American Philosophy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The ''

Retrieved on May 24, 2009 The philosophy of the Founding Fathers of the United States is largely seen as an extension of the European Enlightenment. A small number of philosophies are known as American in origin, namely

Transcendentalism in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against

Transcendentalism in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against

Retrieved on July 30, 2008

Pragmatism continued its influence into the 20th century, and Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana was one of the leading proponents of pragmatism and realism in this period. He held that

Pragmatism continued its influence into the 20th century, and Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana was one of the leading proponents of pragmatism and realism in this period. He held that

Retrieved on September 7, 2009 Some academic philosophers have been highly critical of the quality and intellectual rigor of Rand's work,"The Winnowing of Ayn Rand" by Roderick Long

Retrieved July 10, 2010"The philosophical art of looking out number one" at heraldscotland

Retrieved July 10, 2010 but she remains a popular, albeit controversial, figure within American culture."Ayn Rand" at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Retrieved July 10, 2010

Retrieved July 10, 2010

Saul Kripke, a student of Quine's at

Saul Kripke, a student of Quine's at

In 1971 John Rawls published '' A Theory of Justice'', which puts forth his view of '' justice as fairness'', a version of

In 1971 John Rawls published '' A Theory of Justice'', which puts forth his view of '' justice as fairness'', a version of

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as

Towards the end of the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are

Towards the end of the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are  Noted American legal philosophers

Noted American legal philosophers

American Philosophical Association

American Philosophical Society

Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy

{{United States topics American literature Culture of the United States Cultural history of the United States

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''IEP'') is a scholarly online encyclopedia with around 900 articles about philosophy, philosophers, and related topics. The IEP publishes only peer review, peer-reviewed and blind-refereed original p ...

'' notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can nevertheless be seen as both reflecting and shaping collective American identity over the history of the nation"."American philosophy" at the Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyRetrieved on May 24, 2009 The philosophy of the Founding Fathers of the United States is largely seen as an extension of the European Enlightenment. A small number of philosophies are known as American in origin, namely

pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics� ...

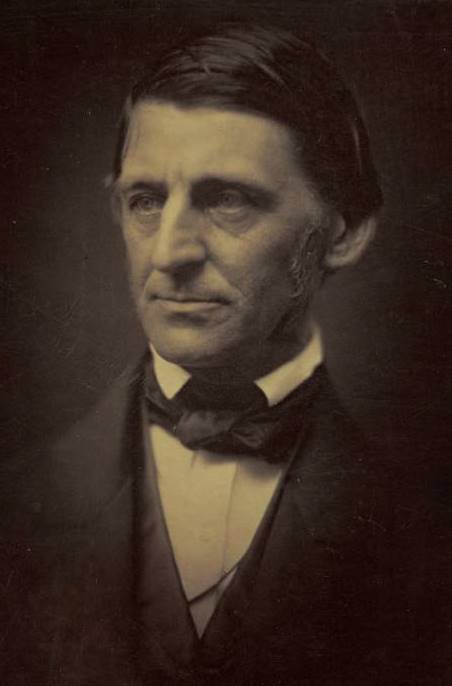

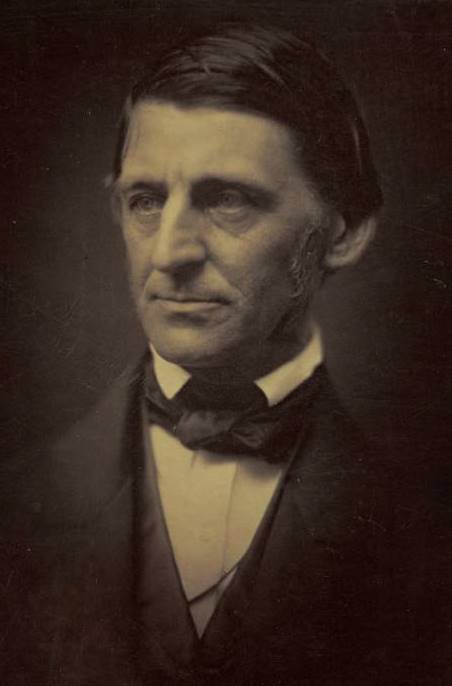

and transcendentalism, with their most prominent proponents being the philosophers William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

respectively.

17th century

Although there had been various people, communities, and nations inhabiting the territories that would later become the United States, all of whom engaged with philosophical questions such as the nature of the self, interpersonal relationships, and origins and destinies, most histories of the American philosophical tradition have traditionally begun with European colonization, especially with the arrival of the Puritans inNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. Documents such as the Mayflower Compact (1620), followed by the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut

The Fundamental Orders were adopted by the Connecticut Colony council on . The fundamental orders describe the government set up by the Connecticut River New England town, towns, setting its structure and powers and was a driven attempt for the ...

(1639) and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), made manifest basic socio-political positions, which served as foundations for the newly established communities. These set the early colonial philosophy into a religious tradition (Puritan Providentialism), and there was also an emphasis on the relationship between the individual and the community.

Thinkers such as John Winthrop emphasized the public life over the private. Holding that the former takes precedence over the latter, while other writers, such as Roger Williams (co-founder of Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

) held that religious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

was more integral than trying to achieve religious homogeneity in a community.

18th century

18th-century American philosophy may be broken into two halves, the first half being marked by the theology of Reformed PuritanCalvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

influenced by the Great Awakening as well as Enlightenment natural philosophy, and the second by the native moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

of the American Enlightenment taught in American colleges. They were used "in the tumultuous years of the 1750s and 1770s" to "forge a new intellectual culture for the United states", which led to the American incarnation of the European Enlightenment that is associated with the political thought of the Founding Fathers.

The 18th century saw the introduction of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

and the Enlightenment philosophers Descartes, Newton, Locke, Wollaston, and Berkeley to Colonial British America. Two native-born Americans, Samuel Johnson and Jonathan Edwards, were first influenced by these philosophers; they then adapted and extended their Enlightenment ideas to develop their own American theology and philosophy. Both were originally ordained Puritan Congregationalist ministers who embraced much of the new learning of the Enlightenment. Both were Yale educated and Berkeley influenced idealists

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is enti ...

who became influential college presidents. Both were influential in the development of American political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

and the works of the Founding Fathers. But Edwards based his reformed Puritan theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

on Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

doctrine, while Johnson converted to the Anglican episcopal religion (the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

), then based his new American moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

on William Wollaston's Natural Religion. Late in the century, Scottish innate or common sense realism replaced the native schools of these two rivals in the college philosophy curricula of American colleges; it would remain the dominant philosophy in American academia up to the Civil War.

