Ancient Cyprus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ancient history of Cyprus shows a precocious sophistication in the  Alexander's conquests only served to accelerate an already clear drift towards Hellenisation in Cyprus. His premature death in 323 BC led to a period of turmoil as

Alexander's conquests only served to accelerate an already clear drift towards Hellenisation in Cyprus. His premature death in 323 BC led to a period of turmoil as

Cyprus gained independence after 627 BC following the death of Ashurbanipal, the last great Assyrian king. Cemeteries from this period are chiefly rock-cut tombs. They have been found, among other locations, at

Cyprus gained independence after 627 BC following the death of Ashurbanipal, the last great Assyrian king. Cemeteries from this period are chiefly rock-cut tombs. They have been found, among other locations, at

In 525 BCE, the Persian

In 525 BCE, the Persian

Ancient History of Cyprus, by the Cypriot government

.

History of Cyprus, Lonely Planet Travel Information

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ancient History of Cyprus Phoenician colonies

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

era visible in settlements such as at Choirokoitia dating from the 9th millennium BC, and at Kalavassos from about 7500 BC.

Periods of Cyprus's ancient history from 1050 BC have been named according to styles of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

as follows:

* Cypro-Geometric I: 1050–950 BC

* Cypro-Geometric II: 950–850 BC

* Cypro-Geometric III: 850–700 BC

* Cypro-Archaic I: 700–600 BC

* Cypro-Archaic II: 600–475 BC

* Cypro-Classical I: 475–400 BC

* Cypro-Classical II: 400–323 BC

The documented history of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

begins in the 8th century BC. The town of Kition, now Larnaka, recorded part of the ancient history of Cyprus on a stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

that commemorated a victory by Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

(722–705 BC) of Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

there in 709 BC. Assyrian domination of Cyprus (known as ''Iatnanna'' by the Assyrians) appears to have begun earlier than this, during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (744–727 BC), and ended with the fall of the Neo Assyrian Empire in 609 BC, whereupon the city-kingdoms of Cyprus gained independence once more. Following a brief period of Egyptian domination in the sixth century BC, Cyprus fell under Persian rule. The Persians did not interfere in the internal affairs of Cyprus, leaving the city-kingdoms to continue striking their own coins and waging war amongst one another, until the late-fourth century BC saw the overthrow of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

.

Alexander's conquests only served to accelerate an already clear drift towards Hellenisation in Cyprus. His premature death in 323 BC led to a period of turmoil as

Alexander's conquests only served to accelerate an already clear drift towards Hellenisation in Cyprus. His premature death in 323 BC led to a period of turmoil as Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

and Demetrius I of Macedon

Demetrius I Poliorcetes (; , , ; ) was a Macedonian Greek nobleman and military leader who became king of Asia between 306 and 301 BC, and king of Macedon between 294 and 288 BC. A member of the Antigonid dynasty, he was the son of its founder, ...

fought together for supremacy in that region, but by 294 BC, the Ptolemaic kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

had regained control and Cyprus remained under Ptolemaic rule until 58 BC, when it became a Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

. During this period, Phoenician and native Cypriot traits disappeared, together with the old Cypriot syllabic script, and Cyprus became thoroughly Hellenised. Cyprus figures prominently in the early history of Christianity, being the first province of Rome to be ruled by a Christian governor, in the first century, and providing a backdrop for events in the New Testament

Early history

Mycenaean settlement

The Ancient Greek historianHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

(5th century BC) claims that the city of Kourion

Kourion (; ) was an important ancient Greek city-state on the southwestern coast of the island of Cyprus. In the twelfth century BCE, after the Mycenaean Greece#Collapse or Postpalatial Bronze Age (c. 1200–1050 BC), collapse of the Mycenaean p ...

, near present-day Limassol

Limassol, also known as Lemesos, is a city on the southern coast of Cyprus and capital of the Limassol district. Limassol is the second-largest urban area in Cyprus after Nicosia, with an urban population of 195,139 and a district population o ...

, was founded by Achaean settlers from Argos. This is further supported by the discovery of a Late Bronze Age settlement lying several kilometres from the site of the remains of the Hellenic city of Kourion, whose pottery and architecture indicate that Mycenaean settlers did indeed arrive and augment an existing population in this part of Cyprus in the twelfth century BC.Christou, Demos, 1986. ''Kourion: A Complete Guide to Its Monuments and Local Museum''. Filokipros Publishing Co. Ltd., Nicosia. Introduction, p 7. The kingdom of Kourion in Cyprus is recorded on an inscription dating to the period of the Pharaoh Ramses III (1186–1155 BC) in Egypt.

