Afroyim V on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Afroyim v. Rusk'', 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a

''Afroyim v. Rusk'', 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a

In the

In the

The official

The official

The minority—in a dissent written by Associate Justice

The minority—in a dissent written by Associate Justice

The phrase ''"voluntarily performing any of the following acts with the intention of relinquishing United States nationality"'' was added in 1986, and various other changes have been made over time to the list of expatriating acts; se

notes

The concept of dual citizenship, which previously had been strongly opposed by the U.S. government, has become more accepted in the years since ''Afroyim''. In 1980, the administration of President

"Afroyim v. Rusk: The Evolution, Uncertainty and Implications of a Constitutional Principle".

''

Oyez

{{DEFAULTSORT:Afroyim V. Rusk 1967 in United States case law History of immigration to the United States United States Citizenship Clause case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court decisions that overrule a prior Supreme Court decision United States Supreme Court cases of the Warren Court Denaturalization case law United States immigration and naturalization case law

''Afroyim v. Rusk'', 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a

''Afroyim v. Rusk'', 387 U.S. 253 (1967), was a landmark decision

Landmark court decisions, in present-day common law legal systems, establish precedents that determine a significant new legal principle or concept, or otherwise substantially affect the interpretation of existing law. "Leading case" is commonly ...

of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

, which ruled that citizens of the United States may not be deprived of their citizenship involuntarily. The U.S. government had attempted to revoke the citizenship of Beys Afroyim, a man born in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, because he had cast a vote in an Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

i election after becoming a naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

U.S. citizen. The Supreme Court decided that Afroyim's right to retain his citizenship was guaranteed by the Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted on July 9, 1868, which states:

This clause reversed a portion of the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' decision, which had ...

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. In so doing, the Court struck down a federal law mandating loss of U.S. citizenship for voting in a foreign election—thereby overruling one of its own precedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

s, '' Perez v. Brownell'' (1958), in which it had upheld loss of citizenship under similar circumstances less than a decade earlier.

The ''Afroyim'' decision opened the way for a wider acceptance of dual (or multiple) citizenship in United States law.Spiro (2005), p. 147. "Plural citizenship ... may come to be the mark of globalization, as state-based allegiances today diminish in importance relative to other affiliations. The Supreme Court's 1967 decision in ''Afroyim v. Rusk'' supplies an early glimpse of the transition.... ''Afroyim'' opened the door to the maintenance of multiple active national ties. It is to ''Afroyim'' that one can trace the genesis of the late modern edition of American citizenship, a version less jealous of alternative attachments." The Bancroft Treaties

The Bancroft treaties, also called the Bancroft conventions, were a series of agreements made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries between the United States and other countries. They recognized the right of each party's nationals to become ...

—a series of agreements between the United States and other nations which had sought to limit dual citizenship following naturalization—were eventually abandoned after the Carter administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 39th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Jimmy Carter, his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democratic Party ...

concluded that ''Afroyim'' and other Supreme Court decisions had rendered them unenforceable.

The impact of ''Afroyim v. Rusk'' was narrowed by a later case, '' Rogers v. Bellei'' (1971), in which the Court determined that the Fourteenth Amendment safeguarded citizenship only when a person was born or naturalized in the United States, and that Congress retained authority to regulate the citizenship status of a person who was born outside the United States to an American parent. However, the specific law at issue in ''Rogers v. Bellei''—a requirement for a minimum period of U.S. residence that Bellei had failed to satisfy—was repealed by Congress in 1978. As a consequence of revised policies adopted in 1990 by the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy of the United State ...

, it is now (in the words of one expert) "virtually impossible to lose American citizenship without formally and expressly renouncing it."

Background

Early history of United States citizenship law

Citizenship in the United States

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constitu ...

has historically been acquired in one of three ways: by birth in the United States (''jus soli

''Jus soli'' ( or , ), meaning 'right of soil', is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship. ''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contrast to ''jus sanguinis'' ('right of blood') ass ...

'', "right of the soil"); by birth outside the United States to an American parent (''jus sanguinis

( or , ), meaning 'right of blood', is a principle of nationality law by which nationality is determined or acquired by the nationality of one or both parents. Children at birth may be nationals of a particular state if either or both of thei ...

