Alphonse Laveran on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

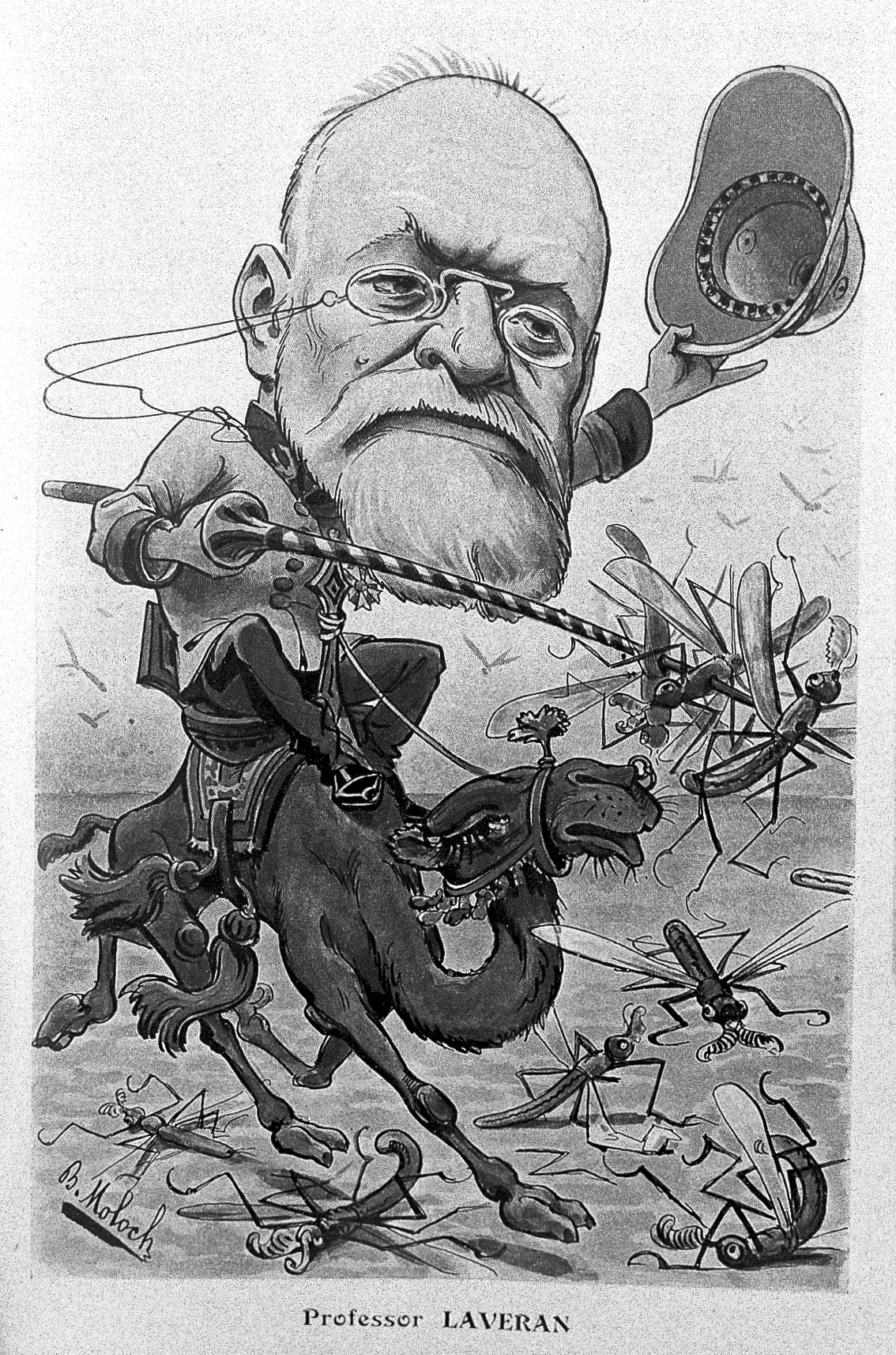

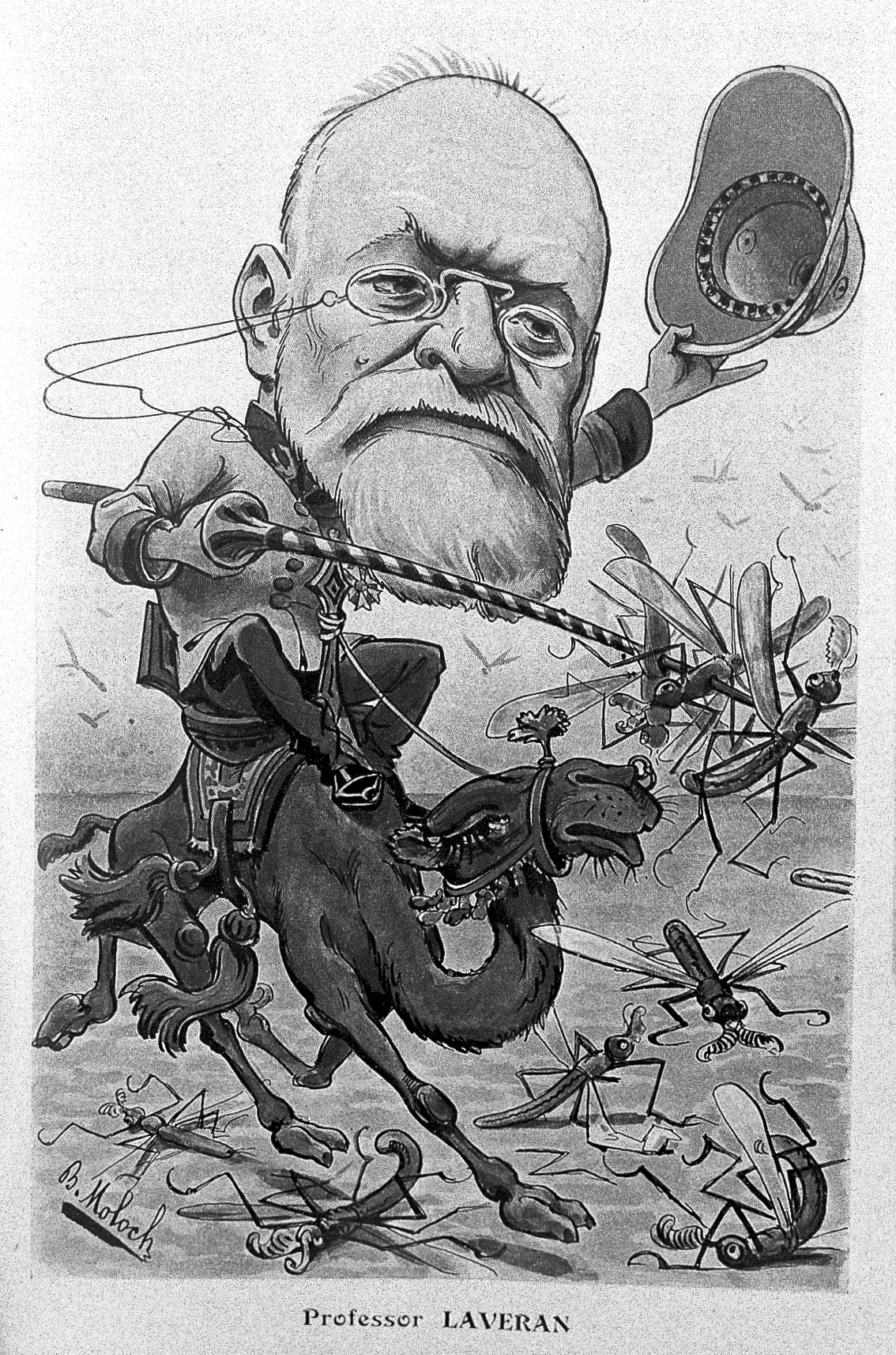

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the

Laveran came across another protozoan disease,

Laveran came across another protozoan disease,

Digital edition

by the

Alphonse Laveran, M. D. 1845–1922

Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopedia of World Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Laveran, Charles Louis Alphonse 1845 births 1922 deaths Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine French atheists French Nobel laureates French tropical physicians Malariologists Members of the French Academy of Sciences Foreign members of the Royal Society Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery University of Strasbourg alumni French parasitologists Pasteur Institute French Army officers French military doctors Recipients of the Cothenius Medal Recipients of the Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The ent ...

protozoans

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

as causative agents of infectious diseases

infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

such as malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and trypanosomiasis

Trypanosomiasis or trypanosomosis is the name of several diseases in vertebrates caused by parasitic protozoan trypanosomes of the genus ''Trypanosoma''. In humans this includes African trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease. A number of other disea ...