Introduction of the Enlightenment into America

The first 100 years or so of college education in the American Colonies were dominated in New England by the Puritan theology of William Ames and "the sixteenth-century logical methods of Petrus Ramus." Then in 1714, a donation of 800 books from England, collected by Colonial Agent Jeremiah Dummer, arrived at Yale.Ellis, Joseph J., ''The New England Mind in Transition: Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, 1696–1772,'' Yale University Press, 1973, p. 34 They contained what became known as "The New Learning", including "the works of Locke, Descartes, Newton, Boyle, andShakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

", and other Enlightenment era authors not known to the tutors and graduates of Puritan Yale and Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

colleges. They were first opened and studied by an eighteen-year-old graduate student from Guilford, Connecticut, the young American Samuel Johnson, who had also just found and read Lord Francis Bacon's 1605 book '' Advancement of Learning.'' Johnson wrote in his ''Autobiography'', "All this was like a flood of day to his low state of mind" and that "he found himself like one at once emerging out of the glimmer of twilight into the full sunshine of open day." He now considered what he had learned at Yale "nothing but the scholastic cobwebs of a few little English and Dutch systems that would hardly now be taken up in the street."

Johnson was appointed tutor at Yale in 1716. He began to teach the Enlightenment curriculum there, and thus began the American Enlightenment. One of his students for a brief time was a fifteen-year-old Jonathan Edwards. "These two brilliant Yale students of those years, each of whom was to become a noted thinker and college president, exposed the fundamental nature of the problem" of the "incongruities between the old learning and the new." But each had a quite different view on the issues of predestination versus freewill, original sin versus the pursuit of happiness through practicing virtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

, and the education of children.

Reformed Calvinism

Jonathan Edwards was "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as " Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the First Great Awakening), Edwards emphasized "the absolute sovereignty of God and the beauty of God's holiness." Working to unite ChristianPlatonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

with an empiricist epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

, with the aid of Newtonian physics, Edwards was deeply influenced by George Berkeley, himself an empiricist, and Edwards derived his importance of the immaterial for the creation of human experience from Bishop Berkeley.

The non-material mind consists of understanding and will, and it is understanding, interpreted in a Newtonian framework, that leads to Edwards' fundamental metaphysical category of Resistance. Whatever features an object may have, it has these properties because the object resists. Resistance itself is the exertion of God's power, and it can be seen in Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body re ...

, where an object is "unwilling" to change its current state of motion; an object at rest will remain at rest and an object in motion will remain in motion.

Though Edwards reformed Puritan theology using Enlightenment ideas from natural philosophy, Locke, Newton, and Berkeley, he remained a Calvinist and hard determinist. Jonathan Edwards also rejected the freedom of the will, saying that "we can do as we please, but we cannot please as we please." According to Edwards, neither good works nor self-originating faith lead to salvation, but rather it is the unconditional grace of God which stands as the sole arbiter of human fortune.

Enlightenment

While the 17th- and early 18th-century American philosophical tradition was decidedly marked by religious themes and the Reformation reason of Ramus, the 18th century saw more reliance onscience

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and the new learning of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, along with an idealist belief in the perfectibility of human beings through teaching ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

and moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

, laissez-faire economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, and a new focus on political matters.

Samuel Johnson has been called "The Founder of American Philosophy" and the "first important philosopher in colonial America and author of the first philosophy textbook published there". He was interested not only in philosophy and theology, but in theories of education, and in knowledge classification schemes, which he used to write encyclopedias, develop college curricula, and create library classification systems.

Johnson was a proponent of the view that "the essence of true religion is morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

", and believed that "the problem of denominationalism" could be solved by teaching a non-denominational common moral philosophy acceptable to all religions. So he crafted one. Johnson's moral philosophy was influenced by Descartes and Locke, but more directly by William Wollaston's 1722 book '' Religion of Nature Delineated'' and the idealist philosopher of George Berkeley, with whom Johnson studied while Berkeley was in Rhode Island between 1729 and 1731. Johnson strongly rejected Calvin's doctrine of Predestination and believed that people were autonomous moral agents endowed with freewill and Lockean natural rights. His fusion philosophy of Natural Religion and Idealism, which has been called "American Practical Idealism", was developed as a series of college textbooks in seven editions between 1731 and 1754. These works, and his dialogue ''Raphael, or The Genius of the English America, ''written at the time of the Stamp Act crisis, go beyond his Wollaston and Berkeley influences; ''Raphael ''includes sections on economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, the teaching of children, and political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

.

His moral philosophy is defined in his college textbook ''Elementa Philosophica'' as "the Art of pursuing our highest Happiness by the practice of virtue". It was promoted by President Thomas Clap of Yale, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

and Provost William Smith at The Academy and College of Philadelphia, and taught at King's College (now Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

), which Johnson founded in 1754. It was influential in its day: it has been estimated that about half of American college students between 1743 and 1776, and over half of the men who contributed to the ''Declaration of Independence'' or debated it were connected to Johnson's American Practical Idealism moral philosophy. Three members of the Committee of Five who edited the '' Declaration of Independence'' were closely connected to Johnson: his educational partner, promoter, friend, and publisher Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, his King's College student Robert R. Livingston of New York, and his son William Samuel Johnson's legal protegee and Yale treasurer Roger Sherman of Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

. Johnson's son William Samuel Johnson was the Chairman of the Committee of Style that wrote the U.S. Constitution: edits to a draft version are in his hand in the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

.

Founders' political philosophy

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil andpolitical philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

. Many of the Founding Fathers wrote extensively on political issues, including John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, John Dickinson, Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, John Jay

John Jay (, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, diplomat, signatory of the Treaty of Paris (1783), Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, and James Madison. In continuing with the chief concerns of the Puritans in the 17th century, the Founding Fathers debated the interrelationship between God, the state, and the individual. Resulting from this were the '' United States Declaration of Independence'', passed in 1776, and the ''United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

'', ratified in 1788.

