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

, with the recommendation of Pierre Simon Laplace; the post went to William Wallace.

With Herschel, Babbage worked on the electrodynamics

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

of Arago's rotations, publishing in 1825. Their explanations were only transitional, being picked up and broadened by Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

. The phenomena

A phenomenon ( phenomena), sometimes spelled phaenomenon, is an observable Event (philosophy), event. The term came into its modern Philosophy, philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be ...

are now part of the theory of eddy currents, and Babbage and Herschel missed some of the clues to unification of electromagnetic theory

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interact ...

, staying close to Ampère's force law

In magnetostatics, Ampère's force law describes the force of attraction or repulsion between two current-carrying wires. The physical origin of this force is that each wire generates a magnetic field, following the Biot–Savart law, and th ...

.

Babbage purchased the actuarial tables of George Barrett, who died in 1821 leaving unpublished work, and surveyed the field in 1826 in ''Comparative View of the Various Institutions for the Assurance of Lives''. This interest followed a project to set up an insurance company, prompted by Francis Baily and mooted in 1824, but not carried out. Babbage did calculate actuarial tables for that scheme, using Equitable Society

The Equitable Life Assurance Society (Equitable Life), founded in 1762, is a life insurance company in the United Kingdom. The world's oldest mutual insurer, it pioneered age-based premiums based on mortality rate, laying "the framework for sci ...

mortality data from 1762 onwards.

During this whole period, Babbage depended awkwardly on his father's support, given his father's attitude to his early marriage, of 1814: he and Edward Ryan wedded the Whitmore sisters. He made a home in Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also ) is an area in London, England, and is located in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. Oxford Street forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropo ...

in London and established a large family. On his father's death in 1827, Babbage inherited a large estate (value around £100,000, equivalent to £ or $ today), making him independently wealthy. After his wife's death in the same year he spent time travelling. In Italy he met Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, foreshadowing a later visit to Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

. In April 1828 he was in Rome, and relying on Herschel to manage the difference engine project, when he heard that he had become a professor at Cambridge, a position he had three times failed to obtain (in 1820, 1823 and 1826).

Royal Astronomical Society

Babbage was instrumental in founding theRoyal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) is a learned society and charitable organisation, charity that encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, planetary science, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. Its ...

in 1820, initially known as the Astronomical Society of London. Its original aims were to reduce astronomical calculations to a more standard form, and to circulate data. These directions were closely connected with Babbage's ideas on computation, and in 1824 he won its Gold Medal

A gold medal is a medal awarded for highest achievement in a non-military field. Its name derives from the use of at least a fraction of gold in form of plating or alloying in its manufacture.

Since the eighteenth century, gold medals have b ...

, cited "for his invention of an engine for calculating mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and astronomical tables".

Babbage's motivation to overcome errors in tables by mechanisation had been a commonplace since Dionysius Lardner

Dionysius Lardner FRS FRSE (3 April 179329 April 1859) was an Irish scientific writer who popularised science and technology, and edited the 133-volume '' Cabinet Cyclopædia''.

Early life in Dublin

He was born in Dublin on 3 April 1793 th ...

wrote about it in 1834 in the ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' (under Babbage's guidance). The context of these developments is still debated. Babbage's own account of the origin of the difference engine begins with the Astronomical Society's wish to improve ''The Nautical Almanac

''The Nautical Almanac'' has been the familiar name for a series of official British almanacs published under various titles since the first issue of ''The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris'', for 1767: this was the first nautical alm ...

''. Babbage and Herschel were asked to oversee a trial project, to recalculate some part of those tables. With the results to hand, discrepancies were found. This was in 1821 or 1822, and was the occasion on which Babbage formulated his idea for mechanical computation. The issue of the ''Nautical Almanac'' is now described as a legacy of a polarisation in British science caused by attitudes to Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James Co ...

, who had died in 1820.

Babbage studied the requirements to establish a modern

Babbage studied the requirements to establish a modern postal system

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal sy ...

, with his friend Thomas Frederick Colby, concluding there should be a uniform rate that was put into effect with the introduction of the Uniform Fourpenny Post supplanted by the Uniform Penny Post

The Uniform Penny Post was a component of the comprehensive reform of the Royal Mail, the UK's official postal service, that took place in the 19th century. The reforms were a government initiative to eradicate the abuse and corruption of the e ...

in 1839 and 1840. Colby was another of the founding group of the Society. He was also in charge of the Survey of Ireland

Ordnance Survey Ireland (OSI; ) was the national mapping agency of the Republic of Ireland. It was established on 4 March 2002 as a body corporate. It was the successor to the former Ordnance Survey of Ireland. It and the Ordnance Survey of N ...

. Herschel and Babbage were present at a celebrated operation of that survey, the remeasuring of the Lough Foyle

Lough Foyle, sometimes Loch Foyle ( or "loch of the lip"), is the estuary of the River Foyle, on the north coast of Ireland. It lies between County Londonderry in Northern Ireland and County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland. Sovereignty over t ...

baseline.

British Lagrangian School

The Analytical Society had initially been no more than an undergraduate provocation. During this period it had some more substantial achievements. In 1816, Babbage, Herschel and Peacock published a translation from French of the lectures ofSylvestre Lacroix Sylvestre can refer to:

People Surname

Given name

Middle name

* Carlos Sylvestre Begnis (1903–1980), Argentine medical doctor and politician

* Philippe Sylvestre Dufour (1622–1687), French Protestant apothecary, banker, collector, an ...

, which was then the state-of-the-art calculus textbook.

Reference to Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi Lagrangiaformal power series

In mathematics, a formal series is an infinite sum that is considered independently from any notion of convergence, and can be manipulated with the usual algebraic operations on series (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, partial su ...

. British mathematicians had used them from about 1730 to 1760. As re-introduced, they were not simply applied as notations in differential calculus

In mathematics, differential calculus is a subfield of calculus that studies the rates at which quantities change. It is one of the two traditional divisions of calculus, the other being integral calculus—the study of the area beneath a curve. ...

