Alexander Pentland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander Augustus Norman Dudley "Jerry" Pentland, (5 August 1894 – 3 November 1983) was an Australian

On 20 July 1917, soon after arriving at his new unit in France, Pentland achieved his first victory in the SPAD when he shared in the destruction of an

On 20 July 1917, soon after arriving at his new unit in France, Pentland achieved his first victory in the SPAD when he shared in the destruction of an  Credited with one more victory during August 1917, and another four the following month, Pentland's score stood at ten when he was injured on 26 September after an artillery shell struck his SPAD and forced him to crash land. Following his recovery, he again spent time instructing before being posted back to a front-line unit, this time No. 87 Squadron, operating

Credited with one more victory during August 1917, and another four the following month, Pentland's score stood at ten when he was injured on 26 September after an artillery shell struck his SPAD and forced him to crash land. Following his recovery, he again spent time instructing before being posted back to a front-line unit, this time No. 87 Squadron, operating

In 1927, Pentland formed Mandated Territory Airways with entrepreneur Albert Royal to fly freight to and from the goldfields of New Guinea. The pair bought a DH.60 Moth biplane, which Pentland ferried to the firm's base at

In 1927, Pentland formed Mandated Territory Airways with entrepreneur Albert Royal to fly freight to and from the goldfields of New Guinea. The pair bought a DH.60 Moth biplane, which Pentland ferried to the firm's base at

Having offered his services to the Australian government on his return from New Guinea, Pentland rejoined the RAAF on 17 June 1940. He undertook the flying instructors' course at

Having offered his services to the Australian government on his return from New Guinea, Pentland rejoined the RAAF on 17 June 1940. He undertook the flying instructors' course at

''Royal Australian Air Force'', p. 634

Its inventory included such types as the

fighter ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

in World War I. Born in Maitland, New South Wales, he commenced service as a Lighthorseman with the Australian Imperial Force in 1915, and saw action at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

. He transferred to the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

the following year, rising to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. Credited with twenty-three aerial victories, Pentland became the fifth highest-scoring Australian ace of the war, after Robert Little, Stan Dallas, Harry Cobby

Air Commodore Arthur Henry Cobby, (26 August 1894 – 11 November 1955) was an Australian air force, military aviator. He was the leading flying ace, fighter ace of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) during World War I, despite seeing acti ...

and Roy King. He was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

in January 1918 for "conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty" on a mission attacking an aerodrome behind enemy lines, and the Distinguished Flying Cross that August for engaging four hostile aircraft single-handedly.

Pentland served in the fledgling Royal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal Air force, aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the Governor-Gener ...

(RAAF), and later the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, before going into business in 1927. His ventures included commercial flying around the goldfields of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

, aircraft design and manufacture, flight instruction, and charter work. In the early 1930s, he was employed as a pilot with Australian National Airways

Australian National Airways (ANA) was Australia's predominant aerial carrier from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s.

The Holyman's Airways period

On 19 March 1932 Flinders Island Airways began a regular aerial service using the Desoutter Mk.I ...

, and also spent time as a dairy farmer. Soon after the outbreak of World War II, he re-enlisted in the RAAF, attaining the rank of squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr or S/L) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Squadron leader is immediatel ...

and commanding rescue and communications units in the South West Pacific

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

. Perhaps the oldest operational pilot in the wartime RAAF, Pentland was responsible for rescuing airmen, soldiers and civilians, and earned the Air Force Cross for his "outstanding courage, initiative and skill". He became a trader in New Guinea when the war ended in 1945, and later a coffee planter. Retiring in 1959, he died in 1983 at the age of eighty-nine.

Early life

Alexander Augustus Norman Dudley Pentland was born in Maitland, New South Wales, on 5 August 1894.Newton, ''Australian Air Aces'', pp. 52–53 His father Alexander was Irish, and his mother Annie Norma (née Farquhar) was Scottish. Educated at The King's School, Sydney, andBrighton Grammar

Brighton Grammar School is a private Anglican day school for boys, located in Brighton, a south-eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Founded in 1882 by George Henry Crowther, Brighton Grammar has a non-selective enrolment policy ...