The Constitution sets forth a federal and republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

an form of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

that is marked by a balance of powers accompanied by a checks and balances system between the three branches of government: a judicial branch, an executive branch led by the President, and a legislative branch

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the authority, legal authority to make laws for a Polity, political entity such as a Sovereign state, country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with th ...

composed of a bicameral legislature where the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

is the lower house

A lower house is the lower chamber of a bicameral legislature, where the other chamber is the upper house. Although styled as "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or otherwise e ...

and the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

is the upper house

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

.

Although the ''Declaration of Independence'' does contain references to the Creator, the God of Nature, Divine Providence, and the Supreme Judge of the World, the Founding Fathers were not exclusively theistic. Some professed personal concepts of deism, as was characteristic of other European Enlightenment thinkers, such as Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre ferv ...

, François-Marie Arouet (better known by his pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

), and Rousseau. However, an investigation of 106 contributors to the ''Declaration of Independence'' between September 5, 1774, and July 4, 1776, found that only two men (Franklin and Jefferson), both American Practical Idealists in their moral philosophy, might be called quasi-deists or non-denominational Christians; all the others were publicly members of denominational Christian churches. Even Franklin professed the need for a "public religion" and would attend various churches from time to time. Jefferson was vestryman at the evangelical Calvinistical Reformed Church of Charlottesville, Virginia, a church he himself founded and named in 1777, suggesting that at this time of life he was rather strongly affiliated with a denomination and that the influence of Whitefield and Edwards reached even into Virginia. But the founders who studied or embraced Johnson, Franklin, and Smith's non-denominational moral philosophy were at least influenced by the deistic tendencies of Wollaston's Natural Religion, as evidenced by "the Laws of Nature, and Nature's God" and "the pursuit of Happiness" in the ''Declaration''.

An alternate moral philosophy to the domestic American Practical Idealism, called variously Scottish Innate Sense moral philosophy (by Jefferson), Scottish Commonsense Philosophy, or Scottish common sense realism, was introduced into American Colleges in 1768 by John Witherspoon, a Scottish immigrant and educator who was invited to be President of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

). He was a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

minister and a delegate who joined the Continental Congress just days before the ''Declaration'' was debated. His moral philosophy was based on the work of the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson, who also influenced John Adams. When President Witherspoon arrived at the College of New Jersey in 1768, he expanded its natural philosophy offerings, purged the Berkeley adherents from the faculty, including Jonathan Edwards Jr., and taught his own Hutcheson-influenced form of Scottish innate sense moral philosophy. Some revisionist commentators, including Garry Wills' ''Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence'', claimed in the 1970s that this imported Scottish philosophy was the basis for the founding documents of America. However, other historians have questioned this assertion. Ronald Hamowy published a critique of Garry Wills's ''Inventing America'', concluding that "the moment ills'sstatements are subjected to scrutiny, they appear a mass of confusions, uneducated guesses, and blatant errors of fact." Another investigation of all of the contributors to the '' United States Declaration of Independence'' suggests that only Jonathan Witherspoon and John Adams embraced the imported Scottish morality. While Scottish innate sense realism would in the decades after the Revolution become the dominant moral philosophy in classrooms of American academia for almost 100 years, it was not a strong influence at the time of the ''Declaration'' was crafted. Johnson's American Practical Idealism and Edwards' Reform Puritan Calvinism were far stronger influences on the men of the Continental Congress and on the ''Declaration''.

Thomas Paine, the English intellectual, pamphleteer, and revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

who wrote ''Common Sense'' and '' Rights of Man'' was an influential promoter of Enlightenment political ideas in America, though he was not a philosopher. ''Common Sense'', which has been described as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era", provides justification for the American revolution and independence from the British Crown. Though popular in 1776, historian Pauline Maier cautions that, "Paine's influence was more modest than he claimed and than his more enthusiastic admirers assume."

In summary, "in the middle eighteenth century," it was "the collegians who studied" the ideas of the new learning and moral philosophy taught in the Colonial colleges who "created new documents of American nationhood." It was the generation of "Founding Grandfathers", men such as President Samuel Johnson, President Jonathan Edwards, President Thomas Clap, Benjamin Franklin, and Provost William Smith, who "first created the idealistic moral philosophy of 'the pursuit of Happiness', and then taught it in American colleges to the generation of men who would become the Founding Fathers."

19th century

The 19th century saw the rise ofRomanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

in America. The American incarnation of Romanticism was transcendentalism and it stands as a major American innovation. The 19th century also saw the rise of the school of pragmatism, along with a smaller, Hegelian philosophical movement led by George Holmes Howison that was focused in St. Louis, though the influence of American pragmatism far outstripped that of the small Hegelian movement.

Other reactions to materialism included the " Objective idealism" of Josiah Royce

Josiah Royce (; November 20, 1855 – September 14, 1916) was an American Pragmatism, pragmatist and objective idealism, objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his joining of pragmatis ...

, and the " Personalism," sometimes called "Boston personalism," of Borden Parker Bowne.

Transcendentalism

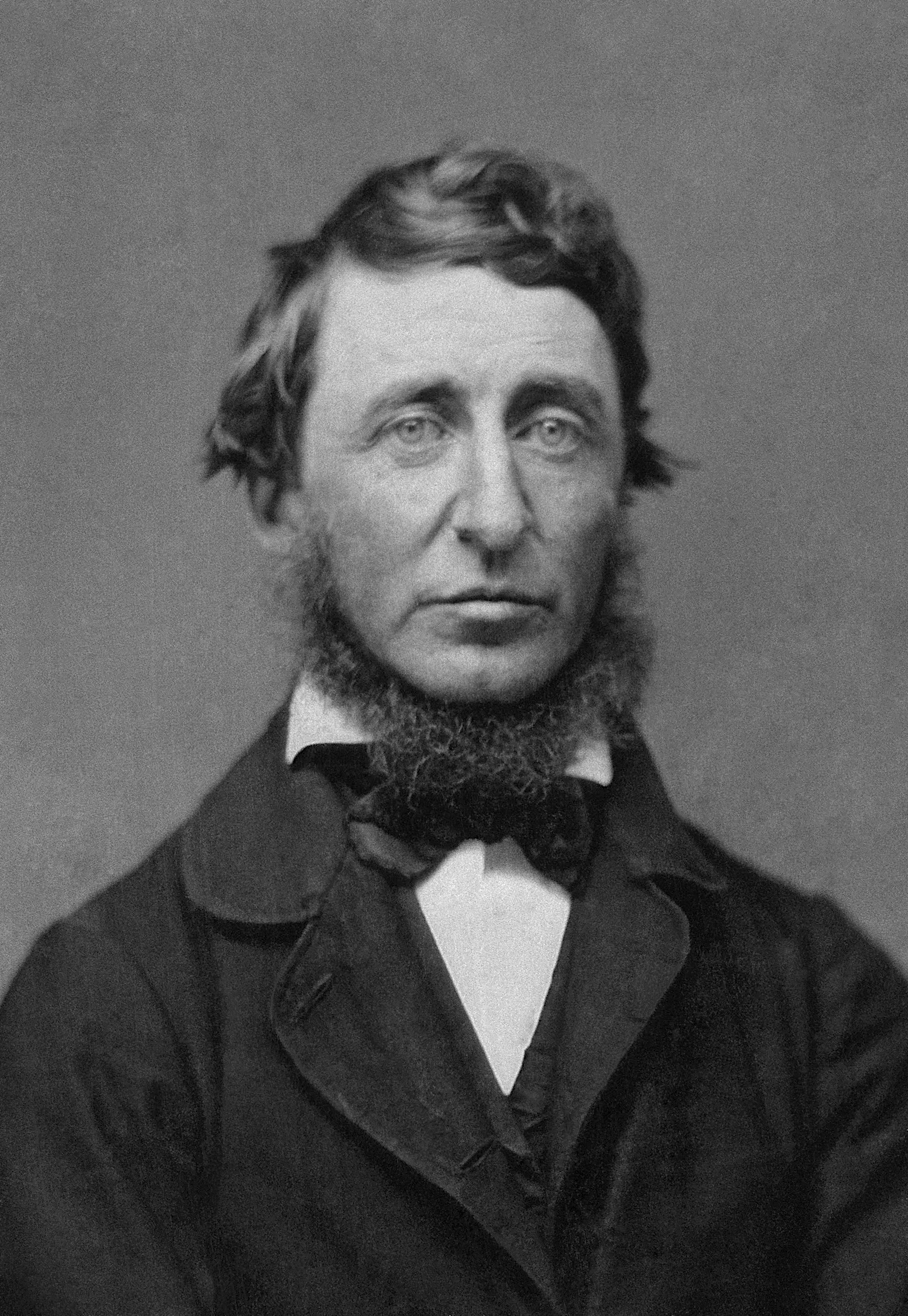

Transcendentalism in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against

Transcendentalism in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

and intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, development, and exercise of the intellect, and is identified with the life of the mind of the intellectual. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''intellectualism'' in ...

in general and the mechanistic, reductionistic worldview in particular. Transcendentalism is marked by the holistic belief in an ideal spiritual state that 'transcends' the physical and empirical, and this perfect state can only be attained by one's own intuition and personal reflection, as opposed to either industrial progress and scientific advancement or the principles and prescriptions of traditional, organized religion. The most notable transcendentalist writers include Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

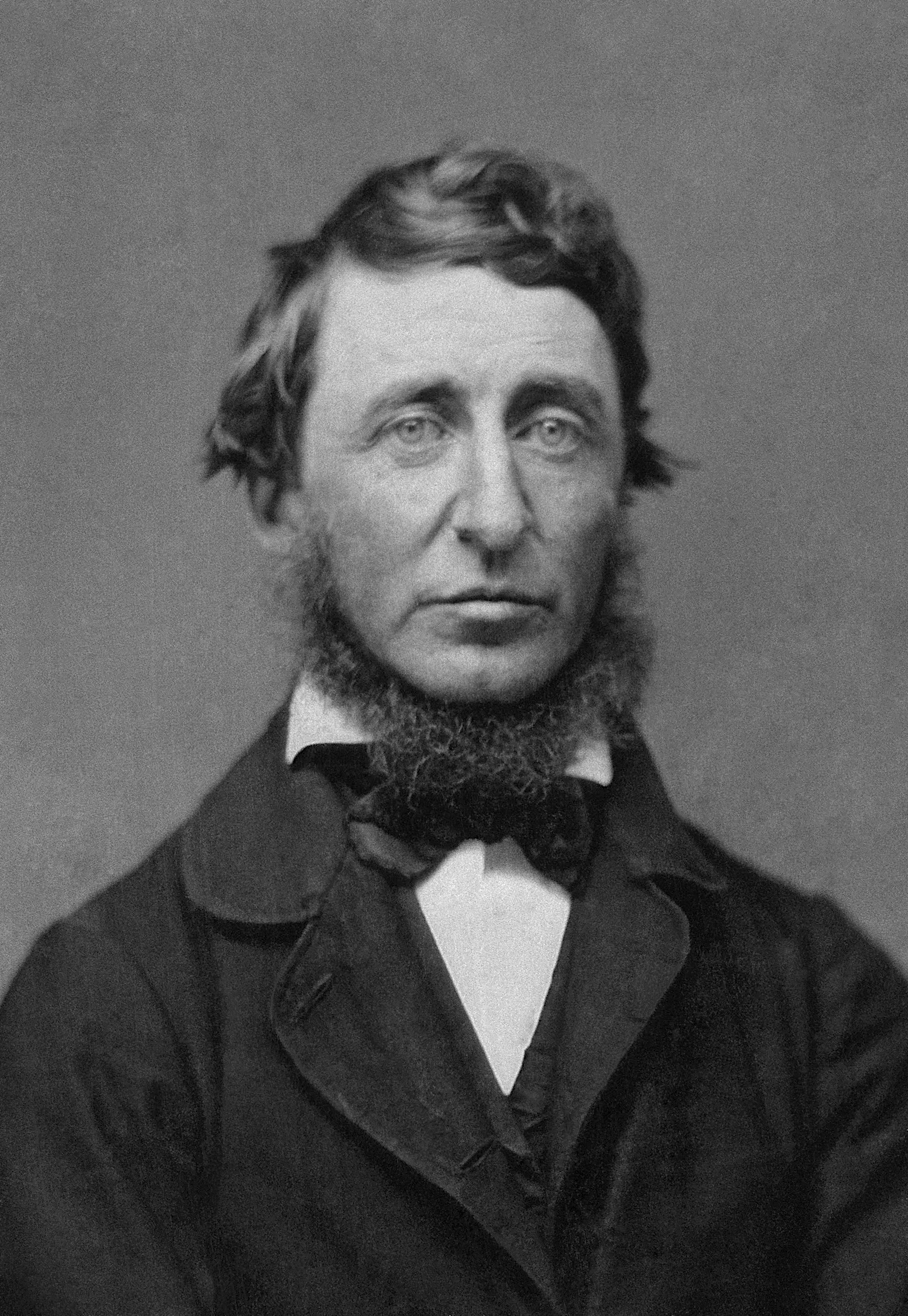

, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller.