Phoenician presence

ThePhoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns who came from Tyre, colonized some cities of Cyprus, such as Idalium, Kition, Marion, Salamis and Tamassos

Tamassos (Greek: Ταμασσός) or Tamasos (Greek: Τἀμασος) – names Latinized as Tamassus or Tamasus – was a city-kingdom in ancient Cyprus, one of the ten kingdoms of Cyprus. It was situated in the great central plain of the i ...

and founded the city of Lapathus.

Egyptian and Hittite rule

PharaohThutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, (1479–1425 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He is regarded as one of the greatest warriors, military commanders, and milita ...

of Egypt subdued Cyprus in 1500 BC and forced its inhabitants to pay tribute, which continued until Egyptian rule was replaced by the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

(who called Cyprus Alashiya in their language) in the 13th century BC. After the invasion of The Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

(approx. 1200 BC), the Greeks settled on the island (ca. 1100 BC), acting decisively in the formation of their cultural identity. The Hebrews

The Hebrews (; ) were an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic-speaking people. Historians mostly consider the Hebrews as synonymous with the Israelites, with the term "Hebrew" denoting an Israelite from the nomadic era, which pre ...

called Cyprus The Kittim Island.

Assyrian conquest

An early written source of Cypriot history mentions the nation underAssyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

n rule as stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

found in 1845 in the city formerly named Kition, near present-day Larnaka, commemorates the victory of King Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

(721–05 BC) in 709 BC over seven kings in the land of Ia', in the district of Iadnana or Atnana. The land of Ia' is assumed to be the Assyrian name for Cyprus, and some scholars suggest that the latter may mean 'the islands of the Danaans', or Greece. There are other inscriptions referring to the land of Ia' in Sargon's palace at Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

.

The ten kingdoms listed on the prism of Esarhaddon in 673–2 BC have been identified as Soloi, Salamis, Paphos, Kourion, Amathus and Kition on the coast, and Tamassos

Tamassos (Greek: Ταμασσός) or Tamasos (Greek: Τἀμασος) – names Latinized as Tamassus or Tamasus – was a city-kingdom in ancient Cyprus, one of the ten kingdoms of Cyprus. It was situated in the great central plain of the i ...

, Ledrai, Idalion and Chytroi in the interior of the island. Later inscriptions add Marion, Lapithos and Kerynia ( Kyrenia).

Independent city-kingdoms

Tamassos

Tamassos (Greek: Ταμασσός) or Tamasos (Greek: Τἀμασος) – names Latinized as Tamassus or Tamasus – was a city-kingdom in ancient Cyprus, one of the ten kingdoms of Cyprus. It was situated in the great central plain of the i ...

, Soloi, Patriki and Trachonas. The rock-cut 'Royal' tombs at Tamassos

Tamassos (Greek: Ταμασσός) or Tamasos (Greek: Τἀμασος) – names Latinized as Tamassus or Tamasus – was a city-kingdom in ancient Cyprus, one of the ten kingdoms of Cyprus. It was situated in the great central plain of the i ...

, built in about 600 BC, imitate wooden houses. The pillars show Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n influence. Some graves contain the remains of horses and chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

s.

The main deity of ancient Cyprus was the Great Goddess, the Assyro-Babylonian Ishtar

Inanna is the List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian goddess of war, love, and fertility. She is also associated with political power, divine law, sensuality, and procreation. Originally worshipped in Sumer, she was known by the Akk ...

, and Phoenician Astarte

Astarte (; , ) is the Greek language, Hellenized form of the Religions of the ancient Near East, Ancient Near Eastern goddess ʿAṯtart. ʿAṯtart was the Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic equivalent of the East Semitic language ...

, later known by the Greek name Aphrodite

Aphrodite (, ) is an Greek mythology, ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, procreation, and as her syncretism, syncretised Roman counterpart , desire, Sexual intercourse, sex, fertility, prosperity, and ...

. She was called "the lady of Kypros" by Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

. Paphian inscriptions call her "the Queen". Pictures of Aphrodite appear on the coins of Salamis as well, demonstrating that her cult had a larger regional influence. In addition, the King of Paphos was the High Priest of Aphrodite, and a great pilgrim temple of her, the Sanctuary of Aphrodite Paphia, was situated in Paphia.

Other Gods venerated include the Phoenician Anat, Baal

Baal (), or Baʻal, was a title and honorific meaning 'owner' or 'lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The ...

, Eshmun, Reshef, Mikal and Melkart

Melqart () was the tutelary god of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre and a major deity in the Phoenician and Punic pantheons. He may have been central to the founding-myths of various Phoenician colonies throughout the Mediterranean, as well ...

and the Egyptian Hathor

Hathor (, , , Meroitic language, Meroitic: ') was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god R ...

, Thoth

Thoth (from , borrowed from , , the reflex of " eis like the ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an African sacred ibis, ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine count ...

, Bes and Ptah, as attested by amulets. Animal sacrifices are attested to on terracotta-votives. The sanctuary of Ayia Irini contained over 2,000 figurines.

