Aerial Ramming on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aerial ramming or air ramming is the

Aerial ramming or air ramming is the

The first known instance of ramming in air warfare was made over

The first known instance of ramming in air warfare was made over

The

The

On 25 May 1944 Oberfähnrich Hubert Heckmann used his

Avro Project Silver Bug

Military doctrines Air-to-air combat operations and battles Vehicle-ramming attacks Aviation accidents and incidents involving deliberate crashes

Aerial ramming or air ramming is the

Aerial ramming or air ramming is the ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege engine used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus ...

of one aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

with another. It is a last-ditch tactic in air combat

''Air Combat'' is a 1995 Combat flight simulation game, combat flight simulation video game developed and published by Namco for the PlayStation (console), PlayStation, and the first title of the ''Ace Combat'' franchise. Players control an airc ...

, sometimes used when all else has failed. Long before the invention of aircraft, ramming tactics in naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river.

The Military, armed forces branch designated for naval warfare is a navy. Naval operations can be ...

and ground warfare

Land warfare or ground warfare is the process of military operations eventuating in combat that takes place predominantly on the battlespace land surface of the Earth, planet.

Land warfare is categorized by the use of large numbers of combat p ...

were common. The first aerial ramming was performed by Pyotr Nesterov

Pyotr Nikolayevich Nesterov (; – ) was a Russian pilot, aircraft designer and aerobatics pioneer.

Life and career

Nesterov was born on 15 February 1887 in Nizhny Novgorod, into the family of an army officer, a cadet corps teacher. In A ...

in 1914 during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In the early stages of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the tactic was employed by Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

pilots, who called it ''taran (таран)'' , the Russian word for "battering ram".

A ramming pilot could use the weight of the aircraft as a ram, or they could try to make the enemy lose control of their plane, using the propeller or wing to damage the enemy's tail or wing. Ramming took place when a pilot ran out of ammunition yet was still intent on destroying an enemy, or when the plane had already been damaged beyond saving. Most rammings occurred when the attacker's aircraft was economically, strategically or tactically less valuable than the enemy's, such as pilots flying obsolescent aircraft against superior ones, or one man risking his life to kill multiple men. Defending forces resorted to ramming more often than the attackers.

A ramming attack was not considered suicidal in the same manner as ''kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

'' attacks—the ramming pilot stood a chance of surviving, though it was very risky. Sometimes the ramming aircraft itself could survive to make a controlled landing, though most were lost due to combat damage or the pilot bailing out. Ramming was used in air warfare in the first half of the 20th century, in both World War

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

s and in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

. With jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by one or more jet engines.

Whereas the engines in Propeller (aircraft), propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much ...

, as air combat speeds increased, ramming became disused—the probability of successfully executing (and surviving) a ramming attack approached zero. However, the tactic is still possible in modern warfare.

Technique

Three types of ramming attacks were made: * Using the propeller to go in from behind and chop off the tail controls of the enemy aircraft. This was the most difficult to perform, but it had the best chance of survival. * Using the wing to damage the enemy or force a loss of control. Some Soviet aircraft like thePolikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 () is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it is a low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear, and the first such aircraft to attain operational status. It "in ...

had wings strengthened for this purpose.

* Direct ramming using the whole aircraft. This was the easiest but also the most dangerous option.

The first two options were always premeditated but required a high level of piloting skill. The last option might be premeditated or it might be a snap decision made during combat; either way it often killed the attacking pilot.

History

Early concepts

Presaging the 20th century air warfare ramming actions,Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet and playwright.

His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

imagined an apparent aerial attack made by a heavy flying machine with a prominent ram prow against a nearly defenseless lighter-than-air craft in his science fiction work '' Robur the Conqueror'', published in 1886. H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

, writing in 1899 in his novel ''The Sleeper Awakes

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

'', has his main character, Graham, ram one of the enemy's aeroplanes with his flying apparatus, causing it to fall out of the sky. A second enemy machine ceases its attack, afraid of being rammed in turn.

