Antitheatricality is any form of opposition or hostility to

theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communi ...

. Such opposition is as old as theater itself, suggesting a deep-seated ambivalence in human nature about the dramatic arts. Jonas Barish's 1981 book, ''The Antitheatrical Prejudice'', was, according to one of his

Berkeley colleagues, immediately recognized as having given intellectual and historical definition to a phenomenon which up to that point had been only dimly observed and understood. The book earned the American Theater Association's Barnard Hewitt Award for outstanding research in theater history. Barish and some more recent commentators treat the anti-theatrical, not as an enemy to be overcome, but rather as an inevitable and valuable part of the theatrical dynamic.

Antitheatrical views have been based on philosophy, religion, morality, psychology, aesthetics and on simple prejudice. Opinions have focussed variously on the art form, the artistic content, the players, the lifestyle of theater people, and on the influence of theater on the behaviour and morals of individuals and society. Anti-theatrical sentiments have been expressed by government legislation, philosophers, artists, playwrights, religious representatives, communities, classes, and individuals.

The earliest documented objections to theatrical performance were made by Plato around 380 B.C. and re-emerged in various forms over the following 2,500 years. Plato's philosophical objection was that theatrical performance was inherently distanced from reality and therefore unworthy. Church leaders would rework this argument in a theological context. A later aesthetic variation, which led to closet drama, valued the play, but only as a book. From Victorian times, critics complained that self-aggrandizing actors and lavish stage settings were getting in the way of the play.

Plato's moral objections were echoed widely in Roman times, leading eventually to theater's decline. During the Middle Ages, theatrical performance gradually re-emerged, the mystery plays accepted as part of church life. From the 16th century onwards, once theater was re-established as an independent profession, concerns were regularly raised that the acting community was inherently corrupt and that acting had a destructive moral influence on both actors and audiences. These views were often expressed during the emergence of Protestant, Puritan and Evangelical movements.

Plato and ancient Greece

Athens

Around 400 B.C. the importance of

Greek drama to

ancient Greek culture

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically rel ...

was expressed by

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Ancient Greek comedy, comic playwright from Classical Athens, Athens. He wrote in total forty plays, of which eleven survive virtually complete today. The majority of his surviving play ...

in his play, ''

The Frogs

''The Frogs'' (; , often abbreviated ''Ran.'' or ''Ra.'') is a comedy written by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It was performed at the Lenaia, one of the Festivals of Dionysus in Athens, in 405 BC and received first place.

The pla ...

,'' where the chorus leader says, "There is no function more noble than that of the god-touched Chorus teaching the city in song". Theater and religious festivals were intimately connected.

Around 380 B.C.

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

became the first to challenge theater in the ancient world. Although his views expressed in

''The Republic'' were radical, they were aimed primarily at the concept of theater (and other mimetic arts). He did not encourage hostility towards the artists or their performances. For Plato, theater was philosophically undesirable, it was simply a lie. It was bad for society because it engaged the sympathies of the audience and so might make people less thoughtful. Furthermore, the representation of ignoble actions on the stage could lead the actors and the audience to behave badly themselves.

Mimesis

Philosophically, acting is a special case of

mimesis

Mimesis (; , ''mīmēsis'') is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including '' imitatio'', imitation, similarity, receptivity, representation, mimicry, the act of expression, the act of ...

(μίμησις), which is the correspondence of art to the physical world understood as a model for beauty, truth, and the good. Plato explains this by using an illustration of an everyday object. First there is a universal truth, for example, the abstract concept of a bed. The carpenter who makes the bed creates an imperfect ''imitation'' of that concept in wood. The artist who paints a picture of the bed is making an imperfect ''imitation'' of the wooden bed. The artist is therefore several stages away from true reality and this is an undesirable state. Theater is likewise several stages from reality and therefore unworthy. The written words of a play can be considered more worthy since they can be understood directly by the mind and without the inevitable distortion caused by intermediaries.

Psychologically, mimesis is considered as formative, shaping the mind and causing the actor to become more like the person or object imitated. Actors should therefore only imitate people very much like themselves and then only when aspiring to virtue and avoiding anything base. Furthermore, they must not imitate women, or slaves, or villains, or madmen, or 'smiths or other artificers, or oarsmen, boatswains, or the like'.

Aristotle

In ''The'' ''Poetics'' (Περὶ ποιητικῆς) c. 335 BC, Aristotle argues against Plato’s objections to ''mimesis'', supporting the concept of ''catharsis'' (cleansing) and affirms the human drive to imitate. Frequently, the term that Aristotle uses for ‘actor’ is ''prattontes'', suggesting ''praxis'' or real action, as opposed to Plato’s use of ''hypocrites'' (ὑποκριτής) which suggests one who 'hides under a mask', is deceptive or expresses make-believe emotions. Aristotle wants to avoid the hypothetical consequence of Plato’s critique, namely the closing of theaters and the banishment of actors. Ultimately Aristotle’s attitude is ambivalent; he concedes that drama should be able to exist without actually being acted.

Plutarch

The ''

Moralia

The ''Moralia'' (Latin for "Morals", "Customs" or "Mores"; , ''Ethiká'') is a set of essays ascribed to the 1st-century scholar Plutarch of Chaeronea. The eclectic collection contains 78 essays and transcribed speeches. They provide insigh ...

'' of

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, written in the first century, contain an essay (often given the title, ''Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?'') which reflects many of Plato's critical views but in a less nuanced way. Plutarch wonders what it tells us about the audience in that we take pleasure in watching an actor express strongly negative emotions on stage, whereas in real life, the opposite would be true.

Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity

Rome

Unlike Greece, theatre in Rome was distanced from religion and was largely led by professional actor-managers. From early days the acting profession was marginalised and, by the height of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, considered thoroughly disreputable. In the first century B.C.,

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

declared, "dramatic art and the theatre is generally disgraceful". During this time, permanent theater-building was forbidden and other popular entertainments often took theater's place. Actors, who were mainly foreigners, freedmen and slaves, had become a disenfranchised class. They were forbidden to leave the profession and were required to pass their employment on to their children.

Mime

A mime artist, or simply mime (from Greek language, Greek , , "imitator, actor"), is a person who uses ''mime'' (also called ''pantomime'' outside of Britain), the acting out of a story through body motions without the use of speech, as a the ...

s included female performers, were heavily sexual in nature and often equated with

prostitution

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, no ...

