Andrea Vesalius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited to become imperial physician to the court of

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited to become imperial physician to the court of

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the book ''

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the book '' Besides the first good description of the

Besides the first good description of the

File:Vesalius Fabrica p174.jpg

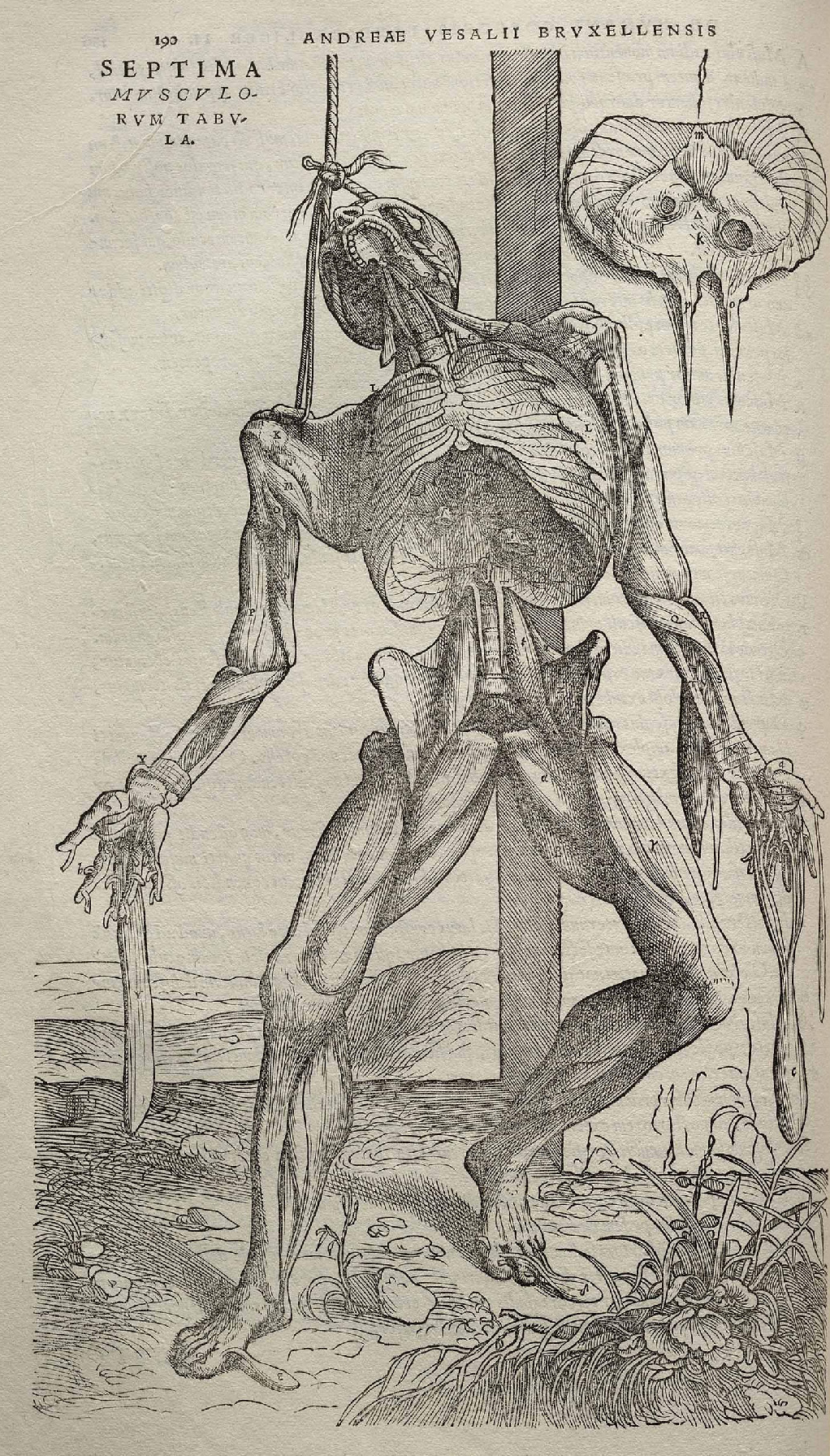

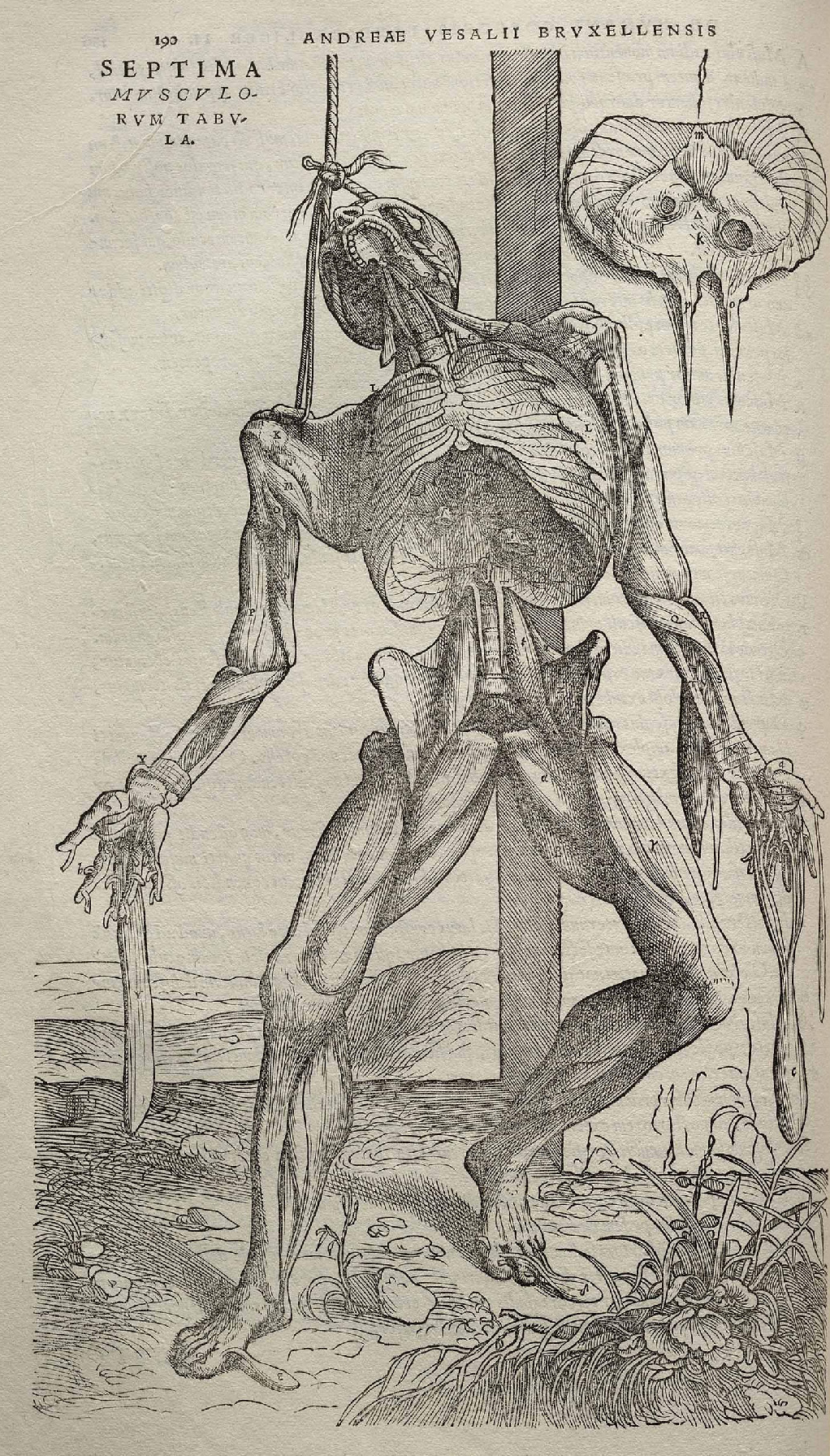

File:Vesalius Fabrica p194.jpg

File:De humani corporis fabrica (27).jpg

File:Vesalius Fabrica p178.jpg

* Vesalius believed the

* Vesalius believed the

Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, Dе humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basileae 1543

Anatomia 1522–1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Bibliography van Andreas Vesalius

* ttp://himetop.wikidot.com/andreas-vesalius Places and memories related to Andreas Vesalius

Play on Vesalius

Translating Vesalius

Ars Anatomica collection at University of Edinburgh image service (includes Vesalius's ''De Humanis Corporis Fabrica'')

a virtual copy of Vesalius's ''De Humanis Corporis Fabrica''. From the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome

coloured and complete with manekin at

Medic@

Vesalius four centuries later

by John F. Fulton. Logan Clendening lecture on the history and philosophy of medicine, University of Kansas, 1950. Full-text PDF. * Andreas Vesalius

''VESALIUS project''

. Information about the new DVD "De Humani Corporis Fabrica" produced by Health Science Library of the St. Anna Hospital in Ferrara – Italy.

Vesalius College in Brussels

TV report on 500th birthday Vesalius by tvbrussel

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem''

(1543) – full digital facsimile at

Vesalius at 500

– digital exhibition from the

anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

who wrote ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, "On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history of a ...

'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ''in seven books''), which is considered one of the most influential books on human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

and a major advance over the long-dominant work of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

. Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

. He was born in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

. He was a professor at the University of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

(1537–1542) and later became Imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) fr ...

.

Early life and education

Vesalius was born as Andries van Wesel to his father Anders van Wesel and mother Isabel Crabbe on 31 December 1514 in Brussels, which was then part of theHabsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

. His great-grandfather, Jan van Wesel, probably born in Wesel

Wesel () is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, in western Germany. It is the capital of the Wesel (district), Wesel district.

Geography

Wesel is situated at the confluence of the Lippe River and the Rhine.

Division of the city

Suburbs of Wesel i ...

, received a medical degree from the University of Pavia

The University of Pavia (, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; ) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one of the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest un ...

and taught medicine at the University of Leuven. His grandfather, Everard van Wesel, was the Royal Physician of Emperor Maximilian, whilst his father, Anders van Wesel, served as apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is an Early Modern English, archaic English term for a medicine, medical professional who formulates and dispenses ''materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in Brit ...

to Maximilian and later valet de chambre

''Valet de chambre'' (), or ''varlet de chambre'', was a court appointment introduced in the late Middle Ages, common from the 14th century onwards. Royal households had many persons appointed at any time. While some valets simply waited on ...

to his successor, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

. Anders encouraged his son to continue in the family tradition and enrolled him in the Brethren of the Common Life

The Brethren of the Common Life (, FVC) was a Roman Catholic pietist religious community founded in the Netherlands in the 14th century by Gerard Groote, formerly a successful and worldly educator who had had a religious experience and preached a ...

in Brussels to learn Greek and Latin prior to learning medicine, according to standards of the era.