Egyptian period

In 570 BCE, Cyprus was conquered byEgypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

under Amasis II

Amasis II ( ; ''ḤMS'') or Ahmose II was a pharaoh (reigned 570526 BCE) of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the successor of Apries at Sais, Egypt, Sais. He was the last great ruler of Ancient Egypt, Egypt before the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

. This brief period of Egyptian domination left its influence mainly in the arts, especially sculpture, where the rigidity and the dress of the Egyptian style can be observed. Cypriot artists later discarded this Egyptian style in favour of Greek prototypes.

Statues in stone often show a mixture of Egyptian and Greek influence. In particular, ceramics recovered on Cyprus show influence from ancient Crete

The history of Crete goes back to the 7th millennium BC, preceding the ancient Minoan civilization by more than four millennia. The Minoan civilization was the first civilization in Europe.

During the Iron Age, Crete developed an Ancient Greece-i ...

. Men often wore Egyptian wigs and Assyrian-style beards. Armour and dress showed western Asiatic elements as well.

Persian period

In 525 BCE, the Persian

In 525 BCE, the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

conquered Cyprus. Under the Persians, the Kings of Cyprus retained their independence but had to pay tribute to their overlord. The city-kingdoms began to strike their own coins in the late-sixth century BCE, using the Persian weight system. Coins minted by the kings were required to have the overlord's portrait on them. King Evelthon of Salamis (560–25 BCE) was probably the first to cast silver or bronze coins in Cyprus; the coins were designed with a ram on the obverse and an ankh (Egyptian symbol of good luck) on the reverse.

Royal palaces have been excavated in Palaepaphos and in Vouni in the territory of Marion on the North coast. They closely follow Persian examples like Persepolis

Persepolis (; ; ) was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by the southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian cultural heritage sites and ...

. Vouni, on a hill overlooking Morphou Bay, was built around 520 BCE and destroyed in 380 BCE. It contained Royal audience chambers (liwan

Liwan (, , from Persian ) is a long narrow-fronted hall or vaulted portal in ancient and modern Levantine homes that is often open to the outside.Abercrombie, 1910, p. 266.Davey, 1993, p. 29. An Arabic loanword to English, it is ultimately der ...

), open courtyards, bathhouses and stores.

Towns in Cyprus during this period were fortified with mudbrick

Mudbrick or mud-brick, also known as unfired brick, is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of mud (containing loam, clay, sand and water) mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE.

From ...

walls on stone foundations and rectangular bastions. The houses were constructed of mud-bricks as well, whereas public buildings were faced with ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

. The Phoenician town of Carpasia, near Rizokarpasso (), had houses built of rubble masonry with square stone blocks forming the corners. Temples and sanctuaries were built mainly in a Phoenician style. Soloi had a small temple with a Greek plan.

A definite influence from Greece was responsible for the production of some very important sculptures. The archaic Greek art with its attractive smile on the face of the statue is found on many Cypriot pieces dating between 525–475 BCE; that is, the closing years of the Archaic period in Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in History of Greece, Greek history lasting from to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical Greece, Classical period. In the archaic period, the ...

. During the Persian rule, Ionian influence on the sculptures intensified; copies of Greek korai appear, as well as statues of men in Greek dress. Naked kouroi, however, although common in Greece, are extremely rare in Cyprus, while women (Korai) are always presented dressed with rich folds in their garments. The pottery in Cyprus retained its local influences, although some Greek pottery was imported.

The most important obligation of the kings of Cyprus to the Shah of Persia was the payment of tribute and the supply of armies and ships for his foreign campaigns. Thus, when Xerxes in 480 BC invaded Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Cyprus contributed 150 ships to the Persian military expedition.

Ionian revolt

Except for the royal city of Amathus, the Kingdoms of Cyprus took part in the Ionian Revolt in 499 BC. The revolt on Cyprus was led by Onesilos of Salamis, brother of the King of Salamis, whom he dethroned for not wanting to fight for independence. The Persians crushed the Cypriot armies and laid siege to the fortified towns in 498 BCE. Soloi surrendered after a five-month siege. Around 450 BCE, Kition annexed Idalion with Persian help. The importance of Kition increased again when it acquired the Tamassos copper-mines.Evagoras I of Salamis

Evagoras I of Salamis (435–374 BCE) dominated Cypriot politics for almost forty years until his death in 374 BCE. He had favoured Athens during the closing years of thePeloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

, elicited Persian support for the Athenians against Sparta and urged Greeks from the Aegean to settle in Cyprus, assisting the Athenians in so many ways that they honoured him by erecting his statue in the Stoa (portico) Basileios in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. At the beginning of the 4th century BC, he took control of the whole island of Cyprus and within a few years was attempting to gain independence from Persia with Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

help.