'', "right of the blood"); or by immigration to the United States

Immigration to the United States has been a major source of population growth and Culture of the United States, cultural change throughout much of history of the United States, its history. As of January 2025, the United States has the la ...

followed by naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

.

In 1857, the Supreme Court held

Held may refer to:

Places

* Held Glacier

People Arts and media

* Adolph Held (1885–1969), U.S. newspaper editor, banker, labor activist

*Al Held (1928–2005), U.S. abstract expressionist painter.

*Alexander Held (born 1958), German television ...

in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' that African slaves, former slaves, and their descendants were not eligible to be citizens. After the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

(1861–65) and the resulting abolition of slavery in the United States, steps were taken to grant citizenship to the freed slaves. Congress first enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Ame ...

, which included a clause declaring "all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power" to be citizens. Even as the Civil Rights Act was being debated in Congress, its opponents argued that the citizenship provision was unconstitutional

In constitutional law, constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applic ...

. In light of this concern, as well as to protect the new grant of citizenship for former slaves from being repealed by a later Congress, the drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution included a Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted on July 9, 1868, which states:

This clause reversed a portion of the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' decision, which had ...

, which would entrench in the Constitution (and thereby set beyond the future reach of Congress or the courts) a guarantee of citizenship stating that "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States". The Fourteenth Amendment—including the Citizenship Clause—was ratified by state legislatures and became a part of the Constitution in 1868.

Loss of United States citizenship

The Constitution does not specifically deal with loss of citizenship. An amendment proposed by Congress in 1810—the Titles of Nobility Amendment—would, if ratified, have provided that any citizen who accepted any "present, pension, office or emolument" from a foreign country, without the consent of Congress, would "cease to be a citizen of the United States"; however, this amendment was never ratified by a sufficient number of state legislatures and, as a result, never became a part of the Constitution. In the

In the Expatriation Act of 1868

The Expatriation Act of 1868 was an act of the 40th United States Congress that declared, as part of the United States nationality law, that the right of expatriation (i.e. a right to renounce one's citizenship) is "a natural and inherent ...

, Congress declared that individuals born in the United States had an inherent right to expatriation

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country.

The term often refers to a professional, skilled worker, or student from an affluent country. However, it may also refer to retirees, artists and ...

(giving up of citizenship), it has historically been accepted that certain actions could result in loss of citizenship. The possibility of this was noted by the Supreme Court in '' United States v. Wong Kim Ark'', an 1898 case involving the citizenship of a man born in the United States to Chinese parents who were legally domiciled in the country. After ruling in this case that Wong was born a U.S. citizen despite his Chinese ancestry, the Court went on to state that his birthright citizenship " adnot been lost or taken away by anything happening since his birth." By making this statement, the Supreme Court affirmed that Wong had not done anything to result in the loss of United States citizenship, therefore acknowledging that there were actions that could result in the loss of citizenship.

The Nationality Act of 1940

The Nationality Act of 1940 (H.R. 9980; Pub.L. 76-853; 54 Stat. 1137) revised numerous provisions of law relating to American citizenship and naturalization. It was enacted by the 76th Congress of the United States and signed into law on Octob ...

provided for loss of citizenship based on foreign military or government service, when coupled with citizenship in that foreign country. This statute also mandated loss of citizenship for desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

from the U.S. armed forces, remaining outside the United States in order to evade military service during wartime, or voting in a foreign election. The provision calling for loss of citizenship for foreign military service was held by the Supreme Court not to be enforceable without proof that said service had been voluntary, in a 1958 case ('' Nishikawa v. Dulles''), and revocation of citizenship as a punishment for desertion was struck down that same year in another case ('' Trop v. Dulles'').

However, in yet another 1958 case ('' Perez v. Brownell),'' the Supreme Court affirmed the provision revoking the citizenship of any American who had voted in an election in a foreign country, as a legitimate exercise (under the Constitution's Necessary and Proper Clause

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, is a clause in Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution:

Since the landmark decision '' McCulloch v. Maryland'', the US Supreme Court has ruled that this clause gr ...