In 1528 Vesalius entered the University of Leuven (''Pedagogium Castrense'') taking arts, but when his father was appointed as the Valet de Chambre in 1532 he decided instead to pursue a career in medicine at the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, where he moved in 1533. There he studied the theories of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

under the auspices of Johann Winter von Andernach

Johann Winter von Andernach (born Johann Winter; 1505 – 4 October 1574) was a German Renaissance physician, university professor, humanist, translator of ancient, mostly medical works, and writer of his own medical, philological and humanities w ...

, Jacques Dubois

Jacques Dubois ( Latinised as Jacobus Sylvius; 1478 – 14 January 1555) was a French anatomist. Dubois was the first to describe venous valves, although their function was later discovered by William Harvey. He was the brother of Franciscus Sy ...

(Jacobus Sylvius) and Jean Fernel

Jean François Fernel ( Latinized as Ioannes Fernelius; 1497 – 26 April 1558) was a French physician who introduced the term "physiology" to describe the study of the body's function. He was the first person to describe the spinal canal. The ...

. It was during that time that he developed an interest in anatomy and was often found examining excavated bones in the charnel house

A charnel house is a vault or building where human skeletal remains are stored. They are often built near churches for depositing bones that are unearthed while digging graves. The term can also be used more generally as a description of a plac ...

s at the Cemetery of the Innocents. He is said to have constructed his first skeleton by stealing from a gibbet

Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of criminals were hanged on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. Occasionally, the gibbet () was also used as a method of public ex ...

.

Vesalius was forced to leave Paris in 1536 owing to the opening of hostilities between the Holy Roman Empire and France and returned to the University of Leuven. He completed his studies there and graduated the following year. His doctoral thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

, ''Paraphrasis in nonum librum Rhazae medici Arabis clarissimi ad regem Almansorem, de affectuum singularum corporis partium curatione'', was a commentary on the ninth book of Rhazes

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, also known as Rhazes (full name: ), , was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, and a ...

.

Medical career and accomplishments

On the day of his graduation he was immediately offered the chair of surgery and anatomy (''explicator chirurgiae'') at theUniversity of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

. He also guest-lectured at the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

and the University of Pisa

The University of Pisa (, UniPi) is a public university, public research university in Pisa, Italy. Founded in 1343, it is one of the oldest universities in Europe. Together with Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa and Sant'Anna School of Advanced S ...

. Prior to taking up his position in Padua, Vesalius traveled through Italy and assisted the future Pope Paul IV

Pope Paul IV (; ; 28 June 1476 – 18 August 1559), born Gian Pietro Carafa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 May 1555 to his death, in August 1559. While serving as papal nuncio in Spain, he developed ...

and Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

to heal those afflicted by leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a Chronic condition, long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the Peripheral nervous system, nerves, respir ...

. In Venice he met the illustrator Johan van Calcar, a student of Titian. It was with van Calcar that Vesalius published his first anatomical text, ''Tabulae Anatomicae Sex'', in 1538. Previously these topics had been taught primarily from reading classical texts, mainly Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

, followed by an animal dissection by a barber–surgeon whose work was directed by the lecturer. No attempt was made to confirm Galen's claims, which were considered unassailable. Vesalius, in contrast, performed dissection as the primary teaching tool, handling the actual work himself and urging students to perform dissection themselves. He considered hands-on direct observation to be the only reliable resource.

Vesalius created detailed illustrations of anatomy for students in the form of six large woodcut posters. When he found that some of them were being widely copied, he published them all in 1538 under the title ''Tabulae anatomicae sex''. He followed this in 1539 with an updated version of Winter's anatomical handbook, ''Institutiones anatomicae.''

In 1539 he also published his ''Venesection Epistle'' on bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) was the deliberate withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and othe ...

. This was a popular treatment for almost any illness, but there was some debate about where to take the blood from. The classical Greek procedure, advocated by Galen, was to collect blood from a site near the location of the illness. However the Muslim and medieval practice was to draw a smaller amount of blood from a distant location. Vesalius' pamphlet generally supported Galen's view but with qualifications that rejected the infiltration of Galen.

In Bologna, Vesalius discovered that all of Galen's research was restricted to animals, since the tradition of Rome did not allow dissection of the human body. Galen had dissected Barbary macaque

The Barbary macaque (''Macaca sylvanus''), also known as Barbary ape, is a macaque species native to the Atlas Mountains of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, along with a small introduced population in Gibraltar.

It is the type species of the genus ' ...

s instead, which he considered structurally closest to man. Even though Galen was a qualified examiner, his research produced many errors owing to the limited anatomical material available to him. Vesalius contributed to the new Giunta edition of Galen's collected works and began to write his own anatomical text based on his own research. Until Vesalius pointed out Galen's substitution of animal for human anatomy, it had gone unnoticed and had long been the basis of studying human anatomy.

Unlike Galen, Vesalius was able to procure a steady supply of human cadavers for dissection. In 1539, a judge at the Padua criminal court had been interested by Vesalius' work and had agreed to regularly supply him the cadavers of executed criminals.

Galen had assumed that arteries carried the purest blood to higher organs such as the brain and lungs from the left ventricle of the heart, while veins carried blood to the lesser organs such as the stomach from the right ventricle. In order for this theory to be correct, some kind of opening was needed to interconnect the ventricles, and Galen claimed to have found them. So paramount was Galen's authority that for 1400 years a succession of anatomists had claimed to find these holes, until Vesalius admitted he could not find them. Nonetheless, he did not venture to dispute Galen on the distribution of blood, being unable to offer any other solution, and so supposed that it diffused through the unbroken partition between the ventricles.

