Almohad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African

The successors of Abd al-Mumin, Abu Yaqub Yusuf (Yusuf I, ruled 1163–1184) and Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur (Yaʻqūb I, ruled 1184–1199), were both able men. Initially their government drove many Jewish and Christian subjects to take refuge in the growing Christian states of Portugal, Castile, and

The successors of Abd al-Mumin, Abu Yaqub Yusuf (Yusuf I, ruled 1163–1184) and Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur (Yaʻqūb I, ruled 1184–1199), were both able men. Initially their government drove many Jewish and Christian subjects to take refuge in the growing Christian states of Portugal, Castile, and

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214), the successor of al-Mansur, after an initially successful advance north, was defeated by an alliance of the three Christian kings of Castile, Aragón and

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214), the successor of al-Mansur, after an initially successful advance north, was defeated by an alliance of the three Christian kings of Castile, Aragón and

The departure of al-Ma'mun in 1228 marked the end of the Almohad era in Spain. Ibn Hud and the other local Andalusian strongmen were unable to stem the rising flood of Christian attacks, launched almost yearly by Sancho II of Portugal,

The departure of al-Ma'mun in 1228 marked the end of the Almohad era in Spain. Ibn Hud and the other local Andalusian strongmen were unable to stem the rising flood of Christian attacks, launched almost yearly by Sancho II of Portugal,

Most historical records indicate that the Almohads were recognized for their use of white banners, which were supposed to evoke their "purity of purpose". This began a long tradition of using white as main dynastic color in what is now Morocco for the later Marinids and Saadian sultanates. Whether these white banners contained any specific motifs or inscriptions is not certain. Historian Ḥasan 'Ali Ḥasan writes:

According to historian Amira Benninson, the caliphs usually left their capital Marrakesh for war in al-Andalus preceded by the white banner of the Almohads, the Quran of 'Uthman and Quran of Ibn Tumart. Egyptian historiographer Al-Qalqashandi (d. 1418) mentioned white flags in two places, the first being when he spoke about the Almohad flag in Tunisia, where he stated that: "It was a white flag called the victorious flag, and it was raised before their sultan when riding for

Most historical records indicate that the Almohads were recognized for their use of white banners, which were supposed to evoke their "purity of purpose". This began a long tradition of using white as main dynastic color in what is now Morocco for the later Marinids and Saadian sultanates. Whether these white banners contained any specific motifs or inscriptions is not certain. Historian Ḥasan 'Ali Ḥasan writes:

According to historian Amira Benninson, the caliphs usually left their capital Marrakesh for war in al-Andalus preceded by the white banner of the Almohads, the Quran of 'Uthman and Quran of Ibn Tumart. Egyptian historiographer Al-Qalqashandi (d. 1418) mentioned white flags in two places, the first being when he spoke about the Almohad flag in Tunisia, where he stated that: "It was a white flag called the victorious flag, and it was raised before their sultan when riding for

