Appalachia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Appalachia ( ) is a

Since Appalachia lacks definite physiographical or topographical boundaries, there has been some disagreement over what the region encompasses. The most commonly used modern definition of Appalachia is the one initially defined by the

Since Appalachia lacks definite physiographical or topographical boundaries, there has been some disagreement over what the region encompasses. The most commonly used modern definition of Appalachia is the one initially defined by the  The first major attempt to map Appalachia as a distinctive cultural region came in the 1890s with the efforts of Berea College president William Goodell Frost, whose "Appalachian America" included 194 counties in 8 states.John Alexander Williams, ''Appalachia: A History'' (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 2002) In 1921, John C. Campbell published ''The Southern Highlander and His Homeland,'' in which he modified Frost's map to include 254 counties in 9 states. A landmark survey of the region in the following decade by the

The first major attempt to map Appalachia as a distinctive cultural region came in the 1890s with the efforts of Berea College president William Goodell Frost, whose "Appalachian America" included 194 counties in 8 states.John Alexander Williams, ''Appalachia: A History'' (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 2002) In 1921, John C. Campbell published ''The Southern Highlander and His Homeland,'' in which he modified Frost's map to include 254 counties in 9 states. A landmark survey of the region in the following decade by the

While exploring inland along the northern coast of

While exploring inland along the northern coast of

European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots—later known as " Scotch-Irish", a group mostly originating from southern Scotland and northern England, many of whom had settled in Ulster Ireland prior to migrating to America—who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from prejudice as the Scotch-Irish were looked down upon by other more powerful elements in society. Others included

European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots—later known as " Scotch-Irish", a group mostly originating from southern Scotland and northern England, many of whom had settled in Ulster Ireland prior to migrating to America—who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from prejudice as the Scotch-Irish were looked down upon by other more powerful elements in society. Others included

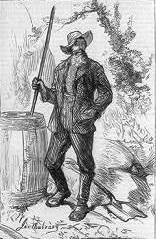

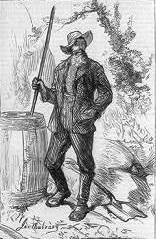

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-

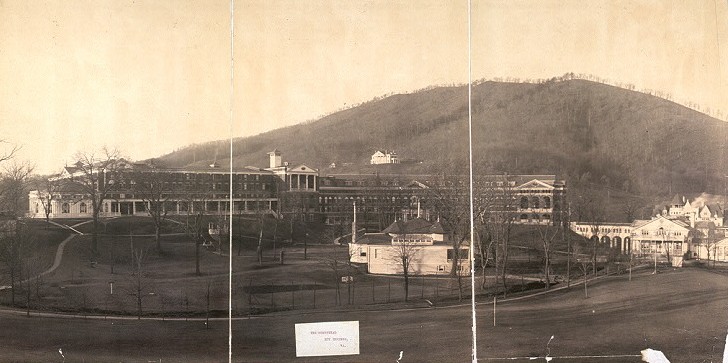

After the Civil War, northern Appalachia experienced an economic boom. At the same time, economies in the southern region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction. Pittsburgh as well as Knoxville grew into major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area of north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes with manufacturing booms in

After the Civil War, northern Appalachia experienced an economic boom. At the same time, economies in the southern region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction. Pittsburgh as well as Knoxville grew into major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area of north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes with manufacturing booms in