. They opened up the fields of functional equation

In mathematics, a functional equation

is, in the broadest meaning, an equation in which one or several functions appear as unknowns. So, differential equations and integral equations are functional equations. However, a more restricted meaning ...

s (including the difference equation

In mathematics, a recurrence relation is an equation according to which the nth term of a sequence of numbers is equal to some combination of the previous terms. Often, only k previous terms of the sequence appear in the equation, for a parameter ...

s fundamental to the difference engine) and operator (D-module

In mathematics, a ''D''-module is a module (mathematics), module over a ring (mathematics), ring ''D'' of differential operators. The major interest of such ''D''-modules is as an approach to the theory of linear partial differential equations. S ...

) methods for differential equations. The analogy of difference and differential equations was notationally changing Δ to D, as a "finite" difference becomes "infinitesimal". These symbolic directions became popular, as operational calculus

Operational calculus, also known as operational analysis, is a technique by which problems in Mathematical Analysis, analysis, in particular differential equations, are transformed into algebraic problems, usually the problem of solving a polynomia ...

, and pushed to the point of diminishing returns. The Cauchy concept of limit was kept at bay. Woodhouse had already founded this second "British Lagrangian School" with its treatment of Taylor series

In mathematics, the Taylor series or Taylor expansion of a function is an infinite sum of terms that are expressed in terms of the function's derivatives at a single point. For most common functions, the function and the sum of its Taylor ser ...

as formal.

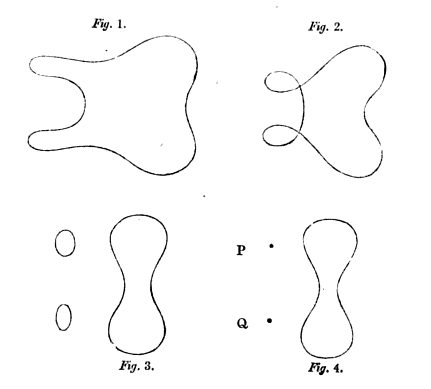

In this context function composition

In mathematics, the composition operator \circ takes two function (mathematics), functions, f and g, and returns a new function h(x) := (g \circ f) (x) = g(f(x)). Thus, the function is function application, applied after applying to . (g \c ...

is complicated to express, because the chain rule

In calculus, the chain rule is a formula that expresses the derivative of the Function composition, composition of two differentiable functions and in terms of the derivatives of and . More precisely, if h=f\circ g is the function such that h ...

is not simply applied to second and higher derivatives. This matter was known to Woodhouse by 1803, who took from Louis François Antoine Arbogast

Louis François Antoine Arbogast (4 October 1759 – 8 April 1803) was a French mathematician. He was born at Mutzig in Alsace and died at Strasbourg, where he was professor. He wrote on Series (mathematics), series and the Calculus, derivatives ...

what is now called Faà di Bruno's formula

Faà di Bruno's formula is an identity in mathematics generalizing the chain rule to higher derivatives. It is named after , although he was not the first to state or prove the formula. In 1800, more than 50 years before Faà di Bruno, the French ...

. In essence it was known to Abraham De Moivre

Abraham de Moivre FRS (; 26 May 166727 November 1754) was a French mathematician known for de Moivre's formula, a formula that links complex numbers and trigonometry, and for his work on the normal distribution and probability theory.

He move ...

(1697). Herschel found the method impressive, Babbage knew of it, and it was later noted by Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (''née'' Byron; 10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852), also known as Ada Lovelace, was an English mathematician and writer chiefly known for her work on Charles Babbage's proposed mechanical general-pur ...

as compatible with the analytical engine. In the period to 1820 Babbage worked intensively on functional equations in general, and resisted both conventional finite difference

A finite difference is a mathematical expression of the form . Finite differences (or the associated difference quotients) are often used as approximations of derivatives, such as in numerical differentiation.

The difference operator, commonly d ...

s and Arbogast's approach (in which Δ and D were related by the simple additive case of the exponential map). But via Herschel he was influenced by Arbogast's ideas in the matter of iteration

Iteration is the repetition of a process in order to generate a (possibly unbounded) sequence of outcomes. Each repetition of the process is a single iteration, and the outcome of each iteration is then the starting point of the next iteration.

...

, i.e. composing a function with itself, possibly many times. Writing in a major paper on functional equations in the ''Philosophical Transactions

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the second journ ...

'' (1815/6), Babbage said his starting point was work of Gaspard Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Péluse (; 9 May 1746 – 28 July 1818) was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry, (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geometry. Dur ...

.

Academic

From 1828 to 1839, Babbage wasLucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas (politician), Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge U ...

at Cambridge. Not a conventional resident don, and inattentive to his teaching responsibilities, he wrote three topical books during this period of his life. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1832. Babbage was out of sympathy with colleagues: George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, as well as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics from 1826 to 1828 and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements inc ...

, his predecessor as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge, thought an issue should be made of his lack of interest in lecturing. Babbage planned to lecture in 1831 on political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

. Babbage's reforming direction looked to see university education more inclusive, universities doing more for research, a broader syllabus and more interest in applications; but William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

found the programme unacceptable. A controversy Babbage had with Richard Jones lasted for six years. He never did give a lecture.

It was during this period that Babbage tried to enter politics. Simon Schaffer

Simon J. Schaffer (born 1 January 1955) is a historian of science, previously a professor of the history and philosophy of science at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge and was editor of '' The B ...

writes that his views of the 1830s included disestablishment of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, a broader political franchise, and inclusion of manufacturers as stakeholders. He twice stood for Parliament as a candidate for the borough of Finsbury

Finsbury is a district of Central London, forming the southeastern part of the London Borough of Islington. It borders the City of London.

The Manorialism, Manor of Finsbury is first recorded as ''Vinisbir'' (1231) and means "manor of a man c ...

. In 1832 he came in third among five candidates, missing out by some 500 votes in the two-member constituency when two other reformist candidates, Thomas Wakley and Christopher Temple, split the vote. In his memoirs Babbage related how this election brought him the friendship of Samuel Rogers: his brother Henry Rogers wished to support Babbage again, but died within days. In 1834 Babbage finished last among four. In 1832, Babbage, Herschel and Ivory were appointed Knights of the Royal Guelphic Order

The Royal Guelphic Order (), sometimes referred to as the Hanoverian Guelphic Order, is a Kingdom of Hanover, Hanoverian order of chivalry instituted on 28 April 1815 by the Prince Regent (later King George IV). It takes its name from the House ...