) of Congress' authority to regulate foreign affairs and avoid potentially embarrassing diplomatic situations. Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, the author of the opinion of the Court (supported by a 5–4 majority), wrote that:

In a dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

argued that "Citizenship is man's basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights" and that "a government of the people cannot take away their citizenship simply because one branch of that government can be said to have a conceivably rational basis for wanting to do so." While Warren was willing to allow for loss of citizenship as a result of foreign naturalization or other actions "by which n Americanmanifests allegiance to a foreign state hich

Ij () is a village in Golabar Rural District of the Central District in Ijrud County, Zanjan province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq ...

may be so inconsistent with the retention of .S.citizenship as to result in loss of that status", he wrote that "In specifying that any act of voting in a foreign political election results in loss of citizenship, Congress has employed a classification so broad that it encompasses conduct that fails to show a voluntary abandonment of American citizenship."

Two Supreme Court decisions after ''Perez'' called into question the principle that loss of citizenship could occur even without the affected individual's intent. In '' Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez'' (1963), the Court struck down a law revoking citizenship for remaining outside the United States in order to avoid conscription into the armed forces. Associate Justice William J. Brennan (who had been in the majority in ''Perez'') wrote a separate opinion concurring with the majority in ''Mendoza-Martinez'' and expressing reservations about ''Perez''. In '' Schneider v. Rusk'' (1964), where the Court invalidated a provision revoking the citizenship of naturalized citizens who returned to live permanently in their countries of origin, Brennan recused himself and did not participate in the decision of the case.

Beys Afroyim

Beys Afroyim (born Ephraim Bernstein, 1893–1984) was anartist

An artist is a person engaged in an activity related to creating art, practicing the arts, or demonstrating the work of art. The most common usage (in both everyday speech and academic discourse) refers to a practitioner in the visual arts o ...

and active communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

. Various sources state that he was born in either 1893Spiro (2005), p. 153., painting by Beys Afroyim, exhibited at the Museum of the City of New York. This source says Afroyim was born in 1893, in Riki , Poland. It also states that Afroyim's court case "hinged on his ability to convince the Court that he had never voted in Israel", a claim contradicted by the facts as laid out in the Supreme Court's opinion in ''Afroyim v. Rusk.''The court opinions in Afroyim's case state that he was born in Poland in 1893. ''Afroyim v. Rusk'', 250 F. Supp. 686, 687; 361 F.2d 102, 103; 387 U.S. 253, 254. or 1898, Naturalization record of Ephraim Bernstein, also known as Beys Afroyim. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

(via Ancestry.com

Ancestry.com LLC is an American genealogy company based in Lehi, Utah. The largest for-profit genealogy company in the world, it operates a network of genealogical, historical records, and related genetic genealogy websites. It is owned by The ...

). Retrieved May 8, 2012. This source says Afroyim was born on March 15, 1898, in Riga, Russia, and became a U.S. citizen on June 14, 1926. A letter confirming Afroyim's loss of U.S. citizenship, dated January 13, 1961, accompanies the naturalization record. and either in Poland generally, specifically in the Polish town of Ryki

Ryki is a town in the Lublin Voivodeship in eastern Poland, capital of Ryki County. It has 9,767 inhabitants (as of 2007). It is situated between Warsaw and Lublin. Ryki belongs to Lesser Poland, and historically is part of ''Ziemia Stężycka' ...

, or in Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

(then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

). In 1912, Afroyim immigrated to the United States, and on June 14, 1926, he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen.''Afroyim'', 387 U.S. at 254. He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago, founded in 1879, is one of the oldest and largest art museums in the United States. The museum is based in the Art Institute of Chicago Building in Chicago's Grant Park (Chicago), Grant Park. Its collection, stewa ...

, as well as the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design is an honorary association of American artists, founded in New York City in 1825 by Samuel Morse, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Frederick Styles Agate, Martin E. Thompson, Charles Cushing Wright, Ithiel Town, an ...

in New York City, and he was commissioned to paint portraits of George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalism (literature), naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despi ...

