Amelia Sedley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Vanity Fair'' is a novel by the English author

As Amelia's adored son George grows up, his grandfather Mr Osborne relents towards him (though not towards Amelia) and takes him from his impoverished mother, who knows the rich old man will give him a better start in life than she could manage. After twelve years abroad, both Joseph Sedley and Dobbin return. Dobbin professes his unchanged love to Amelia. Amelia is affectionate, but she cannot forget the memory of her dead husband. Dobbin mediates a reconciliation between Amelia and her father-in-law, who dies soon after. He had amended his will, bequeathing young George half his large fortune and Amelia a generous annuity.

After the death of Mr Osborne, Amelia, Jos, George and Dobbin go to Pumpernickel (

As Amelia's adored son George grows up, his grandfather Mr Osborne relents towards him (though not towards Amelia) and takes him from his impoverished mother, who knows the rich old man will give him a better start in life than she could manage. After twelve years abroad, both Joseph Sedley and Dobbin return. Dobbin professes his unchanged love to Amelia. Amelia is affectionate, but she cannot forget the memory of her dead husband. Dobbin mediates a reconciliation between Amelia and her father-in-law, who dies soon after. He had amended his will, bequeathing young George half his large fortune and Amelia a generous annuity.

After the death of Mr Osborne, Amelia, Jos, George and Dobbin go to Pumpernickel (

Thackeray may have begun working out some of the details of ''Vanity Fair'' as early as 1841 but probably began writing it in late 1844. Like many novels of the time, ''Vanity Fair'' was published as a serial before being sold in book form. It was printed in 20 monthly parts between January 1847 and July 1848 for '' Punch'' by Bradbury & Evans in London. The first three had already been completed before publication, while the others were written after it had begun to sell.

As was standard practice, the last part was a "double number" containing parts 19 and 20. Surviving texts, his notes, and letters show that adjustments were made – e.g., the Battle of Waterloo was delayed twice – but that the broad outline of the story and its principal themes were well established from the beginning of publication.

:No. 1 (January 1847) Ch. 1–4

:No. 2 (February 1847) Ch. 5–7

:No. 3 (March 1847) Ch. 8–11

:No. 4 (April 1847) Ch. 12–14

:No. 5 (May 1847) Ch. 15–18

:No. 6 (June 1847) Ch. 19–22

:No. 7 (July 1847) Ch. 23–25

:No. 8 (August 1847) Ch. 26–29

:No. 9 (September 1847) Ch. 30–32

:No. 10 (October 1847) Ch. 33–35

:No. 11 (November 1847) Ch. 36–38

:No. 12 (December 1847) Ch. 39–42

:No. 13 (January 1848) Ch. 43–46

:No. 14 (February 1848) Ch. 47–50

:No. 15 (March 1848) Ch. 51–53

:No. 16 (April 1848) Ch. 54–56

:No. 17 (May 1848) Ch. 57–60

:No. 18 (June 1848) Ch. 61–63

:No. 19/20 (July 1848) Ch. 64–67

The parts resembled pamphlets and contained the text of several chapters between outer pages of

Thackeray may have begun working out some of the details of ''Vanity Fair'' as early as 1841 but probably began writing it in late 1844. Like many novels of the time, ''Vanity Fair'' was published as a serial before being sold in book form. It was printed in 20 monthly parts between January 1847 and July 1848 for '' Punch'' by Bradbury & Evans in London. The first three had already been completed before publication, while the others were written after it had begun to sell.

As was standard practice, the last part was a "double number" containing parts 19 and 20. Surviving texts, his notes, and letters show that adjustments were made – e.g., the Battle of Waterloo was delayed twice – but that the broad outline of the story and its principal themes were well established from the beginning of publication.

:No. 1 (January 1847) Ch. 1–4

:No. 2 (February 1847) Ch. 5–7

:No. 3 (March 1847) Ch. 8–11

:No. 4 (April 1847) Ch. 12–14

:No. 5 (May 1847) Ch. 15–18

:No. 6 (June 1847) Ch. 19–22

:No. 7 (July 1847) Ch. 23–25

:No. 8 (August 1847) Ch. 26–29

:No. 9 (September 1847) Ch. 30–32

:No. 10 (October 1847) Ch. 33–35

:No. 11 (November 1847) Ch. 36–38

:No. 12 (December 1847) Ch. 39–42

:No. 13 (January 1848) Ch. 43–46

:No. 14 (February 1848) Ch. 47–50

:No. 15 (March 1848) Ch. 51–53

:No. 16 (April 1848) Ch. 54–56

:No. 17 (May 1848) Ch. 57–60

:No. 18 (June 1848) Ch. 61–63

:No. 19/20 (July 1848) Ch. 64–67

The parts resembled pamphlets and contained the text of several chapters between outer pages of

The book has inspired a number of adaptations:

The book has inspired a number of adaptations:

The Victorian Web

– Thackeray's Illustrations to Vanity Fair

– Glossary of foreign words and phrases in Vanity Fair {{Authority control 1848 British novels British novels adapted into films Novels set during the Napoleonic Wars Novels by William Makepeace Thackeray Novels first published in serial form Victorian novels Works originally published in Punch (magazine) British satirical novels British novels adapted into television shows Novels about the Battle of Waterloo Novels set in Waterloo, Belgium Cultural depictions of Napoleon Novels set in the 1810s Novels set in the 1820s Novels set in the 1830s Novels set in Brighton Novels set in London British picaresque novels

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray ( ; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist and illustrator. He is known for his Satire, satirical works, particularly his 1847–1848 novel ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portra ...

, which follows the lives of Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

and Amelia Sedley amid their friends and families during and after the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. It was first published as a 19-volume monthly serial (the last containing Parts 19 ''and'' 20) from 1847 to 1848, carrying the subtitle ''Pen and Pencil Sketches of English Society'', which reflects both its satirisation of early 19th-century British society and the many illustrations drawn by Thackeray to accompany the text. It was published as a single volume in 1848 with the subtitle ''A Novel without a Hero'', reflecting Thackeray's interest in deconstructing his era's conventions regarding literary heroism.. It is sometimes considered the "principal founder" of the Victorian domestic novel.

The story is framed as a puppet play

Puppetry is a form of theatre or performance that involves the manipulation of puppets – inanimate objects, often resembling some type of human or animal figure, that are animated or manipulated by a human called a puppeteer. Such a performan ...

, and the narrator, despite being an authorial voice

In literature, writing style is the manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation. Thus, style is a term that may refer, at one and the same time, to singular aspects of an individual's writing ...

, is somewhat unreliable. The serial was a popular and critical success; the novel is now considered a classic and has inspired several audio, film, and television adaptations. It also inspired the title of the British lifestyle magazine first published in 1868, which became known for its caricatures of famous people of Victorian and Edwardian society. In 2003, ''Vanity Fair'' was listed at No. 122 on the BBC's The Big Read

The Big Read was a survey on books that was carried out by the BBC in the United Kingdom in 2003, when over three-quarters of a million votes were received from the British public to find the nation's best-loved novel. The year-long survey was th ...

poll of the UK's best-loved books.

Title

The book's title comes fromJohn Bunyan

John Bunyan (; 1628 – 31 August 1688) was an English writer and preacher. He is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress'', which also became an influential literary model. In addition to ''The Pilgrim' ...

's ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is commonly regarded as one of the most significant works of Protestant devotional literature and of wider early moder ...