In 1909, the airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

was imagined as an "aerial battleship" by several observers who wrote about the possibility of using an extended ramming pole to attack other airships, and to swing an anchor or other mass on a cable below the airship as a blunt force attack against ground-based targets such as buildings and smokestacks, and against ship masts.

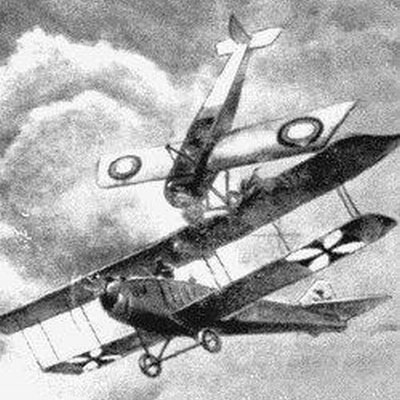

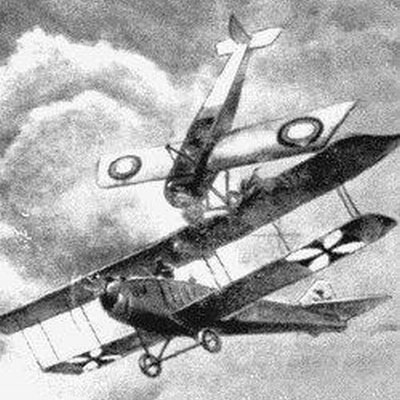

World War I

The first known instance of ramming in air warfare was made over

The first known instance of ramming in air warfare was made over Zhovkva

Zhovkva is a List of cities in Ukraine, city in Lviv Raion, Lviv Oblast (Oblast, region) of western Ukraine. Zhovkva hosts the administration of Zhovkva urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Its population is approximately

History

A ...

by the Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

pilot Pyotr Nesterov

Pyotr Nikolayevich Nesterov (; – ) was a Russian pilot, aircraft designer and aerobatics pioneer.

Life and career

Nesterov was born on 15 February 1887 in Nizhny Novgorod, into the family of an army officer, a cadet corps teacher. In A ...

on 8 September 1914, against an Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n plane.

Nesterov's Morane-Saulnier Type G (s/n 281) and the Austrian Albatros B.II reconnaissance aircraft both crashed in the ramming, killing Nesterov and both occupants of the Austrian aircraft. The second ramming—and the first successful ramming that was not fatal to the attacker—was performed in 1915 by Alexander Kazakov, a flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

and the most successful Russian fighter pilot of World War I. Sgt Arturo Dell'Oro of the Italian 83rd Squadron rammed a two-man Br.C.1 of Flik 45 on 1 September 1917. The American Wilbert Wallace White of the 147th Aero Squadron rammed a German plane on 10 October 1918, and was killed — his opponent survived.

Polish-Soviet War

As the advancingSoviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

Red Army used very few aircraft in Poland, air combat rarely took place (except for interceptions of Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

observation balloons). However, during the course of the war, several Polish pilots, having depleted their ammunition and bombs, attempted to ram Soviet cavalry with their aircraft's undercarriages. This attack allowed an opportunity for an emergency landing, but it almost always ended with the destruction of, or serious damage to, the ramming aircraft.

Spanish Civil War

Ramming was used in theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

. On the night of 27–28 November 1937, Soviet pilot Evgeny Stepanov, flying a Polikarpov I-15

The Polikarpov I-15 () was a Soviet biplane fighter aircraft of the 1930s. Nicknamed ''Chaika'' (', "gull") because of its gulled upper wings,Gunston 1995, p. 299.Green and Swanborough 1979, p. 10. it was operated in large numbers by the Soviet ...

for the Spanish Republican Air Force

The Spanish Republican Air Force was the air arm of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic, the legally established government of Spain between 1931 and 1939. Initially divided into two branches: Military Aeronautics () and Naval Aeron ...