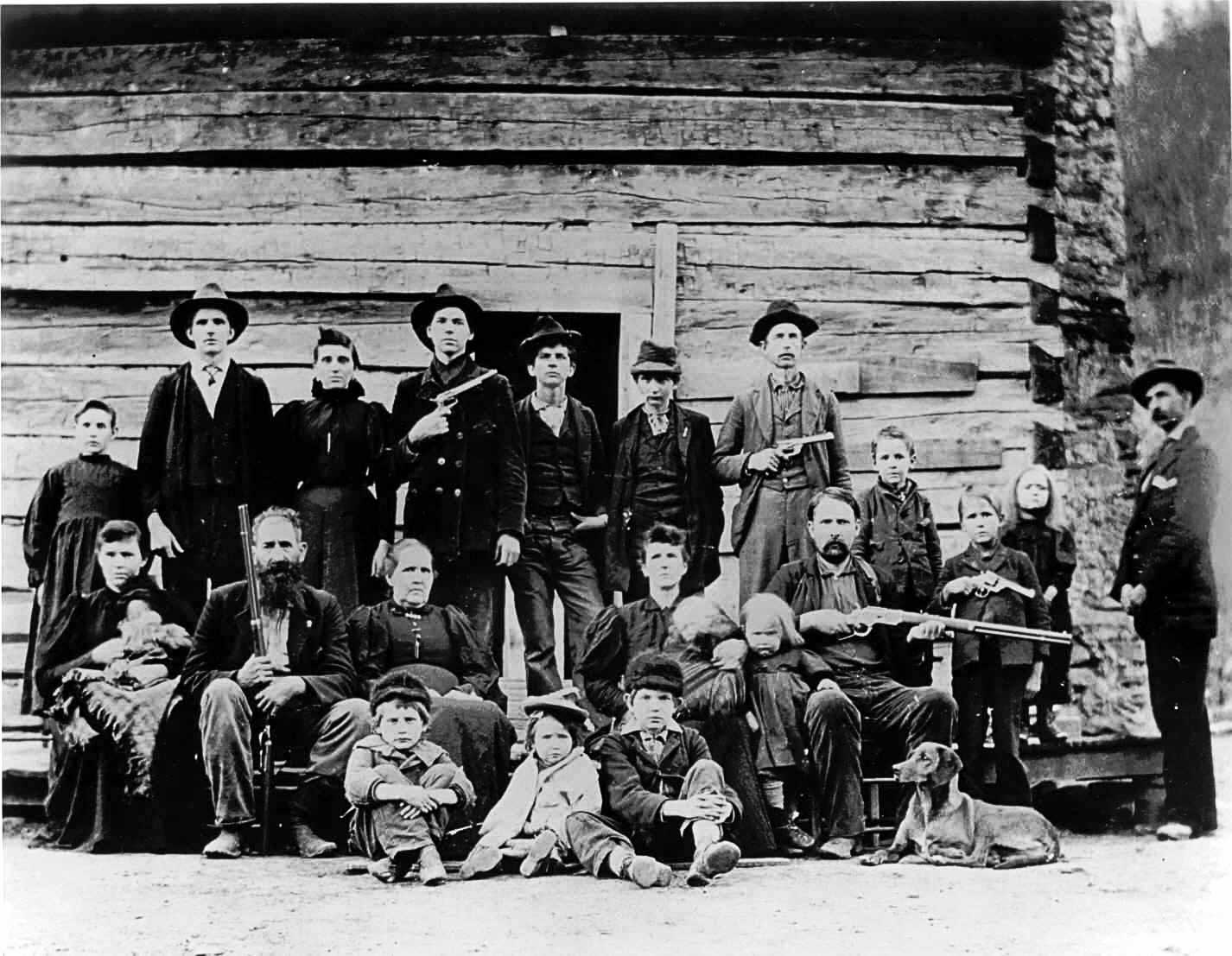

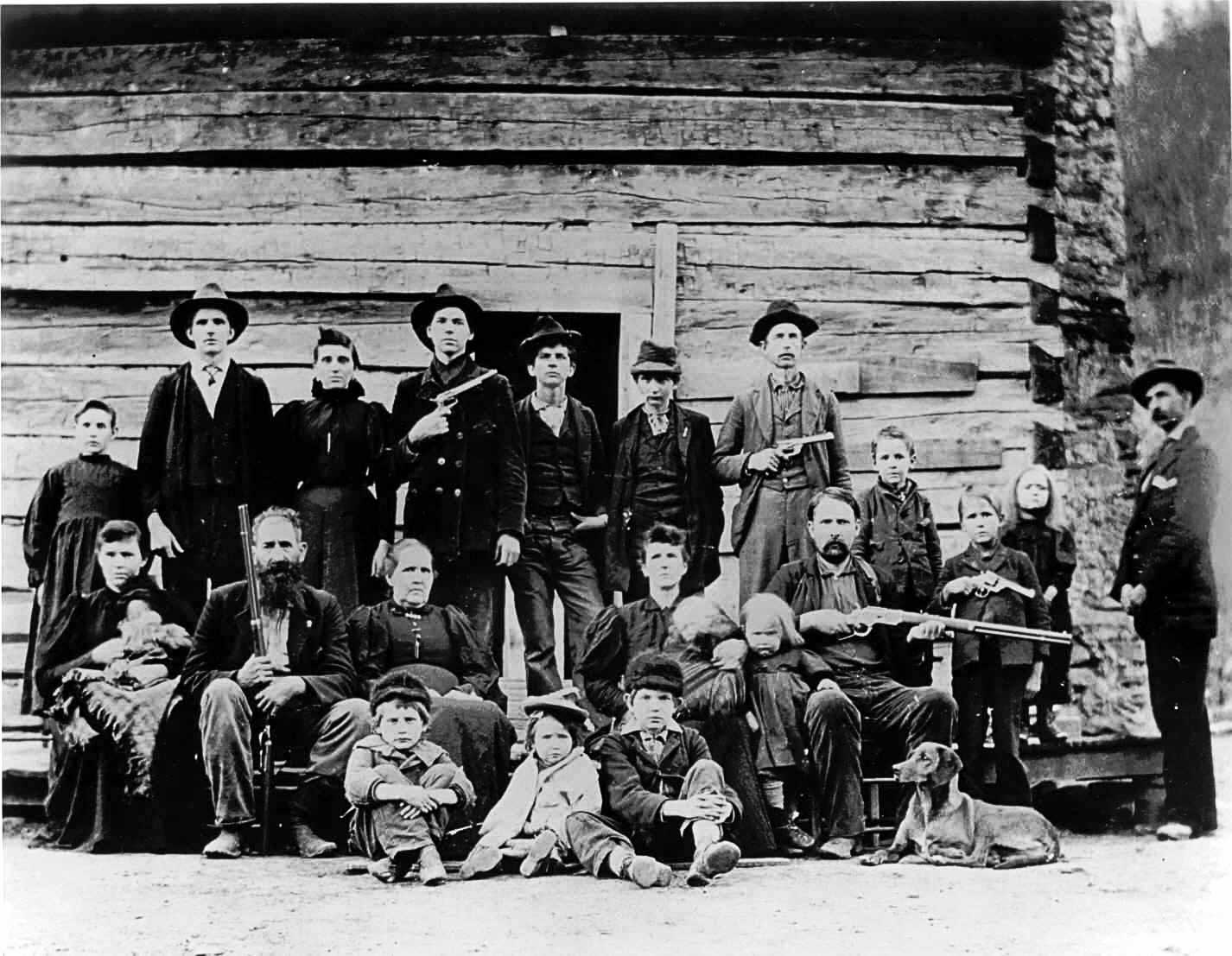

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became nationally known for its violent

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became nationally known for its violent

Christianity is the main religion in Appalachia, which is characterized by a sense of independence and a distrust of religious hierarchies, both rooted in the evangelical tendencies of the region's pioneers, many of whom had been influenced by the Holiness movement and " New Light" movement in England. Many of the denominations brought from Europe underwent modifications or factioning during the Second Great Awakening (especially the Holiness movement) in the early 19th century. Several 18th and 19th-century religious traditions are still practiced in parts of Appalachia, including natural water (or "creek")

Christianity is the main religion in Appalachia, which is characterized by a sense of independence and a distrust of religious hierarchies, both rooted in the evangelical tendencies of the region's pioneers, many of whom had been influenced by the Holiness movement and " New Light" movement in England. Many of the denominations brought from Europe underwent modifications or factioning during the Second Great Awakening (especially the Holiness movement) in the early 19th century. Several 18th and 19th-century religious traditions are still practiced in parts of Appalachia, including natural water (or "creek")

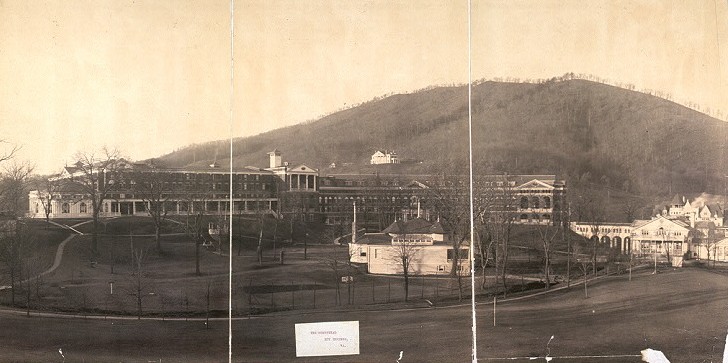

For much of the region's history, education in Appalachia has lagged behind the rest of the nation due in part to struggles with funding from respective state governments and an agrarian-oriented population that often did not see a practical need for formal education. Early education in the region evolved from teaching Christian morality and learning to read the Bible in small,

For much of the region's history, education in Appalachia has lagged behind the rest of the nation due in part to struggles with funding from respective state governments and an agrarian-oriented population that often did not see a practical need for formal education. Early education in the region evolved from teaching Christian morality and learning to read the Bible in small,

Early Appalachian literature typically centered on the observations of people from outside the region, such as Henry Timberlake's ''Memoirs'' (1765) and

Early Appalachian literature typically centered on the observations of people from outside the region, such as Henry Timberlake's ''Memoirs'' (1765) and

Appalachian folklore has a strong mixture of European, Native American (especially

Appalachian folklore has a strong mixture of European, Native American (especially

While the climate of the Appalachian region is suitable for agriculture, the region's hilly terrain greatly limits the size of the average farm, a problem exacerbated by population growth in the latter half of the 19th century. Subsistence agriculture, Subsistence farming was the backbone of the Appalachian economy throughout much of the 19th century, and while economies in places such as western Pennsylvania, the Great Appalachian Valley, Great Valley of Virginia, and the upper Tennessee Valley in east Tennessee, transitioned to a large-scale farming or manufacturing base around the time of the Civil War, subsistence farming remained an important part of the region's economy until the 1950s. In the early 20th century, Appalachian farmers were struggling to mechanize, and abusive farming practices had over the years left much of the already-limited farmland badly eroded. Various federal entities intervened in the 1930s to restore damaged areas and introduce less harmful farming techniques. In recent decades, the concept of sustainable agriculture has been applied to the region's small farms, with some success. Nevertheless, the number of farms in the Appalachian region continues to dwindle, plunging from 354,748 farms on in 1969 to 230,050 farms on in 1997.Best, Michael, and Curtis Wood, Introduction to the Agriculture section in the ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 395–402.

