Ancient science on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of science in early cultures covers protoscience in

From their beginnings in Sumer (now

From their beginnings in Sumer (now

mdash;but an abstract formulation of the Pythagorean theorem this was not.

Nevertheless, it applies the following components: examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, to the treatment of disease,

/sup> which display strong parallels to the basic

In

In  The level of achievement in Hellenistic

The level of achievement in Hellenistic

For example, he accurately describes the

For example, he accurately describes the

Excavations at

Excavations at

The first recorded observations of

The first recorded observations of

On July 4, 1054, Chinese astronomers observed a ''guest star'', a supernova, the remnant of which is now called the

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astr/hd_astr.htm .

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Science In Early Cultures

Early cultures

History of science and technology by region

ancient history

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history co ...

to Islamic Science. In these times, advice and knowledge was passed from generation to generation in an oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

. The development of writing

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically Epigraphy, inscribed, Printing press, mechanically transferred, or Word processor, digitally represented Symbols (semiot ...

enabled knowledge to be stored and communicated across generations with much greater fidelity. Combined with the development of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peop ...

, which allowed for a surplus of food, it became possible for early civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

C ...

s to develop and spend more of their time devoted to tasks other than survival, such as the search for knowledge for knowledge's sake.

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia

From their beginnings in Sumer (now

From their beginnings in Sumer (now Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

) around 3500 BC, the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

n peoples began to attempt to record some observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. Th ...

s of the world with extremely thorough numerical data

Level of measurement or scale of measure is a classification that describes the nature of information within the values assigned to variables. Psychologist Stanley Smith Stevens developed the best-known classification with four levels, or scal ...

. A concrete instance of Pythagoras' law was recorded as early as the 18th century BC—the Mesopotamian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedg ...

tablet Plimpton 322

Plimpton 322 is a Babylonian clay tablet, notable as containing an example of Babylonian mathematics. It has number 322 in the G.A. Plimpton Collection at Columbia University. This tablet, believed to have been written about 1800 BC, has a tab ...

records a number of Pythagorean triplets (3,4,5) (5,12,13) ..., dated to approx. 1800 BC, over a millennium before Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politic ...

mdash;but an abstract formulation of the Pythagorean theorem this was not.

Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

is a science that lends itself to the recording and study of observations: the rigorous notings of the motions of the star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night, but their immense distances from Earth make ...

s, planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a ...

s, and the moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

are left on thousands of clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a styl ...

s created by scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

s. Even today, astronomical periods identified by Mesopotamian scientists are still widely used in Western calendars: the solar year

A tropical year or solar year (or tropical period) is the time that the Sun takes to return to the same position in the sky of a celestial body of the Solar System such as the Earth, completing a full cycle of seasons; for example, the time ...

, the lunar month

In lunar calendars, a lunar month is the time between two successive syzygies of the same type: new moons or full moons. The precise definition varies, especially for the beginning of the month.

Variations

In Shona, Middle Eastern, and Europ ...

, the seven-day week

A week is a unit of time equal to seven days. It is the standard time period used for short cycles of days in most parts of the world. The days are often used to indicate common work days and rest days, as well as days of worship. Weeks are ofte ...

. Using these data they developed arithmetical methods to compute the changing length of daylight in the course of the year and to predict the appearances and disappearances of the Moon and planets and eclipses of the Sun and Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

. Only a few astronomers' names are known, such as that of Kidinnu

Kidinnu (also ''Kidunnu''; possibly fl. 4th century BC; possibly died 14 August 330 BC) was a Chaldean astronomer and mathematician. Strabo of Amaseia called him Kidenas, Pliny the Elder Cidenas, and Vettius Valens Kidynas.

Some cuneiform ...

, a Chaldea

Chaldea () was a small country that existed between the late 10th or early 9th and mid-6th centuries BCE, after which the country and its people were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia. Semitic-speaking, it was ...

n astronomer and mathematician who was contemporary with the Greek astronomers. Kiddinu's value for the solar year is in use for today's calendars. Astronomy and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

were considered to be the same thing, as evidenced by the practice of this science in Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

by priests. Indeed, rather than following the modern trend towards rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reasons. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an abil ...

science, moving away from superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs an ...

and belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to take ...

