Anti-Protestantism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Protestantism is

The

The  Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants, especially public ones, could be denounced as heretics and subject to prosecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by church and state as the

Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants, especially public ones, could be denounced as heretics and subject to prosecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by church and state as the

In 1870 the newly formed

In 1870 the newly formed

In Northern Ireland or pre- Catholic emancipation Ireland, there is a hostility to Protestantism as a whole that has more to do with communal or

In Northern Ireland or pre- Catholic emancipation Ireland, there is a hostility to Protestantism as a whole that has more to do with communal or

Poll of Catholics

* * {{Theology Relations between Christian denominations

bias

Bias is a disproportionate weight ''in favor of'' or ''against'' an idea or thing, usually in a way that is inaccurate, closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individ ...

, hatred

Hatred or hate is an intense negative emotional response towards certain people, things or ideas, usually related to opposition or revulsion toward something. Hatred is often associated with intense feelings of anger, contempt, and disgust. Hat ...

or distrust against some or all branches of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and/or its followers, especially when amplified in legal, political, ethic or military measures.

Protestants were not tolerated throughout most of Europe until the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 approved Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

as an alternative for Roman Catholicism as a state religion of various states within the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

was not recognized until the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire ...

of 1648. Other states, such as France, made similar agreements in the early stages of the Reformation. Poland–Lithuania had a long history of religious tolerance. However, the tolerance stopped after the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

in Germany, the persecution of Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

and the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

in France, the change in power between Protestant and Roman Catholic rulers after the death of Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

in England, and the launch of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

in Italy, Spain, Habsburg Austria and Poland-Lithuania. Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

arose as a part of the Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation represented a response to perceived corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Starting in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th cen ...

, lacking the support of the state which Lutheranism and Calvinism enjoyed, and thus was persecuted.

Protestants in Latin America were largely ostracized until the abolition of certain restrictions in the 20th century. Protestantism spread with Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

and Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a movement within the broader Evangelical wing of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes direct personal experience of God in Christianity, God through Baptism with the Holy Spirit#Cl ...

gaining the majority of followers. North America became a shelter for Protestants who were fleeing Europe after the persecution increased.

History

Reformation

The

The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

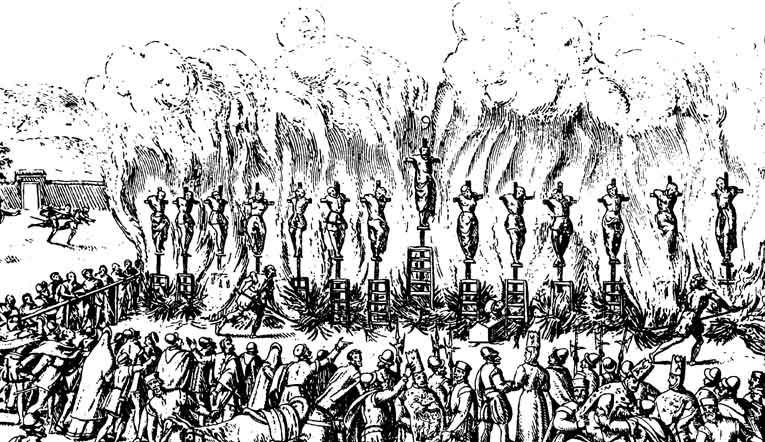

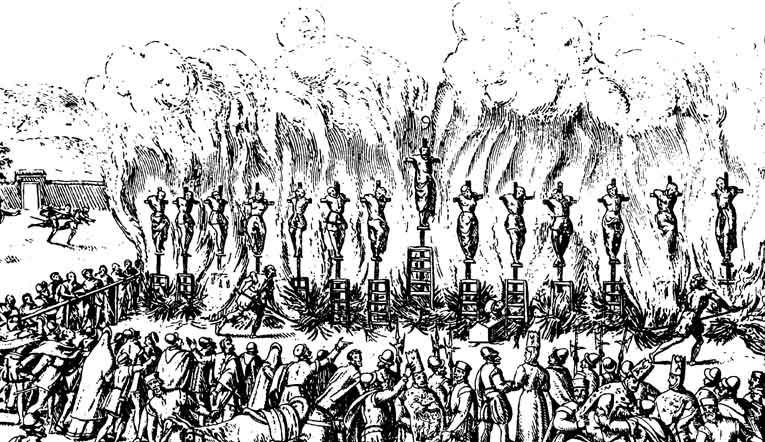

led to a long period of warfare and communal violence between Catholic and Protestant factions, sometimes leading to massacres and forced suppression of the alternative views by the dominant faction in much of Europe.