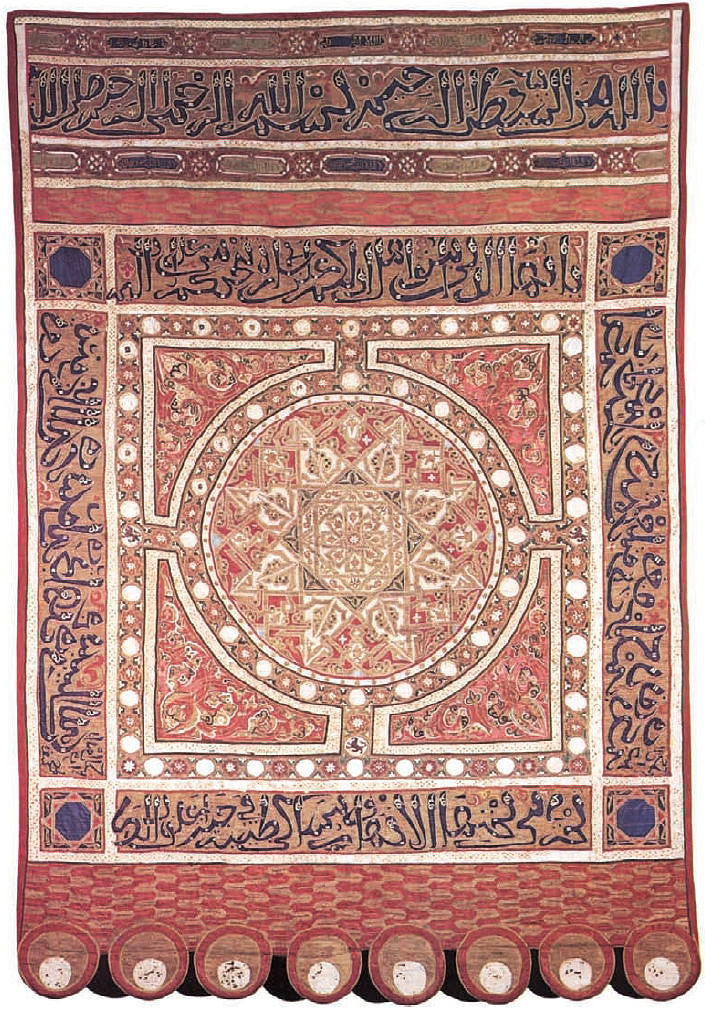

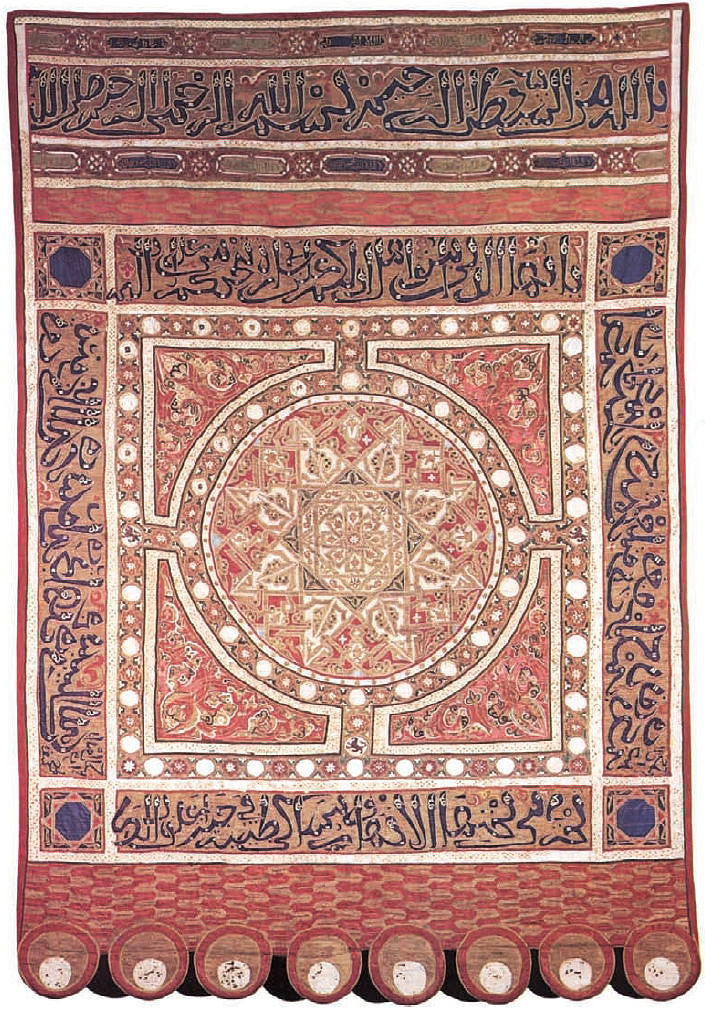

The Almohads initially eschewed the production of luxury textiles and silks, but eventually they too engaged in this production. Almohad textiles, like earlier Almoravid examples, were often decorated with a grid of roundels filled with ornamental designs or Arabic epigraphy. However, textiles produced by Almohad workshops used progressively less figural decoration than previous Almoravid textiles, in favour of interlacing geometric and vegetal motifs.

One of the best-known textiles traditionally attributed to the Almohads is the "Las Navas de Tolosa Banner", so-called because it was once thought to be a spoil won by Alfonso VIII at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. More recent studies have proposed that it was actually a spoil won some years later by Ferdinand III. The banner was then donated to the Monastery of Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas in Burgos, where it remains today. The banner is richly designed and features blue Arabic inscriptions and white decorative patterns on a red background. The central motif features an eight-pointed star framed by a circle inside a larger square, with smaller motifs filling the bands of the frame and the corner spaces. This central design is surrounded on four sides by Arabic inscriptions in Naskhi script featuring Qur'anic verses ( ''Surah'' 61: 10–12), and another horizontal inscription in the banner's upper part which praises God and

The Almohads initially eschewed the production of luxury textiles and silks, but eventually they too engaged in this production. Almohad textiles, like earlier Almoravid examples, were often decorated with a grid of roundels filled with ornamental designs or Arabic epigraphy. However, textiles produced by Almohad workshops used progressively less figural decoration than previous Almoravid textiles, in favour of interlacing geometric and vegetal motifs.

One of the best-known textiles traditionally attributed to the Almohads is the "Las Navas de Tolosa Banner", so-called because it was once thought to be a spoil won by Alfonso VIII at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. More recent studies have proposed that it was actually a spoil won some years later by Ferdinand III. The banner was then donated to the Monastery of Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas in Burgos, where it remains today. The banner is richly designed and features blue Arabic inscriptions and white decorative patterns on a red background. The central motif features an eight-pointed star framed by a circle inside a larger square, with smaller motifs filling the bands of the frame and the corner spaces. This central design is surrounded on four sides by Arabic inscriptions in Naskhi script featuring Qur'anic verses ( ''Surah'' 61: 10–12), and another horizontal inscription in the banner's upper part which praises God and

The French historian Henri Terrasse described al-Qarawiyyin's bronze grand

The French historian Henri Terrasse described al-Qarawiyyin's bronze grand

File:المسجد الأعظم تينمل 7.jpg, Mihrab of the Great Mosque of Tinmal

File:La Giralda, Seville, Spain - Sep 2009.jpg, La Giralda, the former

The Almohads had taken control of the Almoravid Maghribi and Andalusian territories by 1147."Islamic world"

The Almohads had taken control of the Almoravid Maghribi and Andalusian territories by 1147."Islamic world"

''Encyclopædia Britannica Online''. Retrieved September 2, 2007. The Almohads rejected the mainstream Islamic doctrine that established the status of '' dhimmi'', a Non-Muslim resident of a Muslim country who was allowed to practice his religion on condition of submission to Muslim rule and payment of ''

Jewish Trading in Fes On The Eve of the Almohad Conquest

" MEAH, sección Hebreo 56 (2007), 33–51 Then he forced most of the urban ''dhimmi'' population in Morocco, both Jewish and Christian, to convert to Islam. In 1198, the Almohad emir Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur decreed that Jews must wear a dark blue garb, with very large sleeves and a grotesquely oversized hat; his son altered the colour to

pp. 121–122.

/ref> Many Jews fled from territories ruled by the Almohads to Christian lands, and others, like the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands.Frank and Leaman, 2003, pp. 137–138. However, a few Jewish traders still working in North Africa are recorded. Idris al-Ma'mun, a late Almohad pretender (ruled 1229–1232 in parts of Morocco), renounced much Almohad doctrine, including the identification of Ibn Tumart as the Mahdi, and the denial of ''dhimmi'' status. He allowed Jews to practice their religion openly in Marrakesh and even allowed a Christian church there as part of his alliance with Castile. In Iberia, Almohad rule collapsed in the 1200s and was succeeded by several "Taifa" kingdoms, which allowed Jews to practice their religion openly.

Abd al-Mumin life among Masmudas

Encyclopædia Britannica

Al-Andalus: the art of Islamic Spain

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Almohad Caliphate (see index) {{Authority control Caliphates Medieval history of Algeria History of Gibraltar 12th century in Ifriqiya 13th century in Ifriqiya Medieval history of Portugal 11th century in Morocco 12th century in Morocco 13th century in Morocco 12th century in al-Andalus 13th century in al-Andalus Medieval history of Libya States and territories established in 1121 States and territories disestablished in the 1260s 1269 disestablishments Historical transcontinental empires Former countries Former theocracies

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

(Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

) and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

(the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

).

The Almohad movement was founded by Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

among the Berber Masmuda tribes, but the Almohad caliphate and its ruling dynasty, known as the Mu'minid dynasty, were founded after his death by Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

.

* Around 1121, Ibn Tumart was recognized by his followers as the Mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

, and shortly afterwards he established his base at Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. They separate the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range, which stretches around through M ...

. Under Abd al-Mu'min (r. 1130–1163), they succeeded in overthrowing the ruling Almoravid dynasty

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

governing the western Maghreb in 1147, when he conquered Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

and declared himself caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

. They then extended their power over all of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

by 1159. Al-Andalus followed, and all of Muslim Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

was under Almohad rule by 1172.