, the Mesopotamian astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

conversely became more astrology-based later in the civilisation - studying the stars in terms of horoscope

A horoscope (or other commonly used names for the horoscope in English include natal chart, astrological chart, astro-chart, celestial map, sky-map, star-chart, cosmogram, vitasphere, radical chart, radix, chart wheel or simply chart) is an as ...

s and omen

An omen (also called ''portent'') is a phenomenon that is believed to foretell the future, often signifying the advent of change. It was commonly believed in ancient times, and still believed by some today, that omens bring divine messages fr ...

s, which might explain the popularity of the clay tablets. Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

was to use this data to calculate the precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

's axis. Fifteen hundred years after Kiddinu, Al-Batani, born in what is now Turkey, would use the collected data and improve Hipparchus' value for the precession of the Earth's axis

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show axial parallelism. In particu ...

. Al-Batani's value, 54.5 arc-seconds per year, compares well to the current value of 49.8 arc-seconds per year (26,000 years for Earth's axis to round the circle of nutation

Nutation () is a rocking, swaying, or nodding motion in the axis of rotation of a largely axially symmetric object, such as a gyroscope, planet, or bullet in flight, or as an intended behaviour of a mechanism. In an appropriate reference fra ...

).

Babylonian astronomy

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

Babylonian astronomy seemed to have focused on a select group of stars and constellations known as Ziqpu stars. These constellations ...

was "the first and highly successful attempt at giving a refined mathematical description of astronomical phenomena." According to the historian A. Aaboe,

Egypt

Significant advances in ancient Egypt included astronomy, mathematics and medicine. Theirgeometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

was a necessary outgrowth of surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

to preserve the layout and ownership of farmland, which was flooded annually by the Nile river

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ri ...

. The 3-4-5 right triangle

A right triangle (American English) or right-angled triangle ( British), or more formally an orthogonal triangle, formerly called a rectangled triangle ( grc, ὀρθόσγωνία, lit=upright angle), is a triangle in which one angle is a right ...

and other rules of thumb served to represent rectilinear structures including their post and lintel

In architecture, post and lintel (also called prop and lintel or a trabeated system) is a building system where strong horizontal elements are held up by strong vertical elements with large spaces between them. This is usually used to hold up ...

architecture. Egypt was also a centre of alchemical

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wor ...

research for much of the western world.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

, a phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

writing system

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable for ...

, have served as the basis for the Egyptian Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet (more specifically, an abjad) known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

The Phoenician a ...

from which the later Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

, Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

, and Cyrillic alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a s ...

s were derived. The city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

retained preeminence with its library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

, which was damaged by fire when it fell under Roman rule,Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, ''Life of Caesar'' 49.3. being completely destroyed before 642. With it a huge amount of antique literature and knowledge was lost.

The Edwin Smith papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical text, named after Edwin Smith who bought it in 1862, and the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma. From a cited quotation in another text, it may have been known to ancient surgeons as ...

is one of the first medical documents still extant, and perhaps the earliest document that attempts to describe and analyse the brain: it might be seen as the very beginnings of modern neuroscience

Neuroscience is the science, scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions and disorders. It is a Multidisciplinary approach, multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, an ...

. However, while Egyptian medicine had some effective practices, it was not without its ineffective and sometimes harmful practices. Medical historians believe that ancient Egyptian pharmacology, for example, was largely ineffective.

Microsoft Word - Proceedings-2001.docNevertheless, it applies the following components: examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, to the treatment of disease,

/sup> which display strong parallels to the basic

empirical method

Empirical research is research using empirical evidence. It is also a way of gaining knowledge by means of direct and indirect observation or experience. Empiricism values some research more than other kinds. Empirical evidence (the record of on ...

of science and according to G. E. R. Lloyd played a significant role in the development of this methodology. The Ebers papyrus (c. 1550 BC) also contains evidence of traditional empiricism.

According to a paper published by Michael D. Parkins, 72% of 260 medical prescriptions in the Hearst Papyrus had no curative elements. According to Michael D. Parkins, sewage pharmacology first began in ancient Egypt and was continued through the Middle Ages. Practices such as applying cow dung to wounds, ear piercing and tattooing, and chronic ear infections were important factors in developing tetanus. Frank J. Snoek wrote that Egyptian medicine used fly specks, lizard blood, swine teeth, and other such remedies which he believes could have been harmful.

Persia

In theSassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Name ...

period (226 to 652 AD), great attention was given to mathematics and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

. The Academy of Gundishapur is a prominent example in this regard. Astronomical tables—such as the Shahryar Tables—date to this period, and Sassanid observatories were later imitated by Muslim astronomers and astrologers

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

of the Islamic period

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main ...