'', a Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

first published in 1678. In that work, "Vanity Fair" refers to a stop along the pilgrim's route: a never-ending fair held in a town called Vanity, which represents man's sinful attachment to worldly things. Thackeray does not mention Bunyan in the novel or in his surviving letters about it, where he describes himself dealing with "living without God in the world", but he did expect the reference to be understood by his audience, as shown in an 1851 ''Times

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events, and a fundamental quantity of measuring systems.

Time or times may also refer to:

Temporal measurement

* Time in physics, defined by its measurement

* Time standard, civil time specificat ...

'' article likely written by Thackeray himself.

Robert Bell—whose friendship later became so great that he was buried near Thackeray at Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of North Kensington in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in P ...

—complained that the novel could have used "more light and air" to make it "more agreeable and healthy". Thackeray rebutted this with Evangelist's words as the pilgrims entered Bunyan's Vanity Fair: "The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; who can know it?"

From its appearance in Bunyan, "Vanity Fair" or a "vanity-fair" was also in general use for "the world" in a range of connotations from the blandly descriptive to the wearily dismissive to the condemning. By the 18th century, it was generally taken as a playground and, in the first half of the 19th century, more specifically the playground of the idle and undeserving rich. All of these senses appear in Thackeray's work. The name " Vanity Fair" has also been used for at least 5 periodicals.

Plot summary

The story is framed by its preface. and coda as apuppet show

Puppetry is a form of theatre or performance that involves the manipulation of puppets – inanimate objects, often resembling some type of human or animal figure, that are animated or manipulated by a human called a puppeteer. Such a performan ...

taking place at a fair; the cover illustration of the serial installments was not of the characters but of a troupe of comic actors at Speakers' Corner

A Speakers' Corner is an area where free speech public speaking, open-air public speaking, debate, and discussion are allowed. The original and best known is in the north-east corner of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park in London, England. Histor ...

in Hyde Park. The narrator, variously a show manager or writer, appears at times within the work itself and is somewhat unreliable,. repeating a tale of gossip at second or third hand.

In London in 1814, Rebecca Sharp ("Becky"), daughter of an art teacher and a French dancer, is a strong-willed, cunning, moneyless young woman determined to make her way in society. After leaving school, Becky stays with her friend Amelia Sedley ("Emmy"), who is a good-natured, simple-minded young girl, of a wealthy London family. There, Becky meets the dashing and self-obsessed Captain George Osborne (Amelia's betrothed) and Amelia's brother Joseph ("Jos") Sedley, a clumsy and vainglorious but rich civil servant home from the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

. Hoping to marry Sedley, the richest young man she has met, Becky entices him, but she fails. George Osborne's friend Captain William Dobbin loves Amelia, but only wishes her happiness, which is centred on George.

Becky Sharp says farewell to the Sedley family and enters the service of the crude and profligate baronet Sir Pitt Crawley, who has engaged her as a governess to his daughters. Her behaviour at Sir Pitt's house gains his favour, and after the premature death of his second wife, he proposes marriage to her. However, he finds that Becky has secretly married his second son, Captain Rawdon Crawley, a plot orchestrated by Bute Crawley to ensure that Sir Pitt's elder half sister, the spinster Miss Crawley, who is very rich (having inherited her mother's fortune) disinherits Rawdon; and the whole Crawley family compete for her favour so she will bequeath them her wealth. Initially her favourite is Rawdon Crawley, but his marriage with Becky enrages her. First she favours the family of Sir Pitt's brother, but when she dies, she leaves her money to Sir Pitt's eldest son, also called Pitt.

News arrives that Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

has escaped from Elba, and as a result the stockmarket becomes jittery, causing Amelia's stockbroker father, John Sedley, to become bankrupt. George's rich father forbids George to marry Amelia, who is now poor. Dobbin persuades George to marry Amelia, and George is consequently disinherited. George Osborne, William Dobbin and Rawdon Crawley are deployed to Brussels, accompanied by Amelia and Becky, and Amelia's brother, Jos.

George is embarrassed by the vulgarity of Mrs. Major O'Dowd, the wife of the head of the regiment. The newly wedded Osborne is already growing tired of Amelia, and he becomes increasingly attracted to Becky, which makes Amelia jealous and unhappy. He is also losing money to Rawdon at cards and billiards. At a ball in Brussels, George gives Becky a note inviting her to run away with him (although this fact is not revealed until the end of the book). But then the army have marching orders to the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

, and George spends a tender night with Amelia and leaves.

The noise of battle horrifies Amelia, and she is comforted by the brisk but kind Mrs. O'Dowd. Becky is indifferent and makes plans for whatever the outcome (for example, if Napoleon wins, she would aim to become the mistress of one of his Marshals). She also makes a profit selling her carriage and horses at inflated prices to Jos, who is seeking to flee Brussels.

George Osborne is killed at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

, while Dobbin and Rawdon survive the battle. Amelia bears him a posthumous son, who carries on the name George. She returns to live in genteel poverty

Genteel poverty is a state of poverty marked by one's connection or affectation towards a higher ("wiktionary:genteel, genteel") social class. Those in genteel poverty are often people, possibly Imperial, royal and noble ranks, titled, who have fa ...

with her parents, spending her life in memory of her husband and care of her son. Dobbin pays for a small annuity for Amelia and expresses his love for her by small kindnesses toward her and her son. She is too much in love with her husband's memory to return Dobbin's love. Saddened, he goes with his regiment to India for many years.

Becky also gives birth to a son, named Rawdon after his father. Becky is a cold, distant mother, although Rawdon loves his son. Becky continues her ascent first in post-war Paris and then in London where she is patronised by the rich and powerful Marquis of Steyne. She is eventually presented at court to the Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness) or ab ...

and charms him further at a game of " acting charades" where she plays the roles of Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra (, ; , ), in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Sparta. In Aeschylus' ''Oresteia'', she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan p ...

and Philomela

Philomela () or Philomel (; , ; ) is a minor figure in Greek mythology who is frequently invoked as a direct and figurative symbol in literary and artistic works in the Western canon.

Family

Philomela was the younger of two daughters of P ...

. The elderly Sir Pitt Crawley dies and is succeeded by his son Pitt, who had married Lady Jane Sheepshanks, Lord Southdown's third daughter. Becky is on good terms with Pitt and Jane originally, but Jane is disgusted by Becky's attitude to her son and jealous of Becky's relationship with Pitt.

At the summit of their social success, Rawdon is arrested for debt, possibly at Becky's connivance. The financial success of the Crawleys had been a topic of gossip; in fact they were living on credit even when it ruined those who trusted them, such as their landlord, an old servant of the Crawley family. The Marquis of Steyne had given Becky money, jewels, and other gifts but Becky does not use them for expenses or to free her husband. Instead, Rawdon's letter to his brother is received by Lady Jane, who pays the £170 that prompted his imprisonment.

He returns home to find Becky singing to Steyne and strikes him down on the assumption—despite her protestations of innocence—that they are having an affair. Steyne is indignant, having assumed the £1000 he had just given Becky was part of an arrangement with her husband. Rawdon finds Becky's hidden bank records and leaves her, expecting Steyne to challenge him to a duel. Instead Steyne arranges for Rawdon to be made Governor of Coventry Island, a pestilential and disease-ridden location. Becky, having lost both husband and credibility, leaves England and wanders the continent, leaving her son in the care of Pitt and Lady Jane.

As Amelia's adored son George grows up, his grandfather Mr Osborne relents towards him (though not towards Amelia) and takes him from his impoverished mother, who knows the rich old man will give him a better start in life than she could manage. After twelve years abroad, both Joseph Sedley and Dobbin return. Dobbin professes his unchanged love to Amelia. Amelia is affectionate, but she cannot forget the memory of her dead husband. Dobbin mediates a reconciliation between Amelia and her father-in-law, who dies soon after. He had amended his will, bequeathing young George half his large fortune and Amelia a generous annuity.

After the death of Mr Osborne, Amelia, Jos, George and Dobbin go to Pumpernickel (

As Amelia's adored son George grows up, his grandfather Mr Osborne relents towards him (though not towards Amelia) and takes him from his impoverished mother, who knows the rich old man will give him a better start in life than she could manage. After twelve years abroad, both Joseph Sedley and Dobbin return. Dobbin professes his unchanged love to Amelia. Amelia is affectionate, but she cannot forget the memory of her dead husband. Dobbin mediates a reconciliation between Amelia and her father-in-law, who dies soon after. He had amended his will, bequeathing young George half his large fortune and Amelia a generous annuity.

After the death of Mr Osborne, Amelia, Jos, George and Dobbin go to Pumpernickel (Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

),. where they encounter the destitute Becky. Becky has fallen in life. She lives among card sharps and con artists, drinking heavily and gambling. Becky enchants Jos Sedley all over again, and Amelia is persuaded to let Becky join them. Dobbin forbids this, and reminds Amelia of her jealousy of Becky with her husband. Amelia feels that this dishonours the memory of her dead and revered husband, and this leads to a complete breach between her and Dobbin. Dobbin leaves the group and rejoins his regiment, while Becky remains with the group.

However, Becky has decided that Amelia should marry Dobbin, even though Becky knows Dobbin is her enemy. Becky shows Amelia George's note, kept all this time from the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, and Amelia finally realises that George was not the perfect man she always thought, and that she has rejected a better man, Dobbin. Amelia and Dobbin are reconciled and return to England. Becky and Jos stay in Europe. Jos dies, possibly suspiciously, after signing a portion of his money to Becky as life insurance, thereby setting her up with an income. She returns to England, and manages a respectable life, although all her previous friends refuse to acknowledge her.

Characters

Emmy Sedley (Amelia)

Amelia, called Emmy, is good-natured but passive and naïve. Pretty rather than beautiful, she has a snub nose and round, rosy cheeks. She is well-liked by men, and women when few men are around, as was the case when she was at school. She begins the work as its heroine ("selected for the very reason that she was the best-natured of all") and marries the dashing George Osborne against his father's wishes, but the narrator is soon forced to admit "she wasn't a heroine" after all as she remains soppily devoted to him despite his neglect of her and his flirtation with Becky. After George dies in theBattle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

, she brings up little George alone while living with her parents. She is completely dominated by her increasingly peevish mother and her spendthrift father, who, to finance one of his failing investment schemes, sells the annuity Jos had provided. Amelia becomes obsessed with her son and the memory of her husband. She ignores William Dobbin, who courts her for years and treats him shabbily until he leaves. Only when Becky shows her George's letter to her, indicating his unfaithfulness, can Amelia move on. She then marries Dobbin.

In a letter to his close friend Jane Octavia Brookfield while the book was being written, Thackeray confided that "You know you are only a piece of Amelia, my mother is another half, my poor little wife ''y est pour beaucoup''". Within the work, her character is compared and connected to Iphigenia

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia (; , ) was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

In the story, Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting and killing one of Artem ...

, although two of the references extend the allusion to all daughters in all drawing rooms as potential Iphigenias waiting to be sacrificed by their families.

Becky Sharp (Rebecca)

Rebecca Sharp, called Becky, is Amelia's opposite: an intelligent, conniving young woman with a gift for satire. She is described as a short, sandy-haired girl who has green eyes and a great deal of wit. Becky is born to a French opera dancer mother and an art teacher and artist father Francis. Fluent in both French and English, Becky has a beautiful singing voice, plays the piano, and shows great talent as an actress. Without a mother to guide her into marriage, Becky resolves that "I must be my own Mamma". She thereafter appears to be completely amoral and without conscience and has been called the work's "anti-heroine

An antihero (sometimes spelled as anti-hero or two words anti hero) or anti-heroine is a character in a narrative (in literature, film, TV, etc.) who may lack some conventional heroic qualities and attributes, such as idealism and morality. Al ...

". She does not seem to have the ability to get attached to other people, and lies easily and intelligently to get her way. She is extremely manipulative and, after the first few chapters and her failure to attract Jos Sedley, is not shown as being particularly sincere.

Never having known financial or social security even as a child, Becky desires it above all things. Nearly everything she does is with the intention of securing a stable position for herself, or herself and her husband after she and Rawdon are married. She advances Rawdon's interests tirelessly, flirting with men such as General Tufto and the Marquis of Steyne to get him promoted. She also uses her feminine wiles to distract men at card parties while Rawdon cheats them blind.

Marrying Rawdon Crawley in secret was a mistake, as was running off instead of begging Miss Crawley's forgiveness. She also fails to manipulate Miss Crawley through Rawdon so as to obtain an inheritance. Although Becky manipulates men very easily, she is less successful with women. She is utterly hostile to Lady Bareacres, dismissive of Mrs. O'Dowd, and Lady Jane, although initially friendly, eventually distrusts and dislikes her.

The exceptions to this trend are (at least initially) Miss Crawley, her companion

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

Miss Briggs, and her school friend Amelia; the latter is the recipient of more-or-less the only kindnesses Becky expresses in the work, persuading her to marry Dobbin in light of what Becky comes to appreciate to be his good qualities and protecting Amelia from two ruffians vying for her attentions. This comparative loyalty to Amelia stems from Becky having no other friends at school, and Amelia having "by a thousand kind words and offices, overcome... (Becky's) hostility"; 'The gentle tender-hearted Amelia Sedley was the only person to whom she could attach herself in the least; and who could help attaching herself to Amelia?'

Beginning with her determination to be her "own Mamma", Becky begins to assume the role of Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra (, ; , ), in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Sparta. In Aeschylus' ''Oresteia'', she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan p ...

. Becky and her necklace from Steyne also allude to the fallen Eriphyle

Eriphyle (; ) was a figure in Greek mythology who, in exchange for the Necklace of Harmonia (also called the Necklace of Eriphyle) given to her by Polynices, persuaded her husband Amphiaraus to join the doomed expedition of the Seven against Theb ...

in Racine's retelling

Retelling, in media studies and literary studies, is the production of a derivative work that is substantially based on an earlier work but that presents the story differently. In literature

Retelling, in literature, refashions a story in a way ...

of ''Iphigenia at Aulis

''Iphigenia in Aulis'' or ''Iphigenia at Aulis'' (; variously translated, including the Latin ''Iphigenia in Aulide'') is the last of the extant works by the playwright Euripides. Written between 408, after ''Orestes'', and 406 BC, the year of Eu ...

'', where she doubles and rescues Iphigenia. In lesser contexts, Becky also appears as Arachne

Arachne (; from , cognate with Latin ) is the protagonist of a tale in classical mythology known primarily from the version told by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE–17 CE). In Book Six of his epic poem ''Metamorphoses'', Ovid recounts how ...

to Miss Pinkerton's Minerva

Minerva (; ; ) is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. She is also a goddess of warfare, though with a focus on strategic warfare, rather than the violence of gods such as Mars. Be ...

and as a variety of classical figures in the works' illustrations.

George Osborne

George Osborne, his father (a merchant, of considerably superior social status to Dobbin's grocer father, albeit self made, and ironically a mere corporal in the City Light Horse regiment of which Dobbin senior, by this time an alderman and a knight, is colonel), and his two sisters are close to the Sedley family until Mr. Sedley (the father of Jos and Amelia, and George Osborne's godfather, from whom the latter takes his middle name of 'Sedley') goes bankrupt following some ill-advised speculation. Since George and Amelia were raised in close company and were childhood sweethearts, George defies his father to marry Amelia. Before father and son can be reconciled, George is killed at the battle of Waterloo, leaving the pregnant Amelia to carry on as well as she can. Raised to be a selfish, vain, profligate spender, handsome and self-obsessed, George squanders the last of the money he receives from his father and sets nothing aside to help support Amelia. After marrying Amelia, he finds after a couple of weeks that he is bored. He flirts with Becky quite seriously and is reconciled to Amelia only a short time before he is killed in battle.William Dobbin

The best friend of George Osborne, Captain William Dobbin is tall, ungainly, and not particularly handsome. He is a few years older than George but has been friends with him since his schooldays, even though Dobbin's father is a fig-merchant (Dobbin & Rudge, grocers and oilmen, Thames Street, London - he is later an alderman and colonel of the City Light Horse regiment, and knighted) and the Osbornes belong to the genteel class and have become independently wealthy. He defends George and is blind to his faults in many ways, although he tries to force George to do the right thing. He pushes George to keep his promise to marry Amelia even though Dobbin is in love with Amelia himself. After George is killed, Dobbin puts together an annuity to help support Amelia, ostensibly with the help of George's fellow officers. Later, Major and Lieutenant Colonel Dobbin discreetly does what he can to help support Amelia and her son George. He allows Amelia to continue with her obsession over George and does not correct her erroneous beliefs about him. He hangs about for years, either pining away over her while serving in India or waiting on her in person, allowing her to take advantage of his good nature. After Amelia finally chooses Becky's friendship over his during their stay in Germany, Dobbin leaves in disgust. He returns when Amelia writes to him and admits her feelings for him, marries her (despite having lost much of his passion for her), and has a daughter whom he loves deeply.Rawdon Crawley

Rawdon, the younger of the two Crawley sons, is an empty-headed cavalry officer who is his wealthy aunt's favourite until he marries Becky Sharp, who is of a far lower class. He permanently alienates his aunt, who leaves her estate to Rawdon's elder brother Sir Pitt instead. Sir Pitt has by this time inherited their father's estate, leaving Rawdon destitute. The well-meaning Rawdon does have a few talents in life, most of them having to do with gambling and duelling. He is very good at cards and billiards, and although he does not always win he is able to earn cash by betting against less talented gamblers. He is heavily indebted throughout most of the book, not so much for his own expenses as for Becky's. Not particularly talented as a military officer, he is content to let Becky manage his career. Although Rawdon knows Becky is attractive to men, he believes her reputation is spotless even though she is widely suspected of romantic intrigue with General Tufto and other powerful men. Nobody dares to suggest otherwise to Rawdon because of his temper and his reputation for duelling. Yet other people, particularly the Marquis of Steyne, find it impossible to believe that Crawley is unaware of Becky's tricks. Steyne in particular believes Rawdon is fully aware Becky is prostituting herself, and believes Rawdon is going along with the charade in the hope of financial gain. After Rawdon finds out the truth and leaves Becky for an assignment overseas, he leaves his son to be brought up by his brother Sir Pitt and his wife Lady Jane. While overseas, Rawdon dies of yellow fever.Pitt Crawley

Rawdon Crawley's elder brother inherits the Crawley estate from his father, the boorish and vulgar Sir Pitt, and also inherits the estate of his wealthy aunt, Miss Crawley, after she disinherits Rawdon. Pitt is very religious and has political aspirations, although not many people appreciate his intelligence or wisdom because there's not much there to appreciate. Somewhat pedantic and conservative, Pitt does nothing to help Rawdon or Becky even when they fall on hard times. This is chiefly due to the influence of his wife, Lady Jane, who dislikes Becky because of her callous treatment of her son, and also because Becky repaid Lady Jane's earlier kindness by patronising her and flirting with Sir Pitt.Miss Matilda Crawley

The elderly Miss Crawley is everyone's favourite wealthy aunt. Sir Pitt and Rawdon both dote on her, although Rawdon is her favourite nephew and sole heir until he marries Becky. While Miss Crawley likes Becky and keeps her around to entertain her with sarcasm and wit, and while she loves scandal and particularly stories of unwise marriage, she does not want scandal or unwise marriage in her family. A substantial part of the early section of the book deals with the efforts the Crawleys make to kowtow to Miss Crawley in the hope of receiving a big inheritance. Thackeray spent time in Paris with his maternal grandmother Harriet Becher, and Miss Crawley's character is said to be based on her.Joseph Sedley

Amelia's older brother, Joseph "Jos" Sedley, is a "nabob

A nabob is a conspicuously wealthy man deriving his fortune in the east, especially in India during the 18th century with the privately held East India Company.

Etymology

''Nabob'' is an Anglo-Indian term that came to English from Urdu, poss ...

", who made a respectable fortune as a collector in India. Obese and self-important but very shy and insecure, he is attracted to Becky Sharp but circumstances prevent him from proposing. He never marries, but when he meets Becky again he is easily manipulated into falling in love with her. Jos is not a courageous or intelligent man, displaying his cowardice at the Battle of Waterloo by trying to flee and purchasing both of Becky's overpriced horses. Becky ensnares him again near the end of the book and, it is hinted, murders him for his life insurance.

Publication history

Thackeray may have begun working out some of the details of ''Vanity Fair'' as early as 1841 but probably began writing it in late 1844. Like many novels of the time, ''Vanity Fair'' was published as a serial before being sold in book form. It was printed in 20 monthly parts between January 1847 and July 1848 for '' Punch'' by Bradbury & Evans in London. The first three had already been completed before publication, while the others were written after it had begun to sell.

As was standard practice, the last part was a "double number" containing parts 19 and 20. Surviving texts, his notes, and letters show that adjustments were made – e.g., the Battle of Waterloo was delayed twice – but that the broad outline of the story and its principal themes were well established from the beginning of publication.

:No. 1 (January 1847) Ch. 1–4

:No. 2 (February 1847) Ch. 5–7

:No. 3 (March 1847) Ch. 8–11

:No. 4 (April 1847) Ch. 12–14

:No. 5 (May 1847) Ch. 15–18

:No. 6 (June 1847) Ch. 19–22

:No. 7 (July 1847) Ch. 23–25

:No. 8 (August 1847) Ch. 26–29

:No. 9 (September 1847) Ch. 30–32

:No. 10 (October 1847) Ch. 33–35

:No. 11 (November 1847) Ch. 36–38

:No. 12 (December 1847) Ch. 39–42

:No. 13 (January 1848) Ch. 43–46

:No. 14 (February 1848) Ch. 47–50

:No. 15 (March 1848) Ch. 51–53

:No. 16 (April 1848) Ch. 54–56

:No. 17 (May 1848) Ch. 57–60

:No. 18 (June 1848) Ch. 61–63

:No. 19/20 (July 1848) Ch. 64–67

The parts resembled pamphlets and contained the text of several chapters between outer pages of

Thackeray may have begun working out some of the details of ''Vanity Fair'' as early as 1841 but probably began writing it in late 1844. Like many novels of the time, ''Vanity Fair'' was published as a serial before being sold in book form. It was printed in 20 monthly parts between January 1847 and July 1848 for '' Punch'' by Bradbury & Evans in London. The first three had already been completed before publication, while the others were written after it had begun to sell.