, however they were not subsequently made knights bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system.

Knights Bachelor are th ...

to entitle them to the prefix ''Sir'', which often came with appointments to that foreign order (though Herschel was later created a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

).

"Declinarians", learned societies and the BAAS

Babbage now emerged as apolemicist

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

. One of his biographers notes that all his books contain a "campaigning element". His ''Reflections on the Decline of Science and some of its Causes'' (1830) stands out, however, for its sharp attacks. It aimed to improve British science, and more particularly to oust Davies Gilbert as President of the Royal Society, which Babbage wished to reform. It was written out of pique, when Babbage hoped to become the junior secretary of the Royal Society, as Herschel was the senior, but failed because of his antagonism to Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several Chemical element, e ...

. Michael Faraday had a reply written, by Gerrit Moll

Gerard "Gerrit" Moll LLD (1785–1838) was a Dutch scientist and mathematician. A polymath in his interests, he published in four languages.

Life

From a family background in Amsterdam of commerce, Moll was drawn towards science. His teacher at the ...

, as ''On the Alleged Decline of Science in England'' (1831). On the front of the Royal Society Babbage had no impact, with the bland election of the Duke of Sussex

Duke of Sussex is a substantive title, one of several Royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom, royal dukedoms in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It is a hereditary title of a specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. It has been c ...

to succeed Gilbert the same year. As a broad manifesto, on the other hand, his ''Decline'' led promptly to the formation in 1831 of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

(BAAS).

The '' Mechanics' Magazine'' in 1831 identified as Declinarians the followers of Babbage. In an unsympathetic tone it pointed out David Brewster

Sir David Brewster Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order, KH President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, PRSE Fellow of the Royal Society of London, FRS Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, FSA Scot Fellow of the Scottish Society of ...

writing in the ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'' as another leader; with the barb that both Babbage and Brewster had received public money.

In the debate of the period on statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

(''qua'' data collection) and what is now statistical inference

Statistical inference is the process of using data analysis to infer properties of an underlying probability distribution.Upton, G., Cook, I. (2008) ''Oxford Dictionary of Statistics'', OUP. . Inferential statistical analysis infers properties of ...

, the BAAS in its Statistical Section (which owed something also to Whewell) opted for data collection. This Section was the sixth, established in 1833 with Babbage as chairman and John Elliot Drinkwater

John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune (1801–1851) was an English educator, mathematician and polyglot known for promoting women's education in India. He was the founder of Calcutta Female School (now known as Bethune College) in Calcutta, which is ...

as secretary. The foundation of the Statistical Society followed. Babbage was its public face, backed by Richard Jones and Robert Malthus.

''On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures''

Babbage published ''On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures'' (1832), on the organisation ofindustrial production

Industrial production is a measure of output of the industrial sector of the economy. The industrial sector includes manufacturing, mining, and utilities. Although these sectors contribute only a small portion of gross domestic product (GDP), they ...

. It was an influential early work of operational research. John Rennie the Younger in addressing the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

on manufacturing in 1846 mentioned mostly surveys in encyclopaedias, and Babbage's book was first an article in the ''Encyclopædia Metropolitana

''The Encyclopædia Metropolitana'' was an encyclopedic work published in London, from 1817 to 1845, by part publication. In all it came to quarto, 30 vols., having been issued in 59 parts (22,426 pages, 565 plates).

Origins

Initially the pro ...

'', the form in which Rennie noted it, in the company of related works by John Farey Jr.

John Farey Jr. (20 March 1791 – 17 July 1851) was an English mechanical engineering, mechanical engineer, Engineering consulting, consulting engineer and patent attorney, known for his pioneering contributions in the field of mechanical engine ...

, Peter Barlow and Andrew Ure. From ''An essay on the general principles which regulate the application of machinery to manufactures and the mechanical arts'' (1827), which became the ''Encyclopædia Metropolitana'' article of 1829, Babbage developed the schematic classification of machines that, combined with discussion of factories, made up the first part of the book. The second part considered the "domestic and political economy" of manufactures.

The book sold well, and quickly went to a fourth edition (1836). Babbage represented his work as largely a result of actual observations in factories, British and abroad. It was not, in its first edition, intended to address deeper questions of political economy; the second (late 1832) did, with three further chapters including one on piece rate

Piece work or piecework is any type of employment in which a worker is paid a fixed piece rate for each unit produced or action performed, regardless of time.

Context

When paying a worker, employers can use various methods and combinations of m ...

. The book also contained ideas on rational design in factories, and profit sharing

Profit sharing refers to various incentive plans introduced by businesses which provide direct or indirect payments to employees, often depending on the company's profitability, employees' regular salaries, and bonuses. In publicly traded compa ...

.

"Babbage principle"

In ''Economy of Machinery'' was described what is now called the "Babbage principle". It pointed out commercial advantages available with more carefuldivision of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise ( specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialised capabilities, a ...

. As Babbage himself noted, it had already appeared in the work of Melchiorre Gioia

Melchiorre Gioja (10 September 1767 – 2 January 1829) was an Italian writer on philosophy and political economy. His name is spelled Gioia in modern Italian.

Biography

Gioja was born at Piacenza, in what is now northern Italy.

Originally ...

in 1815. The term was introduced in 1974 by Harry Braverman

Harry Braverman (December 9, 1920 – August 2, 1976)

Agitating during the Red Scare

After serving in the shipbuilding industry during World War II, Braverman began to deepen his commitment to revolutionary struggle, joining the first Trotskyis ...

. Related formulations are the "principle of multiples" of Philip Sargant Florence, and the "balance of processes".

What Babbage remarked is that skilled workers typically spend parts of their time performing tasks that are below their skill level. If the labour process can be divided among several workers, labour costs may be cut by assigning only high-skill tasks to high-cost workers, restricting other tasks to lower-paid workers. He also pointed out that training or apprenticeship can be taken as fixed costs; but that returns to scale

In economics, the concept of returns to scale arises in the context of a firm's production function. It explains the long-run linkage of increase in output (production) relative to associated increases in the inputs (factors of production).

In th ...

are available by his approach of standardisation of tasks, therefore again favouring the factory system

The factory system is a method of manufacturing whereby workers and manufacturing equipment are centralized in a factory, the work is supervised and structured through a division of labor, and the manufacturing process is mechanized.

Because ...

. His view of human capital

Human capital or human assets is a concept used by economists to designate personal attributes considered useful in the production process. It encompasses employee knowledge, skills, know-how, good health, and education. Human capital has a subs ...

was restricted to minimising the time period for recovery of training costs.

Publishing

Another aspect of the work was its detailed breakdown of the cost structure of book publishing. Babbage took the unpopular line, from the publishers' perspective, of exposing the trade's profitability. He went as far as to name the organisers of the trade's restrictive practices. Twenty years later he attended a meeting hosted by John Chapman to campaign against the Booksellers Association, still acartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collaborate with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers ...

.

Influence

It has been written that "what Arthur Young was to agriculture, Charles Babbage was to the factory visit and machinery". Babbage's theories are said to have influenced the layout of the 1851 Great Exhibition, and his views had a strong effect on his contemporaryGeorge Julius Poulett Scrope

George Julius Poulett Scrope Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (10 March 1797 – 19 January 1876) was an English geologist and political economist as well as a Member of Parliament and magistrate for Stroud in Gloucestershire.

While an und ...

. Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

argued that the source of the productivity

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proce ...

of the factory system was exactly the combination of the division of labour with machinery, building on Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, Babbage and Ure. Where Marx picked up on Babbage and disagreed with Smith was on the motivation for division of labour by the manufacturer: as Babbage did, he wrote that it was for the sake of profitability

In economics, profit is the difference between revenue that an economic entity has received from its outputs and total costs of its inputs, also known as surplus value. It is equal to total revenue minus total cost, including both Explicit co ...

, rather than productivity, and identified an impact on the concept of a trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

.

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

went further, to oppose completely what manufacturing in Babbage's sense stood for. Babbage also affected the economic thinking of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

. George Holyoake

George Jacob Holyoake (13 April 1817 – 22 January 1906) was an English secularist, British co-operative movement, co-operator and newspaper editor. He coined the terms secularism in 1851 and "jingoism" in 1878. He edited a secularist paper, '' ...

saw Babbage's detailed discussion of profit sharing as substantive, in the tradition of Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist, political philosopher and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement, co-operative movement. He strove to ...

and Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (; ; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have be ...

, if requiring the attentions of a benevolent captain of industry

In the 19th century, a captain of industry was a business leader whose means of amassing a personal fortune contributed positively to the country in some way. This may have been through increased productivity, expansion of markets, providing more ...

, and ignored at the time.

Charles Babbage's Saturday night soirées, held from 1828 into the 1840s, were important gathering places for prominent scientists, authors and aristocracy. Babbage is credited with importing the "scientific soirée" from France with his well-attended Saturday evening soirées.

Works by Babbage and Ure were published in French translation in 1830; ''On the Economy of Machinery'' was translated in 1833 into French by Édouard Biot

Édouard Constant Biot (; July 2, 1803 – March 12, 1850) was a French engineer and Sinologist. As an engineer, he participated in the construction of the second line of French railway between Lyon and St Etienne, and as a Sinologist, publi ...

, and into German the same year by Gottfried Friedenberg. The French engineer and writer on industrial organisation Léon Lalanne was influenced by Babbage, but also by the economist Claude Lucien Bergery, in reducing the issues to "technology". William Jevons connected Babbage's "economy of labour" with his own labour experiments of 1870. The Babbage principle is an inherent assumption in Frederick Winslow Taylor

Frederick Winslow Taylor (March 20, 1856 – March 21, 1915) was an American mechanical engineer. He was widely known for his methods to improve industrial efficiency. He was one of the first management consulting, management consultants. In 190 ...

's scientific management

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineer ...

.

Mary Everest Boole claimed that there was profound influence – via her uncle George Everest – of Indian thought in general and Indian logic

The development of Indian logic dates back to the Chandahsutra of Pingala and '' anviksiki'' of Medhatithi Gautama (c. 6th century BCE); the Sanskrit grammar rules of Pāṇini (c. 5th century BCE); the Vaisheshika school's analysis of atomism (c. ...

, in particular, on Babbage and on her husband George Boole

George Boole ( ; 2 November 1815 – 8 December 1864) was a largely self-taught English mathematician, philosopher and logician, most of whose short career was spent as the first professor of mathematics at Queen's College, Cork in Ireland. H ...

, as well as on Augustus De Morgan

Augustus De Morgan (27 June 1806 – 18 March 1871) was a British mathematician and logician. He is best known for De Morgan's laws, relating logical conjunction, disjunction, and negation, and for coining the term "mathematical induction", the ...

:

Think what must have been the effect of the intense Hinduizing of three such men as Babbage, De Morgan, and George Boole on the mathematical atmosphere of 1830–65. What share had it in generating theVector Analysis Vector calculus or vector analysis is a branch of mathematics concerned with the differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in three-dimensional Euclidean space, \mathbb^3. The term ''vector calculus'' is sometimes used as a ...and the mathematics by which investigations in physical science are now conducted?

Natural theology

In 1837, responding to the series of eight ''Bridgewater Treatises

The Bridgewater Treatises (1833–36) are a series of eight works that were written by leading scientific figures appointed by the President of the Royal Society in fulfilment of a bequest of £8000, made by Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl of Bridg ...

'', Babbage published his ''Ninth Bridgewater Treatise

The Ninth Bridgewater Treatise was published by the mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage in 1837 as a response to the eight Bridgewater Treatises that the Earl of Bridgewater, Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl, had funded. The Bridgewater Trea ...

'', under the title ''On the Power, Wisdom and Goodness of God, as manifested in the Creation''. In this work Babbage weighed in on the side of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

in a current debate. He preferred the conception of creation in which a God-given natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

dominated, removing the need for continuous "contrivance".