, and Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian and American composer, music theorist, teacher and writer. He was among the first Modernism (music), modernists who transformed the practice of harmony in 20th-centu ...

. In 1949, Afroyim left the United States and settled in Israel, together with his wife and former student Soshana (an Austrian artist).

In 1960, following the breakdown of his marriage, Afroyim decided to return to the United States,Spiro (2005), p. 154. but the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

refused to renew his U.S. passport, ruling that because Afroyim had voted in the 1951 Israeli legislative election

Elections for the second Knesset were held in Israel on 30 July 1951. Voter turnout was 75.1%.Dieter Nohlen, Florian Grotz & Christof Hartmann (2001) ''Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume I'', p123

Results

Aftermath

The second Knesset ...

, he had lost his citizenship under the provisions of the Nationality Act of 1940.''Afroyim'', 387 U.S. at 254. "In 1960, when froyimapplied for renewal of his United States passport, the Department of State refused to grant it on the sole ground that he had lost his American citizenship by virtue of § 401(e) of the Nationality Act of 1940, which provides that a United States citizen shall 'lose' his citizenship if he votes 'in a political election in a foreign state.'" A letter certifying Afroyim's loss of citizenship was issued by the Immigration and Naturalization Service

The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was a United States federal government agency under the United States Department of Labor from 1933 to 1940 and under the United States Department of Justice from 1940 to 2003.

Refe ...

(INS) on January 13, 1961.

Afroyim challenged the revocation of his citizenship. Initially, he claimed that he had not in fact voted in Israel's 1951 election, but had entered the polling place

A polling place is where voters cast their ballots in elections. The phrase polling station is also used in American English, British English and Canadian English although a polling place is the building and polling station is the specific ...

solely in order to draw sketches of voters casting their ballots. Afroyim's initial challenge was rejected in administrative proceedings in 1965. He then sued in federal district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district. Each district covers one U.S. state or a portion of a state. There is at least one feder ...

, with his lawyer agreeing to a stipulation In United States law, a stipulation is a formal legal acknowledgment and agreement made between opposing parties before a pending hearing or trial.

For example, both parties might stipulate to certain facts and so not have to argue them in court. A ...

that Afroyim had in fact voted in Israel, but arguing that the statute under which this action had resulted in his losing his citizenship was unconstitutional. A federal judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (in case citations, S.D.N.Y.) is a federal trial court whose geographic jurisdiction encompasses eight counties of the State of New York. Two of these are in New York Ci ...

rejected Afroyim's claim on February 25, 1966, concluding that "in the opinion of Congress voting in a foreign political election could import 'allegiance to another country' in some measure 'inconsistent with American citizenship'" and that the question of this law's validity had been settled by the Supreme Court's 1958 ''Perez'' decision.''Afroyim'', 387 U.S. at 253 .

Afroyim appealed the district court's ruling against him to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory covers the states of Connecticut, New York, and Vermont, and it has appellate jurisdic ...

, which upheld the lower court's reasoning and decision on May 24, 1966. Two of the three judges who heard Afroyim's appeal found the district court's analysis and affirmation of ''Perez'' to be "exhaustive and most penetrating". "We affirm the judgment f the district courton the authority of Perez v. Brownell.... The exposition by the istrict courtof the present posture of the issues that were decided by the upremeCourt in Perez was exhaustive and most penetrating...." The third judge expressed serious reservations regarding the viability of ''Perez'' and suggested that Afroyim might have obtained a different result if he had framed his case differently, but decided to concur (albeit reluctantly) in the majority's ruling.

Arguments before the Supreme Court

After losing his appeal to the Second Circuit, Afroyim asked the Supreme Court to overrule theprecedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

it had established in ''Perez'', strike down the foreign voting provision of the Nationality Act as unconstitutional, and decide that he was still a United States citizen. Afroyim's counsel argued that since "neither the Fourteenth Amendment nor any other provision of the Constitution expressly grants Congress the power to take away .S.citizenship once it has been acquired ... the only way froyimcould lose his citizenship was by his own voluntary renunciation of it." The Supreme Court agreed to consider Afroyim's case on October 24, 1966 and held oral arguments on February 20, 1967.