The turning point of their presence in the Iberian Peninsula came in 1212, when Muhammad al-Nasir (1199–1214) was defeated at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in the Sierra Morena by an alliance of the Christian forces from Castile, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

and Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

. Much of the remaining territories of al-Andalus were lost in the ensuing decades, with the cities of Córdoba and Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

falling to the Christians in 1236 and 1248 respectively.

The Almohads continued to rule in Africa until the piecemeal loss of territory through the revolt of tribes and districts enabled the rise of their most effective enemies, the Marinids in 1215. The last representative of the line, Idris al-Wathiq, was reduced to the possession of Marrakesh, where he was murdered by a slave in 1269; the Marinids seized Marrakesh, ending the Almohad domination of the Western Maghreb.

History

Origins

The Almohad movement originated withIbn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

, a member of the Masmuda, an Amazigh tribal confederation of the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. They separate the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range, which stretches around through M ...

of southern Morocco. At the time, present-day Morocco, Mauritania, western Algeria and parts of Spain and Portugal (al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

) were under the rule of the Almoravids, a Sanhaja Berber dynasty. Early in his life, Ibn Tumart went to Spain to pursue his studies, and thereafter to Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

to deepen them. In Baghdad, Ibn Tumart attached himself to the theological school of al-Ash'ari

Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari (; 874–936 CE) was an Arab Islamic theology, Muslim theologian known for being the eponymous founder of the Ash'ari school of kalam in Sunnism.

Al-Ash'ari was notable for taking an intermediary position between the two ...

, and came under the influence of the teacher al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

. He soon developed his own system, combining the doctrines of various masters. Ibn Tumart's main principle was a strict unitarianism (''tawhid

''Tawhid'' () is the concept of monotheism in Islam, it is the religion's central and single most important concept upon which a Muslim's entire religious adherence rests. It unequivocally holds that God is indivisibly one (''ahad'') and s ...

''), which denied the independent existence of the attributes of God as being incompatible with His unity, and therefore a polytheistic idea. Ibn Tumart represented a revolt against what he perceived as anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It is considered to be an innate tendency of human psychology. Personification is the related attribution of human form and characteristics t ...

in Muslim orthodoxy. His followers would become known as the ''al-Muwaḥḥidūn'' ("Almohads"), meaning those who affirm the unity of God.

After his return to the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

c. 1117, Ibn Tumart spent some time in various Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

n cities, preaching and agitating, heading riotous attacks on wine-shops and on other manifestations of laxity. He laid the blame for the latitude on the ruling dynasty of the Almoravids, whom he accused of obscurantism and impiety. He also opposed their sponsorship of the Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

school of jurisprudence, which drew upon consensus ('' ijma'') and other sources beyond the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

and Sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

in their reasoning, an anathema to the stricter Zahirism favored by Ibn Tumart. His antics and fiery preaching led fed-up authorities to move him along from town to town. After being expelled from Bejaia, Ibn Tumart set up camp in Mellala, in the outskirts of the city, where he received his first disciples – notably, al-Bashir (who would become his chief strategist) and Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

(a Zenata Berber of the Kumiya tribe who would later become his successor).

In 1120, Ibn Tumart and his small band of followers proceeded to Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, stopping first in Fez, where he briefly engaged the Maliki scholars of the city in debate. He even went so far as to assault the sister of the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf, in the streets of Fez, because she was going about unveiled, after the manner of Berber women. After being expelled from Fez, he went to Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, where he successfully tracked down the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf at a local mosque, and challenged the emir, and the leading scholars of the area, to a doctrinal debate. After the debate, the scholars concluded that Ibn Tumart's views were blasphemous and the man dangerous, and urged him to be put to death or imprisoned. But the emir decided merely to expel him from the city.

Ibn Tumart took refuge among his own people, the Hargha, in his home village of Igiliz (exact location uncertain), in the Sous valley. He retreated to a nearby cave, and lived out an ascetic lifestyle, coming out only to preach his program of puritan reform, attracting greater and greater crowds. At length, towards the end of Ramadan

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. It is observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting (''Fasting in Islam, sawm''), communal prayer (salah), reflection, and community. It is also the month in which the Quran is believed ...

in late 1121, after a particularly moving sermon, reviewing his failure to persuade the Almoravids to reform by argument, Ibn Tumart 'revealed' himself as the true Mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

, a divinely guided judge and lawgiver, and was recognized as such by his audience. This was effectively a declaration of war on the Almoravid state.

On the advice of one of his followers, Omar Hintati, a prominent chieftain of the Hintata

The Hintata or Hin Tata were a Berbers, Berber tribal confederation belonging to the tribal group Masmuda of the High Atlas, Morocco. They were historically known for their political power in the region of Marrakesh between the twelfth century an ...

, Ibn Tumart abandoned his cave in 1122 and went up into the High Atlas, to organize the Almohad movement among the highland Masmuda tribes. Besides his own tribe, the Hargha, Ibn Tumart secured the adherence of the Ganfisa, the Gadmiwa, the Hintata, the Haskura, and the Hazraja to the Almohad cause. Sometime around 1124, Ibn Tumart established his base at Tinmel, a highly defensible position in the valley of the Nfis in the High Atlas. Tinmal would serve both as the spiritual center and military headquarters of the Almohad movement. It became their (roughly 'place of retreat'), emulating the story of the '' hijra'' (journey) of Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

's to Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

in the 7th century.

For the first eight years, the Almohad rebellion was limited to a guerilla war along the peaks and ravines of the High Atlas. Their principal damage was in rendering insecure (or altogether impassable) the roads and mountain passes south of Marrakesh – threatening the route to all-important Sijilmassa, the gateway of the trans-Saharan trade. Unable to send enough manpower through the narrow passes to dislodge the Almohad rebels from their easily defended mountain strong points, the Almoravid authorities reconciled themselves to setting up strongholds to confine them there (most famously the fortress of Tasghîmût that protected the approach to Aghmat, which was conquered by the Almohads in 1132), while exploring alternative routes through more easterly passes.

Ibn Tumart organized the Almohads as a commune, with a minutely detailed structure. At the core was the ''Ahl ad-dār'' ("House of the Mahdi"), composed of Ibn Tumart's family. This was supplemented by two councils: an inner Council of Ten

The Council of Ten (; ), or simply the Ten, was from 1310 to 1797 one of the major governing bodies of the Republic of Venice. Elections took place annually and the Council of Ten had the power to impose punishments upon Venetian nobility, patric ...

