Archaeopteryxes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird'') is a

The initial discovery, a single feather, was unearthed in 1860 or 1861 and described in 1861 by . It is now in the Natural History Museum of Berlin. Though it was the initial

The initial discovery, a single feather, was unearthed in 1860 or 1861 and described in 1861 by . It is now in the Natural History Museum of Berlin. Though it was the initial  Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the

Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the  The discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced in 2011; it was described in 2014. It is one of the more complete specimens, but is missing much of the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name. Palaeontologists of the

The discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced in 2011; it was described in 2014. It is one of the more complete specimens, but is missing much of the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name. Palaeontologists of the

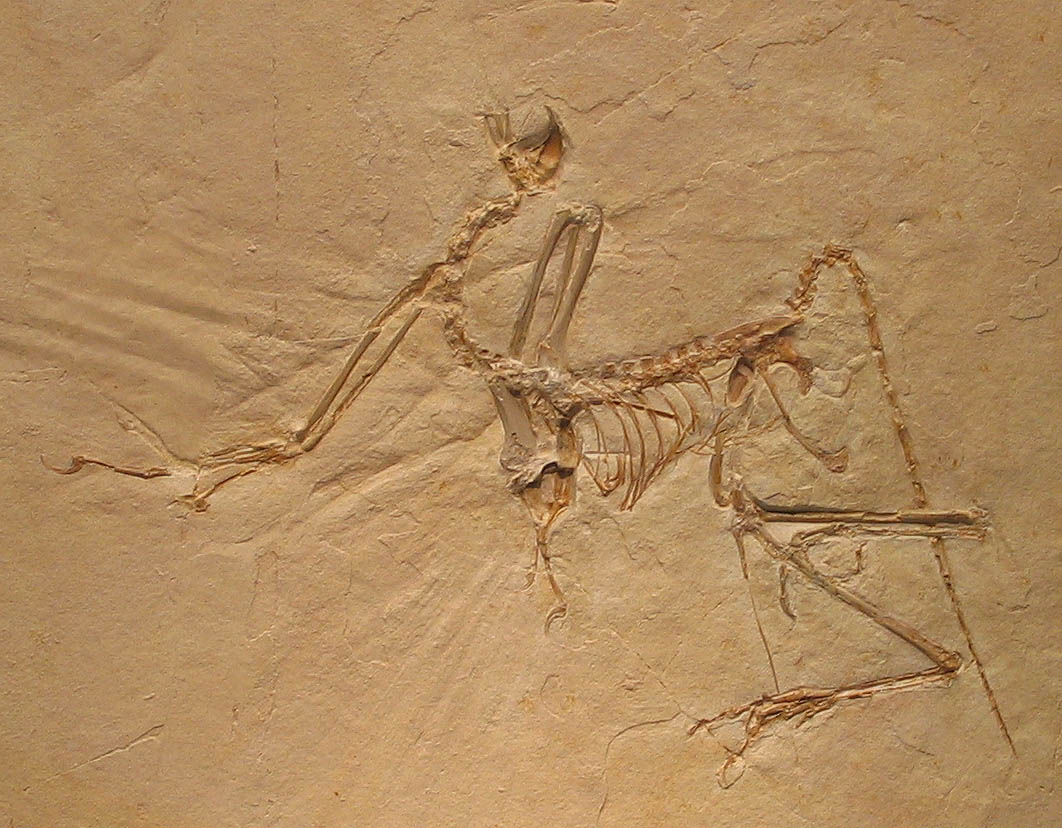

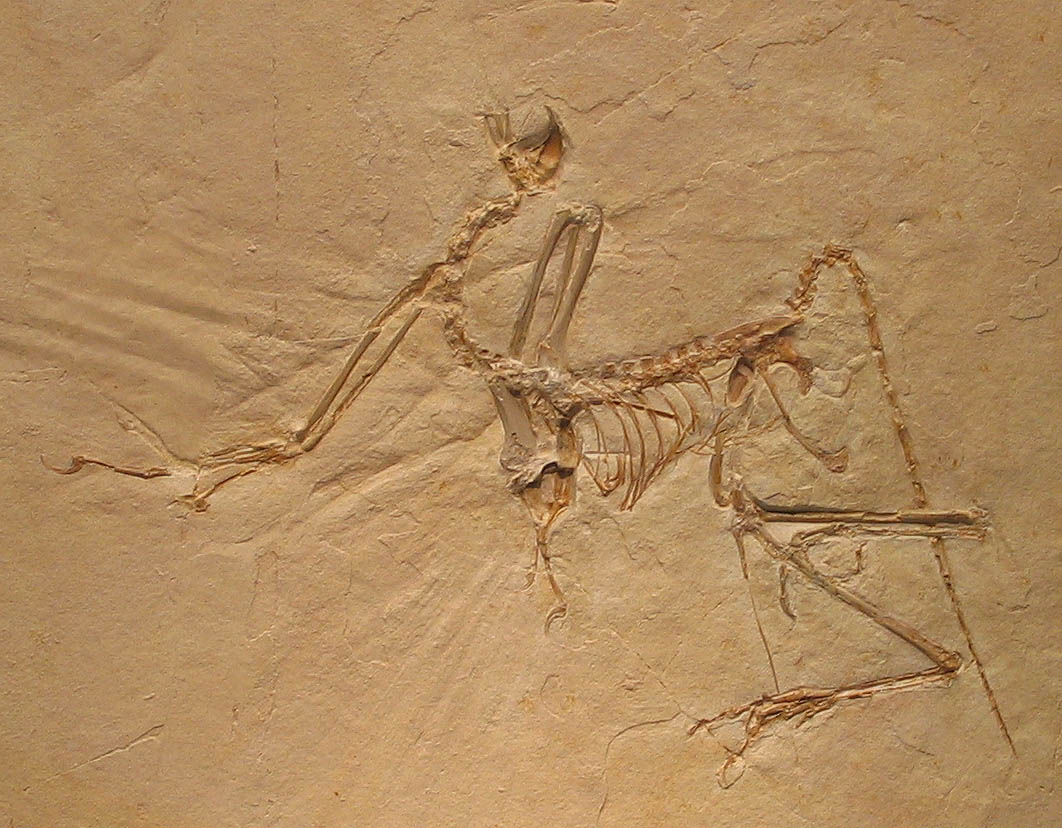

Most of the specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' that have been discovered come from the Solnhofen limestone in Bavaria, southern Germany, which is a , a rare and remarkable geological formation known for its superbly detailed fossils laid down during the early Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 150.8–148.5million years ago.

''Archaeopteryx'' was roughly the size of a

Most of the specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' that have been discovered come from the Solnhofen limestone in Bavaria, southern Germany, which is a , a rare and remarkable geological formation known for its superbly detailed fossils laid down during the early Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 150.8–148.5million years ago.