Early Appalachian farmers grew both crops introduced from their native Europe as well as crops native to North America (such as corn and squash). Tobacco has long been an important cash crop in Southern Appalachia, especially since the land is ill-suited for cash crops such as cotton. Apples have been grown in the region since the late 18th century, their cultivation being aided by the presence of thermal belts in the region's mountain valleys. Hogs, which could free range in the region's abundant forests, often on chestnuts, were the most popular livestock among early Appalachian farmers. The American chestnut was also an important human food source until the chestnut blight struck in the 20th century. The early settlers also brought cattle and sheep to the region, which they would typically graze in highland meadows known as Appalachian balds, balds during the growing season when bottomlands were needed for crops. Cattle, mainly the Hereford cattle, Hereford, American Angus, Angus, and Charolais cattle, Charolais breeds, are now the region's chief livestock.

While the climate of the Appalachian region is suitable for agriculture, the region's hilly terrain greatly limits the size of the average farm, a problem exacerbated by population growth in the latter half of the 19th century. Subsistence agriculture, Subsistence farming was the backbone of the Appalachian economy throughout much of the 19th century, and while economies in places such as western Pennsylvania, the Great Appalachian Valley, Great Valley of Virginia, and the upper Tennessee Valley in east Tennessee, transitioned to a large-scale farming or manufacturing base around the time of the Civil War, subsistence farming remained an important part of the region's economy until the 1950s. In the early 20th century, Appalachian farmers were struggling to mechanize, and abusive farming practices had over the years left much of the already-limited farmland badly eroded. Various federal entities intervened in the 1930s to restore damaged areas and introduce less harmful farming techniques. In recent decades, the concept of sustainable agriculture has been applied to the region's small farms, with some success. Nevertheless, the number of farms in the Appalachian region continues to dwindle, plunging from 354,748 farms on in 1969 to 230,050 farms on in 1997.Best, Michael, and Curtis Wood, Introduction to the Agriculture section in the ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 395–402.

Early Appalachian farmers grew both crops introduced from their native Europe as well as crops native to North America (such as corn and squash). Tobacco has long been an important cash crop in Southern Appalachia, especially since the land is ill-suited for cash crops such as cotton. Apples have been grown in the region since the late 18th century, their cultivation being aided by the presence of thermal belts in the region's mountain valleys. Hogs, which could free range in the region's abundant forests, often on chestnuts, were the most popular livestock among early Appalachian farmers. The American chestnut was also an important human food source until the chestnut blight struck in the 20th century. The early settlers also brought cattle and sheep to the region, which they would typically graze in highland meadows known as Appalachian balds, balds during the growing season when bottomlands were needed for crops. Cattle, mainly the Hereford cattle, Hereford, American Angus, Angus, and Charolais cattle, Charolais breeds, are now the region's chief livestock.

The mountains and valleys of Appalachia once contained what seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of timber. The poor roads, lack of railroads, and general inaccessibility of the region, however, prevented large-scale logging in most of the region throughout much of the 19th century. While logging firms were established in the Carolinas and the Kentucky River valley before the Civil War, most major firms preferred to harvest the more accessible timber stands in the Midwestern and Northeastern parts of the country. By the 1880s, these stands had been exhausted, and a spike in the demand for lumber forced logging firms to seek out the virgin forests of Appalachia.Paulson, Linda Daily, "Lumber Industry". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 501–04. The first major logging ventures in Appalachia transported logs using mule teams or rivers, the latter method sometimes employing splash dams. In the 1890s, innovations such as the Shay locomotive, the steam-powered loader, and the steam-powered skidder allowed massive harvesting of the most remote forest sections.

Logging in Appalachia reached its peak in the early 20th century, when firms such as the Ritter Lumber Company cut the virgin forests on an alarming scale, leading to the creation of national forests in 1911 and similar state entities to better manage the region's timber resources. Arguably the most successful logging firm in Appalachia was the Georgia Hardwood Lumber Company, established in 1927 and renamed Georgia-Pacific in 1948 when it expanded nationally. Although logging in Appalachia declined as the industry shifted focus to the Pacific Northwest in the 1950s, rising overseas demand in the 1980s brought a resurgence in Appalachian logging. In 1987, 4,810 lumber firms were operating in the region. In the late 1990s, the Appalachian lumber industry was a multibillion-dollar industry, employing 50,000 people in Tennessee, 26,000 in Kentucky, and 12,000 in West Virginia alone. By 1999, 1.4 million acres were extinguished as a result of deforestation by natural resource industries. Pollution from mining processes and disruption of the land ensued numerous environmental issues. Removal of vegetation and other alterations in the land increased erosion and flooding of surrounding areas. Water quality and aquatic life were also affected.

The mountains and valleys of Appalachia once contained what seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of timber. The poor roads, lack of railroads, and general inaccessibility of the region, however, prevented large-scale logging in most of the region throughout much of the 19th century. While logging firms were established in the Carolinas and the Kentucky River valley before the Civil War, most major firms preferred to harvest the more accessible timber stands in the Midwestern and Northeastern parts of the country. By the 1880s, these stands had been exhausted, and a spike in the demand for lumber forced logging firms to seek out the virgin forests of Appalachia.Paulson, Linda Daily, "Lumber Industry". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 501–04. The first major logging ventures in Appalachia transported logs using mule teams or rivers, the latter method sometimes employing splash dams. In the 1890s, innovations such as the Shay locomotive, the steam-powered loader, and the steam-powered skidder allowed massive harvesting of the most remote forest sections.