Other famous examples of Vesalius disproving Galen's assertions were his discoveries that the lower jaw (mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

) was composed of only one bone, not two (which Galen had assumed based on animal dissection) and that humans lack the rete mirabile

A rete mirabile (Latin for "wonderful net"; : retia mirabilia) is a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other, found in some vertebrates, mainly warm-blooded ones. The rete mirabile utilizes countercurrent blood flow within the ...

, a network of blood vessels at the base of the brain that is found in sheep and other ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to b ...

.

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. He assembled and articulated the bones, finally donating the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

to the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

. This preparation ("The Basel Skeleton") is Vesalius' only well-preserved skeletal preparation, and also the world's oldest surviving anatomical preparation. It is still displayed at the Anatomical Museum of the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

.

In the same year Vesalius took residence in Basel to help Johannes Oporinus publish the seven-volume ''De humani corporis fabrica

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, "On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history of a ...

'' (''On the fabric of the human body''), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

that he dedicated to Charles V. Many believe it was illustrated by Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar, but evidence is lacking, and it is unlikely that a single artist created all 273 illustrations in a period of time so short. At about the same time he published an abridged edition for students, ''Andrea Vesalii suorum de humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome'', and dedicated it to Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, the son of the Emperor. That work, now collectively referred to as the Fabrica of Vesalius, was groundbreaking in the history of medical publishing and is considered to be a major step in the development of scientific medicine. Because of this, it marks the establishment of anatomy as a modern descriptive science.

Though Vesalius' work was not the first such work based on actual dissection, nor even the first work of this era, the production quality, highly detailed and intricate plates, and the likelihood that the artists who produced it were clearly present in person at the dissections made it an instant classic. Pirated editions were available almost immediately, an event Vesalius acknowledged in a printer's note would happen. Vesalius was 28 years old when the first edition of ''Fabrica'' was published.

Imperial physician and death

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited to become imperial physician to the court of

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited to become imperial physician to the court of Emperor Charles V

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) fr ...

. He informed the Venetian Senate

The Senate (), formally the ''Consiglio dei Pregadi'' or ''Rogati'' (, ), was the main deliberative and legislative body of the Republic of Venice.

Establishment

The Venetian Senate was founded in 1229, or less likely shortly before that date. ...

that he would leave his post at Padua, which prompted Duke Cosimo I de' Medici to invite him to move to the expanding university in Pisa, which he declined. Vesalius took up the offered position in the imperial court, where he had to deal with other physicians who mocked him for being a mere barber surgeon

The barber surgeon was one of the most common European medical practitioners of the Middle Ages, generally charged with caring for soldiers during and after battle. In this era, surgery was seldom conducted by physicians. Instead, barbers, who ...

instead of an academic working on the respected basis of theory.

In the 1540s, shortly after entering in service of the emperor, Vesalius married Anne van Hamme, from Vilvorde, Belgium. They had one daughter, named Anne, who died in 1588.

Over the next eleven years Vesalius traveled with the court, treating injuries caused in battle or tournaments, performing postmortems, administering medication, and writing private letters addressing specific medical questions. During these years he also wrote ''the Epistle on the China root'', a short text on the properties of a medical plant whose efficacy he doubted, as well as a defense of his anatomical findings. This elicited a new round of attacks on his work that called for him to be punished by the emperor. In 1551, Charles V commissioned an inquiry in Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

to investigate the religious implications of his methods. Although Vesalius' work was cleared by the board, the attacks continued. Four years later one of his main detractors and one-time professors, Jacobus Sylvius, published an article that claimed that the human body itself had changed since Galen had studied it.

In 1555, Vesalius became physician to Philip II, and in the same year he published a revised edition of ''De humani corporis fabrica''.

In 1564 Vesalius went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, some said, in penance after being accused of dissecting a living body. He sailed with the Venetian fleet under James Malatesta via Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. When he reached Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

he received a message from the Venetian senate requesting him again to accept the Paduan professorship, which had become vacant on the death of contemporary Fallopius.

After struggling for many days with adverse winds in the Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

, he was shipwrecked on the island of Zakynthos

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; ; ) or Zante (, , ; ; from the Venetian language, Venetian form, traditionally Latinized as Zacynthus) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an are ...

. Here he soon died, in such debt that a benefactor kindly paid for his funeral. At the time of his death he was 49 years old. He was buried somewhere on the island of Zakynthos (Zante).

For some time, it was assumed that Vesalius's pilgrimage was due to the pressures imposed on him by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

. Today, this assumption is generally considered to be without foundation and is dismissed by modern biographers. It appears the story was spread by Hubert Languet

Hubert Languet (1518 – 30 September 1581, in Antwerp) was a French diplomat and reformer. The leading idea of his diplomacy was that of religious and civil liberty for the protection and expansion of Protestantism. He did everything in his pow ...

, a diplomat under Emperor Charles V and then under the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by the stadtholders of, and then the heirs apparent of ...

, who claimed in 1565 that Vesalius had performed an autopsy on an aristocrat in Spain while the heart was still beating, leading to the Inquisition's condemning him to death. The story went on to claim that Philip II had the sentence commuted to a pilgrimage. That story re-surfaced several times, until it was more recently revised.

The decision to undertake the pilgrimage was likely just a pretext to leave the Spanish court. Its lifestyle did not please him and he longed to continue his research. Given that he could not get rid of his royal service by resignation, he managed to escape asking for the permission to go to Jerusalem.

Publications

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica''

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the book ''

In 1543, Vesalius asked Johannes Oporinus to publish the book ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, "On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history of a ...

'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ''in seven books''), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

he dedicated to Charles V and which many believe was illustrated by Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar.

About the same time he published another version of his great work, entitled ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Librorum Epitome'' (''Abridgement of the On the fabric of the human body'') more commonly known as the ''Epitome'', with a stronger focus on illustrations than on text, so as to help readers, including medical students, to easily understand his findings. The actual text of the ''Epitome'' was an abridged form of his work in the ''Fabrica'', and the organization of the two books was quite varied. He dedicated it to Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, son of the Emperor.

The ''Fabrica'' emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as a result of an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. His book contains drawings of several organs on two leaves. This allows for the creation of three-dimensional diagrams by cutting out the organs and pasting them on flayed figures. This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously, which had strong Galenic/Aristotelean elements, as well as elements of astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

. Although modern anatomical texts had been published by Mondino Mondino is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Diana Mondino (born 1958), Argentine politician

* Eduardo Mondino (born 1958), Argentine politician

* Jean-Baptiste Mondino (born 1949), French photographer

* Mahaut Mondi ...

and Berenger, much of their work was clouded by reverence for Galen and Arabian doctrines.

Besides the first good description of the

Besides the first good description of the sphenoid bone

The sphenoid bone is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of occipital bone, basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bon ...

, he showed that the sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

consists of three portions and the sacrum

The sacrum (: sacra or sacrums), in human anatomy, is a triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part of the pelvic cavity, ...

of five or six, and described accurately the vestibule in the interior of the temporal bone

The temporal bone is a paired bone situated at the sides and base of the skull, lateral to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples where four of the cranial bone ...

. He not only verified Estienne's observations on the valves of the hepatic veins

In human anatomy, the hepatic veins are the veins that drain venous blood from the liver into the inferior vena cava (as opposed to the hepatic portal vein which conveys blood from the gastrointestinal organs to the liver). There are usually thr ...

, but also described the vena azygos

The azygos vein (from Ancient Greek ἄζυγος (ázugos), meaning 'unwedded' or 'unpaired') is a vein running up the right side of the thoracic vertebral column draining itself towards the superior vena cava. It connects the systems of superio ...

, and discovered the canal which passes in the fetus between the umbilical vein and the vena cava, since named the ductus venosus

In the fetus, the ''ductus venosus'' (''"DV"''; Arantius' duct after Julius Caesar Aranzi) shunts a portion of umbilical vein blood flow directly to the inferior vena cava. Thus, it allows oxygenated blood from the placenta to bypass the liver. ...

. He described the omentum and its connections with the stomach, the spleen

The spleen (, from Ancient Greek '' σπλήν'', splḗn) is an organ (biology), organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter.

The spleen plays important roles in reg ...

and the colon; gave the first correct views of the structure of the pylorus

The pylorus ( or ) connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pyloric canal'' ends a ...

; observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man; gave the first good account of the mediastinum

The mediastinum (from ;: mediastina) is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is a region that contains vital organs and structures within the thorax, mainly the heart and its vessels, the eso ...

and pleura

The pleurae (: pleura) are the two flattened closed sacs filled with pleural fluid, each ensheathing each lung and lining their surrounding tissues, locally appearing as two opposing layers of serous membrane separating the lungs from the med ...

and the fullest description of the anatomy of the brain up to that time. He did not understand the inferior recesses, and his account of the nerves is confused by regarding the optic as the first pair, the third as the fifth, and the fifth as the seventh.

In this work, Vesalius also becomes the first person to describe mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation or assisted ventilation is the Medicine, medical term for using a ventilator, ventilator machine to fully or partially provide artificial ventilation. Mechanical ventilation helps move air into and out of the lungs, wit ...

.Vallejo-Manzur F. et al. (2003) "The resuscitation greats. Andreas Vesalius, the concept of an artificial airway." "Resuscitation" 56:3–7 It is largely this achievement that has resulted in Vesalius being incorporated into the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists

The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) is responsible for examining and qualifying anaesthetists in Australia and New Zealand. The College maintains standards of practice in anaesthesia.

Membership

The College has app ...

college arms and crest.

Excerpts

When I undertake the dissection of a human pelvis I pass a stout rope tied like a noose beneath the lower jaw and through the zygomas up to the top of the head... The lower end of the noose I run through a pulley fixed to a beam in the room so that I may raise or lower the cadaver as it hangs there or turn around in any direction to suit my purpose; ... You must take care not to put the noose around the neck, unless some of the muscles connected to theoccipital bone The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...have already been cut away.

Other publications

In 1538, Vesalius wrote ''Epistola, docens venam axillarem dextri cubiti in dolore laterali secandam'' (''A letter, teaching that in cases of pain in the side, the axillary vein of the right elbow be cut''), commonly known as the Venesection Letter, which demonstrated a revivedvenesection

In medicine, venipuncture or venepuncture is the process of obtaining intravenous access for the purpose of venous blood sampling (also called ''phlebotomy'') or intravenous therapy. In healthcare, this procedure is performed by medical labor ...

, a classical procedure in which blood was drawn near the site of the ailment. He sought to locate the precise site for venesection in pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

within the framework of the classical method. The real significance of the book is his attempt to support his arguments by the location and continuity of the venous system

Veins () are blood vessels in the circulatory system of humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are those of the pulmonary and fetal c ...

from his observations rather than appeal to earlier published works. With this novel approach to the problem of venesection, Vesalius posed the then striking hypothesis that anatomical dissection might be used to test speculation.

