Apocalypse Of Peter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Apocalypse of Peter, also called the Revelation of Peter, is an

The Apocalypse of Peter, also called the Revelation of Peter, is an

The Apocalypse of Peter seems to have been written between 100 AD and 150 AD. The —the point after which the Apocalypse of Peter must have been written—is shown by its probable use of the Fourth Book of Esdras, which was written about 100 AD.. Compare Apocalypse of Peter Chapter 3 with (4 Esdras, confusingly, is chapter 3 onward of the compilation book later called 2 Esdras). The Apocalypse is quoted in Book 2 of the

The Apocalypse of Peter seems to have been written between 100 AD and 150 AD. The —the point after which the Apocalypse of Peter must have been written—is shown by its probable use of the Fourth Book of Esdras, which was written about 100 AD.. Compare Apocalypse of Peter Chapter 3 with (4 Esdras, confusingly, is chapter 3 onward of the compilation book later called 2 Esdras). The Apocalypse is quoted in Book 2 of the

Jesus joins the two parables in a detailed

One of the theological messages of the Apocalypse of Peter is generally considered clear enough: the torments of hell are meant to encourage keeping a righteous path and to warn readers and listeners away from sin, knowing the horrible fate that awaits those who stray. The work also responds to the problem of

One of the theological messages of the Apocalypse of Peter is generally considered clear enough: the torments of hell are meant to encourage keeping a righteous path and to warn readers and listeners away from sin, knowing the horrible fate that awaits those who stray. The work also responds to the problem of

See 41.1-2, 48.1, and 49.1 of the ''Prophetical Extracts'', which correspond with the Ethiopic text:

Eclogae propheticae

' (Greek text).

pages 98–112 of Beck's thesis

* (a translation of solely the Ethiopic text; available open-access) * * * *

The Apocalypse of Peter (Greek Akhmim Fragment Text)

transcribed by Mark Goodacre from Erich Klostermann's edition

HTMLPDF

"Apocalypse of Peter"

overview and bibliography by Cambry Pardee. NASSCAL: ''e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha''.

by Eileen Gardiner {{DEFAULTSORT:Apocalypse Of Peter 2nd-century Christian texts 1886 archaeological discoveries Apocryphal revelations, Peter, Apocalypse of Christian apocalyptic writings Petrine-related books Texts in Koine Greek Antilegomena Katabasis

The Apocalypse of Peter, also called the Revelation of Peter, is an

The Apocalypse of Peter, also called the Revelation of Peter, is an early Christian

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and be ...

text of the 2nd century and a work of apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. '' Apocalypse'' () is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unfolding o ...

. It is the earliest-written extant work depicting a Christian account of heaven

Heaven, or the Heavens, is a common Religious cosmology, religious cosmological or supernatural place where beings such as deity, deities, angels, souls, saints, or Veneration of the dead, venerated ancestors are said to originate, be throne, ...

and hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location or state in the afterlife in which souls are subjected to punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history sometimes depict hells as eternal destinations, such as Christianity and I ...

in detail. The Apocalypse of Peter is influenced by both Jewish apocalyptic literature and Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

of the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

. The text is extant in two diverging versions based on a lost Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

original: a shorter Greek version and a longer Ethiopic version.

The work is pseudepigraphal: it is purportedly written by the disciple Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

, but its actual author is unknown. The Apocalypse of Peter describes a divine vision experienced by Peter through the risen Jesus Christ. After the disciples inquire about signs of the Second Coming of Jesus

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christian and Islamic belief that Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his ascension to Heaven (which is said to have occurred about two thousand years ago). The ...

, the work delves into a vision of the afterlife (), and details both heavenly bliss for the righteous and infernal punishments for the damned. In particular, the punishments are graphically described in a physical sense, and loosely correspond to " an eye for an eye" (): blasphemers are hung by their tongues; liars who bear false witness have their lips cut off; callous rich people are pierced by stones while being made to go barefoot and wear filthy rags, mirroring the status of the poor in life; and so on.

The Apocalypse of Peter is not included in the standard canon of the New Testament, but is classed as part of New Testament apocrypha

The New Testament apocrypha (singular apocryphon) are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cit ...

. It is listed in the canon of the Muratorian fragment

The Muratorian fragment, also known as the Muratorian Canon (Latin: ), is a copy of perhaps the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament. The fragment, consisting of 85 lines, is a Latin manuscript bound in a roughly 8th-centur ...

, a 2nd-century list of approved books in Christianity and one of the earliest surviving proto-canons. However, the Muratorian fragment expresses some hesitation on the work, saying that some authorities would not have it read in church. While the Apocalypse of Peter influenced other Christian works in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries, it came to be considered inauthentic and declined in use. It was largely superseded by the Apocalypse of Paul, a popular 4th-century work heavily influenced by the Apocalypse of Peter that provides its own updated vision of heaven and hell. The Apocalypse of Peter is a forerunner of the same genre as the ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'' of Dante, wherein the protagonist takes a tour of the realms of the afterlife.

Authorship and date

Sibylline Oracles

The ''Sibylline Oracles'' (; sometimes called the pseudo-Sibylline Oracles) are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in a frenzied state. Fourteen b ...

(), and cited by name and quoted in Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

's ''Prophetical Extracts'' (). It also appears by name in the Muratorian fragment

The Muratorian fragment, also known as the Muratorian Canon (Latin: ), is a copy of perhaps the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament. The fragment, consisting of 85 lines, is a Latin manuscript bound in a roughly 8th-centur ...

, generally dated to the late 2nd century (). All of this implies it must have been in existence by around 150 AD, the (the date before which it must have been written).

The geographic origin of the author is unknown and remains a matter of scholarly debate. The main theories are for Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

or Egypt. Richard Bauckham argues for more precisely dating the composition to the Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD) was a major uprising by the Jews of Judaea (Roman province), Judaea against the Roman Empire, marking the final and most devastating of the Jewish–Roman wars. Led by Simon bar Kokhba, the rebels succeeded ...

(132–136), and identifies the author as a Jewish Christian

Jewish Christians were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Roman Judea during the late Second Temple period, under the Herodian tetrarchy (1st century AD). These Jews believed that Jesus was the prophesied Messiah and ...

in Roman Judea, the region affected by the revolt. As an example, the writer seems to write from a position of persecution, condemning those who caused the deaths of martyrs by their lies, and Bar Kokhba is reputed to have punished and killed Christians. This suggestion is not accepted by all; Eibert Tigchelaar wrote a rebuttal of the argument as unconvincing, as other calamities such as the Jewish revolt under Trajan (115–117) could have been the inspiration, as could forgotten local persecutions. Other scholars suggest Roman Egypt

Roman Egypt was an imperial province of the Roman Empire from 30 BC to AD 642. The province encompassed most of modern-day Egypt except for the Sinai. It was bordered by the provinces of Crete and Cyrenaica to the west and Judaea, ...

as a possible origin; Jan Bremmer suggests that Greek philosophical influence in the work points to an author or editor in more Hellenized Egypt, although perhaps working off a Palestinian text.