, the Mahdi's privy council, composed of his earliest and closest companions; and the consultative Council of Fifty, composed of the leading ''sheikh''s of the Masmuda tribes. The early preachers and missionaries (''ṭalaba'' and ''huffāẓ'') also had their representatives. Militarily, there was a strict hierarchy of units. The Hargha tribe coming first (although not strictly ethnic; it included many "honorary" or "adopted" tribesmen from other ethnicities, e.g. Abd al-Mu'min himself). This was followed by the men of Tinmel, then the other Masmuda tribes in order, and rounded off by the black fighters, the ''ʻabīd''. Each unit had a strict internal hierarchy, headed by a ''mohtasib'', and divided into two factions: one for the early adherents, another for the late adherents, each headed by a ''mizwar'' (or ''amzwaru''); then came the ''sakkakin'' (treasurers), effectively the money-minters, tax-collectors, and bursars, then came the regular army (''jund''), then the religious corps – the muezzin

The muezzin (; ), also spelled mu'azzin, is the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer ( ṣalāt) five times a day ( Fajr prayer, Zuhr prayer, Asr prayer, Maghrib prayer and Isha prayer) at a mosque from the minaret. The muezzin ...

s, the ''hafidh'' and the ''hizb'' – followed by the archers, the conscripts, and the slaves. Ibn Tumart's closest companion and chief strategist, al-Bashir, took upon himself the role of " political commissar", enforcing doctrinal discipline among the Masmuda tribesmen, often with a heavy hand.

In early 1130, the Almohads finally descended from the mountains for their first sizeable attack in the lowlands. It was a disaster for their opponents. The Almohads swept aside an Almoravid column that had come out to meet them before Aghmat, and then chased their remnant all the way to Marrakesh. They laid siege to Marrakesh for forty days until, in April (or May) 1130, the Almoravids sallied from the city and crushed the Almohads in the bloody Battle of al-Buhayra (named after a large garden east of the city). The Almohads were thoroughly routed, with huge losses. Half their leadership was killed in action, and the survivors only just managed to scramble back to the mountains.

Caliphate and expansion

Ibn Tumart died shortly after, in August 1130. That the Almohad movement did not immediately collapse after such a devastating defeat and the death of their charismatic Mahdi, is likely due to the skills of his successor,Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

. Ibn Tumart's death was kept a secret for three years, a period which Almohad chroniclers described as a '' ghayba'' or "occultation". This period likely gave Abd al-Mu'min time to secure his position as successor to the political leadership of the movement. Although a Zenata Berber from Tagra (Algeria), and thus an alien among the Masmuda of southern Morocco, Abd al-Mu'min nonetheless saw off his principal rivals and hammered wavering tribes back to the fold. Three years after Ibn Tumart's death he was officially proclaimed "Caliph".

After 1133, Abd al-Mu'min quickly expanded Almohad control across the Maghreb, while the embattled Almoravids retained their capital in Marrakesh. Various other tribes rallied to the Almohads or to the Almoravids as the war between them continued. Initially, Almohad operations were limited to the Atlas mountains. In 1139, they expanded to the Rif mountains in the north. One of their early bases beyond the mountains was Taza

Taza () is a city in northern Morocco occupying the corridor between the Rif mountains and Middle Atlas mountains, about 120 km east of Fez and 150 km south of Al Hoceima. It recorded a population of 148,406 in the 2019 Moroccan ...

, where Abd al-Mu"min founded a citadel (''ribat'') and a Great Mosque circa 1142.

The Almoravid ruler, Ali ibn Yusuf, died in 1143 and was succeeded by his son, Tashfin ibn Ali. The tide turned more definitively in favour of the Almohads from 1144 onwards, when the Zenata tribes in what is now western Algeria joined the Almohad camp, along with some of the previously Almoravid-aligned leaders of the Masufa tribe. This allowed them to defeat Tashfin decisively and capture Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran and is the capital of Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the port of Rachgoun. It had a population of ...

in 1144. Tashfin fled to Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

, which the Almohads then attacked and captured, and he died in March 1145 while trying to escape. The Almohads pursued the defeated Almoravid army west to Fez, which they captured in 1146 after a nine-month siege. They finally captured Marrakesh in 1147, after an eleven-month siege. The last Almoravid ruler, Ishaq ibn Ali, was killed.

In 1151, Abd al-Mu'min launched an expedition to the east. This may have been encouraged by the Norman conquests along the coast of Ifriqiya, as fighting the Christian invaders here gave him a pretext for conquering the rest of the region. In August 1152, he captured Béjaïa

Béjaïa ( ; , , ), formerly known as Bougie and Bugia, is a Mediterranean seaport, port city and communes of Algeria, commune on the Gulf of Béjaïa in Algeria; it is the capital of Béjaïa Province.

Geography

Location

Béjaïa owes its ...

, the capital of the Hammadids. The last Hammadid ruler, Yahya ibn Abd al-Aziz, fled by sea. The Arab tribes of the region, the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym

The Banu Sulaym () is an Arab tribe that dominated part of the Hejaz in the pre-Islamic era. They maintained close ties with the Quraysh of Mecca and the inhabitants of Medina, and fought in a number of battles against the Islamic prophet Muha ...

, reacted to the Almohad advance by gathering an army against them. The Almohads routed them in the Battle of Sétif in April 1153. Abd al-Mu'min nonetheless saw value in their military abilities. He persuaded them by various means – including taking some families as hostages to Marrakesh and more generous actions like offering them material and land incentives – to move to present-day Morocco and join the Almohad armies. These moves also had the corollary effect of advancing the Arabisation of future Morocco.

Abd al-Mu'min spent the mid-1150s organizing the Almohad state and arranging for power to be passed on through his family line. In 1154, he declared his son Muhammad as his heir. In order to neutralise the power of the Masmuda, he relied on his tribe of origin, the Kumiyas (from the central Maghreb), whom he integrated into the Almohad power structure and from whom he recruited some 40,000 into the army. They would later form the bodyguard of the caliph and his successors. In addition, Abd al-Mu'min relied on Arabs, the great Hilalian families that he had deported to Morocco, to further weaken the influence of the Masmuda sheikhs.

With his son appointed as his successor, Abd al-Mu'min placed his other children as governors of the provinces of the caliphate. His sons and descendants became known as the ''sayyid''s ("nobles"). To appease the traditional Masmuda elites, he appointed some of them, along with theirs sons and descendants, to act as important advisers, deputies, and commanders under the ''sayyid''s. They became known as the or "Sons of the Almohads". Abd al-Mu'min also altered the Almohad structure set up by Ibn Tumart by making the ''huffaz'' or reciters of the Quran into a training school of the Almohad elite. They were no longer described as "memorisers" but as "guardians" who learned riding, swimming, archery, and received a general education of high standards.