. Attendance at such performances, says Barish, must have seemed to many Romans like visiting the brothels, "equally urgent, equally provocative of guilt, and hence equally in need of being scourged by a savage backlash of official disapproval".

Christian attitudes

Early Christian leaders, concerned to promote high ethical principles amongst the growing Christian community, were naturally opposed to the degenerate nature of contemporary Roman theatre. However, other arguments were also advanced.

In the second century,

Tatian

Tatian of Adiabene, or Tatian the Syrian or Tatian the Assyrian, (; ; ; ; – ) was an Assyrian Christian writer and theologian of the 2nd century.

Tatian's most influential work is the Diatessaron, a Biblical paraphrase, or "harmony", of the ...

and later

Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

, put forward

ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

principles. In ''

De spectaculis'', Tertullian argued that even moderate pleasure is to be avoided and that theater, with its large crowds and deliberately exciting performances, led to "mindless absorption in the imaginary fortunes of nonexistent characters". Absorbing Plato’s concept of mimesis into a Christian context, he also argued that acting was an ever-increasing system of falsifications. "First the actor falsifies his identity, and so compounds a deadly sin. If he impersonates someone vicious, he further compounds the sin." And if physical modification was required, say a man representing a woman, it was a "lie against our own faces, and an impious attempt to improve the works of the Creator".

In the fourth century, the famous preacher

Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; ; – 14 September 407) was an important Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and po ...

again stressed the ascetic theme. It was not pleasure but the opposite of pleasure that brought salvation. He wrote that "he who converses of theatres and actors does not benefit

is soul but inflames it more, and renders it more careless... He who converses about hell incurs no dangers, and renders it more sober."

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

, his North African contemporary, had in early life led a hedonistic lifestyle which changed dramatically following his conversion. In his ''

Confessions,'' echoing Plato, he says about imitating others: "To the end that we may be true to our nature, we should not become false by copying and likening to the nature of another, as do the actors and the reflections in the mirror ... We should instead seek that truth which is not self-contradictory and two-faced."

Augustine also challenged the cult of personality, maintaining that hero worship was a form of idolatry in which adulation of actors replaced the worship of God, leading people to miss their true happiness.

Theatre and church in the Middle Ages

Around AD 470, as Rome declined, the Roman Church increased in power and influence, and theater was virtually eliminated. In the Middle Ages, theatrical performance re-emerged as part of church life, telling Bible stories in a dramatic way; the aims of the church and of theater had now converged and there was very little opposition.

One of the few surviving examples of anti-theatrical attitude is found in ''A Treatise of Miraclis Pleyinge,'' a fourteenth-century sermon by an anonymous preacher. The sermon is generally agreed to be of

Lollard

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

inspiration. It is not clear if the text refers to the performance of

mystery plays on the streets or to

liturgical drama

Liturgical drama refers to medieval forms of dramatic performance that use stories from the Bible or Christian hagiography. The term has developed historically and is no longer used by most researchers. It was widely disseminated by well-known the ...

in the church. Possibly the author makes no distinction. Barish traces the basis of the preacher's prejudice to the lifelike immediacy of the theater, which sets it in unwelcome competition to everyday life and to the doctrines held in schools and churches. The preacher declares that since a play's basic objective is to please, its purpose must be suspect because

Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

never laughed. If one laughs or cries at a play it is because of the "pathos of the story". One's expression of emotion is therefore useless in the eyes of God. The playmaking itself is at fault. "It is the concerted, organized, professionalized nature of the enterprise that offends so deeply, the fact that it entails planning and teamwork and elaborate preparation, making it different from the kind of sin that is committed inadvertently, or in a fit of ungovernable passion."

16th and 17th century English theatre

Theatricality in the church

In 1559,

Thomas Becon, an English priest, wrote ''The Displaying of the Popish Mass'', an early expression of emerging Protestant theology, while in

exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

during the reign of

Queen Mary. His argument was with the Church and the ritualised theatricality of the mass. "By introducing ceremonial costume, ritual gesture, and symbolic decor, and by separating the clergy from the laity, the church has perverted a simple communal event into a portentous masquerade, a magic show designed to hoodwink the ignorant." He believed that in a mass with too much pomp, the laity became passive spectators, entertained in a production that became a substitute for the message of God.

English Renaissance theatre

The first English theatres were not built until the last quarter of the 16th century. One in eight Londoners regularly watched performances of Marlowe, Shakespeare, Jonson and others, an attendance rate only matched since by cinema around 1925–1939. Objections were made, to

live performances rather than to dramatic work itself or to its writers, and some objectors made an explicit exception for

closet drama

A closet drama is a play (theatre), play that is not intended to be performed onstage, but read by a solitary reader. The earliest use of the term recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is in 1813. The literary historian Henry Augustin Beers, H ...

s, especially those that were religious or had religious content.

Variations of Plato's reasoning on mimesis re-emerged. One problem was the representation of rulers and the high-born by those of low birth. Another issue was that of

effeminization in the

boy player

A boy player was a male child or teenager who performed in Medieval theatre, Medieval and English Renaissance theatre, English Renaissance playing companies. Some boy players worked for adult companies and performed the female roles, since women ...

when he took on female clothing and gesture. Both

Ben Jonson

Benjamin Jonson ( 11 June 1572 – ) was an English playwright, poet and actor. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence on English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the satire, satirical ...

and

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

used cross-dressing as significant themes within their plays, and Laura Levine (1994) explores this issue in ''Men in Women's Clothing: Anti-theatricality and Effeminization, 1579-1642.'' In 1597

Stephen Gosson said that theatre "effeminized" the mind, and four years later

Philip Stubbes claimed that male actors who wore women's clothing could "adulterate" male gender. Further tracts followed, and 50 years later

William Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669), an English lawyer, voluble author, polemicist and political figure, was a prominent Puritan opponent of church policy under William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1633–1645). His views were Presbyter ...

who described a man whom cross-dressing had caused to "degenerate" into a woman. Levine suggests these opinions reflect a deep anxiety over collapse into the feminine.

Gosson and Stubbs were both playwrights. Ben Jonson was against the use of theatrical costume because it lent itself to unpleasing mannerisms and an artificial triviality.

