Annie Beasant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English

Money was short and Frank Besant was stingy. Annie Besant was sure a third child would impose too much on the family finances. She wrote short stories, books for children, and articles, the money she earned being controlled by her husband.

Besant began to question her own faith, after her daughter Mabel was seriously ill in 1871. She consulted Edward Bouverie Pusey: by post he gave her advice along orthodox, Bampton Lecture lines, and in person he sharply reprimanded her unorthodox theological tendencies. She attended in London, with her mother, a service at St George's Hall given by the heterodox cleric Charles Voysey, in autumn 1871, and struck up an acquaintance with the Voyseys, reading in "theistic" authors such as Theodore Parker and Francis Newman on Voysey's recommendation. Voysey also introduced Besant to the freethinker and publisher Thomas Scott. Encouraged by Scott, Besant wrote an anonymous pamphlet ''On the Deity of Jesus of Nazareth'', by "the wife of a beneficed clergyman", which appeared in 1872. Ellen Dana Conway, wife of Moncure Conway befriended Annie at this time.

The Besants made an effort to repair the marriage. The tension came to a head when Annie Besant refused to attend Communion, which Frank Besant demanded, now fearing for his own reputation and position in the Church. In 1873 she left him and went to London. She had a temporary place to stay, with Moncure Conway. The Scotts found her a small house in Colby Road,

Money was short and Frank Besant was stingy. Annie Besant was sure a third child would impose too much on the family finances. She wrote short stories, books for children, and articles, the money she earned being controlled by her husband.

Besant began to question her own faith, after her daughter Mabel was seriously ill in 1871. She consulted Edward Bouverie Pusey: by post he gave her advice along orthodox, Bampton Lecture lines, and in person he sharply reprimanded her unorthodox theological tendencies. She attended in London, with her mother, a service at St George's Hall given by the heterodox cleric Charles Voysey, in autumn 1871, and struck up an acquaintance with the Voyseys, reading in "theistic" authors such as Theodore Parker and Francis Newman on Voysey's recommendation. Voysey also introduced Besant to the freethinker and publisher Thomas Scott. Encouraged by Scott, Besant wrote an anonymous pamphlet ''On the Deity of Jesus of Nazareth'', by "the wife of a beneficed clergyman", which appeared in 1872. Ellen Dana Conway, wife of Moncure Conway befriended Annie at this time.

The Besants made an effort to repair the marriage. The tension came to a head when Annie Besant refused to attend Communion, which Frank Besant demanded, now fearing for his own reputation and position in the Church. In 1873 she left him and went to London. She had a temporary place to stay, with Moncure Conway. The Scotts found her a small house in Colby Road,

Besant met fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater in London in April 1894. They became close co-workers in the theosophical movement and would remain so for the rest of their lives. Leadbeater claimed

Besant met fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater in London in April 1894. They became close co-workers in the theosophical movement and would remain so for the rest of their lives. Leadbeater claimed

In 1916, Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices. This was the first political party in India to have regime change as its main goal. Unlike the Congress itself, the League worked all year round. It built a structure of local branches, enabling it to mobilise demonstrations, public meetings, and agitations. In June 1917, Besant was arrested and interned at a

In 1916, Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices. This was the first political party in India to have regime change as its main goal. Unlike the Congress itself, the League worked all year round. It built a structure of local branches, enabling it to mobilise demonstrations, public meetings, and agitations. In June 1917, Besant was arrested and interned at a

List of Works on Online Book

Annie Besant (Besant, Annie, 1847-1933) , The Online Books Page

br /> List of Work on Open Librar

Annie Wood Besant

* ''The Political Status of Women'' (1874)''The Political Status of Women'' (1874) was Besant's first public lecture. Carol Hanbery MacKay, ''Creative Negativity: Four Victorian Exemplars of the Female Quest'' (Stanford University, 2001), 116–117. * ''Christianity: Its Evidences, Its Origin, Its Morality, Its History'' (1876) *

The Law of Population

' (1877) *

My Path to Atheism

' (1878, 3rd ed 1885) *

Marriage, As It Was, As It Is, And As It Should Be: A Plea for Reform

' (1878) * ''Light, Heat and Sound'' (1881) *

The Atheistic Platform: 12 Lectures

' Nos. 1, 5, 9 and 12 by Besant (1884) *

Autobiographical Sketches

' (1885) *

Why I Am a Socialist

' (1886) *

Why I Became a Theosophist

' (1889) *

The Seven Principles of Man

' (1892) *

Bhagavad Gita

' (translated as ''The Lord's Song'') (1895) * ''Karma'' (1895) *

In the Outer Court

'(1895) * ''The Ancient Wisdom'' (1897) * ''Dharma'' (1898) * ''Evolution of Life and Form'' (1898) * ''Avatâras'' (1900) *

The Religious Problem in India

' (1901) *

Thought Power: Its Control and Culture

' (1901) * ''A Study in Consciousness: A contribution to the science of psychology.'' (1904) * ''Theosophy and the new psychology: A course of six lectures'' (1904) * '' Thought Forms'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1905) *

Esoteric Christianity

' (1905 2nd ed) * ''Death - and After?'' (1906) * ''Occult Chemistry'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1908

Occult chemistry;: clairvoyant observations on the chemical elements

* '' An Introduction to Yoga'' (1908

An introduction to yoga; four lectures delivered at the 32nd anniversary of the Theosophical Society, held at Benares, on Dec. 27th, 28th, 29th, 30th, 1907

*

Australian Lectures

' (1908) *

Annie Besant: An Autobiography

' (1908 2nd ed) * ''The Religious Problem in India'' Lectures on Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, Theosophy (1909

The religious problem in India: four lectures delivered during the twenty-sixth annual convention of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, Madras, 1901

* ''Man and His Bodies'' (1896, rpt 1911

* '' Elementary Lessons on Karma'' (1912) * '' A Study in Karma'' (1912) * ''Initiation: The Perfecting of Man'' (1912

Theosophy: Initiation The Perfecting of Man by Annie Besant - MahatmaCWLeadbeater.org

* ''Giordano Bruno'' (1913) * ''Man's Life in This and Other Worlds'' (1913

Man's life in this and other worlds

* ''Man: Whence, How and Whither'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1913

Man, whence, how and whither: a record of clairvoyant investigation / by Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater.