, Melbourne, Pentland went on to study dairy farming at Hawkesbury Agricultural College

Hawkesbury Agricultural College was the first agricultural college in New South Wales, Australia, based in Richmond. It operated from 1891 to 1989.

History

It was established on 10 March 1891, and formally opened by Minister for Mines and Agric ...

, and later worked as a jackaroo.Schaedel, ''Australian Air Ace'', p. 13 His father was a physician who joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I and served as a major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in the Australian Army Medical Corps

The Royal Australian Army Medical Corps (RAAMC) is the branch of the Australian Army responsible for providing medical care to Army personnel. The AAMC was formed in 1902 through the amalgamation of medical units of the various Australian colon ...

.

World War I

Pentland enlisted as aprivate

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

in the AIF on 5 March 1915, sailing for Egypt with the 12th Light Horse Regiment aboard HMAT A29 ''Suevic'' on 13 June. In August, his unit deployed to Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

, where he fought as a machine gunner before being hospitalised the following month, suffering from typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

; he was evacuated to England in December.Garrisson, ''Australian Fighter Aces'', p. 98 Determined to leave the trenches behind after recovering, he volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

(RFC) and was discharged from the AIF on 21 February 1916 to take up his commission as a temporary second lieutenant in the RFC.Schaedel, ''Australian Air Ace'', pp. 15–17 His first solo flight in a Maurice Farman Longhorn at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

, after two hours of dual instruction, ended with him overshooting the runway and crashing in a sewage farm, but he was unhurt and immediately undertook a second solo attempt, landing successfully. It was at Brooklands that he was first nicknamed "Jerry". After completing pilot training, he was posted to France in June, flying B.E.2s with No. 16 Squadron. Though the slow and vulnerable B.E.2 was considered " Fokker fodder" by its crews, Pentland and his observer quickly managed to score the former's first aerial victory, bringing down a German ''Eindecker'' over Habourdin on 9 June.Guttman, ''SPAD VII Aces of World War 1'', pp. 42–45 He was then posted to No. 29 Squadron and was converting to DH.2 "pusher" fighters when he broke his leg playing rugby. After recovering, he instructed at London Colney

London Colney () is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Hertfordshire, England. It is located to the north of London, close to Junction 22 of the M25 motorway.

It is around south-east of St Albans city centre (and within ...

until June 1917, when he joined No. 19 Squadron, flying SPAD S.VIIs. This would become Pentland's favourite type due to its strength and manoeuvrability, even though it had to be 'flown' constantly and was unforgiving at low speed.

On 20 July 1917, soon after arriving at his new unit in France, Pentland achieved his first victory in the SPAD when he shared in the destruction of an

On 20 July 1917, soon after arriving at his new unit in France, Pentland achieved his first victory in the SPAD when he shared in the destruction of an Albatros

An albatross is one of a family of large winged seabirds.

Albatross or Albatros may also refer to:

Animals

* Albatross (butterfly) or ''Appias'', a genus of butterfly

* Albatross (horse) (1968–1998), a Standardbred horse

Literature

* Albat ...

two-seater. He followed this up with a solo "kill" on 12 August. Four days later, after stopping an enemy truck convoy in its tracks by crippling its lead vehicle with machine-gun fire, he reportedly engaged ten Albatros fighters single-handedly; by the time he had driven them off, four bullets had penetrated his leather flying suit without injuring him, and his plane had absorbed so much punishment that it had to be scrapped when he got back to base. After sharing another Albatros two-seater on 20 August, Pentland led a raid on Marcke aerodrome, home of Baron von Richthofen's ''Jasta'' 11, on 26 August. On the way, he helped bring down a DFW C.V, then achieved complete surprise at the airfield, which he and his flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

proceeded to shoot up. On the return journey, he strafed an enemy train until his guns jammed and then, having managed to clear them, engaged two more German scouts. His part in the raid earned him the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

, promulgated in ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'', known generally as ''The Gazette'', is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, i ...