Abd al-Mu'min thus transformed the Almohads from an aristocratic Masmuda movement to a dynastic Mu'minid state. While most of the Almohad elites accepted this new concentration of power, it nonetheless triggered an uprising by two of Ibn Tumart's half-brothers, 'Abd al-'Aziz and 'Isa. Shortly after Abd al-Mu'min announced his heir, towards 1154–1155, they rebelled in Fez and then marched on Marrakesh, whose governor they killed. Abd al-Mu'min, who had been in Salé, returned to the city, defeated the rebels, and had everyone involved executed.

In March 1159, Abd al-Mu'min led a new campaign to the east. He conquered Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

by force when the local Banu Khurasan leaders refused to surrender. Mahdia

Mahdia ( ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 76,513 inhabitants, south of Monastir, Tunisia, Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

was besieged soon after and surrendered in January 1160. The Normans there negotiated their withdrawal and were allowed to leave for Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. Tripoli, which had rebelled against the Normans two years earlier, recognized Almohad authority right after.

In the 1170s and 1180s, Almohad power in the eastern Maghreb was challenged by the Banu Ghaniya and by Qaraqush, an Ayyubid commander. Yaqub al-Mansur eventually defeated both factions and reconquered Ifriqiya in 1187–1188. In 1189–1190, the Ayyubid sultan Salah ad-Din (Saladin) requested the assistance of an Almohad navy for his fight against the crusaders, which al-Mansur declined.

Expansion into al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

followed the fate of North Africa. Between 1146 and 1173, the Almohads gradually wrested control from the Almoravids over the Muslim principalities in Iberia. The Almohads transferred the capital of Muslim Iberia from Córdoba to Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

. They founded a great mosque there; its tower, the Giralda, was erected in 1184. The Almohads also built a palace there called Al-Muwarak on the site of the modern-day Alcázar of Seville.

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

. Ultimately they became less fanatical than the Almoravids, and Ya'qub al-Mansur was a highly accomplished man who wrote a good Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

style and protected the philosopher Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

. In 1190–1191, he campaigned in southern Portugal and won back territory lost in 1189. His title of "''al-Manṣūr''" ("the Victorious") was earned by his victory over Alfonso VIII of Castile

Alfonso VIII (11 November 11555 October 1214), called the Noble (El Noble) or the one of Las Navas (el de las Navas), was King of Castile from 1158 to his death and King of Toledo. After having suffered a great defeat with his own army at Alarc ...

in the Battle of Alarcos (1195).

From the time of Yusuf II, however, the Almohads governed their co-religionists in Iberia and central North Africa through lieutenants, their dominions outside Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

being treated as provinces. When Almohad emirs crossed the Straits it was to lead a jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

against the Christians and then return to Morocco.

Holding years

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214), the successor of al-Mansur, after an initially successful advance north, was defeated by an alliance of the three Christian kings of Castile, Aragón and

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214), the successor of al-Mansur, after an initially successful advance north, was defeated by an alliance of the three Christian kings of Castile, Aragón and Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in the Sierra Morena. The battle broke the Almohad advance, but the Christian powers remained too disorganized to profit from it immediately.

Before his death in 1213, al-Nasir appointed his young ten-year-old son as the next caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

Yusuf II "al-Mustansir". The Almohads passed through a period of effective regency for the young caliph, with power exercised by an oligarchy of elder family members, palace bureaucrats and leading nobles. The Almohad ministers were careful to negotiate a series of truces with the Christian kingdoms, which remained more-or-less in place for next fifteen years (the loss of Alcácer do Sal to the Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal was a Portuguese monarchy, monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also known as the Kingdom of Portugal a ...

in 1217 was an exception).

In early 1224, the youthful caliph died in an accident, without any heirs. The palace bureaucrats in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, led by the '' wazir'' Uthman ibn Jam'i, quickly engineered the election of his elderly grand-uncle, Abd al-Wahid I 'al-Makhlu', as the new Almohad caliph. But the rapid appointment upset other branches of the family, notably the brothers of the late al-Nasir, who governed in al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. The challenge was immediately raised by one of them, then governor in Murcia, who declared himself Caliph Abdallah al-Adil. With the help of his brothers, he quickly seized control of al-Andalus. His chief advisor, the shadowy Abu Zayd ibn Yujjan, tapped into his contacts in Marrakesh, and secured the deposition and assassination of Abd al-Wahid I, and the expulsion of the al-Jami'i clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

.

This coup has been characterized as the pebble that finally broke al-Andalus. It was the first internal coup among the Almohads. The Almohad clan, despite occasional disagreements, had always remained tightly knit and loyally behind dynastic precedence. Caliph al-Adil's murderous breach of dynastic and constitutional propriety marred his acceptability to other Almohad ''sheikh

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning "elder (administrative title), elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim ulama, scholar. Though this title generally refers to me ...

s''. One of the recusants was his cousin, Abd Allah al-Bayyasi ("the Baezan"), the Almohad governor of Jaén, who took a handful of followers and decamped for the hills around Baeza. He set up a rebel camp and forged an alliance with the hitherto quiet Ferdinand III of Castile. Sensing his greater priority was Marrakesh, where recusant Almohad ''sheikh''s had rallied behind Yahya, another son of al-Nasir, al-Adil paid little attention to them.

Decline in al-Andalus

In 1225, Abd Allah al-Bayyasi's band of rebels, accompanied by a large Castilian army, descended from the hills, besieging cities such as Jaén and Andújar. Theyraid

RAID (; redundant array of inexpensive disks or redundant array of independent disks) is a data storage virtualization technology that combines multiple physical Computer data storage, data storage components into one or more logical units for th ...

ed throughout the regions of Jaén, Cordova and Vega de Granada and, before the end of the year, al-Bayyasi had established himself in the city of Cordova. Sensing a power vacuum, both Alfonso IX of León

Alfonso IX (15 August 117123 or 24 September 1230) was King of León from the death of his father Ferdinand II in 1188 until his own death.

He took steps towards modernizing and democratizing his dominion and founded the University of Salaman ...

and Sancho II of Portugal opportunistically ordered raids into Andalusian territory that same year. With Almohad arms, men and cash dispatched to Morocco to help Caliph al-Adil impose himself in Marrakesh, there was little means to stop the sudden onslaught. In late 1225, with surprising ease, the Portuguese raiders reached the environs of Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

. Knowing they were outnumbered, the Almohad governors of the city refused to confront the Portuguese raiders, prompting the disgusted population of Seville to take matters into their own hands, raise a militia, and go out in the field by themselves. The result was a veritable massacre – the Portuguese men-at-arms easily mowed down the throng of poorly armed townsfolk. Thousands, perhaps as much as 20,000, were said to have been slain before the walls of Seville. A similar disaster befell a similar popular levy by Murcians at Aspe that same year. But Christian raiders had been stopped at Cáceres and Requena. Trust in the Almohad leadership was severely shaken by these events – the disasters were promptly blamed on the distractions of Caliph al-Adil and the incompetence and cowardice of his lieutenants, the successes credited to non-Almohad local leaders who rallied defenses.