The transcendentalist writers all desired a deep return to nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

, and believed that real, true knowledge is intuitive and personal and arises out of personal immersion and reflection in nature, as opposed to scientific knowledge that is the result of empirical sense experience. Influenced by Emerson and the importance of nature, Charles Stearns Wheeler built a shanty at Flint's Pond in 1836. Considered the first Transcendentalist outdoor living experiment, Wheeler used his shanty during his summer vacations from Harvard from 1836 to 1842. Thoreau stayed at Wheeler's shanty for six weeks during the summer of 1837, and got the idea that he wanted to build his own cabin (later realized at Walden in 1845).

Things such as scientific tools, political institutions, and the conventional rules of morality as dictated by traditional religion need to be transcended. This is found in Henry David Thoreau's 1854 book '' Walden; or, Life in the Woods'' where transcendence is achieved through immersion in nature and the distancing of oneself from society.

Darwinism in America

The release ofCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's evolutionary theory in his 1859 publication of '' On the Origin of Species'' had a strong impact on American philosophy. John Fiske and Chauncey Wright both wrote about and argued for the re-conceiving of philosophy through an evolutionary lens. They both wanted to understand morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

and the mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

in Darwinian terms, setting a precedent for evolutionary psychology

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in psychology that examines cognition and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify human psychological adaptations with regard to the ancestral problems they evolved ...

and evolutionary ethics.

Darwin's biological theory was also integrated into the social and political philosophies of English thinker Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

and American philosopher William Graham Sumner. Herbert Spencer, who coined the oft-misattributed term "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

," believed that societies were in a struggle for survival, and that groups within society are where they are because of some level of fitness. This struggle is beneficial to human kind, as in the long run the weak will be weeded out and only the strong will survive. This position is often referred to as Social Darwinism, though it is distinct from the eugenics movements with which social darwinism is often associated. The laissez-faire beliefs of Sumner and Spencer do not advocate coercive breeding to achieve a planned outcome.

Sumner, much influenced by Spencer, believed along with the industrialist Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

that the social implication of the fact of the struggle for survival is that laissez-faire capitalism is the natural political-economic system and is the one that will lead to the greatest amount of well-being. William Sumner, in addition to his advocacy of free markets, also espoused anti-imperialism (having been credited with coining the term "ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead o ...

"), and advocated for the gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

.

Pragmatism

The most influential school of thought that is uniquely American ispragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics� ...

. It began in the late nineteenth century in the United States with Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

, William James, and John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and Education reform, educational reformer. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.

The overridi ...

. Pragmatism begins with the idea that belief is that upon which one is willing to act. It holds that a proposition's meaning is the consequent form of conduct or practice that would be implied by accepting the proposition as true."Pragmatism" at IEPRetrieved on July 30, 2008

Charles Sanders Peirce

Polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, logician, mathematician, philosopher, and scientist Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

(1839–1914) coined the term "pragmatism" in the 1870s. He was a member of The Metaphysical Club, which was a conversational club of intellectuals that also included Chauncey Wright, future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and William James. In addition to making profound contributions to semiotics

Semiotics ( ) is the systematic study of sign processes and the communication of meaning. In semiotics, a sign is defined as anything that communicates intentional and unintentional meaning or feelings to the sign's interpreter.

Semiosis is a ...

, logic, and mathematics, Peirce wrote what are considered to be the founding documents of pragmatism, " The Fixation of Belief" (1877) and "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878).

In "The Fixation of Belief" Peirce argues for the superiority of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

in settling belief on theoretical questions. In "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" Peirce argued for pragmatism as summed up in that which he later called the pragmatic maxim: "Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object". Peirce emphasized that a conception is general, such that its meaning is not a set of actual, definite effects themselves. Instead the conception of an object is equated to a conception of that object's effects to a general extent of their conceivable implications for informed practice. Those conceivable practical implications are the conception's meaning.

The maxim is intended to help fruitfully clarify confusions caused, for example, by distinctions that make formal but not practical differences. Traditionally one analyzes an idea into parts (his example: a definition of truth as a sign's correspondence to its object). To that needful but confined step, the maxim adds a further and practice-oriented step (his example: a definition of truth as sufficient investigation's destined end).

It is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the formation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the use and improvement of verification. Typical of Peirce is his concern with inference to explanatory hypotheses as outside the usual foundational alternative between deductivist rationalism and inductivist empiricism, though he himself was a mathematician of logic and a founder of statistics.

Peirce's philosophy includes a pervasive three-category system, both fallibilism and anti-skeptical belief that truth is discoverable and immutable, logic as formal semiotic (including semiotic elements and classes of signs, modes of inference, and methods of inquiry along with pragmatism and critical common-sensism), Scholastic realism, theism, objective idealism, and belief in the reality of continuity of space, time, and law, and in the reality of absolute chance, mechanical necessity, and creative love as principles operative in the cosmos and as modes of its evolution.