'' on 9 January 1918:

Credited with one more victory during August 1917, and another four the following month, Pentland's score stood at ten when he was injured on 26 September after an artillery shell struck his SPAD and forced him to crash land. Following his recovery, he again spent time instructing before being posted back to a front-line unit, this time No. 87 Squadron, operating

Credited with one more victory during August 1917, and another four the following month, Pentland's score stood at ten when he was injured on 26 September after an artillery shell struck his SPAD and forced him to crash land. Following his recovery, he again spent time instructing before being posted back to a front-line unit, this time No. 87 Squadron, operating Sopwith Dolphin

The Sopwith 5F.1 Dolphin was a British fighter aircraft manufactured by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It was used by the Royal Flying Corps and its successor, the Royal Air Force, during the First World War. The Dolphin entered service on the ...

s. Promoted captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

, he returned to France in April 1918, having transferred the same month with the rest of the RFC to the newly formed Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF).Schaedel, ''Australian Air Ace'', pp. 51–56 Pentland went on to achieve thirteen victories with No. 87 Squadron, where his aggressive tactics saw him dubbed the "Wild Australian" by colleagues. Appointed commander of 'B' Flight, he also frequently acted as a "lone wolf", actively seeking dogfights with enemy aircraft on his own.Franks, ''Dolphin and Snipe Aces of World War 1'', pp. 53–54 On 18 June, he was alone on patrol when he engaged a flight of four Rumpler

Rumpler-Luftfahrzeugbau GmbH, Rumpler-Werke, usually known simply as Rumpler was a German aircraft and automobile manufacturer.

History

Founded in Berlin by Austrian engineer Edmund Rumpler in 1909 as Rumpler Luftfahrzeugbau.Gunston 1993, p. ...

high-altitude reconnaissance

In military operations, military reconnaissance () or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, the terrain, and civil activities in the area of operations. In military jargon, reconnai ...

aircraft, forcing down three of them. This action earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, gazetted on 3 August:

On 25 August, Pentland attacked and destroyed two German planes, a DFW two-seater and Fokker D.VII

The Fokker D.VII is a German World War I fighter aircraft designed by Reinhold Platz of the '' Fokker-Flugzeugwerke''. Germany produced around 3,300 D.VII aircraft in the second half of 1918. In service with the ''Luftstreitkräfte'', the D.VII ...

, before himself being shot down and wounded in the foot. These would be his last victories; his grand total of twenty-three included eleven destroyed, one of which was shared, and twelve out of control, three of them shared. This score ranked him fifth among the Australian aces of the war after Robert Little, Stan Dallas, Harry Cobby

Air Commodore Arthur Henry Cobby, (26 August 1894 – 11 November 1955) was an Australian air force, military aviator. He was the leading flying ace, fighter ace of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) during World War I, despite seeing acti ...

and Roy King.

Interwar period

Pentland relinquished his RAF commission and returned to Australia at the end of the war, earning money by giving joyrides in an Avro 504K. Looking for a more secure future, he joined the newly establishedRoyal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal Air force, aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the Governor-Gener ...

(RAAF) in August 1921, following an interview with Wing Commander Stanley Goble

Air Vice Marshal Stanley James (Jimmy) Goble, CBE, DSO, DSC (21 August 1891 – 24 July 1948) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He served three terms as Chief of the Air Staff, alternating with Wing Comm ...

, a wartime acquaintance through the RAF. Ranked flight lieutenant, Pentland was put in charge of the RAAF's complement of S.E.5

The Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 is a British biplane fighter aircraft of the First World War. It was developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory by a team consisting of Henry Folland, John Kenworthy and Major Frank Goodden. It was one of the ...

fighters at Point Cook

Point Cook is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, south-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Wyndham local government area. Point Cook recorded a population of 66,781 at the 2021 census, making it t ...

, Victoria, part of the Imperial Gift recently donated by Great Britain. The young Air Force had the atmosphere of a flying club, where everyone knew everyone else. Tensions sometimes arose between those who had served with British forces during the war, and those who had belonged to the Australian Flying Corps

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was the branch of the Australian Army responsible for operating aircraft during World War I, and the forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The AFC was established in 1912, though it was not until ...