Following resistance from the kings of Kition, Amathus and Soli, who fled to the great king of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

in 390 BC to request support, Evagoras received less help from the Athenians than he had hoped for and in about 380 BCE, a Persian force besieged Salamis and Evagoras was forced to surrender. In the end, he remained king of Salamis until he was murdered in 374 BCE, but only by accepting his role as a vassal of Persia.

Evagoras I of Salamis introduced the Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BC. It was derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and is the earliest known alphabetic script to systematically write vowels as wel ...

to Cyprus. In other parts of the island, the Phoenician script (Kition) or the Cypriot syllabic alphabet were still used. Together with Egypt and Phoenicia, Cyprus rebelled against Persian rule again in 350 BCE, but the uprising was crushed by Artaxerxes III in 344 BCE.

Hellenistic period

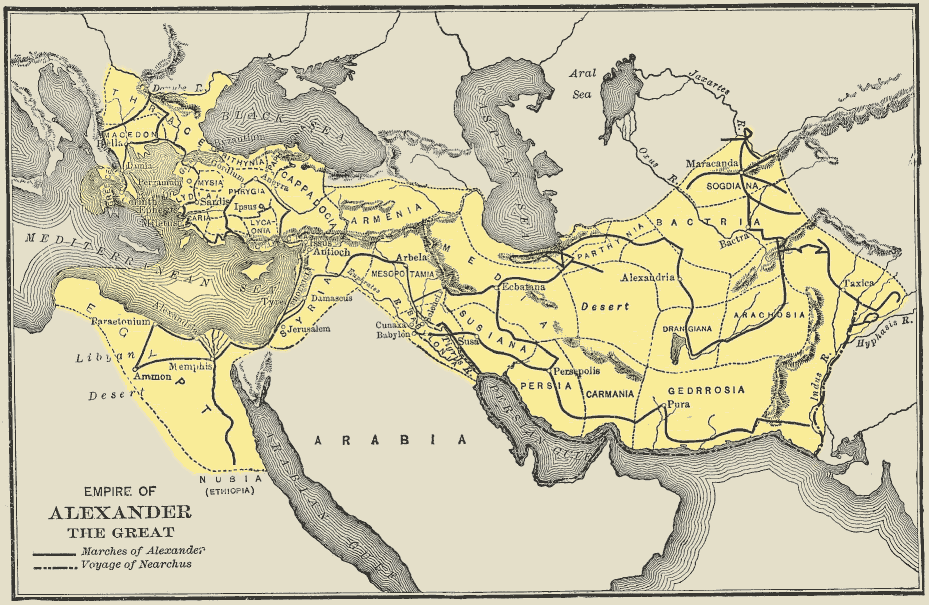

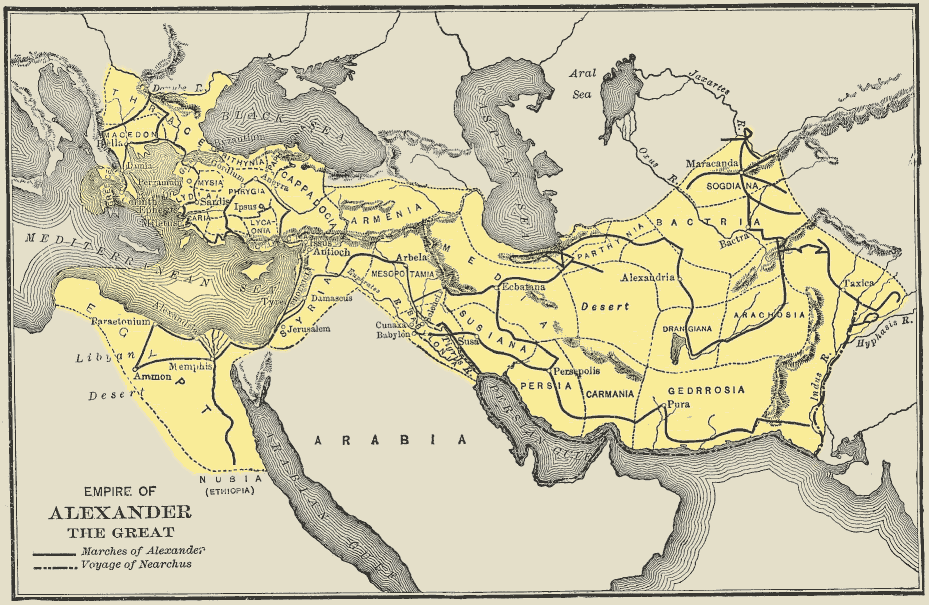

Alexander the Great

Long and sustained efforts to overthrow Persian rule proved unsuccessful and Cyprus remained a vassal of the Persian Empire until the Persians’ defeat by Alexander the Great. Alexander the Great (Alexander of Macedon and Alexander III of Macedon), was born in Pella in 356 BCE and died in Babylon in 323 BCE. Son of King Philip II and Olympias, he succeeded his father to the throne of Macedonia in 336 BCE at the age of 20. He was perhaps the greatest commander in history and led his army in a series of victorious battles, creating a vast empire that stretched from Greece toEgypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in Africa and to the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. The various kingdoms of Cyprus became allies of Alexander following his victorious campaigns at Granicus (334 BCE), Issus (333 BCE) and on the coast of Asia Minor, Syria and Phoenicia, where Persian naval bases were situated.

