Aldo Moro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aldo Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and prominent member of

Moro's first government was unevenly supported by the DC but also by the PCI, along with the PSDI and the Italian Republican Party (PRI). The coalition, which replaced the previous

Moro's first government was unevenly supported by the DC but also by the PCI, along with the PSDI and the Italian Republican Party (PRI). The coalition, which replaced the previous

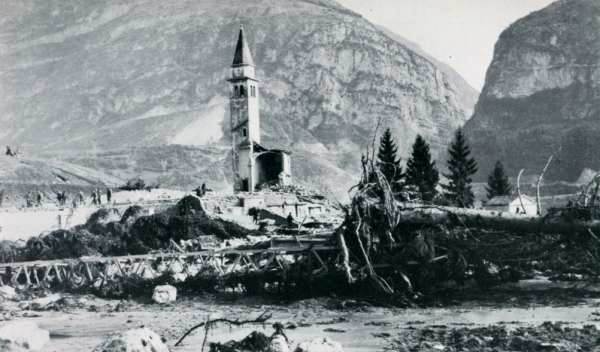

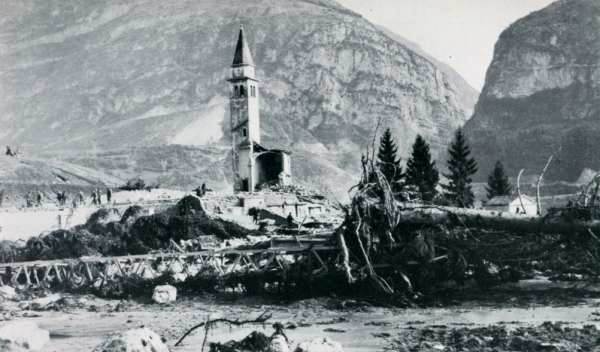

During his premiership, Moro had to face the outcome of one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, the Vajont Dam disaster. On 9 October 1963, a few weeks before his oath as prime minister, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of

During his premiership, Moro had to face the outcome of one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, the Vajont Dam disaster. On 9 October 1963, a few weeks before his oath as prime minister, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of

On 25 June 1964, the government was beaten on the budget law for the Italian Ministry of Education concerning the financing of private education. On the same day, Moro resigned. During the presidential consultations for the formation of a new cabinet, Segni, the then moderate DC member and

On 25 June 1964, the government was beaten on the budget law for the Italian Ministry of Education concerning the financing of private education. On the same day, Moro resigned. During the presidential consultations for the formation of a new cabinet, Segni, the then moderate DC member and

During his premiership, Moro signed the Osimo Treaty with the

During his premiership, Moro signed the Osimo Treaty with the

After the 1976 Italian general election, the PCI gained a historic 34% votes and Moro became a vocal supporter of the necessity of starting a dialogue between DC and PCI. Moro's main aim was to widen the democratic base of the government, including the PCI in the parliamentary majority, in which the cabinets should have been able to represent a larger number of voters and parties. According to him, the DC should have been at the centre of a coalition system based on the principles of consociative democracy. This process was known as Historic Compromise.

Between 1976 and 1977, Berlinguer's PCI broke with the

After the 1976 Italian general election, the PCI gained a historic 34% votes and Moro became a vocal supporter of the necessity of starting a dialogue between DC and PCI. Moro's main aim was to widen the democratic base of the government, including the PCI in the parliamentary majority, in which the cabinets should have been able to represent a larger number of voters and parties. According to him, the DC should have been at the centre of a coalition system based on the principles of consociative democracy. This process was known as Historic Compromise.

Between 1976 and 1977, Berlinguer's PCI broke with the

On 16 March 1978, on via Fani, in Rome, a unit of the militant far-left organization known as

On 16 March 1978, on via Fani, in Rome, a unit of the militant far-left organization known as

Interview of Steve Pieczenik put on-line

by Rue 89Hubert Artus

Pourquoi le pouvoir italien a lâché Aldo Moro, exécuté en 1978

(Why the Italian Power let go of Aldo Moro, executed in 1978), '' Rue 89'', 6 February 2008 Pieczenik maintained that the United States had to "instrumentalize the Red Brigades". According to him, the decision to have Moro killed was taken during the fourth week of his detention, when Moro was thought to be revealing state secrets in his letters, namely the existence of Gladio. In another interview, Cossiga revealed that the Crisis Committee had also leaked, in a form of black propaganda, a false statement attributed to the Red Brigades that Moro was already dead. This was intended to communicate to the kidnappers that further negotiations would be useless since the government had written Moro off.

As a Christian democrat with social-democratic tendencies, Moro is widely considered one of the ideological fathers of modern Italian centre-left, having led the first centre-left government in the history of the Italian Republic, the Organic centre-left. He was the leading figure of the left wing of the DC, which he steered towards the left as the party's secretary-general from 1959 to 1964. While he was prime minister, a

As a Christian democrat with social-democratic tendencies, Moro is widely considered one of the ideological fathers of modern Italian centre-left, having led the first centre-left government in the history of the Italian Republic, the Organic centre-left. He was the leading figure of the left wing of the DC, which he steered towards the left as the party's secretary-general from 1959 to 1964. While he was prime minister, a

Ma la verità vera ancora non c'è

– interview with Giovanni Moro (Aldo Moro's son) at ''

Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

(DC) and its centre-left

Centre-left politics is the range of left-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. Ideologies commonly associated with it include social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, and green politics. Ideas commo ...

wing. He served as prime minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

in five terms from December 1963 to June 1968 and from November 1974 to July 1976.