(AFC); the former considered that they were discriminated against when it came to filling senior positions, and came the day Pentland and fellow ex-RAF member Hippolyte De La Rue threw an "uppity" AFC man into a mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

fireplace. Deciding that his RAAF career was not progressing, Pentland applied for a short-service commission as a flying officer

Flying officer (Fg Offr or F/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Flying officer is immediately ...

with the RAF in 1923, which was granted as of 23 April.Schaedel, ''Australian Air Ace'', pp. 73–77 He journeyed to Britain with new wife Madge (née Moffat), whom he married on 5 March, just before departing Australia; they had one daughter, Carleen, the following year. Pentland completed the course at Central Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school in the world. The sch ...

, Uphavon, and became an instructor there, gaining promotion to flight lieutenant before leaving the RAF on 20 July 1926 and returning to Australia.

In 1927, Pentland formed Mandated Territory Airways with entrepreneur Albert Royal to fly freight to and from the goldfields of New Guinea. The pair bought a DH.60 Moth biplane, which Pentland ferried to the firm's base at

In 1927, Pentland formed Mandated Territory Airways with entrepreneur Albert Royal to fly freight to and from the goldfields of New Guinea. The pair bought a DH.60 Moth biplane, which Pentland ferried to the firm's base at Lae

Lae (, , later ) is the capital of Morobe Province and is the second-largest city in Papua New Guinea. It is located near the delta of the Markham River on the northern coast of Huon Gulf. It is at the start of the Highlands Highway, which is ...

in February 1928. The business prospered in the short term, to the extent that the partners took on another Moth and more pilots. By the end of the year, Pentland was suffering from malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and had to abandon the venture, selling one of the planes to Guinea Airways and returning to Australia with the other. After recovering in the new year, he embarked on a series of new enterprises, including aircraft manufacture, a flying school, and charter work. In February 1929, he formed the General Aircraft Company with Royal and another partner to produce an Australian-designed aeroplane, the Genairco, of which eight were eventually sold. With the Moth from Mandated Territory Airways, he established Pentland's Flying School at Mascot

A mascot is any human, animal, or object thought to bring luck, or anything used to represent a group with a common public identity, such as a school, sports team, university society, society, military unit, or brand, brand name. Mascots are als ...

, New South Wales. He also flew charters with a Moth owned by ''The Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot Plasma (physics), plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as ...

'' newspaper, using the same aircraft that September to compete in the East-West Air Race from Sydney to Perth, as part of the celebrations for the Western Australia Centenary

In 1929, Western Australia (WA) celebrated the centenary of the founding of Perth and the establishment of the Swan River Colony, the first permanent European settlement in WA. A variety of events were run in Perth, regional areas throughout the ...

. The event attracted several veteran aviators of World War I, including Horrie Miller—the eventual winner on handicap—and Charles "Moth" Eaton, whom Pentland beat into fifth place across the line.

Lack of patronage led to Pentland folding his businesses and taking a job in 1930 as a pilot with Australian National Airways

Australian National Airways (ANA) was Australia's predominant aerial carrier from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s.

The Holyman's Airways period

On 19 March 1932 Flinders Island Airways began a regular aerial service using the Desoutter Mk.I ...

(ANA), a new airline founded by Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was ...

and Charles Ulm

Charles Thomas Philippe Ulm (18 October 1898 – 3 December 1934) was a pioneer Australian aviator. He partnered with Charles Kingsford Smith in achieving a number of aviation firsts, serving as Kingsford Smith's co-pilot on the first transpaci ...

. By 1932, ANA was in trouble as well, and Pentland left to set up as a dairy farmer on a property he bought at Singleton

Singleton may refer to:

Sciences, technology Mathematics

* Singleton (mathematics), a set with exactly one element

* Singleton field, used in conformal field theory Computing

* Singleton pattern, a design pattern that allows only one instance ...

. Within two years, drought forced him to sell the land and he returned to earning his living as a pilot, instructing at aero clubs in Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

and New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

. By late 1937, he was again employed as a transport pilot in New Guinea, where he was known as a practical joker who liked to hold a map in front of his face in apparent short-sightedness and ask his passengers if they could see a landing ground anywhere. He returned to Australia after war was declared in September 1939.