As was standard practice, the last part was a "double number" containing parts 19 and 20. Surviving texts, his notes, and letters show that adjustments were made – e.g., the Battle of Waterloo was delayed twice – but that the broad outline of the story and its principal themes were well established from the beginning of publication.

:No. 1 (January 1847) Ch. 1–4

:No. 2 (February 1847) Ch. 5–7

:No. 3 (March 1847) Ch. 8–11

:No. 4 (April 1847) Ch. 12–14

:No. 5 (May 1847) Ch. 15–18

:No. 6 (June 1847) Ch. 19–22

:No. 7 (July 1847) Ch. 23–25

:No. 8 (August 1847) Ch. 26–29

:No. 9 (September 1847) Ch. 30–32

:No. 10 (October 1847) Ch. 33–35

:No. 11 (November 1847) Ch. 36–38

:No. 12 (December 1847) Ch. 39–42

:No. 13 (January 1848) Ch. 43–46

:No. 14 (February 1848) Ch. 47–50

:No. 15 (March 1848) Ch. 51–53

:No. 16 (April 1848) Ch. 54–56

:No. 17 (May 1848) Ch. 57–60

:No. 18 (June 1848) Ch. 61–63

:No. 19/20 (July 1848) Ch. 64–67

The parts resembled pamphlets and contained the text of several chapters between outer pages of steel engraving

Steel engraving is a technique for printing illustrations on paper using steel printing plates instead of copper, the harder metal allowing a much longer print run before the image quality deteriorates. It has been rarely used in artistic printmak ...

s and advertising. Wood engraving

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, in which an artist works an image into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and prints using relatively l ...

s, which could be set along with normal moveable type, appeared within the text. The same engraved illustration appeared on the canary-yellow cover of each monthly part; this colour became Thackeray's signature, as a light blue-green was Dickens's, allowing passers-by to notice a new Thackeray number in a bookstall from a distance.

''Vanity Fair'' was the first work that Thackeray published under his own name and was extremely well received at the time. After the conclusion of its serial publication, it was printed as a bound volume by Bradbury & Evans in 1848 and was quickly picked up by other London printers as well. As a collected work, the novels bore the subtitle ''A Novel without a Hero''. By the end of 1859, royalties

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset or ...

on ''Vanity Fair'' had only given Thackeray about £2000, a third of his take from '' The Virginians'', but was responsible for his still more lucrative lecture tours in Britain and the United States..

From his first draft and following publication, Thackeray occasionally revised his allusions to make them more accessible for his readers. In Chapter 5, an original "Prince Whadyecallem" became "Prince Ahmed" by the 1853 edition. In Chapter 13, a passage about the filicidal Biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

figure Jephthah

Jephthah (pronounced ; , ''Yiftāḥ'') appears in the Book of Judges as a judge who presided over Israel for a period of six years (). According to Judges, he lived in Gilead. His father's name is also given as Gilead, and, as his mother is de ...

was removed, although references to Iphigenia

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia (; , ) was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

In the story, Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting and killing one of Artem ...

remained important. In Chapter 56, Thackeray originally confused Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

– the boy whose mother Hannah had given him up when called to by God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

– with Eli

Eli most commonly refers to:

* Eli (name), a given name, nickname and surname

* Eli (biblical figure)

Eli or ELI may also refer to:

Film

* ''Eli'' (2015 film), a Tamil film

* ''Eli'' (2019 film), an American horror film

Music

* ''Eli'' (Jan ...

, the old priest to whose care he was entrusted; this mistake was not corrected until the 1889 edition, after Thackeray's death.

The serials had been subtitled ''Pen and Pencil Sketches of English Society'' and both they and the early bound versions featured Thackeray's own illustrations. These sometimes provided symbolically-freighted images, such as one of the female characters being portrayed as a man-eating mermaid

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Mermaids are ...

. In at least one case, a major plot point is provided through an image and its caption. Although the text makes it clear that other characters suspect Becky Sharp to have murdered her second husband, there is nothing definitive in the text itself. However, an image reveals her overhearing Jos pleading with Dobbin while clutching a small white object in her hand. The caption that this is ''Becky's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra (, ; , ), in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the half-sister of Helen of Sparta. In Aeschylus' ''Oresteia'', she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan p ...

'' clarifies that she did indeed murder him for the insurance money, likely through laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Reddish-br ...

or another poison..

"The final three illustrations of ''Vanity Fair'' are tableaux that insinuate visually what the narrator is unwilling to articulate: that Becky... has actually been substantially rewarded – by society – for her crimes." One of the Thackeray's plates for the 11th issue of ''Vanity Fair'' was suppressed from publication by threat of prosecution for libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

, so great was the resemblance of its depiction of Lord Steyne to the Marquis of Hertford

The titles of Earl of Hertford and Marquess of Hertford have been created several times in the peerages of England and Great Britain.

The third Earldom of Hertford was created in 1559 for Edward Seymour, who was simultaneously created Baron Be ...

. Despite their relevance, most modern editions either do not reproduce all the illustrations or do so with poor detail.

* .

* , reprinted 1925.

* , without illustration.

* .

* , reprinted 1898.

* , reprinted 1886.

* .

* .

* , in four editions.

*

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* .

* , reprinted 1995.

* .

* , reprinted 2008.

* .

* , reprinted 2003, 2004, & 2008.

* .

* .

* .

* . &

Reception and criticism

Contemporaneous reception

The style is highly indebted toHenry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

. Thackeray meant the book to be not only entertaining but also instructive, an intention demonstrated through the book's narration and through Thackeray's private correspondence. A letter to his editor at '' Punch'' expressed his belief that "our profession... is as serious as the parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term d ...

's own".. He considered it his own coming-of-age as a writer and greatest work..

Critics hailed the work as a literary treasure before the last part of the serial was published. In her correspondence, Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Nicholls (; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855), commonly known as Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ), was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë family, Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novel ...

was effusive regarding his illustrations as well: "You will not easily find a second Thackeray. How he can render, with a few black lines and dots, shades of expression, so fine, so real; traits of character so minute, so subtle, so difficult to seize and fix, I cannot tell—I can only wonder and admire... If Truth were again a goddess, Thackeray should be her high priest."

The early reviewers took the debt to Bunyan as self-evident and compared Becky with Pilgrim and Thackeray with Faithful. Although they were superlative in their praise, some expressed disappointment at the unremittingly dark portrayal of human nature, fearing Thackeray had taken his dismal metaphor too far. In response to these critics, Thackeray explained that he saw people for the most part as "abominably foolish and selfish".

The unhappy ending was intended to inspire readers to look inward at their own shortcomings. Other critics took notice of or exception to the social subversion in the work; in his correspondence, Thackeray stated his criticism was not reserved to the upper class: "My object is to make every body engaged, engaged in the pursuit of Vanity Fair and I must carry my story through in this dreary minor key, with only occasional hints here and there of better things—of better things which it does not become me to preach"..

Analysis

The novel is considered a classic of English literature, though some critics claim that it has structural problems; Thackeray sometimes lost track of the huge scope of his work, mixing up characters' names and minor plot details. The number of allusions and references it contains can make it difficult for modern readers to follow. The subtitle, ''A Novel without a Hero'', refers to the characters all being flawed to a greater or lesser degree; even the most sympathetic have weaknesses, for example Captain Dobbin, who is prone tovanity

Vanity is the excessive belief in one's own abilities or attractiveness compared to others. Prior to the 14th century, it did not have such narcissistic undertones, and merely meant ''futility''. The related term vainglory is now often seen as ...

and melancholy. The human weaknesses Thackeray illustrates are mostly to do with greed

Greed (or avarice, ) is an insatiable desire for material gain (be it food, money, land, or animate/inanimate possessions) or social value, such as status or power.