. Following his father, Louis Théodore Laveran, he took up military medicine as his profession. He obtained his medical degree from University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

in 1867.

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

in 1870, he joined the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

. At the age of 29 he became Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce. At the end of his tenure in 1878 he worked in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, where he made his major achievements. He discovered that the protozoan parasite ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a Hematophagy, blood-feeding insect host (biology), host which then inj ...

'' was responsible for malaria, and that ''Trypanosoma

''Trypanosoma'' is a genus of kinetoplastids (class Trypanosomatidae), a monophyletic group of unicellular parasitic flagellate protozoa. Trypanosoma is part of the phylum Euglenozoa. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ''trypano-'' (b ...

'' caused trypanosomiasis or African sleeping sickness. In 1894 he returned to France to serve in various military health services. In 1896 he joined Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (, ) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Th ...

as Chief of the Honorary Service, from where he received the Nobel Prize. He donated half of his Nobel prize money to establish the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908, he founded the Société de Pathologie Exotique.

Laveran was elected to French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1893, and was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

in 1912.

Early life and education

Alphonse Laveran was born atBoulevard Saint-Michel

The Boulevard Saint-Michel () is one of the two major streets in the Latin Quarter of Paris, France, the other being the Boulevard Saint-Germain. It is a tree-lined boulevard which runs south from the Pont Saint-Michel on the Seine and Place ...

in Paris, to parents Louis Théodore Laveran and Marie-Louise Anselme Guénard de la Tour Laveran. He was an only son and had an older sister. His family was in a military environment. His father was an army doctor and a professor of military medicine and epidemiology at the medical school, École de Val-de-Grâce in Paris. His mother was the daughter of an army commander.

At a young age, his family moved to Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

in northeast France where his father became professor at the military hospital. At age five, the family moved to Blida

Blida () is a city in Algeria. It is the capital of Blida Province, and it is located about 45 km south-west of Algiers, the national capital. The name ''Blida'', i.e. ''bulaydah'', is a diminutive of the Arabic word ''belda'', city.

Ge ...

in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, North Africa. 1856, he returned to Paris for education, and completed his higher education from Collège Sainte-Barbe

The Collège Sainte-Barbe () is a former college in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France.

The Collège Sainte-Barbe was founded in 1460 on Montagne Sainte-Geneviève ( Latin Quarter, Paris). It was until its closure in June 1999 the "oldest ...

and obtained the bachelor's degree in science ( baccalaureate) from the Lycée Louis-le-Grand

The Lycée Louis-le-Grand (), also referred to simply as Louis-le-Grand or by its acronym LLG, is a public Lycée (French secondary school, also known as sixth form college) located on Rue Saint-Jacques (Paris), rue Saint-Jacques in central Par ...

. Following his father he chose military medicine and entered the public health schools, simultaneously at École Impériale du Service de Santé Militaire (Saint Martin Military Hospital) in Paris and the Faculté de Médecine (Department of Medicine) of the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

in 1863. In 1866, he became a resident medical student in the Strasbourg civil hospitals. In 1867, he submitted a thesis titled ''Recherches expérimentales sur la régénération des nerfs'' (''Research Experiments on the'' ''Regeneration of Nerves'') by which he earned his medical degree from the University of Strasbourg.

Career

Laveran was appointed Aide-major at the Saint Martin Military Hospital soon after his graduation. During theFranco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, he served in the French Army as Medical Assistant-Major. After serving at the battles of Gravelotte

Gravelotte (; ) is a commune in the Moselle department in Grand Est in north-eastern France, 11 km west of Metz. It is part of the functional area (''aire d'attraction'') of Metz. Its population is 827 (2019).

From 1871 until the end of ...

and Saint-Privat, he was posted to Metz, where the French were eventually defeated and the place occupied by Germans. He was briefly taken as prisoner-of-war, but as a physician, he was sent to work at Lille

Lille (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city in the northern part of France, within French Flanders. Positioned along the Deûle river, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Prefectures in F ...

hospital where he remained till the end of the war in 1871.