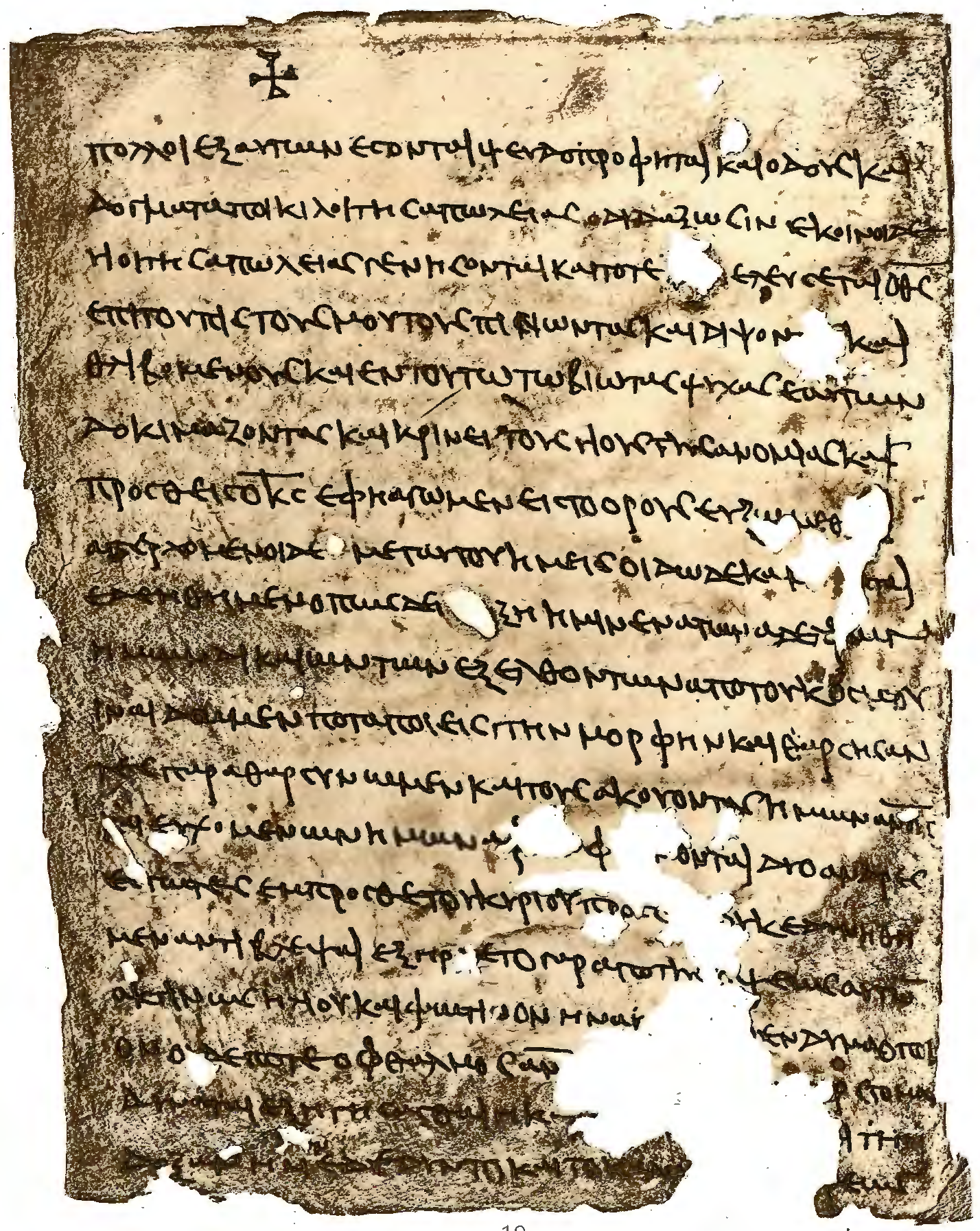

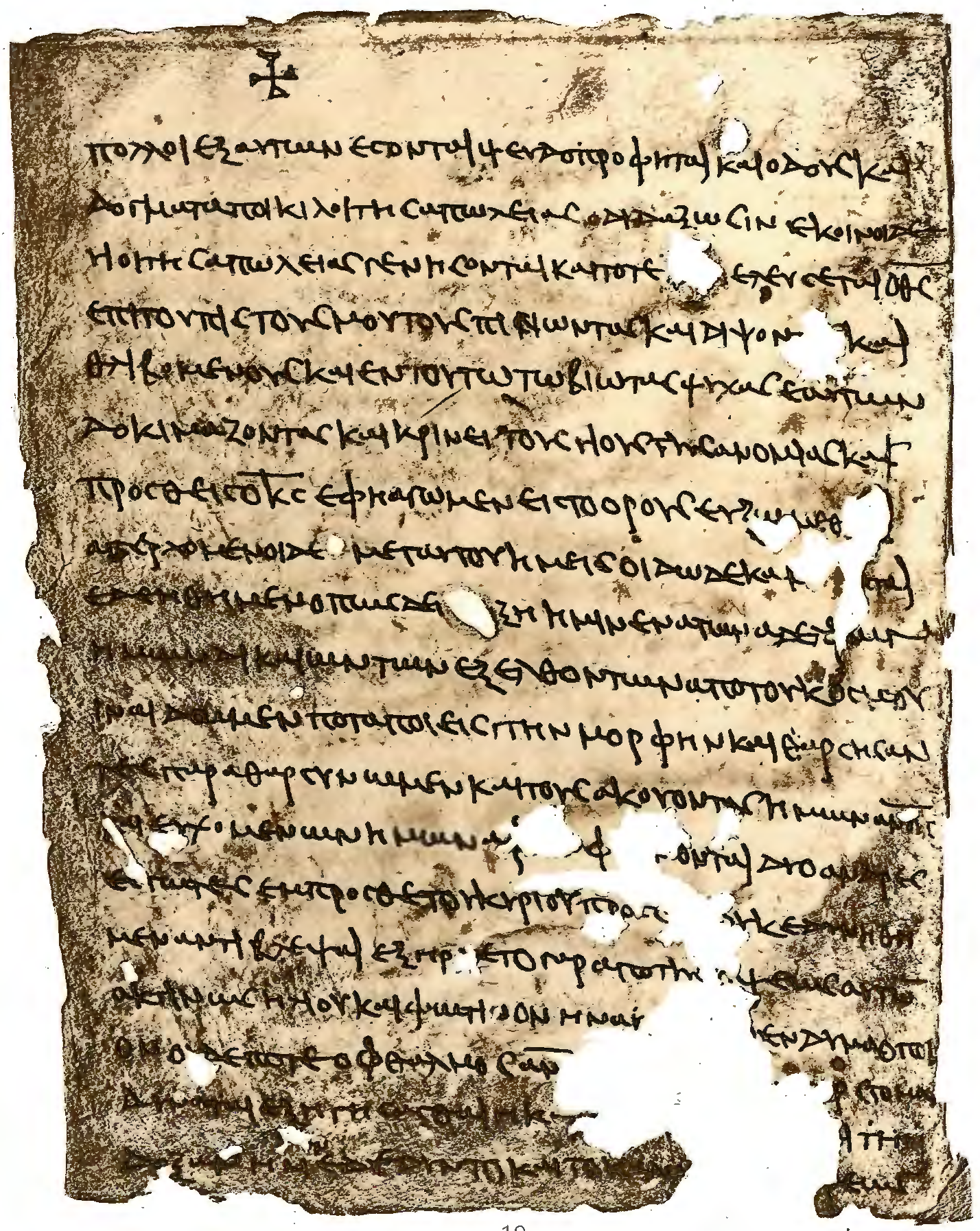

Manuscript history

From the medieval era to 1886, the Apocalypse of Peter was known only through quotations and mentions inearly Christian

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and be ...

writings. A fragmented Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

was discovered during excavations initiated by Gaston Maspéro during the 1886–87 season in a desert necropolis

A necropolis (: necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'' ().

The term usually implies a separate burial site at a distan ...

at Akhmim

Akhmim (, ; Akhmimic , ; Sahidic/Bohairic ) is a city in the Sohag Governorate of Upper Egypt. Referred to by the ancient Greeks as Khemmis or Chemmis () and Panopolis (), it is located on the east bank of the Nile, to the northeast of Sohag.

...

in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ', shortened to , , locally: ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake N ...

. The fragment consisted of parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

leaves supposedly deposited in the grave of a Christian monk. There are a wide range of estimates for when the manuscript was written. Paleographer

Palaeography ( UK) or paleography ( US) (ultimately from , , 'old', and , , 'to write') is the study and academic discipline of historical writing systems. It encompasses the historicity of manuscripts and texts, subsuming deciphering and dati ...

Guglielmo Cavallo and papyrologist

Papyrology is the study of manuscripts of ancient literature, correspondence, legal archives, etc., preserved on portable media from antiquity, the most common form of which is papyrus, the principal writing material in the ancient civilizations ...

Herwig Maehler estimate that the late 6th century is the most likely. The Greek manuscript is now kept in the Coptic Museum in Old Cairo

Old Cairo (, Egyptian pronunciation: Maṣr El-ʾAdīma) is a historic area in Cairo, Egypt, which includes the site of a Babylon Fortress, Roman-era fortress, the Christian settlement of Coptic Cairo, and the Muslim-era settlement of Fustat that ...

.

The French explorer Antoine d'Abbadie acquired a large number of manuscripts in Ethiopia in the 19th century, but many sat unanalyzed and untranslated for decades. A large set of Clementine literature

The Clementine literature (also referred to as the Clementine Romance or Pseudo-Clementine Writings) is a late antique third-century Christian romance containing an account of the conversion of Clement of Rome to Christianity, his subsequent lif ...

in Ethiopic from d'Abbadie's collection was published along with translations into French in 1907–1910. After reading the French translations, the English scholar M. R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English medievalist scholar and author who served as provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936) as well as Vice-Chancellor of the Univers ...