Moro served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs

The minister of foreign affairs is the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Italy), Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Italy. The office was one of the positions which Italy inherited from the Kingdom of Sardinia where it was the most ancient mi ...

from May 1969 to July 1972 and again from July 1973 to November 1974. During his ministry, he implemented a pro-Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

policy. Moreover, he was appointed Italy's Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

and of Public Education

A state school, public school, or government school is a primary school, primary or secondary school that educates all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in part by taxation and operated by the government of the state. State-f ...

during the 1950s. From March 1959 until January 1964, he served as secretary of the DC. On 16 March 1978, he was kidnapped by the far-left terrorist group Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

; he was killed after 55 days of captivity.

Moro was one of Italy's longest-serving post-war prime ministers, leading the country for more than six years. Moro implemented a series of social and economic reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

s that modernized the country. Due to his accommodation with the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

leader Enrico Berlinguer

Enrico Berlinguer (; 25 May 1922 – 11 June 1984) was an Italian politician and statesman. Considered the most popular leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), he led the PCI as the national secretary from 1972 until his death during a te ...

, known as the Historic Compromise, Moro is widely considered to be one of the most prominent fathers of the modern Italian centre-left.

Early life

Aldo Romeo Luigi Moro was born on 23 September 1916 in Maglie, nearLecce

Lecce (; ) is a city in southern Italy and capital of the province of Lecce. It is on the Salentine Peninsula, at the heel of the Italian Peninsula, and is over two thousand years old.

Because of its rich Baroque architecture, Lecce is n ...

, into a family from Ugento in the Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

region of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. His father, Renato Moro, was a school inspector, while his mother, Fida Sticchi, was a teacher. At the age of 4, he moved with his family to Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

; they soon moved back to Apulia, where he gained a classical high school degree at Archita lyceum in Taranto

Taranto (; ; previously called Tarent in English) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Taranto, serving as an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base.

Founded by Spartans ...

. In 1934, his family moved to Bari

Bari ( ; ; ; ) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia Regions of Italy, region, on the Adriatic Sea in southern Italy. It is the first most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy. It is a port and ...

. There, he studied law at the University of Bari and graduated in 1939. After graduation, he became a professor of philosophy of law and colonial policy (1941) and of criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It proscribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and Well-being, welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal l ...

(1942) at the University of Bari.

In 1935, Moro joined the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI) of Bari. In 1939, under the approval of Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, whom he had befriended, Moro was chosen as president of the association. He kept the post until 1942 when he was forced to fight in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and was succeeded by Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti ( ; ; 14 January 1919 – 6 May 2013) was an Italian politician and wikt:statesman, statesman who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy in seven governments (1972–1973, 1976–1979, and 1989–1992), and was leader of th ...

, who at the time was a law student from Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. During his university years, Italy was ruled by the fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

regime of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, and Moro took part in students competitions known as Lictors of Culture and Art organized by the local fascist students' organization, the University Fascist Groups. In 1943, along with other Catholic students, he founded the periodical ''La Rassegna'', which was published until 1945.

In July 1943, Moro contributed, along with Andreotti, Mario Ferrari Aggradi, Paolo Emilio Taviani, Guido Gonella, , Ferruccio Pergolesi, Vittore Branca, Giorgio La Pira, and Giuseppe Medici, to the creation of the Code of Camaldoli, a document planning of economic policy drawn up by members of the Italian Catholic forces. It served as inspiration and guideline for economic policy of the future Christian democrats. In 1945, he married Eleonora Chiavarelli (1915–2010), with whom he had four children: Maria Fida (born 1946), Anna (born 1949), Agnese (born 1952), and Giovanni (born 1958). In 1963, Moro was transferred to La Sapienza University

The Sapienza University of Rome (), formally the Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", abbreviated simply as Sapienza ('Wisdom'), is a Public university, public research university located in Rome, Italy. It was founded in 1303 and is ...

of Rome as a professor of the institutions of law and criminal procedure.

Early political career

Moro developed his interest in politics between 1943 and 1945. Initially, he seemed to be very interested in the social-democratic component of theItalian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI) but then started cooperating with other Christian-democratic politicians in opposition to the Italian fascist regime. During these years, he met Alcide De Gasperi, Mario Scelba, Giovanni Gronchi, and Amintore Fanfani. On 19 March 1943, the group reunited in the house of Giuseppe Spataro and officially formed the Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

(DC) party. In the DC, he joined the left-wing faction led by Giuseppe Dossetti

Giuseppe Dossetti (13 February 1913 – 15 December 1996) was an Italian professor, politician, and Catholic priest who served as a member of the Chamber of Deputies from 1948 to 1952. A prominent anti-fascist, Dossetti previously served as ...

, of whom he became a close ally. In 1945, he became director of the magazine ''Studium'' and president of the Graduated Movement of Catholic Action ('' Azione Cattolica'', AC), a widespread Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

lay association.

After being appointed vice-president of the DC, Moro was elected in the 1946 Italian general election a member of the Constituent Assembly of Italy, where he took part in the work to redact the Italian Constitution. It was during this period that his relations with the Italian Socialist Democratic Party (PSDI) and Italian social-democrats began. In 1946, Moro ran for the Bari–Foggia constituency, where he received nearly 28,000 votes. In the 1948 Italian general election, he was elected with 63,000 votes to the newly formed Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

, and was appointed Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs in the fifth De Gasperi government from 23 May 1948 to 27 January 1950. After Dossetti's retirement in 1952, Moro founded, along with Antonio Segni, Emilio Colombo, and Mariano Rumor, the Democratic Initiative faction, which was led by his old friend Fanfani.