''Archaeopteryx'' was roughly the size of a

Specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' were most notable for their well-developed

Specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' were most notable for their well-developed

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen. Using

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen. Using

Today, fossils of the genus ''Archaeopteryx'' are usually assigned to one or two species, ''A. lithographica'' and ''A. siemensii'', but their taxonomic history is complicated. Ten names have been published for the handful of specimens. As interpreted today, the name ''A. lithographica'' only referred to the single feather described by

Today, fossils of the genus ''Archaeopteryx'' are usually assigned to one or two species, ''A. lithographica'' and ''A. siemensii'', but their taxonomic history is complicated. Ten names have been published for the handful of specimens. As interpreted today, the name ''A. lithographica'' only referred to the single feather described by  Below is a

Below is a

It has been argued that all the specimens belong to the same species, ''A. lithographica''. Differences do exist among the specimens, and while some researchers regard these as due to the different ages of the specimens, some may be related to actual species diversity. In particular, the Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis specimens differ from the London, Berlin, and Haarlem specimens in being smaller or much larger, having different finger proportions, having more slender snouts lined with forward-pointing teeth, and the possible presence of a

It has been argued that all the specimens belong to the same species, ''A. lithographica''. Differences do exist among the specimens, and while some researchers regard these as due to the different ages of the specimens, some may be related to actual species diversity. In particular, the Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis specimens differ from the London, Berlin, and Haarlem specimens in being smaller or much larger, having different finger proportions, having more slender snouts lined with forward-pointing teeth, and the possible presence of a

Modern palaeontology has often classified ''Archaeopteryx'' as the most primitive bird. However, it is not thought to be a true ancestor of modern birds, but rather a close relative of that ancestor. Nonetheless, ''Archaeopteryx'' was often used as a model of the true ancestral bird. Several authors have done so. Lowe (1935) and Thulborn (1984) questioned whether ''Archaeopteryx'' truly was the first bird. They suggested that ''Archaeopteryx'' was a dinosaur that was no more closely related to birds than were other dinosaur groups. Kurzanov (1987) suggested that ''

Modern palaeontology has often classified ''Archaeopteryx'' as the most primitive bird. However, it is not thought to be a true ancestor of modern birds, but rather a close relative of that ancestor. Nonetheless, ''Archaeopteryx'' was often used as a model of the true ancestral bird. Several authors have done so. Lowe (1935) and Thulborn (1984) questioned whether ''Archaeopteryx'' truly was the first bird. They suggested that ''Archaeopteryx'' was a dinosaur that was no more closely related to birds than were other dinosaur groups. Kurzanov (1987) suggested that ''

As in the wings of modern birds, the flight feathers of ''Archaeopteryx'' were somewhat asymmetrical and the tail feathers were rather broad. This implies that the wings and tail were used for lift generation, but it is unclear whether ''Archaeopteryx'' was capable of flapping flight or simply a glider. The lack of a bony

As in the wings of modern birds, the flight feathers of ''Archaeopteryx'' were somewhat asymmetrical and the tail feathers were rather broad. This implies that the wings and tail were used for lift generation, but it is unclear whether ''Archaeopteryx'' was capable of flapping flight or simply a glider. The lack of a bony  In 2010, Robert L. Nudds and Gareth J. Dyke in the journal ''Science'' published a paper in which they analysed the

In 2010, Robert L. Nudds and Gareth J. Dyke in the journal ''Science'' published a paper in which they analysed the

"Did First Feathers Prevent Early Flight?"

''Science Now'', 13 May 2010. ''Archaeopteryx'' continues to play an important part in scientific debates about the origin and evolution of birds. Some scientists see it as a semi-arboreal climbing animal, following the idea that birds evolved from tree-dwelling gliders (the "trees down" hypothesis for the evolution of flight proposed by

''Archaeopteryx'' continues to play an important part in scientific debates about the origin and evolution of birds. Some scientists see it as a semi-arboreal climbing animal, following the idea that birds evolved from tree-dwelling gliders (the "trees down" hypothesis for the evolution of flight proposed by

An

An

The richness and diversity of the

The richness and diversity of the

* P. Shipman (1998). ''Taking Wing: Archaeopteryx and the Evolution of Bird Flight''. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London. . * P. Wellnhofer (2008). ''Archaeopteryx – Der Urvogel von Solnhofen'' (in German). Verlag Friedrich Pfeil, Munich. .

from

Use of SSRL X-ray takes 'transformative glimpse'

– A look at chemicals linking birds and dinosaurs

– University of California Museum of Paleontology

– University of California Museum of Paleontology {{Authority control Archaeopterygidae Dinosaur genera Tithonian dinosaurs Dinosaurs of Germany Fossil taxa described in 1861 Taxa named by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer Feathered dinosaurs

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

-like dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s. The name derives from the ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(''archaîos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" or "wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, ''Archaeopteryx'' was generally accepted by palaeontologists

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

and popular reference books as the oldest known bird (member of the group Avialae

Avialae ("bird wings") is a clade containing the only living dinosaurs, the birds, and their closest relatives. It is usually defined as all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds (Aves) than to Deinonychosauria, deinonychosaurs, though ...

). Older potential avialan

Avialae ("bird wings") is a clade containing the only living dinosaurs, the birds, and their closest relatives. It is usually defined as all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds (Aves) than to deinonychosaurs, though alternative defi ...

s have since been identified, including ''Anchiornis

''Anchiornis'' is a genus of small, four-winged Paraves, paravian dinosaurs, with only one known species, the type species ''Anchiornis huxleyi'', named for its similarity to modern birds. The Latin name ''Anchiornis'' derives from a Greek word m ...

'', ''Xiaotingia

''Xiaotingia'' is a genus of Paraves, paravian theropod dinosaur, possibly an Anchiornithidae, anchiornithid, from Middle Jurassic or early Late Jurassic deposits of western Liaoning, China. It contains a single species, ''Xiaotingia zhengi''.

D ...

'', ''Aurornis

''Aurornis'' is an extinct genus of anchiornithid theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic period of China. The genus ''Aurornis'' contains a single known species, ''Aurornis xui'' (). ''Aurornis xui'' may be the most basal ("primitive") avialan di ...

'', and ''Baminornis

''Baminornis'' (meaning "Fujian Province bird") is an extinct genus of basal avialans from the Late Jurassic (Tithonian age) Nanyuan Formation of China. The genus contains a single species, ''B. zhenghensis'', known from a partial skeleton. ' ...

''.

''Archaeopteryx'' lived in the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time scale, geologic time from 161.5 ± 1.0 to 143.1 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic stratum, strata.Owen ...

around 150 million years ago, in what is now southern Germany, during a time when Europe was an archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

of islands in a shallow warm tropical sea, much closer to the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

than it is now. Similar in size to a Eurasian magpie

The Eurasian magpie or common magpie (''Pica pica'') is a resident breeding bird throughout the northern part of the Eurasian continent. It is one of several birds in the crow family (corvids) designated magpies, and belongs to the Holarctic r ...

, with the largest individuals possibly attaining the size of a raven

A raven is any of several large-bodied passerine bird species in the genus '' Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between crows and ravens; the two names are assigne ...

, the largest species of ''Archaeopteryx'' could grow to about in length. Despite their small size, broad wings, and inferred ability to fly or glide, ''Archaeopteryx'' had more in common with other small Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

dinosaurs than with modern birds. In particular, they shared the following features with the dromaeosaurids

Dromaeosauridae () is a family of feathered coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous Period. The name Dromaeosauridae means 'running lizards', from Gree ...

and troodontids

Troodontidae is a clade of bird-like theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous. During most of the 20th century, troodontid fossils were few and incomplete and they have therefore been allied, at various times, with many dinos ...

: jaws with sharp teeth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

, three fingers with claw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or Arthro ...

s, a long bony tail, hyperextensible second toes ("killing claw"), feathers (which also suggest warm-bloodedness

Warm-blooded is a term referring to animal species whose bodies maintain a temperature higher than that of their environment. In particular, homeothermic species (including birds and mammals) maintain a stable body temperature by regulating m ...

), and various features of the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

.

These features make ''Archaeopteryx'' a clear candidate for a transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross ...

between non-avian dinosaurs and avian dinosaurs (birds). Thus, ''Archaeopteryx'' plays an important role, not only in the study of the origin of birds

The scientific question of which larger group of animals birds evolved within has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated du ...

, but in the study of dinosaurs. It was named from a single feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an exa ...

in 1861, the identity of which has been controversial. That same year, the first complete specimen of ''Archaeopteryx'' was announced. Over the years, twelve more fossils of ''Archaeopteryx'' have surfaced. Despite variation among these fossils, most experts regard all the remains that have been discovered as belonging to a single species or at least genus, although this is still debated.

Most of these 14 fossils include impressions of feathers. Because these feathers are of an advanced form (flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

s), these fossils are evidence that the evolution of feathers began before the Late Jurassic. The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

of ''Archaeopteryx'' was discovered just two years after Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

published ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. ''Archaeopteryx'' seemed to confirm Darwin's theories and has since become a key piece of evidence for the origin of birds, the transitional fossils debate, and confirmation of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. ''Archaeopteryx'' was long considered to be the beginning of the evolutionary tree of birds. However, in recent years, the discovery of several small, feathered dinosaurs has created a mystery for palaeontologists, raising questions about which animals are the ancestors of modern birds and which are their relatives.