realized in 1910 that there was a strong correspondence with the Akhmim Greek Apocalypse of Peter, and that an Ethiopic version of the same work was within this cache.. Another independent Ethiopic manuscript was discovered on the island of Kebrān in Lake Tana

Lake Tana (; previously transcribed Tsana) is the largest lake in Ethiopia and a source of the Blue Nile. Located in Amhara Region in the north-western Ethiopian Highlands, the lake is approximately long and wide, with a maximum depth of , and ...

in 1968. Scholars speculate that these Ethiopic versions were translated from a lost Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

version, which itself was translated from the lost Greek original. The d'Abbadie manuscript is estimated by Carlo Conti Rossini to have been created in the 15th or 16th century, while the Lake Tana manuscript is estimated by Ernst Hammerschmidt to be from perhaps the 18th century.

Two other short Greek fragments of the work have been discovered, both originally found in Egypt: a 5th-century fragment held by the Bodleian library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

in Oxford that had been discovered in 1895; and the Rainer fragment held by the Rainer collection in Vienna, discovered in the 1880s but only recognized as relevant to the Apocalypse of Peter in 1929. The Rainer fragment was dated to the 3rd or 4th century by M. R. James in 1931. A 2003 analysis suggests it is from the same manuscript as the Bodleian fragment and thus also from the 5th century. These fragments offer significant variations from the other versions. In the Ethiopic manuscripts, the Apocalypse of Peter is only one section of a combined work called "The Second Coming of Christ and the Resurrection of the Dead", followed in both manuscripts by a work called "The Mystery of the Judgment of Sinners". In total, five manuscripts are extant today: the two Ethiopic manuscripts and the three Greek fragments.

Most scholars believe that the Ethiopic versions are closer to the original text, while the Greek manuscript discovered at Akhmim is a later and edited version. This is for a number of reasons: the Akhmim version is shorter, while the Ethiopic matches the claimed line count from the Stichometry of Nicephorus

The Stichometry of Nicephorus is a stichometry attributed to Patriarch Nicephorus I of Constantinople (c. 758-828). The work appears at the end of the ''Chronographikon Syntomon.'' It consists of a list of New Testament and Old Testament works c ...

; patristic

Patristics, also known as Patrology, is a branch of theological studies focused on the writings and teachings of the Church Fathers, between the 1st to 8th centuries CE. Scholars analyze texts from both orthodox and heretical authors. Patristics em ...

references and quotes seem to match the Ethiopic version better; the Ethiopic matches better with the Rainer and Bodleian Greek fragments; and the Akhmim version seems to be attempting to integrate the Apocalypse with the Gospel of Peter

The Gospel of Peter (), or the Gospel according to Peter, is an ancient text concerning Jesus Christ (title), Christ, only partially known today. Originally written in Koine Greek, it is a non-canonical gospel and was rejected as apocryphal by the ...