In government

In the 1953 Italian general election, Moro was re-elected to the Chamber of Deputies, where he held the position of chairman of the DC parliamentary group. In 1955, was appointed as Italian Minister of Grace and Justice in the first Segni government led by Segni asPrime Minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

. In 1956, he was among the most popular candidates, receiving the most votes during the party's congress. In May 1957, the PSDI withdrew its support to the government and Segni resigned on 6 May 1957.

On 20 May 1957, Adone Zoli was sworn in as the new head of government and Moro was appointed Italian Minister of Education. After the 1958 Italian general election, Zoli resigned. On 1 July 1958, Fanfani was sworn in as the new prime minister at the head of a coalition government with the PSDI and case-by-case support by the Italian Republican Party (PRI). Moro was confirmed as the head of Italian education and remained in office until February 1959. During his tenure, he introduced the study of civic education in schools.

In March 1959, after Fanfani's resignation as prime minister, a new congress was called. The leaders of the Democratic Initiative faction reunited themselves in the Convent of Dorothea of Caesarea, where they abandoned the leftist policies promoted by Fanfani and founded the ''Dorotei'' (Dorotheans) faction. In the party's national council, Moro was elected secretary of the DC and was then confirmed in the October's congress held in Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

. After the brief right-wing government led by Fernando Tambroni in 1960, supported by the decisive votes of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI), the renovated alliance between Moro as secretary and Fanfani as prime minister led the subsequent National Congress, held in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

in 1962, to approve with a large majority a line of collaboration with the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI).

The 1963 Italian general election was characterized by a lack of consensus for the DC; in fact, the election was held after the launch of the centre-left

Centre-left politics is the range of left-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. Ideologies commonly associated with it include social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, and green politics. Ideas commo ...

formula by the DC, a coalition based upon the alliance with the PSI, which had left their alignment with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Some rightist electors abandoned the DC for the Italian Liberal Party (PLI), which was asking for a centre-right

Centre-right politics is the set of right-wing politics, right-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. It is commonly associated with conservatism, Christian democracy, liberal conservatism, and conservative liberalis ...

government and received votes also from the quarrelsome monarchist area. Moro refused the office of prime minister, preferring to provisionally maintain his more influential post at the head of the party. Initially, the DC decided to replace Fanfani with a provisional administration led by an impartial president of the Chamber of Deputies, Giovanni Leone. When the congress of the PSI in autumn authorized a full engagement of the party into the government, Leone resigned and Moro became the new prime minister.

First term as prime minister

Moro's first government was unevenly supported by the DC but also by the PCI, along with the PSDI and the Italian Republican Party (PRI). The coalition, which replaced the previous

Moro's first government was unevenly supported by the DC but also by the PCI, along with the PSDI and the Italian Republican Party (PRI). The coalition, which replaced the previous Centrism

Centrism is the range of political ideologies that exist between left-wing politics and right-wing politics on the left–right political spectrum. It is associated with moderate politics, including people who strongly support moderate policie ...

system, was known as the Organic centre-left and was characterized by consociationalist and social corporatist tendencies.

Social reforms

During Moro's premiership, a wide range of social reforms was carried out. This included the 1967 Bridge Law (''Legge Ponte''). A bill approved on 21 July 1965 extended the program ofsocial security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

.

Despite mistrust and opposition, particularly when the Italian economic miracle came to an end and the government had to control the rise of inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

, the reforms continued. There was an increase in minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

. Two 1966 laws provided traders with insurance.''Growth to Limits: The Western European Welfare States Since World War II''. Vol. 4, edited by Peter Flora.

Vajont Dam disaster

During his premiership, Moro had to face the outcome of one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, the Vajont Dam disaster. On 9 October 1963, a few weeks before his oath as prime minister, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of

During his premiership, Moro had to face the outcome of one of the most tragic events in Italian republican history, the Vajont Dam disaster. On 9 October 1963, a few weeks before his oath as prime minister, a landslide occurred on Monte Toc, in the province of Pordenone

Pordenone (; Venetian language, Venetian and ) is a city and (municipality) in the Italy, Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the capital of the Province of Pordenone, Regional decentralization entity of Pordenone.

The name comes from Lati ...

. The landslide caused a megatsunami

A megatsunami is an incredibly large wave created by a substantial and sudden displacement of material into a body of water.

Megatsunamis have different features from ordinary tsunamis. Ordinary tsunamis are caused by underwater tectonic activi ...

in the artificial lake in which 50 million cubic metres of water overtopped the dam in a wave of , leading to the complete destruction of several villages and towns, and 1,917 deaths. In the previous months, the Adriatic Society of Electricity (SADE) and the Italian government, which both owned the dam, dismissed evidence and concealed reports describing the geological instability of Monte Toc on the southern side of the basin and other early warning signs reported prior to the disaster.

Immediately after the disaster, government and local authorities insisted on attributing the tragedy to an unexpected and unavoidable natural event. Numerous warnings, signs of danger, and negative appraisals had been disregarded in the previous months and the eventual attempt to safely control the landslide into the lake by lowering its level came when the landslide was almost imminent and was too late to prevent it. The PCI newspaper '' L'Unità'' was the first to denounce the actions of management and government. The DC accused the PCI of political profiteering from the tragedy, promising to bring justice to the people killed in the disaster.

Differently from Leone, who was his predecessor and became the head of SADE's team of lawyers, Moro acted strongly to condemn the managers of the society. He immediately dismissed the administrative officials who had supervised the construction of the dam.

Coalition crisis and presidential election

president of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

, asked the PSI leader Pietro Nenni to exit from the government majority.

On 16 July 1964, Segni sent the ''Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign poli ...