Various European rulers supported or opposed Roman Catholicism for their own political reasons. After the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

and its Counter Reformation program, religion became an excuse or factor for territorial wars (the religious wars

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a War, war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the exte ...

) and for periodic outbreaks of sectarian violence.

Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants, especially public ones, could be denounced as heretics and subject to prosecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by church and state as the

Anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by the Catholic Church against the Reformation of the 16th century. Protestants, especially public ones, could be denounced as heretics and subject to prosecution in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands in which the Catholics were the dominant power. This movement was orchestrated by church and state as the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

.

There were religious wars and, in some countries though not in others, eruptions of sectarian hatred such as the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572, part of the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

.

Militant anti-Protestantism originated in a reaction by states and societies alarmed at the spread of Protestantism following the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

of the 16th century, frequently dated from Martin Luther's 95 Theses of 1517. By 1540, Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III (; ; born Alessandro Farnese; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

He came to the papal throne in an era follo ...

had sanctioned the Society of Jesus (Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

) as the first religious society pledged to extinguish Protestantism.

Habsburg Europe

Protestantism was denounced as heresy, and those supporting these doctrines could be excommunicated as heretics. Thus by canon law and depending on the practice and policies of the particular Catholic country at the time, Protestants could be subject to prosecution and persecution: in those territories, such as Spain, Italy and the Netherlands, the Catholic rulers were then the dominant power. Some anti-Lutheran measures, such as the regionalSpanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

s had begun earlier in response to the Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

and Morisco

''Moriscos'' (, ; ; "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Catholic Church and Habsburg Spain commanded to forcibly convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed Islam. Spain had a sizeable Mus ...

and Converso

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert" (), was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of their descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian popula ...

conversions.

After the defeat of the rebellious Protestant Estates of the Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia (), sometimes referenced in English literature as the Czech Kingdom, was a History of the Czech lands in the High Middle Ages, medieval and History of the Czech lands, early modern monarchy in Central Europe. It was the pr ...

by the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

at the Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain (; ) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years.

It was fought on 8 November 16 ...

in 1620, the Habsburgs introduced a Counter-Reformation and forcibly converted all Bohemians, even the Utraquist Hussites, back to the Catholic Church. In 1624, Emperor Ferdinand II issued a patent that allowed only the Catholic religion in Bohemia. In the 1620s, Protestant nobility, burghers, and clergy of Bohemia and Austria were expelled from the Habsburg lands or forced to convert to Catholicism, and their lands were confiscated, while peasants were forced to adopt the religion of their new Catholic masters.

In a series of persecutions ending in 1731, over 20,000 Salzburg Protestants

The Salzburg Protestants () were Protestantism, Protestant refugees who had lived in the Catholic Archbishopric of Salzburg until the 18th century. In a series of persecutions ending in 1731, over 20,000 Protestants were expelled from their homel ...

were expelled from their homeland by the Prince-Archbishops.

France

In France, from 1562 Catholics andHuguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

(Reformed Protestants) fought a series of wars until the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

brought religious peace in 1598. It affirmed Catholicism as the state religion but granted considerable toleration to Protestants. The religious toleration lasted until the reign of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, who resumed persecution of Protestants and finally abolished their right to worship with the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to prac ...

in 1685.

Fascist Italy

In 1870 the newly formed

In 1870 the newly formed Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

annexed the remaining Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, depriving the Pope of his temporal power. However, Papal rule over Italy was later restored

''Restored'' is the fourth studio album by American contemporary Christian musician Jeremy Camp. It was released on November 16, 2004, by BEC Recordings.

Track listing

Standard release

Enhanced edition

Deluxe gold edition

Standard Aus ...

by the Italian Fascist régime (albeit on a greatly diminished scale) in 1929 as head of the Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

state; under Mussolini's dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

, Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

became the state religion of Fascist Italy.

In 1938, the Italian Racial Laws and '' Manifesto of Race'' were promulgated by the Fascist régime to both outlaw and persecute Italian Jews and Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

,;

especially Evangelicals and Pentecostals. Thousands of Italian Jews and a small number of Protestants died in the Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

.