.

In the mid-Sassanid era, an influx of knowledge came to Persia from the West in the form of views and traditions of Greece which, following the spread of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, accompanied Syriac (the official language of Christians as well as the Iranian Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

s). The Christian schools in Iran have produced great scientists such as Nersi, Farhad, and Marabai. Also, a book was left by Paulus Persa, head of the Iranian Department of Logic and Philosophy of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, written in Syriac and dictated to Sassanid King Anushiravan.

A fortunate incident for pre-Islamic Iranian science during the Sassanid period was the arrival of eight great scholars from the Hellenistic civilization

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, who sought refuge in Persia from persecution by the Roman Emperor Justinian. These men were the followers of the Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some i ...

school. King Anushiravan had many discussions with these men and especially with the man named Priscianus. A summary of these discussions was compiled in a book entitled ''Solution to the Problems of Khosrow, the King of Persia'', which is now in the Saint Germain Library in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

. These discussions touched on several subjects, such as philosophy, physiology, metabolisms, and natural science as astronomy. After the establishment of Umayyad and Abbasid states, many Iranian scholars were sent to the capitals of these Islamic dynasties.

In the Early Middle Ages, Persia became a stronghold of Islamic science

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate an ...

.

Greco-Roman world

Scientific thought inClassical Antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

becomes tangible from the 6th century BC in pre-Socratic philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

(Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard ...

, Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politic ...

). In c. 385 BC, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

founded the Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosop ...

. With Plato's student Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

begins the "scientific revolution" of the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

culminating in the 3rd to 2nd centuries with scholars such as Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

, Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

, Aristarchus of Samos, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

and Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scienti ...

.

In

In Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

, the inquiry into the workings of the universe took place both in investigations aimed at such practical goals as establishing a reliable calendar or determining how to cure a variety of illnesses and in those abstract investigations known as natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

. The ancient people who are considered the first ''scientists

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophi ...

'' may have thought of themselves as ''natural philosophers'', as practitioners of a skilled profession (for example, physicians), or as followers of a religious tradition (for example, temple healers).

The earliest Greek philosophers, known as the pre-Socratics, provided competing answers to the question found in the myths of their neighbours: "How did the ordered cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

in which we live come to be?" The pre-Socratic philosopher Thales, dubbed the "father of science", was the first to postulate non-supernatural explanations for natural phenomena such as lightning and earthquakes. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politic ...

of Samos founded the Pythagorean school

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

, which investigated mathematics for its own sake, and was the first to postulate that the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

is spherical in shape. Subsequently, Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

produced the first systematic discussions of natural philosophy, which did much to shape later investigations of nature. Their development of deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is deductively valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, i.e. if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false ...

was of particular importance and usefulness to later scientific inquiry.

The important legacy of this period included substantial advances in factual knowledge, especially in anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

, zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

, geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, a ...

, mathematics and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

; an awareness of the importance of certain scientific problems, especially those related to the problem of change and its causes; and a recognition of the methodological importance of applying mathematics to natural phenomena and of undertaking empirical research. In the Hellenistic age

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

scholars frequently employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought: the application of mathematics and deliberate empirical research, in their scientific investigations. Thus, clear unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Hellenistic philosophers

Hellenistic philosophy is a time-frame for Western philosophy and Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period. It is purely external and encompasses disparate intellectual content. There is no single philosophical school or cu ...

, to medieval Muslim philosophers

Muslim philosophers both profess Islam and engage in a style of philosophy situated within the structure of the Arabic language and Islam, though not necessarily concerned with religious issues. The sayings of the companions of Muhammad contained ...

and scientists

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophi ...

, to the Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

an Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

and Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, to the secular science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

s of the modern day.

Neither reason nor inquiry began with the Ancient Greeks, but the Socratic method

The Socratic method (also known as method of Elenchus, elenctic method, or Socratic debate) is a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw ...

did, along with the idea of Forms, great advances in geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

, and the natural sciences. Benjamin Farrington, former Professor of Classics at Swansea University

, former_names=University College of Swansea, University of Wales Swansea

, motto= cy, Gweddw crefft heb ei dawn

, mottoeng="Technical skill is bereft without culture"

, established=1920 – University College of Swansea 1996 – University of Wa ...

wrote:

:"Men were weighing for thousands of years before Archimedes worked out the laws of equilibrium; they must have had practical and intuitional knowledge of the principles involved. What Archimedes did was to sort out the theoretical implications of this practical knowledge and present the resulting body of knowledge as a logically coherent system."

and again:

:"With astonishment we find ourselves on the threshold of modern science. Nor should it be supposed that by some trick of translation the extracts have been given an air of modernity. Far from it. The vocabulary of these writings and their style are the source from which our own vocabulary and style have been derived."