In 1546, three years after the ''Fabrica'', he wrote his ''Epistola rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chynae decocti'', commonly known as the Epistle on the China Root. Ostensibly an appraisal of a popular but ineffective treatment for gout, syphilis, and stones

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, this work is especially important as a continued polemic against Galenism and a reply to critics in the camp of his former professor Jacobus Sylvius, now an obsessive detractor.

In February 1561, Vesalius was given a copy of Gabriele Fallopio's ''Observationes anatomicae'', friendly additions and corrections to the Fabrica. Before the end of the year Vesalius composed a cordial reply, ''Anatomicarum Gabrielis Fallopii observationum examen'', generally referred to as the ''Examen''. In this work he recognizes in Fallopio a true equal in the science of dissection he had done so much to create. Vesalius' reply to Fallopio was published in May 1564, a month after Vesalius' death on the Greek island of Zante

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; ; ) or Zante (, , ; ; from the Venetian form, traditionally Latinized as Zacynthus) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an area of , and a coastline in ...

(now called Zakynthos

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; ; ) or Zante (, , ; ; from the Venetian language, Venetian form, traditionally Latinized as Zacynthus) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an are ...

).

Scientific findings

Skeletal system

* Vesalius believed the

* Vesalius believed the skeletal system

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

to be the framework of the human body. It was in this opening chapter or book of ''De fabrica'' that Vesalius made several of his strongest claims against Galen's theories and writings which he had put in his anatomy books. In his extensive study of the skull, Vesalius claimed that the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

consisted of one bone, whereas Galen had thought it to be two separate bones. He accurately described the vestibule in the interior of the temporal bone

The temporal bone is a paired bone situated at the sides and base of the skull, lateral to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples where four of the cranial bone ...

of the skull.

* In Galen's observation of the ape, he had discovered that their sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

consisted of seven parts which he assumed also held true for humans. Vesalius discovered that the human sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bloo ...

consisted of only three parts.

* He also disproved the common belief that men had one rib fewer than women and noted that the fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

and tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

bones of the leg were indeed larger than the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

bone of the arm, unlike Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

's original findings.

Muscular system

* One of Vesalius' contributions to the study of themuscular system

The muscular system is an organ (anatomy), organ system consisting of skeletal muscle, skeletal, smooth muscle, smooth, and cardiac muscle, cardiac muscle. It permits movement of the body, maintains posture, and circulates blood throughout the bo ...

is the illustrations that accompany the text in ''De fabrica'', which would become known as the "muscle men". He describes the source and position of each muscle of the body and provides information on their respective operation.

Vascular and circulatory systems

* Vesalius' work on thevascular Vascular can refer to:

* blood vessels, the vascular system in animals

* vascular tissue

Vascular tissue is a complex transporting tissue, formed of more than one cell type, found in vascular plants. The primary components of vascular tissue ...

and circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart ...

s was his greatest contribution to modern medicine. In his dissections of the heart, Vesalius became convinced that Galen's claims of a porous interventricular septum

The interventricular septum (IVS, or ventricular septum, or during development septum inferius) is the stout wall separating the ventricle (heart), ventricles, the lower chambers of the heart, from one another.

The interventricular septum is di ...

were false. This fact was previously described by Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus (; ; ; also known as ''Michel Servetus'', ''Miguel de Villanueva'', ''Revés'', or ''Michel de Villeneuve''; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and Renaissance ...

, a fellow of Vesalius, but never reached the public, for it was written down in the "Manuscript of Paris", in 1546, and published later in his ''Christianismi Restitutio'' (1553), a book regarded as heretical by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

. Only three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades, the rest having been burned shortly after publication. In the second edition Vesalius published that the septum was indeed waterproof, discovering (and naming), the mitral valve

The mitral valve ( ), also known as the bicuspid valve or left atrioventricular valve, is one of the four heart valves. It has two Cusps of heart valves, cusps or flaps and lies between the atrium (heart), left atrium and the ventricle (heart), ...

to explain the blood flow.

* Vesalius believed that cardiac systole is synchronous with the arterial pulse.

* He not only verified Estienne's findings on the valves of the hepatic veins

In human anatomy, the hepatic veins are the veins that drain venous blood from the liver into the inferior vena cava (as opposed to the hepatic portal vein which conveys blood from the gastrointestinal organs to the liver). There are usually thr ...

, but also described the azygos vein

The azygos vein (from Ancient Greek ἄζυγος (ázugos), meaning 'unwedded' or 'unpaired') is a vein running up the right side of the thoracic vertebral column draining itself towards the superior vena cava. It connects the systems of superio ...

, and discovered the canal which passes into the fetus between the umbilical vein

The umbilical vein is a vein present during fetal development that carries oxygenated blood from the placenta into the growing fetus. The umbilical vein provides convenient access to the central circulation of a neonate for restoration of blood vo ...

and vena cava

In anatomy, the ''venae cavae'' (; ''vena cava'' ; ) are two large veins ( great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into t ...

.

Nervous system

* Vesalius defined a nerve as the mode of transmitting sensation and motion and thus refuted his contemporaries' claims thatligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

s, tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue, dense fibrous connective tissue that connects skeletal muscle, muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tensi ...

s and aponeuroses

An aponeurosis (; : aponeuroses) is a flattened tendon by which muscle attaches to bone or fascia. Aponeuroses exhibit an ordered arrangement of collagen fibres, thus attaining high tensile strength in a particular direction while being vulnerable ...

were three types of nerve units.