William James

William James (1842–1910) was "an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy." He is famous as the author of '' The Varieties of Religious Experience'', his monumental tome '' The Principles of Psychology'', and his lecture " The Will to Believe." James, along with Peirce, saw pragmatism as embodying familiar attitudes elaborated into a radical new philosophical method of clarifying ideas and thereby resolving dilemmas. In his 1910 '' Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking,'' James paraphrased Peirce's pragmatic maxim as follows: He then went on to characterize pragmatism as promoting not only a method of clarifying ideas but also as endorsing a particular theory of truth. Peirce rejected this latter move by James, preferring to describe the pragmatic maxim only as a maxim of logic and pragmatism as a methodological stance, explicitly denying that it was a substantive doctrine or theory about anything, truth or otherwise. James is also known for his radical empiricism which holds that relations between objects are as real as the objects themselves. James was also a pluralist in that he believed that there may actually be multiple correct accounts of truth. He rejected the correspondence theory of truth and instead held that truth involves a belief, facts about the world, other background beliefs, and future consequences of those beliefs. Later in his life James would also come to adopt neutral monism, the view that the ultimatereality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of everything in existence; everything that is not imagination, imaginary. Different Culture, cultures and Academic discipline, academic disciplines conceptualize it in various ways.

Philosophical questions abo ...

is of one kind, and is neither mental nor physical.

John Dewey

John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and Education reform, educational reformer. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.

The overridi ...

(1859–1952), while still engaging in the lofty academic philosophical work of James and Peirce before him, also wrote extensively on political and social matters, and his presence in the public sphere was much greater than his pragmatist predecessors. In addition to being one of the founding members of pragmatism, John Dewey was one of the founders of functional psychology and was a leading figure of the progressive movement in U.S. schooling during the first half of the 20th century.

Dewey argued against the individualism of classical liberalism, asserting that social institutions are not "means for obtaining something for individuals. They are means for creating individuals." He held that individuals are not things that should be accommodated by social institutions, instead, social institutions are prior to and shape the individuals. These social arrangements are a means of creating individuals and promoting individual freedom.

Dewey is well known for his work in the applied philosophy of the philosophy of education. Dewey's philosophy of education is one where children learn by doing. Dewey believed that schooling was unnecessarily long and formal, and that children would be better suited to learn by engaging in real-life activities. For example, in math, students could learn by figuring out proportions in cooking or seeing how long it would take to travel distances with certain modes of transportation.

W. E. B. Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), trained as a historian and sociologist, and described as a pragmatist like his professor William James, pioneered a shift in philosophy away from abstraction and toward engaged social criticism. His contributions in philosophy, like his efforts in other fields, worked toward the goal of equality of colored people. In '' The Souls of Black Folk'', he introduced the concept of '' double consciousness''—the dual self-perception ofAfrican-Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

both through the lens of a racially prejudiced society and as they see themselves for themselves, with their own legitimate feelings and traditions—and in '' Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil'', he introduced the concept of ''second sight''—that this double consciousness of existing both inside the white world and outside of it provides a unique epistemological perspective from which to understand that society.

20th century

Pragmatism, which began in the 19th century in America, by the beginning of the 20th century began to be accompanied by other philosophical schools of thought, and was eventually eclipsed by them, though only temporarily. The 20th century saw the emergence of process philosophy, itself influenced by the scientific world-view andAlbert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

. The middle of the 20th century was witness to the increase in popularity of the philosophy of language

Philosophy of language refers to the philosophical study of the nature of language. It investigates the relationship between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of Meaning (philosophy), me ...

and analytic philosophy in America. Existentialism and phenomenology, while very popular in Europe in the 20th century, never achieved the level of popularity in America as they did in continental Europe.

Rejection of idealism

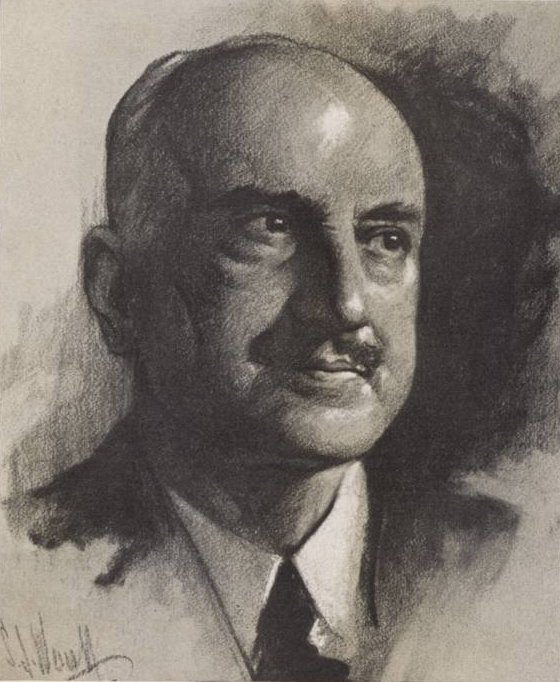

Pragmatism continued its influence into the 20th century, and Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana was one of the leading proponents of pragmatism and realism in this period. He held that

Pragmatism continued its influence into the 20th century, and Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana was one of the leading proponents of pragmatism and realism in this period. He held that idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

was an outright contradiction and rejection of common sense. He held that, if something must be certain in order to be knowledge, then it seems no knowledge may be possible, and the result will be skepticism. According to Santayana, knowledge involved a sort of faith, which he termed "animal faith".

In his book '' Scepticism and Animal Faith'' he asserts that knowledge is not the result of reasoning. Instead, knowledge is what is required in order to act and successfully engage with the world. As a naturalist, Santayana was a harsh critic of epistemological foundationalism. The explanation of events in the natural world is within the realm of science, while the meaning and value of this action should be studied by philosophers. Santayana was accompanied in the intellectual climate of 'common sense' philosophy by the thinkers of the New Realism movement, such as Ralph Barton Perry, who criticized idealism as exhibiting what he called the egocentric predicament.

Santayana was at one point aligned with early 20th-century American proponents of critical realism—such as Roy Wood Sellars—who were also critics of idealism, but Sellars later concluded that Santayana and Charles Augustus Strong were closer to New Realism in their emphasis on veridical perception, whereas Sellars and Arthur O. Lovejoy and James Bissett Pratt were more properly counted among the critical realists who emphasized "the distinction between intuition and denotative characterization". For a later review of some differences between the early 20th-century realists, see: And:

Process philosophy

Process philosophy embraces the Einsteinian world-view, and its main proponents include Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne. The core belief of process philosophy is the claim that events and processes are the principal ontological categories. Whitehead asserted in his book ''The Concept of Nature'' that the things in nature, what he referred to as "concresences" are a conjunction of events that maintain a permanence of character. Process philosophy is Heraclitan in the sense that a fundamental ontological category is change. Charles Hartshorne was also responsible for developing the process philosophy of Whitehead into process theology.Aristotelian philosophy

The University of Chicago became a center of Aristotelian philosophy after president Maynard Hutchins reformed the curriculum according to recommendations by philosopher Mortimer Adler. Adler also influenced Sister Miriam Joseph to teach her college students the medieval Trivium of liberal arts. Adler served as chief editor of the Encyclopædia Britannica, and later founded the Aspen Institute to teach business executives. Richard McKeon also taught Aristotle during the Hutchins era. Many American philosophers contributed to a contemporary "aretaic turn" toward virtue ethics in moral philosophy. Ayn Rand, who claimed Aristotle as her primary philosophical influence, promoted ethical egoism (the praxis of the belief system she called Objectivism) in her novels '' The Fountainhead'' (1943) and '' Atlas Shrugged'' (1957). These two novels gave birth to the Objectivist movement and would influence a small group of students called The Collective, one of whom was a young Alan Greenspan, a self-described libertarian who would becomeChairman of the Federal Reserve

The chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the Federal Reserve, and is the active executive officer of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The chairman presides at meetings of the Board.

...

. Objectivism holds that there is an objective external reality that can be known with reason, that human beings should act in accordance with their own rational self-interest, and that the proper form of economic organization is laissez-faire capitalism."Introducing Objectivism" by Ayn RandRetrieved on September 7, 2009 Some academic philosophers have been highly critical of the quality and intellectual rigor of Rand's work,"The Winnowing of Ayn Rand" by Roderick Long

Retrieved July 10, 2010"The philosophical art of looking out number one" at heraldscotland

Retrieved July 10, 2010 but she remains a popular, albeit controversial, figure within American culture."Ayn Rand" at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Retrieved July 10, 2010

Retrieved July 10, 2010

Analytic philosophy

The middle of the 20th century was the beginning of the dominance ofanalytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy is a broad movement within Western philosophy, especially English-speaking world, anglophone philosophy, focused on analysis as a philosophical method; clarity of prose; rigor in arguments; and making use of formal logic, mat ...

in America. Analytic philosophy, prior to its arrival in America, had begun in Europe with the work of Gottlob Frege

Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege (; ; 8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925) was a German philosopher, logician, and mathematician. He was a mathematics professor at the University of Jena, and is understood by many to be the father of analytic philos ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, G.E. Moore, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

From 1929 to 1947, Witt ...

, and the logical positivists. According to logical positivism, the truths of logic and mathematics are tautologies, and those of science are empirically verifiable. Any other claim, including the claims of ethics, aesthetics, theology, metaphysics, and ontology, are meaningless (this theory is called verificationism). With the rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, many positivists fled Germany to Britain and America, and this helped reinforce the dominance of analytic philosophy in the United States in subsequent years.

W.V.O. Quine, while not a logical positivist, shared their view that philosophy should stand shoulder to shoulder with science in its pursuit of intellectual clarity and understanding of the world. He criticized the logical positivists and the analytic/synthetic distinction of knowledge in his 1951 essay " Two Dogmas of Empiricism" and advocated for his "web of belief," which is a coherentist theory of justification. In Quine's epistemology, since no experiences occur in isolation, there is actually a holistic approach to knowledge where every belief or experience is intertwined with the whole. Quine is also famous for inventing the term "gavagai" as part of his theory of the indeterminacy of translation.

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

, has profoundly influenced analytic philosophy. Kripke was ranked among the top ten most important philosophers of the past 200 years in a poll conducted by Brian Leiter (Leiter Reports: a Philosophy Blog; open access poll) Kripke is best known for four contributions to philosophy: (1) Kripke semantics for modal and related logics, published in several essays beginning while he was still in his teens. (2) His 1970 Princeton lectures Naming and Necessity (published in 1972 and 1980), that significantly restructured the philosophy of language

Philosophy of language refers to the philosophical study of the nature of language. It investigates the relationship between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of Meaning (philosophy), me ...

and, as some have put it, "made metaphysics respectable again". (3) His interpretation of the philosophy of Wittgenstein. (4) His theory of truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

. He has also made important contributions to set theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies Set (mathematics), sets, which can be informally described as collections of objects. Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory – as a branch of mathema ...

(see admissible ordinal and Kripke–Platek set theory)

David Kellogg Lewis, another student of Quine at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

, was ranked as one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century in a poll conducted by Brian Leiter ( open access poll). He is well known for his controversial advocacy of modal realism, the position which holds that there is an infinite number of concrete and causally isolated possible worlds

Possible Worlds may refer to:

* Possible worlds, concept in philosophy

* ''Possible Worlds'' (play), 1990 play by John Mighton

** ''Possible Worlds'' (film), 2000 film by Robert Lepage, based on the play

* Possible Worlds (studio)

* ''Possible ...

, of which ours is one. These possible worlds arise in the field of modal logic.

Thomas Kuhn

Thomas Samuel Kuhn (; July 18, 1922 – June 17, 1996) was an American History and philosophy of science, historian and philosopher of science whose 1962 book ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' was influential in both academic and ...

was an important philosopher and writer who worked extensively in the fields of the history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

and the philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, ...

. He is famous for writing '' The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'', one of the most cited academic works of all time. The book argues that science proceeds through different '' paradigms'' as scientists find new puzzles to solve. There follows a widespread struggle to find answers to questions, and a shift in world views occurs, which is referred to by Kuhn as a '' paradigm shift''. The work is considered a milestone in the sociology of knowledge.

Critical theory

Critical theory—specifically the social theory of theFrankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

—influenced philosophy and culture in the United States beginning in the late 1960s. Critical theory was rooted in the Western European Marxist philosophical tradition and sought philosophy that was "practical" and not merely "theoretical", that would help not only to understand the world but to shape it—generally toward human emancipation and freedom from domination. Its practical and socially transformative orientation was similar to that of earlier American pragmatists such as John Dewey.