The Cypriot kings, learning of the victory of Alexander at Issus, and knowing that sooner or later, Alexander would be the new ruler of the island, since the occupation of Cyprus was necessary (along with that of Phoenicia) to open lines of communication to Egypt and Asia, rose up against their Persian overlords and made available to the fleet of Alexander the ships formerly in the service of Persia. There was a mutuality of interests: Alexander the Great increased the capacity of his fleet, and the Cypriot kings achieved political independence.

Siege of Tyre

From the area of Phoenicia, only Tyre resisted Alexander's control, and so he undertook a siege. The Cypriot fleet, together with Cypriot engineers, contributed much to the capture of this highly fortified city. Indeed, king Pnytagoras of Salamis, Androcles of Amathus, and Pasikratis of Soloi, took a personal part in the siege of Tyre. Tyre, then the most important Phoenician city, was built on a small island that was 700 metres from the shore and had two harbors, the Egyptian to the south and Sidonian to the north. The Cypriot kings, in command of 120 ships, each with a very experienced crew, provided substantial assistance to Alexander in the siege of this city, which lasted for seven months. During the final attack, the Cypriots managed to occupy the Sidonian harbour and the northern part of Tyre, while the Phoenicians loyal to Alexander occupied the Egyptian harbour. Alexander also attacked the city with siege engines by constructing a "mole", a strip of soil from the coast opposite Tyre, to the island where the city was built. In this operation, Alexander was helped by many Cypriot and Phoenician engineers who built earthworks on his behalf. Many siege engines battered the city from the "mole" and from "ippagoga" ships. Although they lost many quinqueremes, the Cypriots managed to help capture the city for Alexander. His gratitude was shown, for example, by the help he gave to Pnytagora, who seems to have been the main driver of this initiative to support Alexander, to incorporate the territory of the Cypriot kingdom of Tamassos into that of Salamis. The kingdom of Tamassos was then ruled by King Poumiaton of Kition who had purchased it for 50 talents from king Pasikypro. In 331 BCE, while Alexander was returning from Egypt, he stayed for a while in Tyre, where the Cypriot kings, wishing to reaffirm their trust and support for him, put on a great show of honour.Help to Amphoterus

Cypriot ships were also sent to help the admiral of Alexander the Great, Amphoterus (admiral).Alexander in Asia

Cyprus was an experienced seafaring nation and Alexander used the Cypriot fleet during his campaign into India; because the country had many navigable rivers, he included a significant number of shipbuilders and rowers from Cyprus, Egypt, Phoenicia and Caria in his military expedition. Cypriot forces were led by Cypriot princes such as Nikoklis, son of King Pasikrati of Solon, and Nifothona, son of King Pnytagora of Salamis. As Alexander took over control of the administrative region that had been the Persian Empire, he promoted Cypriots to high office and great responsibility; in particular, Stasanor of Soli was appointedsatrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of the Supreme Court and Drangon in 329 BCE and Stasander who was also from Soli appointed satrap of Aria

In music, an aria (, ; : , ; ''arias'' in common usage; diminutive form: arietta, ; : ariette; in English simply air (music), air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrument (music), instrumental or orchestral accompan ...

and Drangiana.

The hope of full independence for Cyprus following the fall of the Persian Empire, however, was slow to be realized. The mints of Salamis, Kition and Paphos began to stamp coins on Alexander's behalf rather than in the name of the local kings.

The policy of Alexander the Great on Cyprus and its kings soon became clear: to free them from Persian rule but to put them under his own authority. Away from the coast of Cyprus, the interior kingdoms were left largely independent and the kings maintained their autonomy, although not in issues such as mining rights. Alexander sought to make clear that he considered himself the master of the island, and abolished the currencies of the Cypriot kingdoms, replacing them by the minting of his own coins.