'' general Giovanni de Lorenzo to a meeting of representatives of DC, in order to deliver a message in case the negotiations around the formation of a new centre-left government would fail. According to some historians, De Lorenzo reported that Segni was ready to give a subsequent mandate to the president of the Senate of the Republic, Cesare Merzagora, and would ask him to form a president's government composed by all the conservative forces in the Italian Parliament

The Italian Parliament () is the national parliament of the Italy, Italian Republic. It is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1861), the Parliament of the Kingd ...

. This attempted coup, which came to be known as the ''Piano Solo

The piano is often used to provide harmonic accompaniment to a voice or other instrument. However, solo

Solo or SOLO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Characters

* Han Solo, a ''Star Wars'' character

* Jacen Solo, a Jedi in the non-canoni ...

'', only became public in 1967 through the investigative reporting of '' L'Espresso''. Ultimately, Moro managed to form another centre-left majority. During the negotiations, Nenni had accepted the downsizing of his reform programs. On 17 July 1964, Moro went to the Quirinal Palace

The Quirinal Palace ( ) is a historic building in Rome, Italy, the main official residence of the President of Italy, President of the Italian Republic, together with Villa Rosebery in Naples and the Tenuta di Castelporziano, an estate on the outs ...

, with the acceptance of the assignment and the list of ministers of his second government.

In August 1964, Segni had a serious cerebral haemorrhage and resigned after a few months. In the 1964 Italian presidential election, which was held in December, Moro and his majority tried to elect a leftist politician at the Quirinal Palace. On the twenty-first round of voting, the leader of the PSDI and former president of the Constituent Assembly, Giuseppe Saragat, was elected with 646 votes out of 963. Saragat was the first left-wing politician to become president of Italy.

Resignation

Despite the opposition by Segni and other prominent rightist members of the DC, the centre-left coalition, the first one for the Italian post-war political life, stayed in power for nearly five years until the 1968 Italian general election, which was characterized by a defeat for DC's centre-left allies. The PSI and PSDI ran in a joint list named Unified Socialist Party (PSU), which lost many votes compared to the previous election, while the PCI gained ground, achieving 30% of votes in the Senate.Dieter Nohlen

Dieter Nohlen (born 6 November 1939) is a German academic and political scientist. He currently holds the position of Emeritus Professor of Political Science in the Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences of the University of Heidelberg. An ex ...

& Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p. 1048 The PSI and PSDI decided to exit from the government and Saragat appointed Leone at the head of the new cabinet composed only by DC members.

Minister of Foreign Affairs

In the 1968 DC congress, Moro yielded the secretariat and passed to internal opposition. On 5 August 1969, he was appointedItalian Minister of Foreign Affairs

The minister of foreign affairs is the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Italy), Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Italy. The office was one of the positions which Italy inherited from the Kingdom of Sardinia where it was the most ancient mi ...

by the then prime minister Mariano Rumor, a position that he also held under the premierships of Emilio Colombo and Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti ( ; ; 14 January 1919 – 6 May 2013) was an Italian politician and wikt:statesman, statesman who served as the 41st prime minister of Italy in seven governments (1972–1973, 1976–1979, and 1989–1992), and was leader of th ...

.

Pro-Arab policies

During his ministry, Moro continued the pro-Arab policy of his predecessor Fanfani. He forcedYasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

to promise not to carry out terrorist attack

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war a ...

s in Italian territory, with a commitment that was known as the Moro pact (''lodo Moro''). The existence of this pact and its validity was confirmed by Bassam Abu Sharif, a long-time leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP; ) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist organization founded in 1967 by George Habash. It has consistently been the second-largest of the groups forming the Palestine Liberation ...

(PFLP). Interviewed by Italian newspapers, such as '' Corriere della Sera'' and ''La Stampa

(English: "The Press") is an Italian daily newspaper published in Turin with an average circulation of 87,143 copies in May 2023. Distributed in Italy and other European nations, it is one of the oldest newspapers in Italy. Until the late 1970 ...

'', he confirmed the existence of an agreement between Italy and the PFLP, thanks to which the PFLP could "transport weapons and explosives, guaranteeing immunity from attacks in return".

About the pact, Abu Sharif commented: "I personally followed the negotiations for the agreement. Aldo Moro was a great man, a true patriot, who wanted to save Italy some headaches, but I never met him. We discussed the details with an admiral and agents of the Italian secret service. The agreement was defined and since then we have always respected it; we were allowed to organize small transits, passages, and purely Palestinian operations, without involving Italians. After the deal, every time I came to Rome, two cars were waiting for me to protect myself. For our part, we also guaranteed to avoid embarrassment to your country, that is attacks which started directly from the Italian soil." This version was confirmed by former president Francesco Cossiga, who stated that Moro was the real and only creator of the pact. Moro also had to cope with the difficult situation which erupted following the coup by Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

in Libya, a very important country for Italian interests not only for colonial ties but also for its energy resources and the presence of about 20,000 Italians.

1971 presidential election

In the 1971 Italian presidential election, Fanfani was proposed as the DC candidate for the office. His candidacy was weakened by the divisions within his own party and the candidacy of the PSI member Francesco De Martino, who received votes from PCI, PSI, and some PSDI members. Fanfani retired after several unsuccessful ballots and Moro was then proposed as a candidate by the left-wing faction. The right-wing strongly opposed him and the moderate conservative Leone was slightly preferred to him. At the twenty-third round, Leone was finally elected with a centre-right majority, with 518 votes out of 996, including those of the MSI.Italicus Express bombing

On 4 August 1974, a bomb exploded on the Italicus Express, killing 12 people and injuring 48. The train was travelling from Rome toMunich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

; having left Florence about 45 minutes earlier, it was approaching the end of the long San Benedetto Val di Sambro tunnel under the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains ( ; or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; or – a singular with plural meaning; )Latin ''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which would be segmented ''Apenn-inus'', often used with nouns s ...