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific method, scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad rang ...

is impressively shown by the Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( ) is an Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery, described as the oldest example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-y ...

(150-100 BC). The astronomer Aristarchus of Samos was the first known person to propose a heliocentric model of the solar system, while the geographer Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

accurately calculated the circumference of the Earth. Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

(c. 190 – c. 120 BC) produced the first systematic star catalog

A star catalogue is an astronomical catalogue that lists stars. In astronomy, many stars are referred to simply by catalogue numbers. There are a great many different star catalogues which have been produced for different purposes over the years ...

. In medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, Herophilos

Herophilos (; grc-gre, Ἡρόφιλος; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first sci ...

(335 - 280 BC) was the first to base his conclusions on dissection of the human body and to describe the nervous system

In Biology, biology, the nervous system is the Complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its Behavior, actions and Sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its ...

. Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

(c. 460 BC – c. 370 BC) and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions. Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

(129 – c. 200 AD) performed many audacious operations—including brain and eye surgeries

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

— that were not tried again for almost two millennia. The mathematician Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

laid down the foundations of mathematical rigour

Rigour (British English) or rigor (American English; see spelling differences) describes a condition of stiffness or strictness. These constraints may be environmentally imposed, such as "the rigours of famine"; logically imposed, such as m ...

and introduced the concepts of definition, axiom, theorem and proof still in use today in his ''Elements'', considered the most influential textbook ever written. Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scienti ...

, considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, is credited with using the method of exhaustion

The method of exhaustion (; ) is a method of finding the area of a shape by inscribing inside it a sequence of polygons whose areas converge to the area of the containing shape. If the sequence is correctly constructed, the difference in area b ...

to calculate the area

Area is the quantity that expresses the extent of a region on the plane or on a curved surface. The area of a plane region or ''plane area'' refers to the area of a shape or planar lamina, while ''surface area'' refers to the area of an open su ...

under the arc of a parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descri ...

with the summation of an infinite series, and gave a remarkably accurate approximation of pi. He is also known in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

for laying the foundations of hydrostatics

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body "fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imme ...

and the explanation of the principle of the lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

.

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

wrote some of the earliest descriptions of plants and animals, establishing the first taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

and looking at minerals in terms of their properties such as hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion (mechanical), abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardn ...

. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

produced what is one of the largest encyclopedia

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

s of the natural world in 77 AD, and must be regarded as the rightful successor to Theophrastus.

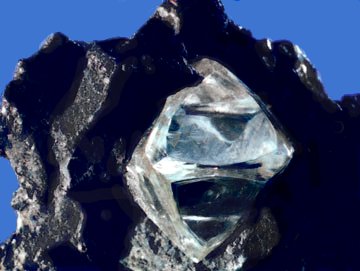

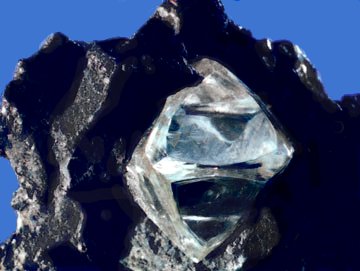

For example, he accurately describes the

For example, he accurately describes the octahedral

In geometry, an octahedron (plural: octahedra, octahedrons) is a polyhedron with eight faces. The term is most commonly used to refer to the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at ea ...

shape of the diamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, ...

, and proceeds to mention that diamond dust is used by engravers to cut and polish other gems owing to its great hardness. His recognition of the importance of crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macr ...

shape is a precursor to modern crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics (condensed matter physics). The wo ...

, while mention of numerous other minerals presages mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

. He also recognises that other minerals have characteristic crystal shapes, but in one example, confuses the crystal habit

In mineralogy, crystal habit is the characteristic external shape of an individual crystal or crystal group. The habit of a crystal is dependent on its crystallographic form and growth conditions, which generally creates irregularities due to l ...

with the work of lapidaries. He was also the first to recognise that amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

was a fossilized resin from pine trees because he had seen samples with trapped insects within them.