[ In his plays, he rejected the Elizabethan theatricality that often relied on special effects, regarding it as involving false conventions.][ His own court masques were expensive, exclusive spectacles. He put typical anti-theatrical arguments into the mouth of his ]Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

preacher Zeal-of-the-Land-Busy, in ''Bartholomew Fair

The Bartholomew Fair was one of London's pre-eminent summer charter fairs. A charter for the fair was granted by King Henry I to fund the Priory of St Bartholomew in 1133. It took place each year on 24 August (St Bartholomew's Day) within the p ...

,'' including the view that men mimicking women was forbidden in the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, in that the Book of Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

22 verse 5, the text states that "The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman's garment: for all that do so are an abomination unto the Lord thy God." JV

Puritan opposition

William Prynne's encyclopedic '' Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy,'' represents the culmination of the Puritan attack on English Renaissance theatre and on celebrations such as

William Prynne's encyclopedic '' Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy,'' represents the culmination of the Puritan attack on English Renaissance theatre and on celebrations such as Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a Religion, religious and Culture, cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by coun ...

, the latter alleged to have been derived from pagan Roman festivals. Although a particularly acute and comprehensive attack which emphasised spiritual and moral objections, it represented a common anti-theatrical view held by many during this time.

Prynne's outstanding objection to theater was that it encouraged pleasure and recreation over work, and that its excitement and effeminacy increased sexual desire.

1642–1660 – Theatre closure

By 1642, the Puritan view prevailed. As the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. An estimated 15% to 20% of adult males in England and Wales served in the military at some point b ...

got underway, London theaters were closed down. The order cited the current "times of humiliation" and their incompatibility with "public stage-plays", representative of "lascivious Mirth and Levity". After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the performance of plays was again allowed. Under a new licensing system, two London theatres with royal patents were opened.

Restoration theatre

Initially, the theatres performed many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms, but soon, new genres of Restoration comedy and Restoration spectacular evolved. A Royal Warrant from Charles II, who loved the theatre, brought English women onto the stage for the first time, putting an end to the practice of the 'boy player' and creating an opportunity for actresses to take on 'breeches' roles. This, says historian Antonia Fraser, meant that Nell Gwynn, Peg Hughes and others could show off their pretty legs in shows more titillating than ever before.

Historian George Clark (1956) said the best-known fact about Restoration drama was that it was immoral. The dramatists mocked at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper. "The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it." Antonia Fraser (1984) took a more relaxed approach, describing the Restoration as a liberal or permissive era.

The satirist, Tom Brown (1719) wrote, 'tis as hard a matter for a pretty Woman to keep herself honest in a Theatre as 'tis for an Apothecary to keep his treacle from the Flies in Hot Weather, for every Libertine in the Audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot...'

The Restoration ushered in the first appearance of the casting couch in English social history. Most actresses were poorly paid and needed to supplement their income in other ways. Of the eighty women who appeared on the Restoration stage, twelve enjoyed an ongoing reputation as courtesans, being maintained by rich admirers of rank (including the King); at least another twelve left the stage to become 'kept women' or prostitutes. It was generally assumed that thirty of the women who had brief stage careers came from the brothels and had later returned to them. About a quarter of the actresses were considered to live respectable lives, most being married to fellow actors.

Fraser reports that 'by the 1670s a respectable woman could not give her profession as "Actoress" and expect to keep either her reputation or her person intact... The word actress had secured in England that raffish connotation which would linger round it, for better or for worse, in fiction as well as in fact, for the next 250 years.'

Initially, the theatres performed many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms, but soon, new genres of Restoration comedy and Restoration spectacular evolved. A Royal Warrant from Charles II, who loved the theatre, brought English women onto the stage for the first time, putting an end to the practice of the 'boy player' and creating an opportunity for actresses to take on 'breeches' roles. This, says historian Antonia Fraser, meant that Nell Gwynn, Peg Hughes and others could show off their pretty legs in shows more titillating than ever before.

Historian George Clark (1956) said the best-known fact about Restoration drama was that it was immoral. The dramatists mocked at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper. "The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it." Antonia Fraser (1984) took a more relaxed approach, describing the Restoration as a liberal or permissive era.

The satirist, Tom Brown (1719) wrote, 'tis as hard a matter for a pretty Woman to keep herself honest in a Theatre as 'tis for an Apothecary to keep his treacle from the Flies in Hot Weather, for every Libertine in the Audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot...'

The Restoration ushered in the first appearance of the casting couch in English social history. Most actresses were poorly paid and needed to supplement their income in other ways. Of the eighty women who appeared on the Restoration stage, twelve enjoyed an ongoing reputation as courtesans, being maintained by rich admirers of rank (including the King); at least another twelve left the stage to become 'kept women' or prostitutes. It was generally assumed that thirty of the women who had brief stage careers came from the brothels and had later returned to them. About a quarter of the actresses were considered to live respectable lives, most being married to fellow actors.

Fraser reports that 'by the 1670s a respectable woman could not give her profession as "Actoress" and expect to keep either her reputation or her person intact... The word actress had secured in England that raffish connotation which would linger round it, for better or for worse, in fiction as well as in fact, for the next 250 years.'

17th century Europe

Jansenism was the moral adversary to the theater in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and in that respect similar to Puritanism in England. However, Barish argues, "the debate in France proceeds on an altogether more analytical, more intellectually responsible plane. The antagonists attend more carefully to the business of argument and the rules of logic; they indulge less in digression and anecdote."[

]

Jansenism

Jansenists, rather like the Calvinists, denied the freedom of human will stating that "man can do nothing—could not so much as obey the ten commandments—without an express interposition of grace, and when grace came, its force was irresistible". Pleasure was forbidden because it became addictive.[ According to ]Pierre Nicole

Pierre Nicole (; 19 October 1625 – 16 November 1695) was a French writer and one of the most distinguished of the French Jansenists.

Life

Born in Chartres in 1625, Nicole was the son of a provincial barrister, who took in charge his education ...