(also in the Akhmim manuscript), which would naturally result in revisions. Translation from Ethiopic to German was by Hugo Duensing, with David Hill and R. McL. Wilson translating the German to English. The Rainer and Bodleian fragments can be compared to the others in only a few passages, but are considered to be the most reliable guide to the original text.

Contents

The Apocalypse of Peter is framed as a discourse of Jesus to his faithful. In the Ethiopic version, the apostlePeter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

experiences a vision of hell followed by a vision of heaven, granted by the risen Christ; in the Akhmim fragment, the order of heaven and hell is reversed, and it is revealed by Jesus during his life and ministry. In the form of a Greek or , it goes into elaborate detail about the punishment in hell for each type of crime, as well as briefly sketching the nature of heaven.

The Second Coming

In the opening, the disciples ask for signs of theSecond Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christianity, Christian and Islam, Islamic belief that Jesus, Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his Ascension of Jesus, ascension to Heaven (Christianity), Heav ...

() while on the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet (; ; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also , , 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge in East Jerusalem, east of and adjacent to Old City of Jerusalem, Jerusalem's Old City. It is named for the olive, olive ...

. In chapter 2 of the Ethiopic version, Peter asks for an explanation of the meaning of the parable

A parable is a succinct, didactic story, in prose or verse, that illustrates one or more instructive lessons or principles. It differs from a fable in that fables employ animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature as characters, whe ...

s of the budding fig tree and the barren fig tree, in an expansion of the "Little Apocalypse" of Matthew 24.See Figs in the Bible for the New Testament's treatment of figs. The argument that Matthew was the writer's source is that the Apocalypse of Peter shows correspondences with the Matthean text that do not appear in the parallel passages in the synoptic gospels of Mark and Luke.Jesus joins the two parables in a detailed

allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

. The setting "in the summer" is transferred to "the end of the world"; the fig tree represents Israel, and the flourishing shoots are Jews who have adopted Jesus as Messiah and achieve martyrdom.. The work continues on to describe the end times that will accompany the Second Coming: fire and darkness will convulse the world, a crowned Christ will return in glory, and the people of the nations will pass through a river of fire. The elect will be unscathed by the test, but sinners will be brought to a place where they shall be punished for their transgressions.

Punishments and rewards

The work proceeds to describe the punishments that await the wicked. Many of the punishments are overseen by Ezrael the Angel of Wrath (most likely the angel Azrael, although possibly a corrupt reference to the angelSariel

Sariel (Hebrew and Aramaic: שָׂרִיאֵל ''Śārīʾēl'', "God is my Ruler"; Greek: Σαριηλ ''Sariēl'', ''Souriēl''; Amharic: ሰራቁያል ''Säraquyael'', ሰረቃኤል ''Säräqael'') is an angel mainly from Judaic tradi ...

). The angel Uriel

Uriel , Auriel ( ''ʾŪrīʾēl'', " El/God is my Flame"; ''Oúriḗl''; ''Ouriēl''; ; Geʽez and Amharic: or ) or Oriel ( ''ʾÓrīʾēl'', "El/God is my Light") is the name of one of the archangels who is mentioned in Rabbinic tradition ...

resurrects the dead into new bodies so that they can be either rewarded or tormented physically. Punishments in hell according to the vision include:

The vision of heaven is shorter than the depiction of hell, and described more fully in the Akhmim version. In heaven, people have pure milky white skin, curly hair, and are generally beautiful. The earth blooms with everlasting flowers and spices. People wear shiny clothes made of light, like the angels. Everyone sings in choral prayer.

In the Ethiopic version, the account closes with an account of the ascension of Jesus

The Ascension of Jesus (anglicized from the Vulgate ) is the Christianity, Christian and Islamic belief that Jesus entering heaven alive, ascended to Heaven. Christian doctrine, as reflected in the major Christian creeds and confessional stateme ...

on the mountain in chapters 15–17. Jesus, accompanied by the prophets Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

and Elijah

Elijah ( ) or Elias was a prophet and miracle worker who lived in the northern kingdom of Israel during the reign of King Ahab (9th century BC), according to the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible.

In 1 Kings 18, Elijah defended the worsh ...

, ascends on a cloud to the first heaven, and then they depart to the second heaven. While it is an account of the ascension, it includes some parallels to Matthew's account of the transfiguration of Jesus

The Transfiguration of Jesus is an event described in the New Testament where Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is Transfiguration (religion), transfigured and becomes radiant in Glory (religion), glory upon a mountain. The Synoptic Gospels (, , ) r ...

. In the Akhmim fragment, which is set when Jesus was still alive, both the mountain and the two other men are unnamed (rather than being Moses and Elijah), but the men are similarly transfigured into radiant forms.

Prayers for those in hell

One theological issue appears only in the version of the text in the Rainer fragment. Its chapter 14 describes the salvation of condemned sinners for whom the righteous pray: While not found in later manuscripts, this reading was likely original to the text, as it agrees with a quotation in the Sibylline Oracles:. Other pieces of Christian literature with parallel passages probably influenced by this include the Epistle of the Apostles and the Coptic Apocalypse of Elijah. The passage also makes literary sense, as it is a follow-up to a passage in chapter 3 where Jesus initially rebukes Peter who expresses horror at the suffering in hell; Richard Bauckham suggests that this is because it must be the victims who were harmed that request mercy, not Peter. While not directly endorsinguniversal salvation

Christian universalism is a school of Christian theology focused around the doctrine of universal reconciliation – the view that all human beings will ultimately be Salvation in Christianity, saved and restored to a right God#Relationship with ...

, it does suggest that salvation will eventually reach as far as the compassion of the elect.

The Ethiopic manuscript maintains a version of the passage, but it differs in that it is the elect and righteous who receive baptism and salvation in a field rather than a lake ("field of Akerosya, which is called Aneslasleya" in Ethiopic), perhaps conflating Acherusia with the Elysian field. The Ethiopic version of the list of punishments in hell includes sentences not in the Akhmim fragment saying that the punishment is eternal—hypothesized by many scholars to be later additions. Despite this, the other Clementine works in the Ethiopic manuscripts discuss a great act of divine mercy to come that must be kept secret, yet will rescue some or all sinners from hell, suggesting this belief had not entirely fallen away..