India

Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

, Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900 ...

(IVC) have uncovered evidence of the use of "practical mathematics". The people of the IVC manufactured bricks whose dimensions were in the proportion 4:2:1, considered favourable for the stability of a brick structure. They used a standardised system of weights based on the ratios: 1/20, 1/10, 1/5, 1/2, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500, with the unit weight equaling approximately 28 grammes (and approximately equal to the English ounce or Greek uncia). They mass-produced weights in regular geometrical

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

shapes, which included hexahedra

A hexahedron (plural: hexahedra or hexahedrons) or sexahedron (plural: sexahedra or sexahedrons) is any polyhedron with six faces. A cube, for example, is a regular hexahedron with all its faces square, and three squares around each vertex.

The ...

, barrel

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids, ...

s, cones, and cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infi ...

s, thereby demonstrating knowledge of basic geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

.

The inhabitants of Indus civilisation also tried to standardise measurement of length to a high degree of accuracy. They designed a ruler—the ''Mohenjo-daro ruler''—whose unit of length (approximately 1.32 inches or 3.4 centimetres) was divided into ten equal parts. Bricks manufactured in ancient Mohenjo-daro often had dimensions that were integral multiples of this unit of length.

Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh (; ur, ) is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated ) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta ...

, a Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

IVC site, provides the earliest known evidence for ''in vivo'' drilling of human teeth, with recovered samples dated to 7000-5500 BCE.

Early astronomy in India—like in other cultures— was intertwined with religion.Sarma (2008), ''Astronomy in India'' The first textual mention of astronomical concepts comes from the Veda

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

s—religious literature of India. According to Sarma (2008): "One finds in the Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only one ...

intelligent speculations about the genesis of the universe from nonexistence, the configuration of the universe, the spherical self-supporting earth, and the year of 360 days divided into 12 equal parts of 30 days each with a periodical intercalary month."

Classical Indian astronomy

Astronomy has long history in Indian subcontinent stretching from pre-historic to modern times. Some of the earliest roots of Indian astronomy can be dated to the period of Indus Valley civilisation or earlier. Astronomy later developed as a di ...

documented in literature spans the Maurya (Vedanga Jyotisha

Vedanga Jyotisha (), or Jyotishavedanga (), is one of earliest known Indian texts on astrology (''Jyotisha''). The extant text is dated to the final centuries BCE, but it may be based on a tradition reaching back to about 700-600 BCE.

The text ...

, c. 5th century BCE) to the Vijaynagara(South India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and T ...

) (such as the 16th century Kerala school) periods. The first named authors writing treatises on astronomy emerge from the 5th century, the date when the classical period of Indian astronomy can be said to begin. Besides the theories of Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (whi ...

in the ''Aryabhatiya

''Aryabhatiya'' ( IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the ''magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philosopher of astronomy Roger Billard estimates that ...

'' and the lost ''Arya-siddhānta'', we find the '' Pancha-Siddhāntika'' of Varahamihira. The astronomy and the astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

of ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by ...

(Jyotisha

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit ', from ' “light, heavenly body" and ''ish'' - from Isvara or God) is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. It is on ...

) is based upon sidereal calculations, although a tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

system was also used in a few cases.

Alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world ...

(Rasaśāstra in Sanskrit)was popular in India. It was the Indian alchemist and philosopher Kanada who introduced the concept of 'anu' which he defined as the matter which cannot be subdivided. This is analogous to the concept of atom in modern science.

Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Lingu ...

(along with phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

, morphology, etc.) first arose among Indian grammarians studying the Sanskrit language

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the lat ...

. Aacharya Hemachandrasuri wrote grammars of Sanskrit and Prakrit, poetry, prosody, lexicons, texts on science and logic and many branches of Indian philosophy. The ''Siddha-Hema-Śabdanuśāśana'' includes six Prakrit languages: the "standard" Prakrit

The Prakrits (; sa, prākṛta; psu, 𑀧𑀸𑀉𑀤, ; pka, ) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usu ...

(virtually Maharashtri Prakrit

Maharashtri or Maharashtri Prakrit ('), is a Prakrit language of ancient as well as medieval India and the ancestor of Marathi and Konkani.

Maharashtri Prakrit was commonly spoken until 875 CEV.Rajwade, ''Maharashtrache prachin rajyakarte''

), Shauraseni, Magahi

The Magahi language (), also known as Magadhi (), is a language spoken in Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal states of eastern India, and in the Terai of Nepal. Magadhi Prakrit was the ancestor of Magahi, from which the latter's name derives. ...