The official

The official respondent

A respondent is a person who is called upon to issue a response to a communication made by another. The term is used in legal contexts, in survey methodology, and in psychological conditioning.

Legal usage

In legal usage, this term specificall ...

(defendant) in Afroyim's case on behalf of the U.S. government was Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving secretary of state after Cordell Hull from the ...

, the Secretary of State during the Kennedy and Johnson

Johnson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Johnson (surname), a common surname in English

* Johnson (given name), a list of people

* List of people with surname Johnson, including fictional characters

*Johnson (composer) (1953–2011) ...

administrations (1961–1969). The legal brief

A brief (Old French from Latin ''brevis'', "short") is a written legal document used in various legal adversarial systems that is presented to a court arguing why one party to a particular case should prevail.

In England and Wales (and other Co ...

laying out Afroyim's arguments was written by Nanette Dembitz, general counsel

A general counsel, also known as chief counsel or chief legal officer (CLO), is the chief in-house lawyer for a company or a governmental department.

In a company, the person holding the position typically reports directly to the CEO, and their ...

of the New York Civil Liberties Union

The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) is a civil rights organization in the United States. Founded in November 1951 as the New York affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, it is a not-for-profit, nonpartisan organization with nearly ...

; the government's brief was written by United States Solicitor General

The solicitor general of the United States (USSG or SG), is the fourth-highest-ranking official within the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), and represents the federal government in cases before the Supreme Court of the United States. ...

(and future Supreme Court Associate Justice) Thurgood Marshall

Thoroughgood "Thurgood" Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme C ...

.Spiro (2005), p. 156. The oral arguments in the case were presented by attorneys Edward Ennis—chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is an American nonprofit civil rights organization founded in 1920. ACLU affiliates are active in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The budget of the ACLU in 2024 was $383 million.

T ...

(ACLU)—for Afroyim, and Charles Gordon—general counsel for the INS—for the government.Spiro (2005), pp. 157–158. Afroyim was in New York City at this time, having been granted a visitor's visa in 1965 while his case went through the courts.

Before heading the ACLU, Ennis had served as general counsel for the INS. In his oral argument supporting Afroyim, Ennis asserted that Congress lacked the power to prescribe forfeiture of citizenship, and he sharply criticized the foreign-relations argument under which the ''Perez'' court had upheld loss of citizenship for voting in a foreign election—pointing out, for example, that when a referendum was held in 1935 on the status of the Saar

Saar or SAAR has several meanings:

People Given name

* Sarr Boubacar (born 1951), Senegalese professional football player

* Saar Ganor, Israeli archaeologist

* Saar Klein (born 1967), American film editor

Surname

* Ain Saar (born 1968), E ...

(a region of Germany occupied after World War I by the United Kingdom and France), Americans had participated in the voting without raising any concerns within the State Department at the time.

Gordon did not make a good showing in the ''Afroyim'' oral arguments despite his skill and experience in the field of immigration law, according to a 2005 article on the ''Afroyim'' case by law professor Peter J. Spiro. Gordon mentioned Israeli elections in 1955 and 1959 in which Afroyim had voted—facts which had not previously been presented to the Supreme Court in the attorneys' briefs or the written record of the case—and much of the remaining questioning from the justices involved criticism of Gordon for confusing matters through the last-minute introduction of this new material.

Afroyim's earlier stipulation that he had voted in the 1951 Israeli election—together with an accompanying concession by the government that this was the sole ground upon which it had acted to revoke Afroyim's citizenship—allowed the potential issue of diluted allegiance

An allegiance is a duty of fidelity said to be owed, or freely committed, by the people, subjects or citizens to their state or sovereign.

Etymology

The word ''allegiance'' comes from Middle English ' (see Medieval Latin ', "a liegance"). The ...

through dual citizenship to be sidestepped. Indeed, in 1951 there was no Israeli nationality law

Israel has two primary pieces of legislation governing the requirements for citizenship, the 1950 Law of Return and 1952 Citizenship Law.

Every Jew has the unrestricted right to immigrate to Israel and become an Israeli citizen. Individuals ...