Influences, genre, and related works

As the title suggests, the Apocalypse of Peter is classed as part of the genre ofapocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. '' Apocalypse'' () is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unfolding o ...

. The Greek word literally means "revelation", and apocalypses typically feature a revelation of otherworldly secrets from a divine being to a human—in the case of this work, Jesus and Peter. Like many other apocalypses, the work is pseudepigrapha

A pseudepigraph (also :wikt:anglicized, anglicized as "pseudepigraphon") is a false attribution, falsely attributed work, a text whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. Th ...

l: it claims the authorship of a famous figure to bolster the authority of its message. The Apocalypse of Peter is one of the earliest examples of a Christian , a genre of explicit depictions of the realms and fates of the dead.

Predecessors

Much of the early scholarship on the Apocalypse was spent on efforts to determine its predecessor influences. The first studies generally emphasized its roots in Hellenistic philosophy and thought. , a work by Albrecht Dieterich published in 1893 on the basis of the Akhmim manuscript alone, identified parallels and links with the Orphic religious tradition and Greek cultural context. Plato's is often held up as an example of the Greek beliefs on the nature of the afterlife that influenced the Apocalypse of Peter. Scholarship in the late 20th century by Martha Himmelfarb and others emphasizes the strong Jewish roots of the Apocalypse of Peter as well. Apocalypses were a popular genre among Jews in the era of Greek and then Roman rule. Much of the Apocalypse of Peter may be based on or influenced by these lost Jewish apocalypses, works such as the "Book of the Watchers" (chapters 1–36 of theBook of Enoch

The Book of Enoch (also 1 Enoch;

Hebrew language, Hebrew: סֵפֶר חֲנוֹךְ, ''Sēfer Ḥănōḵ''; , ) is an Second Temple Judaism, ancient Jewish Apocalyptic literature, apocalyptic religious text, ascribed by tradition to the Patriar ...

), and 1st–2nd-century Jewish thought in general. The work probably cites the Jewish apocalyptic work 4 Esdras. The author also appears to be familiar with the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells the story of who the author believes is Israel's messiah (Christ (title), Christ), Jesus, resurrection of Jesus, his res ...

but no other gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

s; a line in chapter 16 has Peter realizing the meaning of the Beatitude quote that "Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness's sake, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven.".

The Apocalypse of Peter seems to quote from Ezekiel 37, the story of the Valley of Dry Bones. During its rendition of the ascension of Jesus

The Ascension of Jesus (anglicized from the Vulgate ) is the Christianity, Christian and Islamic belief that Jesus entering heaven alive, ascended to Heaven. Christian doctrine, as reflected in the major Christian creeds and confessional stateme ...

, it also quotes from Psalm 24, which was considered as a messianic psalm foretelling the coming of Jesus and Christianity in the early church. The psalm is given an interpretation as a prophecy of Jesus's entry into heaven.

The post-mortem baptism in the Acherousian lake was likely influenced by the Jewish cultural practice of washing the dead before the corpse is buried, a practice shared by early Christians. There was a linkage or analogy between cleansing the soul on death as well as cleaning the body, as the Apocalypse of Peter passage essentially combines the two.

While much work has been done on predecessor influences, Eric Beck stresses that much of the Apocalypse of Peter is distinct among extant literature of the period, and may well have been unique at the time, rather than simply adapting lost earlier writings. As an example, earlier Jewish literature varied in its depictions of Sheol

Sheol ( ; ''Šəʾōl'', Tiberian: ''Šŏʾōl'') in the Hebrew Bible is the underworld place of stillness and darkness which is death.

Within the Hebrew Bible, there are few—often brief and nondescript—mentions of Sheol, seemingly descri ...

, the underworld, but did not usually threaten active torment to the wicked. Instead eternal destruction was the more frequent threat in these early works, a possibility that does not arise in the Apocalypse of Peter.

Contemporary work

In the beginning of the book, Jesus, who had been resurrected, is giving further insights to the Apostles. This is followed by an account of Jesus's ascension. This appears to have been a popular setting in 2nd century Christian works, with the dialogue generally taking place on a mountain, as in the Apocalypse of Peter. The genre is sometimes called a "dialogue Gospel", and is seen in works such as the Epistle of the Apostles, the Questions of Bartholomew, and various Gnostic works such as the . Among writings that were eventually canonized in the New Testament, the Apocalypse of Peter shows a close resemblance in ideas with the epistle2 Peter

2 Peter, also known as the Second Epistle of Peter and abbreviated as 2 Pet., is an epistle of the New Testament written in Koine Greek. It identifies the author as "Simon Peter" (in some translations, 'Simeon' or 'Shimon'), a bondservant and ...

, to the extent that many scholars believe one had copied passages from the other due to the number of close parallels. While both the Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of John (the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

) are apocalypses in genre, the Revelation of Peter puts far more stress on the afterlife and divine rewards and punishments, while the Revelation of John focuses on a cosmic battle between good and evil.

Later influence

The Apocalypse of Peter is the earliest surviving detailed depiction of heaven and hell in a Christian context. These depictions appear to have been quite influential to later works, although how much of this is due to the Apocalypse of Peter itself and how much to lost similar literature is unclear. TheSibylline Oracles

The ''Sibylline Oracles'' (; sometimes called the pseudo-Sibylline Oracles) are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in a frenzied state. Fourteen b ...

, popular among Roman Christians, directly quotes the Apocalypse of Peter. Macarius Magnes

Macarius Magnes (), sometimes referred to as Macarius of Magnesia, is the author of a work of Christian apologetics contesting the writings of a Neo-Platonic philosopher. He was unknown for centuries until the discovery of a manuscript at Athens ...

's , a 3rd-century Christian apologetic work, features "a pagan philosopher" who quotes the Apocalypse of Peter, albeit in an attempt to disprove Christianity. The visions narrated in the Acts of Thomas

''Acts of Thomas'' is an early 3rd-century text, one of the New Testament apocrypha within the Acts of the Apostles subgenre. The complete versions that survive are Syriac and Greek. There are many surviving fragments of the text. Scholars d ...

, another 3rd-century work, also appear to quote or reference the Apocalypse of Peter. The bishop Methodius of Olympus

Methodius of Olympus () (died c. 311) was an early Christian bishop, ecclesiastical author, and martyr. Today, he is honored as a saint and Church Father; the Catholic Church commemorates his feast on June 20.

Life

Few reports have survived on ...

appears to positively quote the Apocalypse of Peter in the 4th century, although it is uncertain whether he regarded it as scripture.