, a distinguished Jansenist, the moral objection was, not so much about the makers of theater, or about the vice-den of the theater-space itself, or about the disorder it is presumed to cause, but rather about the intrinsically corrupting content. When an actor expresses base actions such as lust, hate, greed, vengeance, and despair, he must draw upon something immoral and unworthy in his own soul. Even positive emotions must be recognised as mere lies performed by hypocrites. The concern was a psychological one for, by experiencing these things, the actor stirs up heightened, temporal emotions, both in himself and in the audience, emotions that need to be denied. Therefore, both the actor and audience should feel ashamed for their collective participation.[

]

Francois de La Rochefoucauld (1731)

In ''Reflections on the Moral Maxims','' Francois de La Rochefoucauld wrote about the innate manners we were all born with and "when we copy others, we forsake what is authentic to us and sacrifice our own strong points for alien ones that may not suit us at all". By imitating others, including the good, all things are reduced to ideas and caricatures of themselves. Even with the intent of betterment, imitation leads directly to confusion. Mimesis ought therefore to be abandoned entirely.[

]

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, the Genevan philosopher, held the primary belief that all men were created good and that it was society that attempted to corrupt. Luxurious things were primarily to blame for these moral corruptions and, as stated in his ''Discourse on the Arts'', ''Discourse on the Origins of Inequality'' and ''Letter to d'Alembert'', the theater was central to this downfall. Rousseau argued for a nobler, simpler life free of the "perpetual charade of illusion, created by self-interest and self-love".The use of women in theater was disturbing for Rousseau; he believed women were designed by nature especially for modest roles and not for those of an actress. "The new society is not in fact to be encouraged to evolve its own morality but to revert to an earlier one, to the paradisal time when men were hardy and virtuous, women housebound and obedient, young girls chaste and innocent. In such a reversion, the theater—with all it symbolizes of the hatefulness of society, its hypocrisies, its rancid politeness, its heartless masqueradings—has no place at all."

18th century

By the end of the 17th century, the moral pendulum had swung back. Contributory factors included the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

of 1688, William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

and Mary's dislike of the theatre, and the lawsuits brought against playwrights by the Society for the Reformation of Manners (founded in 1692). When Jeremy Collier attacked playwrights like Congreve and Vanbrugh in his '' Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage'' in 1698, accusing them of profanity, blasphemy, indecency, and undermining public morality through the sympathetic depiction of vice, he was confirming a shift in audience taste that had already taken place.

Censorship

Censorship of stage plays had been exercised by the Master of the Revels

The Master of the Revels was the holder of a position within the English, and later the British, royal household, heading the "Revels Office" or "Office of the Revels". The Master of the Revels was an executive officer under the Lord Chamberla ...

in England from Elizabethan times until the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

closing theatres in 1642, closure remaining until the Restoration in 1660. In 1737, a pivotal moment in theatrical history, Parliament enacted the Licensing Act, a law to censor plays on the basis of both politics and morals (sexual impropriety, blasphemy, and foul language). It also limited spoken drama to the two patent theatres. Plays had to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain. Parts of these law were enforced unevenly. The act was modified by the Theatres Act 1843, which led later to the building of many new theatres across the country. Censorship was only finally abolished by the Theatres Act in 1968. (As the new medium of film developed in the 20th Century, the 1909 Cinematograph Act was passed. Initially a health and safety measure, its implementation soon included censorship. In time the British Board of Film Classification

The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is a non-governmental organization, non-governmental organisation founded by the British film industry in 1912 and responsible for the national classification and censorship of films exhibited ...

became the ''de facto'' film censor for films in the United Kingdom.)

Early America

In 1778, just two years after declaring the United States as a nation, a law was passed to abolish theater, gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of Value (economics), value ("the stakes") on a Event (probability theory), random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy (ga ...

, horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance activity, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its bas ...

, and cockfighting

Cockfighting is a blood sport involving domesticated roosters as the combatants. The first documented use of the word gamecock, denoting use of the cock as to a "game", a sport, pastime or entertainment, was recorded in 1634, after the term ...

, all on the grounds of their sinful nature. This forced theatrical practice into the American universities where it is also met with hostility, particularly from Timothy Dwight IV

Timothy Dwight (May 14, 1752January 11, 1817) was an American academic and educator, a Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He was the eighth president of Yale College (1795–1817).

Early life

Timothy Dwight was born May 14, 17 ...

of Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

and John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense real ...

of Princeton College.[ The latter, in his work, ''Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage'', outlined arguments similar to those of his predecessors, but added a further moral argument that as theater was truthful to life, it was therefore an improper method of instruction. "Now are not the great majority of characters in real life bad? Must not the greatest part of those represented on the stage be bad? And therefore, must not the strong impression which they make upon the spectators be hurtful in the same proportion?"][

In her 1832 book '']Domestic Manners of the Americans

''Domestic Manners of the Americans'' is a two-volume travel book by Frances Milton Trollope, published in 1832, which follows her travels through America and her residence in Cincinnati, at the time still a frontier town.

Context

Frances Troll ...

'', English writer Fanny Trollope noted how poorly attended theaters were in the American cities she visited, observing that women in particular "are rarely seen there, and by far the larger proportion of females deem it an offence against religion to witness the representation of a play."[Trollope, Fanny, ''Domestic Manners of the Americans'', Ch. 8.]

/ref>

After delivering the eulogy at the 1865 funeral of Abraham Lincoln, Phineas Gurley commented:

It will always be a matter of deep regret to thousands that our lamented President fell in the theater; that the dastardly assassin found him, shot him there. Multitudes of his best friends - I mean his Christian friends - would have preferred that he should have fallen in almost any other place. Had he been murdered in his bed, or in his office, or on the street, or on the steps of the Capitol, the tidings of his death would not have struck the Christian heart of the country quite so painfully; for the feeling of that heart is that the theater is one of the last places to which a good man should go and among the very last in which his friends would wish him to die.[Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. V, March 1948, No.i, p.24.]

/ref>

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, a renowned English politician, had been a theatre-goer in his youth but, following an evangelical conversion while a Member of Parliament, gradually changed his attitudes, his behaviour and his lifestyle. Most notably, he became a prime leader of the movement to stop the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

. The conspicuous involvement of Evangelicals and Methodists in the highly popular anti-slavery movement served to improve the status of a group otherwise associated with the less popular campaigns against vice and immorality. Wilberforce expressed his views on authentic faith in ''A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Middle and Higher Classes in this Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity'' (1797).William Hague

William Jefferson Hague, Baron Hague of Richmond (born 26 March 1961) is a British politician and life peer who was Leader of the Conservative Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1997 to 2001 and Deputy Leader from 2005 to 2010. He was th ...