As a civil war immediately followed (the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

from 18 March to 28 May 1871), he was stationed at the Saint Martin Military Hospital. In 1874, he qualified a competitive examination by which he was appointed to the Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, a position his father had occupied. His tenure ended in 1878 and he was sent to Algeria, where he remained until 1883. Working at military hospitals in Bône (now Annaba

Annaba (), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River and is in the Annaba Province. With a population of about 263,65 ...

) and Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine g ...

, he began to have experience in the study of blood infection as malaria was prevalent. However, he was transferred to Biskra

Biskra () is the capital city of Biskra Province, Algeria. In 2007, its population was recorded as 307,987. Biskra is located in northeastern Algeria, about from Algiers, southwest of Batna, Algeria, Batna and north of Touggourt. It is nickna ...

where there were no malarial cases and he investigated a disease called Biskra button. He returned to Constantine in 1880.

From 1884 to 1889, Laveran was Professor of Military Hygiene at the École de Val-de-Grâce. In 1894 he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the military hospital at Lille and then Director of Health Services of the 11th Army Corps at Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

. By then he was promoted to the rank of Principal Medical Officer of the First Class. In 1896, he entered the Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service to pursue full-time research on tropical diseases.

Achievements

Malaria and discovery of malarial parasite

Laveran had first encounter with malarial parasites while working at Constantine. Malaria was till then considered as a miasmatic disease, a sort of mystical airborne infection. From the blood samples of malarial individuals, Laveran observed pigmented cells (later known ashaemozoin

Haemozoin is a disposal product formed from the digestion of blood by some blood-feeding parasites. These hematophagous organisms such as malaria parasites (''Plasmodium spp.''), ''Rhodnius'' and ''Schistosoma'' digest haemoglobin and release hig ...

which indicate infection of red blood cells with malarial parasite). He knew that German physician Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow ( ; ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder o ...

had described the malarial pigment in 1849. Virchow had seen from a person who died of malaria several pigmented cells in the blood showed for the first time the link between blood infection and malaria. However, he mistakenly identified the pigmented cells as those of endothelial cells

The endothelium (: endothelia) is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the res ...

from the spleen and white blood cells. Malarial infection therefore erroneously known as pigmented white blood cells (melaniferous leucocytes). Laveran was the first to think of such infected blood cells were by parasites, but his interest in the issue was ended by his transfer to non-malarial station.

Soon after he returned to the military hospital

A military hospital is a hospital owned or operated by a military. They are often reserved for the use of military personnel and their dependents, but in some countries are made available to civilians as well. They may or may not be located on a m ...

in Constantine, Algeria, in 1880, Laveran discovered the cause of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

as a protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

n, after observing the parasites in a blood smear

A blood smear, peripheral blood smear or blood film is a thin layer of blood smeared on a glass microscope slide and then stained in such a way as to allow the various blood cells to be examined microscopically. Blood smears are examined in the i ...

taken from a person who had just died of malaria. On 20 October, he first noticed the parasite in various forms and described it with, as later remarked, "accurate" and "excellent freehand drawings." His initial hunch that pigmented cells in malaria were due to parasitic infection became obvious as he observed not only pigmented cells, but also several cells with filaments that were moving about. He continued to investigate other cases of malaria and reported his discoveries on 24 December to the Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris. He described three unique biological characters of malarial parasite: crescent or oval bodies that were transparent and had rounded pigment granules at the centre, spherical bodies that possessed three to four filaments capable of worm-like movements, and smaller spherical bodies that had small granules and lacked filaments. The crescent or oval cells are now known as the gametocytes, filamented bodies as exflagellation (male gamete), and small spherical bodies as trophozoites.

Laveran's report was published in 1881 in the ''Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris'', and in English in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, founded in England in 1823. It is one of the world's highest-impact academic journals and also one of the oldest medical journals still in publication.

The journal publishes ...

.'' He wrote:On the 20th October last, while examining by microscope the blood of a patient suffering from malarial fever I observed in the midst of the red blood corpuscles the presence of elements which appeared to me to be of parasitic origin. Since then I have examined 44 cases, and in 26 have found the same elements. I have searched in vain for these elements in the blood of patients suffering from diseases other than malaria.The same year he published a 104-paged monograph ''Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme: description d’un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre'' (''Parasitic Nature of Malarial Disease: Description of a New Parasite Found in the Blood of Patients with Malarial Fever''). In it, he named the parasite ''Oscillaria malariae'' (which after a long line of research and nomenclature controversies the

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

officially renamed ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans and is the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mos ...