The book is a work of natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

, and incorporates extracts from related correspondence of Herschel with Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

. Babbage put forward the thesis that God had the omnipotence and foresight to create as a divine legislator. In this book, Babbage dealt with relating interpretations between science and religion; on the one hand, he insisted that "there exists no fatal collision between the words of Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

and the facts of nature;" on the other hand, he wrote that the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

was not meant to be read literally in relation to scientific terms. Against those who said these were in conflict, he wrote "that the contradiction they have imagined can have no real existence, and that whilst the testimony of Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

remains unimpeached, we may also be permitted to confide in the testimony of our senses."

The ''Ninth Bridgewater Treatise'' was quoted extensively in '' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation''. The parallel with Babbage's computing machines is made explicit, as allowing plausibility to the theory that transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

could be pre-programmed.

Jonar Ganeri, author of ''Indian Logic'', believes Babbage may have been influenced by Indian thought; one possible route would be through

Jonar Ganeri, author of ''Indian Logic'', believes Babbage may have been influenced by Indian thought; one possible route would be through Henry Thomas Colebrooke

Henry Thomas Colebrooke FRS FRSE FLS (15 June 1765 – 10 March 1837) was an English orientalist and botanist. He has been described as "the first great Sanskrit scholar in Europe".

Biography

Henry Thomas Colebrooke was born on 15 June ...

. Mary Everest Boole argues that Babbage was introduced to Indian thought in the 1820s by her uncle George Everest:

Some time about 1825, verestcame to England for two or three years, and made a fast and lifelong friendship with Herschel and with Babbage, who was then quite young. I would ask any fair-minded mathematician to read Babbage's Ninth Bridgewater Treatise and compare it with the works of his contemporaries in England; and then ask himself whence came the peculiar conception of the nature of miracle which underlies Babbage's ideas of Singular Points on Curves (Chap, viii) – from European Theology or Hindu Metaphysic? Oh! how the English clergy of that day hated Babbage's book!

Religious views

Babbage was raised in the Protestant form of the Christian faith, his family having inculcated in him an orthodox form of worship. He explained: Rejecting the Athanasian Creed as a "direct contradiction in terms", in his youth he looked toSamuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley. Clarke's altered, Nontrinitarian revision of the 1 ...

's works on religion, of which ''Being and Attributes of God'' (1704) exerted a particularly strong influence on him. Later in life, Babbage concluded that "the true value of the Christian religion rested, not on speculative heology... but ... upon those doctrines of kindness and benevolence which that religion claims and enforces, not merely in favour of man himself but of every creature susceptible of pain or of happiness."

In his autobiography ''Passages from the Life of a Philosopher'' (1864), Babbage wrote a whole chapter on the topic of religion, where he identified three sources of divine knowledge:

# ''A priori'' or mystical experience

# From Revelation

# From the examination of the works of the Creator

He stated, on the basis of the design argument, that studying the works of nature had been the more appealing evidence, and the one which led him to actively profess the existence of God

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God (with the same or similar arguments also generally being used when talking about the exis ...

. Advocating for natural theology, he wrote:

Like Samuel Vince, Babbage also wrote a defence of the belief in divine miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

s. Against objections previously posed by David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, Babbage advocated for the belief of divine agency, stating "we must not measure the credibility or incredibility of an event by the narrow sphere of our own experience, nor forget that there is a Divine energy which overrides what we familiarly call the laws of nature." He alluded to the limits of human experience, expressing: "all that we see in a miracle is an effect which is new to our observation, and whose cause is concealed. The cause may be beyond the sphere of our observation, and would be thus beyond the familiar sphere of nature; but this does not make the event a violation of any law of nature. The limits of man's observation lie within very narrow boundaries, and it would be arrogance to suppose that the reach of man's power is to form the limits of the natural world."

Later life

The British Association was consciously modelled on the Deutsche Naturforscher-Versammlung, founded in 1822. It rejected romantic science as well as

The British Association was consciously modelled on the Deutsche Naturforscher-Versammlung, founded in 1822. It rejected romantic science as well as metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, and started to entrench the divisions of science from literature, and professionals from amateurs. Belonging as he did to the "Wattite" faction in the BAAS, represented in particular by James Watt the younger, Babbage identified closely with industrialists. He wanted to go faster in the same directions, and had little time for the more gentlemanly component of its membership. Indeed, he subscribed to a version of conjectural history that placed industrial society

In sociology, an industrial society is a society driven by the use of technology and machinery to enable mass production, supporting a large population with a high capacity for division of labour. Such a structure developed in the Western world ...

as the culmination of human development (and shared this view with Herschel). A clash with Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigating and desc ...

led in 1838 to his withdrawal from further involvement. At the end of the same year he sent in his resignation as Lucasian professor, walking away also from the Cambridge struggle with Whewell. His interests became more focussed, on computation and metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of Unit of measurement, units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to stan ...

, and on international contacts.

Metrology programme

A project announced by Babbage was to tabulate allphysical constant

A physical constant, sometimes fundamental physical constant or universal constant, is a physical quantity that cannot be explained by a theory and therefore must be measured experimentally. It is distinct from a mathematical constant, which has a ...

s (referred to as "constants of nature", a phrase in itself a neologism), and then to compile an encyclopaedic work of numerical information. He was a pioneer in the field of "absolute measurement". His ideas followed on from those of Johann Christian Poggendorff

Johann Christian Poggendorff (29 December 1796 – 24 January 1877) was a German physicist born in Hamburg. By far the greater and more important part of his work related to electricity and magnetism. Poggendorff is known for his electrostatic mo ...

, and were mentioned to Brewster in 1832. There were to be 19 categories of constants, and Ian Hacking

Ian MacDougall Hacking (February 18, 1936 – May 10, 2023) was a Canadian philosopher specializing in the philosophy of science. Throughout his career, he won numerous awards, such as the Killam Prize for the Humanities and the Balzan Prize, ...

sees these as reflecting in part Babbage's "eccentric enthusiasms". Babbage's paper ''On Tables of the Constants of Nature and Art'' was reprinted by the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1856, with an added note that the physical tables of Arnold Henry Guyot "will form a part of the important work proposed in this article".