, says of Wilberforce,

19th and early 20th century (psychomachia)

As theatre grew, so also did theatre-based anti-theatricality. Barish comments that from our present vantage point, nineteenth-century attacks on theater frequently have the air of a psychomachia, that is, a dramatic expression of the battle of good versus evil

In philosophy, religion, and psychology, "good and evil" is a common dichotomy. In religions with Manichaean and Abrahamic influence, evil is perceived as the dualistic antagonistic opposite of good, in which good should prevail and evil sho ...

.[

]

Art versus theatre

Various notables including

Various notables including Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, Konstantin Stanislavsky, the actress Eleonora Duse, Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi ( ; ; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi, his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma ...

, and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, regarded the uncontrollable narcissism of Edmund Kean and those like him with despair. They were appalled by the self-regarding mania that the theatre induced in those whose lot it was to parade, night after night, before crowds of clamorous admirers. Playwrights found themselves driven towards closet drama, just to avoid the corruption of their work by self-aggrandizing actors.

For Romantic writers such as Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

, totally devoted to Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, stage performances inevitably sullied the beauty and integrity of the original work which the mind alone could appreciate. The fault of the theater lay in its superficiality. The delicacy of the written word was crushed by histrionic actors and distracting scenic effects.Auguste Comte

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the ...

, although a keen theater-goer, like Plato, banned all theater from his idealist society. Theater was a "concession to our weakness, a symptom of our irrationality, a kind of placebo of the spirit with which the good society will be able to dispense".Modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

would lead to a completely fresh and trenchant anti-theatricalism, beginning with attacks on Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

who could be considered the 'inventor' of avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

theatricalism. Wagner became the object of Modernism's most polemic anti-theatrical attackers. Martin Puchner states that Wagner, 'almost like a stage diva himself, continues to stand for everything that may be grandiose and compelling, but also dangerous and objectionable, about the theatre and theatricality.' Critics have included Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

, Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin ( ; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German-Jewish philosopher, cultural critic, media theorist, and essayist. An eclectic thinker who combined elements of German idealism, Jewish mysticism, Western M ...

and Michael Fried. Puchner argues that 'No longer interested in banishing actors or closing down theaters, modernist anti-theatricalism does not remain external to the theater but instead becomes a productive force responsible for the theater's most glorious achievements'.

Church versus theatre

'Psychomachia' applies even more to the battle of Church versus Stage. The Scottish Presbyterian Church's exertions concerning Kean were more overtly focussed on the spiritual battle. The English newspaper, '' The Era'', sometimes known as the ''Actor's Bible,'' reported:In 1860, the report of a sermon, a now occasional but still ferocious attack on the morality of the theatre, was submitted to ''The Era'' by an actor, S. Price:

According to Price, who had attended the service, the minister declared that the present class of professionals, with very few exceptions, were dissipated in private and rakish in public, and that they pandered to the depraved and vitiated tastes of playgoers. Furthermore, theatre managers "held out the strongest inducements to women of an abandoned character to visit their theatres, in order to encourage the attendance of those of the opposite sex.

American author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church Ellen G. White wrote her concern that theatricality, among other forms of entertainment, would hinder one's spirituality and morality. She wrote in one of her books, ''Testimonies for the Church vol. 4'':

In France the opposition was even more intense and ubiquitous. The ''Encyclopedie théologique'' (1847) records: "The excommunication pronounced against comedians, actors, actresses tragic or comic, is of the greatest and most respectable antiquity... it forms part of the general discipline of the French Church... This Church allows them neither the sacraments nor burial; it refuses them its suffrages and its prayers, not only as infamous persons and public sinners, but as excommunicated persons... One must deal with the comedians as with public sinners, remove them from participation with holy things while they belong to the theater, admit when they leave it."

Literature and theatricality

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

drew attention to vantage point when he recalled that a grand-aunt had asked him to get her some books by Restoration playwright Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; baptism, bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration (England), Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writ ...

that she remembered from her youth. She later returned the books, recommending they be burnt and saying, "Is it not a very odd thing that I, an old woman of eighty and upwards, sitting alone, feel myself ashamed to read a book which, sixty years ago, I have heard read aloud for the amusement of large circles, consisting of the first and most creditable society in London."

In Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

's ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by the English author Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton (publisher), Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray (publishing house), John Murray, st ...

'' (1814), Sir Thomas Bertram gives expression to social anti-theatrical views. Returning from his slave plantations in Antigua, he discovers his adult children preparing an amateur production of Elizabeth Inchbald's '' Lovers Vows.'' He argues vehemently, using statements such as "unsafe amusements" and "noisy pleasures" that will "offend his ideas of decorum

Decorum (from the Latin: "right, proper") was a principle of classical rhetoric, poetry, and theatrical theory concerning the fitness or otherwise of a style to a theatrical subject. The concept of ''decorum'' is also applied to prescribed lim ...

" and burns all unbound copies of the play. Fanny Price, the heroine, judges that the two leading female roles in ''Lovers Vows'' are "unfit to be expressed by any woman of modesty". ''Mansfield Park'', with its strong moralist theme and criticism of corrupted standards, has generated more debate than any other of Austen's works, polarising supporters and critics. It sets up an opposition between a vulnerable young woman with strongly held religious and moral principles against a group of worldly, highly cultivated, well-to-do young people who pursue pleasure without principle.[Byrne, Paula. ''The Real Jane Austen: A Life in Small Things,'' (2013) chapter 8 (Kindle Location 2471). HarperCollins Publishers.]

Barish suggests that by 1814 Austen may have turned against theatre following a supposed recent embracing of evangelicalism.

Barish suggests that by 1814 Austen may have turned against theatre following a supposed recent embracing of evangelicalism.Claire Tomalin

Claire Tomalin (née Delavenay; born 20 June 1933) is an English journalist and biographer known for her biographies of Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, Samuel Pepys, Jane Austen and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Early life

Tomalin was born Claire Delaven ...

(1997) argues that there is no need to believe Austen condemned plays outside ''Mansfield Park'' and every reason for thinking otherwise.