History of discovery

Over the years, fourteen body fossil specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' have been found. All of the fossils come from thelimestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

deposits, quarried for centuries, near , Germany. These quarries excavate sediments from the Solnhofen Limestone

The Solnhofen Limestone or Solnhofen Plattenkalk, formally known as the Altmühltal Formation, is a Jurassic Konservat-Lagerstätte that preserves a rare assemblage of fossilized organisms, including highly detailed imprints of soft bodied organi ...

formation and related units. The initial specimen was the first dinosaur to be discovered with feathers.

holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

, there were indications that it might not have been from the same animal as the body fossils. In 2019 it was reported that laser imaging had revealed the structure of the quill (which had not been visible since some time after the feather was described), and that the feather was inconsistent with the morphology of all other ''Archaeopteryx'' feathers known, leading to the conclusion that it originated from another dinosaur. This conclusion was challenged in 2020 as being unlikely; the feather was identified on the basis of morphology as most likely having been an upper major primary covert feather

A covert feather or tectrix on a bird is one of a set of feathers, called coverts (or ''tectrices''), which cover other feathers. The coverts help to smooth airflow over the wings and tail.

Ear coverts

The ear coverts are small feathers behind t ...

.

The first skeleton, known as the London Specimen (BMNH 37001), was unearthed in 1861 near , Germany, and perhaps given to local physician in return for medical services. He then sold it for £700 (roughly £83,000 in 2020) to the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London, where it remains. Missing most of its head and neck, it was described in 1863 by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

as ''Archaeopteryx macrura'', allowing for the possibility it did not belong to the same species as the feather. In the subsequent fourth edition of his ''On the Origin of Species'', Charles Darwin described how some authors had maintained "that the whole class of birds came suddenly into existence during the eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

period; but now we know, on the authority of Professor Owen, that a bird certainly lived during the deposition of the upper greensand; and still more recently, that strange bird, the ''Archaeopteryx'', with a long lizard-like tail, bearing a pair of feathers on each joint, and with its wings furnished with two free claws, has been discovered in the oolitic slates of Solnhofen. Hardly any recent discovery shows more forcibly than this how little we as yet know of the former inhabitants of the world."

The Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

word () means 'ancient, primeval'. primarily means 'wing', but it can also be just 'feather'. Meyer suggested this in his description. At first he referred to a single feather which appeared to resemble a modern bird's remex (wing feather), but he had heard of and been shown a rough sketch of the London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

specimen, to which he referred as a "" ("skeleton of an animal covered in similar feathers"). In German, this ambiguity is resolved by the term which does not necessarily mean a wing used for flying. was the favoured translation of ''Archaeopteryx'' among German scholars in the late nineteenth century. In English, 'ancient pinion' offers a rough approximation to this.

Since then, twelve specimens have been recovered:

The Berlin Specimen (HMN 1880/81) was discovered in 1874 or 1875 on the Blumenberg near , Germany, by farmer Jakob Niemeyer. He sold this precious fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

for the money to buy a cow in 1876, to innkeeper Johann Dörr, who again sold it to Ernst Otto Häberlein, the son of K. Häberlein. Placed on sale between 1877 and 1881, with potential buyers including O. C. Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

of Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

's Peabody Museum, it eventually was bought for 20,000 Goldmark by the Berlin's Natural History Museum, where it now is displayed. The transaction was financed by Ernst Werner von Siemens

Ernst Werner Siemens (von Siemens from 1888; ; ; 13 December 1816 – 6 December 1892) was a German electrical engineer, inventor and industrialist. Siemens's name has been adopted as the SI unit of electrical conductance, the siemens. He fou ...

, founder of the company that bears his name. Described in 1884 by Wilhelm Dames

Wilhelm Barnim Dames (9 June 1843, in Stolp – 22 December 1898, in Berlin) was a German paleontologist of the Berlin University, who described the first complete specimen of the early bird ''Archaeopteryx'' in 1894. This specimen is currently in ...

, it is the most complete specimen, and the first with a complete head. In 1897 it was named by Dames as a new species, ''A. siemensii''; though often considered a synonym of ''A. lithographica'', several 21st century studies have concluded that it is a distinct species which includes the Berlin, Munich, and Thermopolis specimens.

Composed of a torso, the Maxberg Specimen (S5) was discovered in 1956 near Langenaltheim; it was brought to the attention of professor Florian Heller

Florian Heller (born 10 March 1982 in Rosenheim) is a German football coach and former footballer. He is currently the manager of SpVgg Unterhaching U17.

He made his debut on the professional league level in the 2. Bundesliga for SpVgg Greuth ...

in 1958 and described by him in 1959. The specimen is missing its head and tail, although the rest of the skeleton is mostly intact. Although it was once exhibited at the Maxberg Museum in Solnhofen

Solnhofen is a municipality in the district of Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen in the region of Middle Franconia in the ' of Bavaria in Germany. It is in the Altmühl valley.

The local area is famous in geology and palaeontology for Solnhofen lime ...

, it is currently missing. It belonged to Eduard Opitsch, who loaned it to the museum until 1974. After his death in 1991, it was discovered that the specimen was missing and may have been stolen or sold.

The Haarlem Specimen (TM 6428/29, also known as the ''Teylers Specimen'') was discovered in 1855 near , Germany, and described as a ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from ) is a genus of extinct pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying reptile and one of the first prehis ...

crassipes'' in 1857 by Meyer. It was reclassified in 1970 by John Ostrom

John Harold Ostrom (February 18, 1928 – July 16, 2005) was an American paleontologist who revolutionized the modern understanding of dinosaurs. Ostrom's work inspired what his pupil Robert T. Bakker has termed a " dinosaur renaissance".

Begin ...

and is currently located at the Teylers Museum

Teylers Museum () is an Art museum, art, Natural history museum, natural history, and science museum in Haarlem, Netherlands. Established in 1778, Teylers Museum was founded as a centre for contemporary art and science. The historic centre of the ...

in Haarlem

Haarlem (; predecessor of ''Harlem'' in English language, English) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands. It is the capital of the Provinces of the Nether ...

, the Netherlands. It was the very first specimen found, but was incorrectly classified at the time. It is also one of the least complete specimens, consisting mostly of limb bones, isolated cervical vertebrae, and ribs. In 2017 it was named as a separate genus ''Ostromia

''Ostromia crassipes'' (''Thick-foot of John Ostrom'') is the single species of the anchiornithid theropod dinosaur genus ''Ostromia''. Recovered from the Late Jurassic Painten Formation of Germany, it was named by Christian Foth and Oliver Rau ...

'', considered more closely related to ''Anchiornis

''Anchiornis'' is a genus of small, four-winged Paraves, paravian dinosaurs, with only one known species, the type species ''Anchiornis huxleyi'', named for its similarity to modern birds. The Latin name ''Anchiornis'' derives from a Greek word m ...

'' from China.

The Eichstätt Specimen (JM 2257) was discovered in 1951 near Workerszell

Workerszell is a village in the municipality of Schernfeld north of Eichstätt in Bavaria, Germany, stretching alongside the B 13 road, situated in the Franconian Jura

The Franconian Jura ( , , or ) is an upland in Franconia, Bavaria, Germany ...

, Germany, and described by Peter Wellnhofer

Peter Wellnhofer (born Munich, 1936) is a German paleontologist at the Bayerische Staatssammlung fur Paläontologie in Munich. He is best known for his work on the various fossil specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' or "Urvogel", the first known bird. ...

in 1974. Currently located at the Jura Museum

The Jura Museum, a museum located in Willibaldsburg castle in the town of Eichstätt, Germany, is a natural history museum that has an extensive exhibit of Jurassic fossils from the quarries of Solnhofen and surroundings, including marine rept ...

in Eichstätt, Germany, it is the smallest known specimen and has the second-best head. It is possibly a separate genus (''Jurapteryx recurva'') or species (''A. recurva'').