Exact measurement was also key to the development of machine tools. Here again Babbage is considered a pioneer, with Henry Maudslay, William Sellers, and Joseph Whitworth.

Engineer and inventor

Through the Royal Society Babbage acquired the friendship of the engineer Marc Brunel. It was through Brunel that Babbage knew of Joseph Clement, and so came to encounter the artisans whom he observed in his work on manufactures. Babbage provided an introduction for Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1830, for a contact with the proposed Bristol & Birmingham Railway. He carried out studies, around 1838, to show the superiority of the broad gauge for railways, used by Brunel's Great Western Railway. In 1838, Babbage invented the cowcatcher, pilot (also called a cow-catcher), the metal frame attached to the front of locomotives that clears the tracks of obstacles; he also constructed a dynamometer car. His eldest son, Benjamin Herschel Babbage, worked as an engineer for Brunel on the railways before emigrating to Australia in the 1850s. Babbage also invented an ophthalmoscope, which he gave to Thomas Wharton Jones for testing. Jones, however, ignored it. The device only came into use after being independently invented by Hermann von Helmholtz.Cryptography

Babbage achieved notable results in cryptography, though this was still not known a century after his death. Letter frequency was category 18 of Babbage's tabulation project. Joseph Henry later defended interest in it, in the absence of the facts, as relevant to the management of movable type. As early as 1845, Babbage had solved a cipher that had been posed as a challenge by his nephew Henry Hollier, and in the process, he made a discovery about ciphers that were based on Vigenère tables. Specifically, he realised that enciphering plain text with a keyword rendered the cipher text subject to modular arithmetic. During the Crimean War of the 1850s, Babbage broke Vigenère's autokey cipher as well as the much weaker cipher that is called Vigenère cipher today. His discovery was kept a military secret, and was not published. Credit for the result was instead given to Friedrich Kasiski, a Prussian infantry officer, who made the same discovery some years later. However, in 1854, Babbage published the solution of a Vigenère cipher, which had been published previously in the ''Journal of the Society of Arts''. In 1855, Babbage also published a short letter, "Cypher Writing", in the same journal. Nevertheless, his priority was not established until 1985.Public nuisances

Babbage involved himself in well-publicised but unpopular campaigns against public nuisances. He once counted all the broken panes of glass of a factory, publishing in 1857 a "Table of the Relative Frequency of the Causes of Breakage of Plate Glass Windows": Of 464 broken panes, 14 were caused by "drunken men, women or boys". Babbage's distaste for commoners (the Mob) included writing "Observations of Street Nuisances" in 1864, as well as tallying up 165 "nuisances" over a period of 80 days. He especially hated busking, street music, and in particular the music of organ grinders, against whom he railed in various venues. The following quotation is typical: Babbage was not alone in his campaign. A convert to the cause was the MP Michael Thomas Bass. In the 1860s, Babbage also took up the anti-Hoop rolling#British Empire, hoop-rolling campaign. He blamed hoop-rolling boys for driving their iron hoops under horses' legs, with the result that the rider is thrown and very often the horse breaks a leg. Babbage achieved a certain notoriety in this matter, being denounced in debate in Commons in 1864 for "commencing a crusade against the popular game of tip-cat and the trundling of hoops."Computing pioneer

Babbage's machines were among the first mechanical computers. That they were not actually completed was largely because of funding problems and clashes of personality, most notably with George Biddell Airy, the Astronomer Royal.

Babbage directed the building of some steam-powered machines that achieved some modest success, suggesting that calculations could be mechanised. For more than ten years he received government funding for his project, which amounted to £17,000, but eventually the Treasury lost confidence in him.

While Babbage's machines were mechanical and unwieldy, their basic architecture was similar to that of a modern computer. The data and program memory were separated, operation was instruction-based, the control unit could make conditional jumps, and the machine had a separate Input/output, I/O unit.

Babbage's machines were among the first mechanical computers. That they were not actually completed was largely because of funding problems and clashes of personality, most notably with George Biddell Airy, the Astronomer Royal.

Babbage directed the building of some steam-powered machines that achieved some modest success, suggesting that calculations could be mechanised. For more than ten years he received government funding for his project, which amounted to £17,000, but eventually the Treasury lost confidence in him.

While Babbage's machines were mechanical and unwieldy, their basic architecture was similar to that of a modern computer. The data and program memory were separated, operation was instruction-based, the control unit could make conditional jumps, and the machine had a separate Input/output, I/O unit.

Background on mathematical tables

In Babbage's time, printed mathematical tables were calculated by human computers; in other words, by hand. They were central to navigation, science and engineering, as well as mathematics. Mistakes were known to occur in transcription as well as calculation. At Cambridge, Babbage saw the fallibility of this process, and the opportunity of adding mechanisation into its management. His own account of his path towards mechanical computation references a particular occasion: There was another period, seven years later, when his interest was aroused by the issues around computation of mathematical tables. The French official initiative by Gaspard de Prony, and its problems of implementation, were familiar to him. After the Napoleonic Wars came to a close, scientific contacts were renewed on the level of personal contact: in 1819 Charles Blagden was in Paris looking into the printing of the stalled de Prony project, and lobbying for the support of the Royal Society. In works of the 1820s and 1830s, Babbage referred in detail to de Prony's project.Difference engine

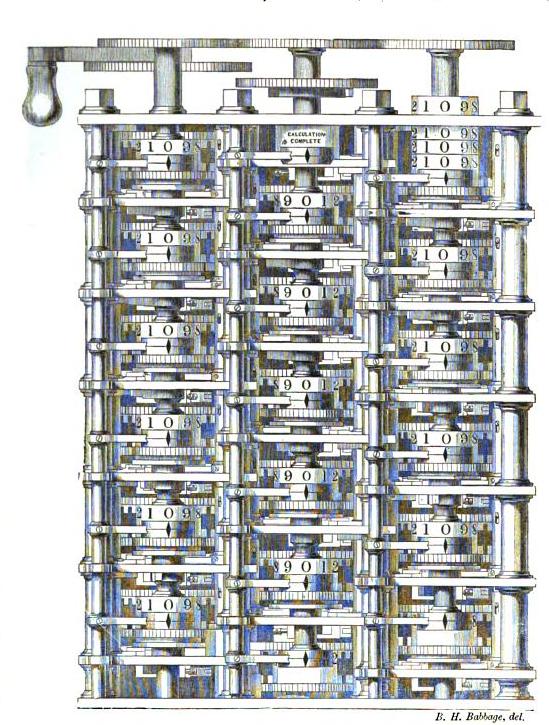

Babbage began in 1822 with what he called the difference engine, made to compute values of polynomial functions. It was created to calculate a series of values automatically. By using the method of finite differences, it was possible to avoid the need for multiplication and division.

For a prototype difference engine, Babbage brought in Joseph Clement to implement the design, in 1823. Clement worked to high standards, but his machine tools were particularly elaborate. Under the standard terms of business of the time, he could charge for their construction, and would also own them. He and Babbage fell out over costs around 1831.

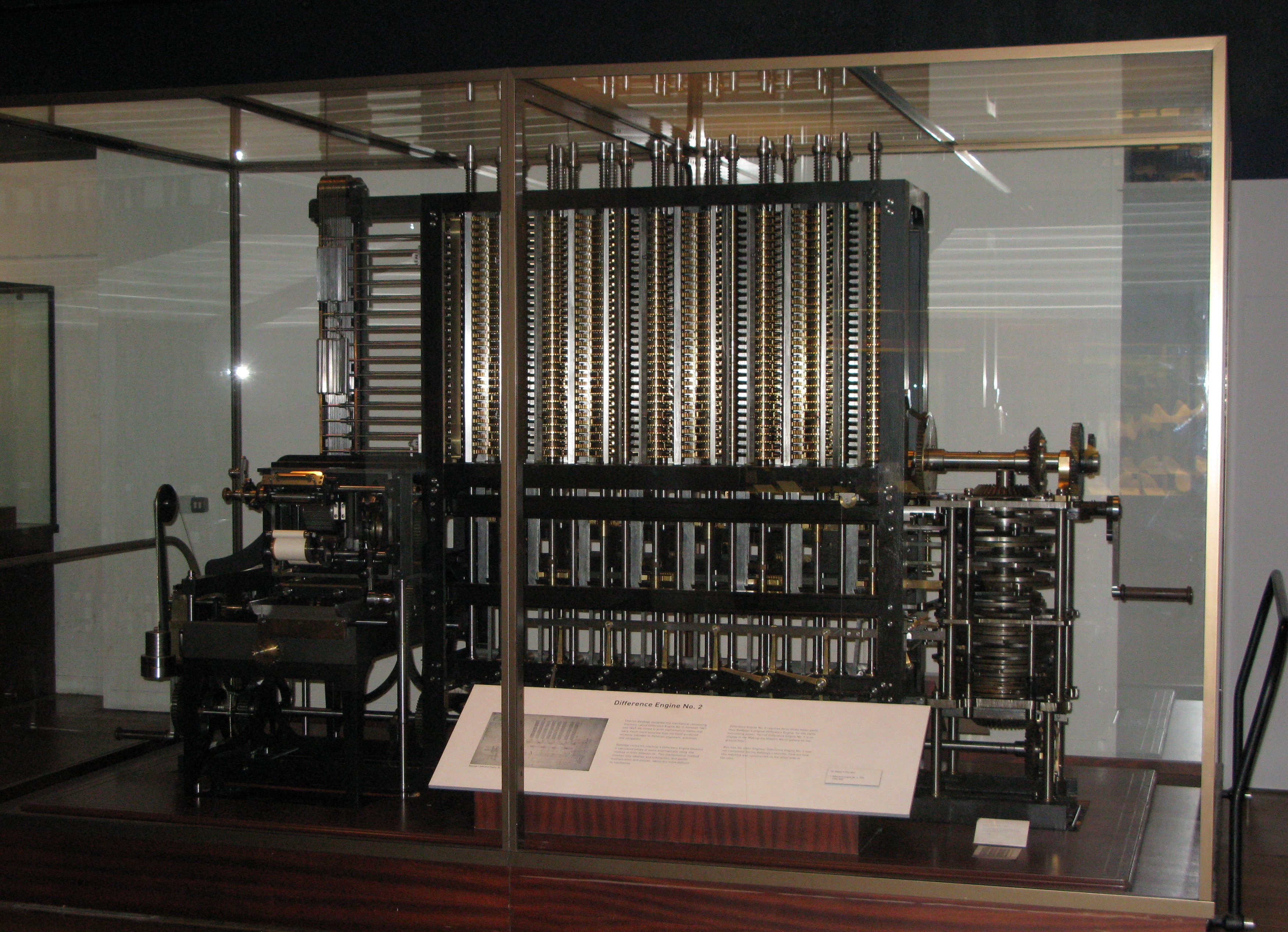

Some parts of the prototype survive in the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. This prototype evolved into the "first difference engine". It remained unfinished and the finished portion is located at the Science Museum in London. This first difference engine would have been composed of around 25,000 parts, weighed , and would have been tall. Although Babbage received ample funding for the project, it was never completed. He later (1847–1849) produced detailed drawings for an improved version,"Difference Engine No. 2", but did not receive funding from the British government. His design was finally constructed in 1989–1991, using his plans and 19th-century manufacturing tolerances. It performed its first calculation at the Science Museum, London, returning results to 31 digits.

Nine years later, in 2000, the Science Museum completed the computer printer, printer Babbage had designed for the difference engine. His printers were the first computer printers invented.

Babbage began in 1822 with what he called the difference engine, made to compute values of polynomial functions. It was created to calculate a series of values automatically. By using the method of finite differences, it was possible to avoid the need for multiplication and division.

For a prototype difference engine, Babbage brought in Joseph Clement to implement the design, in 1823. Clement worked to high standards, but his machine tools were particularly elaborate. Under the standard terms of business of the time, he could charge for their construction, and would also own them. He and Babbage fell out over costs around 1831.