Building bridges

Earlier divergence of church and stage

An editorial in ''The Era'', quoted a contemporary writer outlining the history of the divergence of Church and Stage following the Middle Ages, and arguing that the conflict was unnecessary:

In the second half of the 19th century, Evangelical Christians established many societies for the relief of poverty. Some were created to help working women, particularly those whose occupation placed them in 'exceptional moral danger'. Evangelical groups tended towards 'charity' for the oppressed. 'Christian Socialists', distinctively different, (as in the ''Church and Stage Guild'') were more likely to direct their energies towards what they considered to be the root causes of poverty.

1873 – The Theatrical Mission

The Theatrical Mission was formed by two Evangelicals in 1873 to support vulnerable girls employed in travelling companies, the first being a group in a company that went on tour after performing their pantomime at the Crystal Palace. By 1884, the Mission was sending out some 1,000 supportive letters a month. They then opened a club, ' Macready House', in Henrietta Street, close to the London theatres, that provided cheap lunches and teas, and later, accommodation. They looked after children employed on the stage and, for any girl who was pregnant, encouraged her to seek help from the Theatre Ladies Guild which would arrange for the confinement and find other work for her after the baby was born. The Mission attracted royal patronage. Towards the end of the century, an undercover journalist from ''The Era'' investigated Macready House, reporting it as 'patronising to the profession' and sub-standard.

1879 – Church and Stage Guild

In November 1879, ''The Era'', responding to a resurgence of interest in religious circles about the Stage, reported a lecture defending the stage at a Nottingham church gathering. The speaker noted increased tolerance amongst church people and approved of the recent formation of the ''Church and Stage Guild''. For too long, the clergy had referred to theatre as the 'Devil's House'. The chairman in his summary stated that while there was good in the theatre, he did not think the clergy could support the Stage as presently constituted.

The ''Church and Stage Guild'' had been founded earlier that year by the Rev Stewart Headlam

Stewart Duckworth Headlam (12 January 1847 – 18 November 1924) was an English Anglican priest who was involved in frequent controversy in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Headlam was a pioneer and publicist of Christian socialism, ...

on 30 May. Within a year it had more than 470 members with at least 91 clergy and 172 professional theatre people. Its mission included breaking down "the prejudice against theatres, actors, music hall artists, stage singers, and dancers." Headlam had been removed from his previous post by John Jackson, Bishop of London, following a lecture Headlam gave in 1877 entitled ''Theatres and Music Halls'' in which he promoted Christian involvement in these establishments. Jackson, writing to Headlam, and after distancing himself from any Puritanism, said, "I do pray earnestly that you may not have to meet before the Judgment Seat those whom your encouragement first led to places where they lost the blush of shame and took the first downward step towards vice and misery."

1895 "The Sign of the Cross"

''The Kansas City Journal'' reported on Wilson Barrett's new play, a religious drama, '' The Sign of the Cross,'' a work intended to bring church and stage closer together''.''

Ben Greet

Sir Philip Barling Greet (24 September 1857 – 17 May 1936), known professionally as Ben Greet, was a British William Shakespeare, Shakespearean actor, director, impresario and actor-manager.

Early life

The younger son of Captain William Gre ...

, an English actor-manager with a number of companies, formed a touring ''Sign of the Cross'' Company. The play proved particularly popular in England and Australia and was performed for several decades, often drawing audiences that did not normally attend the theatre.

1865–1935 – A theatre manager's perspective

William Morton was a provincial theatre manager in England whose management experience spanned the 70 years between 1865 and 1935. He often commented on his experiences of theatre and cinema, and also reflected on national trends. He challenged the church when he believed it to be judgmental or hypocritical. He also strove to bring quality entertainment to the masses, though the masses did not always respond to his provision. Over his career, he reported a very gradual acceptance of theatre by the 'respectable classes' and by the church. Morton was a committed Christian though not a party man in religion or politics. A man of principle, he maintained an unusual policy of no-alcohol in all his theatres.