The Solnhofen Specimen (unnumbered specimen) was discovered in the 1970s near Eichstätt, Germany, and described in 1988 by Wellnhofer. Currently located at the Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum

The Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum is a natural history museum in Solnhofen, Germany. In 1954 the mayor, Friedrich Mueller, made his private collection accessible to the public. In 1968 the museum was officially founded by the Solnhofen municipali ...

in Solnhofen, it originally was classified as ''Compsognathus

''Compsognathus'' (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''kompsos''/κομψός; "elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and ''gnathos''/γνάθος; "jaw") is a genus of small, bipedalism, bipedal, carnivore, carnivorous theropoda, theropod dinosaur. Members o ...

'' by an amateur collector, the same mayor Friedrich Müller after which the museum is named. It is the largest specimen known and may belong to a separate genus and species, ''Wellnhoferia

''Wellnhoferia'' (named after Peter Wellnhofer) is a genus of early prehistoric bird-like theropod dinosaur closely related to ''Archaeopteryx''. It lived in what is now Germany, during the Late Jurassic. While ''Wellnhoferia'' was similar to '' ...

grandis''. It is missing only portions of the neck, tail, backbone, and head.

The Munich Specimen (BSP 1999 I 50, formerly known as the ''Solenhofer-Aktien-Verein Specimen'') was discovered on 3 August 1992 near Langenaltheim and described in 1993 by Wellnhofer. It is currently located at the Paläontologisches Museum München

The Palaeontological Museum in Germany (''Paläontologisches Museum München''), is a German national natural history museum located in the city of Munich, Bavaria. It is associated with the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. It has a large co ...

in Munich, to which it was sold in 1999 for 1.9 million Deutschmark

The Deutsche Mark (; "German mark"), abbreviated "DM" or "D-Mark" (), was the official currency of West Germany from 1948 until 1990 and later of unified Germany from 1990 until the adoption of the euro in 2002. In English, it was typically ca ...

. What was initially believed to be a bony sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

turned out to be part of the coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

, but a cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints ...

sternum may have been present. Only the front of its face is missing. It has been used as the basis for a distinct species, ''A. bavarica'', but more recent studies suggest it belongs to ''A. siemensii''.

An eighth, fragmentary specimen was discovered in 1990 in the younger Mörnsheim Formation

The Mörnsheim Formation is a geologic formation in Germany, near Daiting and Mörnsheim, Bavaria. It preserves fossils dating back to the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigra ...

at Daiting

Daiting is a municipality in the district of Donau-Ries in Bavaria in Germany.

Archaeopteryx - Daiting Specimen

An eighth, fragmentary specimen of Archaeopteryx was discovered in the late 1980s in the somewhat younger sediments at Daiting. It ...

, Suevia. Therefore, it is known as the Daiting Specimen, and had been known since 1996 only from a cast, briefly shown at the Naturkundemuseum in Bamberg

Bamberg (, , ; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ''Bambärch'') is a town in Upper Franconia district in Bavaria, Germany, on the river Regnitz close to its confluence with the river Main (river), Main. Bamberg had 79,000 inhabitants in ...

. The original was purchased by palaeontologist Raimund Albertsdörfer in 2009. It was on display for the first time with six other original fossils of ''Archaeopteryx'' at the Munich Mineral Show in October 2009. The Daiting Specimen was subsequently named ''Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi'' by Kundrat et al. (2018). After a lengthy period in a closed private collection, it was moved to the Museum of Evolution at Knuthenborg Safaripark

Knuthenborg Safaripark is a safari park on the island of Lolland in the southeast of Denmark. It is located to the north of Maribo, near Bandholm. It is one of Lolland's major tourist attractions with over 300,000 visitors annually, and is the ...

(Denmark) in 2022, where it has since been on display and also been made available for researchers.

Another fragmentary fossil was found in 2000. It is in private possession and, since 2004, on loan to the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum in Solnhofen, so it is called the Bürgermeister-Müller Specimen; the institute itself officially refers to it as the "Exemplar of the families Ottman & Steil, Solnhofen". As the fragment represents the remains of a single wing of ''Archaeopteryx'', it is colloquially known as "chicken wing".

Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the

Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the Wyoming Dinosaur Center

The Wyoming Dinosaur Center is located in Thermopolis, Wyoming and is one of the few dinosaur museums in the world to have excavation sites within driving distance. The museum displays the Thermopolis Specimen of ''Archaeopteryx'', which is one of ...

in Thermopolis, Wyoming

Thermopolis is the county seat and most populous town in Hot Springs County, Wyoming, United States. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the town population was 2,725.

Thermopolis, Greek for "hot city", is home to numerous natural hot springs, in which ...

, it has the best-preserved head and feet; most of the neck and the lower jaw have not been preserved. The "Thermopolis" specimen was described on 2 December 2005 ''Science'' journal article as "A well-preserved ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen with theropod features"; it shows that ''Archaeopteryx'' lacked a reversed toe—a universal feature of birds—limiting its ability to perch on branches and implying a terrestrial or trunk-climbing lifestyle. This has been interpreted as evidence of theropod

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodom ...

ancestry. In 1988, Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology. He is best known for his work and research on theropoda, theropod dinosaurs and his detailed illustrations, both l ...

claimed to have found evidence of a hyperextensible second toe, but this was not verified and accepted by other scientists until the Thermopolis specimen was described. "Until now, the feature was thought to belong only to the species' close relatives, the deinonychosaurs." The Thermopolis Specimen was assigned to ''Archaeopteryx siemensii'' in 2007. The specimen is considered to represent the most complete and best-preserved ''Archaeopteryx'' remains yet.

The discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced in 2011; it was described in 2014. It is one of the more complete specimens, but is missing much of the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name. Palaeontologists of the

The discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced in 2011; it was described in 2014. It is one of the more complete specimens, but is missing much of the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name. Palaeontologists of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich, LMU or LMU Munich; ) is a public university, public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Originally established as the University of Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke ...

studied the specimen, which revealed previously unknown features of the plumage, such as feathers on both the upper and lower legs and metatarsus

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

, and the only preserved tail tip.

A twelfth specimen had been discovered by an amateur collector in 2010 at the Schamhaupten quarry, but the finding was only announced in February 2014. It was scientifically described in 2018. It represents a complete and mostly articulated skeleton with skull. It is the only specimen lacking preserved feathers. It is from the Painten Formation

The Painten Formation is a geologic formation in Germany. It preserves fossils dating back to the Tithonian stage of the Late Jurassic period.Mörnsheim Formation

The Mörnsheim Formation is a geologic formation in Germany, near Daiting and Mörnsheim, Bavaria. It preserves fossils dating back to the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigra ...

. It preserves the right forelimb, shoulder, and fragments of the other limbs, with various features of the shoulder and forelimb resembling ''Archaeopteryx'' more than any other avialan within the Mörnsheim Formation. However, due to the fragmentary nature of this specimen, it cannot be assigned to a specific species within ''Archaeopteryx''.

The existence of a fourteenth specimen (the Chicago specimen) was first informally announced in 2024 by the Field Museum

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educationa ...

in Chicago, US. One of two specimens in an institution outside Europe, the specimen was originally identified in a private collection in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, and had been acquired by these collectors in 1990, prior to Germany's 2015 ban on exporting ''Archaeopteryx'' specimens. The specimen was acquired by the Field Museum in 2022, and went on public display in 2024 following two years of preparation. In 2025, the paleornithologist Jingmai O'Connor

Jingmai Kathleen O'Connor ( ''Zōu Jīngméi''; born August 26, 1983) is a paleontologist who works as a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois.

Biography

O'Connor is from Pasadena, California. Her mother is a geologist. O'Connor says ...

and colleagues officially published a study describing this fourteenth specimen, reporting the first known tertials

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

(specialized inner secondary flight feathers) and other novel features in ''Archaeopteryx''.