* He believed that the brain and the nervous system are the center of the mind and emotion in contrast to the common Aristotelian belief that the heart was the center of the body. He correspondingly believed that nerves themselves do not originate from the heart, but from the brain—facts already experimentally proved by Herophilus

Herophilos (; ; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first scientist to systematically p ...

and Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; ; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where they carried out anatomical research ...

in the classical era, but suppressed after the adoption of Aristotelianism by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages.

* Upon studying the optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual system, visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve i ...

, Vesalius came to the conclusion that nerves were not hollow.

Abdominal organs

* In ''De fabrica'', he corrected an earlier claim he made in ''Tabulae'' about the right kidney being set higher than the left. Vesalius claimed that the kidneys were not a filter device for urine to pass through, but rather that the kidneys serve to filter blood as well, and that excretions from the kidneys travelled through theureters

The ureters are tubes composed of smooth muscle that transport urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. In an adult human, the ureters typically measure 20 to 30 centimeters in length and about 3 to 4 millimeters in diameter. They are lin ...

to the bladder.

* He described the omentum, and its connections with the stomach, the spleen and the colon gave the first correct views of the structure of the pylorus

The pylorus ( or ) connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pyloric canal'' ends a ...

.

* He also observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man and gave the first good account of the mediastinum

The mediastinum (from ;: mediastina) is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is a region that contains vital organs and structures within the thorax, mainly the heart and its vessels, the eso ...

and pleura

The pleurae (: pleura) are the two flattened closed sacs filled with pleural fluid, each ensheathing each lung and lining their surrounding tissues, locally appearing as two opposing layers of serous membrane separating the lungs from the med ...

.

* Vesalius admitted that due to a lack of pregnant cadavers he was unable to come to a significant understanding of the reproductive organs. However, he did find that the uterus had been falsely identified as having two distinct sections.

Heart

* Through his work with muscles, Vesalius believed that a criterion for muscles was their voluntary motion. On this claim, he deduced that the heart was not a true muscle due to the obvious involuntary nature of its motion. * He identified two chambers and two atria. Theright atrium

The atrium (; : atria) is one of the two upper chambers in the heart that receives blood from the circulatory system. The blood in the atria is pumped into the heart ventricles through the atrioventricular mitral and tricuspid heart valves.

...

was considered a continuation of the inferior and superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

* Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lak ...

venae cavae

In anatomy, the ''venae cavae'' (; ''vena cava'' ; ) are two large veins (great vessels) that return deoxygenated blood from the body into the heart. In humans they are the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, and both empty into the ...

, and the left atrium

The atrium (; : atria) is one of the two upper chambers in the heart that receives blood from the circulatory system. The blood in the atria is pumped into the heart ventricles through the atrioventricular mitral and tricuspid heart valves.

...

was considered a continuation of the pulmonary vein

The pulmonary veins are the veins that transfer Blood#Oxygen transport, oxygenated blood from the lungs to the heart. The largest pulmonary veins are the four ''main pulmonary veins'', two from each lung that drain into the left atrium of the h ...

.

* He also addressed the controversial issue of the heart being the centre of the soul. He wished to avoid drawing any conclusions due to possible conflict with contemporary religious beliefs.

* Against Galen's theory and many beliefs he also discovered that there was no hole in the septum

In biology, a septum (Latin language, Latin for ''something that encloses''; septa) is a wall, dividing a Body cavity, cavity or structure into smaller ones. A cavity or structure divided in this way may be referred to as septate.

Examples

Hum ...

or heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

.

Other achievements

* Vesalius disproved Galen's assertion that men have more teeth than women. * Vesalius introduced the notion of induction of the extraction ofempyema

An empyema (; ) is a collection or gathering of pus within a naturally existing anatomical cavity. The term is most commonly used to refer to pleural empyema, which is empyema of the pleural cavity. It is similar or the same in meaning as an a ...

through surgical means.

* Due to his study of the human skull and the variations in its features he is said to have been responsible for the launch of the study of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

.

* Vesalius always encouraged his students to check their findings, and even his own findings, so that they could better understand the structure of the human body.

* In addition to his continual efforts to study anatomy he also worked on medicinal remedies and came to such conclusions as treating syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

with chinaroot.

* Vesalius claimed that medicine had three aspects: drugs, diet, and 'the use of hands'—mainly suggesting surgery and the knowledge of anatomy and physiology gained through dissection.

* Vesalius was a supporter of 'parallel dissections' in which an animal cadaver and a human cadaver are dissected simultaneously in order to demonstrate the anatomical differences and thus correct Galenic errors.

Scientific and historical impact

The influence of Vesalius' plates representing the partial dissections of the human figure posing in a landscape setting is apparent in the anatomical plates prepared by the Baroque painterPietro da Cortona

Pietro da Cortona (; 1 November 1596 or 159716 May 1669) was an Italian Baroque painter and architect. Along with his contemporaries and rivals Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, he was one of the key figures in the emergence of Roman ...

(1596–1669), who executed anatomical plates with figures in dramatic poses, most of them with architectural or landscape backdrops.

In 1844, botanists Martin Martens

Martin Martens (8 December 1797 – 8 February 1863) was a Belgian botanist and chemist born in Maastricht, Netherlands.