But al-Adil's fortunes were briefly buoyed. In payment for Castilian assistance, al-Bayyasi had given Ferdinand III three strategic frontier fortresses: Baños de la Encina, Salvatierra (the old Order of Calatrava

The Order of Calatrava (, ) was one of the Spanish military orders, four Spanish military orders and the first Military order (society), military order founded in Kingdom of Castile, Castile, but the second to receive papal approval. The papal bu ...

fortress near Ciudad Real

Ciudad Real (, ) is a municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile–La Mancha, capital of the province of Ciudad Real. It is the 5th most populated municipality in the region.

It was founded as Villa Real in 1255 as a ro ...

) and Capilla. But Capilla refused to surrender, forcing the Castilians to lay a long and difficult siege. The brave defiance of little Capilla, and the spectacle of al-Bayyasi's shipping provisions to the Castilian besiegers, shocked Andalusians and shifted sentiment back towards the Almohad caliph. A popular uprising broke out in Cordova – al-Bayyasi was killed and his head dispatched as a trophy to Marrakesh. But Caliph al-Adil did not rejoice in this victory for long – he was assassinated in Marrakesh in October 1227, by the partisans of Yahya, who was promptly acclaimed as the new Almohad caliph Yahya "al-Mu'tasim".

The Andalusian branch of the Almohads refused to accept this turn of events. Al-Adil's brother, then in Seville, proclaimed himself the new Almohad caliph Abd al-Ala Idris I 'al-Ma'mun'. He promptly purchased a truce from Ferdinand III in return for 300,000 '' maravedis'', allowing him to organize and dispatch the greater part of the Almohad army in Spain across the straits in 1228 to confront Yahya.

That same year, Portuguese and Leonese renewed their raids deep into Muslim territory, basically unchecked. Feeling the Almohads had failed to protect them, popular uprisings took place throughout al-Andalus. City after city deposed their hapless Almohad governors and installed local strongmen in their place. A Murcian strongman, Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Hud al-Judhami, who claimed descendance from the Banu Hud dynasty that had once ruled the old taifa of Saragossa, emerged as the central figure of these rebellions, systematically dislodging Almohad garrisons through central Spain. In October 1228, with Spain practically all lost, al-Ma'mun abandoned Seville, taking what little remained of the Almohad army with him to Morocco. Ibn Hud immediately dispatched emissaries to distant Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

to offer recognition to the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, albeit taking up for himself a quasi-caliphal title, 'al-Mutawwakil'.

The departure of al-Ma'mun in 1228 marked the end of the Almohad era in Spain. Ibn Hud and the other local Andalusian strongmen were unable to stem the rising flood of Christian attacks, launched almost yearly by Sancho II of Portugal,

The departure of al-Ma'mun in 1228 marked the end of the Almohad era in Spain. Ibn Hud and the other local Andalusian strongmen were unable to stem the rising flood of Christian attacks, launched almost yearly by Sancho II of Portugal, Alfonso IX of León

Alfonso IX (15 August 117123 or 24 September 1230) was King of León from the death of his father Ferdinand II in 1188 until his own death.

He took steps towards modernizing and democratizing his dominion and founded the University of Salaman ...

, Ferdinand III of Castile and James I of Aragon. The next twenty years saw a massive advance in the Christian reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

– the old great Andalusian citadel

A citadel is the most fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of ''city'', meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

...

s fell in a grand sweep: Mérida and Badajoz

Badajoz is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portugal, Portuguese Portugal–Spain border, border, on the left bank of the river ...

in 1230 (to Leon), Mallorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest of the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, seventh largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

The capital of the island, Palma, Majorca, Palma, i ...

in 1230 (to Aragon), Beja in 1234 (to Portugal), Córdoba in 1236 (to Castile), Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

in 1238 (to Aragon), Niebla- Huelva in 1238 (to Leon), Silves in 1242 (to Portugal), Murcia in 1243 (to Castile), Jaén in 1246 (to Castile), Alicante

Alicante (, , ; ; ; officially: ''/'' ) is a city and municipalities of Spain, municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean port. The population ...

in 1248 (to Castile), culminating in the fall of the greatest of Andalusian cities, the ex-Almohad capital of Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, into Christian hands in 1248. Ferdinand III of Castile entered Seville as a conqueror on December 22, 1248.

The Andalusians were helpless before this onslaught. Ibn Hud had attempted to check the Leonese advance early on, but most of his Andalusian army was destroyed at the battle of Alange in 1230. Ibn Hud scrambled to move remaining arms and men to save threatened or besieged Andalusian citadels, but with so many attacks at once, it was a hopeless endeavor. After Ibn Hud's death in 1238, some of the Andalusian cities, in a last-ditch effort to save themselves, offered themselves once again to the Almohads, but to no avail. The Almohads would not return.

With the departure of the Almohads, the Nasrid dynasty ("''Banū Naṣr''", ) rose to power in Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

. After the great Christian advance of 1228–1248, the Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada, also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, was an Emirate, Islamic polity in the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Late Middle Ages, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty. It was the last independent Muslim state in Western ...

was practically all that remained of old al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. Some of the captured citadels (e.g. Murcia, Jaen, Niebla) were reorganized as tributary vassals for a few more years, but most were annexed by the 1260s. Granada alone would remain independent for an additional 250 years, flourishing as the new center of al-Andalus.

Collapse in the Maghreb

In their African holdings, the Almohads encouraged the establishment of Christians even in Fez, and after the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa they occasionally entered into alliances with the kings of Castile. The history of their decline differs from that of the Almoravids, whom they had displaced. They were not assailed by a great religious movement, but lost territories, piecemeal, by the revolt of tribes and districts. Their most effective enemies were the Banu Marin ( Marinids) who founded the next dynasty. The last representative of the line, Idris al-Wathiq, was reduced to the possession ofMarrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, where he was murdered by a slave in 1269.

Government

TheCouncil of Ten

The Council of Ten (; ), or simply the Ten, was from 1310 to 1797 one of the major governing bodies of the Republic of Venice. Elections took place annually and the Council of Ten had the power to impose punishments upon Venetian nobility, patric ...

was a group of Ibn Tumart's earliest and closest disciples, at the top of the hierarchy of the Almohad movement.