. The bomb had been placed in the fifth passenger carriage and exploded at 01:23, while the train was reaching the end of the tunnel. The effects of the explosion and subsequent fire would have been even more terrible if the train had remained inside the tunnel. According to what his daughter Maria Fida stated in 2004, Moro should have been on board. A few minutes before departure, he was joined by some officials of the ministry who made him get off to sign some important documents. According to some reconstructions, Moro would have been the real target of the Italicus Express bombing.

Second term as prime minister

In October 1974, Rumor resigned as prime minister after failing to come to an agreement on how to deal with rising economic inflation. In November, Leone gave Moro the task of forming a new cabinet; he was sworn in on 23 November 1974, at the head a cabinet composed by DC and PRI, and externally supported by PSI and PSDI. During Moro's second term as prime minister, the government implemented a series of other important social reforms. A bill, approved on 3 June 1975, introduced various changes for pensioners.Osimo Treaty

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

, defining the official partition of the Free Territory of Trieste. The port city of Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

with a narrow coastal strip to the northwest (Zone A) was given to Italy, while a portion of the north-western part of the Istrian peninsula (Zone B) was given to Yugoslavia. The Italian government was harshly criticized for signing the treaty, particularly for the secretive way in which negotiations were carried out, skipping the traditional diplomatic channels. Since Istria had been an ancient Italian region, dating back to Roman Italy

Roman Italy is the period of ancient Italian history going from the founding of Rome, founding and Roman expansion in Italy, rise of ancient Rome, Rome to the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire; the Latin name of the Italian peninsula ...

, together with the Venetian region of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, as '' Venetia et Histria'', Italian nationalists of the MSI rejected the idea of giving it up.

Between World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the end of World War II, Istria had belonged to Italy for twenty-five years, and the west coast of Istria had long had a sizeable Italian minority population. Some nationalist politicians called for the prosecution of Moro and Rumor, his long-time friend who was the then foreign affairs minister, for the crime of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, as stated in Article 241 of the Italian Criminal Code, which mandated a life sentence for anybody found guilty of aiding and abetting a foreign power to exert its sovereignty on the national territory.

Resignation

Despite the tensions within the government's majority, the close relations between Moro and the PCI leaderEnrico Berlinguer

Enrico Berlinguer (; 25 May 1922 – 11 June 1984) was an Italian politician and statesman. Considered the most popular leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), he led the PCI as the national secretary from 1972 until his death during a te ...

guaranteed a certain stability to Moro's governments, allowing them a capacity to act that went beyond the premises that had seen them born. The fourth Moro government, with Ugo La Malfa as Deputy Prime Minister of Italy, started the first dialogue with the PCI, with the aim of beginning a new phase to strengthen the Italian democratic system. In 1976, the PSI secretary Francesco De Martino withdrew the external support to the government and Moro was forced to resign.

Historic compromise

After the 1976 Italian general election, the PCI gained a historic 34% votes and Moro became a vocal supporter of the necessity of starting a dialogue between DC and PCI. Moro's main aim was to widen the democratic base of the government, including the PCI in the parliamentary majority, in which the cabinets should have been able to represent a larger number of voters and parties. According to him, the DC should have been at the centre of a coalition system based on the principles of consociative democracy. This process was known as Historic Compromise.

Between 1976 and 1977, Berlinguer's PCI broke with the

After the 1976 Italian general election, the PCI gained a historic 34% votes and Moro became a vocal supporter of the necessity of starting a dialogue between DC and PCI. Moro's main aim was to widen the democratic base of the government, including the PCI in the parliamentary majority, in which the cabinets should have been able to represent a larger number of voters and parties. According to him, the DC should have been at the centre of a coalition system based on the principles of consociative democracy. This process was known as Historic Compromise.

Between 1976 and 1977, Berlinguer's PCI broke with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, implementing, together with the Spanish and French Communist parties, a new political theory and strategy known as Eurocommunism. Such a move made eventual cooperation more acceptable for DC voters, and the two parties began an intense parliamentary debate in a moment of deep social crises. In 1977, Moro was personally involved in international disputes. He strongly defended Rumor during the parliamentary debate on the Lockheed scandal, and some journalists reported that Moro himself might have been involved in the bribery. The allegation, with the aim of politically destroying Moro and avoiding the risk of a DC–PCI–PSI cabinet, failed when Moro was cleared on 3 March 1978, thirteen days before his kidnapping.

The early 1978 proposal by Moro of starting a cabinet composed of DC and PSI members, externally supported by the PCI was strongly opposed by both superpowers of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

era. The United States feared that the cooperation between PCI and DC might have allowed the PCI to gain information on strategic NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

military plans and installations. Moreover, the participation in the government of communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

in a Western country would have represented a cultural failure for the United States. On the other hand, the Soviets considered the potential participation by the PCI in a cabinet as a form of emancipation from Moscow and rapprochement to the Americans.

Kidnapping and death

On 16 March 1978, on via Fani, in Rome, a unit of the militant far-left organization known as

On 16 March 1978, on via Fani, in Rome, a unit of the militant far-left organization known as Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( , often abbreviated BR) were an Italian far-left Marxist–Leninist militant group. It was responsible for numerous violent incidents during Italy's Years of Lead, including the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro in 1978, ...

(BR) blocked the two-car convoy that was carrying Moro and kidnapped him, murdering his five bodyguards. On the day of his kidnapping, Moro was on his way to a session of the Chamber of Deputies, where a discussion was to take place regarding a vote of confidence for a new government led by Andreotti, that would for the first time have the support of the PCI. It was to be the first implementation of Moro's strategic political vision. Additionally, he was considered to be the frontrunner for the 1978 Italian presidential election.