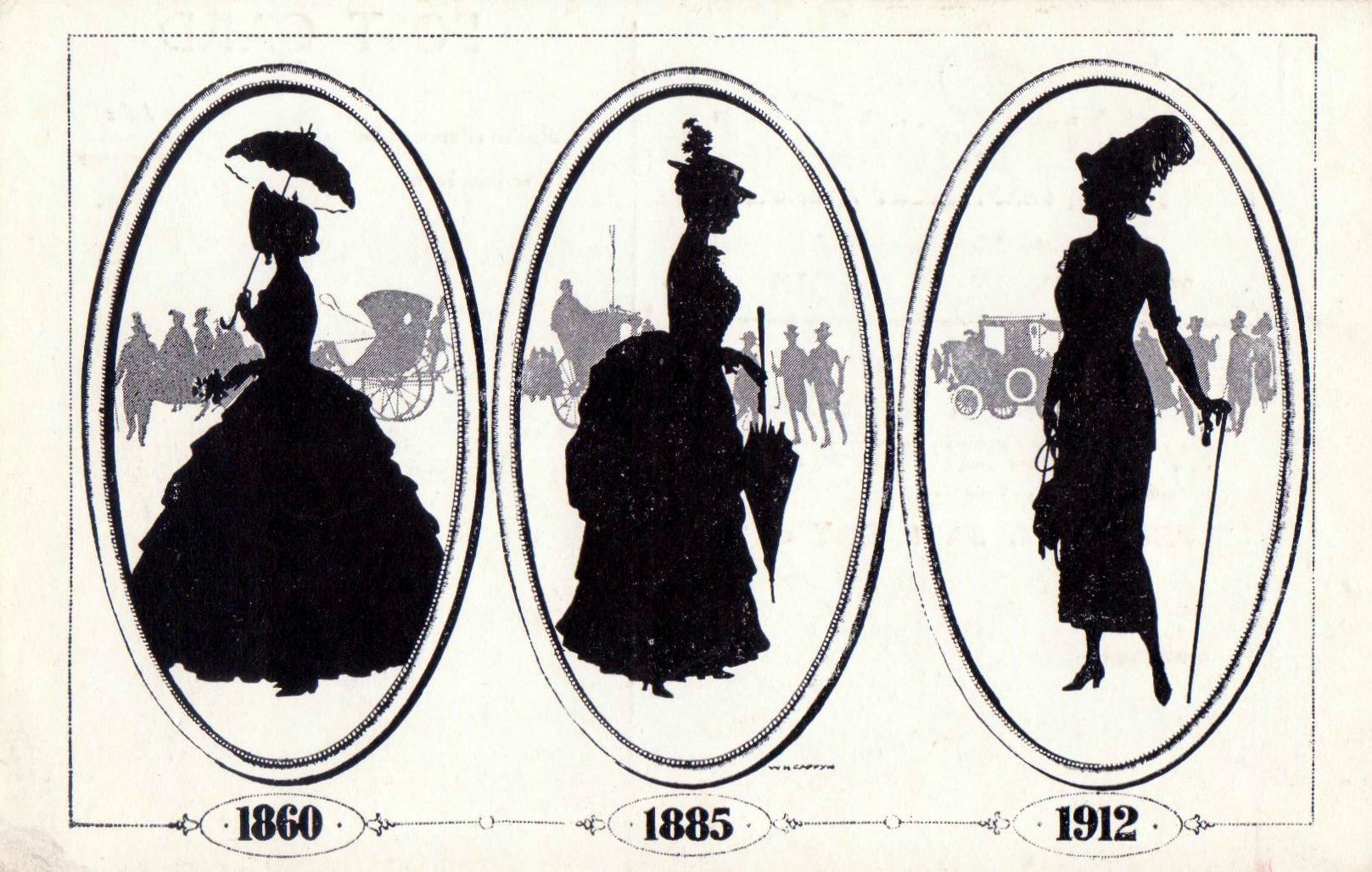

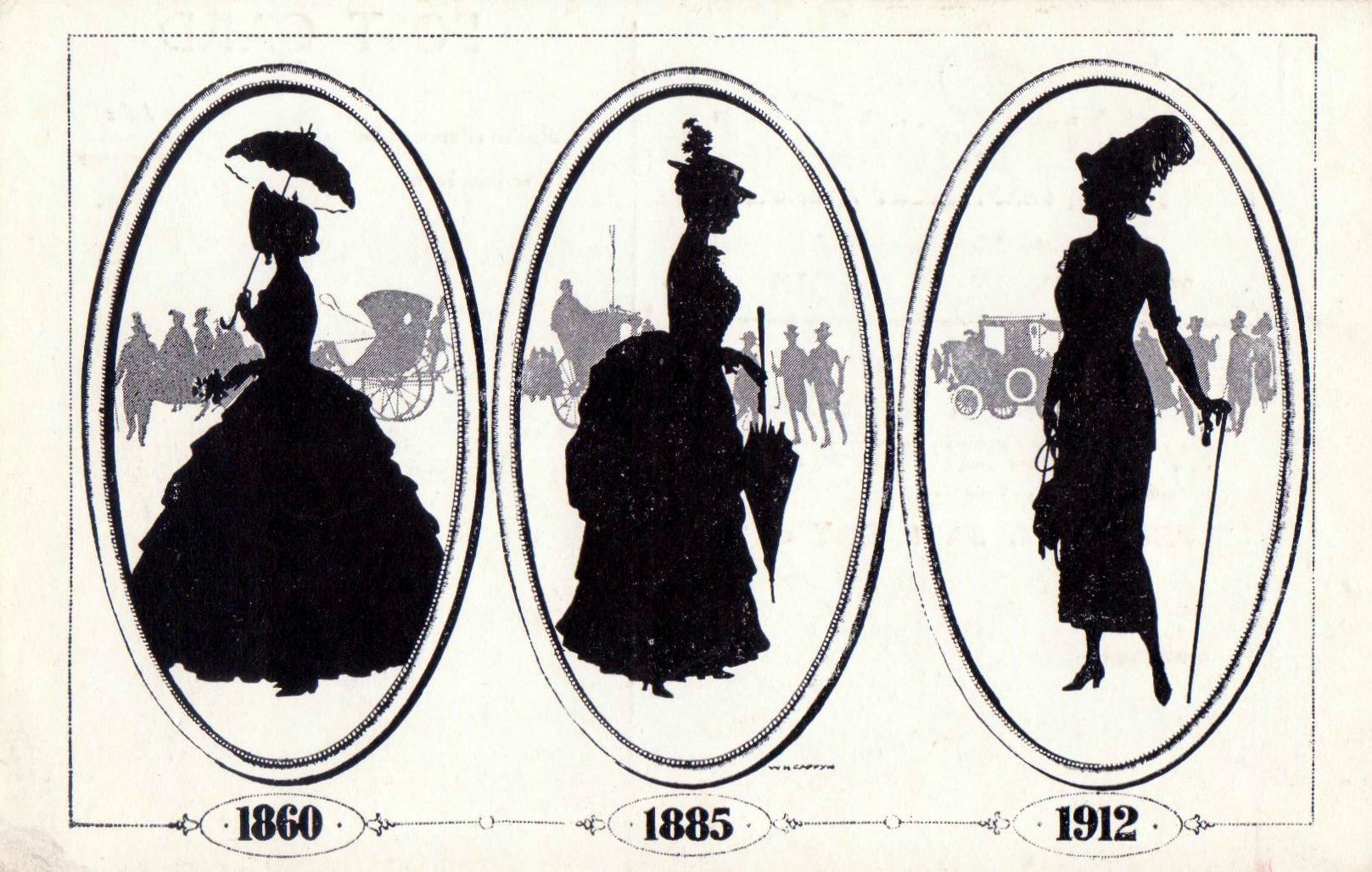

1860s bigotry

Morton commented in his memoirs, "At this period there was more bigotry than now. As a rule the religious community looked upon actors and press men as less godly than other people." "Prejudice against the theatre was widespread amongst the respectable classes whose tastes were catered for by non-theatrical shows." The ''Hull Daily Mail'' echoed, "To many of extreme religious views, his profession was anathema". It also reported that many had considered Morton's profession "a wasteful extravagance which lured young people from the narrow path they should tread".['One Hundred And Fifty', ''Hull Daily Mail,'' 24 January 1938 p. 4]

1910 – The same goal

Morton stated in a public lecture held at Salem Chapel that he censured clergy "when they go out their way to preach against play-acting and warn their flock not to see it". In another lecture he said that "the Protestant Church took too prejudiced a view against the stage. Considering their greater temptations I do not consider that actors are any worse than the rest of the community. Both the Church and the Stage are moving to the same goal. No drama is successful which makes vice triumphant. Many of the poor do not go to church and chapel, and but for the theatre they might come to fail to see the advantage in being moral".