Authenticity

Beginning in 1985, an amateur group including astronomerFred Hoyle

Sir Fred Hoyle (24 June 1915 – 20 August 2001) was an English astronomer who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and was one of the authors of the influential B2FH paper, B2FH paper. He also held controversial stances on oth ...

and physicist Lee Spetner

Lee M. Spetner (; January 17, 1927 – August 9, 2024) was an American and Israeli creationist author, mechanical engineer, applied biophysicist, and physicist, known best for his disagreements with the modern synthesis. In spite of his opposit ...

, published a series of papers claiming that the feathers on the Berlin and London specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' were forged. Their claims were repudiated by Alan J. Charig and others at the Natural History Museum in London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and ...

. Most of their supposed evidence for a forgery was based on unfamiliarity with the processes of lithification

Lithification (from the Ancient Greek word ''lithos'' meaning 'rock' and the Latin-derived suffix ''-ific'') is the process in which sediments compact under pressure, expel connate fluids, and gradually become solid rock. Essentially, lithificati ...

; for example, they proposed that, based on the difference in texture associated with the feathers, feather impressions were applied to a thin layer of cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel ( aggregate) together. Cement mi ...

, without realizing that feathers themselves would have caused a textural difference. They also misinterpreted the fossils, claiming that the tail was forged as one large feather, when visibly this is not the case. In addition, they claimed that the other specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' known at the time did not have feathers, which is incorrect; the Maxberg and Eichstätt specimens have obvious feathers.

They also expressed disbelief that slabs would split so smoothly, or that one half of a slab containing fossils would have good preservation, but not the counterslab. These are common properties of Solnhofen fossils, because the dead animals would fall onto hardened surfaces, which would form a natural plane for the future slabs to split along and would leave the bulk of the fossil on one side and little on the other.

Finally, the motives they suggested for a forgery are not strong, and are contradictory; one is that Richard Owen wanted to forge evidence in support of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which is unlikely given Owen's views toward Darwin and his theory. The other is that Owen wanted to set a trap for Darwin, hoping the latter would support the fossils so Owen could discredit him with the forgery; this is unlikely because Owen wrote a detailed paper on the London specimen, so such an action would certainly backfire.

Charig ''et al.'' pointed to the presence of hairline cracks in the slabs running through both rock and fossil impressions, and mineral growth over the slabs that had occurred before discovery and preparation, as evidence that the feathers were original. Spetner ''et al.'' then attempted to show that the cracks would have propagated naturally through their postulated cement layer, but neglected to account for the fact that the cracks were old and had been filled with calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, and thus were not able to propagate. They also attempted to show the presence of cement on the London specimen through X-ray spectroscopy

X-ray spectroscopy is a general term for several Spectroscopy, spectroscopic techniques for characterization of materials by using x-ray radiation.

Characteristic X-ray spectroscopy

When an electron from the inner shell of an atom is excited b ...

, and did find something that was not rock; it was not cement either, and is most probably a fragment of silicone rubber left behind when moulds were made of the specimen. Their suggestions have not been taken seriously by palaeontologists, as their evidence was largely based on misunderstandings of geology, and they never discussed the other feather-bearing specimens, which have increased in number since then. Charig ''et al.'' reported a discolouration: a dark band between two layers of limestone – they say it is the product of sedimentation. It is natural for limestone to take on the colour of its surroundings and most limestones are coloured (if not colour banded) to some degree, so the darkness was attributed to such impurities. They also mention that a complete absence of air bubbles in the rock slabs is further proof that the specimen is authentic.

Description

raven

A raven is any of several large-bodied passerine bird species in the genus '' Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between crows and ravens; the two names are assigne ...

, with broad wings that were rounded at the ends and a long tail compared to its body length. It could reach up to in body length and in wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the opposite wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingsp ...

, with an estimated mass of . ''Archaeopteryx'' feathers, although less documented than its other features, were very similar in structure to modern-day bird feathers. Despite the presence of numerous avian features, ''Archaeopteryx'' had many non-avian theropod dinosaur

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodomor ...

characteristics. Unlike modern birds, ''Archaeopteryx'' had small teeth, as well as a long bony tail, features which ''Archaeopteryx'' shared with other dinosaurs of the time.

Because it displays features common to both birds and non-avian dinosaurs, ''Archaeopteryx'' has often been considered a link between them. In the 1970s, John Ostrom

John Harold Ostrom (February 18, 1928 – July 16, 2005) was an American paleontologist who revolutionized the modern understanding of dinosaurs. Ostrom's work inspired what his pupil Robert T. Bakker has termed a " dinosaur renaissance".

Begin ...

, following Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

's lead in 1868, argued that birds evolved within theropod dinosaurs and ''Archaeopteryx'' was a critical piece of evidence for this argument; it had several avian features, such as a wishbone, flight feathers, wings, and a partially reversed first toe along with dinosaur and theropod features. For instance, it has a long ascending process of the ankle bone

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known as the tarsus. The tarsus forms the lower part of the ankle joint. It transmits the entire weight of the body ...

, interdental plate

The interdental plate refers to the bone-filled mesial-distal region between the teeth. The word "''interdental''" is a combination of "''inter''" + "''dental''" (meaning "''between the teeth''") which originated in approximately 1870. In paleobi ...

s, an obturator process of the ischium

The ischium (; : is ...

, and long chevrons in the tail. In particular, Ostrom found that ''Archaeopteryx'' was remarkably similar to the theropod family Dromaeosauridae

Dromaeosauridae () is a family of feathered coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous Period. The name Dromaeosauridae means 'running lizards', from ...

.

Archaeopteryx had three separate digits on each fore-leg each ending with a "claw". Few birds have such features. Some birds, such as duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family (biology), family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and goose, geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfam ...

s, swan

Swans are birds of the genus ''Cygnus'' within the family Anatidae. The swans' closest relatives include the goose, geese and ducks. Swans are grouped with the closely related geese in the subfamily Anserinae where they form the tribe (biology) ...

s, Jacanas (''Jacana'' sp.), and the hoatzin

The hoatzin ( ) or hoactzin ( ) (''Opisthocomus hoazin'') is a species of tropical bird found in swamps, riparian forests, and mangroves of the Amazon and the Orinoco basins in South America. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Opisthoco ...

(''Opisthocomus hoazin''), have them concealed beneath their leg-feathers.

Plumage

Specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' were most notable for their well-developed

Specimens of ''Archaeopteryx'' were most notable for their well-developed flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

s. They were markedly asymmetrical and showed the structure of flight feathers in modern birds, with vanes given stability by a barb

Barb or the BARBs or ''variation'' may refer to:

People

* Barb (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

* Barb, a term used by fans of Nicki Minaj to refer to themselves

* The Barbs, a band

Places

* Barb, ...

-barbule

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an example ...

- barbicel arrangement. The tail feathers were less asymmetrical, again in line with the situation in modern birds and also had firm vanes. The thumb

The thumb is the first digit of the hand, next to the index finger. When a person is standing in the medical anatomical position (where the palm is facing to the front), the thumb is the outermost digit. The Medical Latin English noun for thumb ...

did not yet bear a separately movable tuft of stiff feathers.

The body plumage of ''Archaeopteryx'' is less well-documented and has only been properly researched in the well-preserved Berlin specimen

''Archaeopteryx'' fossils from the quarries of Solnhofen Plattenkalk, Solnhofen limestone represent the most famous and well-known fossils from this area. They are highly significant to paleontology and evolution of birds, avian evolution in t ...

. Thus, as more than one species seems to be involved, the research into the Berlin specimen's feathers does not necessarily hold true for the rest of the species of ''Archaeopteryx''. In the Berlin specimen, there are "trousers" of well-developed feathers on the legs; some of these feathers seem to have a basic contour feather structure, but are somewhat decomposed (they lack barbicels as in ratite

Ratites () are a polyphyletic group consisting of all birds within the infraclass Palaeognathae that lack keels and cannot fly. They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, the exception being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal ...

s). In part they are firm and thus capable of supporting flight.