; eligibility to vote in the election that year had been based on residence rather than any concept of citizenship. Although Afroyim had later acquired Israeli citizenship and voted in at least two other elections in his new country, his lawyers were able to avoid discussing this matter and instead focus entirely on whether foreign voting was a sufficient cause for loss of one's U.S. citizenship.

Opinion of the Court

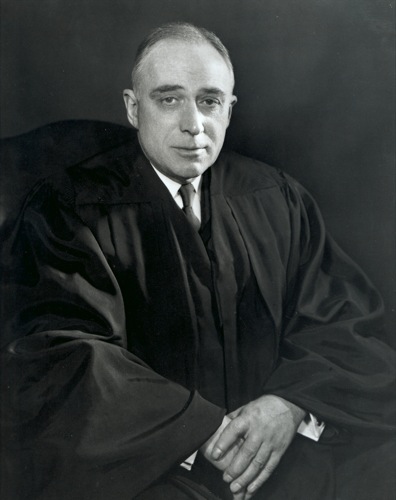

The Supreme Court ruled in Afroyim's favor in a 5–4 decision issued on May 29, 1967. The opinion of the Court—written by Associate JusticeHugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

, and joined by Chief Justice Warren and Associate Justices William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

and Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from Rho ...

—as well as Associate Justice Brennan, who had been part of the majority in ''Perez''—was grounded in the reasoning Warren had used nine years earlier in his ''Perez'' dissent. The court's majority now held that "Congress has no power under the Constitution to divest a person of his United States citizenship absent his voluntary renunciation thereof." Specifically repudiating ''Perez'', the majority of the justices rejected the claim that Congress had any power to revoke citizenship and said that "no such power can be sustained as an implied attribute of sovereignty". Instead, quoting from the Citizenship Clause, Black wrote:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States ... are citizens of the United States...." There is no indication in these words of a fleeting citizenship, good at the moment it is acquired but subject to destruction by the Government at any time. Rather the Amendment can most reasonably be read as defining a citizenship which a citizen keeps unless he voluntarily relinquishes it. Once acquired, this Fourteenth Amendment citizenship was not to be shifted, canceled, or diluted at the will of the Federal Government, the States, or any other governmental unit.The Court found support for its position in the history of the unratified Titles of Nobility Amendment. The fact that this 1810 proposal had been framed as a constitutional amendment, rather than an ordinary act of Congress, was seen by the majority as showing that, even before the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress did not believe that it had the power to revoke anyone's citizenship. The Court further noted that a proposed 1818 act of Congress would have provided a way for citizens to voluntarily relinquish their citizenship, but opponents had argued that Congress had no authority to provide for expatriation. Afroyim's counsel had addressed only the foreign voting question and had carefully avoided any direct challenge to the idea that foreign naturalization might legitimately lead to loss of citizenship (a concept which Warren had been willing to accept in his ''Perez'' dissent). Nevertheless, the Court's ''Afroyim'' ruling went beyond even Warren's earlier position—holding instead that "The very nature of our government makes it completely incongruous to have a rule of law under which a group of citizens temporarily in office can deprive another group of citizens of their citizenship."Spiro (2005), pp. 158–159. In sum Justice Black concluded:

In our country the people are sovereign and the Government cannot sever its relationship to the people by taking away their citizenship. Our Constitution governs us and we must never forget that our Constitution limits the Government to those powers specifically granted or those that are necessary and proper to carry out the specifically granted ones. The Constitution, of course, grants Congress no express power to strip people of their citizenship, whether, in the exercise of the implied power to regulate foreign affairs or in the exercise of any specifically granted power. ..Citizenship is no light trifle to be jeopardized any moment Congress decides to do so under the name of one of its general or implied grants of power. In some instances, loss of citizenship can mean that a man is left without the protection of citizenship in any country in the world -- as a man without a country. Citizenship in this Nation is a part of a cooperative affair. Its citizenry is the country, and the country is its citizenry. The very nature of our free government makes it completely incongruous to have a rule of law under which a group of citizens temporarily in office can deprive another group of citizens of their citizenship. We hold that the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to, and does, protect every citizen of this Nation against a congressional forcible destruction of his citizenship, whatever his creed, color, or race. Our holding does no more than to give to this citizen that which is his own, a constitutional right to remain a citizen in a free country unless he voluntarily relinquishes that citizenship.