Logging in Appalachia reached its peak in the early 20th century, when firms such as the Ritter Lumber Company cut the virgin forests on an alarming scale, leading to the creation of national forests in 1911 and similar state entities to better manage the region's timber resources. Arguably the most successful logging firm in Appalachia was the Georgia Hardwood Lumber Company, established in 1927 and renamed Georgia-Pacific in 1948 when it expanded nationally. Although logging in Appalachia declined as the industry shifted focus to the Pacific Northwest in the 1950s, rising overseas demand in the 1980s brought a resurgence in Appalachian logging. In 1987, 4,810 lumber firms were operating in the region. In the late 1990s, the Appalachian lumber industry was a multibillion-dollar industry, employing 50,000 people in Tennessee, 26,000 in Kentucky, and 12,000 in West Virginia alone. By 1999, 1.4 million acres were extinguished as a result of deforestation by natural resource industries. Pollution from mining processes and disruption of the land ensued numerous environmental issues. Removal of vegetation and other alterations in the land increased erosion and flooding of surrounding areas. Water quality and aquatic life were also affected.

Coal mining is the industry most frequently associated with the region in outsiders' minds, due in part to the fact that the region once produced two-thirds of the nation's coal. At present, however, the mining industry employs just 2% of the Appalachian workforce. The region's vast coalfield covers between northern Pennsylvania and central Alabama, mostly along the Cumberland Plateau and Allegheny Plateau regions. Most mining activity has been concentrated in eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, West Virginia, and western Pennsylvania, with smaller operations in western Maryland,

Coal mining is the industry most frequently associated with the region in outsiders' minds, due in part to the fact that the region once produced two-thirds of the nation's coal. At present, however, the mining industry employs just 2% of the Appalachian workforce. The region's vast coalfield covers between northern Pennsylvania and central Alabama, mostly along the Cumberland Plateau and Allegheny Plateau regions. Most mining activity has been concentrated in eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, West Virginia, and western Pennsylvania, with smaller operations in western Maryland,

The manufacturing industry in Appalachia is rooted primarily in the ironworks and steelworks of early

The manufacturing industry in Appalachia is rooted primarily in the ironworks and steelworks of early

One of the region's oldest industries, tourism became a more important part of the Appalachian economy in the latter half of the 20th century as mining and manufacturing steadily declined.Howell, Benita, "Tourism". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 611–16. In 2000–2001, tourism in Appalachia accounted for nearly $30 billion and over 600,000 jobs. The mountain terrain—with its accompanying scenery and outdoor recreational opportunities—provides the region's primary attractions. The region is home to one of the world's most well-known hiking trails (the

One of the region's oldest industries, tourism became a more important part of the Appalachian economy in the latter half of the 20th century as mining and manufacturing steadily declined.Howell, Benita, "Tourism". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 611–16. In 2000–2001, tourism in Appalachia accounted for nearly $30 billion and over 600,000 jobs. The mountain terrain—with its accompanying scenery and outdoor recreational opportunities—provides the region's primary attractions. The region is home to one of the world's most well-known hiking trails (the

Poverty had plagued Appalachia for many years but was not brought to the attention of the rest of the United States until 1940, when James Agee and Walker Evans published ''Let Us Now Praise Famous Men'', a book that documented families in Appalachia during the Great Depression in words and photos. In 1963, John F. Kennedy established the President's Appalachian Regional Commission. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, crystallized Kennedy's efforts in the form of the

Poverty had plagued Appalachia for many years but was not brought to the attention of the rest of the United States until 1940, when James Agee and Walker Evans published ''Let Us Now Praise Famous Men'', a book that documented families in Appalachia during the Great Depression in words and photos. In 1963, John F. Kennedy established the President's Appalachian Regional Commission. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, crystallized Kennedy's efforts in the form of the

Arc.gov

Martin County, Kentucky, the site of Johnson's 1964 speech, is one such county still ranked as "distressed" by the ARC. As of 2000, the per capita income in Martin County was $10,650, and 37% of its residents lived below the poverty line. Like Johnson, President Bill Clinton brought attention to the remaining areas of poverty in Appalachia. On July 5, 1999, he made a public statement concerning the situation in Tyner, Kentucky. Clinton told the crowd: The region's poverty has been documented often since the early 1960s. John Cohen documents rural lifestyle and culture in ''The High Lonesome Sound'', while Photojournalism, photojournalist Earl Dotter has been visiting and documenting poverty, healthcare and mining in Appalachia for nearly forty years. Another photojournalist, Shelby Lee Adams, has been photographing Appalachian families and lifestyle for decades. Poverty has caused health problems in the region. The diseases of despair, including the opioid epidemic in the United States, and some diseases of poverty are prevalent in Appalachia.

In its summary the report stated that "over 55,000 parcels of property in 80 counties were studied, representing some 20,000,000 acres of land and mineral rights..." It found that "41% of the 20 million acres of land and minerals...are held by only 50 private owners and 10 government agencies. The federal government is the single largest owner in Appalachia, holding over 2,000,000 acres." The study found that the extractive industries, i.e., timber, coal, etc., were "greatly under-assessed for property tax purposes. Over 75% of the mineral owners in this survey pay under 25 cents per acre in property taxes." In the major coal counties surveyed the average tax per ton of known coal reserves is only $.0002 (1/50th of a cent).

The government-held lands are tax-exempt, but the government makes a payment in lieu of taxes, which is usually less than the normal tax rates.

"Taken together, the failure to tax minerals adequately, the underassessment of surface lands, and the revenue loss from concentrated federal holdings has a marked impact on local governments in Appalachia. The effect, essentially, is to produce a situation in which a) the small owners carry a disproportionate share of the tax burden; b) counties depend upon federal and state funds to provide revenues, while the large, corporate and absentee owners of the region's resources go relatively tax-free; and c) citizens face a poverty of needed services despite the presence in their counties of taxable property wealth, especially in the form of coal and other natural resources."

In 2013, a similar study that concentrated solely on West Virginia found that 25 private owners hold 17.6% of the state's private land of 13 million acres. The federal government owns 1,133,587 acres in West Virginia, 7.4% of the total state acreage of 15,410,560 acres. In 11 counties the top ten absentee landowners own 41% to almost 72% of the private land in each county.

In its summary the report stated that "over 55,000 parcels of property in 80 counties were studied, representing some 20,000,000 acres of land and mineral rights..." It found that "41% of the 20 million acres of land and minerals...are held by only 50 private owners and 10 government agencies. The federal government is the single largest owner in Appalachia, holding over 2,000,000 acres." The study found that the extractive industries, i.e., timber, coal, etc., were "greatly under-assessed for property tax purposes. Over 75% of the mineral owners in this survey pay under 25 cents per acre in property taxes." In the major coal counties surveyed the average tax per ton of known coal reserves is only $.0002 (1/50th of a cent).

The government-held lands are tax-exempt, but the government makes a payment in lieu of taxes, which is usually less than the normal tax rates.

"Taken together, the failure to tax minerals adequately, the underassessment of surface lands, and the revenue loss from concentrated federal holdings has a marked impact on local governments in Appalachia. The effect, essentially, is to produce a situation in which a) the small owners carry a disproportionate share of the tax burden; b) counties depend upon federal and state funds to provide revenues, while the large, corporate and absentee owners of the region's resources go relatively tax-free; and c) citizens face a poverty of needed services despite the presence in their counties of taxable property wealth, especially in the form of coal and other natural resources."