A patch of pennaceous feather

The pennaceous feather is a type of feather present in most modern birds and in some other species of maniraptoriform dinosaurs.

Description

A pennaceous feather has a stalk or quill. Its basal part, called a ''calamus'', is embedded in the sk ...

s is found running along its back, which was quite similar to the contour feathers of the body plumage of modern birds in being symmetrical and firm, although not as stiff as the flight-related feathers. Apart from that, the feather traces in the Berlin specimen are limited to a sort of "proto- down" not dissimilar to that found in the dinosaur ''Sinosauropteryx

''Sinosauropteryx'' (meaning "Chinese reptilian wing") is an extinct genus of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Described in 1996, it was the first dinosaur taxon outside of Avialae (birds and their immediate relatives) to be found with eviden ...

'': decomposed and fluffy, and possibly even appearing more like fur than feathers in life (although not in their microscopic structure). These occur on the remainder of the body—although some feathers did not fossilize and others were obliterated during preparation, leaving bare patches on specimens—and the lower neck.

There is no indication of feathering on the upper neck and head. While these conceivably may have been nude, this may still be an artefact of preservation. It appears that most ''Archaeopteryx'' specimens became embedded in anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

sediment after drifting some time on their backs in the sea—the head, neck and the tail are generally bent downward, which suggests that the specimens had just started to rot when they were embedded, with tendons and muscle relaxing so that the characteristic shape (death pose

Non-avian dinosaur and bird fossils are frequently found in a characteristic posture consisting of head thrown back, tail extended, and mouth wide open. The cause of this posture—often called a "death pose"—has been a matter of scientific deba ...

) of the fossil specimens was achieved. This would mean that the skin already was softened and loose, which is bolstered by the fact that in some specimens the flight feathers were starting to detach at the point of embedding in the sediment. So it is hypothesized that the pertinent specimens moved along the sea bed in shallow water for some time before burial, the head and upper neck feathers sloughing off, while the more firmly attached tail feathers remained.

Colouration

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen. Using

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen. Using scanning electron microscopy

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) is a type of electron microscope that produces images of a sample by scanning the surface with a focused beam of electrons. The electrons interact with atoms in the sample, producing various signals that ...

technology and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, the team was able to detect the structure of melanosome

A melanosome is an organelle found in animal cells and is the site for synthesis, storage and transport of melanin, the most common light-absorbing pigment found in the animal kingdom. Melanosomes are responsible for color and photoprotectio ...

s in the isolated feather specimen described in 1861. The resultant measurements were then compared to those of 87modern bird species, and the original colour was calculated with a 95% likelihood to be black. The feather was determined to be black throughout, with heavier pigmentation in the distal tip. The feather studied was most probably a dorsal covert

Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups who do not have the "need to know", perhaps while sharing it with other individuals. That which is kept hidden is known as the secret.

Secrecy is often controver ...

, which would have partly covered the primary feathers on the wings. The study does not mean that ''Archaeopteryx'' was entirely black, but suggests that it had some black colouration which included the coverts. Carney pointed out that this is consistent with what is known of modern flight characteristics, in that black melanosomes have structural properties that strengthen feathers for flight. In a 2013 study published in the ''Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry'', new analyses of ''Archaeopteryx''s feathers revealed that the animal may have had complex light- and dark-coloured plumage, with heavier pigmentation in the distal tips and outer vanes. This analysis of colour distribution was based primarily on the distribution of sulphate within the fossil. An author on the previous ''Archaeopteryx'' colour study argued against the interpretation of such biomarkers as an indicator of eumelanin in the full ''Archaeopteryx'' specimen. Carney and other colleagues also argued against the 2013 study's interpretation of the sulphate and trace metals, and in a 2020 study published in ''Scientific Reports'' demonstrated that the isolated covert feather was entirely matte black (as opposed to black and white, or iridescent) and that the remaining "plumage patterns of ''Archaeopteryx'' remain unknown".

Classification

Today, fossils of the genus ''Archaeopteryx'' are usually assigned to one or two species, ''A. lithographica'' and ''A. siemensii'', but their taxonomic history is complicated. Ten names have been published for the handful of specimens. As interpreted today, the name ''A. lithographica'' only referred to the single feather described by

Today, fossils of the genus ''Archaeopteryx'' are usually assigned to one or two species, ''A. lithographica'' and ''A. siemensii'', but their taxonomic history is complicated. Ten names have been published for the handful of specimens. As interpreted today, the name ''A. lithographica'' only referred to the single feather described by Meyer

Meyer may refer to:

People

*Meyer (surname), listing people so named

* Meyer (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the name

Companies

* Meyer Burger, a Swiss mechanical engineering company

* Meyer Corporation

* Meyer Sound Labo ...

. In 1954 Gavin de Beer

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (1 November 1899 – 21 June 1972) was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors''. He was director of the Natural History Museum, Lond ...

concluded that the London specimen was the holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

. In 1960, Swinton accordingly proposed that the name ''Archaeopteryx lithographica'' be placed on the official genera list making the alternative names ''Griphosaurus'' and ''Griphornis'' invalid. The ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

, implicitly accepting De Beer's standpoint, did indeed suppress the plethora of alternative names initially proposed for the first skeleton specimens, which mainly resulted from the acrimonious dispute between Meyer and his opponent Johann Andreas Wagner

Johann Andreas Wagner (21 March 1797 – 17 December 1861) was a German palaeontologist, zoologist and archaeologist who wrote several important works on palaeontology. He was also a pioneer of biogeographical theory.

Career

Wagner was born ...

(whose ''Griphosaurus problematicus''—'problematic riddle

A riddle is a :wikt:statement, statement, question, or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: ''enigmas'', which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or Allegory, alleg ...

-lizard'—was a vitriolic sneer at Meyer's ''Archaeopteryx''). In addition, in 1977, the Commission ruled that the first species name of the Haarlem specimen, ''crassipes'', described by Meyer as a pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

before its true nature was realized, was not to be given preference over ''lithographica'' in instances where scientists considered them to represent the same species.

It has been noted that the feather, the first specimen of ''Archaeopteryx'' described, does not correspond well with the flight-related feathers of ''Archaeopteryx''. It certainly is a flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

of a contemporary species, but its size and proportions indicate that it may belong to another, smaller species of feathered theropod, of which only this feather is known so far. As the feather had been designated the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

, the name ''Archaeopteryx'' should then no longer be applied to the skeletons, thus creating significant nomenclatorial confusion. In 2007, two sets of scientists therefore petitioned the ICZN requesting that the London specimen explicitly be made the type by designating it as the new holotype specimen, or neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes ...

. This suggestion was upheld by the ICZN after four years of debate, and the London specimen was designated the neotype on 3 October 2011.

Below is a

Below is a cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

published in 2013 by Godefroit ''et al.''

Species

It has been argued that all the specimens belong to the same species, ''A. lithographica''. Differences do exist among the specimens, and while some researchers regard these as due to the different ages of the specimens, some may be related to actual species diversity. In particular, the Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis specimens differ from the London, Berlin, and Haarlem specimens in being smaller or much larger, having different finger proportions, having more slender snouts lined with forward-pointing teeth, and the possible presence of a

It has been argued that all the specimens belong to the same species, ''A. lithographica''. Differences do exist among the specimens, and while some researchers regard these as due to the different ages of the specimens, some may be related to actual species diversity. In particular, the Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis specimens differ from the London, Berlin, and Haarlem specimens in being smaller or much larger, having different finger proportions, having more slender snouts lined with forward-pointing teeth, and the possible presence of a sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

. Due to these differences, most individual specimens have been given their own species name at one point or another. The Berlin specimen has been designated as ''Archaeornis siemensii'', the Eichstätt specimen as ''Jurapteryx recurva'', the Munich specimen as ''Archaeopteryx bavarica'', and the Solnhofen specimen as ''Wellnhoferia grandis''.

In 2007, a review of all well-preserved specimens including the then-newly discovered Thermopolis specimen concluded that two distinct species of ''Archaeopteryx'' could be supported: ''A. lithographica'' (consisting of at least the London and Solnhofen specimens), and ''A. siemensii'' (consisting of at least the Berlin, Munich, and Thermopolis specimens). The two species are distinguished primarily by large flexor tubercles

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projection, b ...

on the foot claws in ''A. lithographica'' (the claws of ''A. siemensii'' specimens being relatively simple and straight). ''A. lithographica'' also had a constricted portion of the crown in some teeth and a stouter metatarsus. A supposed additional species, ''Wellnhoferia grandis'' (based on the Solnhofen specimen), seems to be indistinguishable from ''A. lithographica'' except in its larger size.

Synonyms

If two names are given, the first denotes the original describer of the "species", the second the author on whom the given name combination is based. As always inzoological nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

, putting an author's name in parentheses denotes that the taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

was originally described in a different genus.

* ''Archaeopteryx lithographica'' Meyer, 1861 onserved name/small>

**''Archaeopterix lithographica'' Anon., 1861 'lapsus''/small>

** ''Griphosaurus problematicus'' Wagner, 1862 ejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607/small>

** ''Griphornis longicaudatus'' Owen ''vide'' Woodward, 1862 ejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607/small>

** ''Archaeopteryx macrura'' Owen, 1862 ejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607/small>

** ''Archaeopteryx oweni'' Petronievics, 1917 ejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607/small>

** ''Archaeopteryx recurva'' Howgate, 1984

** ''Jurapteryx recurva'' (Howgate, 1984) Howgate, 1985

** ''Wellnhoferia grandis'' Elżanowski, 2001

* ''Archaeopteryx siemensii'' Dames, 1897

**''Archaeornis siemensii'' (Dames, 1897) Petronievics, 1917

** ''Archaeopteryx bavarica'' Wellnhofer, 1993

''"Archaeopteryx" vicensensis'' (Anon. ''fide'' Lambrecht, 1933) is a ''nomen nudum

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published ...

'' for what appears to be an undescribed pterosaur.

Phylogenetic position

Avimimus

''Avimimus'' ( ), meaning "bird mimic" (Latin ''avis'' = bird + ''mimus'' = mimic), is a genus of oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur, named for its bird-like characteristics, that lived in the late Cretaceous in what is now Mongolia, around 85 t ...

'' was more likely to be the ancestor of all birds than ''Archaeopteryx''. Barsbold (1983) and Zweers and Van den Berge (1997) noted that many maniraptora

Maniraptora is a clade of coelurosaurian dinosaurs which includes the birds and the non-avian dinosaurs that were more closely related to them than to ''Ornithomimus velox''. It contains the major subgroups Avialae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, ...

n lineages are extremely birdlike, and they suggested that different groups of birds may have descended from different dinosaur ancestors.

The discovery of the closely related ''Xiaotingia

''Xiaotingia'' is a genus of Paraves, paravian theropod dinosaur, possibly an Anchiornithidae, anchiornithid, from Middle Jurassic or early Late Jurassic deposits of western Liaoning, China. It contains a single species, ''Xiaotingia zhengi''.

D ...

'' in 2011 led to new phylogenetic analyses that suggested that ''Archaeopteryx'' is a deinonychosaur

Deinonychosauria is a clade of paravian dinosaurs which lived from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous periods. Fossils have been found across the globe in North America, Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, and Antarctica,Case, J.A., Marti ...

rather than an avialan, and therefore, not a "bird" under most common uses of that term. A more thorough analysis was published soon after to test this hypothesis, and failed to arrive at the same result; it found ''Archaeopteryx'' in its traditional position at the base of ''Avialae'', while ''Xiaotingia'' was recovered as a basal dromaeosaurid or troodontid. The authors of the follow-up study noted that uncertainties still exist, and that it may not be possible to state confidently whether or not ''Archaeopteryx'' is a member of Avialae or not, barring new and better specimens of relevant species.

Phylogenetic studies conducted by Senter, ''et al.'' (2012) and Turner, Makovicky, and Norell (2012) also found ''Archaeopteryx'' to be more closely related to living birds than to dromaeosaurids and troodontids. On the other hand, Godefroit ''et al.'' (2013) recovered ''Archaeopteryx'' as more closely related to dromaeosaurids and troodontids in the analysis included in their description of ''Eosinopteryx brevipenna

''Eosinopteryx'' is an extinct genus of theropod dinosaurs known to the Late Jurassic epoch of China. It contains a single species, ''Eosinopteryx brevipenna''. Some researchers consider it a junior synonym of ''Anchiornis.''

Discovery and namin ...

''. The authors used a modified version of the matrix from the study describing ''Xiaotingia'', adding ''Jinfengopteryx elegans

''Jinfengopteryx'' (from , 'golden phoenix', the queen of birds in Chinese folklore, and , meaning 'feather') is a genus of maniraptoran dinosaur. It was found in the Qiaotou Member of the Huajiying Formation of Hebei Province, China, and is the ...

'' and ''Eosinopteryx brevipenna'' to it, as well as adding four additional characters related to the development of the plumage. Unlike the analysis from the description of ''Xiaotingia'', the analysis conducted by Godefroit, ''et al.'' did not find ''Archaeopteryx'' to be related particularly closely to ''Anchiornis'' and ''Xiaotingia'', which were recovered as basal troodontids instead.

Agnolín and Novas (2013) found ''Archaeopteryx'' and (possibly synonymous) ''Wellnhoferia

''Wellnhoferia'' (named after Peter Wellnhofer) is a genus of early prehistoric bird-like theropod dinosaur closely related to ''Archaeopteryx''. It lived in what is now Germany, during the Late Jurassic. While ''Wellnhoferia'' was similar to '' ...

'' to form a clade sister to the lineage including ''Jeholornis'' and Pygostylia, with Microraptoria

Microraptoria (Greek, μίκρος, ''mīkros'': "small"; Latin, ''raptor'': "one who seizes") is a clade of basal Dromaeosauridae, dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs. Definitive microraptorians lived during the Barremian to Aptian stages of the Ear ...

, Unenlagiinae

Unenlagiinae is a subfamily of long-snouted paravian theropods. They are traditionally considered to be members of Dromaeosauridae, though some authors place them into their own family, Unenlagiidae, sometimes alongside the subfamily Halszkar ...

, and the clade containing ''Anchiornis'' and ''Xiaotingia'' being successively closer outgroups to the Avialae (defined by the authors as the clade stemming from the last common ancestor of ''Archaeopteryx'' and Aves). Another phylogenetic study by Godefroit, ''et al.'', using a more inclusive matrix than the one from the analysis in the description of ''Eosinopteryx brevipenna'', also found ''Archaeopteryx'' to be a member of Avialae (defined by the authors as the most inclusive clade containing ''Passer domesticus

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pale brown and grey, ...

'', but not ''Dromaeosaurus albertensis

''Dromaeosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (middle late Campanian and Maastrichtian), sometime between 80 and 69 million years ago, in Alberta, Canada and the western United ...

'' or ''Troodon formosus

''Troodon'' ( ; ''Troödon'' in older sources) is a controversial genus of relatively small, bird-like theropod dinosaurs definitively known from the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous period (about 77 million years ago). It includes at l ...

''). ''Archaeopteryx'' was found to form a grade

Grade most commonly refers to:

* Grading in education, a measurement of a student's performance by educational assessment (e.g. A, pass, etc.)

* A designation for students, classes and curricula indicating the number of the year a student has reach ...

at the base of Avialae with ''Xiaotingia'', ''Anchiornis'', and ''Aurornis

''Aurornis'' is an extinct genus of anchiornithid theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic period of China. The genus ''Aurornis'' contains a single known species, ''Aurornis xui'' (). ''Aurornis xui'' may be the most basal ("primitive") avialan di ...

''. Compared to ''Archaeopteryx'', ''Xiaotingia'' was found to be more closely related to extant birds, while both ''Anchiornis'' and ''Aurornis

''Aurornis'' is an extinct genus of anchiornithid theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic period of China. The genus ''Aurornis'' contains a single known species, ''Aurornis xui'' (). ''Aurornis xui'' may be the most basal ("primitive") avialan di ...

'' were found to be more distantly so.

Hu ''et al''. (2018), Wang ''et al''. (2018) and Hartman ''et al''. (2019) found ''Archaeopteryx'' to have been a deinonychosaur instead of an avialan. More specifically, it and closely related taxa were considered basal deinonychosaurs, with dromaeosaurids and troodontids forming together a parallel lineage within the group. Because Hartman ''et al''. found ''Archaeopteryx'' isolated in a group of flightless deinonychosaurs (otherwise considered " anchiornithids"), they considered it highly probable that this animal evolved flight independently from bird ancestors (and from ''Microraptor'' and '' Yi''). The following cladogram illustrates their hypothesis regarding the position of ''Archaeopteryx'':

The authors, however, found that the ''Archaeopteryx'' being an avialan was only slightly less likely than this hypothesis, and as likely as Archaeopterygidae and Troodontidae being sister clades.

Palaeobiology

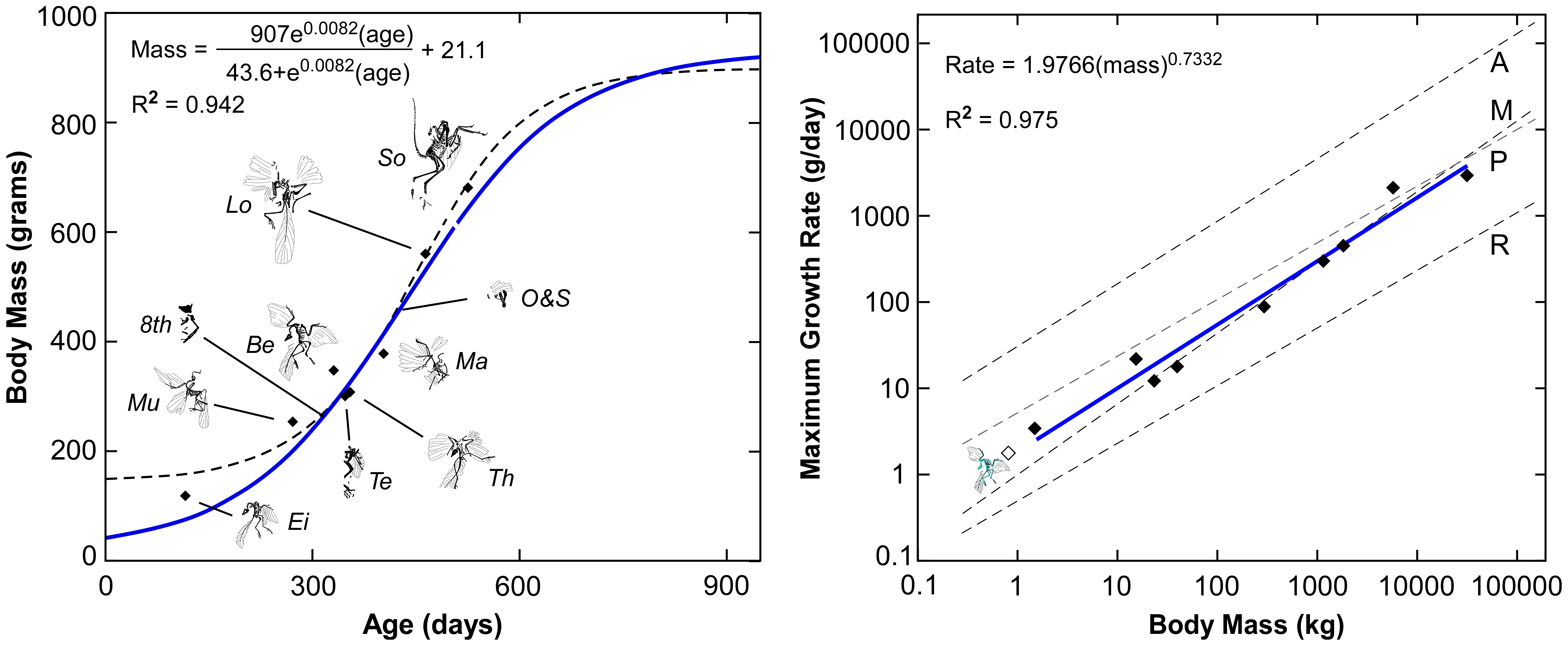

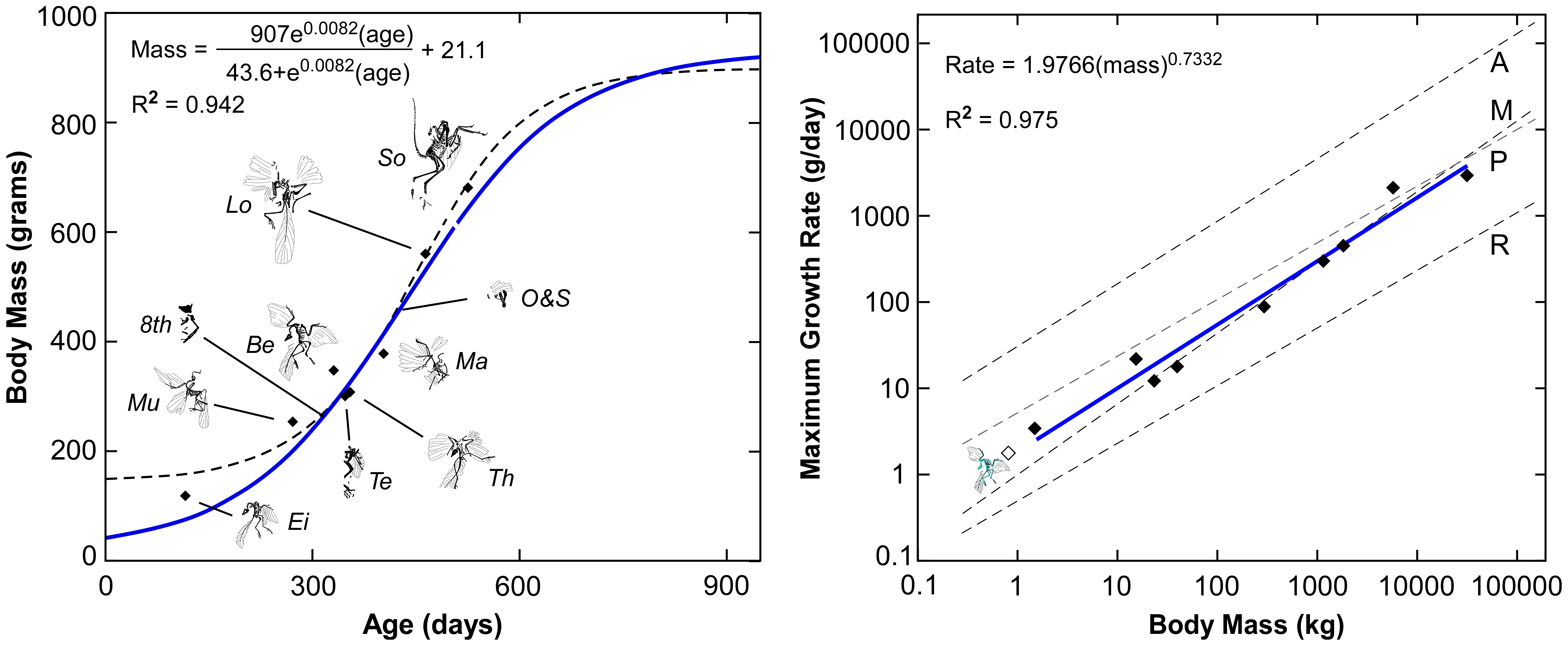

Flight