Culture

Language

The use ofBerber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

was important in Almohad doctrine. Under the Almohads, the ''khuṭba'' (sermon) at Friday prayer was made to be delivered in Arabic and Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

, with the latter referred to as '' al-lisān al-gharbī'' () by the Andalusi historian . For example, the '' khaṭīb'', or sermon-giver, of al-Qarawiyyīn Mosque in Fes, Mahdī b. 'Īsā, was replaced under the Almohads by Abū l-Ḥasan b. 'Aṭiyya khaṭīb because he was fluent in Berber.

As the Almohads rejected the status of ''Dhimma'', the Almohad conquest of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

caused the emigration of Andalusi Christians from southern Iberia to the Christian north, which had an impact on the use of Romance within Almohad territory. After the Almohad period, Muslim territories in Iberia were reduced to the Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada, also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, was an Emirate, Islamic polity in the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Late Middle Ages, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty. It was the last independent Muslim state in Western ...

, in which the percentage of the population that had converted to Islam reached 90% and Arabic-Romance bilingualism seems to have disappeared. ''Cited in''

The French Orientalist Georges-Séraphin Colin—based on a collection of Almohad-era texts heavily influenced by vernacular speech, edited by Évariste Lévi-Provençal—identifies various points of contact and divergence between Andalusi Arabic and Maghrebi Arabic

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, Hassaniya and Saharan Arabic di ...

in the Almohad period.

Literature

The Almohads worked to suppress the influence of the Maliki school of fiqh, even publicly burning copies of ''Muwatta Imam Malik

''Al-Muwaṭṭaʾ'' (, 'the approved') or ''Muwatta Imam Malik'' () of Malik ibn Anas, Imam Malik (711–795) written in the 8th-century, is one of the earliest collections of hadith texts comprising the subjects of Sharia, Islamic law, compile ...

'' and Maliki commentaries. They sought to disseminate ibn Tumart's beliefs; he was the author of the '' Aʿazzu Mā Yuṭlab'', the ''Counterpart of the Muwatta'' (), and the ''Compendium of Sahih Muslim'' ().

Literary production continued despite the Almohad reforms's devastating effect on cultural life in their domain. Almohad universities continued the knowledge of preceding Andalusi scholars as well as ancient Greek and Roman writers; contemporary literary figures included Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

, Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya, ibn Tufayl, ibn Zuhr

Abū Marwān ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr (), traditionally known by his Latinized name Avenzoar (; 1094–1162), was an Arab physician, surgeon, and poet. He was born at Seville in medieval Andalusia (present-day Spain), was a contemporary of A ...

, ibn al-Abbar, ibn Amira and many more poets, philosophers, and scholars. The abolishment of the dhimmi status of religious minorities further stifled the once flourishing Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain; Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

went east and many Jews moved to Castillian-controlled Toledo.

According to the research of Muhammad al-Manuni, there were 400 paper mills in Fes under the reign of Sultan Yaqub al-Mansur in the 12th century.

Theology and philosophy

The Almohad ideology preached by Ibn Tumart is described by Amira Bennison as a "sophisticated hybrid form of Islam that wove together strands fromHadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

science, Zahiri and Shafi'i

The Shafi'i school or Shafi'i Madhhab () or Shafi'i is one of the four major schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It was founded by the Muslim scholar, jurist, and traditionis ...

''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

'', Ghazalian social actions ('' hisba''), and spiritual engagement with Shi'i notions of the Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

and ''mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

''". This contrasted with the highly orthodox or traditionalist Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

school ('' maddhab'') of Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam is the largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any Succession to Muhammad, successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr ...

which predominated in the region up to that point. Central to his philosophy, Ibn Tumart preached a fundamentalist or radical version of ''tawhid

''Tawhid'' () is the concept of monotheism in Islam, it is the religion's central and single most important concept upon which a Muslim's entire religious adherence rests. It unequivocally holds that God is indivisibly one (''ahad'') and s ...

'' – referring to a strict monotheism or to the "oneness of God". This notion gave the movement its name: ''al''-''Muwaḥḥidūn'' (), meaning roughly "those who advocate ''tawhid''", which was adapted to "Almohads" in European writings. Ibn Tumart saw his movement as a revolutionary reform movement much as early Islam saw itself relative to the Christianity and Judaism which preceded it, with himself as its ''mahdi'' and leader.

In terms of Muslim jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

, the state gave recognition to the Zahiri () school of thought, though Shafi'ites were also given a measure of authority at times. While not all Almohad leaders were Zahirites, quite a few of them were not only adherents of the legal school but also well-versed in its tenets. Additionally, all Almohad leaders – both the religiously learned and the laymen – were hostile toward the Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

te school favored by the Almoravids. During the reign of Abu Yaqub, chief judge Ibn Maḍāʾ oversaw the banning of all religious books written by non-Zahirites; when Abu Yaqub's son Abu Yusuf took the throne, he ordered Ibn Maḍāʾ to undertake the actual burning of such books.

In terms of Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding creed. The main schools of Islamic theology include the extant Mu'tazili, Ash'ari, Maturidi, and Athari schools; the extinct ones ...

, the Almohads were Ash'arites, their Zahirite-Ash'arism giving rise to a complicated blend of literalist jurisprudence and esoteric dogmatics. Some authors occasionally describe Almohads as heavily influenced by Mu'tazilism. Scholar Madeline Fletcher argues that while one of Ibn Tumart's original teachings, the ''murshida''s (a collection of sayings memorized by his followers), holds positions on the attributes of God which might be construed as moderately Mu'tazilite (and which were criticized as such by Ibn Taimiyya), identifying him with Mu'tazilites would be an exaggeration. She points out that another of his main texts, the ''logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

al reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

ing as a method of validating the more central Almohad concept of ''tawhid''. This effectively provided a religious justification for philosophy and for a rationalist intellectualism in Almohad religious thought. Al-Mansur's father, Abu Ya'qub Yusuf, had also shown some favour towards philosophy and kept the philosopher Ibn Tufayl as his confidant. Ibn Tufayl in turn introduced Ibn Rush (Averroes) to the Almohad court, to whom Al-Mansur gave patronage and protection. Although Ibn Rushd (who was also an Islamic judge) saw rationalism and philosophy as complementary to religion and revelation, his views failed to convince the traditional Maliki ''ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

'', with whom the Almohads were already at odds. After the decline of Almohadism, Maliki Sunnism ultimately became the dominant official religious doctrine of the region. By contrast, the teachings of Ibn Rushd and other philosophers like him were far more influential for Jewish philosophers – including Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, his contemporary – and Christian Latin scholars – like Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

– who later promoted his commentaries on Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

.