'' in 1954). This was the first time that protozoans were shown to be a cause of disease of any kind. The discovery was therefore a validation of the germ theory of diseases

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

.

However, Laveran's announcement was received with skepticism mainly because by that time leading physicians such as Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli claimed that they had discovered a bacterium (which they called ''Bacillus malariae'') as the pathogen of malaria. Laveran's discovery was widely accepted only after five years when Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) bet ...

confirmed the parasite using better microscope and staining technique.

Laveran was a supporter of the mosquito-malaria theory

Mosquito-malaria theory (or sometimes mosquito theory) was a scientific theory developed in the latter half of the 19th century that solved the question of how malaria was transmitted. The theory proposed that malaria was transmitted by mosquitoe ...

developed by British physician Patrick Manson

Sir Patrick Manson (3 October 1844 – 9 April 1922) was a Scottish physician who made important discoveries in parasitology, and was a founder of the field of tropical medicine.

He graduated from the University of Aberdeen with degrees in Ma ...

in 1894, and experimentally proved by Ronald Ross

Sir Ronald Ross (13 May 1857 – 16 September 1932) was a British medical doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria, becoming the first British Nobel laureate, and the f ...

in 1898. Based on this medical development, he reported malaria condition of Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

in 1901 urging the need for eradication and control of mosquitos. The French Academy of Medicine

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), a ...

established Ligue corse contre le Paludisme (The League of Corsica to Combat Malaria) with Laveran as its honorary president in 1902.

Leishmaniasis

Laveran came across another protozoan disease,

Laveran came across another protozoan disease, cutaneous leishmaniasis

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form of leishmaniasis affecting humans. It is a skin infection caused by a Trypanosomatid, single-celled parasite that is Vector (epidemiology), transmitted by the bite of a Phlebotominae, phlebotomine s ...

, caused by different species of ''Leishmania

''Leishmania'' () is a genus of parasitic protozoans, single-celled eukaryotic organisms of the trypanosomatid group that are responsible for the disease leishmaniasis. The parasites are transmitted by sandflies of the genus '' Phlebotomus'' ...

'', at Biskra, where it was known as clou de Briska (Biskra button) because of the obvious button-like skin sores in infected individuals. Although he failed to make valuable observations, he was the first to identify the causative protozoan of a similar disease, now called visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar (Hindi: kālā āzār, "black sickness") or "black fever", is the most severe form of leishmaniasis and, without proper diagnosis and treatment, is associated with high fatality. Leishmaniasi ...

. In 1903, while at the Pasteur Institute, he received the specimens from a British medical officer Charles Donovan from Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

, India, and with the help of his colleague Félix Mesnil

Félix Étienne Pierre Mesnil ( Omonville-la-Petite, La Manche department, 12 December 1868 – 15 February 1938, Paris) was a French zoologist, biologist, botanist, mycologist and algologist.

He was a student of Alfred Giard at the École Norm ...

, he named it ''Piroplasma donovanii''. However, the scientific name was corrected to ''Leishmania donovani

''Leishmania donovani'' is a species of intracellular parasites belonging to the genus ''Leishmania'', a group of haemoflagellate kinetoplastids that cause the disease leishmaniasis. It is a human blood parasite responsible for visceral leishm ...

'' the same year. In 1904, he and M. Cathoire reported the first case of infantile leishmaniasis from Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

. He published a treatise on leishmaniasis in 1917.

Trypanosomiasis

Laveran later worked on thetrypanosomes

Trypanosomatida is a group of kinetoplastid unicellular organisms distinguished by having only a single flagellum. The name is derived from the Greek language, Greek ''trypano'' (borer) and ''soma'' (body) because of the corkscrew-like motion of ...

and showed once again that the protozoans were responsible for the disease such as sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is caused by the species '' Trypanosoma b ...

and animal trypanosomiasis

Trypanosomiasis or trypanosomosis is the name of several diseases in vertebrates caused by parasitic protozoan trypanosomes of the genus ''Trypanosoma''. In humans this includes African trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease. A number of other disea ...

. He described ''Trypanosoma theileri'' from cattle in 1902; ''Trypanosoma nanum'' in 1905 and ''Trypanosoma Montgomeryi'' in 1909, which were later corrected as ''Trypanosoma congolense

''Trypanosoma congolense'' is a species of trypanosomes and is the major pathogen responsible for the disease nagana in cattle and other animals including sheep, pigs, goats, horses and camels, dogs, as well as laboratory mice. It is the most c ...

