Australian folklore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Australian folklore refers to the

* Gippsland phantom cat – An urban legend centred on the idea that when United States soldiers were based in Victoria during

* Gippsland phantom cat – An urban legend centred on the idea that when United States soldiers were based in Victoria during

* My Country – More commonly known as "I Love a Sunburnt Country" is a patriotic poem about Australia published in 1908 written by

* My Country – More commonly known as "I Love a Sunburnt Country" is a patriotic poem about Australia published in 1908 written by

*

*

*

*

, – Meacham, Steve, '' *

*

* Franklin House – Historic house in Launceston that has had reports of ghost sightings.

*

* Franklin House – Historic house in Launceston that has had reports of ghost sightings.

* *

*

*

*

*

*

* 5 o'clock wave – Supposedly a large wave, several metres in height and created by the daily release of dam overflow, that is said to travel downriver at high speed, and to reach the location at which the tale is being told at 5 o'clock each afternoon.

* ANZAC spirit – Idea shared by Australian &

* 5 o'clock wave – Supposedly a large wave, several metres in height and created by the daily release of dam overflow, that is said to travel downriver at high speed, and to reach the location at which the tale is being told at 5 o'clock each afternoon.

* ANZAC spirit – Idea shared by Australian &  *

* * Mahogany Ship – A supposed wrecked Portuguese caravel which is purported to lie beneath the sand approximately six miles west of Warrnambool in southwest Victoria, Australia.

*

* Mahogany Ship – A supposed wrecked Portuguese caravel which is purported to lie beneath the sand approximately six miles west of Warrnambool in southwest Victoria, Australia.

*

folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

and urban legends

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

that have evolved in Australia from Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia 50,000 to 65,000 year ...

myths to colonial and contemporary

Contemporary history, in English-language historiography, is a subset of modern history that describes the historical period from about 1945 to the present. In the social sciences, contemporary history is also continuous with, and related t ...

folklore including people

The term "the people" refers to the public or Common people, common mass of people of a polity. As such it is a concept of human rights law, international law as well as constitutional law, particularly used for claims of popular sovereignty. I ...

, places and events, that have played part in shaping the culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

, image and traditions that are seen in contemporary Old Australia.

Definitions

Folklore: 1. The traditional beliefs, myths, tales, and practices of a people, transmitted orally. 2. The comparative study of folk knowledge and culture. 3. A body of widely accepted but usually specious notions about a place, a group, or an institution. Intangible culture: Traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts. Traditional cultural expressions (TCEs or TECs), also called 'expressions of folklore': may include music, dance, art, designs, names, signs and symbols, performances, ceremonies, architectural forms, handicrafts and narratives, or many other artistic or cultural expressions.Collections of Australian Folklore

Australian folklore is preserved as part of The Australian Register Unesco Memory of the World Program and the Oral History and Folklore collection of theNational Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia (NLA), formerly the Commonwealth National Library and Commonwealth Parliament Library, is the largest reference library in Australia, responsible under the terms of the ''National Library Act 1960'' for "mainta ...

.

Playlore

Australian Children’s Folklore Collection inMuseum Victoria

Museums Victoria is an organisation that includes a number of museums and related bodies in Melbourne. These include Melbourne Museum, Immigration Museum, Scienceworks (Melbourne), Scienceworks, IMAX Melbourne, a research institute, the UNESCO W ...

, coordinated by Dr June Factor and Dr Gwenda Davey.

Music

John Meredith Folklore Collection 1953-1994, held in the National Library of Australia. Rob and Olya Willis Folklore collection. O'Connor Collection. Scott Collection. Australian Traditional Music Archive. Australian Folk SongsDance

Various books on folk dancing in AustraliaSpoken word

Warren Fahey

Warren John Fahey AM (born 3 January 1946) is an Australian folklore collector, cultural historian, author, actor, broadcaster, record and concert producer, visual artist, songwriter, and performer of Australian traditional and related historic ...

Collection.

Australian Fairy Tale Society

History of Australian folklore collection

Source: *1905 ''Old Bush Songs'' byBanjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author, widely considered one of the greatest writers of Australia's colonial period.

Born in rural New South Wales, Paterson worke ...

*1952 Bush Music Club (Sydney)

*1953 Victorian Folk Lore Society

*1958 ''The Australian Legend'' by Russel Ward

Russel Braddock Ward AM (9 November 1914 – 13 August 1995) was an Australian historian. He is best known for ''The Australian Legend'' (1958), an examination of the development of the " Australian character", which was awarded the Ernest Sc ...

*''1963-1975 Australian Tradition'' magazine edited by Wendy Lowenstein

*1964 Folklore Council of Australia

*1964 ''Who Wrote the Ballads?'' by John Manifold

*1967 ''Folk Songs of Australia and the men and women who sang them'' by John Meredith

*1969 ''Folklore of the Australian Railwaymen'' by Patsy Adam-Smith

Patricia Jean Adam-Smith, (31 May 1924 – 20 September 2001) was an Australian author, historian and servicewoman. She was a prolific writer on a range of subjects covering history, folklore and the preservation of national traditions,Adelaide ...

*1974-1996 Australian Folk Trust

*1974 ''Take Your Partners'' by Shirley Andrews

Shirley Aldythea Marshall Seymour Andrews (5 November 1915 – 15 September 2001) was an Australian biochemist, dancer, researcher and Indigenous Australians, Aboriginal rights activist.

Early life and education

Andrews was born on November 5, ...

*1979 Australian Folklore Society

*1987 ''A Dictionary of Australian Folklore: Lore, Legends, Myths and Traditions'' by Bill Wannan

*1987 ''Folklife: Our Living Heritage'' report proposed the establishment of a National Folklife Centre''.'' The Centre would ‘provide national focus for action to record, safeguard and promote awareness of Australia’s heritage of folklife’. None of the 51 recommendations were implemented.

*1987-2018 ''Australian Folklore'' journal

*1993 ''The Oxford Companion to Australian Folklore'' edited by Graham Seal and Gwenda Bede Davey.

*2002 Australian Folklore Network established by Professor Graham Seal

Ongoing research into Australian folklore

Universities teaching intangible culture – * Curtin University: Australian Folklore Research Unit * Deakin University: Intangible Cultural Heritage The Australian Folklore Network holds an annual conference, the day before the National Folk Festival in Canberra each Easter. The National Library of Australia sponsors an annual National Folk Fellowship.Australian Aboriginal mythology

* Baijini – Unknown race mentioned inYolngu

The Yolngu or Yolŋu ( or ) are an aggregation of Aboriginal Australian people inhabiting north-eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. ''Yolngu'' means "person" in the Yolŋu languages. The terms Murngin, Wulamba, Yalnuma ...

folklore.

* Bora – Sacred Aboriginal initiation ceremony. Many sites still exist throughout Australia.

* Bunyip – According to legend, they are said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes.

*Dreamtime

The Dreaming, also referred to as Dreamtime, is a term devised by early anthropologists to refer to a religio-cultural worldview attributed to Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology, Australian Aboriginal mythology. It was originally u ...

– The Dreamtime to Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia (co ...

is the beginning of time, the creation of knowledge from which their culture began more than 60,000 years ago.

* Kata Tjuta – Many Dreamtime stories are told by the Pitjantjatjara

The Pitjantjatjara (; or ) are an Aboriginal people of the Central Australian desert near Uluru. They are closely related to the Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra and their languages are, to a large extent, mutually intelligible (all are v ...

people, including a mythical creature that lurks the summit.

*Lake Mungo remains

The Lake Mungo remains are three prominent sets of human remains that are Aboriginal Australian: Lake Mungo 1 (also called Mungo Woman, LM1, and ANU-618), Lake Mungo 3 (also called Mungo Man, Lake Mungo III, and LM3), and Lake Mungo 2 (LM2). ...

– Human skeletons found in 1969, believed to have lived between 40,000 and 68,000 years ago are the oldest human remains found in Australia.

*Rainbow Serpent

The Rainbow Serpent or Rainbow Snake is a common deity often seen as the Creator deity, creator God, known by numerous names in different Australian Aboriginal languages by the many List of Australian Aboriginal group names, different Aborigina ...

– It is the sometimes unpredictable Rainbow Serpent, who vies with the ever-reliable Sun, that replenishes the stores of water, forming gullies and deep channels as it slithered across the landscape, allowing for the collection and distribution of water.

* Yara-ma-yha-who – According to Myth, the creature resembles a red frog-like creature that hides in trees waiting for an unsuspecting victim to consume.

Animals and creatures

*Bob the Railway Dog

Bob the Railway Dog (also known as "Terowie, South Australia, Terowie Bob") is part of South Australian Railways folklore. He travelled the South Australian Railways system in the latter part of the 19th century, and was known widely to railwa ...

– A Dog that was remembered for traveling along the South Australian Railway.

* Booie Monster – Reports of a monster lurking in a cave first reported in the 1950s

* Drop bear – Stories of drop bears are frequently related to visiting tourists as a joke. (see also the Queensland tiger)

* Gippsland phantom cat – An urban legend centred on the idea that when United States soldiers were based in Victoria during

* Gippsland phantom cat – An urban legend centred on the idea that when United States soldiers were based in Victoria during WWII

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, they released cougars

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, '' KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North, Central and South America, making it the most widely distributed wild ...

into the wild. Consequently, many sightings of big cats have been reported across Gippsland

Gippsland () is a rural region in the southeastern part of Victoria, Australia, mostly comprising the coastal plains south of the Victorian Alps (the southernmost section of the Great Dividing Range). It covers an elongated area of east of th ...

and even in other parts of Australia.

* Hook Island Sea Monster – Gigantic, tadpole-like sea monster

Sea monsters are beings from folklore believed to dwell in the sea and are often imagined to be of immense size. Marine monsters can take many forms, including sea dragons, sea serpents, or tentacled beasts. They can be slimy and scaly and are of ...

, Photographed in Stonehaven Bay, Hook Island, Queensland.

* Megalania – A giant goanna

A goanna is any one of several species of lizard of the genus ''Monitor lizard, Varanus'' found in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Around 70 species of ''Varanus'' are known, 25 of which are found in Australia. This varied group of carnivorous r ...

(lizard), generally believed to be extinct. However, there have been numerous reports and rumours of living Megalania in Australia, and occasionally New Guinea, but the only physical evidence that Megalania might still be alive today are plaster casts of possible Megalania footprints made in 1979.

*Platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypi ...

– Native Australian animal which is one of only two mammals that lay eggs (the other being the echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the Family (biology), family Tachyglossidae , living in Australia and New Guinea. The four Extant taxon, extant species of echidnas ...

), and one of the few species of venomous mammals. Due to its unique features the scientist who initially discovered and examined the creature thought it was made of several animals sewn together and deemed it to be a hoax.

* Red Dog – A dog that was known for his long travels through Western Australia's Pilbara region.

*Tasmanian tiger

The thylacine (; binomial name ''Thylacinus cynocephalus''), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, was a carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea. Th ...

– Despite the widely held view that the thylacine (or Tasmanian tiger) became extinct during the 1930s, accounts of alleged sightings in eastern Victoria and parts of Tasmania have persisted to the present day.

* Yowie (cryptid) – In the modern context, the Yowie is the generic (and somewhat affectionate) term for an unidentified hominid reputed to lurk in the Australian wilderness, analogous to the Himalayan Yeti

The Yeti ()"Yeti"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. is an ape-like creature purported t ...

and the North American . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. is an ape-like creature purported t ...

Bigfoot

Bigfoot (), also commonly referred to as Sasquatch (), is a large, hairy Mythic humanoids, mythical creature said to inhabit forests in North America, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.Example definitions include:

*"A large, hairy, manlike ...

.

*The Dog on the Tuckerbox – an allegorical bullock driver's dog that loyally guarded the man's tuckerbox until its death. It has been immortalized in both a poem and a statue at Gundagai

Gundagai is a town in New South Wales, Australia. Although a small town, Gundagai is a popular topic for writers and has become a representative icon of a typical Australian country town. Located along the Murrumbidgee River and Muniong, Honeys ...

in southern NSW. By way of explanation – tucker means food – so a tuckerbox is a lunch box

A lunch box (or lunchbox) is a hand-held container used to transport food, usually to work or to school. It is commonly made of metal or plastic, is reasonably airtight and often has a handle for carrying.

In the United States

In the Unit ...

.

Historical events

*Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Rebellion was a series of events involving gold miners who revolted against the British administration of the colony of Victoria, Australia, during the Victorian gold rush. It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, wh ...

– A rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

that took place in Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

on 3 December 1854.

* Ancient Coins Marchinbar Island – Nine coins found, some believing they could have come from the Kilwa Sultanate

The Kilwa Sultanate was a sultanate, centered at Kilwa (an island off modern-day, Kilwa District in Lindi Region of Tanzania), whose authority, at its height, stretched over the entire length of the Swahili Coast. According to the legend, it wa ...

of east Africa which dates back to the 10th century.

* Frontier wars – A much less talked about event in Australian history, a war that spanned 146 years which was fought between mostly British settlers and Aboriginal tribes.

*First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

– Name given to the 11 ships that departed England in 1787, with convicts, officers and free settlers to found what became the first European settlement in Australia, Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

.

* Frederick escape – A ship hijacked by Australian convicts and used to sail to Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

in 1834.

* Lachlan Gold Escort robbery – One of the largest ever gold robberies in Australian history. Led by outlaw Ben Hall & Frank Gardiner

Frank Gardiner (1830 – c. 1882) was an Australian bushranger who became notorious for his lead role in the largest gold heist in Australian history, at Eugowra, New South Wales in June 1862. Gardiner and Gardiner-Hall gang, his gang, which in ...

, Most of the gold was recovered, but some still search the area for treasure. Would equate to about A$13 million in today's value.

* Nelson robbery - One of the biggest robberies during the Victorian gold rush

The Victorian gold rush was a period in the history of Victoria, Australia, approximately between 1851 and the late 1860s. It led to a period of extreme prosperity for the Australian colony and an influx of population growth and financial capi ...

, in which 8,183 ounces of gold were taken at gunpoint.

*Kokoda Track campaign

The Kokoda Track campaign or Kokoda Trail campaign was part of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign consisted of a series of battles fought between July and November 1942 in what was then the Australian Territory of Papua. It was primar ...

- Battles fought in 1942 in what was then the Australian Territory of Papua

The Territory of Papua comprised the southeastern quarter of the island of New Guinea from 1883 to 1975. In 1883, the Government of Queensland annexed this territory for the British Empire. The United Kingdom Government refused to ratify the ...

with Australian and United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

forces defeating the Japanese who directly threatened the security of Australia and is considered part of the ANZAC legend

The ANZAC spirit or ANZAC legend is a concept which suggests that Australian and New Zealand soldiers possess shared characteristics, specifically the qualities those soldiers allegedly exemplified on the battlefields of World War I. These ...

.

* Portuguese discovery of Australia – A much disputed theory that claims early Portuguese navigators were the first Europeans to sight Australia between 1521 and 1524, well before the arrival of Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ) was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. He served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 1603–1611 and 1612–1616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of Solor. During his voyage of 1605–1606 ...

in 1606.

Art, film, music and literature

*Bush ballad

The bush ballad, bush song, or bush poem is a style of poetry and folk music that depicts the life, character and scenery of the Australian bush. The typical bush ballad employs a straightforward rhyme structure to narrate a story, often one of ...

– Poems that usually depict Australian life in the outback or bush.

* Clancy of the Overflow – A poem by Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author, widely considered one of the greatest writers of Australia's colonial period.

Born in rural New South Wales, Paterson worke ...

which admires the Outback

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of Australia. The Outback is more remote than Australian bush, the bush. While often envisaged as being arid, the Outback regions extend from the northern to southern Australian coastli ...

.

*Eternity

Eternity, in common parlance, is an Infinity, infinite amount of time that never ends or the quality, condition or fact of being everlasting or eternal. Classical philosophy, however, defines eternity as what is timeless or exists outside tim ...

– A Graffiti tag done more than 500,000 times by Arthur Stace

Arthur Malcolm Stace (9 February 1885 – 30 July 1967), known as Mr Eternity, was an Australian soldier. He was an alcoholic from his teenage years until the early 1930s, when he converted to Christianity and began to spread his message b ...

over a 35-year period, of which only 2 original tags remain.

* Foo was here – Popular Graffiti signature during WW1 that was later adopted by Americans during WW2

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies and the Axis powers. Nearly all of the world's countries participated, with many nations mobilising ...

and called Kilroy was here

Kilroy was here is a meme that became popular during World War II, typically seen in graffiti. Its origin is debated, but the phrase and the distinctive accompanying doodle became associated with G.I. (military), GIs in the 1940s: a bald-head ...

. Is said to have Influenced modern Street art

Street art is visual art created in public locations for public visibility. It has been associated with the terms "independent art", "post-graffiti", "neo-graffiti" and guerrilla art.

Street art has evolved from the early forms of defiant gr ...

.

* My Country – More commonly known as "I Love a Sunburnt Country" is a patriotic poem about Australia published in 1908 written by

* My Country – More commonly known as "I Love a Sunburnt Country" is a patriotic poem about Australia published in 1908 written by Dorothea Mackellar

Isobel Marion Dorothea Mackellar (1 July 1885 – 14 January 1968) was an Australian poet and fiction writer. Her poem " My Country" is widely known in Australia, especially its second stanza, which begins: "I love a sunburnt country / ...

when she was 19 and homesick living in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

.

*''The Lucky Country

''The Lucky Country'' is a 1964 book by Donald Horne. The title has become a nickname for Australia and is generally used favourably, although the origin of the phrase was negative in the context of the book. Among other things, it has been use ...

'' – Is a book by Donald Horne

Donald Richmond Horne (26 December 1921 – 8 September 2005) was an Australian journalist, writer, social critic, and academic who became one of Australia's best known public intellectuals, from the 1960s until his death.

Horne was a proli ...

in which the phrase itself was used as sarcasm within the context of the book but has taken place in Australian culture as a true and meaningful title.

*''The Story of the Kelly Gang

''The Story of the Kelly Gang'' is a 1906 Australian bushranger film directed by Charles Tait (film director), Charles Tait. It traces the exploits of the 19th-century Kelly gang of bushrangers and outlaws, led by Ned Kelly. The silent film was ...

'' – The world's first full-length film. Made in 1906, it ran for more than an hour; it is, however, considered a Lost film

A lost film is a feature film, feature or short film in which the original negative or copies are not known to exist in any studio archive, private collection, or public archive. Films can be wholly or partially lost for a number of reasons. ...

, as only 20 minutes of the original film still exist.

* Rod Ansell – Outback Australian who became the inspiration for the famous film ''Crocodile Dundee

''Crocodile Dundee'' is a 1986 action comedy film set in the Australian Outback and in New York City. It stars Paul Hogan as the weathered Mick Dundee and American actress Linda Kozlowski as reporter Sue Charlton. Inspired by the true-life ex ...

''.

* Streets of Forbes – Folk song about iconic Bushranger Ben Hall.

*Waltzing Matilda

"Waltzing Matilda" is a song developed in the Australian style of poetry and folk music called a bush ballad. It has been described as the country's "unofficial national anthem".

The title was Australian slang for travelling on foot (waltzing ...

– Extensive folklore surrounds the song and the process of its creation, to the extent that the song has its own museum in Winton, Queensland

Winton is an outback town and locality in the Shire of Winton in Central West Queensland, Australia. It is northwest of Longreach. The main industries of the area are sheep and cattle raising. The town was named in 1876 by postmaster Rober ...

People

*

*John Batman

John Batman (21 January 18016 May 1839) was an Australian Pastoral farming, grazier, entrepreneur and explorer, who had a prominent role in the foundation of Melbourne, founding of Melbourne. He also was involved in many attacks against Indigen ...

– 19th century pioneer, controversial with how he dealt with Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

, but nevertheless signed a peaceful agreement with the Wurundjeri

The Wurundjeri people are an Aboriginal peoples, Aboriginal people of the Woiwurrung language, Woiwurrung language group, in the Kulin nation. They are the traditional owners of the Yarra River Valley, covering much of the present location of ...

known as Batman's Treaty which would eventuality lead to the Foundation of Melbourne

*

*Don Bradman

Sir Donald George Bradman (27 August 1908 – 25 February 2001), nicknamed "The Don", was an Australian international cricketer, widely acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time. His cricketing successes have been claimed by Shane ...

– one of the most renowned cricketers in history, Bradman faced a unique and unexpected conclusion to his illustrious career. Requiring just 4 runs in his final innings to achieve a remarkable test average of 100, he was surprisingly bowled for a duck, leaving him with an average of 99.94. This captivating episode has ingrained itself in Australian folklore, contributing significantly to the mystique surrounding his legacy. It is worth noting that there are unsubstantiated rumours suggesting that he may have attained the elusive 4 runs in another match, potentially miscounted in official records.

* William Buckley – Australian convict who escaped and became famous for living in an Aboriginal community for more than thirty years. Believed by many Australians to be the source of the saying "You've got Buckley's Chance".

* Azaria Chamberlain – the name of two-month-old Australian baby who disappeared on the night of 17 August 1980 on a camping trip with her family. Her parents, Lindy Chamberlain and Michael Chamberlain, reported that she had been taken from their tent by a dingo

The dingo (either included in the species ''Canis familiaris'', or considered one of the following independent taxa: ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient (basal (phylogenetics), basal) lineage ...

, but they were arrested, tried, and convicted of her murder in 1982. Both were later cleared, and thus the case is best remembered for what was an injustice. The Chamberlains were Seventh-day Adventists

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabba ...

and an urban myth had developed that they were required to sacrifice a child as part of their religious beliefs and that the name Azaria meant "sacrifice". These statements are false.

*John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

– 14th Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

. Led Australia through WW2

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies and the Axis powers. Nearly all of the world's countries participated, with many nations mobilising ...

when the country was threatened by Japanese invasion and was successful but died in office towards the end of the war. He is considered Australia's greatest Prime Minister.

* Dancing Man – unidentified man dancing in the street in Sydney, Australia, after the end of World War II.

*Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian and American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Oliv ...

– first Australian born actor to achieve significant fame in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

.

*Dawn Fraser

Dawn Fraser (born 4 September 1937) is an Australian freestyle champion swimmer, eight-time olympic medallist, a 15-year world record holder in the 100-metre freestyle, and former politician. Controversial, yet the winner of countless honours, ...

– perhaps the greatest Australian female swimmer of all time. Known for her politically incorrect

"Political correctness" (adjectivally "politically correct"; commonly abbreviated to P.C.) is a term used to describe language, policies, or measures that are intended to avoid offense or disadvantage to members of particular groups in society. ...

behaviour or larrikin

Larrikin is an Australian English term meaning "a mischievous young person, an uncultivated, rowdy but good-hearted person", or "a person who acts with apparent disregard for social or political conventions".

In the 19th and early 20th centurie ...

character as much as her athletic ability, Fraser won eight Olympic medals, including four golds, and six Commonwealth Games

The Commonwealth Games is a quadrennial international multi-sport event among athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations, which consists mostly, but not exclusively, of territories of the former British Empire. The event was first held in 1930 ...

gold medals. It was alleged that she took the flag from Emperor Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

's palace, while this was proved false, the incident became part of the folklore.

* Lennie Gwyther – 9-year-old boy famous for traveling more than 1000 km on horseback from his home in Leongatha to see the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932.

* Ben Hall - an Australian bushranger

Bushrangers were armed robbers and outlaws who resided in The bush#Australia, the Australian bush between the 1780s and the early 20th century. The original use of the term dates back to the early years of the British colonisation of Australia ...

and leading member of the Gardiner–Hall gang. He and his associates carried out many raids across New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, from Bathurst to Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine founded by B. C. Forbes in 1917. It has been owned by the Hong Kong–based investment group Integrated Whale Media Investments since 2014. Its chairman and editor-in-chief is Steve Forbes. The co ...

, south to Gundagai

Gundagai is a town in New South Wales, Australia. Although a small town, Gundagai is a popular topic for writers and has become a representative icon of a typical Australian country town. Located along the Murrumbidgee River and Muniong, Honeys ...

and east to Goulburn

Goulburn ( ) is a regional city in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, approximately south-west of Sydney and north-east of Canberra. It was proclaimed as Australia's first inland city through letters patent by Queen Victor ...

. Unlike many bushrangers of the era, Hall was not directly responsible for any deaths, although several of his associates were. He was shot dead by police in May 1865 at Goobang Creek. The police claimed that they were acting under the protection of the ''Felons Apprehension Act 1865'' which allowed any bushranger who had been specifically named under the terms of the Act to be shot and killed by any person at any time without warning. At the time of Hall's death, the Act had not yet come into force, resulting in considerable controversy over the legality of his killing."Family seeks justice for Bold Ben's demise", – Meacham, Steve, ''

The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria (Australia), Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Austral ...

'', 31 March 2007 Hall is a prominent figure in Australian folklore, inspiring many bush ballad

The bush ballad, bush song, or bush poem is a style of poetry and folk music that depicts the life, character and scenery of the Australian bush. The typical bush ballad employs a straightforward rhyme structure to narrate a story, often one of ...

s, books and screen works, including the 1975 television series '' Ben Hall'' and the 2016 feature film ''The Legend of Ben Hall

''The Legend of Ben Hall'' is a 2016 Australian bushranger film. Written and directed by Matthew Holmes, it is based on the exploits of bushranger Ben Hall and his gang. The film stars Jack Martin in the title role, Jamie Coffa as John Gilb ...

''.

*Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician and lawyer who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until Disappearance of Harold Holt, his disappearance and presumed death in 1967. He held o ...

– a prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

who disappeared while swimming in 1967. Conspiracy theories include Holt being picked up by a Chinese submarine, faking his own death, suicide, and CIA involvement. Formal investigations determined that he drowned accidentally. The expression "Like leaving the (porch) light on for Harold Holt" means to have a misplaced hope for an event to happen when the reality is that the event (Holt's having actually survived and being discovered still alive) is never likely to ever happen.

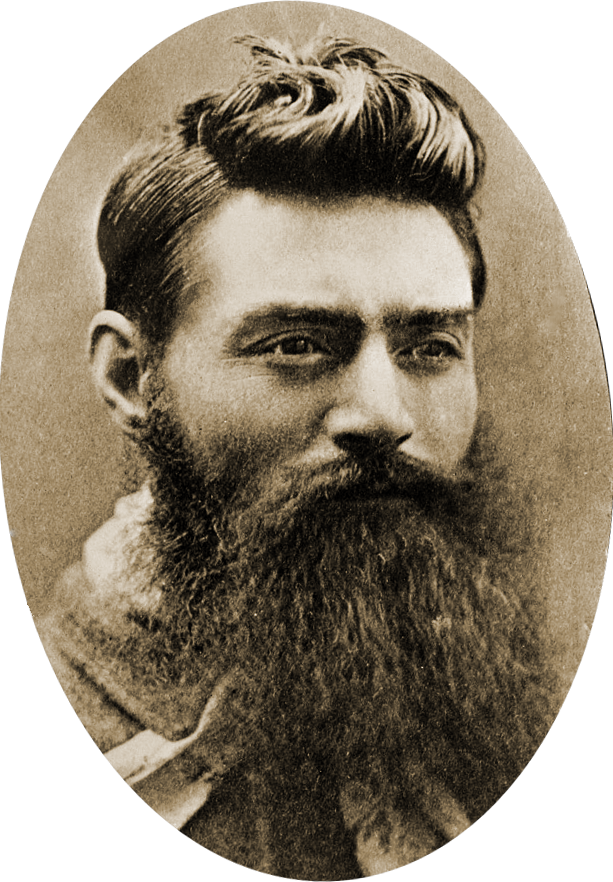

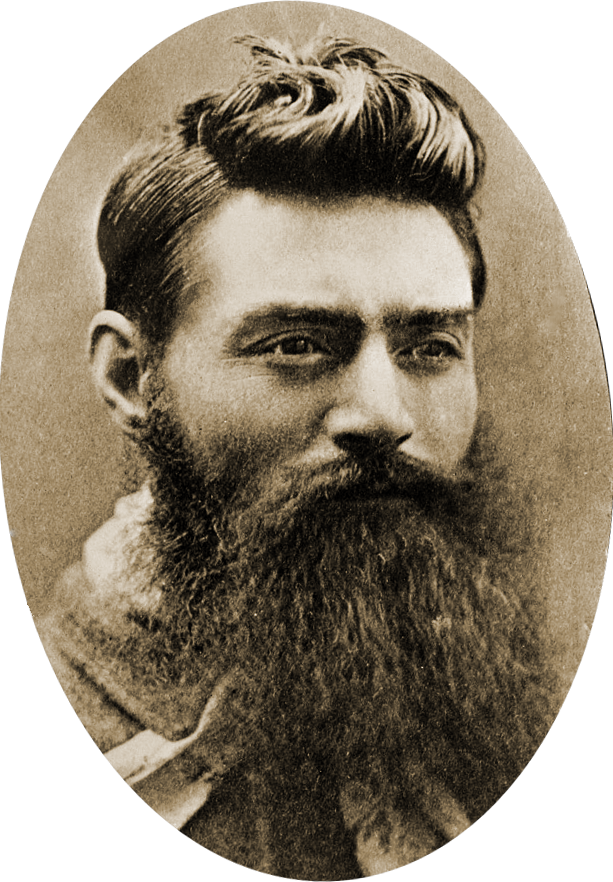

*Ned Kelly

Edward Kelly (December 185411 November 1880) was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader, bank robber and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing armour of the Kelly gang, a suit of bulletproof ...

– Australian 19th-century bushranger

Bushrangers were armed robbers and outlaws who resided in The bush#Australia, the Australian bush between the 1780s and the early 20th century. The original use of the term dates back to the early years of the British colonisation of Australia ...

, many films, books and artworks have been made about him, possibly his exploits have been exaggerated in the public eye and become something of folklore. It especially surrounds his capture at Glenrowan where the Kelly gang tried to derail a train of Victorian police which were arriving, and were surrounded in the hotel. Kelly had made armour from stolen iron mould boards of ploughs, and came out shooting, whereupon he was shot in the legs. Some consider him as Australia's Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary noble outlaw, heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature, theatre, and cinema. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions o ...

whiles others would disagree.

*

*Peter Lalor

Peter Fintan Lalor ( ); 5 February 1827 – 9 February 1889) was an Irish-Australian rebel and, later, politician, who rose to fame for his leading role in the Eureka Rebellion, an event identified with the "birth of democracy" in Austra ...

– an Irish-Australian rebel in the Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Rebellion was a series of events involving gold miners who revolted against the British administration of the colony of Victoria, Australia, during the Victorian gold rush. It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, wh ...

who later became the only outlaw to make it to parliament.

*Wally Lewis

Walter James Lewis AM (born 1 December 1959) is an Australian former professional rugby league footballer who played in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and coached in the 1980s and 1990s. He became a commentator for television coverage of the sp ...

– legendary rugby league player, captained the Queensland rugby league team in The State of Origin series

The State of Origin series is an annual best-of-three rugby league series between two States and territories of Australia, Australian state representative sides, the New South Wales rugby league team, New South Wales Blues and the Queensland ru ...

a record 30 times.

* Eddie Mabo – challenged the Australian Government as to who owned the island of Mer where he was born and lived. He believed the land belonged to the Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait Islands. He challenged the first court case to win in the High Court on 3 June 1992 – but sadly did not live to see his victory.

*Mary MacKillop

Mary Helen MacKillop RSJ ( in religion Mary of the Cross; 15 January 1842 – 8 August 1909) was an Australian religious sister. She was born in Melbourne but is best known for her activities in South Australia. Together with Fr Julian Teniso ...

– Australia's first saint, responsible for miracles such as curing a woman of leukemia after her family prayed for it.

*Dame Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic lyric coloratura soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early twentieth century, and was the f ...

– an Australian opera soprano

A soprano () is a type of classical singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types. The soprano's vocal range (using scientific pitch notation) is from approximately middle C (C4) = 261 Hertz, Hz to A5 in Choir, choral ...

, the first Australian to achieve international recognition in the form. The French dessert peach Melba is named after her. Many old theatre halls in regional Australia persist with rumours that she once graced their stage, most notably, that of the gold mining town of Gulgong, New South Wales. She is also remembered in the vernacular Australian expression "more comebacks than Nellie Melba", which satirised her seemingly endless series of "retirement" tours in the 1920s.

*Bert Newton

Albert Watson Newton (23 July 1938 – 30 October 2021) was an Australian media personality. He was a Logie Hall of Fame inductee, quadruple Gold Logie–winning entertainer, and radio, theatre and television personality and compère.

Ne ...

– looked upon as the most influential man in the history of Australian television.

*Pintupi Nine

The Pintupi Nine are a group of nine Pintupi people who remained unaware of European colonisation of Australia and lived a traditional desert-dwelling life in Australia's Gibson Desert until 1984, when they made contact with their relatives ne ...

– last indigenous Australian tribe who lived a traditional hunter-gatherer life in the Gibson Desert

The Gibson Desert is a large desert in Western Australia, largely in an almost pristine state. It is about in size, making it the fifth largest desert in Australia, after the Great Victoria, Great Sandy, Tanami and Simpson deserts. The ...

until they were discovered in 1984, almost 200 years since first colonization.

*Johnny O'Keefe

John Michael O'Keefe (19 January 1935 – 6 October 1978) was an Australian rock and roll singer whose career began in the early 1950s. A pioneer of Rock music in Australia, his hits include " Wild One" (1958), " Shout!" and "She's My Baby". O ...

– Australia's most successful chart performer, with twenty-nine Top 40 hits to his credit in Australia between 1959 and 1974.

*Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author, widely considered one of the greatest writers of Australia's colonial period.

Born in rural New South Wales, Paterson worke ...