Emblem

Most historical records indicate that the Almohads were recognized for their use of white banners, which were supposed to evoke their "purity of purpose". This began a long tradition of using white as main dynastic color in what is now Morocco for the later Marinids and Saadian sultanates. Whether these white banners contained any specific motifs or inscriptions is not certain. Historian Ḥasan 'Ali Ḥasan writes:

According to historian Amira Benninson, the caliphs usually left their capital Marrakesh for war in al-Andalus preceded by the white banner of the Almohads, the Quran of 'Uthman and Quran of Ibn Tumart. Egyptian historiographer Al-Qalqashandi (d. 1418) mentioned white flags in two places, the first being when he spoke about the Almohad flag in Tunisia, where he stated that: "It was a white flag called the victorious flag, and it was raised before their sultan when riding for

Most historical records indicate that the Almohads were recognized for their use of white banners, which were supposed to evoke their "purity of purpose". This began a long tradition of using white as main dynastic color in what is now Morocco for the later Marinids and Saadian sultanates. Whether these white banners contained any specific motifs or inscriptions is not certain. Historian Ḥasan 'Ali Ḥasan writes:

According to historian Amira Benninson, the caliphs usually left their capital Marrakesh for war in al-Andalus preceded by the white banner of the Almohads, the Quran of 'Uthman and Quran of Ibn Tumart. Egyptian historiographer Al-Qalqashandi (d. 1418) mentioned white flags in two places, the first being when he spoke about the Almohad flag in Tunisia, where he stated that: "It was a white flag called the victorious flag, and it was raised before their sultan when riding for Eid prayers

Eid prayers, also referred to as Salat al-Eid (), are holy holiday prayers in the Islamic tradition. The literal translation of the word "Eid" in Arabic is "festival" or "feast" and is a time when Muslims congregate with family and the larger ...

or for the movement of the makhzen slaves (which were the ordinary people of the country and the people of the markets)". By the end of the Almohad reign, dissident movements would adopt black in recognition of the Abbasid caliphate and in rejection of the Almohad authority.

The '' Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms'', written by a Franciscan friar in the 14th century (well after the end of the Almohad period), describes the flag of Marrakesh as being red with a black-and-white checkerboard motif at its center. Some authors have assumed this flag to be the former flag of the Almohads.

In modern times, Islamic al-Andalus in Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

n collective memory allowed more awareness of the colors of the Andalusian flag, chosen in 1918 by Blas Infante, a founding figure of Andalusia. Infante has explained the design of its flag by indicating that green was the color of the Umayyads and white that of the Almohads, the caliphates which represented periods of "greatness and power" in this region.

Art

Calligraphy and manuscripts

The Almohad dynasty embraced a style of cursiveMaghrebi script

Maghrebi script or Maghribi script or Maghrebi Arabic script () refers to a loosely related family of Arabic scripts that developed in the Maghreb (North Africa), al-Andalus (Iberian Peninsula, Iberia), and Sudan (region), ''Bilad as-Sudan'' (th ...

known today as "Maghrebi thuluth" as an official style used in manuscripts, coinage, documents, and architecture. However, the more angular Kufic script was still used, albeit in a reworked form in Qur'an epigraphy, and was seen detailed in silver in some colophons.Bongianino, Umberto (18 May 2021). ''Untold Stories of Maghrebi Qur'ans (12th-14th centuries)'' (Lecture). The Maghrebi thuluth script, frequently written in gold, was used to give emphasis when standard writing, written in rounded Maghrebi mabsūt script, was considered insufficient. Maghrebi mabsūt of the al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

region during the 12th to 14th centuries was characterized by elongated lines, stretched out curves, and the use of multiple colors for vocalizations, as derived from the people of Medina.

Scribes and calligraphers of the Almohad period also started to illuminate words and phrases in manuscripts for emphasis, using gold leaf and lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color. Originating from the Persian word for the gem, ''lāžward'', lapis lazuli is ...

.Barrucand, Marianne (1995). ''Remarques sur le decor des manuscrit religeux hispano-maghrebin du moyen-age''. Paris: Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. p. 240-243. . While much of the script was written in black or brown ink, the use of polychromy for diacritical text and vocalizations also marked a departure from previous caliphates' calligraphic styles. Blue dots were used to indicate elif, orange dots denoted hamza

The hamza ( ') () is an Arabic script character that, in the Arabic alphabet, denotes a glottal stop and, in non-Arabic languages, indicates a diphthong, vowel, or other features, depending on the language. Derived from the letter '' ʿayn'' ( ...

, and yellow semicircles to marked shaddah. Separate sets of verses were denoted by various medallions, with distinctive designs for each set. For example, sets of five verses were ended with bud-like medallions while sets of ten were marked by circular medallions, all of which were typically painted in gold. Manuscripts attributed to this caliphate were characterized by interlacing geometric or recti-curvilinear illuminations, and abstract vegetal artwork and large medallions were often present in the margins and as thumbnails. Composite floral finial

A finial () or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the Apex (geometry), apex of a dome, spire, tower, roo ...

s were also frequently used in decorating the margins and corners of the page. Color schemes focused on primarily using gold, white, and blue, with accentuating elements in red or pink.

During the Almohad dynasty, the act of bookbinding itself took on great importance, with a notable instance of the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

bringing in artisans for a celebration of the binding of a Qur'an imported from Cordoba. Books were most frequently bound in goatskin leather and decorated with polygonal interlacing, goffering, and stamping. The primary materials used for the pages were goat or sheep vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. It is often distinguished from parchment, either by being made from calfskin (rather than the skin of other animals), or simply by being of a higher quality. Vellu ...

. However, the Almohad dynasty also saw industrial advancements in the spread of paper mills in Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

and Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, leading to the introduction of paper for Qur'an manuscripts, illuminated doctrine books, and official documents.Barrucand, Marianne (2005). ''Les Enluminares de l'Epoque Almohade: Frontispices et Unwans''. Estudios Arabes e Islamicos. p. 72-74. Most Qur'anic manuscripts were close to square-shaped, though other religious texts were typically vertically oriented. With the exception of a few large-scale Qur'ans, most were modestly sized, ranging from 11 centimenters to 22 centimeters on each side, with 19 to 27 lines of script each page. In contrast, large-sized Qur'ans were typically approximately 60 centimeters by 53 centimeters and had an average of five to nine lines of script to a page, typically in Maghrebi thuluth.