The Apocalypse of Peter is a predecessor of and has similarities with the genre of Clementine literature

The Clementine literature (also referred to as the Clementine Romance or Pseudo-Clementine Writings) is a late antique third-century Christian romance containing an account of the conversion of Clement of Rome to Christianity, his subsequent lif ...

that would later be popular in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, although Clement himself does not appear in the Apocalypse of Peter. Clementine stories usually involved Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

and Clement of Rome

Clement of Rome (; ; died ), also known as Pope Clement I, was the Pope, Bishop of Rome in the Christianity in the 1st century, late first century AD. He is considered to be the first of the Apostolic Fathers of the Church.

Little is known about ...

having adventures, revelations, and dialogues together. Both Ethiopic manuscripts that include the Apocalypse of Peter are mixed in with other Ethiopic Clementine literature that feature Peter prominently. Clementine literature became popular in the third and fourth century, but it is not known when the Clementine sections of the Ethiopic manuscripts containing the Apocalypse of Peter were originally written. Daniel Maier proposes an Egyptian origin in the 6th–10th centuries, while Richard Bauckham suggests the author was familiar with the Arabic Apocalypse of Peter and proposes an origin in the 8th century or later.

Later apocalyptic works inspired by the Apocalypse of Peter include the Apocalypse of Thomas in the 2nd–4th century, and more influentially, the Apocalypse of Paul in the 4th century. One change that the Apocalypse of Paul makes is describing personal judgments that happen immediately after death and decide whether a soul receives bliss or torment, rather than the Apocalypse of Peter being a vision of a future destiny that will take place after the Second Coming of Jesus. Hell and paradise are both on a future Earth in Peter, but are another realm of existence in Paul. The Apocalypse of Paul is also more interested in condemning sins committed by insufficiently devout Christians, while the Apocalypse of Peter seems to view the righteous as a unified group. The Apocalypse of Paul never saw official Church approval. Despite this, it would go on to be popular and influential for centuries, possibly due to the high esteem in which it was held among medieval monks. Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'' would become extremely popular and celebrated in the 14th century and beyond, and was influenced by the Apocalypse of Paul. The Apocalypse of Peter thus was the forerunner of these influential visions of the afterlife: Emiliano Fiori wrote that it contains the "embryonic forms" of the heaven and hell of the Apocalypse of Paul, and Jan Bremmer wrote that the Apocalypse of Paul was "the most important step in the direction that would find its apogee in Dante".

Analysis

The punishments and ''lex talionis''

The list of punishments for the damned is likely the most influential and famous part of the work, with almost two-thirds of the text dedicated to the calamitous end times that will accompany the return of Jesus (Chapters 4–6) and the punishments afterward (Chapters 7–13)... The punishments in the vision generally correspond to the past sinful actions, usually with a correspondence between the body part that sinned and the body part that is tortured. It is a loose version of the Jewish notion of aneye for an eye

"An eye for an eye" (, ) is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The earliest known use of the principle appears in the Code of Hammurabi, which predates the wr ...

, also known as , that the punishment should fit the crime. The phrase "each according to his deed" appears five times in the Ethiopic version to explain the punishments.. Dennis Buchholz writes that the verse "Everyone according to his deeds" is the theme of the entire work. In a dialogue with the angel Tatirokos, the keeper of Tartarus

In Greek mythology, Tartarus (; ) is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato's '' Gorgias'' (), souls are judged after ...

, the damned themselves admit that their fate is based on their own deeds, and is fair and just.. The role reversal seen in the punishment of the wealthy who neglected poor widows and orphans is perhaps the most direct example, with them wearing filthy rags: they suffer exactly as they let others suffer.. Still, the connection between the crime and the punishment is not always obvious. David Fiensy writes that "It is possible that where there is no logical correspondence, the punishment has come from the Orphic tradition and has simply been clumsily attached to a vice by a Jewish redactor."

Bart Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born October 5, 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books ...

contests classifying the ethics of the Apocalypse as being those of , and considers bodily correspondence the overriding concern instead. For Ehrman, the punishments described are far more severe than the original crime – which goes against the idea of punishments being commensurate to the damage inflicted within "an eye for an eye"..

Callie Callon suggests a philosophy of "mirror punishment" as motivating the punishments where the harm done is reflected in a sort of poetic justice

Poetic justice, also called poetic irony, is a literary device with which ultimately virtue is rewarded and misdeeds are punished. In modern literature, it is often accompanied by an ironic twist of fate related to the character's own action, h ...

, and is determined more by symbolism than by the . She argues that this best explains the logic behind placing sorcerers in a wheel of fire

In a literary context, a wheel of fire may refer to the chain of tortuous or dire consequences that result from a single action.

In mythology

The Wheel of Fire originates in Greek mythology as the punishment for Ixion, who was bound to a wheel ...

, considered unclear by scholars such as Fiensy. Other scholars have suggested that it is perhaps a weak reference to the punishment of Ixion

In Greek mythology, Ixion ( ; ) was king of the Lapiths, the most ancient tribe of Thessaly.

Family

Ixion was the son of Ares, or Leonteus (mythology), Leonteus, or Antion and Perimele, or the notorious evildoer Phlegyas, whose name connotes " ...

in Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

; Callon suggests that it is, instead, a reference to a rhombus

In plane Euclidean geometry, a rhombus (: rhombi or rhombuses) is a quadrilateral whose four sides all have the same length. Another name is equilateral quadrilateral, since equilateral means that all of its sides are equal in length. The rhom ...

, a spinning top that was also used by magicians. The magicians had spun a rhombus for power in their lives, and now were tormented by similar spinning, with the usual addition of fire seen in other punishments.

The text is somewhat corrupt and unclear in Chapter 11, known only from the Ethiopic version, which describes the punishment for those who dishonor their parents. The nature of the first punishment is hard to discern and involves going up to a high fiery place, perhaps a volcano. It is believed by most translators that the target was closer to "adults who abandon their elderly parents" rather than condemning disobedient children, but it is difficult to be certain. However, the next punishments do target children, saying that those who fail to heed tradition and their elders will be devoured by birds, while girls who do not maintain their virginity before marriage (implicitly also a violation of parental expectations) will have their flesh torn apart. This is possibly an instance of mirror punishment or bodily correspondence, where the skin which sinned is itself punished. The text also specifies ten girls are punished – possibly a loose reference to the Parable of the Ten Virgins in the Gospel of Matthew, although not a very accurate one if so, as only five virgins are reprimanded in the parable, and for unrelated reasons.