In 2013, a similar study that concentrated solely on West Virginia found that 25 private owners hold 17.6% of the state's private land of 13 million acres. The federal government owns 1,133,587 acres in West Virginia, 7.4% of the total state acreage of 15,410,560 acres. In 11 counties the top ten absentee landowners own 41% to almost 72% of the private land in each county.

Transportation has been the most challenging and expensive issue in Appalachia since the arrival of the first European settlers in the 18th century. Except the October 1, 1940, opening of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the region's mountainous terrain continuously thwarted major federal intervention attempts at major road construction until the 1970s. This left large parts of the region virtually isolated and slowing economic growth. Before the Civil War, major cities in the region were connected via wagon roads to lowland areas, and flatboats provided an important means for transporting goods out of the region. By 1900, railroads connected most of the region with the rest of the nation, although the poor roads made travel beyond railroad hubs difficult. When the Appalachian Regional Commission was created in 1965, road construction was considered its most important initiative, and in subsequent decades the commission spent more on road construction than all other projects combined.Burton, Mark, and Richard Hatcher, Introduction to Transportation section, ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 685–90.

The effort to connect Appalachia with the outside world has required numerous civil engineering feats. Millions of tons of rock were removed to build road segments such as Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River (Tennessee – North Carolina), Pigeon River Gorge at the Tennessee-North Carolina state line and U.S. Route 23 in Letcher County, Kentucky. Large tunnels were built through mountain slopes at Cumberland Gap Tunnel, Cumberland Gap in 1996 to speed up travel along U.S. Route 25E, which acts as a regional arterial connecting Appalachia to the East Coast and the Great Lakes regions. The New River Gorge Bridge in West Virginia, completed in 1977, was the longest and is now the List of longest arch bridge spans, fourth-longest single-arch bridge in the world. The Blue Ridge Parkway's Linn Cove Viaduct, the construction of which required the assembly of 153 pre-cast segments up the slopes of Grandfather Mountain, has been designated a List of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks, historic civil engineering landmark.

Transportation has been the most challenging and expensive issue in Appalachia since the arrival of the first European settlers in the 18th century. Except the October 1, 1940, opening of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the region's mountainous terrain continuously thwarted major federal intervention attempts at major road construction until the 1970s. This left large parts of the region virtually isolated and slowing economic growth. Before the Civil War, major cities in the region were connected via wagon roads to lowland areas, and flatboats provided an important means for transporting goods out of the region. By 1900, railroads connected most of the region with the rest of the nation, although the poor roads made travel beyond railroad hubs difficult. When the Appalachian Regional Commission was created in 1965, road construction was considered its most important initiative, and in subsequent decades the commission spent more on road construction than all other projects combined.Burton, Mark, and Richard Hatcher, Introduction to Transportation section, ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 685–90.

The effort to connect Appalachia with the outside world has required numerous civil engineering feats. Millions of tons of rock were removed to build road segments such as Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River (Tennessee – North Carolina), Pigeon River Gorge at the Tennessee-North Carolina state line and U.S. Route 23 in Letcher County, Kentucky. Large tunnels were built through mountain slopes at Cumberland Gap Tunnel, Cumberland Gap in 1996 to speed up travel along U.S. Route 25E, which acts as a regional arterial connecting Appalachia to the East Coast and the Great Lakes regions. The New River Gorge Bridge in West Virginia, completed in 1977, was the longest and is now the List of longest arch bridge spans, fourth-longest single-arch bridge in the world. The Blue Ridge Parkway's Linn Cove Viaduct, the construction of which required the assembly of 153 pre-cast segments up the slopes of Grandfather Mountain, has been designated a List of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks, historic civil engineering landmark.

Depictions of Appalachia and its inhabitants in popular media are typically negative, making the region an object of humor, derision, and social concern. Ledford writes, "Always part of the mythical South, Appalachia continues to languish backstage in the American drama, still dressed, in the popular mind at least, in the garments of backwardness, violence, poverty, and hopelessness." Otto argues that comic strips ''Li'l Abner'' by Al Capp and ''Barney Google'' by Billy DeBeck, which both began in 1934, caricatured the laziness and weakness for "corn squeezin's" (

Depictions of Appalachia and its inhabitants in popular media are typically negative, making the region an object of humor, derision, and social concern. Ledford writes, "Always part of the mythical South, Appalachia continues to languish backstage in the American drama, still dressed, in the popular mind at least, in the garments of backwardness, violence, poverty, and hopelessness." Otto argues that comic strips ''Li'l Abner'' by Al Capp and ''Barney Google'' by Billy DeBeck, which both began in 1934, caricatured the laziness and weakness for "corn squeezin's" (

Coalfield Generations: Health, Mining and the Environment

''Southern Spaces'', July 16, 2008. * Drake, Richard B. ''A History of Appalachia'' (2001) * * Eller, Ronald D. ''Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880–1930'' 1982. * Ford, Thomas R. ed. ''The Southern Appalachian Region: A Survey''. (1967), includes highly detailed statistics. *

text online

* Inscoe, John C. ''Movie-Made Appalachia: History, Hollywood, and the Highland South'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2020

online review

* Lee, Tom, "Southern Appalachia's Nineteenth-Century Bright Tobacco Boom: Industrialization, Urbanization, and the Culture of Tobacco", ''Agricultural History'' 88 (Spring 2014), 175–206

online

* Lewis, Ronald L. ''Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880–1920'' (1998

online edition

* Light, Melanie and Ken Light (2006). ''Coal Hollow''. Berkeley: University of California Press. * Noe, Kenneth W. and Shannon H. Wilson, ''Civil War in Appalachia'' (1997) * Obermiller, Phillip J., Thomas E. Wagner, and E. Bruce Tucker, editors (2000). ''Appalachian Odyssey: Historical Perspectives on the Great Migration.'' Westport, CT: Praeger. * Olson, Ted (1998). ''Blue Ridge Folklife''. University Press of Mississippi. * Pudup, Mary Beth, Dwight B. Billings, and Altina L. Waller, eds. ''Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century''. (1995). * * Slap, Andrew L., (ed.) (2010). ''Reconstructing Appalachia: The Civil War's Aftermath'' Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. * Stewart, Bruce E. (ed.) (2012). ''Blood in the Hills: A History of Violence in Appalachia.'' Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. * David Walls (academic), Walls, David (1977)

"On the Naming of Appalachia"

''An Appalachian Symposium''. Edited by J. W. Williamson. Boone, NC: Appalachian State University Press. * Williams, John Alexander. ''Appalachia: A History'' (2002

online edition

* Colin Woodard, Woodard, Colin American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (2011)

Space, Place, and Appalachia

A series about real and imagined spaces and places of Appalachia and their global connections in ''Southern Spaces''.