Nature of greed

The initial motivation for (or purpose of) greed and a ...

, idleness

Idleness is a lack of motion or energy. In describing a person, ''idle'' suggests having no labor: "idly passing the day".

In physics, an idle machine exerts no transfer of energy. When a vehicle is not in motion, an idling engine does no use ...

, and snob

''Snob'' is a pejorative term for a person who feels superior due to their social class, education level, or social status in general;De Botton, A. (2004), ''Status Anxiety''. London: Hamish Hamilton it is sometimes used especially when they pr ...

bery, and the scheming, deceit

Deception is the act of convincing of one or many recipients of untrue information. The person creating the deception knows it to be false while the receiver of the information does not. It is often done for personal gain or advantage.

Deceit ...

and hypocrisy

Hypocrisy is the practice of feigning to be what one is not or to believe what one does not. The word "hypocrisy" entered the English language ''c.'' 1200 with the meaning "the sin of pretending to virtue or goodness". Today, "hypocrisy" ofte ...

which mask them. None of the characters is wholly evil, although Becky's manipulative, amoral tendencies make her come pretty close. However, even Becky, who is amoral and cunning, is thrown on her own resources by poverty and its stigma. (She is the orphaned daughter of a poor artist and an opera dancer.) Thackeray's tendency to highlight faults in all of his characters displays his desire for a greater level of realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*American Realism

*Classical Realism

*Liter ...

in his fiction compared to the rather unlikely or idealised people in many contemporary novels.

The novel is a satire of society as a whole, characterised by hypocrisy and opportunism

300px, ''Opportunity Seized, Opportunity Missed'', engraving by Theodoor Galle, 1605

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances — with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opport ...

, but it is not necessarily a reforming novel; there is no clear suggestion that social or political changes or greater piety and moral reformism could improve the nature of society. It thus paints a fairly bleak view of the human condition. This bleak portrait is continued with Thackeray's own role as an omniscient narrator

Narration is the use of a written or spoken commentary to convey a story to an audience. Narration is conveyed by a narrator: a specific person, or unspecified literary voice, developed by the creator of the story to deliver information to the ...

, one of the writers best known for using the technique. He continually offers asides about his characters and compares them to actors and puppets, but his cheek goes even as far as his readers, accusing all who may be interested in such "Vanity Fairs" as being either "of a lazy, or a benevolent, or a sarcastic mood". As Lord David Cecil

Lord Edward Christian David Gascoyne-Cecil, CH (9 April 1902 – 1 January 1986) was a British biographer, historian, and scholar. He held the style of "Lord" by courtesy as a younger son of a marquess.

Early life and studies

David Cecil was ...

remarked, "Thackeray liked people, and for the most part he thought them well-intentioned. But he also saw very clearly that they were all in some degree weak and vain, self-absorbed and self-deceived." Amelia begins as a warm-hearted and friendly girl, though sentimental and naive, but by the story's end she is portrayed as vacuous and shallow. Dobbin appears first as loyal and magnanimous, if unaware of his own worth; by the end of the story he is presented as a tragic fool, a prisoner of his own sense of duty who knows he is wasting his gifts on Amelia but is unable to live without her. The novel's increasingly grim outlook can take readers aback, as characters whom the reader at first holds in sympathy are shown to be unworthy of such regard.

The work is often compared to the other great historical novel of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

's ''War and Peace

''War and Peace'' (; pre-reform Russian: ; ) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. Set during the Napoleonic Wars, the work comprises both a fictional narrative and chapters in which Tolstoy discusses history and philosophy. An ...

''. While Tolstoy's work has a greater emphasis on the historical detail and the effect the war has upon his protagonists, Thackeray instead uses the conflict as a backdrop to the lives of his characters. The momentous events on the continent do not always have an equally important influence on the behaviours of Thackeray's characters. Rather their faults tend to compound over time. This is in contrast to the redemptive power the conflict has on the characters in ''War and Peace''. For Thackeray, the Napoleonic Wars as a whole can be thought of as one more of the vanities expressed in the title.

A common critical topic is to address various objects in the book and the characters' relationships with them, such as Rebecca's diamonds or the piano Amelia values when she thinks it came from George and dismisses upon learning that Dobbin provided it. Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

and similar schools of criticism that go farther and see Thackeray condemning consumerism

Consumerism is a socio-cultural and economic phenomenon that is typical of industrialized societies. It is characterized by the continuous acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing quantities. In contemporary consumer society, the ...

and capitalism. However, while Thackeray is pointed in his criticism of the commodification of women in the marriage market, his variations on Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes ( ) is one of the Ketuvim ('Writings') of the Hebrew Bible and part of the Wisdom literature of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly used in English is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew word ...

's " all is vanity" are often interpreted as personal rather than institutional. He also has broad sympathy with a measure of comfort and financial and physical "snugness". At one point, the narrator even makes a "robust defense of his lunch": "It is all vanity to be sure: but who will not own to liking a little of it? I should like to know what well-constituted mind, merely because it is transitory, dislikes roast-beef?"

Despite the clear implications of Thackeray's illustration on the topic, John Sutherland has argued against Becky having murdered Jos on the basis of Thackeray's criticism of the "Newgate novel The Newgate novels (or Old Bailey novels) were novels published in England from the late 1820s until the 1840s that glamorised the lives of the criminals they portrayed. Most drew their inspiration from the '' Newgate Calendar'', a biography of famo ...

s" of Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton (; 25 May 1803 – 18 January 1873) was an English writer and politician. He served as a Whig member of Parliament from 1831 to 1841 and a Conservative from 1851 to 1866. He was Secr ...

and other authors of Victorian crime fiction. Although what Thackeray principally objected to was glorification of a criminal's deeds, his intent may have been to entrap the Victorian reader with their own prejudices and make them think the worst of Becky Sharp even when they have no proof of her actions.

Adaptations

Radio

*''Vanity Fair'' (7 January 1940), the CBS Radio series '' Campbell Playhouse'', hosted byOrson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American director, actor, writer, producer, and magician who is remembered for his innovative work in film, radio, and theatre. He is among the greatest and most influential film ...

, broadcast a one-hour adaptation featuring Helen Hayes

Helen Hayes MacArthur (; October 10, 1900 – March 17, 1993) was an American actress. Often referred to as the "First Lady of American Theatre", she was the second person and first woman to win EGOT, the EGOT (an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and ...

and Agnes Moorehead

Agnes Robertson Moorehead (December 6, 1900April 30, 1974) was an American actress. In a career spanning five decades, her credits included work in radio, stage, film, and television.Obituary '' Variety'', May 8, 1974, page 286. Moorehead was th ...

.

*''Vanity Fair'' (6 December 1947), the NBC Radio

The National Broadcasting Company's NBC Radio Network (also known as the NBC Red Network from 1927 to 1942) was an American commercial radio network which was in continuous operation from 1926 through 1999. Along with the NBC Blue Network, it wa ...

series ''Favorite Story

''Favorite Story'' is an American old-time radio dramatic anthology. It was nationally syndicated by the Ziv Company from 1946 to 1949. The program was "advertised as a show that 'stands head and shoulders above the finest programs on the air'" ...