– a bush poet

The bush ballad, bush song, or bush poem is a style of poetry and folk music that depicts the life, character and scenery of the Australian bush. The typical bush ballad employs a straightforward rhyme structure to narrate a story, often one of ...

who wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing mainly on the rural and outback areas of the country. Is widely considered Australia's greatest writer.

*Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy ( /pɛməlwɔɪ/ ''PEM-əl-woy''; 1750 – 2 June 1802) was a Bidjigal warrior of the Dharug, an Aboriginal Australian people from New South Wales. One of the most famous Aboriginal resistance fighters in the colonial era, he is n ...

– an Aboriginal rebel who fought against the British during the 18th and early 19th centuries, believed to have impossibly escaped from capture on countless occasions.

* Simpson and his Donkey – Soldier who is part of the ANZAC legend. During the Gallipoli Campaign at ANZAC Cove Simpson would help rescue Australian Soldiers and take them to safety.

* Squizzy Taylor – a petty criminal turned gangster from Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. He is believed to have constructed a series of tunnels throughout the inner suburbs of Fitzroy and Collingwood.

*White woman of Gippsland

The white woman of Gippsland, or the captive woman of Gippsland, was supposedly a European woman rumoured to have been held against her will by Aboriginal Gunaikurnai people in the Gippsland region of Australia in the 1840s. Her supposed plight e ...

– a European woman who was allegedly held captive by Aboriginals against her will in the 1840s, although her existence has been debated.

* Yagan – aboriginal warrior who fought against British settlement but was captured, in what is now Perth, Western Australia

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

.

* Cliff Young — potato farmer who won the 1981 Sydney-to-Melbourne ultramarathon at age 61 because he didn't realize the other runners would be stopping to sleep.

Places and structures

*Finke River

The Finke River, or Larapinta in the Indigenous Arrernte language, is a river in central Australia, whose bed courses through the Northern Territory and the state of South Australia. It is one of the four main rivers of Lake Eyre Basin and is th ...

– "Oldest river in the world", a claim that has been attributed to "scientists" by a generation of central Australian

Central Australia, also sometimes referred to as the Red Centre, is an inexactly defined region associated with the geographic centre of Australia. In its narrowest sense it describes a region that is limited to the town of Alice Springs and ...

bus drivers and tour brochure writers. Parts of the Finke River are likely the oldest major river known in the world or among the oldest, as shown in scientific literature, but this does not apply to the southern part of the river. Neighboring, smaller rivers are just as old.

* Franklin House – Historic house in Launceston that has had reports of ghost sightings.

*

* Franklin House – Historic house in Launceston that has had reports of ghost sightings.

*Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

– the name of a peninsula in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, but also the name given to the Allied campaign on that peninsula during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. There were around 180,000 Allied casualties and 220,000 Turkish casualties. This campaign has become a "founding myth

An origin myth is a type of myth that explains the beginnings of a natural or social aspect of the world. Creation myths are a type of origin myth narrating the formation of the universe. However, numerous cultures have stories that take place a ...

" for both Australia and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, and ANZAC Day

Anzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia, New Zealand and Tonga that broadly commemorates all Australians and New Zealanders "who served and died in all wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations" and "the contribution and ...

is still commemorated as a holiday in both countries. The idea that Australian soldiers were mowed down by Turkish gunfire following stupid decisions of the British commanding officers is part of the folklore, as is the escape from Gallipoli, where the ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was originally a First World War army corps of the British Empire under the command of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the ...

s used rifles rigged to fire by water dripped into a pan attached to the trigger to make it seem like there were still soldiers in the trenches as they were leaving. Another aspect of the ANZAC spirit is the story of Simpson and his donkey.

* Gentle Annie – Name for selected especially steep sections of bush roads, difficult to climb in wet weather. The folk term may have arisen as early as in bullock team days, whether drawing wagons or timber jinkers.

* Gympie Pyramid – A small pyramid like structure in Gympie

Gympie ( ) is a city and a Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Gympie Region, Queensland, Australia. Located in the Greater Sunshine Coast, Gympie is about north of the state capital, Brisbane. The city lies on the Mary River ( ...

, Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

(That has been mostly destroyed) that many believe to be a construction made by Chinese or Incan origin. Although researchers would more likely argue that it is a hoax

A hoax (plural: hoaxes) is a widely publicised falsehood created to deceive its audience with false and often astonishing information, with the either malicious or humorous intent of causing shock and interest in as many people as possible.

S ...

.

*Monte Cristo Homestead

Monte Cristo Homestead is a historic homestead located in the town of Junee, New South Wales, Australia. Constructed by local pioneer Christopher William Crawley in 1885, it is a double-storey late- Victorian-style manor standing on a hill ov ...

– Historic estate in Junee, New South Wales

Junee () is a medium-sized town in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. The town's prosperity and mixed services economy is based on a combination of agriculture, rail transport, light industry and government services, and in par ...

, said to be the most Haunted property in Australia.

*Parkes Observatory

Parkes Observatory is a radio astronomy observatory, located north of the town of Parkes, New South Wales, Australia. It hosts Murriyang, the 64 m CSIRO Parkes Radio Telescope also known as "The Dish", along with two smaller radio telescopes. T ...

– Landmark in New South Wales, responsible for helping NASA broadcast the Moon landing

A Moon landing or lunar landing is the arrival of a spacecraft on the surface of the Moon, including both crewed and robotic missions. The first human-made object to touch the Moon was Luna 2 in 1959.

In 1969 Apollo 11 was the first cr ...

s to the world.

*

*Pine Gap

Pine Gap is a joint Australian–United States satellite communications and signals intelligence surveillance base and Australian Earth station approximately south-west of the town of Alice Springs. It is jointly operated by Australia and ...

– A Government base in Central Australia run by both Australia and the United States. Similar to Area 51

Area 51 is the common name of a highly classified United States Air Force (USAF) facility within the Nevada Test and Training Range in southern Nevada, north-northwest of Las Vegas.

A remote detachment administered by Edwards Air Force B ...

.

*Port Arthur, Tasmania

Port Arthur is a town and former convict settlement on the Tasman Peninsula, in Tasmania, Australia. It is located approximately southeast of the state capital, Hobart.

The site forms part of the Australian Convict Sites, a World Heritag ...

– Former convict site, Has a complex and negative past, is said to haunted; But still a tourist attraction in Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, the site of Australia's biggest and most well known mass shootings, the Port Arthur Massacre (Australia)

The Port Arthur massacre was a mass shooting that occurred on 28 April 1996 at Port Arthur, a tourist town in the Australian state of Tasmania. The perpetrator, Martin Bryant, killed 35 people and wounded 23 others, the deadliest massacre i ...

.

* Princess Theatre Ghost sightings – One of the oldest theatres in Australia, it is said to be haunted after the death of Frederick Federici.

*Shrine of Remembrance

The Shrine of Remembrance (commonly referred to as The Shrine) is a war memorial in Melbourne, Victoria (state), Victoria, Australia, located in Kings Domain on St Kilda Road. It was built to honour the men and women of Victoria who served in ...

– War memorial in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

built to honour the men and women of Victoria who served in World War I but later dedicated to all Australians who gave their lives in war.

* Sydney–Melbourne rivalry – there has been a long-standing rivalry, usually friendly yet sometimes heated, between the cities of Melbourne and Sydney, the two largest cities in Australia. It was this very rivalry that ultimately acted as the catalyst for the eventual founding of Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

as the capital city of Australia.

*Snowy River

The Snowy River is a major river in south-eastern Australia. It originates on the slopes of Mount Kosciuszko, Australia's highest mainland peak, draining the eastern slopes of the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales, before flowing through the ...

– immortalised in another Banjo Paterson poem, " The Man from Snowy River". The river has received much attention of late for now being nothing more than a trickle, and in fact has become a symbol for wider Australian interest in the health of its great rivers, particularly those in the Murray-Darling basin.

*Sovereign Hill

Sovereign Hill is an open-air museum in Golden Point, a suburb of Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. Sovereign Hill depicts Ballarat's first ten years after the discovery of gold there in 1851 and has become a nationally acclaimed tourist attrac ...

– An Open-Air Museum

An open-air museum is a museum that exhibits collections of buildings and artifacts outdoors. It is also frequently known as a museum of buildings or a folk museum.

Definition

Open air is "the unconfined atmosphere ... outside buildings" ...

in Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

depicting an 1850s gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, ...

town.

* St James station tunnels – The tunnel is home to many urban legends including being a secret military bunker during World War II and a large bell that sounds like Big Ben

Big Ben is the nickname for the Great Bell of the Great Clock of Westminster, and, by extension, for the clock tower itself, which stands at the north end of the Palace of Westminster in London, England. Originally named the Clock Tower, it ...

.

*Sydney Harbour Bridge

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, spanning Port Jackson, Sydney Harbour from the Sydney central business district, central business district (CBD) to the North Shore (Sydney), North ...

& Sydney Opera House

The Sydney Opera House is a multi-venue Performing arts center, performing arts centre in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Located on the foreshore of Sydney Harbour, it is widely regarded as one of the world's most famous and distinctive b ...

– Two of Australia's most famous national landmarks. Know to people worldwide and cementing Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

as Australia's global city.

*The Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

– the only landmark in Australia (or Oceania) to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

*Uluru

Uluru (; ), also known as Ayers Rock ( ) and officially gazetted as UluruAyers Rock, is a large sandstone monolith. It outcrop, crops out near the centre of Australia in the southern part of the Northern Territory, south-west of Alice Spri ...

– Large sandstone rock formation in central Australia. Has great cultural significance to Aboriginal Australians and is one of Australia's most famous landmarks.

* Westall – biggest UFO sighting in Australian history, what actually was sighted remains a mystery to this day.

* Wiebbe Hayes Stone Fort – Oldest European building in Australia, built in 1629 by survivors of the Batavia shipwreck in which a mutiny took place.

Socio-political events

*Australian constitutional crisis of 1975

The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, also known simply as the Dismissal, culminated on 11 November 1975 with the dismissal from office of the prime minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), by Sir John Kerr, the govern ...

– a real political crisis that has since taken on mythic proportions and elevated the protagonists to legendary status (depending on which side of the debate one takes). A visiting American politician at the time wryly observed that he was sure he had only heard the tip of the ice cube. Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from December 1972 to November 1975. To date the longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), he was notable for being ...

's speech "Well may we say God save the Queen

"God Save the King" ("God Save the Queen" when the monarch is female) is '' de facto'' the national anthem of the United Kingdom. It is one of two national anthems of New Zealand and the royal anthem of the Isle of Man, Australia, Canada and ...

, because nothing will save the Governor General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

" is replayed frequently.

*

* Eureka stockade

The Eureka Rebellion was a series of events involving gold miners who revolted against the British administration of the colony of Victoria, Australia, during the Victorian gold rush. It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, wh ...

– A miners' revolt in 1854 in Victoria, Australia against the officials supervising the gold-mining region of Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) () is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 census, Ballarat had a population of 111,973, making it the third-largest urban inland city in Australia and the third-largest city in Victoria.

Within mo ...

, in particular, the high prices of digging licenses. It is often regarded as the "Birth of Australian Democracy" and an event of equal significance to Australian history

The history of Australia is the history of the land and peoples which comprise the Commonwealth of Australia. The modern nation came into existence on 1 January 1901 as a federation of former British colonies. The human history of Australia, ...

as the storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille ( ), which occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, was an act of political violence by revolutionary insurgents who attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison k ...

was to French history

The first written records for the history of France appeared in the Iron Age.

What is now France made up the bulk of the region known to the Romans as Gaul. Greek writers noted the presence of three main ethno-linguistic groups in the area: t ...

, but almost equally often dismissed as being of little or no consequence.

* The Stolen Generation – From the late 1800s to the early 1970s, young Aboriginal people were forcibly removed from their families as children between the 1900s and the 1960s, to be brought up by white foster families or in institutions. In 1999 then-prime minister John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

avoided using the word "sorry", to the families. In 2008 Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

made an official apology to the stolen generation and their families, on behalf of the Australian government.

* Tenterfield Oration

The Tenterfield Oration was a speech delivered by Sir Henry Parkes, Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, at the Tenterfield School of Arts in Tenterfield, New South Wales, Australia, on 24 October 1889.

In the oration, Parkes called for ...

– Speech given by Sir Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and the longest-serving non-consecutive premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australi ...

in 1889 calling for the six Australian colonies to be Federated, which would eventually lead to the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and numerous smaller islands. It has a total area of , making it the sixth-largest country in ...

.

Sport

*2000 Sydney Olympics

The 2000 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the XXVII Olympiad, officially branded as Sydney 2000, and also known as the Games of the New Millennium, were an international multi-sport event held from 15 September to 1 October ...

– Hailed as one of the greatest Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

of all time, It captured the imagination of an entire country and gave birth to many Australian sporting moments and icons, including Cathy Freeman, Grant Hackett

Grant George Hackett Order of Australia, OAM (born 9 May 1980) is an Australian swimmer, most famous for winning the men's 1500 metres freestyle swimming, freestyle race at both the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney and the 2004 Summer Olympics in ...

, Susie O'Neill

Susan O'Neill, (born 2 August 1973) is an Australian former competitive swimmer from Brisbane, Queensland, nicknamed "Madame Butterfly". She achieved eight Olympic Games medals during her swimming career.

Early life

O'Neill was born on 2 Augu ...

, and Ian Thorpe

Ian James Thorpe (born 13 October 1982) is an Australian retired swimmer who specialised in freestyle swimming, freestyle, but also competed in backstroke and the medley swimming, individual medley. He has won five Olympic gold medals, the se ...

.

*''Australia II

''Australia II'' (KA 6) is an Australian 12-metre-class America's Cup challenge racing yacht that was launched in 1982 and won the 1983 America's Cup for the Royal Perth Yacht Club. Skippered by John Bertrand, she was the first successf ...

'' – A 12-metre class

The 12 Metre class is a rating class for racing sailboats that are designed to the International rule. It enables fair competition between boats that rate in the class whilst retaining the freedom to experiment with the details of their designs. ...

yacht

A yacht () is a sail- or marine propulsion, motor-propelled watercraft made for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a ...

that was the first successful challenger for the America's Cup

The America's Cup is a sailing competition and the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one from the yacht club that currently holds the trophy (known ...

after 132 years. On the morning of the victory (Australian time) the then Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991. He held office as the Australian Labor Party, leader of the La ...

, famously said that any employer who sacked any of their employees for not coming in that day was a "bum". The challenge also resulted in the popularisation of the boxing kangaroo representation.

*

*Colliwobbles

In the Australian Football League (AFL), the "Colliwobbles" refers to the period between Collingwood's 1958 and 1990 premierships, where the Magpies reached nine AFL/VFL Grand Finals for eight losses and a draw in 1977.

This era was dubbed as ...

– The "Colliwobbles" refers to the Collingwood Football Club's apparent penchant for losing grand finals over a 32-year period between 1958 and 1990. During this premiership drought, fans endured nine fruitless grand finals (1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

, 1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

, 1966

Events January

* January 1 – In a coup, Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa takes over as military ruler of the Central African Republic, ousting President David Dacko.

* January 3 – 1966 Upper Voltan coup d'état: President Maurice Yaméogo i ...

, 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 1970 Tonghai earthquake, Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity scale, Mercalli ...

, 1977

Events January

* January 8 – 1977 Moscow bombings, Three bombs explode in Moscow within 37 minutes, killing seven. The bombings are attributed to an Armenian separatist group.

* January 10 – Mount Nyiragongo erupts in eastern Zaire (no ...

(drawn, then lost in a replay the following week), 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the ''International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the ''Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the song ...

, 1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a United States grain embargo against the Soviet Union, grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning Sys ...

, 1981

Events January

* January 1

** Greece enters the European Economic Community, predecessor of the European Union.

** Palau becomes a self-governing territory.

* January 6 – A funeral service is held in West Germany for Nazi Grand Admiral ...

). The term "Colliwobbles" was to enter the Victorian vocabulary to signify a choking phenomenon.

* The Invincibles – First Test match side to play an entire tour of England without losing, and is often considered to be one of the greatest cricket teams of all time.

* Kennett curse – A 5-year winning streak Geelong

Geelong ( ) (Wathawurrung language, Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in Victoria, Australia, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon River (Victo ...

had over Hawthorn over comments made by then Hawthorn club President Jeff Kennett

Jeffrey Gibb Kennett (born 2 March 1948) is an Australian former politician who served as the 43rd Premier of Victoria between 1992 and 1999, Leader of the Victorian Liberal Party from 1982 to 1989 and from 1991 to 1999, and the Member for ...

saying that Geelong does not have the mental drive to defeat Hawthorn. Most games were decided by ten points or less and are considered some of the best in recent memory.

*Phar Lap

Phar Lap (4 October 1926 – 5 April 1932) was a New Zealand-born champion Australian Thoroughbred horse racing, racehorse. Achieving great success during his distinguished career, his initial underdog status gave people hope during the ear ...

– A thoroughbred

The Thoroughbred is a list of horse breeds, horse breed developed for Thoroughbred racing, horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thorough ...

horse who is considered by many to be the world's greatest racehorse

Horse racing is an equestrian performance activity, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its bas ...

, and is probably subject to more conspiracy theories than any other racehorse (in relation to the cause of his death). His name entered the Australian lexicon in the expression "to have a heart bigger than Phar Lap's", referring to someone's tenacity and courage. It is part of Australian folklore that Phar Lap's heart was physically twice the size of the average horse's heart.

*Super League war

The Super League war was a commercial competition between the Australian Rugby League (ARL) and the Australian Super League to establish pre-eminence in professional rugby league competition in Australia and New Zealand in the mid-1990s.

Sup ...

– A dispute between the Packer and Murdoch

Murdoch ( , ) Is a Scottish and Irish surname and given name. An Anglicized form of the Gaelic personal names ''Muireadhach'' ‘mariner’, ''Murchadh'' ‘sea-warrior’, and ''Muirchertach, Muircheartach'' ‘sea-ruler’, the first element i ...

families over control of the top-level Rugby League

Rugby league football, commonly known as rugby league in English-speaking countries and rugby 13/XIII in non-Anglophone Europe, is a contact sport, full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular Rugby league playin ...

competition in Australia in the mid-1990s.

* Steven Bradbury – An Australian short-track speed skater who memorably won gold at the 2002 Winter Olympics

The 2002 Winter Olympics, officially the XIX Olympic Winter Games and commonly known as Salt Lake 2002 (; Gosiute dialect, Gosiute Shoshoni: ''Tit'-so-pi 2002''; ; Shoshoni language, Shoshoni: ''Soónkahni 2002''), were an international wi ...

at the 1,000 m short track, going from last to first after all other skaters were involved in a pile-up during the final metres. This led to the phrase 'doing a Bradbury', meaning to achieve something with the odds stacked against you.

Other

* 5 o'clock wave – Supposedly a large wave, several metres in height and created by the daily release of dam overflow, that is said to travel downriver at high speed, and to reach the location at which the tale is being told at 5 o'clock each afternoon.

* ANZAC spirit – Idea shared by Australian &

* 5 o'clock wave – Supposedly a large wave, several metres in height and created by the daily release of dam overflow, that is said to travel downriver at high speed, and to reach the location at which the tale is being told at 5 o'clock each afternoon.

* ANZAC spirit – Idea shared by Australian & New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

soldiers during WW1 which has contributed to the "National Character" of both countries, and embodies the cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

idiom

An idiom is a phrase or expression that largely or exclusively carries a Literal and figurative language, figurative or non-literal meaning (linguistic), meaning, rather than making any literal sense. Categorized as formulaic speech, formulaic ...

of Mateship

Mateship is an Australian cultural idiom that embodies equality, loyalty and friendship. Russel Ward, in ''The Australian Legend'' (1958), once saw the concept as central to the Australian people. ''Mateship'' derives from '' mate'', meaning ''f ...

.

* Akubra – Wide-brimmed hat made famous by outlaws and soldiers.

* Big Things – Many Australian towns are known for their large and sometimes unusual structures or sculptures.

* Bass Strait Triangle – Similar to the Bermuda Triangle

The Bermuda Triangle, also known as the Devil's Triangle, is a loosely defined region in the North Atlantic Ocean, roughly bounded by Florida, Bermuda, and Puerto Rico. Since the mid-20th century, it has been the focus of an urban legend sug ...

, the Bass Strait Triangle which lies between the states of Victoria and Tasmania