Dissent

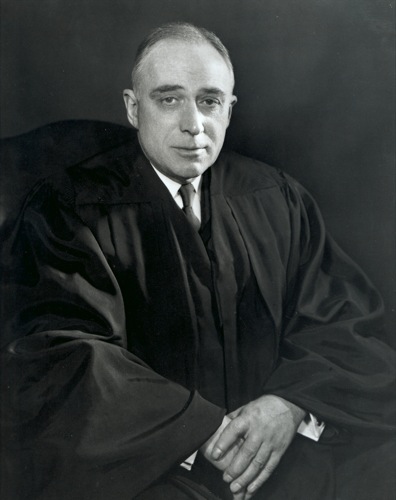

The minority—in a dissent written by Associate Justice

The minority—in a dissent written by Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish hi ...

and joined by Associate Justices Tom C. Clark

Thomas Campbell Clark (September 23, 1899June 13, 1977) was an American lawyer who served as the 59th United States Attorney General, United States attorney general from 1945 to 1949 and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United St ...

, Potter Stewart

Potter Stewart (January 23, 1915 – December 7, 1985) was an American lawyer and judge who was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. During his tenure, he made major contributions to criminal justice reform ...

, and Byron White

Byron Raymond "Whizzer" White (June 8, 1917 – April 15, 2002) was an American lawyer, jurist, and professional American football, football player who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, associate justice of the Supreme ...

—argued that ''Perez'' had been correctly decided, that nothing in the Constitution deprived Congress of the power to revoke a person's citizenship for good cause, and that Congress was within its rights to decide that allowing Americans to vote in foreign elections ran contrary to the foreign policy interests of the nation and ought to result in loss of citizenship. Harlan wrote:

Responding to the assertion that Congress did not have power to revoke a person's citizenship without his or her assent, Harlan predicted that "Until the Court indicates with greater precision what it means by 'assent', today's opinion will surely cause still greater confusion in this area of the law."

Subsequent developments

The ''Afroyim'' decision stated that no one with United States citizenship could be involuntarily deprived of that citizenship. Nevertheless, the Courtdistinguish

In law, to distinguish a case means a court decides the holding or legal reasoning of a precedent case that will not apply due to materially different facts between the two cases. Two formal constraints constrain the later court: the expresse ...

ed a 1971 case, '' Rogers v. Bellei'', holding in this newer case that individuals who had acquired citizenship via ''jus sanguinis

( or , ), meaning 'right of blood', is a principle of nationality law by which nationality is determined or acquired by the nationality of one or both parents. Children at birth may be nationals of a particular state if either or both of thei ...

'', through birth outside the United States to an American parent or parents, could still risk loss of citizenship in various ways, since their citizenship (unlike Afroyim's citizenship) was the result of federal statutes rather than the Citizenship Clause. The statutory provision whereby Bellei lost his citizenship—a U.S. residency requirement which he had failed to satisfy in his youth—was repealed by Congress in 1978; the foreign voting provision, already without effect since ''Afroyim'', was repealed at the same time.A bill to repeal certain sections of title III of the Immigration and Nationality Act, and for other purposes.Public Law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations and affairs between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a state, between different branches of governments, as well as relationships between persons that ...

95-432; 92 Stat. 1046. October 10, 1978.

Although ''Afroyim'' appeared to rule out any involuntary revocation of a person's citizenship, the government continued for the most part to pursue loss-of-citizenship cases when an American had acted in a way believed to imply an intent to give up citizenship—especially when an American had become a naturalized citizen of another country. In a 1980 case, however—''Vance v. Terrazas

''Vance v. Terrazas'', 444 U.S. 252 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established that a United States citizen cannot have their citizenship taken away unless they have acted with an intent to give up that citizenship. Th ...