Critical theorist Herbert Marcuse, in his '' Eros and Civilization'' (1955), responded to the pessimism of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

's '' Civilization and Its Discontents'' by arguing for the emancipatory power of the imagination and for a "rationality of gratification", a fusion of Logos and Eros, for envisioning a better world. In '' One-Dimensional Man'' (1964), Marcuse argued for a "Great Refusal"—"the protest against that which is", in response to "un-freedoms" and oppressive, conformist social structures. According to Marcuse's student Angela Davis, Marcuse's ''principled utopianism'' articulated the ideals of a generation of activists and revolutionaries around the world. His thought influenced the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

, notably by the Black power movement and student movements of the 1960s. He "was the most influential of the Frankfurt School critical theorists on North American intellectual culture" according to Doug Mann.

American philosophers and writers who have engaged with critical theory include Angela Davis, Edward Said, Martha Nussbaum, bell hooks

Gloria Jean Watkins (September 25, 1952 – December 15, 2021), better known by her pen name bell hooks (stylized in lowercase), was an American author, theorist, educator, and social critic who was a Distinguished Professor in Residence at Be ...

, Cornel West

Cornel Ronald West (born June 2, 1953) is an American philosopher, theologian, political activist, politician, social critic, and public intellectual. West was an independent candidate in the 2024 United States presidential election and is an ou ...

, and Judith Butler. Butler portrays critical theory as a way to rhetorically challenge oppression and inequality, specifically concepts of gender.

Return of political philosophy

In 1971 John Rawls published '' A Theory of Justice'', which puts forth his view of '' justice as fairness'', a version of

In 1971 John Rawls published '' A Theory of Justice'', which puts forth his view of '' justice as fairness'', a version of social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

theory. Rawls employs a conceptual mechanism called the veil of ignorance to outline his idea of the original position. In Rawls' philosophy, the original position is the correlate to the Hobbesian state of nature. While in the original position, persons are said to be behind the veil of ignorance, which makes these persons unaware of their individual characteristics and their place in society, such as their race, religion, wealth, etc. The principles of justice are chosen by rational persons while in this original position. The two principles of justice are the equal liberty principle and the principle that governs the distribution of social and economic inequalities. From this, Rawls argues for a system of distributive justice

Distributive justice concerns the Social justice, socially just Resource allocation, allocation of resources, goods, opportunity in a society. It is concerned with how to allocate resources fairly among members of a society, taking into account fa ...

in accordance with the Difference Principle, which says that all social and economic inequalities must be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged.

Viewing Rawls as promoting excessive government control and rights violations, libertarian Robert Nozick published '' Anarchy, State, and Utopia'' in 1974. The book advocates for a minimal state and defends the liberty of the individual. He argues that the role of government should be limited to "police protection, national defense, and the administration of courts of law, with all other tasks commonly performed by modern governments – education, social insurance, welfare, and so forth – taken over by religious bodies, charities, and other private institutions operating in a free market."

Nozick asserts his view of the entitlement theory of justice, which says that if everyone in society has acquired his or her holdings in accordance with the principles of acquisition, transfer, and rectification, then any pattern of allocation, no matter how unequal the distribution may be, is just. The entitlement theory of justice holds that the "justice of a distribution is indeed determined by certain historical circumstances (contrary to end-state theories), but it has nothing to do with fitting any pattern guaranteeing that those who worked the hardest or are most deserving have the most shares."

Alasdair MacIntyre, born and educated in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, has spent around forty years living and working in the United States. He is responsible for the resurgence of interest in virtue ethics, a moral theory first propounded by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. A prominent Thomist political philosopher, he holds that "modern philosophy and modern life are characterized by the absence of any coherent moral code, and that the vast majority of individuals living in this world lack a meaningful sense of purpose in their lives and also lack any genuine community". He recommends a return to genuine political communities where individuals can properly acquire their virtues.

Outside academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

philosophy, political and social concerns took center stage with the Civil Rights Movement and the writings of Martin Luther King Jr. King was an American Christian minister and activist known for advancing civil rights through nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

and civil disobedience.

Feminism

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades, ending with the feminist sex wars in the early 1980s and being replaced by third-wave feminism in the early 1990s. It occurred ...

, is notable for its impact in philosophy.

The popular mind was taken with Betty Friedan's '' The Feminine Mystique'' (1963). This was accompanied by other feminist philosophers, such as Alicia Ostriker and Adrienne Rich. These philosophers critiqued basic assumptions and values like objectivity and what they believe to be masculine approaches to ethics, such as rights-based political theories. They maintained there is no such thing as a value-neutral inquiry and they sought to analyze the social dimensions of philosophical issues.

Judith Butler's '' Gender Trouble'' (1990), which argued for an understanding of gender

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other tha ...

as socially constructed and performative, helped establish the academic field of gender studies.

Contemporary philosophy

Towards the end of the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are

Towards the end of the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are Hilary Putnam

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (; July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American philosopher, mathematician, computer scientist, and figure in analytic philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. He contributed to the studies of philosophy of ...

and Richard Rorty. Rorty is famous as the author of '' Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature'' and '' Philosophy and Social Hope''. Hilary Putnam is well known for his quasi-empiricism in mathematics, his challenge of the brain in a vat thought experiment

A thought experiment is an imaginary scenario that is meant to elucidate or test an argument or theory. It is often an experiment that would be hard, impossible, or unethical to actually perform. It can also be an abstract hypothetical that is ...

, and his other work in philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

, philosophy of language

Philosophy of language refers to the philosophical study of the nature of language. It investigates the relationship between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of Meaning (philosophy), me ...

, and philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, ...

.

The debates that occur within the philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

have taken center stage. Austrian émigé Herbert Feigl published a summary of the debates, "The 'Mental' and the 'Physical'", in 1958 (with a postscript in 1967). Later, American philosophers such as Hilary Putnam, Donald Davidson, Daniel Dennett, Douglas Hofstadter

Douglas Richard Hofstadter (born 15 February 1945) is an American cognitive and computer scientist whose research includes concepts such as the sense of self in relation to the external world, consciousness, analogy-making, Strange loop, strange ...

, John Searle

John Rogers Searle (; born July 31, 1932) is an American philosopher widely noted for contributions to the philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and social philosophy. He began teaching at UC Berkeley in 1959 and was Willis S. and Mario ...

, as well as Patricia and Paul Churchland continued the discussion of such issues as the nature of mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

and the hard problem of consciousness, a philosophical problem named by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers.

Several mid-20th century American scholars renewed the study of idealism