In the following days, trade unions called for a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

, while security forces made hundreds of raids in Rome, Milan, Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, and other cities searching for Moro's location, as places linked to Moro and the kidnapping became centres of minor pilgrimage. An estimated 16 million Italians took part in the mass public demonstrations. After a few days, even Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding John XXII ...

, a close friend of Moro's, intervened, offering himself in exchange for Moro. Despite the 13,000 police officers mobilized, 40,000 house searches, and 72,000 roadblocks, the police did not carry out any arrests.

The event has been compared to the assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Kennedy was in the vehicle with his wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onas ...

, and referred to as Italy's 9/11. Although Italy was not the sole European country to experience terrorism, the list including France, Germany, Ireland, and Spain, the murder of Moro was the apogee of Italy's Years of Lead. Many details of Moro's kidnapping remain heavily disputed and unknown. This has led to the promotion of a number of alternative theories about the events, including conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

, which remain popular in Italy, where the judicial truth, which attributes responsibility for the operation exclusively to the Red Brigades, has failed to take root in the collective memory of Italians. Alternative theories gained traction with the institution of a special inquiring committee by the Italian Parliament in 2014 that concluded its operations in 2018. The committee concluded that the judicial truth was produced on the basis of the confession of the terrorist Valerio Morucci and that other evidence which contradicted his version was downplayed. Among these, other witness testimonies indicated that more than four people fired at Moro's convoy, multiple sources report that Moro was held captive in the apartment of Via Massimi 91 in Rome (a property of IOR), and then in Villa Odescalchi on the coast of Palo Laziale, and not in Via Camillo Montalcini 8. In August 2020, about sixty individuals from the world of historical research and political inquiry signed a document denouncing the growing weight that the conspiratorial view on the kidnapping and killing of Moro has in public discourse.

Negotiations and captivity letters

The Red Brigades proposed exchanging Moro's life for the freedom of several prisoners. There has been speculation that during his detention many government officials, including the then interior minister Francesco Cossiga, knew where he was being held. Italian politicians were divided into two factions: one favourable to negotiation (''linea del negoziato'') and the other totally opposing the idea of a negotiated settlement (''linea della fermezza''). The government immediately took a hardline position, namely that the state must not bend to terrorist demands. This position was openly criticized by prominent DC party members, such as Amintore Fanfani and Giovanni Leone, who at the time was serving as president of Italy. All major political forces followed this hardline stance. This included the PCI, which supported democracy and was part of the Italian Parliament; the PCI was accused by the Red Brigades of being a pawn of the bourgeoisie. Exceptions were theItalian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

led by Bettino Craxi

Benedetto "Bettino" Craxi ( ; ; ; 24 February 1934 – 19 January 2000) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from 1976 to 1993, and the 45th Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from 1 ...

and the extra-parliamentary left.

On 2 April 1978, Romano Prodi

Romano Prodi (; born 9 August 1939) is an Italian politician who served as President of the European Commission from 1999 to 2004 and twice as Prime Minister of Italy, from 1996 to 1998, and again from 2006 to 2008. Prodi is considered the fo ...

, Mario Baldassarri, and Alberto Clò, three professors of the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

, passed on a tip about a safe-house where the Red Brigades might be holding Moro. Prodi stated he had been given the tip by the DC founders from beyond the grave in a séance

A séance or seance (; ) is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word ''séance'' comes from the French language, French word for "session", from the Old French , "to sit". In French, the word's meaning is quite general and mundane: one ma ...

through the use of a Ouija board, which gave the names of Viterbo

Viterbo (; Central Italian, Viterbese: ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in the Lazio region of Italy, the Capital city, capital of the province of Viterbo.

It conquered and absorbed the neighboring town of Ferento (see Ferentium) in ...

, Bolsena

Bolsena is a town and ''comune'' of Italy, in the province of Viterbo in northern Lazio on the eastern shore of Lake Bolsena. It is 10 km (6 mi) north-north west of Montefiascone and 36 km (22 mi) north-west of Viterbo. The an ...

, and Gradoli. During the investigation of Moro's kidnapping, some members of law enforcement in Italy and of the secret services advocated for the use of torture against terrorists; prominent military members and generals, such as Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa, were against this. Dalla Chiesa once stated: "Italy is a democratic country that could allow itself the luxury of losing Moro, utnot of the introduction of torture."

During his kidnapping, Moro wrote several letters to the DC leaders and to Pope Paul VI. Some of those letters, including one that was very critical of Andreotti, were kept secret for more than a decade and published only in the early 1990s. In his letters, Moro said that the state's primary focus should be saving lives and that the government should comply with his kidnappers' demands. Most of the DC's leaders argued that the letters did not express Moro's genuine wishes, arguing they were written under duress, and thus refused all negotiations. This position was held in stark contrast to the requests of Moro's family. In his appeal to the terrorists, Pope Paul VI asked them to release Moro "without conditions". The specified "without conditions" is controversial; according to some sources, it was added to Paul VI's letter against his will, and that the Pope wanted to negotiate with the kidnappers to secure the safety of Moro. According to Antonio Mennini, Pope Paul VI had saved ₤10 billion to pay a ransom in order to save Moro.