World War II

Having offered his services to the Australian government on his return from New Guinea, Pentland rejoined the RAAF on 17 June 1940. He undertook the flying instructors' course at

Having offered his services to the Australian government on his return from New Guinea, Pentland rejoined the RAAF on 17 June 1940. He undertook the flying instructors' course at Central Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school in the world. The sch ...

in Camden, New South Wales, and was posted as an instructor to elementary flying training schools in eastern Australia, including Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

, Tamworth, Temora, Bundaberg

Bundaberg () is the major regional city in the Wide Bay-Burnett region of the state of Queensland, Australia. It is the List of cities in Australia by population, ninth largest city in the state. The Bundaberg central business district is situa ...

, and Lowood. Addressed by a young pilot at one school as "Pop", Pentland responded in front of the large audience, "I'm sorry son, but I don't remember sleeping with your mother". He was promoted to flight lieutenant in October 1941, and joined No. 1 Communication Flight in June 1942. Based in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

at Laverton and, later, Essendon Essendon may refer to:

Australia

*Essendon, Victoria

**Essendon railway station

**Essendon Airport

*Essendon Football Club, in the Australian Football League

*Electoral district of Essendon

*Electoral district of Essendon and Flemington

United Kin ...

, it was primarily engaged in army and naval cooperation, and operated as far afield as the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

and New Guinea.

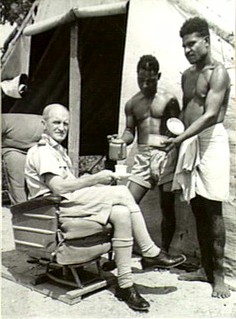

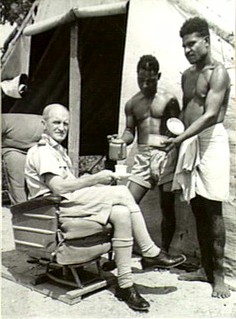

Promoted to squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr or S/L) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Squadron leader is immediatel ...

, in November 1942 Pentland was posted to Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New ...

, New Guinea, as commanding officer (CO) of No. 1 Rescue and Communication Squadron, better known as "Pentland's Flying Circus".RAAF Historical Section, ''Units of the Royal Australian Air Force'', p. 186 The official history of Australia in the war described this as the RAAF's "most unusual operational unit", asserting that its "strange assortment of light aircraft was as varied and as appropriate to its task as was the flying record of its commander ...".Gillison''Royal Australian Air Force'', p. 634

Its inventory included such types as the

de Havilland Tiger Moth

The de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth is a 1930s British biplane designed by Geoffrey de Havilland and built by the de Havilland, de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other operators as a primary traine ...

, DH.84 Dragon, Fox Moth

''Macrothylacia rubi'', the fox moth, is a lepidopteran belonging to the family Lasiocampidae. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae''.

Distribution and habitat

This species can be found from We ...

, Dragon Rapide, and Avro Anson

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engine, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), R ...

. Perhaps the RAAF's oldest pilot in any theatre of operations, Pentland was responsible for the rescue of downed US airmen, as well as the evacuation of civilians and soldiers. He also organised aerial surveys around Daru

Daru is the capital of the Western Province of Papua New Guinea and a former Catholic bishopric. Daru town falls under the jurisdiction of Daru Urban LLG.

The township is entirely located on an island that goes by the same name, which is lo ...

and Milne Bay

Milne Bay is a large bay in Milne Bay Province, south-eastern Papua New Guinea. More than long and over wide, Milne Bay is a sheltered deep-water harbor accessible via Ward Hunt Strait. It is surrounded by the heavily wooded Stirling Range (Papu ...

, developing new bases and emergency airfields at locales such as Bena Bena Benabena, also known as Bena Bena, is a stretch of valley that extends to the east of Goroka town in the west and borders with the Upper Ramu area of Madang Province to the north, Ungaii District to its south and Henganofi District to its east. The ...

, Abau, Kulpi, and Port Moresby.