He studied medicine in Liège, afterwards serving as a physician in Maastricht from 1823 to 1835. From 1835 to 1863 he was ...

and Henri Guillaume Galeotti

Henri Guillaume Galeotti (10 September 1814 – 1858) was a French-Belgian botanist and geologist of Italian parentage born in Paris. He specialized in the study of the family Cactaceae.

He studied geology and natural history at the ''Etablissemen ...

published ''Vesalea

''Vesalea'' is a plant genus in the honeysuckle family Caprifoliaceae. They are native to Mexico.

The genus was circumscribed by Martin Martens and Henri Guillaume Galeotti in Bull. Acad. Roy. Sci. Bruxelles vol.11 (1) on page 242 in 1844.

The ...

'', which is a plant genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

in the honeysuckle family Caprifoliaceae

The Caprifoliaceae or honeysuckle family is a clade of dicotyledonous flowering plants consisting of about 860 species in 33 to 42 genera, with a nearly cosmopolitan distribution. Centres of diversity are found in eastern North America and easte ...

and it was named in Vesalius's honour.

See also

* Androtomy * '' Brain Renaissance'' *InVesalius

InVesalius is a free medical software used to generate virtual reconstructions of structures in the human body. Based on two-dimensional images, acquired using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging equipment, the software generates v ...

* Medical Renaissance

The Medical Renaissance, from around 1400 to 1700, was a period of progress in European medical knowledge, with renewed interest in the ideas of the ancient Greek, Roman civilizations and Islamic medicine, following the translation into Mediev ...

* Physician writer

Physician writers are physicians who write creatively in fields outside their practice of medicine.

The following is a partial list of physician-writers by historic epoch or century in which the author was born, or published their first non-medic ...

* Timeline of medicine and medical technology

This is a timeline of the history of medicine and medical technology.

Antiquity

* 3300 BC – During the Stone Age, early doctors used very primitive forms of herbal medicine in India.

* 3000 BC – Ayurveda The origins of Ayurveda have been ...

* Vesalius College

Vesalius College, also known as VeCo, is a private college located in Brussels, Belgium. Founded in 1987, it is named after Andreas Vesalius, a pioneering anatomist of the Renaissance period.

The college is associated with the Vrije Universitei ...

Notes

References

Sources

* Dear, Peter. ''Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and Its Ambitions, 1500–1700''. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001. * Debus, Allen, ed. ''Vesalius''. ''Who's Who in the World of Science: From Antiquity to Present''. 1st ed. Hanibal: Western Co., 1968. * * Porter, Roy, ed. ''Vesalius''. ''The Biographical Dictionary of Scientists''. 2nd Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. * Saunders, JB de CM and O'Malley, Charles D. ''The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels''. New York: Dover, 1973eprint

In academic publishing, an eprint or e-print is a digital version of a research document (usually a journal article, but could also be a thesis, conference paper, book chapter, or a book) that is accessible online, usually as green open access, ...

* "Vesalius." Encyclopedia Americana. 1992.

* Vesalius, Andreas. ''On the Fabric of the Human Body,'' translated by W. F. Richardson and J. B. Carman. 5 vols. San Francisco and Novato: Norman Publishing, 1998–2009. ''The Fabric of the human Body,'' Translated by Daniel H. Garrison and Malcolm H. Hast. Basel: Karger Publishing, 2013. Garrison, Daniel H. Vesalius: ''The China Root Epistle. A New Translation and Critical Edition.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

* Williams, Trevor, ed. ''Vesalius''. ''A Biographical Dictionary of Scientists''. 3rd Ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1982.

External links

Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, Dе humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basileae 1543

Anatomia 1522–1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Bibliography van Andreas Vesalius

* ttp://himetop.wikidot.com/andreas-vesalius Places and memories related to Andreas Vesalius

Play on Vesalius

Translating Vesalius

Ars Anatomica collection at University of Edinburgh image service (includes Vesalius's ''De Humanis Corporis Fabrica'')

a virtual copy of Vesalius's ''De Humanis Corporis Fabrica''. From the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

De humani corporis fabrica. Epitome

coloured and complete with manekin at

Cambridge Digital Library

The Cambridge Digital Library is a project operated by the Cambridge University Library designed to make items from the unique and distinctive collections of Cambridge University Library available online. The project was initially funded by a dona ...

* Texts digitized by the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé

The Interuniversity Health Library (French: ''Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de Santé'') is an inter-university medical library part of the network of 20 libraries of the Paris Cité University, in Paris, France. It is the heir to the libra ...

; see its digital librarMedic@

Vesalius four centuries later

by John F. Fulton. Logan Clendening lecture on the history and philosophy of medicine, University of Kansas, 1950. Full-text PDF. * Andreas Vesalius

''VESALIUS project''

. Information about the new DVD "De Humani Corporis Fabrica" produced by Health Science Library of the St. Anna Hospital in Ferrara – Italy.

Vesalius College in Brussels

TV report on 500th birthday Vesalius by tvbrussel

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem''

(1543) – full digital facsimile at

Linda Hall Library

The Linda Hall Library is a privately endowed American library of science, engineering and technology located in Kansas City, Missouri, on the grounds of a urban arboretum. It claims to be the "largest independently funded public library of sc ...

Vesalius at 500

– digital exhibition from the

University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou or MU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri, United States. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus Univers ...

Libraries

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vesalius, Andreas

1514 births

1564 deaths

Physicians from the Habsburg Netherlands

16th-century writers in Latin

Anatomists

Old University of Leuven alumni

University of Paris alumni

Academic staff of the University of Padua

16th-century scientists