''—the Supreme Court ruled that intent to relinquish citizenship needed to be proved by itself, and not simply inferred from an individual's having voluntarily performed an action designated by Congress as being incompatible with an intent to keep one's citizenship.Immigration and Nationality Act

The U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act may refer to one of several acts including:

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

* Immigration Act of 1990

The Immigration Act of 1990 () was signed into la ...

, sec. 349; 8 U.S.C.

The United States Code (formally The Code of Laws of the United States of America) is the official codification of the general and permanent federal statutes of the United States. It contains 53 titles, which are organized into numbered se ...

br>sec. 1481The phrase ''"voluntarily performing any of the following acts with the intention of relinquishing United States nationality"'' was added in 1986, and various other changes have been made over time to the list of expatriating acts; se

notes

The concept of dual citizenship, which previously had been strongly opposed by the U.S. government, has become more accepted in the years since ''Afroyim''. In 1980, the administration of President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

concluded that the Bancroft Treaties

The Bancroft treaties, also called the Bancroft conventions, were a series of agreements made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries between the United States and other countries. They recognized the right of each party's nationals to become ...

—a series of bilateral agreements, formulated between 1868 and 1937, which provided for automatic loss of citizenship upon foreign naturalization of a U.S. citizen—were no longer enforceable, due in part to ''Afroyim'', and gave notice terminating these treaties. In 1990, the State Department adopted new guidelines for evaluating potential loss-of-citizenship cases, under which the government now assumes in almost all situations that Americans do not in fact intend to give up their citizenship unless they explicitly indicate to U.S. officials that this is their intention. As explained by Peter J. Spiro, "In the long run, ''Afroyims vision of an absolute right to retain citizenship has been largely, if quietly, vindicated. As a matter of practice, it is now virtually impossible to lose American citizenship without formally and expressly renouncing it."Spiro (2005), p. 163.

While acknowledging that "American citizenship enjoys strong protection against loss under ''Afroyim'' and ''Terrazas''", retired journalist Henry S. Matteo suggested, "It would have been more equitable ... had the Supreme Court relied on the Eighth Amendment, which adds a moral tone as well as a firmer constitutional basis, than the Fourteenth." Matteo also said, "Under ''Afroyim'' there is a lack of balance between rights and protections on one hand, and obligations and responsibilities on the other, all four elements of which have been an integral part of the concept of citizenship, as history shows." Political scientist P. Allan Dionisopoulos wrote that "it is doubtful that any upreme Court decisioncreated a more complex problem for the United States than ''Afroyim v. Rusk''", a decision which he believed had "since become a source of embarrassment for the United States in its relationships with the Arab world" because of the way it facilitated dual U.S.–Israeli citizenship and participation by Americans in Israel's armed forces.

After his Supreme Court victory, Afroyim divided his time between West Brighton (Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

) and the Israeli city of Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

until his death on May 19, 1984, in West Brighton.Obituary of Beys Afroyim. ''Staten Island Advance''. May 20, 1984.

See also

* List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 387 * '' Reid v. Covert'',''Reid v. Covert'', . a Supreme Court case holding that treaties cannot override the ConstitutionNotes

References

* Dionisopoulos, P. Allan (1970–71)."Afroyim v. Rusk: The Evolution, Uncertainty and Implications of a Constitutional Principle".

''

Minnesota Law Review

The ''Minnesota Law Review'' is a student-run law review published by students at University of Minnesota Law School. The journal is published six times a year in November, December, February, April, May, and June. It was established by Henry J. F ...

'' 55:235–257.

*

* Matteo, Henry S. (1997). ''Denationalization v. "The Right to Have Rights": The Standard of Intent in Citizenship Loss''. University Press of America. .

* Spiro, Peter J. (2005). "''Afroyim'': Vaunting Citizenship, Presaging Transnationality". In Martin, David A.; Schuck, Peter H. (2005). ''Immigration Stories''. Foundation Press. pp. 147–168.

External links

* * * Summaries of the case aOyez

{{DEFAULTSORT:Afroyim V. Rusk 1967 in United States case law History of immigration to the United States United States Citizenship Clause case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court decisions that overrule a prior Supreme Court decision United States Supreme Court cases of the Warren Court Denaturalization case law United States immigration and naturalization case law