Posted back to Australia after relinquishing command of No. 1 Rescue and Communication Squadron in June 1943, Pentland received radar training and helped to set up the RAAF's early warning grid in northern Australia. He returned to New Guinea in March 1944 as CO of No. 8 Communication Unit, Goodenough Island

Goodenough Island in the Solomon Sea, also known as Nidula Island, is the westernmost of the three large islands of the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. It lies to the east of mainland New Guinea and southwest ...

, which had been formed in November 1943 from Pentland's old Rescue and Communications Squadron. Operating Tiger Moth, Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus is a British single-engine Amphibious aircraft, amphibious biplane designed by Supermarine's R. J. Mitchell. Primarily used as a maritime patrol aircraft, it was the first British Squadron (aviation), squadron-service ai ...

, Consolidated PBY Catalina

The Consolidated Model 28, more commonly known as the PBY Catalina (U.S. Navy designation), is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft designed by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. In U.S. Army service, it was designated as the OA- ...

, Dornier Do 24, Bristol Beaufort

The Bristol Beaufort (manufacturer designation Type 152) is a British twin-engined torpedo bomber designed by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, and developed from experience gained designing and building the earlier Bristol Blenheim, Blenheim li ...

, CAC Boomerang

The CAC Boomerang is a fighter aircraft designed and manufactured in Australia by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation between 1942 and 1945. Approved for production shortly following the Empire of Japan's entry into the Second World War, the ...

, Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufor ...

, and Vultee Vengeance

The Vultee A-31 Vengeance is an American dive bomber of World War II that was built by Vultee Aircraft. A modified version was called A-35. The Vengeance was not used operationally by the United States but was operated as a front-line aircraft ...

aircraft, the unit performed reconnaissance and bombing sorties over New Britain and north-eastern New Guinea, as well as rescue and survey missions. In July 1945, Pentland was posted to Mascot as CO of No. 3 Communication Unit, serving until September. His achievements in New Guinea earned him the Air Force Cross, the citation being promulgated on 22 February 1946 and concluding:

Later life

With the end of hostilities in the Pacific, Pentland was discharged from the RAAF on 2 November 1945. He took the opportunity to purchase surplus military equipment in New Guinea and established himself as a trader inFinschhafen

Finschhafen is a town east of Lae on the Huon Peninsula in Morobe Province of Papua New Guinea. The town is commonly misspelt as Finschafen or Finschaven. During World War II, the town was also referred to as Fitch Haven in the logs of some U. ...

, later expanding to Lae and Wau

Wau may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

Papua New Guinea

* Wau, Papua New Guinea

* Wau Airport (Papua New Guinea)

* Wau Rural LLG, (local level government)

South Sudan

* Wau State, South Sudan

* Wau, South Sudan, city

* Wau railway s ...

. In 1948, he went into business as a coffee planter in Goroka

Goroka is the capital of the Eastern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea. It is a town of approximately 19,000 people (2000), above sea level. It has an airport (in the centre of town) and is on the " Highlands Highway", about from Lae in Mor ...

, and also recruited labour from the highlands for industries on the coast. Prospering as a planter, he contributed to development of the region by building Goroka's original constant-flowing water supply and encouraging other businesses to set up there. His ongoing commitments in New Guinea meant that he was not invested

Investment is traditionally defined as the "commitment of resources into something expected to gain value over time". If an investment involves money, then it can be defined as a "commitment of money to receive more money later". From a broade ...

with his Air Force Cross until 1950. In 1959, he sold his interests in Goroka and retired with Madge to their seaside home in Bayview, New South Wales.Schaedel, ''Australian Air Ace'', pp. 153–157 Madge Pentland died in 1982, and Jerry eighteen months later, on 3 November 1983, at the War Veterans Home in Collaroy Collaroy may refer to:

*Collaroy Plateau

Collaroy Plateau is a suburb of northern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Collaroy Plateau is 22 kilometres north-east of the Sydney central business district, in the Local govern ...

. He was survived by daughter Carleen, and cremated on 7 November.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pentland, Jerry 1894 births 1983 deaths Australian Army soldiers Australian recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Australian World War I flying aces Australian commercial aviators Military personnel from New South Wales Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Air Force officers Royal Air Force personnel of World War I Royal Australian Air Force officers Royal Australian Air Force personnel of World War II Royal Flying Corps officers