'', a parasite of nagana in cattle and horses. With Mesnil, he identified ''Trypanosoma granulosum'' from European eels in 1902; ''Trypanoplasma borelli'' and ''Trypanosoma raiae'' from fish in 1902; ''Trypanosoma danilewskyi'' from fish in 1904; and published a monograph ''Trypanosomes and Trypanosomiases'' (''Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases'') in 1904 by which more than thirty new species were described.

Awards and honours

Laveran was awarded the Bréant Prize (''Prix Bréant'') of the French Academy of Sciences in 1889 and theEdward Jenner Medal

The Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine, formerly known as the Jenner Memorial Medal or the Jenner Medal of the Epidemiological Society of London, is awarded from time to time by the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM), London, at the recom ...

of the Royal Society of Medicine

The Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) is a medical society based at 1 Wimpole Street, London, UK. It is a registered charity, with admission through membership. Its Chief Executive is Michele Acton.

History

The Royal Society of Medicine (R ...

in 1902 for his discovery of the malarial parasite. He received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1907 "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases." He gave half the Prize for foundation of the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. He was honorary fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was establis ...

, Royal Society of Medicine, Pathological Society

The Pathological Society is a professional organization of Great Britain and Ireland whose mission is stated as 'understanding disease'.

Membership and profile

The membership of the society is mainly drawn from the UK and includes an internatio ...

, Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, more commonly known by its acronym RSTMH, was founded in 1907 by Sir James Cantlie and George Carmichael Low. Sir Patrick Manson, the Society's first President (1907–1909), was recognised as ...

, and Royal Society for Public Health

Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) is an independent, multi-disciplinary charity concerned with the improvement of the public's health.

RSPH's Chief Executive is William Roberts, while its current president is Professor Lord Patel of Bradf ...

.

In 1908, he founded the Société de pathologie exotique

Groupe Lactalis S.A. (doing business as Lactalis) is a French multinational dairy products corporation, owned by the Besnier family and based in Laval, Mayenne, France. The company's former name was Besnier S.A.

Lactalis is the largest dairy pr ...

, over which he presided for 12 years. He was elected to membership in the French Academy of Sciences in 1893, and became its President 1920. He was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

in 1912. He was Honorary Director of the Pasteur Institute in 1915 on his 70th birthday. His work was commemorated philatelically on a stamp issued by Algeria in 1954.

Personal life and death

Laveran married Sophie Marie Pidancet in 1885. They had no children. In 1922 he suffered from an unspecified illness for some months and died in Paris. He is interred in theCimetière du Montparnasse

Montparnasse Cemetery () is a cemetery in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris, in the city's 14th arrondissement. The cemetery is roughly 47 acres and is the second largest cemetery in Paris. The cemetery has over 35,000 graves, and approximately 1 ...

in Paris. He was an atheist.

Recognition

Laveran's name features on the Frieze of theLondon School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a member institution of the University of London that specialises in public health and tropical medicine. The institu ...

. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

Works

Laveran was a solitary but dedicated researcher and he wrote more than 600 scientific communications. Some of his major books are: *''Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme, description d'un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre''. Paris 1881 *''Traité des fièvres palustres avec la description des microbes du paludisme''. Paris 1884 *''Traité des maladies et épidémies des armées''. Paris 1875 * ''Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases'' . Masson, Paris 190Digital edition

by the

University and State Library Düsseldorf

The University and State Library Düsseldorf (, abbreviated ULB Düsseldorf) is a central service institution of Heinrich Heine University. Along with Bonn and Münster, it is also one of the three State Libraries of North Rhine-Westphalia.

...

References

Further reading

Alphonse Laveran, M. D. 1845–1922

External links

* including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1907 ''Protozoa as Causes of Diseases''Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopedia of World Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Laveran, Charles Louis Alphonse 1845 births 1922 deaths Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine French atheists French Nobel laureates French tropical physicians Malariologists Members of the French Academy of Sciences Foreign members of the Royal Society Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery University of Strasbourg alumni French parasitologists Pasteur Institute French Army officers French military doctors Recipients of the Cothenius Medal Recipients of the Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine