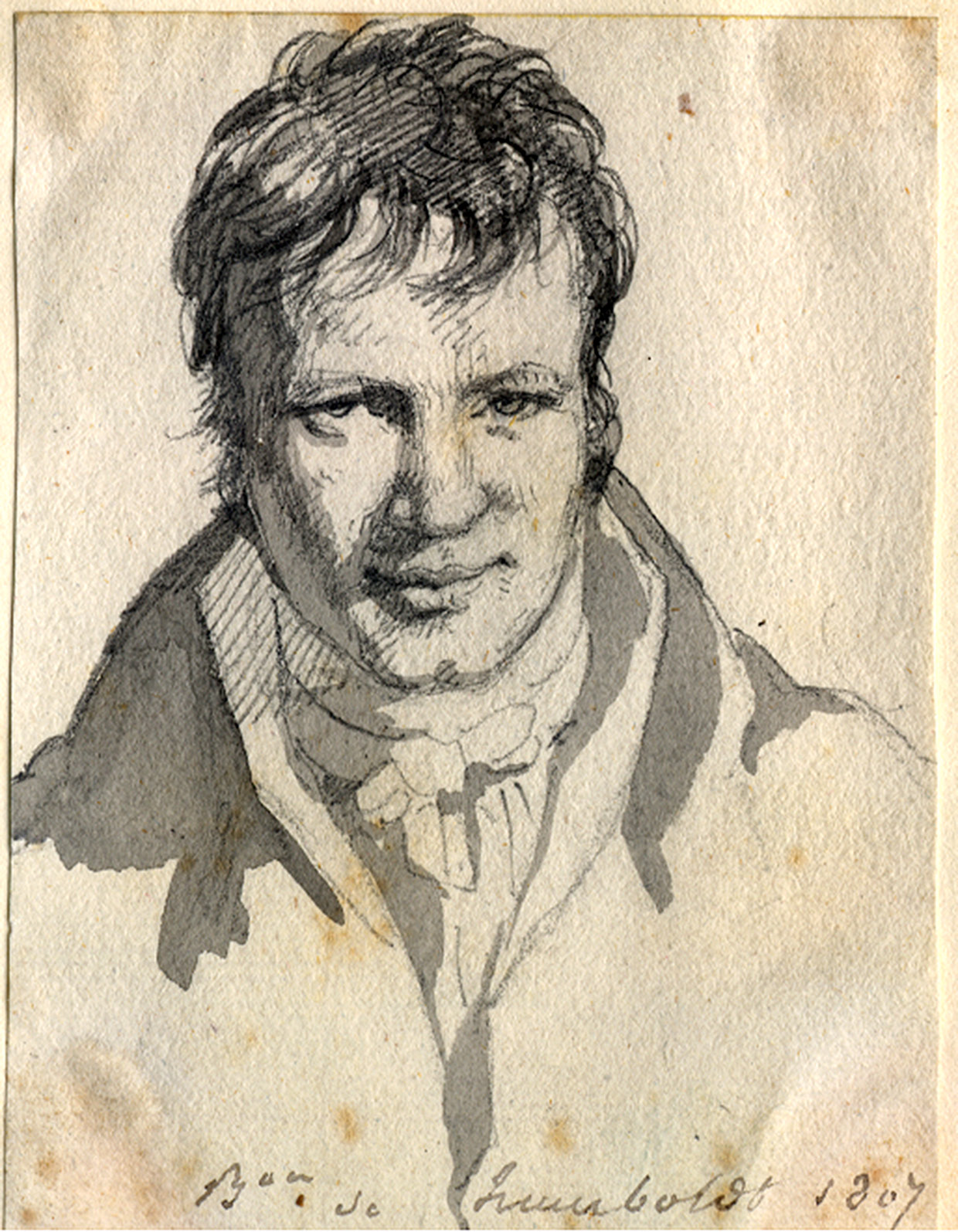

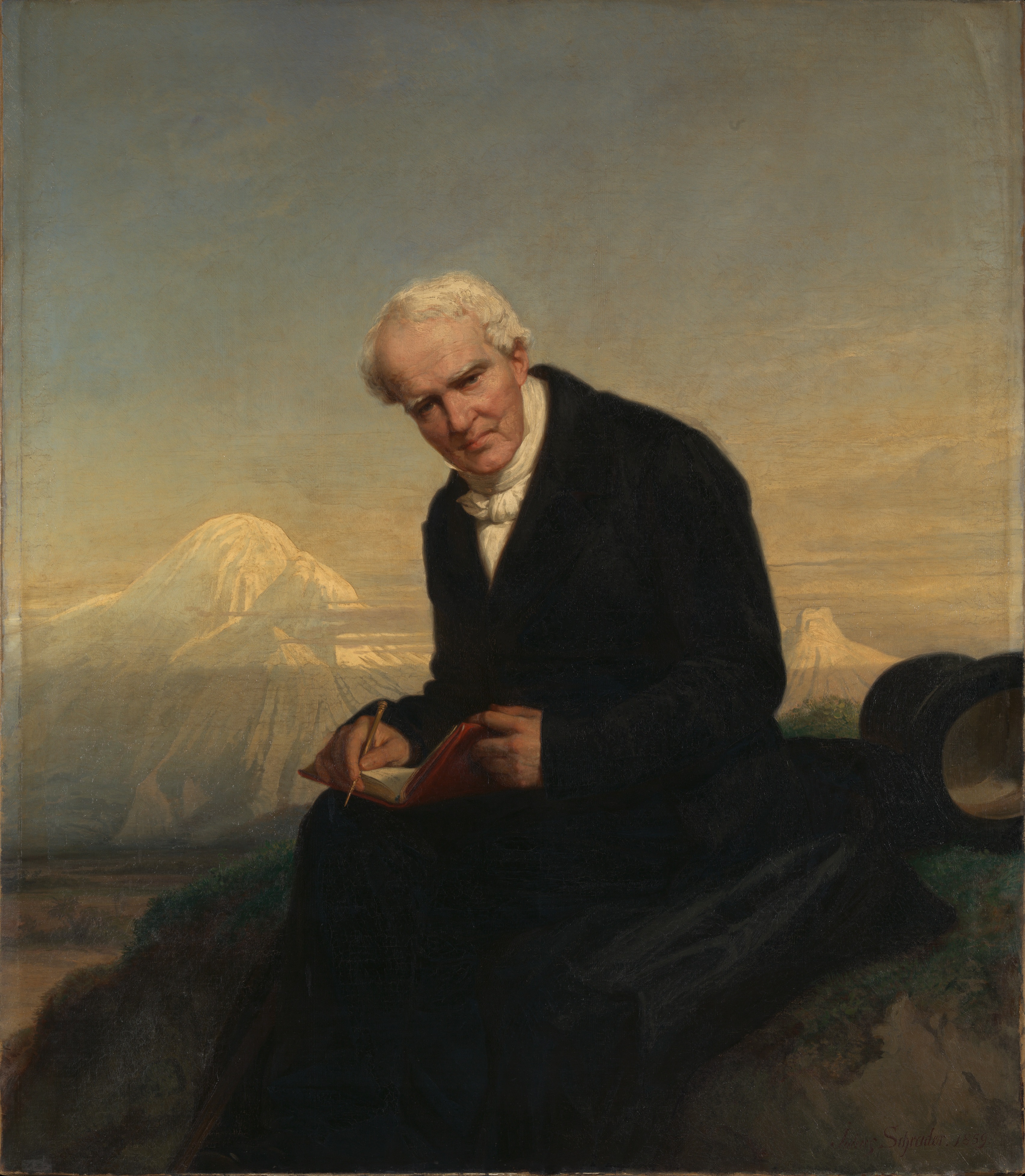

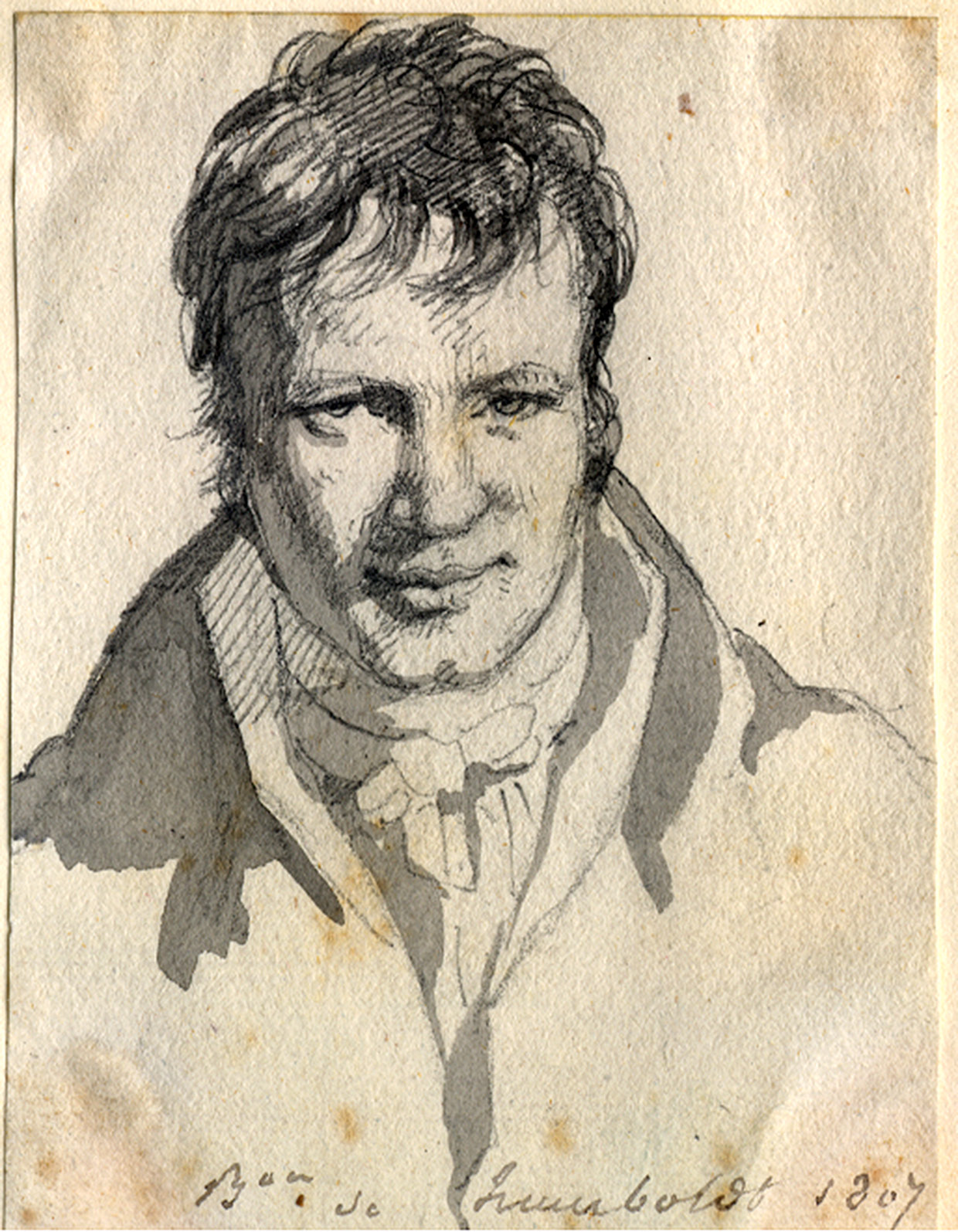

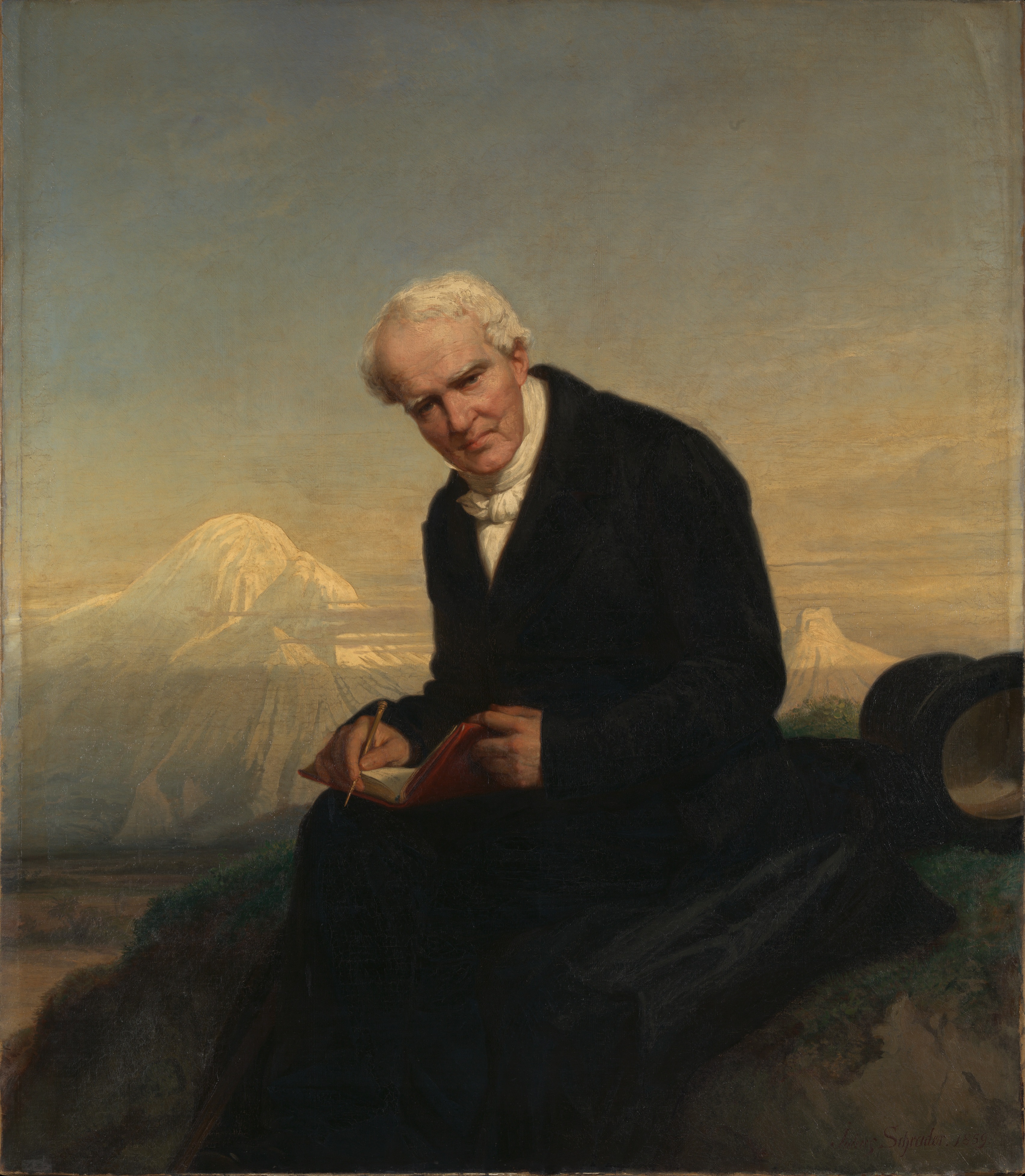

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was a German

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

,

geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

,

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

,

explorer

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

, and proponent of

Romantic philosophy and

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher, and

linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a German philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1949, the university was named aft ...

(1767–1835). Humboldt's quantitative work on

botanical

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

laid the foundation for the field of

biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

, while his advocacy of long-term systematic geophysical measurement pioneered modern

geomagnetic

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from structure of Earth, Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from ...

and

meteorological

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agriculture ...

monitoring. Humboldt and

Carl Ritter

Carl Ritter (August 7, 1779September 28, 1859) was a German geographer. Along with Alexander von Humboldt, he is considered one of the founders of modern geography, as they established it as an independent scientific discipline. From 1825 until ...

are both regarded as the founders of modern geography as they established it as an independent scientific discipline.

Between 1799 and 1804, Humboldt travelled extensively in the

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, exploring and describing them for the first time from a non-Spanish European scientific point of view. His description of the journey was written up and published in several volumes over 21 years.

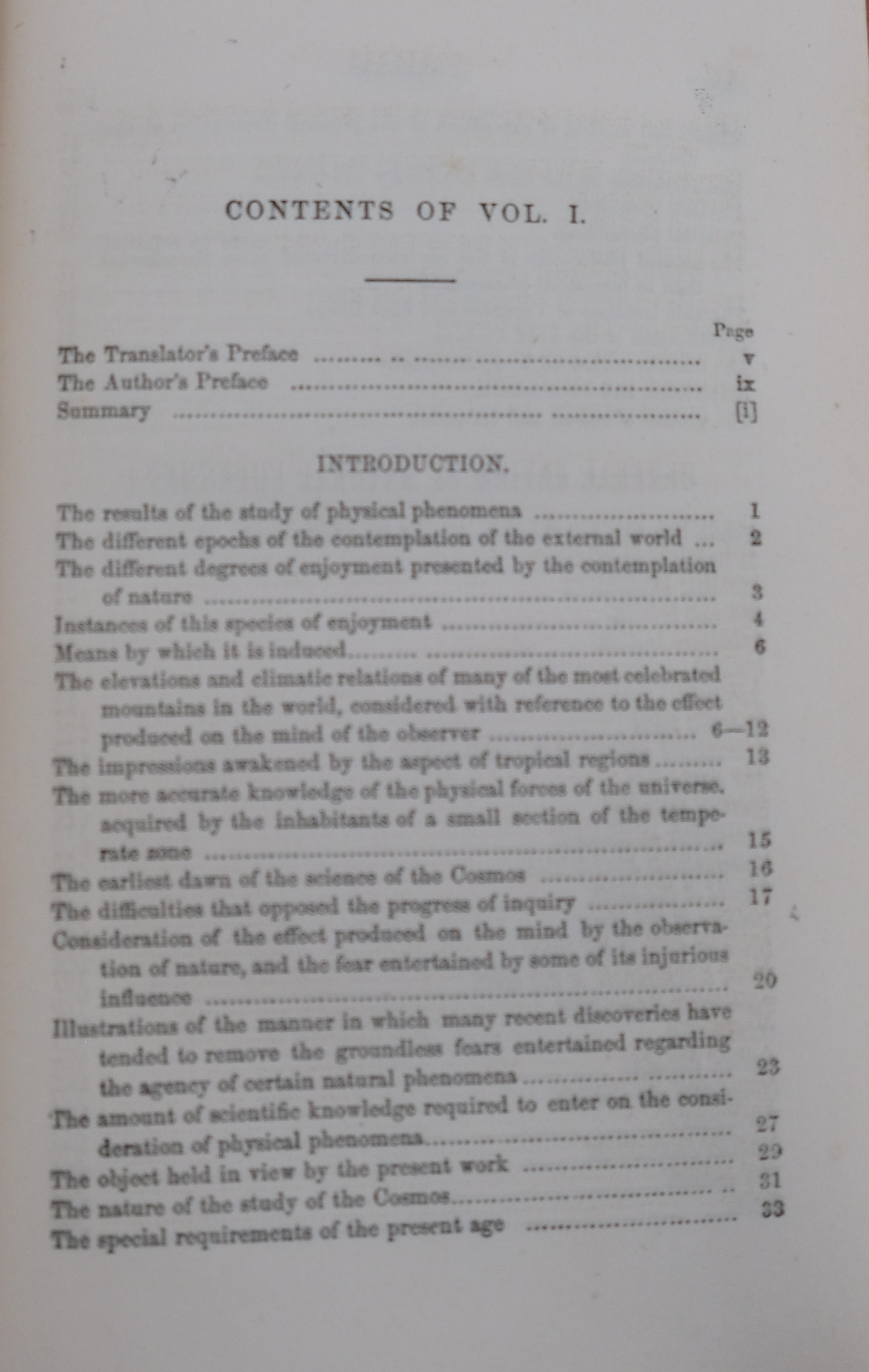

Humboldt resurrected the use of the word ''cosmos'' from the ancient Greek and assigned it to his multivolume treatise, ''

Kosmos

Cosmos generally refers to an orderly or harmonious system.

Cosmos or Kosmos may also refer to:

Space

* ''Cosmos 1'', a privately funded solar sail spacecraft project

* Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS), a Hubble Space Telescope Treasury Project

...

'', in which he sought to unify diverse branches of scientific knowledge and culture. This important work also motivated a holistic perception of the universe as one interacting entity,

which introduced concepts of

ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

leading to ideas of

environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

. In 1800, and again in 1831, he described scientifically, on the basis of observations generated during his travels, local impacts of development causing

human-induced climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes ...

.

Humboldt is seen as "the father of ecology" and "the father of environmentalism".

Early life, family and education

Alexander von Humboldt was born in Berlin in

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

on 14 September 1769.

He was baptized as a baby in the Lutheran faith, with the

Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ...

serving as godfather.

His father, Alexander Georg von Humboldt (1720-1779), belonged to a prominent

German noble family from

Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

. Although not one of the titled gentry, he was a major in the

Prussian Army, who had served with the

Duke of Brunswick

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they a ...

. At age 42, Alexander Georg was rewarded for his services in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

with the post of royal

chamberlain.

He profited from the contract to lease state lotteries and tobacco sales.

Alexander's grandfather was Johann Paul von Humboldt (1684-1740), who married Sophia Dorothea von Schweder (1688-1749), daughter of Prussian General Adjutant Michael von Schweder (1663-1729).

In 1766, his father, Alexander Georg married

Maria Elisabeth Colomb, a well-educated woman and widow of Baron Friedrich Ernst von Holwede (1723-1765), with whom she had a son Heinrich Friedrich Ludwig (1762-1817). Alexander Georg and Maria Elisabeth had four children: two daughters, Karoline and Gabriele, who died young, and then two sons, Wilhelm and Alexander. Her first-born son, Wilhelm and Alexander's half-brother,

Rittmaster

Rittmaster () is usually a commissioned officer military rank used in a few armies, usually equivalent to Captain. Historically it has been used in Germany, Austria-Hungary, Scandinavia, and some other countries.

A is typically in charge of a s ...

in the

Gendarme regiment was something of a ne'er do well, not often mentioned in the family history.

Alexander Georg died in 1779, leaving the brothers Humboldt in the care of their emotionally distant mother. She had high ambitions for Alexander and his older brother Wilhelm, hiring excellent tutors, who were

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

thinkers, including Kantian physician

Marcus Herz and botanist

Carl Ludwig Willdenow

Carl Ludwig Willdenow (22 August 1765 – 10 July 1812) was a German botanist, pharmacist, and plant Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist. He is considered one of the founders of phytogeography, the study of the geographic distribution of plants. ...

, who became one of the most important botanists in Germany. Humboldt's mother expected them to become civil servants of the Prussian state. The money left to Alexander's mother by Baron Holwede became instrumental in funding Alexander's explorations after her death; contributing more than 70% of his private income.

Due to his youthful penchant for collecting and labeling plants, shells, and insects, Alexander received the playful title of "the little apothecary".

Marked for a political career, Alexander studied

finance

Finance refers to monetary resources and to the study and Academic discipline, discipline of money, currency, assets and Liability (financial accounting), liabilities. As a subject of study, is a field of Business administration, Business Admin ...

for six months in 1787 at the

University of Frankfurt (Oder)

European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder) () is a university located at Frankfurt (Oder) in Brandenburg, Germany. It is also known as the University of Frankfurt (Oder). The city is on the Oder River, which marks the border between Germany ...

, which his mother might have chosen less for its academic excellence than its closeness to their home in Berlin. On 25 April 1789, he matriculated at the

University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

, then known for the lectures of

C. G. Heyne and anatomist

J. F. Blumenbach. His brother Wilhelm was already a student at Göttingen, but they did not interact much, since their intellectual interests were quite different. His vast and varied interests were by this time fully developed.

At the University of Göttingen, Humboldt met Steven Jan van Geuns, a Dutch medical student, with whom he travelled to the

Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

in the fall of 1789. In Mainz, they met

Georg Forster

Johann George Adam Forster, also known as Georg Forster (; 27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German geography, geographer, natural history, naturalist, ethnology, ethnologist, travel literature, travel writer, journalist and revol ...

, a naturalist who had been with Captain

James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

on his second voyage. Humboldt's scientific excursion resulted in his 1790 treatise ''Mineralogische Beobachtungen über einige Basalte am Rhein'' (Brunswick, 1790) (''Mineralogic Observations on Several Basalts on the River Rhine''). The following year, 1790, Humboldt returned to Mainz to embark with Forster on a journey to England, Humboldt's first sea voyage, the Netherlands, and France. In England, he met Sir

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, president of the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, who had travelled with Captain Cook; Banks showed Humboldt his huge herbarium, with specimens of the South Sea tropics. The scientific friendship between Banks and Humboldt lasted until Banks's death in 1820, and the two shared botanical specimens for study. Banks also mobilized his scientific contacts in later years to aid Humboldt's work. In Paris, Humboldt and Forster witnessed the preparations for the

Festival of the Federation. Yet, Humboldt's take on the French Revolution remained ambivalent.

Humboldt's passion for travel was of long standing. He devoted to prepare himself as a scientific explorer. With this emphasis, he studied commerce and foreign languages at

Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, geology at

Freiberg School of Mines in 1791 under

A.G. Werner, leader of the

Neptunist school of geology; from anatomy at

Jena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

under

J.C. Loder; and astronomy and the use of scientific instruments under

F.X. von Zach and

J.G. Köhler.

At Freiberg, he met a number of men who were to prove important to him in his later career, including Spaniard Manuel del Río, who became director of the School of Mines the crown established in Mexico;

Christian Leopold von Buch

Christian Leopold von Buch (26 April 1774 – 4 March 1853), usually cited as Leopold von Buch, was a German geologist and paleontologist born in Stolpe an der Oder (now a part of Angermünde, Brandenburg) and is remembered as one of the mos ...

, who became a regional geologist; and, most importantly, , who became Humboldt's tutor and close friend. During this period, his brother Wilhelm married, but Alexander did not attend the nuptials.

Travels and work in Europe

Humboldt graduated from the Freiberg School of Mines in 1792 and was appointed to a

Prussian government

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

position in the Department of Mines as an inspector in

Bayreuth

Bayreuth ( or ; High Franconian German, Upper Franconian: Bareid, ) is a Town#Germany, town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtel Mountains. The town's roots date back to 11 ...

and the

Fichtel Mountains

The Fichtel Mountains (, ; ) is a mountain range in Germany and the Czech Republic. They extend from the valley of the Red Main River in northeastern Bavaria to the Karlovy Vary Region in western Czech Republic. The Fichtel Mountains contain an ...

. Humboldt was excellent at his job, with production of gold ore in his first year outstripping the previous eight years. During his period as a mine inspector, Humboldt demonstrated his deep concern for the men laboring in the mines. He opened a free school for miners, paid for out of his own pocket, which became an unchartered government training school for labor. He also sought to establish an emergency relief fund for miners, aiding them following accidents.

Humboldt's researches into the vegetation of the mines of

Freiberg

Freiberg () is a university and former mining town in Saxony, Germany, with around 41,000 inhabitants. The city lies in the foreland of the Ore Mountains, in the Saxon urbanization axis, which runs along the northern edge of the Elster and ...

led to the publication in Latin (1793) of his ''Florae Fribergensis, accedunt Aphorismi ex Doctrina, Physiologiae Chemicae Plantarum'', which was a compendium of his botanical researches. That publication brought him to the attention of

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, who had met Humboldt at the family home when Alexander was a boy, but Goethe was now interested in meeting the young scientist to discuss metamorphism of plants. An introduction was arranged by Humboldt's brother, who lived in the university town of Jena, not far from Goethe. Goethe had developed his own extensive theories on comparative anatomy. Working before Darwin, he believed that animals had an internal force, an ''urform'', that gave them a basic shape and then they were further adapted to their environment by an external force. Humboldt urged him to publish his theories. Together, the two discussed and expanded these ideas. Goethe and Humboldt soon became close friends.

Humboldt often returned to Jena in the years that followed. Goethe remarked about Humboldt to friends that he had never met anyone so versatile. Humboldt's drive served as an inspiration for Goethe. In 1797, Humboldt returned to Jena for three months. During this time, Goethe moved from his residence in Weimar to reside in Jena. Together, Humboldt and Goethe attended university lectures on anatomy and conducted their own experiments. One experiment involved hooking up a frog leg to various metals. They found no effect until the moisture of Humboldt's breath triggered a reaction that caused the frog leg to leap off the table. Humboldt described this as one of his favorite experiments because it was as if he were "breathing life into" the leg.

During this visit, a thunderstorm killed a farmer and his wife. Humboldt obtained their corpses and analyzed them in the anatomy tower of the university.

In 1794, Humboldt was admitted to the famous group of intellectuals and cultural leaders of

Weimar Classicism

Weimar Classicism () was a German literary and cultural movement, whose practitioners established a new humanism from the synthesis of ideas from Romanticism, Classicism, and the Age of Enlightenment. It was named after the city of Weimar in th ...

. Goethe and

Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

were the key figures at the time. Humboldt contributed (7 June 1795) to Schiller's new periodical, ''Die Horen'', a philosophical

allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

entitled ''(The Life Force, or the Rhodian Genius).''

In this short piece, the only literary story Humboldt ever authored, he tried to summarize the often contradictory results of the thousands of Galvanic experiments he had undertaken.

In 1792 and 1797, Humboldt was in

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

; in 1795 he made a geological and botanical tour through Switzerland and Italy. Although this service to the state was regarded by him as only an apprenticeship to the service of science, he fulfilled its duties with such conspicuous ability that not only did he rise rapidly to the highest post in his department, but he was also entrusted with several important diplomatic missions.

Neither brother attended the funeral of their mother on 19 November 1796. Humboldt had not hidden his aversion to his mother, with one correspondent writing of him after her death, "her death... must be particularly welcomed by you". After severing his official connections, he awaited an opportunity to fulfill his long-cherished dream of travel.

Humboldt was able to spend more time on writing up his research. He had used his own body for experimentation on muscular irritability, recently discovered by

Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani ( , , ; ; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher who studied animal electricity. In 1780, using a frog, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs twitched when ...

and published his results, (Berlin, 1797) (''Experiments on Stimulated Muscle and Nerve Fibres''), enriched in the French translation with notes by Blumenbach.

Spanish American expedition, 1799–1804

Seeking a foreign expedition

With the financial resources to fund his scientific travels, he sought a ship on a major expedition. In the meantime, he went to Paris, where his brother Wilhelm was living. Paris was a great center of scientific learning and his brother and sister-in-law Caroline were well connected in those circles.

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville urged Humboldt to accompany him on a major expedition, likely to last five years, but the French revolutionary

Directoire

The Directory (also called Directorate; ) was the system of government established by the French Constitution of 1795. It takes its name from the committee of 5 men vested with executive power. The Directory governed the French First Republ ...

placed

Nicolas Baudin

Nicolas Thomas Baudin (; 17 February 175416 September 1803) was a French explorer, cartographer, naturalist and hydrographer, most notable for his explorations in Australia and the southern Pacific. He carried a few corms of Gros Michel banana ...

at the head of it rather than the aging scientific traveler. On the postponement of Captain Baudin's proposed voyage of

circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnaviga ...

due to continuing warfare in Europe, which Humboldt had been officially invited to accompany, Humboldt was deeply disappointed. He had already selected scientific instruments for his voyage. He did, however, have a stroke of luck with meeting

Aimé Bonpland

Aimé Jacques Alexandre Bonpland (; 22 August 1773 – 11 May 1858) was a French List of explorers, explorer and botany, botanist who traveled with Alexander von Humboldt in Latin America from 1799 to 1804. He co-authored volumes of the scie ...

, the botanist and physician for the voyage.

Discouraged, the two left Paris for

Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, where they hoped to join

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

in Egypt, but North Africans were in revolt against the French invasion in Egypt and French authorities refused permission to travel. Humboldt and Bonpland eventually found their way to

Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, where their luck changed spectacularly.

Spanish royal authorization, 1799

In Madrid, Humboldt sought authorization to travel to Spain's realms in the Americas; he was aided in obtaining it by the German representative of Saxony at the royal Bourbon court. Baron Forell had an interest in mineralogy and science endeavors and was inclined to help Humboldt. At that time, the

Bourbon Reforms sought to reform administration of the realms and revitalize their economies. At the same time, the

Spanish Enlightenment

The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment () came to History of Spain, Spain in the 18th century with the Spanish royal family, new Bourbon dynasty, following the death of the last House of Habsburg#Spanish Habsburgs: Kings of Spain, Kings of Portugal ...

was in florescence. For Humboldt "the confluent effect of the Bourbon revolution in government and the Spanish Enlightenment had created ideal conditions for his venture".

The Bourbon monarchy had already authorized and funded expeditions, with the

Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru to Chile and Peru (1777–88), New Granada (1783–1816), New Spain (Mexico) (1787–1803), and the

Malaspina Expedition

The Malaspina Expedition (1789–1794) was a five-year maritime scientific exploration commanded by Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra. Although the expedition receives its name from Malaspina, he always insisted on giving Bust ...

(1789–94). These were lengthy, state-sponsored enterprises to gather information about plants and animals from the Spanish realms, assess economic possibilities, and provide plants and seeds for the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid (founded 1755). These expeditions took naturalists and artists, who created visual images as well as careful written observations as well as collecting seeds and plants themselves. Crown officials as early as 1779 issued and systematically distributed ''Instructions concerning the most secure and economic means to transport live plants by land and sea from the most distant countries'', with illustrations, including one for the crates to transport seeds and plants.

When Humboldt requested authorization from the crown to travel to Spanish America, most importantly, with his own financing, it was given positive response. Spain under the Habsburg monarchy had guarded its realms against foreigner travelers and intruders. The Bourbon monarch was open to Humboldt's proposal. Spanish Foreign Minister Don

Mariano Luis de Urquijo

Mariano Luis de Urquijo y Muga (1769 in Bilbao, Spain – 1817 in Paris, France) was Secretary of State (Prime Minister) of Spain in 1799, during the reign of Charles IV. He later held the position again between 1808 and 1813 under Joseph Bo ...

received the formal proposal and Humboldt was presented to the monarch in March 1799. Humboldt was granted access to crown officials and written documentation on Spain's empire. With Humboldt's experience working for the absolutist Prussian monarchy as a government mining official, Humboldt had both the academic training and experience of working well within a bureaucratic structure.

Before leaving Madrid in 1799, Humboldt and Bonpland visited the

Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

, which held results of

Martín Sessé y Lacasta

Martín Sessé y Lacasta (December 11, 1751 – October 4, 1808) was a Spanish botanist, who relocated to New Spain (now Mexico) during the 18th century to study and classify the flora of the territory.

Background

Sessé studied medicine in ...

and

José Mariano Mociño

José Mariano Mociño Suárez Lozano (24 September 1757 – 12 June 1820), or simply José Mariano Mociño, was a naturalist from Mexico.

After having studied philosophy and medicine, he conducted early research on the botany, geology, and anthro ...

's botanical expedition to

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

. Humboldt and Bonpland met

Hipólito Ruiz López

Hipólito Ruiz López (August 8, 1754 in Belorado, Burgos, Spain – 1816 in Madrid), or Hipólito Ruiz, was a Spanish botanist known for researching the floras of Peru and Chile during an expedition under Charles III of Spain, Carlos III from 17 ...

and

José Antonio Pavón y Jiménez of the royal expedition to Peru and Chile in person in Madrid and examined their botanical collections.

Venezuela, 1799–1800

Armed with authorization from the King of Spain, Humboldt and Bonpland made haste to sail, taking the ship ''Pizarro'' from

A Coruña

A Coruña (; ; also informally called just Coruña; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality in Galicia, Spain. It is Galicia's second largest city, behind Vigo. The city is the provincial capital of the province ...

, on 5 June 1799. The ship stopped six days on the island of

Tenerife

Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...

, where Humboldt climbed the volcano

Teide, and then sailed on to the New World, landing at

Cumaná

Cumaná () is the capital city of Venezuela's Sucre State. It is located east of Caracas. Cumaná was one of the first cities founded by Spain in the mainland Americas and is the oldest continuously-inhabited Hispanic-established city in Sout ...

,

Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, on 16 July.

The ship's destination was not originally Cumaná, but an outbreak of typhoid on board meant that the captain changed course from

Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.[Caripe

Caripe is a town in Caripe Municipality in the mountainous north of the state of Monagas in eastern Venezuela.

The official name of the town is Caripe del Guácharo 'Caripe of the Oilbird', referring to a colony of nocturnal birds which lives in ...](_bl ...<br></span></div> to land in northern South America. Humboldt had not mapped out a specific plan of exploration, so that the change did not upend a fixed itinerary. He later wrote that the diversion to Venezuela made possible his explorations along the Orinoco River to the border of Portuguese Brazil. With the diversion, the ''Pizarro'' encountered two large dugout canoes each carrying 18 Guayaqui Indians. The ''Pizarro''s captain accepted the offer of one of them to serve as pilot. Humboldt hired this Indian, named Carlos del Pino, as a guide.

Venezuela from the 16th to the 18th centuries was a relative backwater compared to the seats of the Spanish viceroyalties based in New Spain (Mexico) and Peru, but during the Bourbon reforms, the northern portion of Spanish South America was reorganized administratively, with the 1777 establishment of a captaincy-general based at Caracas. A great deal of information on the new jurisdiction had already been compiled by François de Pons, but was not published until 1806.

Rather than describe the administrative center of Caracas, Humboldt started his researches with the valley of Aragua, where export crops of sugar, coffee, cacao, and cotton were cultivated. Cacao plantations were the most profitable, as world demand for chocolate rose. It is here that Humboldt is said to have developed his idea of human-induced climate change. Investigating evidence of a rapid fall in the water level of the valley's Lake Valencia, Humboldt credited the desiccation to the clearance of tree cover and to the inability of the exposed soils to retain water. With their clear cutting of trees, the agriculturalists were removing the woodland's )

and explored the

Guácharo cavern, where he found the

oilbird

The oilbird (''Steatornis caripensis''), locally known as the , is a bird species found in the northern areas of South America including the Caribbean island of Trinidad. It is the only living species in the genus ''Steatornis'', the family Stea ...

, which he was to make known to science as ''Steatornis caripensis''. He also described the

Guanoco asphalt lake as "The spring of the good priest" ("''Quelle des guten Priesters''"). Returning to Cumaná, Humboldt observed, on the night of 11–12 November, a remarkable

meteor shower

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere at ext ...

(the

Leonids

The Leonids ( ) are a prolific annual meteor shower associated with the comet 55P/Tempel–Tuttle, Tempel–Tuttle, and are also known for their spectacular meteor storms that occur about every 33 years. The Leonids get their name from the loca ...

). He proceeded with Bonpland to

Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

where he climbed the

Avila mount with the young poet

Andrés Bello

Andrés de Jesús María y José Bello López (; November 29, 1781 – October 15, 1865) was a Venezuelan Humanism, humanist, diplomat, poet, legislator, philosopher, educator and philologist, whose political and literary works constitute a ...

, the former tutor of

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24July 178317December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bol ...

, who later became the leader of independence in northern South America. Humboldt met the Venezuelan Bolívar himself in 1804 in Paris and spent time with him in Rome. The documentary record does not support the supposition that Humboldt inspired Bolívar to participate in the struggle for independence, but it does indicate Bolívar's admiration for Humboldt's production of new knowledge on Spanish America.

In February 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland left the coast with the purpose of exploring the course of the

Orinoco River

The Orinoco () is one of the longest rivers in South America at . Its drainage basin, sometimes known as the Orinoquia, covers approximately 1 million km2, with 65% of it in Venezuela and 35% in Colombia. It is the List of rivers by discharge, f ...

and its tributaries. This trip, which lasted four months and covered of wild and largely uninhabited country, had an aim of establishing the existence of the

Casiquiare canal

The Casiquiare river or canal () is a natural distributary of the upper Orinoco flowing southward into the Rio Negro, in Venezuela, South America. As such, it forms a unique natural canal between the Orinoco and Amazon river systems. It is the ...

(a communication between the water systems of the rivers Orinoco and

Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology company

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek myth ...

). Although, unbeknownst to Humboldt, this existence had been established decades before, his expedition had the important results of determining the exact position of the

bifurcation

Bifurcation or bifurcated may refer to:

Science and technology

* Bifurcation theory, the study of sudden changes in dynamical systems

** Bifurcation, of an incompressible flow, modeled by squeeze mapping the fluid flow

* River bifurcation, the for ...

,

and documenting the life of several native tribes such as the Maipures and their extinct rivals the Atures (several words of the latter tribe were transferred to Humboldt by one parrot). Around 19 March 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland discovered dangerous

electric eel

The electric eels are a genus, ''Electrophorus'', of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae, of which they are the only members of the subfamily Electrophorinae. They are known for their electric fish, ability ...

s, whose shock could kill a man. To catch them, locals suggested they drive wild horses into the river, which brought the eels out from the river mud, and resulted in a violent confrontation of eels and horses, some of which died. Humboldt and Bonpland captured and dissected some eels, which retained their ability to shock; both received potentially dangerous electric shocks during their investigations. The encounter made Humboldt think more deeply about electricity and magnetism, typical of his ability to extrapolate from an observation to more general principles. Humboldt returned to the incident in several of his later writings, including his travelogue ''Personal Narrative'' (1814–29), ''Views of Nature'' (1807), and ''Aspects of Nature'' (1849).

Two months later, they explored the territory of the Maipures and that of the then-recently extinct Atures Indians. Humboldt laid to rest the persistent myth of

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

's

Lake Parime

Lake Parime or Lake Parima is a legendary lake located in South America. It was reputedly the location of the fabled city of El Dorado, also known as Manoa, much sought-after by European explorers. Repeated attempts to find the lake failed to con ...

by proposing that the seasonal flooding of the

Rupununi savannah

The Rupununi savannah is a savanna plain in Guyana, in the Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo region. It is part of the Guianan savanna ecoregion of the tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome.

Description

The Rupununi Sav ...

had been misidentified as a lake.

Cuba, 1800, 1804

On 24 November 1800, the two friends set sail for Cuba, landing on 19 December, where they met fellow botanist and

plant collector

A botanical specimen, also called a plant specimen, is a biological specimen of a plant (or part of a plant) used for scientific purposes. Preserved collections of algae, fungi, slime molds, and other organisms traditionally studied by botanists a ...

John Fraser. Fraser and his son had been shipwrecked off the Cuban coast, and did not have a license to be in the Spanish Indies. Humboldt, who was already in Cuba, interceded with crown officials in Havana, as well as giving them money and clothing. Fraser obtained permission to remain in Cuba and explore. Humboldt entrusted Fraser with taking two cases of Humboldt and Bonpland's botanical specimens to England when he returned, for eventual conveyance to the German botanist Willdenow in Berlin. Humboldt and Bonpland stayed in Cuba until 5 March 1801, when they left for the mainland of northern South America again, arriving there on 30 March.

Humboldt is considered to be the "second discoverer of Cuba" due to the scientific and social research he conducted on this Spanish colony. During an initial three-month stay at

Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.[Guanabacoa

Guanabacoa is a colonial township in eastern Havana, Cuba, and one of the 15 municipalities (or boroughs) of the city. It is famous for its historical Santería and is home to the first Afro-Cubans, African Cabildo (Cuba), Cabildo in Havana. Guanab ...](_bl ...<br></span></div>, his first tasks were to survey that city properly and the nearby towns of <div class=)

,

Regla

Regla () is one of the 15 municipalities or boroughs (''municipios'' in Spanish) in the city of Havana, Cuba. It comprises the town of Regla, located at the bottom of Havana Bay in a former aborigine settlement named ''Guaicanamar'', Loma Modelo ...

, and

Bejucal

Bejucal is a municipality and town in the Mayabeque Province of Cuba. It was founded in 1713. It is well known as the terminal station of the first railroad built in Cuba and Latin America in 1837. It also hosts one of the most popular and tradit ...

. He befriended Cuban landowner and thinker

Francisco de Arango y Parreño

Francisco de Arango y Parreño (1765–1837) was a Cuban planter and intellectual. He helped to oversee colonial Cuba's transformation into a major sugar and coffee producer in the last decades of the eighteenth century and the first decades of th ...

; together they visited the area in south Havana, the valleys of

Matanzas

Matanzas (Cuban ; ) is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas Province, Matanzas. Known for its poets, culture, and Afro-American religions, Afro-Cuban folklore, it is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Mat ...

Province, and the

Valley of the Sugar Mills in

Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

. Those three areas were, at the time, the first frontier of sugar production in the island. During those trips, Humboldt collected statistical information on Cuba's population, production, technology and trade, and with Arango, made suggestions for enhancing them. He predicted that the agricultural and commercial potential of Cuba was huge and could be vastly improved with proper leadership in the future.

On their way back to Europe from the Americas, Humboldt and Bonpland stopped again in Cuba, leaving from the port of Veracruz and arriving in Cuba on 7 January 1804, staying until 29 April 1804. In Cuba, he collected plant material and made extensive notes. During this time, he socialized with his scientific and landowner friends, conducted mineralogical surveys, and finished his vast collection of the island's flora and fauna that he eventually published as ''Essai politique sur l'îsle de Cuba''.

The Andes, 1801–1803

After their first stay in Cuba of three months, they returned to the mainland at

Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Region of Colombia, Caribbean Coast Region, along the Caribbean Sea. Cartagena's past ...

(now in Colombia), a major center of trade in northern South America. Ascending the swollen stream of the

Magdalena River

The Magdalena River (, ; less commonly ) is the main river of Colombia, flowing northward about through the western half of the country. It takes its name from the biblical figure Mary Magdalene. It is navigable through much of its lower reaches, ...

to Honda, they arrived in Bogotá on 6 July 1801, where they met the Spanish botanist

José Celestino Mutis

José Celestino Bruno Mutis y Bosio (6 April 1732 – 11 September 1808) was a Spanish people, Spanish priest, botanist and mathematician. He was a significant figure in the Spanish American Enlightenment, whom Alexander von Humboldt met with ...

, head of the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada, staying there until 8 September 1801. Mutis was generous with his time and gave Humboldt access to the huge pictorial record he had compiled since 1783. Mutis was based in Bogotá, but as with other Spanish expeditions, he had access to local knowledge and a workshop of artists, who created highly accurate and detailed images. This type of careful recording meant that even if specimens were not available to study at a distance, "because the images travelled, the botanists did not have to". Humboldt was astounded at Mutis's accomplishment; when Humboldt published his first volume on botany, he dedicated it to Mutis "as a simple mark of our admiration and acknowledgement".

Humboldt had hopes of connecting with the French sailing expedition of Baudin, now finally underway, so Bonpland and Humboldt hurried to Ecuador. They crossed the frozen ridges of the

Cordillera Real and reached

Quito

Quito (; ), officially San Francisco de Quito, is the capital city, capital and second-largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its metropolitan area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha Province, P ...

on 6 January 1802, after a tedious and difficult journey.

Their stay in Ecuador was marked by the ascent of

Pichincha and their climb of

Chimborazo

Chimborazo () is a stratovolcano situated in Ecuador in the Cordillera Occidental (Ecuador), Cordillera Occidental range of the Andes. Its last known Types of volcanic eruptions, eruption is believed to have occurred around AD 550. Although not ...

, where Humboldt and his party reached an altitude of . This was a world record at the time (for a westerner—

Incas

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilisation rose fr ...

had reached much higher altitudes centuries before), but 1000 feet short of the summit. Humboldt's journey concluded with an expedition to the sources of the Amazon ''en route'' for

Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

, Peru.

At

Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists ...

, the main port for Peru, Humboldt observed the

transit of Mercury

file:Mercury transit symbol.svg, frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Mercury across the Sun takes place when the planet Mercury (planet), Mercury passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet. During a Astronomical transit, transit, Merc ...

on 9 November and studied the fertilizing properties of

guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

, rich in nitrogen, the subsequent introduction of which into Europe was due mainly to his writings.

New Spain (Mexico), 1803–1804

Humboldt and Bonpland had not intended to go to New Spain, but when they were unable to join a voyage to the Pacific, they left the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil and headed for

Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , ; ), is a city and Port of Acapulco, major seaport in the Political divisions of Mexico, state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Located on a deep, semicirc ...

on Mexico's west coast. Even before Humboldt and Bonpland started on their way to New Spain's

capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

on Mexico's central plateau, Humboldt realized the captain of the vessel that brought them to Acapulco had reckoned its location incorrectly. Since Acapulco was the main west-coast port and the terminus of the

Asian trade from the Spanish Philippines, having accurate maps of its location was extremely important. Humboldt set up his instruments, surveying the deep-water bay of Acapulco, to determine its longitude.

Humboldt and Bonpland landed in Acapulco on 15 February 1803, and from there they went to

Taxco

Taxco de Alarcón (; usually referred to as simply Taxco) is a small city and administrative center of Taxco de Alarcón Municipality located in the Mexico, Mexican state of Guerrero. Taxco is located in the north-central part of the state, from ...

, a silver-mining town in modern

Guerrero

Guerrero, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guerrero, is one of the 32 states that compose the administrative divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Guerrero, 85 municipalities. The stat ...

. In April 1803, he visited

Cuernavaca

Cuernavaca (; , "near the woods" , Otomi language, Otomi: ) is the capital and largest city of the Mexican state, state of Morelos in Mexico. Along with Chalcatzingo, it is likely one of the origins of the Mesoamerica, Mesoamerican civilizatio ...

,

Morelos

Morelos, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Morelos, is a landlocked state located in south-central Mexico. It is one of the 32 states which comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Mun ...

. Impressed by its climate, he nicknamed the city the ''City of Eternal Spring''. Humboldt and Bonpland arrived in Mexico City, having been officially welcomed via a letter from the king's representative in New Spain, Viceroy Don

José de Iturrigaray

José Joaquín Vicente de Iturrigaray y Aróstegui, KOS (27 June 1742, Cádiz, Spain – 22 August 1815, Madrid) was a Spanish military officer and viceroy of New Spain, from 4 January 1803 to 16 September 1808, during Napoleon's invasion ...

. Humboldt was also given a special passport to travel throughout New Spain and letters of introduction to intendants, the highest officials in New Spain's administrative districts (intendancies). This official aid to Humboldt allowed him to have access to crown records, mines, landed estates, canals, and Mexican antiquities from the prehispanic era. Humboldt read the writings of Bishop-elect of the important diocese of Michoacan

Manuel Abad y Queipo

Manuel Abad y Queipo (26 August 1751 – 15 September 1825) was a Spanish Roman Catholic Bishop of Michoacán in the Viceroyalty of New Spain at the time of the Mexican War of Independence. He was "an acute social commentator of late colonial ...

, a

classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, eco ...

, that were directed to the crown for the improvement of New Spain.

They spent the year in the viceroyalty, traveling to different Mexican cities in the central plateau and the northern mining region. The first journey was from Acapulco to Mexico City, through what is now the Mexican state of

Guerrero

Guerrero, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guerrero, is one of the 32 states that compose the administrative divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Guerrero, 85 municipalities. The stat ...

. The route was suitable only for mule train, and all along the way, Humboldt took measurements of elevation. When he left Mexico a year later in 1804, from the east coast port of Veracruz, he took a similar set of measures, which resulted in a chart in the ''Political Essay'', the physical plan of Mexico with the dangers of the road from Acapulco to Mexico City, and from Mexico City to Veracruz. This visual depiction of elevation was part of Humboldt's general insistence that the data he collected be presented in a way more easily understood than statistical charts. A great deal of his success in gaining a more general readership for his works was his understanding that "anything that has to do with extent or quantity can be represented geometrically. Statistical projections

harts and graphs which speak to the senses without tiring the intellect have the advantage of bringing attention to a large number of important facts".

Humboldt was impressed with Mexico City, which at the time was the largest city in the Americas, and one that could be counted as modern. He declared "no city of the new continent, without even excepting those of the United States, can display such great and solid scientific establishments as the capital of Mexico". He pointed to the

Royal College of Mines

The Royal School of Mines comprises the departments of Earth Science and Engineering, and Materials at Imperial College London. The Centre for Advanced Structural Ceramics and parts of the London Centre for Nanotechnology and Department of Bioe ...

, the

Royal Botanical Garden and the

Royal Academy of San Carlos as exemplars of a metropolitan capital in touch with the latest developments on the continent and insisting on its modernity. He also recognized important

criollo

Criollo or criolla (Spanish for creole) may refer to:

People

* Criollo people, a social class in the Spanish colonial system.

Animals

* Criollo duck, a species of duck native to Central and South America.

* Criollo cattle, a group of cattle bre ...

savants in Mexico, including

José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez

José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez (20 November 1737 – 2 February 1799) was a priest in New Spain, scientist, historian, and cartographer.

Life and career

He was born in Ozumba in 1737, the child of Felipe de Alzate and María Josefa Ramír ...

, who died in 1799, just before Humboldt's visit; Miguel Velásquez de León; and

Antonio de León y Gama

Antonio de León y Gama (1735–1802) was a Mexican astronomer, anthropologist and writer. When in 1790 the Aztec calendar stone (also called sun stone) was discovered buried under the main square of Mexico City, he published an essay about i ...

.

Humboldt spent time at the Valenciana silver mine in

Guanajuato

Guanajuato, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato, is one of the 32 states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Guanajuato, 46 municipalities and its cap ...

, central New Spain, at the time the most important in the Spanish empire. The bicentennial of his visit in Guanajuato was celebrated with a conference at the

University of Guanajuato

The Universidad de Guanajuato (in English, the University of Guanajuato) is a university based in the Mexican state of Guanajuato, made up of about 47,108 students in programs ranging from high school level to the doctorate level. Over 30,89 ...

, with Mexican academics highlighting various aspects of his impact on the city. Humboldt could have simply examined the geology of the fabulously rich mine, but he took the opportunity to study the entire mining complex as well as analyze mining statistics of its output. His report on silver mining is a major contribution, and considered the strongest and best informed section of his ''Political Essay''. Although Humboldt was himself a trained geologist and mining inspector, he drew on mining experts in Mexico. One was

Fausto Elhuyar

Fausto de Elhuyar (11 October 1755 – 6 February 1833) was a Spanish chemist, and the first to isolate tungsten with his brother Juan José Elhuyar in 1783. He was in charge, under a King of Spain commission, of organizing the School of Mines ...

, then head of the General Mining Court in Mexico City, who, like Humboldt was trained in Freiberg. Another was

Andrés Manuel del Río

Andrés Manuel del Río y Fernández (10 November 1764 – 23 March 1849) was a Spanish scientist, natural history, naturalist and engineer who discovered compounds of ''vanadium'' in 1801. He proposed that the element be given the name ''panchr ...

, director of Royal College of Mines, whom Humboldt knew when they were both students in Freiberg. The Bourbon monarchs had established the mining court and the college to elevate mining as a profession, since revenues from silver constituted the crown's largest source of income. Humboldt also consulted other German mining experts, who were already in Mexico. While Humboldt was a welcome foreign scientist and mining expert, the Spanish crown had established fertile ground for Humboldt's investigations into mining.

Spanish America's ancient civilizations were a source of interest for Humboldt, who included images of Mexican manuscripts (or codices) and Inca ruins in his richly illustrated ''Vues des cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l'Amerique'' (1810–1813), the most experimental of Humboldt's publications, since it does not have "a single ordering principle" but his opinions and contentions based on observation. For Humboldt, a key question was the influence of climate on the development of these civilizations. When he published his ''Vues des cordillères'', he included a color image of the

Aztec calendar stone

The Aztec sun stone () is a late post-classic Mexica sculpture housed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, and is perhaps the most famous work of Mexica sculpture. It measures in diameter and thick, and weighs . Shortly after ...

, which had been discovered buried in the

main plaza of Mexico City in 1790, along with select drawings of the

Dresden Codex

The ''Dresden Codex'' is a Maya book, which was believed to be the oldest surviving book written in the Americas, dating to the 11th or 12th century. However, in September 2018 it was proven that the Maya Codex of Mexico, previously known as th ...

and others he sought out later in European collections. His aim was to muster evidence that these pictorial and sculptural images could allow the reconstruction of prehispanic history. He sought out Mexican experts in the interpretation of sources from there, especially Antonio Pichardo, who was the literary executor of

Antonio de León y Gama

Antonio de León y Gama (1735–1802) was a Mexican astronomer, anthropologist and writer. When in 1790 the Aztec calendar stone (also called sun stone) was discovered buried under the main square of Mexico City, he published an essay about i ...

's work. For American-born Spaniards (

criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of full Spanish descent born in the viceroyalties. In different Latin American countries, the word has come to have different meanings, mostly referring to the local ...

) who were seeking sources of pride in Mexico's ancient past, Humboldt's recognition of these ancient works and dissemination in his publications was a boon. He read the work of exiled Jesuit

Francisco Javier Clavijero

Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray, SJ (sometimes Italianized as Francesco Saverio Clavigero; September 9, 1731 – April 2, 1787) was a Mexican Jesuit teacher, scholar and historian. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish provinces ...

, which celebrated Mexico's prehispanic civilization, and which Humboldt invoked to counter the pejorative assertions about the new world by Buffon, de Pauw, and Raynal. Humboldt ultimately viewed both the prehispanic realms of Mexico and Peru as despotic and barbaric. However, he also drew attention to indigenous monuments and artifacts as cultural productions that had "both ... historical ''and'' artistic significance".

One of his most widely read publications resulting from his travels and investigations in Spanish America was the ''Essai politique sur le royaum de la Nouvelle Espagne'', quickly translated to English as ''Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain'' (1811). This treatise was the result of Humboldt's own investigations as well as the generosity of Spanish colonial officials for statistical data.

The United States, 1804

Leaving from Cuba, Humboldt decided to take an unplanned short visit to the United States. Knowing that the current U.S. president,

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, was himself a scientist, Humboldt wrote to him saying that he would be in the United States. Jefferson warmly replied, inviting him to visit the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

in the nation's new capital. In his letter Humboldt had gained Jefferson's interest by mentioning that he had discovered

mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

teeth near the Equator. Jefferson had previously written that he believed mammoths had never lived so far south. Humboldt had also hinted at his knowledge of New Spain.

Arriving in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, which was a center of learning in the U.S., Humboldt met with some of the major scientific figures of the era, including chemist and anatomist

Caspar Wistar, who pushed for compulsory smallpox vaccination, and botanist

Benjamin Smith Barton

Benjamin Smith Barton (February10, 1766December19, 1815) was an American botanist, naturalist, and physician. He was one of the first professors of natural history in the United States and built the largest collection of botanical specimens in the ...

, as well as physician

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was an American revolutionary, a Founding Father of the United States and signatory to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social refor ...

, a signer of the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, who wished to hear about

cinchona

''Cinchona'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the Tropical Andes, tropical Andean forests of western South America. A few species are ...

bark from a South American tree, which cured fevers. Humboldt's treatise on cinchona was published in English in 1821.

After arriving in Washington D.C, Humboldt held numerous intense discussions with Jefferson on both scientific matters and also his year-long stay in New Spain. Jefferson had only recently concluded the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, which now placed New Spain on the southwest border of the United States. The Spanish minister in Washington, D.C. had declined to furnish the U.S. government with information about Spanish territories, and access to the territories was strictly controlled. Humboldt was able to supply Jefferson with the latest information on the population, trade agriculture and military of New Spain. This information would later be the basis for his ''Essay on the Political Kingdom of New Spain'' (1810).

Jefferson was unsure of where the border of the newly-purchased

Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

was precisely, and Humboldt wrote him a two-page report on the matter. Jefferson would later refer to Humboldt as "the most scientific man of the age".

Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan-American politician, diplomat, ethnologist, and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

, Secretary of the Treasury, said of Humboldt "I was delighted and swallowed more information of various kinds in less than two hours than I had for two years past in all I had read or heard." Gallatin, in turn, supplied Humboldt with information he sought on the United States.

After six weeks, Humboldt set sail for Europe from the mouth of the

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

and landed at

Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

on 3 August 1804.

Travel diaries

Humboldt kept a detailed diary of his sojourn to Spanish America, running some 4,000 pages, which he drew on directly for his multiple publications following the expedition. The leather-bound diaries themselves are now in Germany, having been returned from Russia to East Germany, where they were taken by the Red Army after World War II. Following German reunification, the diaries were returned to a descendant of Humboldt. For a time, there was concern about their being sold, but that was averted. A government-funded project to digitize the Spanish American expedition as well as his later Russian expedition has been undertaken (2014–2017) by the University of Potsdam and the German State Library–Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

Achievements of the Hispanic American expedition

Humboldt's decades' long endeavor to publish the results of this expedition not only resulted in multiple volumes, but also made his international reputation in scientific circles. Humboldt came to be well-known with the reading public as well, with popular, densely illustrated, condensed versions of his work in multiple languages. Bonpland, his fellow scientist and collaborator on the expedition, collected botanical specimens and preserved them, but unlike Humboldt who had a passion to publish, Bonpland had to be prodded to do the formal descriptions. Many scientific travelers and explorers produced huge visual records, which remained unseen by the general public until the late nineteenth century, in the case of the Malaspina Expedition, and even the late twentieth century, when Mutis's botanical, some 12,000 drawings from New Granada, was published. Humboldt, by contrast, published immediately and continuously, using and ultimately exhausting his personal fortune, to produce both scientific and popular texts. Humboldt's name and fame were made by his travels to Spanish America, particularly his publication of the ''Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain''. His image as the premier European scientist was a later development.

For the Bourbon crown, which had authorized the expedition, the returns were not only tremendous in terms of sheer volume of data on their New World realms, but in dispelling the vague and pejorative assessments of the New World by

Guillaume-Thomas Raynal,

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, and cosmology, cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now ca ...

, and

William Robertson. The achievements of the Bourbon regime, especially in New Spain, were evident in the precise data Humboldt systematized and published.