1965 Original Congressional definition

Appalachian Center for Civic Life

at Emory and Henry College

Appalachian Center for Craft

at Tennessee Tech

Appalachian Center for the Arts

Appalachian Studies

at the University of North Carolina

Digital Library of Appalachia

Loyal Jones Appalachian Center

at Berea College

University of Kentucky Appalachian Center

{{Authority control Appalachia, Appalachian culture, . Appalachian studies, . Society of Appalachia, . Appalachian Mountains Eastern United States Hill people Regions of the Southern United States Regions of the United States Southeastern United States

geographic region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

located in the central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

in the east of North America. In the north, its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountains

The Catskill Mountains, also known as the Catskills, are a physiographic province and subrange of the larger Appalachian Mountains, located in southeastern New York. As a cultural and geographic region, the Catskills are generally defined a ...

of New York, continuing south through the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a Physiographic regions of the United States, physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Highlands range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States and extends 550 miles southwest from southern ...

and Great Smoky Mountains into northern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, with West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

near the center, being the only state entirely within the boundaries of Appalachia. In 2021, the region was home to an estimated 26.3 million people.

Since its recognition as a cultural region

In anthropology and geography, a cultural area, cultural region, cultural sphere, or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associa ...

in the late 19th century, Appalachia has been a source of enduring myths and distortions regarding the isolation, temperament, and behavior of its inhabitants. Early 20th-century writers often engaged in yellow journalism focused on sensationalistic aspects of the region's culture, such as moonshining and clan feuding, portraying the region's inhabitants as uneducated and unrefined; although these stereotypes still exist to a lesser extent today, sociological studies have since begun to dispel them.Abramson, Rudy. Introduction to ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. xix–xxv.

Appalachia is endowed with abundant natural resources, but it has long struggled economically and has been associated with poverty. In the early 20th century, large-scale logging and coal mining firms brought jobs and modern amenities to Appalachia, but by the 1960s the region had failed to capitalize on any long-term benefits from these two industries. Beginning in the 1930s, the federal government sought to alleviate poverty in the Appalachian region with a series of New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

initiatives, specifically the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The TVA was responsible for the construction of hydroelectric dams that provide a vast amount of electricity and that support programs for better farming practices, regional planning, and economic development.

In 1965, the Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a United States federal–state partnership that works with the people of Appalachia to create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life. Congress established A ...

was created to further alleviate poverty in the region, mainly by diversifying the region's economy and helping to provide better health care and educational opportunities to the region's inhabitants. By 1990, Appalachia had largely joined the economic mainstream but still lagged behind the rest of the nation in most economic indicators.

Definitions

Since Appalachia lacks definite physiographical or topographical boundaries, there has been some disagreement over what the region encompasses. The most commonly used modern definition of Appalachia is the one initially defined by the

Since Appalachia lacks definite physiographical or topographical boundaries, there has been some disagreement over what the region encompasses. The most commonly used modern definition of Appalachia is the one initially defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a United States federal–state partnership that works with the people of Appalachia to create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life. Congress established A ...

(ARC) in 1965 and expanded over subsequent decades. The region defined by the commission currently includes 420 counties and eight independent cities in 13 states, including all 55 counties in West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

, 14 counties in New York, 52 in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, 32 in Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, 3 in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, 54 in Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, 25 counties and 8 cities in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, 29 in North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, 52 in Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, 6 in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, 37 in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, 37 in Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, and 24 in Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

. When the commission was established, counties were added based on economic need, however, rather than any cultural parameters.

United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an executive department of the United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and producti ...

defined the region as consisting of 206 counties in 6 states. In 1984, Karl Raitz and Richard Ulack expanded the ARC's definition to include 445 counties in 13 states, although they removed all counties in Mississippi and added two in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. Historian John Alexander Williams, in his 2002 book ''Appalachia: A History'', distinguished between a "core" Appalachian region consisting of 164 counties in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia, and a greater region defined by the ARC.

In the ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (2006), Appalachian State University historian Howard Dorgan suggests the term "Old Appalachia" for the region's cultural boundaries, noting an academic tendency to ignore the southwestern and northeastern extremes of the ARC's pragmatic definition. The term " Greater Appalachia" was introduced by American journalist Colin Woodard in his 2011 book, '' American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America''. Sean Trende, senior elections analyst at ''RealClearPolitics

RealClearPolitics (RCP) is an American political news website and polling data aggregator. It was founded in 2000 by former options trader John McIntyre and former advertising agency account executive Tom Bevan. It features selected polit ...

'', defines "Greater Appalachia" in his 2012 book, ''The Lost Majority,'' as including both the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

region and the Upland South, following Protestant Scotch-Irish migrations to the southern and Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Upland South region includes the Ozark Plateau

The Ozarks, also known as the Ozark Mountains, Ozark Highlands or Ozark Plateau, is a physiographic region in the U.S. states of Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, as well as a small area in the southeastern corner of Kansas. The Ozarks cov ...

in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, and Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, an area which is not included in the ARC definition.

Toponymy and pronunciation

While exploring inland along the northern coast of

While exploring inland along the northern coast of Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

in 1528, the members of the Narváez expedition, including Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, found a village of indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

near present-day Tallahassee, Florida, whose name they transcribed as ''Apalchen'' or ''Apalachen'' (). The name was altered by the Spanish to ''Apalache'' ( Apalachee) and used as a name for the tribe and region spreading well inland to the north. Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition first entered Apalachee territory on June 15, 1528, and applied the name. Now spelled "Appalachian," it is the fourth oldest surviving European place-name in the U.S. After the de Soto expedition in 1540, Spanish cartographers began to apply the name of the tribe to the Appalachian Mountain range. The first cartographic appearance of ''Apalchen'' is on Diego Gutiérrez's 1562 map; the first use for the mountain range is the 1565 map by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues. Le Moyne was also the first European to apply "Apalachen" specifically to a mountain range as opposed to a village, native tribe, or a southeastern region of North America.

The name was not commonly used for the whole mountain range until the late 19th century. A competing, and often more popular, name was the " Allegheny Mountains", "Alleghenies", and even "Alleghania".

In southern U.S. dialects, the mountains are called the , and the cultural region of Appalachia is pronounced , both with a third syllable like the "la" in "latch". This pronunciation is favored in the "core" region in the central and southern parts of the Appalachian range. In northern U.S. dialects, the mountains are pronounced or . The cultural region of Appalachia is pronounced , also , all with a third syllable like "lay". The use of northern pronunciations is controversial to some in the southern region. Despite not being in Appalachia, Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail, also called the A.T., is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian Tra ...

organizations in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

popularized the occasional use of the "sh" sound for the "ch" in northern dialects in the early 20th century.

History

Early history

Native American hunter-gatherers first arrived in what is now Appalachia over 16,000 years ago. The earliest discovered site is the Meadowcroft Rockshelter inWashington County, Pennsylvania

Washington County is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 209,349. Its county seat is Washington, Pe ...