, Paiśācī, the otherwise-unattested Cūlikāpaiśācī and Apabhraṃśa (virtually Gurjar Apabhraṃśa, prevalent in the area of Gujarat and Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern s ...

at that time and the precursor of Gujarati language

Gujarati (; gu, ગુજરાતી, Gujarātī, translit-std=ISO, label=Gujarati script, ) is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat and spoken predominantly by the Gujarati people. Gujarati is descended from Old Guj ...

). He gave a detailed grammar of Apabhraṃśa and also illustrated it with the folk literature of the time for better understanding. It is the only known Apabhraṃśa grammar. The Sanskrit grammar

The grammar of the Sanskrit language has a complex verbal system, rich nominal declension, and extensive use of compound nouns. It was studied and codified by Sanskrit grammarians from the later Vedic period (roughly 8th century BCE), culminat ...

of Pāṇini

, era = ;;6th–5th century BCE

, region = Indian philosophy

, main_interests = Grammar, linguistics

, notable_works = ' ( Classical Sanskrit)

, influenced=

, notable_ideas= Descriptive linguistics

(Devanag ...

(c. 520 – 460 BCE) contains a particularly detailed description of Sanskrit morphology, phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

and roots, evincing a high level of linguistic insight and analysis.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population repor ...

medicine traces its origins to the Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

, Atharvaveda in particular, and is connected to Hindu religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural ...

. The ''Sushruta Samhita

The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (सुश्रुतसंहिता, IAST: ''Suśrutasaṃhitā'', literally "Suśruta's Compendium") is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, and one of the most important such treatises on this subj ...

'' of Sushruta

Sushruta, or ''Suśruta'' (Sanskrit: सुश्रुत, IAST: , ) was an ancient Indian physician. The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (''Sushruta's Compendium''), a treatise ascribed to him, is one of the most important surviving ancient treatises on ...

appeared during the 1st millennium BC.Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007) Ayurvedic practice was flourishing during the time of Buddha (around 520 BC), and in this period the Ayurvedic practitioners were commonly using Mercuric-sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

combination based medicines. An important Ayurvedic practitioner of this period was Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna . 150 – c. 250 CE (disputed)was an Indian Mahāyāna Buddhist thinker, scholar-saint and philosopher. He is widely considered one of the most important Buddhist philosophers.Garfield, Jay L. (1995), ''The Fundamental Wisdom of ...

, accompanied by Surananda, Nagbodhi, Yashodhana, Nityanatha, Govinda

Govinda (), also rendered Govind and Gobind, is an epithet of Vishnu which is also used for his avatars such as Krishna. The name appears as the 187th and the 539th name of Vishnu in '' Vishnu Sahasranama''. The name is also popularly addresse ...

, Anantdev, Vagbhatta etc.

During the regime of Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

(375-415 AD), Ayurveda was part of mainstream Indian medical techniques, and continued to be so until the Colonial period.

The main authors of classical Indian mathematics

Indian mathematics emerged in the Indian subcontinent from 1200 BCE until the end of the 18th century. In the classical period of Indian mathematics (400 CE to 1200 CE), important contributions were made by scholars like Aryabhata, Brahmagupt ...

(400 CE to 1200 CE) were scholars like Mahaviracharya, Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (whi ...

, Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

, and Bhaskara II. Indian mathematicians made early contributions to the study of the decimal number system

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers of the Hindu–Arabic nume ...

, zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. In place-value notation such as the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, 0 also serves as a placeholder numerical digit, which works by multiplying digits to the left of 0 by the radix, usu ...

, negative numbers

In mathematics, a negative number represents an opposite. In the real number system, a negative number is a number that is less than zero. Negative numbers are often used to represent the magnitude of a loss or deficiency. A debt that is owed ma ...

, arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th c ...

, and algebra

Algebra () is one of the areas of mathematics, broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathem ...

. In addition, trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

, having evolved in the Hellenistic world and having been introduced into ancient India through the translation of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

works, was further advanced in India, and, in particular, the modern definitions of sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side that is opp ...

and cosine were developed there. These mathematical concepts were transmitted to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, China, and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

and led to further developments that now form the foundations of many areas of mathematics.