Some parts of the prototype survive in the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. This prototype evolved into the "first difference engine". It remained unfinished and the finished portion is located at the Science Museum in London. This first difference engine would have been composed of around 25,000 parts, weighed , and would have been tall. Although Babbage received ample funding for the project, it was never completed. He later (1847–1849) produced detailed drawings for an improved version,"Difference Engine No. 2", but did not receive funding from the British government. His design was finally constructed in 1989–1991, using his plans and 19th-century manufacturing tolerances. It performed its first calculation at the Science Museum, London, returning results to 31 digits.

Nine years later, in 2000, the Science Museum completed the computer printer, printer Babbage had designed for the difference engine. His printers were the first computer printers invented.

Completed models

The Science Museum has constructed two Difference Engines according to Babbage's plans for the Difference Engine No 2. One is owned by the museum. The other, owned by the technology multimillionaire Nathan Myhrvold, went on exhibition at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California on 10 May 2008. The two models that have been constructed are not replicas.Analytical Engine

After the attempt at making the first difference engine fell through, Babbage worked to design a more complex machine called the Analytical Engine. He hired C. G. Jarvis, who had previously worked for Clement as a draughtsman. The Analytical Engine marks the transition from mechanised arithmetic to fully-fledged general purpose computation. It is largely on it that Babbage's standing as computer pioneer rests. The major innovation was that the Analytical Engine was to be programmed using punched cards: the Engine was intended to use loops of Jacquard loom, Jacquard's punched cards to control a mechanical calculator, which could use as input the results of preceding computations. The machine was also intended to employ several features subsequently used in modern computers, including sequential control, branching and looping. It would have been the first mechanical device to be, in principle, Turing-complete. Charles Babbage wrote a series of programs for the Analytical Engine from 1837 to 1840. The first program was finished in 1837. The Engine was not a single physical machine, but rather a succession of designs that Babbage tinkered with until his death in 1871.

Ada Lovelace and Italian followers

Ada Lovelace, who corresponded with Babbage during his development of the Analytical Engine, is credited with developing an algorithm that would enable the Engine to calculate a sequence of Bernoulli numbers.Robin Hammerman, Andrew L. Russell (2016). ''Ada's Legacy: Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the Digital Age''. Association for Computing Machinery and Morgan & Claypool Publishers. Despite documentary evidence in Lovelace's own handwriting, some scholars dispute to what extent the ideas were Lovelace's own. For this achievement, she is often described as the first programmer, computer programmer; though no programming language had yet been invented. Lovelace also translated and wrote literature supporting the project. Describing the engine's programming by punch cards, she wrote: "We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as theJacquard loom

The Jacquard machine () is a device fitted to a loom that simplifies the process of manufacturing textiles with such complex patterns as brocade, damask and matelassé. The resulting ensemble of the loom and Jacquard machine is then called a Jac ...

weaves flowers and leaves."

Babbage visited Turin in 1840 at the invitation of Giovanni Plana, who had developed in 1831 an analog computing machine that served as a Cappella dei Mercanti, Turin, perpetual calendar. Here in 1840 in Turin, Babbage gave the only public explanation and lectures about the Analytical Engine. In 1842 Charles Wheatstone approached Lovelace to translate a paper of Luigi Menabrea, who had taken notes of Babbage's Turin talks; and Babbage asked her to add something of her own. Fortunato Prandi who acted as interpreter in Turin was an Italian exile and follower of Giuseppe Mazzini.

Swedish followers

Per Georg Scheutz wrote about the difference engine in 1830, and experimented in automated computation. After 1834 and Lardner's ''Edinburgh Review'' article he set up a project of his own, doubting whether Babbage's initial plan could be carried out. This he pushed through with his son, Edvard Scheutz. Another Swedish engine was that of Martin Wiberg (1860).Legacy

In 2011, researchers in Britain proposed a multimillion-pound project, "Plan 28", to construct Babbage's Analytical Engine. Since Babbage's plans were continually being refined and were never completed, they intended to engage the public in the project and crowdsourcing, crowd-source the analysis of what should be built. It would have the equivalent of 675 bytes of memory, and run at a clock speed of about 7 Hz. They hoped to complete it by the 150th anniversary of Babbage's death, in 2021. Advances in microelectromechanical system, MEMS and nanotechnology have led to recent high-tech experiments in mechanical computation. The benefits suggested include operation in high radiation or high temperature environments. These modern versions of mechanical computation were highlighted in ''The Economist'' in its special "end of the millennium" black cover issue in an article entitled "Babbage's Last Laugh". Due to his association with the town Babbage was chosen in 2007 to appear on the 5 Totnes pound note. An image of Babbage features in the British culture, British cultural icons section of the newly designed British passport in 2015.Family

On 25 July 1814, Babbage married Georgiana Whitmore, sister of British parliamentarian William Wolryche-Whitmore, at St. Michael's Church in Teignmouth, Devon. The couple lived at Dudmaston Hall, Shropshire (where Babbage engineered the central heating system), before moving to 5 Devonshire Street, London in 1815.

Charles and Georgiana had eight children, but only four – Benjamin Herschel Babbage, Benjamin Herschel, Georgiana Whitmore, Dugald Bromhead Babbage, Dugald Bromhead and Henry Prevost – survived childhood. Charles' wife Georgiana died in Worcester, England, Worcester on 1 September 1827, the same year as his father, their second son (also named Charles) and their newborn son Alexander.

* Benjamin Herschel Babbage (1815–1878)

* Charles Whitmore Babbage (1817–1827)

* Georgiana Whitmore Babbage (1818 – 26 September 1834)

* Edward Stewart Babbage (1819–1821)

* Francis Moore Babbage (1821–????)

* Dugald Bromhead (Bromheald?) Babbage (1823–1901)

* (Maj-Gen) Henry Prevost Babbage (1824–1918)

* Alexander Forbes Babbage (1827–1827)

His youngest surviving son, Henry Prevost Babbage (1824–1918), went on to create six small demonstration pieces for Difference Engine No. 1 based on his father's designs, one of which was sent to Harvard University where it was later discovered by Howard H. Aiken, pioneer of the Harvard Mark I. Henry Prevost's 1910 Analytical Engine Mill, previously on display at Dudmaston Hall, is now on display at the Science Museum.