The Apocalypse of Peter is one of the earliest pieces of Christian literature to feature an anti-abortion

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its Abortion by country, legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in r ...

message; mothers who abort their children are among those tormented.

Christology

The Akhmim Greek text generally refers to Jesus as , "Lord". The Ethiopic manuscripts are similar, but the style notably shifts in Chapters 15 and 16 in the last section of the work, which refer to Jesus by name and introduce him with exalted titles including "Jesus Christ our King" (''negus

''Negus'' is the word for "king" in the Ethiopian Semitic languages and a Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, title which was usually bestowed upon a regional ruler by the Ethiopian Emperor, Negusa Nagast, or "king of kings," in pre-1974 Et ...

'') and "my God Jesus Christ". This is considered a sign this section was edited later by a scribe with a high Christology.

Angels and demons

It is unknown how much of theangelology

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in various ...

and demonology

Demonology is the study of demons within religious belief and myth. Depending on context, it can refer to studies within theology, religious doctrine, or occultism. In many faiths, it concerns the study of a hierarchy of demons. Demons may be n ...

in the Ethiopic version was in the older Greek versions. The Akhmim version does not mention demons when describing the punishment of those who forsook God's commandments; even in Ethiopic, it is possible that the demons are servants of God performing the punishment, rather than those who led the damned into sin. As the Ethiopic version was likely a translation of an Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

translation, it may have picked up some influence from Islam centuries later; the references to Ezrael the Angel of Wrath were possibly influenced by Azrael the Angel of Death, who is usually more associated with Islamic angelology. The Ethiopic version does make it clear that punishments are envisioned not just for human sin, but also supernatural evil: the angel Uriel

Uriel , Auriel ( ''ʾŪrīʾēl'', " El/God is my Flame"; ''Oúriḗl''; ''Ouriēl''; ; Geʽez and Amharic: or ) or Oriel ( ''ʾÓrīʾēl'', "El/God is my Light") is the name of one of the archangels who is mentioned in Rabbinic tradition ...

gives physical bodies to the evil spirits that inhabited idols and led people astray so that they, too, can be burned in the fire and punished. Sinners who perished in the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeva ...

are brought back as well: probably a reference to the Nephilim

The Nephilim (; ''Nəfīlīm'') are mysterious beings or humans in the Bible traditionally understood as being of great size and strength, or alternatively beings of great power and authority. The origins of the Nephilim are disputed. Some, ...

, the children of the Watchers (fallen angels) and mortal women described in the Book of Enoch

The Book of Enoch (also 1 Enoch;

Hebrew language, Hebrew: סֵפֶר חֲנוֹךְ, ''Sēfer Ḥănōḵ''; , ) is an Second Temple Judaism, ancient Jewish Apocalyptic literature, apocalyptic religious text, ascribed by tradition to the Patriar ...

and the Book of Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees is an ancient Jewish apocryphal text of 50 chapters (1,341 verses), considered canonical by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, as well as by Haymanot Judaism, a denomination observed by members of Ethiopian Jewish ...

.

The children who died by infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of re ...

are delivered to the angel "Temelouchus", which probably was a rare Greek word meaning "care-taking ne. Later writers seem to have interpreted it as a proper name, however, resulting in a specific angel of hell appearing named "Temlakos" (Ethiopic) or " Temeluchus" (Greek), found in the Apocalypse of Paul and various other sources.

Literary merits

Scholars of the 19th and 20th century considered the work rather intellectually simple and naive; dramatic and gripping, but not necessarily a coherent story. Still, the Apocalypse of Peter was popular and had a wide audience in its time.M. R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English medievalist scholar and author who served as provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936) as well as Vice-Chancellor of the Univers ...

remarked that his impression was that educated Christians of the later Roman period considered the work somewhat embarrassing and "realized it was a gross and vulgar book", which might have partially explained a lack of elite enthusiasm for canonizing it later.

Theology

One of the theological messages of the Apocalypse of Peter is generally considered clear enough: the torments of hell are meant to encourage keeping a righteous path and to warn readers and listeners away from sin, knowing the horrible fate that awaits those who stray. The work also responds to the problem of

One of the theological messages of the Apocalypse of Peter is generally considered clear enough: the torments of hell are meant to encourage keeping a righteous path and to warn readers and listeners away from sin, knowing the horrible fate that awaits those who stray. The work also responds to the problem of theodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

addressed in earlier writings such as Daniel: the question of why a sovereign and just God allows the persecution of the righteous on Earth. The Apocalypse says that everyone will be repaid by their deeds, even the dead, and God will eventually make things right. Scholars have come up with different interpretations of the intended tone of the work. Michael Gilmour sees the work as encouraging schadenfreude

Schadenfreude (; ; "harm-joy") is the experience of pleasure, joy, or self-satisfaction that comes from learning of or witnessing the troubles, failures, pain, suffering, or humiliation of another. It is a loanword from German. Schadenfreude ...

and delighting in the suffering of the wicked, while Eric Beck argues the reverse: that the work was intended to ultimately cultivate compassion for those suffering, including the wicked and even persecutors. Most scholars agree that the Apocalypse simultaneously advocates for both divine justice and divine mercy, and contains elements of both messages.

The version of the Apocalypse seen in the Ethiopic version could plausibly have originated from a Christian community that still considered itself as part of Judaism. The adaptation of the fig tree parables to an allegory about the flourishing of Israel and its martyrs pleasing God is only found in Chapter 2 of the Ethiopic version. While it is impossible to know for sure why it is absent in the Greek Akhmim version, one possibility is that it was edited out due to incipient anti-Jewish sentiment in the church. A depiction of Jews converting and Israel being especially blessed may have fit poorly with the strong repudiation of Judaism common in the Church during the 4th and 5th centuries.

In one passage in Chapter 16, Peter offers to build three tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle (), also known as the Tent of the Congregation (, also Tent of Meeting), was the portable earthly dwelling of God used by the Israelites from the Exodus until the conquest of Canaan. Moses was instru ...

s on Earth. Jesus sharply rebukes him, saying that there is only a single heavenly tabernacle. This is possibly a reference to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD and a condemnation of attempting to build a replacement "Third Temple

The "Third Temple" (, , ) refers to a hypothetical rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem. It would succeed the First Temple and the Second Temple, the former having been destroyed during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in and the latter having bee ...

", although perhaps it is only a reference to all of God's elect living together with a unified tabernacle in Paradise.