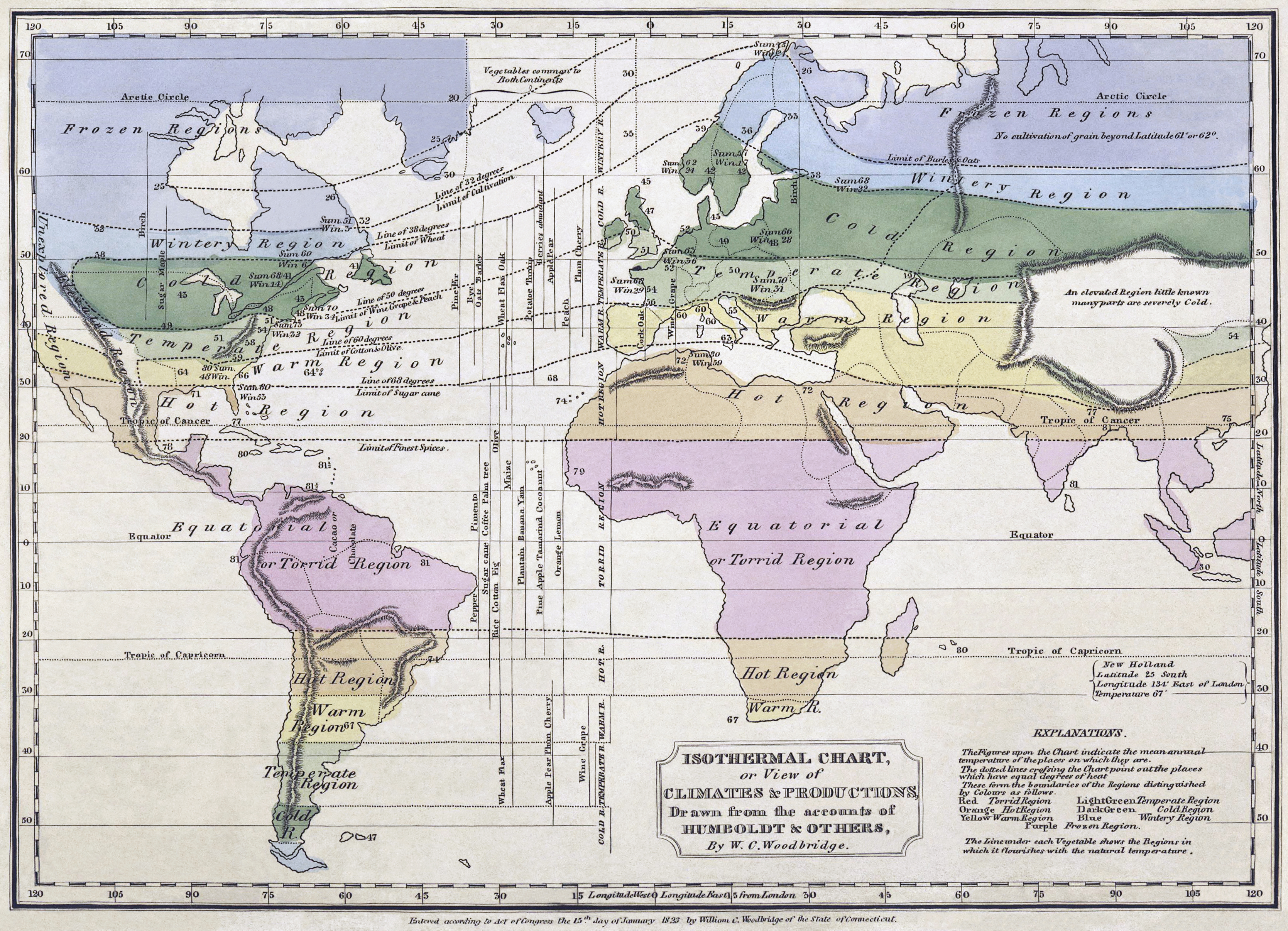

This memorable expedition may be regarded as having laid the foundation of the sciences of

physical geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, h ...

,

plant geography

Phytogeography (from Greek φυτόν, ''phytón'' = "plant" and γεωγραφία, ''geographía'' = "geography" meaning also distribution) or botanical geography is the branch of biogeography that is concerned with the geographic distribution o ...

, and

meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

. Key to that was Humboldt's meticulous and systematic measurement of phenomena with the most advanced instruments then available. He closely observed plant and animal species in situ, not just in isolation, noting all elements in relation to one other. He collected specimens of plants and animals, dividing the growing collection so that if a portion was lost, other parts might survive.

Humboldt saw the need for an approach to science that could account for the harmony of nature among the diversity of the physical world. For Humboldt, "the unity of nature" meant that it was the interrelation of all

physical sciences

Physical science is a branch of natural science that studies non-living systems, in contrast to life science. It in turn has many branches, each referred to as a "physical science", together is called the "physical sciences".

Definition

...

—such as the conjoining between

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

,

meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

and

geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

—that determined where specific plants grew. He found these relationships by unraveling myriad, painstakingly collected data, data extensive enough that it became an enduring foundation upon which others could base their work. Humboldt viewed nature

holistically

Holism is the interdisciplinary idea that systems possess properties as wholes apart from the properties of their component parts.Julian Tudor Hart (2010''The Political Economy of Health Care''pp.106, 258

The aphorism "The whole is greater than th ...

, and tried to explain natural phenomena without the appeal to religious dogma. He believed in the central importance of observation, and as a consequence had amassed a vast array of the most sophisticated scientific instruments then available. Each had its own velvet lined box and was the most accurate and portable of its time; nothing quantifiable escaped measurement. According to Humboldt, everything should be measured with the finest and most modern instruments and sophisticated techniques available, for that collected data was the basis of all scientific understanding.

This quantitative methodology would become known as

Humboldtian science

Humboldtian science refers to a movement in science in the 19th century closely connected to the work and writings of German scientist, naturalist, and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. It maintained a certain ethics of precision and observation, ...

. Humboldt wrote "Nature herself is sublimely eloquent. The stars as they sparkle in firmament fill us with delight and ecstasy, and yet they all move in orbit marked out with mathematical precision." However,

Andreas Daum

Andreas W. Daum is a German-American historian who specializes in modern German and transatlantic history, as well as the history of knowledge and global exploration.

Daum received his Ph.D. summa cum laude in 1995 from the Ludwig Maximilian Unive ...

has recently revisited the concept of Humboldtian Science and set it apart from "Humboldt's science".

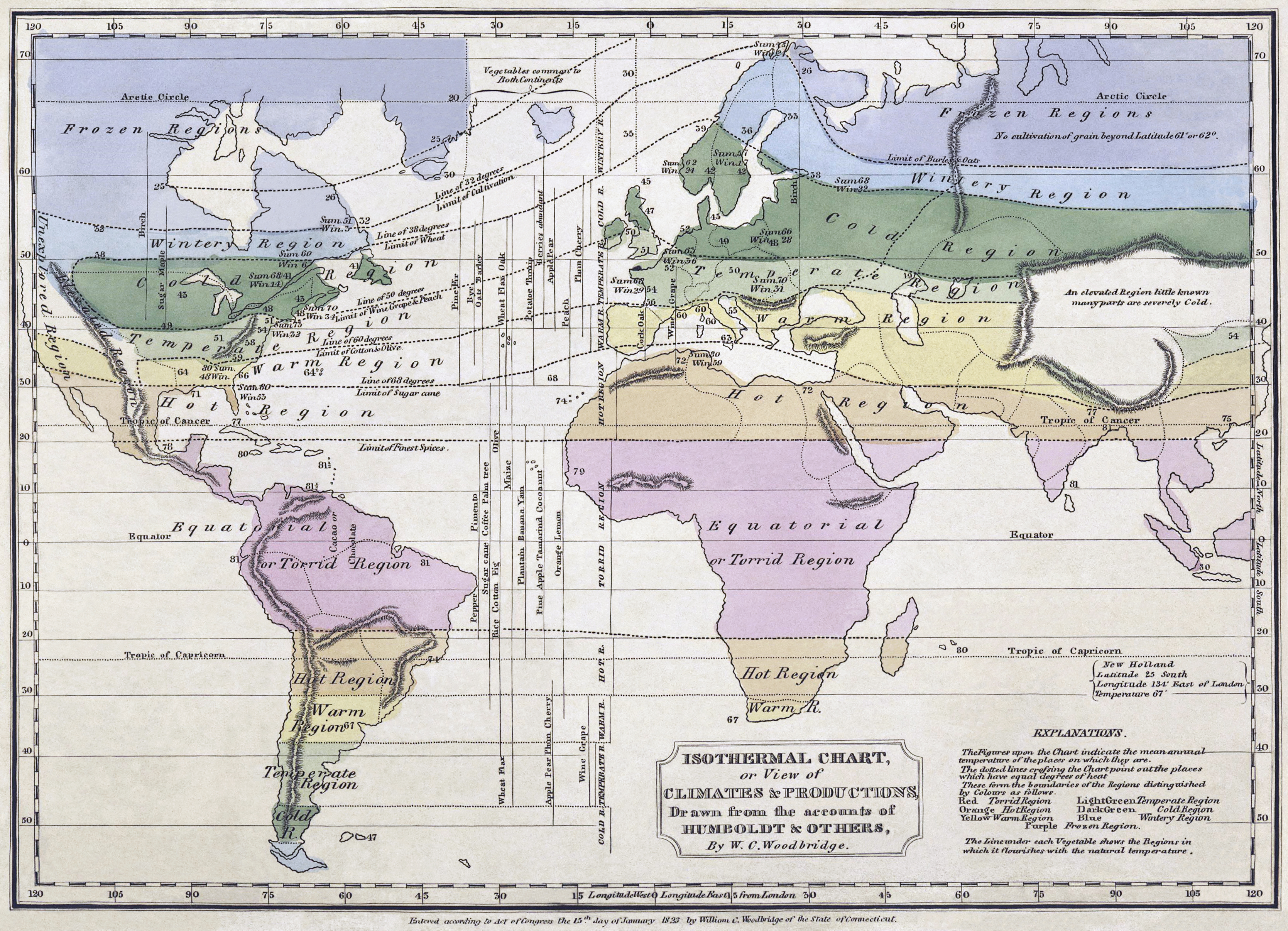

His ''Essay on the Geography of Plants'' (published first in French and then German, both in 1807) was based on the then novel idea of studying the distribution of organic life as affected by varying physical conditions.

This was most famously depicted in his published cross-section of Chimborazo, approximately two feet by three feet (54 cm x 84 cm) color pictorial, he called ''Ein Naturgemälde der Anden'' and what is also called the Chimborazo Map. It was a fold-out at the back of the publication. Humboldt first sketched the map when he was in South America, which included written descriptions on either side of the cross-section of Chimborazo. These detailed the information on temperature, altitude, humidity, atmosphere pressure, and the animal and plants (with their scientific names) found at each elevation. Plants from the same genus appear at different elevations. The depiction is on an east-west axis going from the Pacific coast lowlands to the Andean range of which Chimborazo was a part, and the eastern Amazonian basin. Humboldt showed the three zones of coast, mountains, and Amazonia, based on his own observations, but he also drew on existing Spanish sources, particularly

Pedro Cieza de León

Pedro Cieza de León ( Llerena, Spain c. 1518 or 1520 – Seville, Spain July 2, 1554) was a Spanish conquistador and chronicler of Peru and Popayán. He is known primarily for his extensive work, ''Crónicas del Perú'' (The Chronicle of Peru), ...

, which he explicitly referred to. The Spanish American scientist

Francisco José de Caldas

Francisco José de Caldas (October 4, 1768 – October 28, 1816) was a Neogranadine lawyer, military engineer, self-taught naturalist, mathematician, geographer and inventor (he created the first hypsometer), who was executed by orders of Gene ...