'', hosted by Ronald Colman

Ronald Charles Colman (9 February 1891 – 19 May 1958) was an English-born actor who started his career in theatre and silent film in his native country, then emigrated to the United States where he had a highly successful Cinema of the United ...

, broadcast a half-hour adaptation with Joan Lorring

Joan Lorring (born Madeline Ellis; April 17, 1926 – May 30, 2014) was an American actress and singer known for her work in film and theatre. For her role as Bessy Watty in ''The Corn Is Green'' (1945), Lorring was nominated for the Academy Awa ...

as "Becky Sharp"

*''Vanity Fair'' (2004), BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

broadcast an adaptation of the novel by Stephen Wyatt

Stephen Wyatt, born 4 February 1948 in Beckenham, Kent (now Greater London), is a British writer for theatre, radio and television.

Early life and education

Wyatt was raised in Ealing, West London. He was educated at Latymer Upper School and ...

, starring Emma Fielding

Emma Georgina Annalies Fielding (born 7 October 1970) is an English actress.

Early life and education

The daughter of a British Army officer, Fielding spent some of her childhood in Nigeria, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Northern Ireland and other ...

as Becky, Stephen Fry

Sir Stephen John Fry (born 24 August 1957) is an English actor, broadcaster, comedian, director, narrator and writer. He came to prominence as a member of the comic act Fry and Laurie alongside Hugh Laurie, with the two starring in ''A Bit of ...

as the Narrator, Katy Cavanagh

Kathryn Sarah Collins Jupe (born 12 December 1973), known professionally as Katy Cavanagh, is an English actress. She is known for portraying the role of Julie Carp in the ITV soap opera ''Coronation Street'' (2008–2015, 2025). She also had ...

as Amelia, David Calder, Philip Fox, Jon Glover

Jonathan Philip Glover (born 26 December 1952) is an English actor. He has appeared in various television programmes including '' Play School'', '' Survivors'', the Management consultant in ''The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy'', ''Casualty' ...

, Geoffrey Whitehead

Geoffrey Whitehead (born 1 October 1939) is an English actor. He has appeared in a range of television, film and radio roles.

Early life

Whitehead was born on 1 October 1939 in Grenoside, Sheffield. After his father was killed in the Second Wo ...

as Mr. Osborne, Ian Masters as Mr. Sedley, Alice Hart as Maria Osborne, and Margaret Tyzack

Margaret Maud Tyzack (9 September 193125 June 2011) was an English actress. Her television roles included '' The Forsyte Saga'' (1967) '' I, Claudius'' (1976), and George Lucas's '' Young Indiana Jones'' (1992–1993). She won the 1970 BAFTA TV ...

as Miss Crawley; this was subsequently re-broadcast on BBC Radio 4 Extra

BBC Radio 4 Extra (formerly BBC Radio 7) is a British digital radio station owned and operated by the BBC. It mostly broadcasts archived repeats of comedy, drama and documentary programmes, and is the sister station of Radio 4. It is the pri ...

in 20 fifteen-minute episodes.

*''Vanity Fair'' (2019), BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

broadcast a three-part adaptation of the novel by Jim Poyser with additional material by Al Murray

Alastair James Hay Murray (born 10 May 1968) is an English comedian.

After graduating from the University of Oxford, Murray's comedy career began by working with Harry Hill for BBC Radio 4. He regularly performed at the Edinburgh Festival Frin ...

(Thackeray's actual descendant, who also stars as Thackeray), with Ellie White as Becky Sharp, Helen O'Hara as Amelia Sedley, Blake Ritson

Blake Adam Ritson (born 14 January 1978) is an English actor.

Early life

Ritson was born on 14 January 1978 in London and attended the Dolphin School in Reading, Berkshire until 1993, before going to St Paul's School in West London on an aca ...

as Rawdon Crawley, Rupert Hill

Rupert Sinclair Hill (born 15 June 1978) is an English actor. He is known for his roles in several soap operas.

Career

Hill started with small roles on television. He appeared in an episode of ''EastEnders'' as Robbie's half-brother Kevin Bo ...

as George Osborne and Graeme Hawley

Graeme Hawley (born 25 February 1975) is an English actor. He is best known for his roles as Dave then as DC Martin Crowe in ''Emmerdale'' and John Stape in the British soap ''Coronation Street''.

Career

Hawley graduated from Manchester Metrop ...

as Dobbin.

Silent films

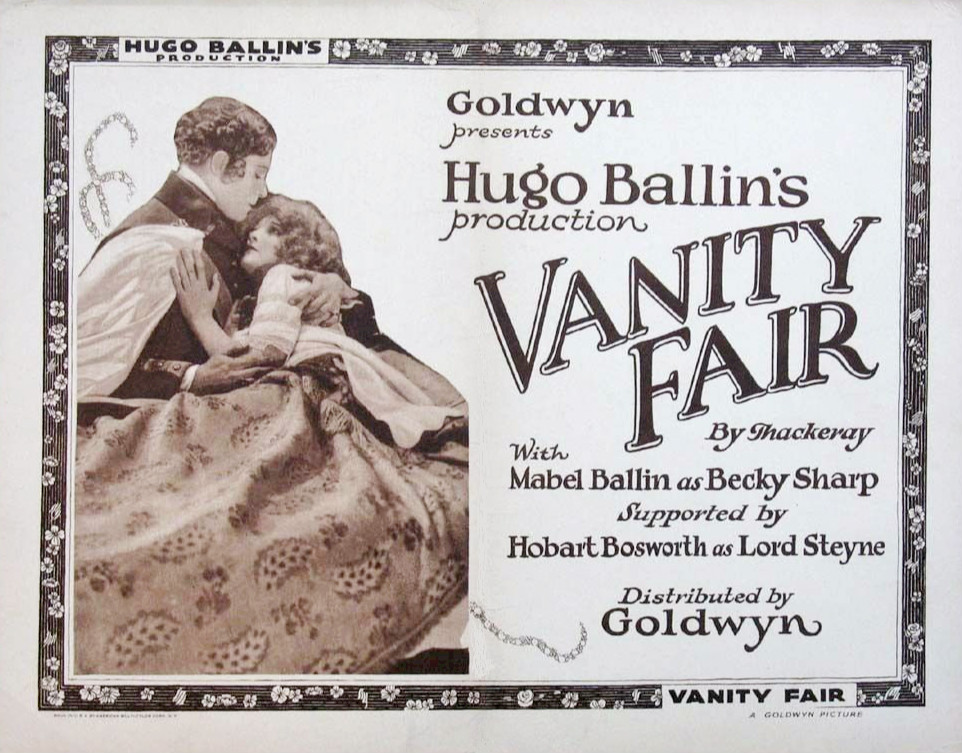

*''Vanity Fair'' (1911), directed by Charles Kent * ''Vanity Fair'' (1915), directed by Charles Brabin *'' Vanity Fair'' (1922), directed by W. Courtney Rowden *'' Vanity Fair'' (1923), directed byHugo Ballin

Hugo Ballin (March 7, 1879 – November 27, 1956) was an American artist, muralist, author, and film director. Ballin was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the National Academy of Design.

Biography

Ballin was born in New ...

Sound films

*'' Vanity Fair'' (1932), directed by Chester M. Franklin and starringMyrna Loy

Myrna Loy (born Myrna Adele Williams; August 2, 1905 – December 14, 1993) was an American film, television and stage actress. As a performer, she was known for her ability to adapt to her screen partner's acting style.