Debate over canonicity

The Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately not included in theNew Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

, but appears to have been one of the works that came closest to being included, along with ''The Shepherd of Hermas

''The Shepherd of Hermas'' (; ), sometimes just called ''The Shepherd'', is a Christian literary work of the late first half of the second century, considered a valuable book by many Christians, and considered canonical scripture by some of the ...

''. The Muratorian fragment

The Muratorian fragment, also known as the Muratorian Canon (Latin: ), is a copy of perhaps the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament. The fragment, consisting of 85 lines, is a Latin manuscript bound in a roughly 8th-centur ...

is one of the earliest-created extant lists of approved Christian sacred writings, part of the process of creating what would eventually be called the New Testament. The fragment is generally dated to the late 2nd century (). It gives a list of works read in the Christian churches that is similar to the modern accepted canon; however, it does not include some of the general epistles, but does include the Apocalypse of Peter. The Muratorian fragment states: "We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in the church." (Other pieces of apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. '' Apocalypse'' () is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unfolding o ...

are implicitly acknowledged, yet not "received".) Both the Apocalypse of Peter and the Apocalypse of John (the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

) appear to have been controversial, with some churches of the 2nd and 3rd centuries using them and others not. A common criticism of those who opposed the canonicity of these works was to accuse them of lacking apostolic authorship.

Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

appears to have considered the Apocalypse of Peter to be holy scripture ()..See 41.1-2, 48.1, and 49.1 of the ''Prophetical Extracts'', which correspond with the Ethiopic text:

Eclogae propheticae

' (Greek text).

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

personally classified the work as inauthentic and spurious, yet not heretical, in his book ''Church History

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual side of t ...

'' (). Eusebius also describes a lost work of Clement's, the (Outlines), that gave "abbreviated discussions of the whole of the registered divine writings, without passing over the disputed ritings– I mean Jude and the rest of the general letters, and the Letter of Barnabas, and the so-called Apocalypse of Peter." The Apocalypse of Peter is listed in the catalog of the 6th-century Codex Claromontanus

Codex Claromontanus, symbolized by Dp, D2 or 06 (in the Biblical manuscript#Gregory-Aland, Gregory-Aland numbering), δ 1026 (Biblical manuscript#Von Soden, von Soden), is a Greek-Latin diglot uncial manuscript of the New Testament, written in an ...

, which was probably copying a 3rd- or 4th-century source. The entry in the catalog is marked with an obelus

An obelus (plural: obeluses or obeli) is a term in codicology and latterly in typography that refers to a historical annotation mark which has resolved to three modern meanings:

* Division sign

* Dagger

* Commercial minus sign (limited g ...

(along with the Epistle of Barnabas, ''The Shepherd of Hermas'', and the Acts of Paul

The Acts of Paul is one of the major works and earliest pseudepigraphal series from the New Testament apocrypha also known as Acts of the Apostles (genre), Apocryphal Acts. This work is part of a body of literature either about or purporting to ...

): probably an indication by the scribe that its status was not authoritative. As late as the 5th century, Sozomen

Salamanes Hermias Sozomenos (; ; c. 400 – c. 450 AD), also known as Sozomen, was a Roman lawyer and historian of the Christian Church.

Family and home

Sozoman was born around 400 in Bethelia, a small town near Gaza, into a wealthy Christia ...

indicates that some churches in Palestine still read it, but by then, it seems to have been considered inauthentic by most Christians. The Byzantine-era Stichometry of Nicephorus

The Stichometry of Nicephorus is a stichometry attributed to Patriarch Nicephorus I of Constantinople (c. 758-828). The work appears at the end of the ''Chronographikon Syntomon.'' It consists of a list of New Testament and Old Testament works c ...

lists both the Apocalypses of Peter and John as used if disputed books.

Although these references to it attest that it was in wide circulation in the 2nd and 3rd century, the Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately not accepted into the Christian biblical canon, although the reason why is not entirely clear. One hypothesis for why the Apocalypse of Peter failed to gain enough support to be canonized is that its view on the afterlife was too close to endorsing Christian universalism and the related doctrine of , that God will make all things perfect in the fullness of time. The passage in the Rainer fragment that the saints, seeing the torment of sinners from heaven, could ask God for mercy, and these damned souls could be retroactively baptized and saved, had significant theological implications. Presumably, all of hell could eventually be emptied in such a manner. M. R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English medievalist scholar and author who served as provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936) as well as Vice-Chancellor of the Univers ...

argued that the original Apocalypse of Peter may well have suggested universal salvation

Christian universalism is a school of Christian theology focused around the doctrine of universal reconciliation – the view that all human beings will ultimately be Salvation in Christianity, saved and restored to a right God#Relationship with ...

after a period of cleansing suffering in hell. This ran against the stance of many Church theologians of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries who strongly felt that salvation and damnation were eternal and strictly based on actions and beliefs while alive. Augustine of Hippo, in his work ''The City of God'', denounces arguments based on very similar logic to what is seen in the Rainer passage. Such a system, where saints could at least pray their friends and family out of hell, and possibly any damned soul, would have been considered incorrect at best, and heretical at worst. Most scholars since agree with James: the reading in the Rainer fragment was that of the original. The contested passage was not copied by later scribes who felt it was in error, hence not appearing in later manuscripts, along with the addition of the sentences indicating the punishment would be eternal. Bart Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born October 5, 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books ...

suggests that the damage to the book's reputation was already done, however. The Origenist Controversies of the 4th and 5th centuries retroactively condemned much of the thought of the theologian Origen, particularly his belief in universal salvation, and this anti-Origen movement was at least part of why the book was not included in the biblical canons of later centuries.

Translations

Selected modern English translations of the Apocalypse of Peter can be found in: * (a composite translation drawing from both the Greek and the Ethiopic; available openly apages 98–112 of Beck's thesis

* (a translation of solely the Ethiopic text; available open-access) * * * *

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

* , translation byM. R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English medievalist scholar and author who served as provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936) as well as Vice-Chancellor of the Univers ...

in the 1924 book ''The Apocryphal New Testament'', with quotations from the Sibylline Oracles and writings of the early Church

The Apocalypse of Peter (Greek Akhmim Fragment Text)

transcribed by Mark Goodacre from Erich Klostermann's edition

HTML

"Apocalypse of Peter"

overview and bibliography by Cambry Pardee. NASSCAL: ''e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha''.

by Eileen Gardiner {{DEFAULTSORT:Apocalypse Of Peter 2nd-century Christian texts 1886 archaeological discoveries Apocryphal revelations, Peter, Apocalypse of Christian apocalyptic writings Petrine-related books Texts in Koine Greek Antilegomena Katabasis