, which some scientists claim is pre- Clovis culture. Several other Archaic period (8000–1000 BC) archaeological sites have been identified in the region, such as the St. Albans site in West Virginia and the Icehouse Bottom site in Tennessee. The presence of Africans in the Appalachian Mountains dates back to the 16th century with the arrival of European colonists. Enslaved Africans were first brought to America during the 16th-century Spanish expeditions to the mountainous regions of the South. In 1526 enslaved Africans were brought to the Pee Dee River region of western North Carolina by Spanish explorer Lucas Vazquez de Ayllõn. Enslaved Africans also accompanied the expeditions of Fernando de Soto in 1540 and Juan Pardo in 1566, who both traveled through Appalachia.

The de Soto and Pardo expeditions explored the mountains of South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia, and encountered complex agrarian societies consisting of Muskogean-speaking inhabitants. De Soto indicated that much of the region west of the mountains was part of the domain of Coosa, a paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for a king or queen or the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a Chiefdom, chief-based system. This term is used occasionally ...

dom centered around a village complex in northern Georgia. By the time English explorers arrived in Appalachia in the late 17th century, the central part of the region was controlled by Algonquian tribes (namely the Shawnee), and the southern part of the region was controlled by the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

. The French based in modern-day Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

also made inroads into the northern areas of the region in modern-day New York state and Pennsylvania. By the mid-18th century the French had outposts such as Fort Duquesne and Fort Le Boeuf controlling the access points of the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

and upper Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

valleys after exploration by Celeron de Bienville. European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots—later known as " Scotch-Irish", a group mostly originating from southern Scotland and northern England, many of whom had settled in Ulster Ireland prior to migrating to America—who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from prejudice as the Scotch-Irish were looked down upon by other more powerful elements in society. Others included

European migration into Appalachia began in the 18th century. As lands in eastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia and the Carolinas filled up, immigrants began pushing further and further westward into the Appalachian Mountains. A relatively large proportion of the early backcountry immigrants were Ulster Scots—later known as " Scotch-Irish", a group mostly originating from southern Scotland and northern England, many of whom had settled in Ulster Ireland prior to migrating to America—who were seeking cheaper land and freedom from prejudice as the Scotch-Irish were looked down upon by other more powerful elements in society. Others included Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

from the Palatinate region and English settlers from the Anglo-Scottish border

The Anglo-Scottish border runs for between Marshall Meadows Bay on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west, separating Scotland and England.

The Firth of Forth was the border between the Picto- Gaelic Kingdom of Alba and the Angli ...

country. Between 1730 and 1763, immigrants trickled into western Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, and western Maryland. Thomas Walker's discovery of the Cumberland Gap in 1750 and the end of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in 1763 lured settlers deeper into the mountains, namely to upper east Tennessee, northwestern North Carolina, upstate South Carolina, and central Kentucky.

During the 18th century, enslaved Africans were brought to Appalachia by European settlers of trans-Appalachia Kentucky and the upper Blue Ridge Valley. According to the first census of 1790, more than 3,000 enslaved Africans were transported across the mountains into East Tennessee and more than 12,000 into the Kentucky mountains. Between 1790 and 1840, a series of treaties with the Cherokee and other Native American tribes opened up lands in north Georgia, north Alabama, the Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North C ...

, the Cumberland Plateau, and the Great Smoky Mountains. The last of these treaties culminated in the removal of the bulk of the Cherokee population (as well as Choctaw, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

and others) from the region via the Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

Appalachian frontier

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than

Appalachian frontiersmen have long been romanticized for their ruggedness and self-sufficiency. A typical depiction of an Appalachian pioneer involves a hunter wearing a coonskin cap and buckskin clothing, and sporting a long rifle and shoulder-strapped powder horn. Perhaps no single figure symbolizes the Appalachian pioneer more than Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (, 1734September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyo ...

, a long hunter and surveyor instrumental in the early settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee. Like Boone, Appalachian pioneers moved into areas largely separated from "civilization" by high mountain ridges and had to fend for themselves against the elements. As many of these early settlers were living on Native American lands, attacks from Native American tribes were a continuous threat until the 19th century.Caudill, Harry. ''Night Comes to the Cumberlands''

As early as the 18th century, Appalachia (then known simply as the "backcountry") began to distinguish itself from its wealthier lowland and coastal neighbors to the east. Frontiersmen often argued with lowland and tidewater elites over taxes, sometimes to the point of armed revolts such as the Regulator Movement (1767–1771) in North Carolina.Drake, Richard. ''A History of Appalachia'' (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001) In 1778, at the height of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, backwoodsmen from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and what is now Kentucky took part in George Rogers Clark's Illinois campaign. Two years later, a group of Appalachian frontiersmen known as the Overmountain Men routed British forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain after rejecting a call by the British to disarm. After the war, residents throughout the Appalachian backcountry—especially the Monongahela region in western Pennsylvania and antebellum northwestern Virginia (now the north-central part of West Virginia)—refused to pay a tax placed on whiskey by the new American government, leading to what became known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The resulting tighter federal controls in the Monongahela valley resulted in many whiskey/bourbon makers migrating via the Ohio River to Kentucky and Tennessee where the industry could flourish.

Early 19th century

In the early 19th century, the rift between theyeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

farmers of Appalachia and their wealthier lowland counterparts continued to grow, especially as the latter dominated most state legislatures. People in Appalachia began to feel slighted over what they considered unfair taxation methods and lack of state funding for improvements (especially for roads). In the northern half of the region, the lowland elites consisted largely of industrial and business interests, whereas in the parts of the region south of the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, sometimes referred to as Mason and Dixon's Line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states: Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia. It was Surveying, surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Mason ...

, the lowland elites consisted of large-scale land-owning planters. The Whig Party, formed in the 1830s, drew widespread support from disaffected Appalachians.

Tensions between the mountain counties and state governments sometimes reached the point of mountain counties threatening to break off and form separate states. In 1832, bickering between western Virginia and eastern Virginia over the state's constitution led to calls on both sides for the state's separation into two states. In 1841, Tennessee state senator (and later U.S. president) Andrew Johnson introduced legislation in the Tennessee Senate calling for the creation of a separate state in East Tennessee. The proposed state would have been known as " Frankland" and would have invited like-minded mountain counties in Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama to join it.

Proposal to rename the United States

In 1839 Washington Irving proposed to rename the United States "Alleghania" or "Appalachia" in place of "America", since the latter name belonged to Latin America too.Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

later took up the idea and considered Appalachia a much better name than America or Alleghania; he thought it better defined the United States as a distinct geographical entity, separate from the rest of the Americas, and he also thought it did honor to both Irving and the natives after whom the Appalachian Mountains had been named. At the time, however, the United States had already reached far beyond the greater Appalachian region, but the "magnificence" of Appalachia Poe considered enough to rechristen the nation with a name that would be unique to its character. However, Poe's popular influence only grew decades after his death, and so the name was never seriously considered.