Francoist Spain

In Franco'sauthoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

Spanish State (1936–1975), Protestantism was deliberately marginalized and persecuted. During the Civil War, Franco's regime persecuted the country's 30,000 Protestants, and forced many Protestant pastors to leave the country and various Protestant leaders were executed. Once authoritarian rule was established, non-Catholic Bibles were confiscated by police and Protestant schools were closed. Although the 1945 Spanish Bill of Rights granted freedom of ''private'' worship, Protestants suffered legal discrimination and non-Catholic religious services were not permitted publicly, to the extent that they could not be in buildings which had exterior signs indicating it was a house of worship and that public activities were prohibited.

Ireland

In Northern Ireland or pre- Catholic emancipation Ireland, there is a hostility to Protestantism as a whole that has more to do with communal or

In Northern Ireland or pre- Catholic emancipation Ireland, there is a hostility to Protestantism as a whole that has more to do with communal or nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

sentiments than theological issues. During the Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

by the Protestant state of England in the course of the 16th century, the Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female per ...

state failed to convert Irish Catholics to Protestantism and thus followed a vigorous policy of confiscation, deportation, and resettlement. By dispossessing Catholics of their lands, and resettling Protestants on them, the official Government policy was to encourage a widespread campaign of proselytizing by Protestant settlers and establishment of English law in these areas. This led to a counter effort of the Counter Reformation by mostly Jesuit Catholic clergy to maintain the "old religion" of the people as the dominant religion in these regions. The result was that Catholicism came to be identified with a sense of nativism and Protestantism came to be identified with the State, as most Protestant communities were established by state policy, and Catholicism was viewed as treason to the state after this time. While Elizabeth I had initially tolerated private Catholic worship, this ended after Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

, in his 1570 papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

'' Regnans in Excelsis'', pronounced her to be illegitimate and unworthy of her subjects' allegiance.

The Penal Laws, first introduced in the early 17th century, were initially designed to force the native elite to conform to the state church by excluding non-Conformists and Roman Catholics from public office, and restricting land ownership, but were later, starting under Queen Elizabeth, also used to confiscate virtually all Catholic owned land and grant it to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland. The Penal Laws had a lasting effect on the population, due to their severity (celebrating Catholicism in any form was punishable by death or enslavement under the laws), and the favouritism granted Irish Anglicans served to polarise the community in terms of religion. Anti-Protestantism in Early Modern Ireland 1536–1691 thus was also largely a form of hostility to the colonisation of Ireland. Irish poetry of this era shows a marked antipathy to Protestantism, one such poem reading, "The faith of Christ atholicismwith the faith of Luther is like ashes in the snow". The mixture of resistance to colonization and religious disagreements led to widespread massacres of Protestant settlers in the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 was an uprising in Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, initiated on 23 October 1641 by Catholic gentry and military officers. Their demands included an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and ...

. Subsequent religious or sectarian

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or religious conflicts between groups. Others conceive of sectarianism a ...

antipathy was fueled by the atrocities committed by both sides in the Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Confederate Wars, took place from 1641 to 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, all then ...

, especially the repression of Catholicism during and after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the Commonwealth of England, initially led by Oliver Cromwell. It forms part of the 1641 to 1652 Irish Confederate Wars, and wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three ...

, when Irish Catholic land was confiscated en masse, clergy were executed and discriminatory legislation was passed against Catholics.

The Penal Laws against Catholics (and also Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

) were renewed in the late 17th and early 18th centuries due to fear of Catholic support for Jacobitism

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

after the Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland took place from March 1689 to October 1691. Fought between Jacobitism, Jacobite supporters of James II of England, James II and those of his successor, William III of England, William III, it resulted in a Williamit ...

and were slowly repealed in 1771–1829. Penal Laws against Presbyterians were relaxed by the Toleration Act 1719, due to their siding with the Jacobites in a 1715 rebellion. At the time the Penal Laws were in effect, Presbyterians and other non-Conformist Protestants left Ireland and settled in other countries. Some 250,000 left for the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

alone between the years 1717 and 1774, most of them arriving there from Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

.

Sectarian conflict was continued in the late 18th century in the form of communal violence between rival Catholic and Protestant factions over land and trading rights (see Defenders (Ireland)

The Defenders were a Catholic agrarian secret society in 18th-century Ireland, founded in County Armagh. Initially, they were formed as local defensive organisations opposed to the Protestant Peep o' Day Boys; however, by 1790 they had become ...