* ''Theosophy and Life's Deeper Problems'' 1916 * ''The Doctrine of the Heart'' (1920

*

The Future of Indian Politics

' 1922 * ''The Life and Teaching of Muhammad'' (1932

Annie Besant The Life And Teachings Of Muhammad ( The Prophet Of Islam)

* ''Memory and Its Nature'' (1935

* Various writings regarding

Blavatsky Archives contains 100s of articles on HP Blavatsky & Theosophy

* Selection of Pamphlets as follows

Pamphlets

:* "Sin and Crime" (1885) :* "God's Views on Marriage" (1890) :* "A World Without God" (1885) :* "Life, Death, and Immortality" (1886) :* "Theosophy" (1925?) :* "The World and Its God" (1886) :* "Atheism and Its Bearing on Morals" (1887) :* "On Eternal Torture" (n.d.) :* "The Fruits of Christianity" (n.d.) :* "The Jesus of the Gospels and the Influence of Christianity" (n.d.) :* "The Gospel of Christianity and the Gospel of Freethought" (1883) :* "Sins of the Church: Threatenings and Slaughters" (n.d.) :* "For the Crown and Against the Nation" (1886) :* "Christian Progress" (1890) :* "Why I Do Not Believe in God" (1887) :* "The Myth of the Resurrection" (1886) :* "The Teachings of Christianity" (1887) Indian National Movement :* The Commonweal (a weekly dealing on Indian national issues) :*New India (a daily newspaper which was a powerful mouthpiece for 15 years advocating Home Rule and revolutionizing Indian journalism)

Annie Besant

Biography a

varanasi.org.in

* ttp://www.alpheus.org/html/articles/theosophy/bevir3.html Annie Besant's Quest for Truth: Christianity, Secularism, and New Age Thought*Framke, Maria

Besant, Annie

in

* * ttps://www.freemasonryformenandwomen.co.uk/ The British Federation of the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, Le Droit Humain, founded by Annie Besant in 1902br>The International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, Le Droit HumainAnnie Besant perused 2000 words in the Odia languageThought power, its control, and culture

Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. *

"Character Sketch: October of Mrs. Annie Besant" 349–367 in ''Review of Reviews'' IV:22, October 1891.

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Besant, Annie 1847 births 1933 deaths 19th-century English women writers 19th-century Indian philanthropists 19th-century Indian politicians 19th-century Indian women politicians 19th-century Indian women writers 19th-century Indian writers 20th-century Indian philanthropists 20th-century Indian politicians 20th-century Indian women politicians 20th-century Indian women writers 20th-century Indian writers Alumni of Birkbeck, University of London Banaras Hindu University people British birth control activists English women's rights activists English reformers English activists English emigrants to India English Freemasons English non-fiction writers English occult writers English people of Irish descent British socialist feminists English spiritual writers British suffragists English Theosophists English women activists Esoteric Christianity Feminism and spirituality British feminist writers Former Anglicans Former atheists and agnostics Founders of Indian schools and colleges History of Chennai Indian suffragists Indian women philanthropists Members of the Fabian Society Members of the London School Board New Age predecessors New religious movement mystics People from Clapham People from Sibsey Presidents of the Indian National Congress Scouting and Guiding in India Social Democratic Federation members Translators of the Bhagavad Gita Victorian women writers Victorian writers Women Indian independence activists Women mystics Malthusians

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, theosophist, freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

and Home Rule activist, educationist

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education also fol ...

and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an ardent supporter of both Irish and Indian self-rule. She became the first female president of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in 1917.

She became a prominent speaker for the National Secular Society

The National Secular Society (NSS) is a British campaigning organisation that promotes secularism and the separation of church and state. It holds that no one should gain advantage or disadvantage because of their religion or lack of it. The Soc ...

(NSS), as well as a writer, and a close friend of Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Br ...

. In 1877 they were prosecuted for publishing a book by birth control campaigner Charles Knowlton. Thereafter, she became involved with union actions, including the Bloody Sunday demonstration and the London matchgirls strike of 1888. She was a leading speaker for both the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

and the Marxist Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on 7 June 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury, James ...

(SDF). She was also elected to the London School Board for Tower Hamlets, topping the poll, even though few women were qualified to vote at that time.

In 1890 Besant met Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian-born Mysticism, mystic and writer who emigrated to the United States where she co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an internat ...

, and over the next few years her interest in theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

grew, whilst her interest in secular matters waned. She became a member of the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

and a prominent lecturer on the subject. As part of her theosophy-related work, she travelled to India. In 1898 she helped establish the Central Hindu School, and in 1922 she helped establish the Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board

The Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board or HSNC Board () is an Indian non-profit organisation founded in 1922 (or 1919) in the British India province of Sind Province (1936–1955), Sind and moved to Bombay, India after the 1947 Partition ...

in Bombay (today's Mumbai

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial capital and the most populous city proper of India with an estimated population of 12 ...

), India. The Theosophical Society Auditorium in Hyderabad, Sindh

Hyderabad, also known as Neroonkot, is the capital and largest city of the Hyderabad Division in the Sindh province of Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Sindh by population, second-largest city in Sindh, after Karachi, and the List of citie ...

(Sindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

) is called Besant Hall in her honor. In 1902, she established the first overseas Lodge of the International Order of Co-Freemasonry, Le Droit Humain

The International Order of Freemasonry ''Le Droit Humain'' is a global Masonic order, membership of which is available to men and women on equal terms, regardless of nationality, religion or ethnicity. This practice is known as Co-Freemasonry ...

. Over the next few years, she established lodges in many parts of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. In 1907 she became president of the Theosophical Society, whose international headquarters were, by then, located in Adyar, Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

(Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

).

Besant also became involved in politics in India, joining the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

. When World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in 1914, she helped launch the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

to campaign for democracy in India, and dominion status within the British Empire. This led to her election as president of the Indian National Congress, in late 1917. In the late 1920s, Besant travelled to the United States with her protégé and adopted son Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti ( ; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian Philosophy, philosopher, speaker, writer, and Spirituality, spiritual figure. Adopted by members of the Theosophy, Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill ...

, who she claimed was the new Messiah and incarnation of Buddha. Krishnamurti rejected these claims in 1929. After the war, she continued to campaign for Indian independence and for the causes of theosophy, until her death in 1933.

Early life

Annie Wood was born on 1 October 1847 inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, the daughter of William Burton Persse Wood (1816–1852) and his wife Emily Roche Morris (died 1874). Her father was English, attended Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

, and attained a medical degree; her mother was an Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

. Her paternal grandfather Robert Wright Wood was a brother of Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet.

Wood's father died when she was five years old, leaving a son, Henry Trueman Wood, and one daughter. Her mother supported Henry's education at Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (school founder), John Lyon, a local landowner an ...

, by running a boarding house there. Annie was fostered by Ellen Marryat, sister of the author Frederick Marryat, who ran a school at Charmouth

Charmouth is a village and civil parish in west Dorset, England. The village is situated on the mouth of the River Char, around north-east of Lyme Regis. Dorset County Council estimated that in 2013 the population of the civil parish was 1,31 ...

, until age 16. She returned to her mother at Harrow self-confident, aware of a sense of duty to society, and under the influence of the Tractarians. As a young woman, she was also able to travel in Europe.

In summer 1867, Wood and her mother stayed at Pendleton near Manchester with the radical solicitor William Prowting Roberts, who questioned Wood's political assumptions. In December of that year, at age 20, Annie married the cleric Frank Besant (1840–1917), younger brother of Walter Besant

Sir Walter Besant (; 14 August 1836 – 9 June 1901) was an English novelist and historian. William Henry Besant was his brother, and another brother, Frank, was the husband of Annie Besant.

Early life and education

The son of wine merchant Wi ...

, an evangelical, serious Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

.

Marriage and separation

The Rev. Frank Besant was a graduate ofEmmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I. The site on which the college sits was once a priory for Dominican mo ...

, ordained priest in 1866, but had no living: in 1866 he was teaching at Stockwell Grammar School as second master, and in 1867 he moved to teach at Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

as assistant master. In 1872, he became vicar of Sibsey in Lincolnshire, a benefice in the gift of the Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

—who was Lord Hatherley, a Wood family connection, son of Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet. The Besant family, with their two children, Arthur and Mabel, moved to Sibsey, but the marriage was already under strain. As Besant wrote in her ''Autobiography'', "we were an ill-matched pair".

Upper Norwood

Upper Norwood is an area of south London, England, within the London Boroughs of London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borough of Croydon, Croydon, London Borough of Lambeth, Lambeth and London Borough of Southwark, Southwark. It is north ...

.

The couple were legally separated and Annie Besant took her daughter Mabel with her, the agreement of 25 October 1873 giving her custody. Annie remained with Mrs. Besant for the rest of her life. At first, she was able to keep contact with both children and to have Mabel live with her; she also got a small allowance from her husband. In 1878 Frank Besant successfully argued her unfitness, after Annie Besant's public campaigning on contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, and had custody from then of both children. Later, Annie Besant was reconciled with her son and daughter. Her son Arthur Digby Besant (1869–1960) was President of the Institute of Actuaries, 1924–26, and wrote ''The Besant Pedigree'' (1930). Initially in London, Besant attempted to support her daughter, her mother (who died the following year) and herself with needlework

Needlework refers to decorative sewing and other textile arts, textile handicrafts that involve the use of a Sewing needle, needle. Needlework may also include related textile crafts like crochet (which uses a crochet hook, hook), or tatting, ( ...

.

Reformer and secularist

Besant began in 1874 to write for the '' National Reformer'', the organ of theNational Secular Society

The National Secular Society (NSS) is a British campaigning organisation that promotes secularism and the separation of church and state. It holds that no one should gain advantage or disadvantage because of their religion or lack of it. The Soc ...

(NSS), run by Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Br ...

. She also continued to write for Thomas Scott's small press. On the account given by W. T. Stead, Besant had encountered the ''National Reformer'' on sale in the shop of Edward Truelove. Besant had heard of Bradlaugh from Moncure Conway. She wrote to Bradlaugh and was accepted as an NSS member. She first heard him speak on 2 August 1874.

Through Bradlaugh, Besant met and became a supporter of Joseph Arch, the farmworkers' leader.

Her career as a platform speaker began on 25 August 1874, with topic "The Political Status of Women". The lecture was at the Co-operative Hall, Castle Street, Long Acre in Covent Garden. It was followed in September by an invitation from Moncure Conway to speak at his Camden Town church on "The True Basis of Morality". Besant published an essay under this title, in 1882. She was a prolific writer and a powerful orator.Mark Bevir, ''The Making of British Socialism'' (Princeton University, 2011), 202. She addressed causes including freedom of thought

Freedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by developing knowledge, concepts, theo ...

, women's rights, secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

, birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, Fabian socialism and workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, ...

. Margaret Cole called her "the finest woman orator and organiser of her day".

Criticism of Christianity

Besant opined that for centuries the leaders of Christian thought spoke of women as a necessary evil and that the greatest saints of the Church were those who despised women the most, "Against the teachings of eternal torture, of the vicarious atonement, of the infallibility of the Bible, I leveled all the strength of my brain and tongue, and I exposed the history of the Christian Church with unsparing hand, its persecutions, its religious wars, its cruelties, its oppressions." In the section named "Its Evidences Unreliable" of her work "Christianity", Besant presents the case of why theGospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

s are not authentic: "before about A.D. 180 there is no trace of FOUR gospels among the Christians."

''The Fruits of Philosophy''

Besant and Bradlaugh set up the Freethought Publishing Company at the beginning of 1877; it followed the 1876 prosecution of Charles Watts, and they carried on his work. They became household names later that year, when they published '' Fruits of Philosophy'', a book by the American birth-control campaigner Charles Knowlton. It claimed that working-class families could never be happy until they were able to decide how many children they wanted. It also suggested ways to limit the size of their families. The Knowlton book was highly controversial and was vigorously opposed by the Church. Besant and Bradlaugh proclaimed in the ''National Reformer'':We intend to publish nothing we do not think we can morally defend. All that we publish we shall defend.The pair were arrested and put on trial for publishing the Knowlton book. They were found guilty but released pending appeal. The trial became a ''

cause célèbre

A ( , ; pl. ''causes célèbres'', pronounced like the singular) is an issue or incident arousing widespread controversy, outside campaigning, and heated public debate. The term is sometimes used positively for celebrated legal cases for th ...

'', and ultimately the verdict was overturned on a technical legal point.

Besant was then instrumental in founding the Malthusian League, reviving a name coined earlier by Bradlaugh. It would go on to advocate for the abolition of penalties for the promotion of contraception. Besant and Bradlaugh supported the Malthusian League for some 12 years. They were concerned with birth control, but were not neo-Malthusians in the sense of convinced believers in the tradition of Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

and his demographic theories. Besant did advocate population control as an antidote to the struggle for survival. She became the secretary of the League, with Charles Robert Drysdale as President. In time the League veered towards eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

, and it was from the outset an individualist

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

organisation, also for many members supportive of a social conservatism

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on Tradition#In political and religious discourse, traditional social structures over Cultural pluralism, social pluralism. Social conservatives ...

that was not Besant's view. Her pamphlet ''The Law of Population'' (1878) sold well.

Radical causes

Besant was a leading member of the National Secular Society alongside Charles Bradlaugh. She attacked the status of theChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

as established church. The NSS argued for a secular state and an end to the special status of Christianity and allowed her to act as one of its public speakers. On 6 March 1881 she spoke at the opening of Leicester Secular Society Leicester Secular Society is the world's oldest Secularism, Secular Society. It meets at its headquarters, the Leicester Secular Hall in the centre of Leicester, England, at 75 Humberstone Gate.

Founding

Founded in 1851, the society is the oldest ...

's new Secular Hall in Humberstone Gate, Leicester. The other speakers were George Jacob Holyoake, Harriet Law and Bradlaugh.

Bradlaugh was elected to Parliament in 1881. Because of his atheism, he asked to be allowed to affirm, rather than swear the oath of loyalty. It took more than six years before the matter was completely resolved, in Bradlaugh's favour, after a series of by-elections and court appearances. He was an individualist and opposed to socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

in any form. While he defended free speech, he was very cautious about encouraging working-class militancy.

Edward Aveling, a rising star in the National Secular Society, tutored Besant during 1879, and she went on to a degree course at London University. Then, 1879 to 1882, she was a student of physical sciences at Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution. Embarrassed by her activist reputation, the Institution omitted her name from the published list of graduands, and mailed her certificates to her. When Aveling in a speech in 1884 announced he had become a socialist after five years close study, Besant argued that his politics over that whole period had been aligned with Bradlaugh's and her own. Aveling and Eleanor Marx

Jenny Julia Eleanor Marx (16 January 1855 – 31 March 1898), sometimes called Eleanor Aveling and known to her family as Tussy, was the English-born youngest daughter of Karl Marx. She was herself a Socialism, socialist activist who sometimes ...

joined the Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on 7 June 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury, James ...

, followers of Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, and then the Socialist League, a small Marxist splinter group which formed around the artist William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

. In 1883 Besant started her own periodical, ''Our Corner''. It was a literary and in time a socialist monthly, and published George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

's novel ''The Irrational Knot'' in serial form.

Meanwhile, Besant built close contacts with the Irish Home Rulers and supported them in her newspaper columns during what are considered crucial years, when the Irish nationalists were forming an alliance with Liberals and Radicals. Besant met the leaders of the Irish home rule movement. In particular, she got to know Michael Davitt, who wanted to mobilise the Irish peasantry through a Land War, a direct struggle against the landowners. She spoke and wrote in favour of Davitt and his Land League many times over the coming decades.

Personal life

Bradlaugh's family circumstances changed in May 1877 with the death of his wife Susannah, analcoholic

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Hea ...

who had left him for James Thomson. His two children, Alice then aged 21, and Hypatia

Hypatia (born 350–370 – March 415 AD) was a Neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt (Roman province), Egypt: at that time a major city of the Eastern Roman Empire. In Alexandria, Hypatia was ...

then 19, returned to live with him from his in-laws. He had been able to take a house in St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden and the City of Westminster, London, England, about 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Historically the northern part of the Civil Parish#An ...

in February of that year, at 20 Circus Road, near Besant. They continued what had become a close friendship.

Fabian Society 1885–1890

Besant made an abrupt public change in her political views, at the 1885 New Year's Day meeting of the London Dialectical Society, founded by Joseph Hiam Levy to promote individualist views. It followed a noted public debate at St. James's Hall on 17 April 1884, on ''Will Socialism Benefit the English People?'', in which Bradlaugh had put individualist views, against the Marxist line of Henry Hyndman. On that occasion Besant still supported Bradlaugh. While Bradlaugh may have had the better of the debate, followers then began to migrate into left-wing politics. George Bernard Shaw was the speaker on 1 January 1885, talking on socialism, but, instead of the expected criticism from Besant, he saw her opposing his opponent. Shaw then sponsored Besant to join theFabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

.

The Fabians were defining political goals, rejecting anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

in 1886, and forming the Fabian Parliamentary League, with both Besant and Shaw on its Council which promoted political candidacy. Unemployment was a central issue of the time, and in 1887 some of the London unemployed started to hold protests in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was established in the early-19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. Its name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy, ...

. Besant agreed to appear as a speaker at a meeting on 13 November. The police tried to stop the assembly, fighting broke out, and troops were called. Many were hurt, one man died, and hundreds were arrested; Besant offered herself for arrest, an offer disregarded by the police. The events became known as Bloody Sunday. Besant threw herself into organising legal aid for the jailed workers and support for their families. In its aftermath the Law and Liberty League, defending freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, was formed by Besant and others, and Besant became editor of ''The Link'', its journal.

Besant's involvement in the London matchgirls strike of 1888 came after a Fabian Society talk that year on female labour by Clementina Black. Besant wrote in ''The Link'' about conditions at the Bryant & May match factory. She was drawn further into this battle of the "New Unionism" by a young socialist, Herbert Burrows, who had made contact with workers at the factory, in Bow. They were mainly young women, were very poorly paid, and subject to occupational disease, such as Phossy jaw caused by the chemicals used in match manufacture. Louise Raw in ''Striking a Light'' (2011) has, however, contested the historiography of the strike, stating that "A proper examination of the primary evidence about the strike makes it impossible to continue to believe that Annie Besant led it."

William Morris played some part in converting Besant to Marxism, but it was to the Social Democratic Federation of Hyndman, not his Socialist League, that she turned in 1888. She remained a member for a number of years and became one of its leading speakers. She was still a member of the Fabian Society, the two movements being compatible at the time. Besant was elected to the London School Board in 1888. Women at that time were not able to take part in parliamentary politics but had been brought into the London local electorate in 1881. Besant drove about with a red ribbon in her hair, speaking at meetings. "No more hungry children", her manifesto proclaimed. She combined her socialist principles with feminism:

"I ask the electors to vote for me, and the non-electors to work for me because women are wanted on the Board and there are too few women candidates."From the early 1880s Besant had also been an important feminist leader in London, with

Alice Vickery

Alice Vickery (also known as A. Vickery Drysdale and A. Drysdale Vickery, ''c.'' 1844 – 12 January 1929) was an English physician, campaigner for women's rights, and the first British woman to qualify as a chemist and pharmacist. She and her ...

, Ellen Dana Moncure and Millicent Fawcett. This group, at the South Place Ethical Society, had a national standing. She frequented the home of Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

and Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (; Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a British political activist who organised the British suffragette movement and helped women to win in 1918 the women's suffrage, right to vote in United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

on Russell Square

Russell Square is a large garden square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden, built predominantly by the firm of James Burton (property developer), James Burton. It is near the University of London's main buildings and the British Mus ...

, and Emmeline had participated in the matchgirl organisation. Besant came out on top of the poll in Tower Hamlets, with over 15,000 votes. She wrote in the ''National Reformer'':

"Ten years ago, under a cruel law, Christian bigotry robbed me of my little child. Now the care of the 763,680 children of London is placed partly in my hands."Financial constraints meant that Besant closed down both ''Our Corner'' and ''The Link'' at the end of 1888. Besant was further involved in the London dock strike of 1889. The dockers,

casual work

Contingent work, casual work, gig work or contract work, is an employment relationship with limited job security, payment on a piece work basis, typically part-time (typically with variable hours) that is considered non-permanent.

According to ...

ers who were employed by the day, were led by Ben Tillett

Benjamin Tillett (11 September 1860 – 27 January 1943) was a British socialist, trade union leader and politician. He was a leader of the "new unionism" of 1889, that focused on organizing unskilled workers. He played a major role in foundin ...

in a struggle for the "Dockers' Tanner". Besant helped Tillett draw up the union's rules and played an important part in the meetings and agitation which built up the organisation. She spoke for the dockers at public meetings and on street corners. Like the match-girls, the dockers won public support for their struggle, and the strike was won.

Theosophy

In 1889, Besant was asked to write a review for the ''Pall Mall Gazette'' on ''The Secret Doctrine

''The Secret Doctrine, the Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy'', is a pseudoscientific esoteric book as two volumes in 1888 written by Helena Blavatsky. The first volume is named ''Cosmogenesis'', the second ''Anthropogenesis''. It ...

'', a book by H. P. Blavatsky. After reading it, she sought an interview with its author, meeting Blavatsky in Paris. In this way, she was converted to Theosophy. She allowed her membership of the Fabian Society to lapse (1890) and broke her links with the Marxists.

In her ''Autobiography'', Besant follows her chapter on "Socialism" with "Through Storm to Peace", the peace of Theosophy. In 1888, she described herself as "marching toward the Theosophy" that would be the "glory" of her life. Besant had found the economic side of life lacking a spiritual dimension, so she searched for a belief based on "Love". She found this in Theosophy, so she joined the Theosophical Society, a move that distanced her from Bradlaugh and other former activist co-workers. When Blavatsky died in 1891, Besant was left as one of the leading figures in theosophy and in 1893 she represented it at the Chicago World Fair.

In 1893, soon after becoming a member of the Theosophical Society, she went to India for the first time. After a dispute the American section split away into an independent organisation. The original society, then led by Henry Steel Olcott and Besant, is today based in Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

, India, and is known as the Theosophical Society Adyar. Following the split, Besant devoted much of her energy not only to the society but also to India's freedom and progress. Besant Nagar, a neighbourhood near the Theosophical Society in Chennai, is named in her honour.

In 1893, she was a representative of The Theosophical Society at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. The World Parliament is famous in India because Indian monk Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda () (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta, was an Indian Hindus, Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figu ...

addressed the same event.

In September 1894, Besant arrived in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, where she lectured in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

and Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

. In October 1894, she wrote back to the Adyar headquarters from Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; ) is the second-most populous city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from ("fort of Edin"), the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of S ...

, New Zealand, claiming to have reformed the Theosophical Society in Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

. At the Society's Australasian convention in the same year, her followers forced William Quan Judge

William Quan Judge (April 13, 1851 – March 21, 1896) was an American mystic, esotericist, and occultist, and one of the founders of the original Theosophical Society.

Biography

Judge was born in Dublin, Ireland. When he was 13 years old, ...

to resign as vice-president; he left the Society in April 1895 together with the entire US section.

In 1895, together with the founder-president of the Theosophical Society, Henry Steel Olcott, as well as Marie Musaeus Higgins and Peter De Abrew, she was instrumental in developing the Buddhist school, Musaeus College, in Colombo on the island of Sri Lanka.

Co-freemasonry

Besant saw freemasonry, in particularCo-Freemasonry

Co-Freemasonry (or Co-Masonry) is a form of Freemasonry which admits both men and women. The first known co-masonic lodge was created 24 December 1784 as the mother lodge La Sagesse Triomphante in Lyon, France by Alessandro Cagliostro. Cagliostro ...

, as an extension of her interest in the rights of women and the greater brotherhood of man and saw co-freemasonry as a "movement which practised true brotherhood, in which women and men worked side by side for the perfecting of humanity. She immediately wanted to be admitted to this organisation", known now as the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, "Le Droit Humain".

The link was made in 1902 by the theosophist Francesca Arundale, who accompanied Besant to Paris, along with six friends. "They were all initiated, passed, and raised into the first three degrees and Annie returned to England, bearing a Charter and founded there the first Lodge of International Mixed Masonry, Le Droit Humain." Besant eventually became the Order's Most Puissant Grand Commander and was a major influence in the international growth of the Order.

President of Theosophical Society

Besant met fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater in London in April 1894. They became close co-workers in the theosophical movement and would remain so for the rest of their lives. Leadbeater claimed

Besant met fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater in London in April 1894. They became close co-workers in the theosophical movement and would remain so for the rest of their lives. Leadbeater claimed clairvoyance

Clairvoyance (; ) is the claimed ability to acquire information that would be considered impossible to get through scientifically proven sensations, thus classified as extrasensory perception, or "sixth sense". Any person who is claimed to h ...

and reputedly helped Besant become clairvoyant herself in the following year. In a letter dated 25 August 1895 to Francisca Arundale, Leadbeater narrates how Besant became clairvoyant. Together they clairvoyantly investigated the universe, matter, thought-forms, and the history of mankind, and co-authored a book called '' Occult Chemistry''.

In 1906 Leadbeater became the centre of controversy when it emerged that he had advised the practice of masturbation to some boys under his care and spiritual instruction. Leadbeater stated he had encouraged the practice to keep the boys celibate, which was considered a prerequisite for advancement on the spiritual path. Because of the controversy, he offered to resign from the Theosophical Society in 1906, which was accepted. The next year Besant became president of the society and in 1908, with her express support, Leadbeater was readmitted to the society. Leadbeater went on to face accusations of improper relations with boys, but none of the accusations were ever proven and Besant never deserted him.

Until Besant's presidency, the society had as one of its foci Theravada

''Theravāda'' (; 'School of the Elders'; ) is Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school's adherents, termed ''Theravādins'' (anglicized from Pali ''theravādī''), have preserved their version of the Buddha's teaching or ''Dharma (Buddhi ...

Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and the island of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, where Henry Olcott did the majority of his useful work. Under Besant's leadership there was more stress on the teachings of "The Aryavarta", as she called central India, as well as on esoteric Christianity.

Besant set up a new school for boys, the Central Hindu College

Banaras Hindu University (BHU), formerly Benares Hindu University, is a Collegiate university, collegiate, Central university (India), central, and Research university, research university located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, and fou ...

(CHC) at Banaras which was formed on underlying theosophical principles, and which counted many prominent theosophists in its staff and faculty. Its aim was to build a new leadership for India. The students spent 90 minutes a day in prayer and studied religious texts, but they also studied modern science. It took 3 years to raise the money for the CHC, most of which came from Indian princes. In April 1911, Besant met Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya

Madan Mohan Malaviya (25 December 1861 — 12 November 1946; ) was an Indian scholar, educational reformer and activist notable for his role in the Indian independence movement. He was president of the Indian National Congress three times and ...

and they decided to unite their forces and work for a common Hindu University at Banaras. Besant and fellow trustees of the Central Hindu College also agreed to the Government of India's precondition that the college should become a part of the new University. The Banaras Hindu University

Banaras Hindu University (BHU), formerly Benares Hindu University, is a collegiate, central, and research university located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, and founded in 1916. The university incorporated the Central Hindu College, ...

started functioning from 1 October 1917 with the Central Hindu College as its first constituent college.

Blavatsky had stated in 1889 that the main purpose of establishing the society was to prepare humanity for the future reception of a "torch-bearer of Truth", an emissary of a hidden Spiritual Hierarchy that, according to theosophists, guides the evolution of mankind. This was repeated by Besant as early as 1896; Besant came to believe in the imminent appearance of the "emissary", who was identified by theosophists as the so-called '' World Teacher''.

"World Teacher" project

In 1909, soon after Besant's assumption of the presidency, Leadbeater "discovered" fourteen-year-oldJiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti ( ; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian Philosophy, philosopher, speaker, writer, and Spirituality, spiritual figure. Adopted by members of the Theosophy, Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill ...

(1895–1986), a South Indian boy who had been living, with his father and brother, on the grounds of the headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, and declared him the probable "vehicle" for the expected " World Teacher". The "discovery" and its objective received widespread publicity and attracted a worldwide following, mainly among theosophists. It also started years of upheaval and contributed to splits in the Theosophical Society and doctrinal schisms in theosophy. Following the discovery, Jiddu Krishnamurti and his younger brother Nityananda ("Nitya") were placed under the care of theosophists and Krishnamurti was extensively groomed for his future mission as the new vehicle for the "World Teacher". Besant soon became the boys' legal guardian

A legal guardian is a person who has been appointed by a court or otherwise has the legal authority (and the corresponding duty) to make decisions relevant to the personal and property interests of another person who is deemed incompetent, ca ...

with the consent of their father, who was very poor and could not take care of them. However, his father later changed his mind and began a legal battle to regain guardianship, against the will of the boys. Early in their relationship, Krishnamurti and Besant had developed a very close bond and he considered her a surrogate mother – a role she happily accepted. (His biological mother had died when he was ten years old.)

In 1929, twenty years after his "discovery", Krishnamurti, who had grown disenchanted with the ''World Teacher Project'', repudiated the role that many theosophists expected him to fulfil. He dissolved the Order of the Star in the East, an organisation founded to assist the World Teacher in his mission, and eventually left the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

and theosophy at large. He spent the rest of his life travelling the world as an unaffiliated speaker, becoming in the process widely known as an original, independent thinker on philosophical, psychological, and spiritual subjects. His love for Besant never waned, as also was the case with Besant's feelings towards him; concerned for his wellbeing after he declared his independence, she had purchased of land near the Theosophical Society estate which later became the headquarters of the Krishnamurti Foundation India.

Home Rule movement

As early as 1902 Besant had written that "India is not ruled for the prospering of the people, but rather for the profit of her conquerors, and her sons are being treated as a conquered race." She encouraged Indian national consciousness, attackedcaste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

and child marriage, and worked effectively for Indian education. Along with her theosophical activities, Besant continued to actively participate in political matters. She had joined the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

. As the name suggested, this was originally a debating body, which met each year to consider resolutions on political issues. Mostly it demanded more of a say for middle-class Indians in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

n government. It had not yet developed into a permanent mass movement with a local organisation. About this time her co-worker Leadbeater moved to Sydney.

In 1914, World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out, and Britain asked for the support of its Empire in the fight against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. Echoing an Irish nationalist slogan, Besant declared, "England's need is India's opportunity". As editor of the '' New India'' newspaper, she attacked the colonial government of India and called for clear and decisive moves towards self-rule. As with Ireland, the government refused to discuss any changes while the war lasted.

In 1916, Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices. This was the first political party in India to have regime change as its main goal. Unlike the Congress itself, the League worked all year round. It built a structure of local branches, enabling it to mobilise demonstrations, public meetings, and agitations. In June 1917, Besant was arrested and interned at a

In 1916, Besant launched the All India Home Rule League along with Lokmanya Tilak, once again modelling demands for India on Irish nationalist practices. This was the first political party in India to have regime change as its main goal. Unlike the Congress itself, the League worked all year round. It built a structure of local branches, enabling it to mobilise demonstrations, public meetings, and agitations. In June 1917, Besant was arrested and interned at a hill station

A hill station is a touristic town located at a higher elevation than the nearby plain or valley. The English term was originally used mostly in Western imperialism in Asia, colonial Asia, but also in Africa (albeit rarely), for towns founded by ...

, where she defiantly flew a red and green flag. The Congress and the Muslim League together threatened to launch protests if she were not set free; Besant's arrest had created a focus for protest.

The government was forced to give way and to make vague but significant concessions. It was announced that the ultimate aim of British rule was Indian self-government, and moves in that direction were promised. Besant was freed in September 1917, welcomed by crowds all over India, and in December she took over as president of the Indian National Congress for a year. Both Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

and Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

spoke of Besant's influence with admiration.

After the war, a new leadership of the Indian National Congress emerged around Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

– one of those who had written to demand Besant's release. He was a lawyer who had returned from leading Asians in a peaceful struggle against racism in South Africa. Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

, Gandhi's closest collaborator, had been educated by a theosophist tutor.

The new leadership was committed to action that was both militant and non-violent, but there were differences between them and Besant. Despite her past, she was not happy with their socialist leanings. Until the end of her life, however, she continued to campaign for India's independence, not only in India but also on speaking tours of Britain. In her own version of Indian dress, she remained a striking presence on speakers' platforms. She produced a torrent of letters and articles demanding independence.

Later years and death

Besant tried as a person, theosophist, and president of the Theosophical Society, to accommodate Krishnamurti's views into her life, without success; she vowed to personally follow him in his new direction although she apparently had trouble understanding both his motives and his new message. The two remained friends until the end of her life. In 1931, she became ill in India. Besant died on 20 September 1933, at age 85, in Adyar, Madras Presidency, British India. Her body wascremated

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

.

She was survived by her daughter, Mabel. After her death, colleagues Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti ( ; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian Philosophy, philosopher, speaker, writer, and Spirituality, spiritual figure. Adopted by members of the Theosophy, Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill ...

, Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley ( ; 26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. His bibliography spans nearly 50 books, including non-fiction novel, non-fiction works, as well as essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the ...

, Guido Ferrando, and Rosalind Rajagopal, built the Happy Valley School in California, now renamed the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley in her honour.

Legacy

Widely recognized as a pioneer of women's birth control and for her contributions to the Indian freedom movement, roads have been named in her honor in the Indian citiesMumbai

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial capital and the most populous city proper of India with an estimated population of 12 ...

and Patna

Patna (; , ISO 15919, ISO: ''Paṭanā''), historically known as Pataliputra, Pāṭaliputra, is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, ...

. The Besant Road in the city of Vijayawada was named after her. In Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

, a residential neighborhood, Besant Nagar, and an urban park, the Dr. Annie Besant Park, have also been named in her honor.

The Besant Theosophical College, established in 1917, in Madanapalle is one of the oldest colleges in the Rayalaseema

Rayalaseema (IAST: ''Rāyalasīma'') is a geographic region in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It comprises four southern districts of the State, from prior to the districts reorganisation in 2022, namely Kurnool, Anantapur, Kadapa, and ...

region of Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (ISO 15919, ISO: , , AP) is a States and union territories of India, state on the East Coast of India, east coast of southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, seventh-largest state and th ...

, India. In 2023, plans were announced to upgrade this college to a university called the Annie Besant University.

Recognition in popular media

On 1 October 2015, search engine Google commemorated Annie Besant with aDoodle

A doodle is a drawing made while a person's attention is otherwise occupied. Doodles are simple drawings that can have concrete representational meaning or may just be composed of random and abstract art, abstract lines or shapes, generally w ...

on her 168th birth anniversary. Google commented: "A fierce advocate of Indian self-rule, Annie Besant loved the language, and over a lifetime of vigorous study cultivated tremendous abilities as a writer and orator. She published mountains of essays, wrote a textbook, curated anthologies of classic literature for young adults and eventually became editor of the New India newspaper, a periodical dedicated to the cause of Indian Autonomy".

In his book, ''Rebels Against the Raj'', Ramchandra Guha tells the story of how Besant and six other foreigners served India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

in its quest for independence from the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

.

Besant appears as a character in the children's novel ''Billy and the Match Girl'' by Paul Haston, about the matchgirls' strike.

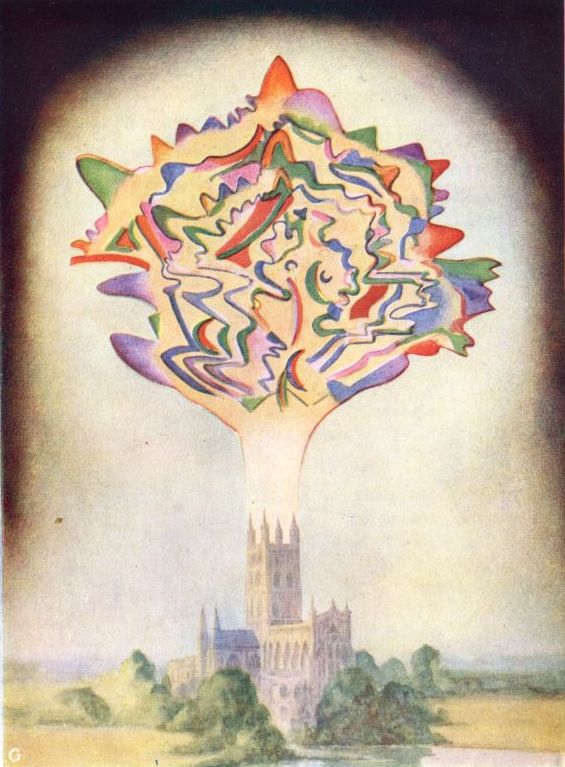

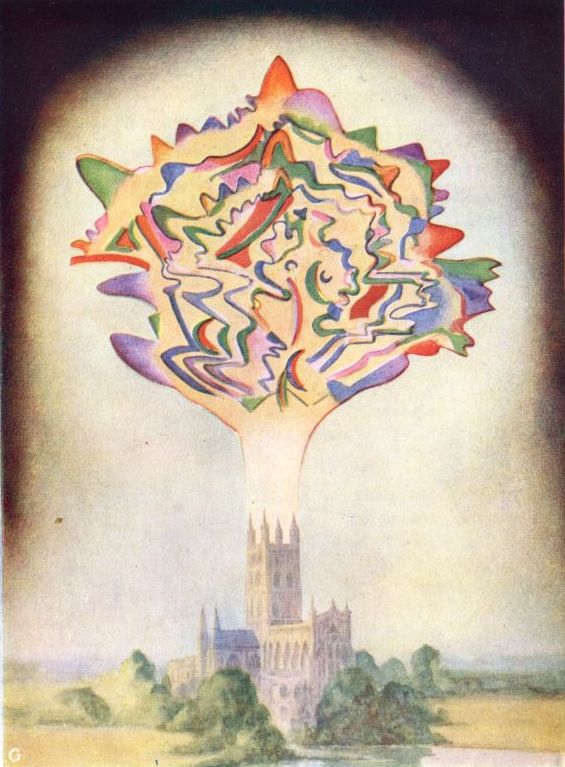

In 2016, an exhibition called ''Intention to Know'', focusing on Besant's "thought forms", was curated at the Stony Island Arts Bank, Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

.

Works

Besides being a prolific writer, Besant was a "practised stump orator" who gave sixty-six public lectures in one year. She also engaged in public debates.List of Works on Online Book

Annie Besant (Besant, Annie, 1847-1933) , The Online Books Page

br /> List of Work on Open Librar

Annie Wood Besant

* ''The Political Status of Women'' (1874)''The Political Status of Women'' (1874) was Besant's first public lecture. Carol Hanbery MacKay, ''Creative Negativity: Four Victorian Exemplars of the Female Quest'' (Stanford University, 2001), 116–117. * ''Christianity: Its Evidences, Its Origin, Its Morality, Its History'' (1876) *

The Law of Population

' (1877) *

My Path to Atheism

' (1878, 3rd ed 1885) *

Marriage, As It Was, As It Is, And As It Should Be: A Plea for Reform

' (1878) * ''Light, Heat and Sound'' (1881) *

The Atheistic Platform: 12 Lectures

' Nos. 1, 5, 9 and 12 by Besant (1884) *

Autobiographical Sketches

' (1885) *

Why I Am a Socialist

' (1886) *

Why I Became a Theosophist

' (1889) *

The Seven Principles of Man

' (1892) *

Bhagavad Gita

' (translated as ''The Lord's Song'') (1895) * ''Karma'' (1895) *

In the Outer Court

'(1895) * ''The Ancient Wisdom'' (1897) * ''Dharma'' (1898) * ''Evolution of Life and Form'' (1898) * ''Avatâras'' (1900) *

The Religious Problem in India

' (1901) *

Thought Power: Its Control and Culture

' (1901) * ''A Study in Consciousness: A contribution to the science of psychology.'' (1904) * ''Theosophy and the new psychology: A course of six lectures'' (1904) * '' Thought Forms'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1905) *

Esoteric Christianity

' (1905 2nd ed) * ''Death - and After?'' (1906) * ''Occult Chemistry'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1908

Occult chemistry;: clairvoyant observations on the chemical elements

* '' An Introduction to Yoga'' (1908

An introduction to yoga; four lectures delivered at the 32nd anniversary of the Theosophical Society, held at Benares, on Dec. 27th, 28th, 29th, 30th, 1907

*

Australian Lectures

' (1908) *

Annie Besant: An Autobiography

' (1908 2nd ed) * ''The Religious Problem in India'' Lectures on Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, Theosophy (1909

The religious problem in India: four lectures delivered during the twenty-sixth annual convention of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, Madras, 1901

* ''Man and His Bodies'' (1896, rpt 1911

* '' Elementary Lessons on Karma'' (1912) * '' A Study in Karma'' (1912) * ''Initiation: The Perfecting of Man'' (1912

Theosophy: Initiation The Perfecting of Man by Annie Besant - MahatmaCWLeadbeater.org

* ''Giordano Bruno'' (1913) * ''Man's Life in This and Other Worlds'' (1913

Man's life in this and other worlds

* ''Man: Whence, How and Whither'' with C. W. Leadbeater (1913

Man, whence, how and whither: a record of clairvoyant investigation / by Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater.

* ''Theosophy and Life's Deeper Problems'' 1916 * ''The Doctrine of the Heart'' (1920

*

The Future of Indian Politics

' 1922 * ''The Life and Teaching of Muhammad'' (1932

Annie Besant The Life And Teachings Of Muhammad ( The Prophet Of Islam)

* ''Memory and Its Nature'' (1935

* Various writings regarding

Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian-born Mysticism, mystic and writer who emigrated to the United States where she co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an internat ...

(1889–1910Blavatsky Archives contains 100s of articles on HP Blavatsky & Theosophy

* Selection of Pamphlets as follows

Pamphlets

:* "Sin and Crime" (1885) :* "God's Views on Marriage" (1890) :* "A World Without God" (1885) :* "Life, Death, and Immortality" (1886) :* "Theosophy" (1925?) :* "The World and Its God" (1886) :* "Atheism and Its Bearing on Morals" (1887) :* "On Eternal Torture" (n.d.) :* "The Fruits of Christianity" (n.d.) :* "The Jesus of the Gospels and the Influence of Christianity" (n.d.) :* "The Gospel of Christianity and the Gospel of Freethought" (1883) :* "Sins of the Church: Threatenings and Slaughters" (n.d.) :* "For the Crown and Against the Nation" (1886) :* "Christian Progress" (1890) :* "Why I Do Not Believe in God" (1887) :* "The Myth of the Resurrection" (1886) :* "The Teachings of Christianity" (1887) Indian National Movement :* The Commonweal (a weekly dealing on Indian national issues) :*New India (a daily newspaper which was a powerful mouthpiece for 15 years advocating Home Rule and revolutionizing Indian journalism)

See also

* Agni Yoga *Alice Bailey

Alice Ann Bailey (16 June 1880 – 15 December 1949) was a British and American writer. She wrote about 25 books on Theosophy and was one of the first writers to use the term New Age. She was born Alice La Trobe-Bateman, in Manchester, ...

* Benjamin Creme

* Helena Roerich

* History of feminism

* Order of the Star in the East

* Theosophy and Christianity

* Theosophy and visual arts

References

Further reading

* Briggs, Julia. ''A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit''. New Amsterdam Books, 2000, 68, 81–82, 92–96, 135–139 * Chandrasekhar, S. ''A Dirty, Filthy Book: The Writing of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant on Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control and an Account of the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial''. University of California Berkeley 1981 * Grover, Verinder and Ranjana Arora (eds.) ''Annie Besant: Great Women of Modern India – 1'': Published by Deep of Deep Publications, New Delhi, India, 1993 * Kumar, Raj Rameshwari Devi and Romila Pruthi. ''Annie Besant: Founder of Home Rule Movement'', Pointer Publishers, 2003 * Kumar, Raj, ''Annie Besant's Rise to Power in Indian Politics, 1914–1917''. Concept Publishing, 1981 * Manvell, Roger. ''The trial of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh''. Elek, London 1976 * Nethercot, Arthur H. ''The first five lives of Annie Besant'' Hart-Davis: London, 1961 * Nethercot, Arthur H. ''The last four lives of Annie Besant'' Hart-Davis: London (also University of Chicago Press 1963) * Taylor, Anne. ''Annie Besant: A Biography'', Oxford University Press, 1991 (also US edition 1992) * Uglow, Jennifer S., Maggy Hendry, ''The Northeastern Dictionary of Women's Biography''. Northeastern University, 1999External links

Annie Besant

Biography a

varanasi.org.in

* ttp://www.alpheus.org/html/articles/theosophy/bevir3.html Annie Besant's Quest for Truth: Christianity, Secularism, and New Age Thought*Framke, Maria

Besant, Annie

in

* * ttps://www.freemasonryformenandwomen.co.uk/ The British Federation of the International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, Le Droit Humain, founded by Annie Besant in 1902br>The International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women, Le Droit Humain

Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. *

William Thomas Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was an English newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst e ...

"Character Sketch: October of Mrs. Annie Besant" 349–367 in ''Review of Reviews'' IV:22, October 1891.