Born in Helena, Monta ...

, updating the story to make Becky Sharp a social-climbing governess

*''Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

'' (1935), starring Miriam Hopkins

Ellen Miriam Hopkins (October 18, 1902 – October 9, 1972) was an American actress known for her versatility. She signed with Paramount Pictures in 1930.

She portrayed a pickpocket in Ernst Lubitsch's romantic comedy '' Trouble in Paradise'', ...

and Frances Dee

Frances Marion Dee (November 26, 1909 – March 6, 2004) was an American actress. Her first film was the musical ''Playboy of Paris'' (1930). She starred in the film ''An American Tragedy (film), An American Tragedy'' (1931). She is also known ...

, the first feature film shot in full-spectrum Technicolor

*'' Vanity Fair'' (2004), directed by Mira Nair

Mira Nair (born 15 October 1957) is an Indian-American filmmaker based in New York City. Her production company is Mirabai Films. Among her films are '' Mississippi Masala'', '' The Namesake'', the Golden Lion–winning '' Monsoon Wedding'', ...

and starring Reese Witherspoon

Laura Jeanne Reese Witherspoon (born March 22, 1976) is an American actress and producer. She is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Reese Witherspoon, various accolades, including an Academy Award, a Primetime Emmy Aw ...

as Becky Sharp and Natasha Little

Natasha Emma Little (born 2 October 1969) is an English actress. She is best known for her roles as Edith Thompson in the film '' Another Life'', Lady Caroline Langbourne in the BBC miniseries '' The Night Manager'', and Christina Moxam in the B ...

, who had played Becky Sharp in the earlier television miniseries of ''Vanity Fair'', as Lady Jane Sheepshanks

Television

*'' Vanity Fair'' (1956-7), aBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

serial adapted by Constance Cox

Constance Cox (25 October 1912 – 8 July 1998) was a British script writer and playwright, born in Sutton, London, Sutton, Surrey.

Life and career

Cox was born Constance Shaw in Sutton, Surrey, in 1912. She married Norman Cox, a fighter pilo ...

starring Joyce Redman

Joyce Olivia Redman (7 December 1915Jonathan Croall, "Redman, Joyce Olivia (1915–2012)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, Jan 201available online Retrieved 1 April 2020. – 9 May 2012) was an Anglo-Irish a ...

*'' Vanity Fair'' (1967), a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

miniseries adapted by Rex Tucker

Rex Tucker (20 February 1913 – 10 August 1996) was a British television director in the 1950s and 1960s.

Early life

He was born in March in the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire. He attended Cheltenham Grammar School and Jesus College, Cambridge ...

starring Susan Hampshire

Susan Hampshire, Lady Kulukundis (born 12 May 1937), is an English actress. She is a three-time Emmy Award winner, winning for the television dramas, '' The Forsyte Saga'' in 1970, '' The First Churchills'' in 1971, and for '' Vanity Fair'' i ...

as Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

, for which she received an Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the year, each with their own set of rules and award categor ...

in 1973. This version was also broadcast in 1972 in the US on PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

television as part of ''Masterpiece Theatre

''Masterpiece'' (formerly known as ''Masterpiece Theatre'') is a drama anthology television series produced by WGBH Boston. It premiered on PBS on January 10, 1971. The series has presented numerous acclaimed British productions. Many of these ...

''.

*''Yarmarka tshcheslaviya'' (1976), a two-episode TV miniseries directed by Igor Ilyinsky

Igor Vladimirovich Ilyinsky (13 January 1987) was a Soviet and Russian stage and film actor, director and comedian. Hero of Socialist Labour (1974) and People's Artist of the USSR (1949).

Early years

Igor Ilyinsky was born on 24 July 1901 in Mo ...

and Mariette Myatt, staged by the Moscow State Academic Maly Theater of the USSR)

*'' Vanity Fair'' (1987), a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

miniseries starring Eve Matheson

Eve Elisabeth Matheson (born 2 March 1960) is an English actress. She is best known for her roles as Zoe Angell in '' May to December'' and Becky Sharp in the BBC adaptation of the novel '' Vanity Fair''.

Matheson left ''May to December'' after ...

as Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

, Rebecca Saire

Rebecca Saire (born 16 April 1963) is a British actress and writer who gained early attention when, at the age of fourteen, she played Juliet for the ''BBC Television Shakespeare'' series.

Stage

* Sybil in ''Private Lives'' ( National Theatr ...

as Amelia Sedley, James Saxon as Jos Sedley and Simon Dormandy

Simon Dormandy is an English theatre director, teacher and actor. As an actor, he worked with Cheek by Jowl and the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), as well as at The Donmar Warehouse, The Old Vic, Chichester Festival Theatre and The Royal Exc ...

as Dobbin.

*'' Vanity Fair'' (1998), a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

miniseries starring Natasha Little

Natasha Emma Little (born 2 October 1969) is an English actress. She is best known for her roles as Edith Thompson in the film '' Another Life'', Lady Caroline Langbourne in the BBC miniseries '' The Night Manager'', and Christina Moxam in the B ...

as Becky Sharp

Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, later describing herself as Rebecca, Lady Crawley, is the main protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1847–48 novel '' Vanity Fair''. She is presented as a cynical social climber who uses her charms to fascinate ...

*'' Vanity Fair'' (2018), a seven-part ITV and Amazon Studios

Amazon MGM Studios is an American film and television production and distribution company owned by Amazon, and headquartered at the Culver Studios complex in Culver City, California. Launched on November 16, 2010, it took its current name on O ...

adaptation, starring Olivia Cooke as Becky Sharp, Tom Bateman as Captain Rawdon Crawley, and Michael Palin

Sir Michael Edward Palin (; born 5 May 1943) is an English actor, comedian, writer, and television presenter. He was a member of the Monty Python comedy group. He received the BAFTA Academy Fellowship Award, BAFTA Fellowship in 2013 and was knig ...

as Thackeray.

Theatre

* ''Becky Sharp'' (1899), play written by Langdon Mitchell * ''Becky Sharp'' (1924) play written by "Olive Conway" * '' Vanity Fair'' (1946), play written byConstance Cox

Constance Cox (25 October 1912 – 8 July 1998) was a British script writer and playwright, born in Sutton, London, Sutton, Surrey.

Life and career

Cox was born Constance Shaw in Sutton, Surrey, in 1912. She married Norman Cox, a fighter pilo ...

* ''Vanity Fair'' (2017), play written by Kate Hamill

Kate Hamill is an American actress and playwright.

Hamill is known for writing and acting in innovative, contemporary adaptations of classic novels for the stage, including Jane Austen’s ''Sense and Sensibility'', '' Emma'', and ''Pride and Pr ...

* ''Vanity'' (2023), musical written and composed by Bernard J. TaylorFiction

* ''Becky'' (2023), novel written by Sarah MayReferences

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* . * . * . * . * . * . * , reprinted 2009 by Routledge. * * . * .External links

* * *The Victorian Web

– Thackeray's Illustrations to Vanity Fair

– Glossary of foreign words and phrases in Vanity Fair {{Authority control 1848 British novels British novels adapted into films Novels set during the Napoleonic Wars Novels by William Makepeace Thackeray Novels first published in serial form Victorian novels Works originally published in Punch (magazine) British satirical novels British novels adapted into television shows Novels about the Battle of Waterloo Novels set in Waterloo, Belgium Cultural depictions of Napoleon Novels set in the 1810s Novels set in the 1820s Novels set in the 1830s Novels set in Brighton Novels set in London British picaresque novels