, Peep O'Day Boys

The Peep o' Day Boys was an agrarian sectarian Protestant association in 18th-century Ireland. Originally noted as being an agrarian society around 1779–80, from 1785 it became the Protestant component of the sectarian conflict that emerge ...

and Orange Institution

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

). The 1820s and 1830s in Ireland saw a major attempt by Protestant evangelists to convert Catholics, a campaign which caused great resentment among Catholics.

In modern Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

, anti-Protestantism is usually more nationalist than religious in tone. The main reason for this is the identification of Protestants with unionism – i.e. the support for the maintenance of the union with the United Kingdom, and opposition to Home Rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

or Irish independence. In Northern Ireland, since the foundation of the Free State in 1921, Catholics, who were mainly nationalists, suffered systematic discrimination from the Protestant unionist majority. The Cameron Report – Disturbances in Northern Ireland (1969) The same happened to Protestants in the Catholic-dominated South. ot in citation givenref name="Lord Cameron"/>

The mixture of religious and national identities on both sides reinforces both anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant sectarian

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or religious conflicts between groups. Others conceive of sectarianism a ...

prejudice in the province.

More specifically religious anti-Protestantism in Ireland was evidenced by the acceptance of the Ne Temere decrees in the early 20th century, whereby the Catholic Church decreed that all children born into mixed Catholic-Protestant marriages had to be brought up as Catholics. Protestants in Northern Ireland had long held that their religious liberty would be threatened under a 32-county Republic of Ireland, due to that country's Constitutional support of a "special place" for the Roman Catholic Church. This article was deleted in 1972.

The Troubles

DuringThe Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

in Northern Ireland, Protestants with no connection to the security forces were occasionally targeted by Irish republican paramilitaries

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both ...

.

In 1974, two Protestant employees at a filling station on the Crumlin Road in Belfast were shot and killed by members of the IRA. In an alleged statement read out at the trial of one of the IRA members charged, the killings were said to have been planned in retaliation for the killings of two Catholics at another filling station.

In 1976, eleven Protestant workmen were shot by a group which was identified in a telephone call as the "South Armagh Republican Action Force". Ten of the men died, and the sole survivor said, "One man... did all the talking and proceeded to ask each of us our religion. Our Roman Catholic works colleague was ordered to clear off and the shooting started." A 2011 report from the Historical Enquiries Team

The Historical Enquiries Team was a unit of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) set up in September 2005 to investigate the 3,269 unsolved murders committed during the Troubles, specifically between 1968 and 1998. It was wound up in S ...

(HET) found, "These dreadful murders were carried out by the Provisional IRA

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

and none other."

In 1983, members of the Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA, ) is an Irish republicanism, Irish republican Socialism, socialist paramilitary group formed on 8 December 1974, during the 30-year period of conflict known as "the Troubles". The group seeks to remove ...

(INLA) shot 10 worshippers who were attending a Protestant church service near the village of Darkley in County Armagh

County Armagh ( ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It is located in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and adjoins the southern shore of Lough Neagh. It borders t ...

. Three of those shot were killed. The gunmen issued a statement, claiming to be from the "Catholic Reaction Force", and said that they "could easily have taken the lives of at least 20 more innocent Protestants". They demanded that loyalist paramilitarites "call an immediate halt to their vicious indiscriminate campaign against innocent Catholics", or the gunmen would "make the Darkley killings look like a picnic."McKittrick, David, ''Lost lives: the stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles'' (Edinburgh, Scotland: Mainstream, 1999), p. 963

See also

*Religious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

* Anti-Christian sentiment

** Anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

** Anti-Eastern Orthodox sentiment

** Anti-Oriental Orthodox sentiment

** Anti-Mormonism

* Black legend (Spain)

* Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

* List of people burned as heretics

A list is a Set (mathematics), set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of t ...

*Criticism of Protestantism

Criticism of Protestantism covers critiques and questions raised about Protestantism, the Christian denominations which arose out of the Protestant Reformation. While critics may praise some aspects of Protestantism which are not unique to the ...

*Hindu terrorism

Hindu terrorism, or sometimes Hindutva terror, or metonymically saffron terror, refer to terrorist acts carried out, on the basis of motivations in broad association with Hindu nationalism or Hindutva.

The phenomenon became a topic of conte ...

** Violence against Christians in India

References

External links

Poll of Catholics

* * {{Theology Relations between Christian denominations