U.S. Civil War

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-

By 1860, the Whig Party had disintegrated. Sentiments in northern Appalachia had shifted to the pro-abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

Republican Party. In southern Appalachia, abolitionists still constituted a radical minority, although several smaller opposition parties (most of which were both pro- Union and pro-slavery) were formed to oppose the planter-dominated Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

. As states in the southern United States moved toward secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

, a majority of southern Appalachians still supported the Union. Though with opposition by Southern Unionist, middle and southern Appalachia became components of the Confederacy.Gordon McKinney, "The Civil War". ''Encyclopedia of Appalachia'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 1579–81. In 1861, a Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

newspaper identified 161 counties in southern Appalachia—which the paper called "Alleghenia"—where Union support remained strong, and which might provide crucial support for the defeat of the Confederacy. However, many of these Unionists—especially in the mountain areas of North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama—were "conditional" Unionists in that they opposed secession but also opposed violence to prevent secession, and thus when their respective state legislatures voted to secede, some would either shift their support to the Confederacy, or flee the state. Kentucky sought to remain neutral at the outset of the conflict, opting not to supply troops to either side. After Virginia voted to secede, several mountain counties in northwestern Virginia rejected the ordinance and with the help of the Union Army established a separate state, admitted to the Union as West Virginia in 1863 (on June 20, 1863). However, half the counties included in the new state, comprising two-thirds of its territory, were secessionist and pro-Confederate.

This caused great difficulty for the Unionist state government in Wheeling, both during and after the war. A similar effort occurred in East Tennessee. Still, the initiative failed after Tennessee's governor ordered the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

to occupy the region, forcing East Tennessee's Unionists to flee to the north or go into hiding. The one exception was the so-called Free and Independent State of Scott, though it was never recognized by either the Union or the Confederacy and thus would later be invaded by Confederates.

Both central and southern Appalachia suffered tremendous violence and turmoil during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. While there were two major theaters of operation in the region—namely the Shenandoah Valley and the Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located along the Tennessee River and borders Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the south. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, it is Tennessee ...

area—much of the violence was caused by bushwhackers and guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

. The northernmost battles of the war were fought in Appalachia with the Battle of Buffington Island and the Battle of Salineville resulting from Morgan's Raid. Large numbers of livestock were killed (grazing was an important part of Appalachia's economy), and numerous farms were destroyed, pillaged, or neglected. The actions of both Union and Confederate armies left many inhabitants in the region resentful of government authority and suspicious of outsiders for decades after the war.

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

Economic boom

After the Civil War, northern Appalachia experienced an economic boom. At the same time, economies in the southern region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction. Pittsburgh as well as Knoxville grew into major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area of north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes with manufacturing booms in

After the Civil War, northern Appalachia experienced an economic boom. At the same time, economies in the southern region stagnated, especially as Southern Democrats regained control of their respective state legislatures at the end of Reconstruction. Pittsburgh as well as Knoxville grew into major industrial centers, especially regarding iron and steel production. By 1900, the Chattanooga area of north Georgia and northern Alabama had experienced similar changes with manufacturing booms in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

at the edge of the Appalachian region. Railroad construction gave the greater nation access to the vast coalfields in central Appalachia, making its economy greatly dependent on coal mining. As the nationwide demand for lumber skyrocketed, lumber firms turned to the virgin forests of southern Appalachia, using sawmill and logging railroad innovations to reach remote timber stands. The Tri-Cities area of Tennessee and Virginia and the Kanawha Valley of West Virginia became major petrochemical production centers.

Stereotypes

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw the development of various regional stereotypes. Attempts by President Rutherford B. Hayes to enforce the whiskey tax in the late 1870s led to an explosion in violence between Appalachian "moonshine

Moonshine is alcohol proof, high-proof liquor, traditionally made or distributed alcohol law, illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of distilling the alcohol (drug), alcohol at night to avoid detection. In the first decades of the ...

rs" and federal "revenuers" that lasted through the Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

period in the 1920s. The breakdown of authority and law enforcement during the Civil War may have contributed to an increase in clan feuding, which by the 1880s was reported to be a problem across most of Kentucky's Cumberland region as well as Carter County, Tennessee; Carroll County, Virginia; and Mingo and Logan counties in West Virginia. Regional writers from this period such as Mary Noailles Murfree and Horace Kephart liked to focus on such sensational aspects of mountain culture, leading readers outside the region to believe they were more widespread than in reality. In an 1899 article in ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

'', Berea College president William G. Frost attempted to redefine the inhabitants of Appalachia as "noble mountaineers"—relics of the nation's pioneer period whose isolation had left them unaffected by modern times.

Entering the 21st century, residents of Appalachia are viewed by many Americans as uneducated and unrefined, resulting in culture-based stereotyping and discrimination in many areas, including employment and housing. Such discrimination has prompted some to seek redress under prevailing federal and state civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

laws.

Feuds

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became nationally known for its violent

Appalachia, and especially Kentucky, became nationally known for its violent feud

A feud , also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially family, families or clans. Feuds begin ...

s in the remote mountain districts. They pitted the men in extended clans against each other for decades, often using assassination and arson as weapons, along with ambush

An ambush is a surprise attack carried out by people lying in wait in a concealed position. The concealed position itself or the concealed person(s) may also be called an "". Ambushes as a basic military tactics, fighting tactic of soldi ...

es, gunfights, and pre-arranged shootouts. The infamous Hatfield-McCoy Feud was the best-known of these family feuds. Some of the feuds were continuations of violent local Civil War episodes. Journalists often wrote about the violence, using stereotypes that "city folks" had developed about Appalachia; they interpreted the feuds as the natural products of profound ignorance, poverty, and isolation, and perhaps even inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely genetic distance, related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genet ...

. In reality, the leading participants were typically well-to-do local elites with networks of clients who, like the Northeast and Chicago political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

s, fought for their power over local and regional politics.

Modern Appalachia

Logging firms' rapid devastation of the forests of the Appalachians sparked a movement among conservationists to preserve what remained and allow the land to "heal". In 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act, giving the federal government authority to create national forests east of the Mississippi River and control timber harvesting. Regional writers and business interests led a movement to create national parks in the eastern United States similar to Yosemite and Yellowstone in the west, culminating in the creation of theGreat Smoky Mountains National Park

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States in the southeastern United States, southeast, with parts in North Carolina and Tennessee. The park straddles the ridgeline o ...

, Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park (often ) is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States that encompasses part of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. The park is long and narrow, with the Shenandoah River and its ...

, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway is a National Parkway and National Scenic Byway, All-American Road in the United States, noted for its scenic beauty. The parkway, which is the longest linear park in the U.S., runs for through 29 counties in Virginia and ...

in the 1930s. During the same period, New England forester Benton MacKaye led the movement to build the Appalachian Trail, stretching from Georgia to Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

.

Several significant moments of investment by the United States government into areas of science and technology were established in the mid-20th century, notably with NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, crucial with the design of Apollo program

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which Moon landing, landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo followed Project Mercury that put the first Americans in sp ...

launch vehicles and propulsion of the Space Shuttle program, and at adjacent facilities Oak Ridge National Laboratory