Death of Alexander

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, while still in his early thirties, put an end to Greek aspirations for global domination. The empire he had created was divided between his generals and successors, who immediately started fighting one another. The death of Alexander the Great marks the beginning of the Hellenistic period of Cypriot history. After the death of Alexander the Great, Cyprus passed on to the Ptolemaic rule. Still under Greek influence, Cyprus gained full access to the Greek culture and thus became fully hellenised.Egypt and Syria

The wars of Alexander's successors inevitably began to involve Cyprus, and focused on two claimants, Antigonus Monophthalmus in Syria (assisted by his son Demetrius Poliorcetes) and Ptolemy Lagus in Egypt. The Cypriot kings who, so far, had managed largely to maintain their kingdoms' independence, found themselves in a new and difficult position. This was because, as Cyprus became the focus of discord between Ptolemy and Antigonus, the kings of the island now had to make new choices and alliances. Some Cypriot kingdoms chose alliance with Ptolemy, others sided with the Antigonus, yet others tried to remain neutral, leading to inevitable controversy and confrontation. The largest city and kingdom of Cyprus then appears to have been Salamis, whose king was Nicocreon. Nicocreon strongly supported Ptolemy. According to Arrian, he had the support of Pasikratis of Solon, Nikoklis of Paphos and Androcles of Amathus. Other kings of Cyprus, however, including Praxippos of Lapithos and Kyrenia, the Poumiaton (Pygmalion) of Kition and Stasioikos of Marion, allied themselves with Antigonus. Against these, Nicocreon and other pro-Ptolemaic kings conducted military operations. Ptolemy sent military support to his allies, providing troops under the command of Seleucus and Menelaus. Lapithos-Kyrenia was occupied after a siege and Marion capitulated.Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

tells us that Amathus was forced to provide hostages, while Kition was laid siege to in about 315 BCE.

Ptolemy to Cyprus

Ptolemy entered Cyprus with further military forces in 312 BCE, captured and killed the king of Kition and arrested the pro-Antigonid kings of Marion and Lapithos-Kyrenia. He destroyed the city of Marion and annulled most of the former kingdoms of Cyprus. This crucial and decisive intervention by Ptolemy in 312 BCE gave more power to the kings of Solon and Paphos, and particularly to Nicocreon of Salamis, whom Ptolemy seems to have appreciated and trusted completely and who won the cities and the wealth of expelled kings. Salamis extended its authority throughout eastern, central and northern Cyprus, since Kition and Lapithos were absorbed into it and Tamassos already belonged. Furthermore, Nicocreon of Salamis took office as chief general in Cyprus with the blessing of Ptolemy, effectively making him master of the whole island. But the situation was fluid and the rulers of Soloi and Paphos had been kept in power. Soon, King Nicocles of Paphos was considered suspect; he was besieged and forced to suicide, and his entire family put to death (312 BCE). The following year (311 BCE) Nicocreon of Salamis died.Demetrius

After the intervention of Ptolemy in Cyprus, which subjugated the island, Antigonus and his son Demetrius reacted against the besiegers and Demetrius led a large military operation in Cyprus. Demetrius was born in 336 BC and initially fought under the command of his father in 317 BCE againstEumenes

Eumenes (; ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek general, satrap, and Diadoch, Successor of Alexander the Great. He participated in the Wars of Alexander the Great, serving as Alexander's personal secretary and later on as a battlefield commander. Eume ...

, where he particularly distinguished himself. In 307 BCE he liberated Athens, restoring democracy there and in 306 BCE, led the war against the Ptolemies. Wishing to use Cyprus as a base for attacks against Western Asia, he sailed from Cilicia to Cyprus with a large infantry force, cavalry and naval ships. Meeting no resistance, he landed in the Karpasia peninsula and occupied the cities Urania and Karpasia. Meanwhile, Menelaus, brother of Ptolemy I Soter, the new general of the island, gathered his forces at Salamis. Ptolemy arrived to aid his brother, but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Salamis, after which Cyprus came under Antigonid control.

Demetrius's father Antigonus Monophthalmus was killed in the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC and Demetrius, having reorganized the army, was proclaimed King of Macedon, but was evicted by Lysimachus and Pyrrhus. Cyprus came once again under Ptolemaic control in 294 BC and mostly remained under Ptolemaic rule until 58 BC, when it became a Roman province. It was ruled by a series of governors sent from Egypt and sometimes formed a minor Ptolemaic kingdom during the power struggles of the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Also, the Seleucid Empire briefly took the island over during the Sixth Syrian War

The Syrian Wars were a series of six wars between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom, Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, Diadochi, successor states to Alexander the Great's empire, during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC over the region then c ...

, but gave the island back as part of a treaty arranged by the Romans. During this time, Cyprus forged strong commercial relationships with Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, two of the most important commercial centres of antiquity.

Full Hellenisation of Cyprus took place under Ptolemaic rule. During this period, the Eteocypriot and Phoenician languages disappeared, together with the old Cypriot syllabic script, which was replaced by the Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BC. It was derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and is the earliest known alphabetic script to systematically write vowels as wel ...

. A number of cities were founded during this time. For example, Arsinoe was founded between old and new Paphos by Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (, ''Ptolemaîos Philádelphos'', "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the G ...

. Ptolemaic rule was rigid and exploited the island's resources to the utmost, particularly timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

.

A great contemporary figure of Cypriot letters was the philosopher Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; , ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic philosopher from Kition, Citium (, ), Cyprus.

He was the founder of the Stoicism, Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. B ...

who was born at Kition about 336 BCE and founded the famous Stoic School of Philosophy at Athens, where he died about 263 BCE.

Roman period

Cyprus became aRoman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

in 58 BCE. This came about, according to Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, because Publius Clodius Pulcher held a grudge against Ptolemy of Cyprus. The renowned Stoic and strict constitutionalist Cato the Younger was sent to annex Cyprus and organize it under Roman law. Cato was relentless in protecting Cyprus against the rapacious tax farmers that normally plagued the provinces of the Republican period. After the civil wars that ended the Roman Republic, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

gave the island to Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

of Egypt and their daughter Cleopatra Selene, but it became a Roman province again after his defeat at the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

in 31 BCE. From 22 BCE onwards, Cyprus was a senatorial province "divided into four districts centred around Paphus, Salamis, Amathus and Lapethus."Talbert, Richard J A (Ed), 1985. ''Atlas of Classical History''. Routledge. Roman Cyprus, pp 156–7. After the reforms of Diocletian

Diocletian ( ; ; ; 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed Jovius, was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Diocles to a family of low status in the Roman province of Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia. As with other Illyri ...

it was placed under the Diocese of Oriens.

The '' Pax Romana'' (Roman peace) was only twice disturbed in Cyprus in three centuries of Roman occupation. The first serious interruption occurred in 115–16, when a revolt by Jews inspired by Messianic hopes broke out. Their leader was Artemion, a Jew with a Hellenised name, as was the practice of the time. The island suffered great losses in this war; it is believed that 240,000 Greek and Roman civilians were killed. Although this number may be exaggerated, there were few or no Roman troops stationed on the island to suppress the insurrection as the rebels wreaked havoc. After forces were sent to Cyprus and the uprising was put down, a law was passed that no Jews were permitted to land on Cyprian soil, even in cases of shipwreck.

Turmoil sprang up two centuries later in 333–4, when a local official Calocaerus revolted against Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

. This rebellion ended with the arrival of troops led by Flavius Dalmatius and the death of Calocaerus.

Olive oil trade in the late Roman period

Olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

was a very important part of daily life in the Mediterranean in the Roman Period. It was used for food, as a fuel for lamps, and as a basic ingredient in things like medicinal ointment, bath oils, skin oils, soaps, perfumes and cosmetics. Even before the Roman Period, Cyprus was known for its olive oil, as indicated by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

when he said that "in fertility Cyprus is not inferior to any one of the islands, for it produces both good wine and good oil".Papacostas, T., 2001, ''The Economy of Late Antique Cyprus.'' In: ''Economy and Exchange in the East Mediterranean during Late Antiquity''. Proceedings of a conference at Somerville College, Oxford, 29 May 1999, edited by S. Kingsley and M. Decker, 107–28. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

There is evidence for both a local trade of Cypriot oil and for a larger trading network that may have reached as far as the Aegean, although most Cypriot oil was probably limited to the Eastern Mediterranean. Many olive oil presses have been found on Cyprus, and not just in rural areas, where they might be expected for personal, local use. They have been found in some of the larger coastal cities as well, including Paphos, Curium and Amathus. In Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Egypt, there is a large presence of a type of amphora

An amphora (; ; English ) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land ...

made in Cyprus known as Late Roman 1 or LR1 that was used to carry oil. This indicates that a lot of Cypriot oil was being imported into Egypt. There is also evidence for Cypriot trade with Cilicia and Syria.

Olive oil was also traded locally, around the island. Amphorae found at Alaminos-Latourou Chiftlik and Dreamer's Bay, indicate that the oil produced in these areas was mostly used locally or shipped to nearby towns. The amphora found on a contemporary shipwreck at Cape Zevgari indicate that the vessel, a typical small merchant ship, was carrying oil and there is evidence from the location of the wreck and the ship itself that it was traveling only a short distance, probably west around the island.Leidwanger, J. 2007, ''Two Late Roman Wrecks from Southern Cyprus.'' IJNA 36: 308–16.

Christianity

Roman Cyprus

Roman Cyprus was a small senatorial province within the Roman Empire. While it was a small province, it possessed several well known religious sanctuaries and figured prominently in Eastern Mediterranean trade, particularly the production and trad ...

was visited by the Apostles Paul, Barnabas

Barnabas (; ; ), born Joseph () or Joses (), was according to tradition an early Christians, Christian, one of the prominent Disciple (Christianity), Christian disciples in Jerusalem. According to Acts 4:36, Barnabas was a Cypriot Jews, Cyprio ...

and St. Mark, who came to the island at the beginning of their first missionary journey in 45 AD, according to Christian tradition, converting the people of Cyprus to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and founding the Church of Cyprus. After their arrival in Salamis, they proceeded to Paphos where they converted the Roman governor Sergius Paulus to Christ. In the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

book of Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

, author St. Luke describes how a Jewish magician named Bar-Jesus

Elymas (; ; ), also known as Bar-Jesus (, , ), is a character described in the Acts of the Apostles, chapter 13, where he is referred to as a ''mágos'' (μάγος), which the King James Version of the Bible, King James Bible translates as "sorce ...

(Elymas) was obstructing the Apostles in their preaching of the Gospel. Paul rebuked him, announcing that he would temporarily become blind due to God's judgment. Paul's prediction immediately came true. As a result of this, Sergius Paulus became a believer, being astonished at the teaching of the Lord. In this way, Cyprus became the first country in the world to be governed by a Christian ruler.

Paul is credited with underpinning claims for ecclesiastical independence from Antioch. At least three Cypriot bishops (the sees of Salamis, Tremithus, and Paphos) took part in the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

in 325, and twelve Cypriot bishops were present at the Council of Sardica in 344. Early Cypriot Saints include: St. Heracleidius, St. Spiridon, St. Hilarion and St. Epiphanius.

Several earthquakes led to the destruction of Salamis at the beginning of the 4th century, at the same time drought and famine hit the island.

In 431 AD, the Church of Cyprus achieved its independence from the Patriarch of Antioch

The Patriarch of Antioch is a traditional title held by the bishop of Antioch (modern-day Antakya, Turkey). As the traditional "overseer" (, , from which the word ''bishop'' is derived) of the first gentile Christian community, the position has ...

at the First Council of Ephesus. Emperor Zeno

Zeno may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Zeno (surname)

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 B ...

granted the archbishop of Cyprus the right to carry a sceptre instead of a pastoral staff.

See also

* List of earthquakes in Cyprus * Pottery of ancient Cyprus * Ancient Cypriot artNotes

Further reading

* Cobham, C D, 1908. ''Excerpta Cypria, materials for a history of Cyprus''. Cambridge. Includes the Classical Sources. * * Hunt, D, 1990. ''Footprints in Cyprus''. London, Trigraph. * Leidwanger, J, 2007, ''Two Late Roman Wrecks from Southern Cyprus.'' IJNA 36: pp 308–16. * Leonard, J. and Demesticha, S, 2004. ''Fundamental Links in the Economic Chain: Local Ports and International trade in Roman and Early Christian Cyprus.'' In: ''Transport Amphorae and Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean'', Acts of the International Colloquium at the Danish Institute at Athens, September 26–9, 2002, edited by J. Eiring and J. Lund, Aarhus, Aarhus University Press: pp 189–202. * Papacostas, T, 2001, ''The Economy of Late Antique Cyprus.'' In: ''Economy and Exchange in the East Mediterranean during Late Antiquity''. Proceedings of a conference at Somerville College, Oxford, 29 May 1999, edited by S. Kingsley and M. Decker, Oxford, Oxbow Books: pp 107–28. * Şevketoğlu, M. 2015, ”Akanthou- Arkosykos, a ninth Millenium BC coastal settlement in Cyprus” in Environmental Archaeology, Association for Environmental Archaeology * Tatton-Brown, Veronica, 1979. ''Cyprus BC, 7000 years of history''. London, British Museum Publications. * Tyree, E L, 1996. * Winbladh, M.-L., Cypriote Antiquities in the Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm 1977. * Winbladh, M-L., 'Adventuring with Cyprus. A Chronicle of the Swedish Cyprus Expedition 1927 – 1931' in The Northern Face of Cyprus. New Studies in Cypriot Archaeology and Art History, eds. Hazar Kaba & Summerer, Latife, Istanbul 2016 * Winbladh, M.-L., Kıbrıs Macerası – The Cyprus Adventure – Περιπετεια στην Κυπρο (1927–1931), Galeri Kültür Kitabevi, Lefkoşa 2013 * Winbladh, M.-L., The Origins of The Cypriots. With Scientific Data of Archaeology and Genetics, Galeri Kultur Publishing, Lefkoşa 2020 * Winbladh, M.-L., Adventures of an archaeologist. Memoirs of a museum curator, AKAKIA Publications, London 2020 * Voskos, I. & Knapp A.B. 2008, ”Cyprus at the End of the Late Bronze Age: Crisis and Colonization or Continuity and Hybridization?” American Journal of Archaeology 112External links

Ancient History of Cyprus, by the Cypriot government

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ancient History of Cyprus Phoenician colonies