Murder

When it became clear that the government would continue to refuse to negotiate, the Red Brigades held a summary trial, known as "the people's trial", in which Moro was found guilty and sentenced to death. They then sent a last demand to the Italian authorities, stating that if 16 Red Brigades prisoners were not released, Moro would be killed. The Italian authorities responded with a large-scale manhunt, which was unsuccessful. On 7 May 1978, Moro sent a farewell letter to his wife. He wrote: "They have told me that they are going to kill me in a little while, I kiss you for the last time." On 9 May 1978, after 55 days of captivity, the terrorists placed Moro in a car and told him to cover himself with a blanket, saying that they were going to transport him to another location. After Moro was covered, they shot him ten times. According to the official reconstruction after a series of trials, the killer was Mario Moretti. Moro's body was left in the trunk of a red Renault 4 on Via Michelangelo Caetani towards theTiber River

The Tiber ( ; ; ) is the List of rivers of Italy, third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the R ...

near the Roman Ghetto. After the recovery of Moro's body, Cossiga resigned as interior minister. Pope Paul VI personally officiated at Moro's funeral mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

.

New theories, revelations, and controversies

On 23 January 1983, an Italian court sentenced 32 members of the BR to life imprisonment for their role in the kidnapping and murder of Moro, among other crimes. Many elements and facts have never been fully cleared up, despite a series of trials, and this led to a number of other alternative theories about the events to become popularized. In 1993, historian expressed doubts about what was said by the Mafia ''pentiti'' in relation to the Moro affair because, comparing the two memorials (the amputee of 1978 and the complete of 1990), he said that Moro's allegations addressed to Andreotti were the same, so Andreotti had no interest to order the murder of Carmine Pecorelli, who could not threaten him to publish things already known and publicly available. Andreotti underwent a trial for his role in the assassination of Pecorelli. He was acquitted in the first instance trial (1999), convicted in the second (2002), and acquitted by Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation (2003). In a 2012 interview with Ulisse Spinnato Vega of Agenzia Clorofilla, the BR co-founders Alberto Franceschini andRenato Curcio

Renato Curcio (; born 23 September 1941) is the former leader of the Italian far-left terrorist organization Red Brigades (''Brigate Rosse''), responsible among other facts of the kidnapping and murder of the former Italian prime minister Aldo M ...

remembered Pecorelli. Franceschini stated: "Pecorelli, before dying, said that both the United States and the Soviet Union wanted Moro's death." Additionally, that Moro was suffering from Stockholm syndrome was questioned by the two reports of the Italian Parliament's inquiry about the Moro affair. According to this view, Moro was at the height of his faculties, he was very recognizable, and at some point it was him who was leading the negotiation for his own liberation and salvation. This position was supported by Leonardo Sciascia, who discussed it in the minority report he signed as a member of the first parliamentary commission and in his book ''L'affaire Moro''.

In 2005, Sergio Flamigni, a leftist politician and writer who had served on a parliamentary inquiry on the Moro case, suggested the involvement of the Operation Gladio

Operation Gladio was the codename for clandestine " stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU; founded in 1948), and subsequently by NATO (formed in 1949) and by the CIA (established in 1947), in ...

network directed by NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

. He asserted that Gladio had manipulated Moretti as a way to take over the Red Brigades to effect a strategy of tension aimed at creating popular demand for a new, right-wing law-and-order regime. In 2006, Steve Pieczenik was interviewed by Emmanuel Amara in his documentary film ''Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro'' ("The Last Days of Aldo Moro"). In the interview, Pieczenik, a conspiracy theorist, and expert on international terrorism and negotiating strategies who had been brought to Italy as a consultant to Cossiga's Crisis Committee, stated: "We had to sacrifice Aldo Moro to maintain the stability of Italy."Emmanuel Amara, ''Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro'' (''The Last Days of Aldo Moro'')Interview of Steve Pieczenik put on-line

by Rue 89Hubert Artus

Pourquoi le pouvoir italien a lâché Aldo Moro, exécuté en 1978

(Why the Italian Power let go of Aldo Moro, executed in 1978), '' Rue 89'', 6 February 2008 Pieczenik maintained that the United States had to "instrumentalize the Red Brigades". According to him, the decision to have Moro killed was taken during the fourth week of his detention, when Moro was thought to be revealing state secrets in his letters, namely the existence of Gladio. In another interview, Cossiga revealed that the Crisis Committee had also leaked, in a form of black propaganda, a false statement attributed to the Red Brigades that Moro was already dead. This was intended to communicate to the kidnappers that further negotiations would be useless since the government had written Moro off.

Legacy

As a Christian democrat with social-democratic tendencies, Moro is widely considered one of the ideological fathers of modern Italian centre-left, having led the first centre-left government in the history of the Italian Republic, the Organic centre-left. He was the leading figure of the left wing of the DC, which he steered towards the left as the party's secretary-general from 1959 to 1964. While he was prime minister, a

As a Christian democrat with social-democratic tendencies, Moro is widely considered one of the ideological fathers of modern Italian centre-left, having led the first centre-left government in the history of the Italian Republic, the Organic centre-left. He was the leading figure of the left wing of the DC, which he steered towards the left as the party's secretary-general from 1959 to 1964. While he was prime minister, a land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

was implemented in 1964; it has been described as the first step towards abolishing sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement in which a landowner allows a tenant (sharecropper) to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land. Sharecropping is not to be conflated with tenant farming, providing the tenant a ...

. Landless tenants were given cheap credit in order to allow them to own the land. Economically, Moro's policies are seen as a response to socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

influence. Although central planning

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

instruments were never used, a five-year economic programme was established in 1965.

During his political life, Moro implemented numerous reforms that deeply changed Italian social life; along with his long-time friend and at the same time opponent, Amintore Fanfani, he was the protagonist of a long-standing political phase, which brought the DC towards more left-wing politics through a cooperation with the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

first and the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

later. Due to his reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

stances but also for his tragic death, Moro has often been compared to John F. Kennedy and Olof Palme

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (; ; 30 January 1927 – 28 February 1986) was a Swedish politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 1969 to 1976 and 1982 to 1986. Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 until as ...

.

According to media reports on 26 September 2012, the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

received a file on beatification

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the p ...

for Moro; this is the first step to becoming a saint in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. In April 2015, it was reported that the process of beatification might be suspended or closed following the recent controversies. The postulator stated that the process would continue when the discrepancies were cleared up. The halting of proceedings was due to Mennini, the priest who heard his last confession, being allowed to provide a statement to a tribunal in regards to Moro's kidnapping and confession. Following this, the beatification process was resumed.

In January 2022, a note claiming responsibility for the abduction of Moro was auctioned despite widespread condemnation.

Electoral history

Cinematic adaptations

A number of films have portrayed the events of Moro's kidnapping and murder with varying degrees of fictionalization. They include the following: * ''Todo modo'' (1976), directed by Elio Petri, based on a novel by Leonardo Sciascia, and made before Moro's kidnapping. * '' Il caso Moro'' (1986), directed byGiuseppe Ferrara

Giuseppe Ferrara (15 July 1932 – 25 June 2016) was an Italian film director and screenwriter.

and starring Gian Maria Volonté as Moro.

* '' Year of the Gun'' (1991), directed by John Frankenheimer

John Michael Frankenheimer (February 19, 1930 – July 6, 2002) was an American film and television director known for social dramas and action/suspense films. Among his credits are ''Birdman of Alcatraz (film), Birdman of Alcatraz'', ''The Manc ...

.

* ''Broken Dreams'' (''Sogni infranti'', 1995), a documentary directed by Marco Bellocchio

Marco Bellocchio (; born 9 November 1939) is an Italian film director, screenwriter, and actor.

Life and career

Born in Bobbio, near Piacenza, Marco Bellocchio had a strict Catholic upbringing – his father was a lawyer, his mother a schooltea ...

.

* ''Five Moons Plaza'' (''Piazza Delle Cinque Lune'', 2003), directed by Renzo Martinelli and starring Donald Sutherland

Donald McNichol Sutherland (17 July 1935 – 20 June 2024) was a Canadian actor. With a career spanning six decades, he received List of awards and nominations received by Donald Sutherland, numerous accolades, including a Primetime Emmy Award ...

.

* '' Good Morning, Night'' (''Buongiorno, notte'', 2003), directed by Marco Bellocchio, portrays the kidnapping largely from the perspective of one of the kidnappers.

* '' Romanzo Criminale'' (2005), directed by Michele Placido

Michele Placido (; born 19 May 1946) is an Italian actor, director and screenwriter. He began his career on stage, and first gained mainstream attention through a series of roles in films directed by the likes of Mario Monicelli and Marco Belloc ...

, portrays the authorities finding Moro's body.

* ''Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro'' (''The Last Days of Aldo Moro'', 2006).

* '' Il Divo (2008): La Straordinaria vita di Giulio Andreotti'', directed by Paolo Sorrentino

Paolo Sorrentino (; ; born 31 May 1970) is an Italian film director, screenwriter, and writer. He is considered one of the most prominent filmmakers of Italian cinema working today. He is known for visually striking and complex dramas and has of ...

, highlighting the responsibility of Andreotti.

* '' Piazza Fontana: The Italian Conspiracy'' (''Romanzo di una strage'', 2012), directed by Marco Tullio Giordana

Marco Tullio Giordana (born 1 October 1950) is an Italian film director and screenwriter.

Biography

Born in Milan, during the 1970s he approached the cinema by collaborating on the screenplay of Roberto Faenza's 1977 documentary ''Forza Itali ...

, with Moro portrayed by actor Fabrizio Gifuni.

* '' Exterior Night'' (2022), also directed by Marco Bellocchio, with Fabrizio Gifuni repeating cast as Moro. Released as a film and a six-part miniseries, it was awarded at the 35th European Film Awards and the São Paulo International Film Festival

The São Paulo International Film Festival (), also known internationally as Mostra, is an annual film festival held in the city of São Paulo, Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South Ame ...

.

See also

* List of secretaries of the Christian Democracy * Propaganda Due – Italian criminal secret organization that opposed Moro's Historic Compromise * La Cagoule – far-right criminal organization that committed acts of terrorism to inculpate the political leftReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Ma la verità vera ancora non c'è

– interview with Giovanni Moro (Aldo Moro's son) at ''

La Repubblica

(; English: "the Republic") is an Italian daily general-interest newspaper with an average circulation of 151,309 copies in May 2023. It was founded in 1976 in Rome by Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso (now known as GEDI Gruppo Editoriale) and l ...

'' (in Italian), 16 March 1998.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moro, Aldo

1916 births

European politicians assassinated in the 1970s

1978 deaths

Assassinated Italian politicians

Christian Democracy (Italy) politicians

Deaths by firearm in Italy

Deaths related to the Years of Lead (Italy)

Deputies of Legislature I of Italy

Deputies of Legislature II of Italy

Deputies of Legislature III of Italy

Deputies of Legislature IV of Italy

Deputies of Legislature V of Italy

Deputies of Legislature VI of Italy

Deputies of Legislature VII of Italy

Education ministers of Italy

Ministers of foreign affairs of Italy

Italian Roman Catholics

Lay Dominicans

Italian military personnel of World War II

Italian terrorism victims

Kidnapped Italian people

Kidnapped politicians

Members of the Constituent Assembly of Italy

Missing person cases in Italy

People from Maglie

People murdered in Lazio

Politicians of Apulia

Pope Paul VI

Prime ministers of Italy

Politicians assassinated in 1978

Formerly missing Italian people