China and the Far East

The first recorded observations of

The first recorded observations of solar eclipses

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six mon ...

and supernovae were made in China.Ancient Chinese AstronomyOn July 4, 1054, Chinese astronomers observed a ''guest star'', a supernova, the remnant of which is now called the

Crab Nebula

The Crab Nebula (catalogue designations Messier object, M1, New General Catalogue, NGC 1952, Taurus (constellation), Taurus A) is a supernova remnant and pulsar wind nebula in the constellation of Taurus (constellation), Taurus. The common name ...

. Korean contributions include similar records of meteor showers and eclipses, particularly from 1500-1750 in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty

The ''Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty'' (also known as the ''Annals of the Joseon Dynasty'' or the ''True Record of the Joseon Dynasty''; ko, 조선왕조실록 and ) are the annual records of Joseon, the last royal house to rule K ...

. Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medicine, alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. It has been described as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logica ...

, acupuncture

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scient ...

and herbal medicine were also practised, with similar medicine practised in Korea.

Among the earliest inventions were the abacus

The abacus (''plural'' abaci or abacuses), also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool which has been used since ancient times. It was used in the ancient Near East, Europe, China, and Russia, centuries before the adoption of the H ...

, the public toilet, and the "shadow clock".''Inventions'' (Pocket Guides). Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, ini ...

noted the " Four Great Inventions" of China as among some of the most important technological advances; these were the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

, gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter) ...

, papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

, and printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

, which were later known in Europe by the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. The Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

(AD 618 - 906) in particular was a time of great innovation. A good deal of exchange occurred between Western and Chinese discoveries up to the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

.

However, Needham and most scholars recognised that cultural factors prevented these Chinese achievements from developing into what might be considered "modern science".

It was the religious and philosophical framework of the Chinese intellectuals which made them unable to believe in the ideas of laws of nature:

Islamic Science

There are many time periods involved within the history of science which is still continued to this day. One major tine period is between the 7th and 16th century which marks the time period of the embarking of Islamic science under the development of islamic civilizations. The are many reason why science flourished in this time period within the region. The most important reason being was that islamic religion and the islamic government greatly supported the ones researching and further expanding their knowledge on science, The researchers were also greatly respected by the people. Within the people researching there wasIbn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

, out of the many things he did including writing The Canon of Medicine; he established free hospitals and developed many great treatments unknown to man. Another person to receive recognition was Al-Riza who wrote Treatise on Small-poxs and Measles, he created separate wings in hospitals for the mentally ill which was un-heard of. Besides these two men there are many other researches who expanded the knowledge of Science within the Islamic civilizations. When there is a rise there will always be a fall. The reign of knowledge pertaining to Science has mostly come to an end in the islamic civilizations. When religious leaders started to gain more political power within the community the more research done on scientific topics started to come to a halt.

Islamic Medicine

During this time period many attributions were made to the medical knowledge known to man and this completely changed the face of medicine before this time. Before this time there was some knowledge that the islamic researches and people had access to like Hippocrates and Galen being the main two, with this knowledge they could further expand the topics of Medicine. Like said before one of the two main physicians within this time period was Ibn-Sina what wrote "The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

" was a very important figure within the expansion of knowledge. The Canon of Medicine, which is still the most popular and used medical textbooks in the world. This book is divided into fiver chapters; Chapter one : is a basic knowledge over medical principles as well an overview of anatomy and therapeutic procedures, Chapter Two: Is an overview of medical substances and their general properties, Chapter three : This chapter contains diagnosis and treatments of diseases known to a specific body part or Organ, Chapter four: covers conditions or diseases not specific to one part of the body, and finally chapter five: is over Compound remedies and their formulas.

The second main researcher of the reign in expanding knowledge during the Islamic time period was Al-Riza, he is sometimes known in the Medieval period as the greatest physician of his time. Al-Riza created over two-hundred works and over half of those works are basically over medical knowledge. The most important work that Riza ever did was ''Kitab al-Hawi fi al-tibb'' or commonly known as The Comprehensive book of Medicine. This is considered one of his most important works because it was created by his personal medical notes collected throughout the years over everything he has read and observations of medical experience coming straight from his own eyes. The ''Kitab al-Hawi fi al-tibb'' is a collaboration of 23 volumes all pertaining different information, Each value goes into detail over specific diseases and parts of the body.

There are many other important figures within this time period that further expanded the knowledge of medicine but Ibn-Sina and Al-Riza are acknowledged to be the most important figures of this time.

Islamic Astronomy