1921 – Actor's Church Union

Morton received a circular from a Hull vicar, Rev. R. Chalmers. It described his small parish as full of evil-doing aliens, the crime-plotting homeless and a floating population of the theatrical profession. Said ''The Stage'', this "represents a survival of that antagonistic spirit to the stage which the work of the Actors' Church Union has done so much to kill".['Hull has a Hell—', ''The Stage,'' 17 March 1921 p.14] (Chalmers was noted for his charitable work so the real issue may have been more about poor communication.)

1938 – Greater tolerance

Morton lived to see greater tolerance. On his hundredth birthday the ''Hull Daily'' ''Mail'' said Morton was held in great respect, "even by those who would not dream of entering any theatre. Whatever he brought for his patrons, grand opera, musical comedy, drama, or pantomime, came as a clean, wholesome entertainment."

See also

* Excommunication of actors by the Catholic Church

Many bishops, priests, and monks have strongly condemned theatrical amusements, and they even declared the actors to be "instruments of Satan", "a curse to the Church", and "beguiling unstable souls". The Roman Catholic Church believed theatre caus ...

References

Further reading

*

*

*

*

* {{cite journal, author=Williams, K., date=Fall 2001, title=Anti-theatricality and the Limits of Naturalism, journal=Modern Drama, volume=44, number=3, pages=284–99, doi=10.3138/md.44.3.284

Theatre criticism

Theatre of the United Kingdom

British drama

History of theatre

Antitheatricality is any form of opposition or hostility to

Antitheatricality is any form of opposition or hostility to  Around AD 470, as Rome declined, the Roman Church increased in power and influence, and theater was virtually eliminated. In the Middle Ages, theatrical performance re-emerged as part of church life, telling Bible stories in a dramatic way; the aims of the church and of theater had now converged and there was very little opposition.

One of the few surviving examples of anti-theatrical attitude is found in ''A Treatise of Miraclis Pleyinge,'' a fourteenth-century sermon by an anonymous preacher. The sermon is generally agreed to be of

Around AD 470, as Rome declined, the Roman Church increased in power and influence, and theater was virtually eliminated. In the Middle Ages, theatrical performance re-emerged as part of church life, telling Bible stories in a dramatic way; the aims of the church and of theater had now converged and there was very little opposition.

One of the few surviving examples of anti-theatrical attitude is found in ''A Treatise of Miraclis Pleyinge,'' a fourteenth-century sermon by an anonymous preacher. The sermon is generally agreed to be of

William Prynne's encyclopedic '' Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy,'' represents the culmination of the Puritan attack on English Renaissance theatre and on celebrations such as

William Prynne's encyclopedic '' Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy,'' represents the culmination of the Puritan attack on English Renaissance theatre and on celebrations such as  Initially, the theatres performed many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms, but soon, new genres of Restoration comedy and Restoration spectacular evolved. A Royal Warrant from Charles II, who loved the theatre, brought English women onto the stage for the first time, putting an end to the practice of the 'boy player' and creating an opportunity for actresses to take on 'breeches' roles. This, says historian Antonia Fraser, meant that Nell Gwynn, Peg Hughes and others could show off their pretty legs in shows more titillating than ever before.

Historian George Clark (1956) said the best-known fact about Restoration drama was that it was immoral. The dramatists mocked at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper. "The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it." Antonia Fraser (1984) took a more relaxed approach, describing the Restoration as a liberal or permissive era.

The satirist, Tom Brown (1719) wrote, 'tis as hard a matter for a pretty Woman to keep herself honest in a Theatre as 'tis for an Apothecary to keep his treacle from the Flies in Hot Weather, for every Libertine in the Audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot...'

The Restoration ushered in the first appearance of the casting couch in English social history. Most actresses were poorly paid and needed to supplement their income in other ways. Of the eighty women who appeared on the Restoration stage, twelve enjoyed an ongoing reputation as courtesans, being maintained by rich admirers of rank (including the King); at least another twelve left the stage to become 'kept women' or prostitutes. It was generally assumed that thirty of the women who had brief stage careers came from the brothels and had later returned to them. About a quarter of the actresses were considered to live respectable lives, most being married to fellow actors.

Fraser reports that 'by the 1670s a respectable woman could not give her profession as "Actoress" and expect to keep either her reputation or her person intact... The word actress had secured in England that raffish connotation which would linger round it, for better or for worse, in fiction as well as in fact, for the next 250 years.'

Initially, the theatres performed many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms, but soon, new genres of Restoration comedy and Restoration spectacular evolved. A Royal Warrant from Charles II, who loved the theatre, brought English women onto the stage for the first time, putting an end to the practice of the 'boy player' and creating an opportunity for actresses to take on 'breeches' roles. This, says historian Antonia Fraser, meant that Nell Gwynn, Peg Hughes and others could show off their pretty legs in shows more titillating than ever before.

Historian George Clark (1956) said the best-known fact about Restoration drama was that it was immoral. The dramatists mocked at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper. "The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it." Antonia Fraser (1984) took a more relaxed approach, describing the Restoration as a liberal or permissive era.

The satirist, Tom Brown (1719) wrote, 'tis as hard a matter for a pretty Woman to keep herself honest in a Theatre as 'tis for an Apothecary to keep his treacle from the Flies in Hot Weather, for every Libertine in the Audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot...'

The Restoration ushered in the first appearance of the casting couch in English social history. Most actresses were poorly paid and needed to supplement their income in other ways. Of the eighty women who appeared on the Restoration stage, twelve enjoyed an ongoing reputation as courtesans, being maintained by rich admirers of rank (including the King); at least another twelve left the stage to become 'kept women' or prostitutes. It was generally assumed that thirty of the women who had brief stage careers came from the brothels and had later returned to them. About a quarter of the actresses were considered to live respectable lives, most being married to fellow actors.

Fraser reports that 'by the 1670s a respectable woman could not give her profession as "Actoress" and expect to keep either her reputation or her person intact... The word actress had secured in England that raffish connotation which would linger round it, for better or for worse, in fiction as well as in fact, for the next 250 years.'

Various notables including

Various notables including  Barish suggests that by 1814 Austen may have turned against theatre following a supposed recent embracing of evangelicalism.

Barish suggests that by 1814 Austen may have turned against theatre following a supposed recent embracing of evangelicalism.