, shot down one SM.81 bomber near Barcelona and emptied the rest of his bullets into another. The second SM.81 continued to fly, so Stepanov resorted to using the left leg of his Chaika's undercarriage to ram the bomber, downing the plane.

World War II

Soviet Union

In World War II, reports of ramming by lone Soviet pilots against the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' became widespread, especially in the early days of the hostilities in the war's Eastern Front. In the first year of the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

, most available Soviet machines were markedly inferior to the German ones and pilots sometimes perceived a ''taran'' as the only way to guarantee the destruction of the enemy. Early Soviet fighter engines were relatively weak, and the underpowered fighters were either fairly well-armed but too slow, or fast but too lightly armed. Lightly armed fighters often expended their ammunition without bringing down the enemy bomber. Very few fighters had radios installed—the pilots had no way to call for assistance and the military expected them to solve problems alone. Trading a single fighter for a multi-engine bomber was considered economically sound. In some cases, pilots who were heavily wounded or in damaged aircraft decided to perform a suicidal attack against air, ground or naval targets. In this instance, the attack becomes more like an unpremeditated ''kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

'' attack (see Nikolai Gastello

Captain Nikolai Frantsevich Gastello (, April 23, 1907 – June 26, 1941) was a Russian aviator and a Hero of the Soviet Union. He is one of the best known Soviet war heroes, being the best known Soviet pilot to conduct a "fire taran" – a suic ...

).

German air tactics early in the war changed in a way that created conditions ripe for ramming attacks. After clearing much of Soviet airpower from their path, the Luftwaffe stopped providing fighter escort for bombing groups, and split their forces into much smaller sorties, including single aircraft making deep penetration flights. One quarter of German aircraft on the Eastern Front had the task of performing strategic or tactical reconnaissance with their '' Aufklärungsgruppe'' units. These reconnaissance or long-range bombing flights were more likely to encounter lone Soviet defenders. Soviet group tactics did not include ''taran'', but Soviet fighters often sortied singly or in pairs rather than in groups. Soviet pilots were prohibited from performing ''taran'' over enemy-held land, but could ram enemy reconnaissance penetrations over the homeland.

Nine rammings took place on the very first day of the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

, one within the first hour. At 0425 hours on 22 June 1941, Lieutenant Ivan Ivanov supposedly drove his Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 () is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it is a low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear, and the first such aircraft to attain operational status. It "in ...

into the tail of an invading Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany a ...

. Ivanov did not survive but was posthumously awarded the Gold Star medal, Hero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both ...

.

Yekaterina Zelenko on 12 September 1941 supposedly performed a diving ramming attack in her Su-2, which tore a Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

in two as the propeller of her plane hit the German aircraft's tail. She remains the only woman ever alleged to have performed an aerial ramming.

After 1943 more Soviet fighters had radios installed, and Chief Marshall Alexander Novikov

Alexander Alexandrovich Novikov (; – 3 December 1976) was the chief marshal of aviation for the Soviet Air Forces during the Soviet Union's involvement in the World War II, Second World War. Lauded as "the man who has piloted the Red Air F ...

developed air-control techniques to coordinate attacks. The fighters had more powerful engines, and in the last year of battle they carried sufficiently heavy armament. As Soviet air-attack options improved, ramming became a rare occurrence. In 1944, future Air Marshall Alexander Pokryshkin officially discouraged the ''taran'', limiting it to "exceptional instances and as an extreme measure".

Lieutenant Boris Kovzan supposedly survived a record four ramming attacks in the war. Aleksei Khlobystov supposedly made three. Seventeen other Soviet pilots were credited with two successful ramming attacks. According to new research, at least 636 successful ''taran'' attacks were made by Soviets between the beginning of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

and the end of the war.Jaśkiewicz, Łukasz; Matus, Yury. ''Tarany powietrzne w wielkiej wojnie ojczyźnianej w drugim okresie wojny'', "Lotnictwo" 7-8/2017 (in Polish), p.93-97 Of these, 227 pilots were killed during the attack or afterwards (35.7%), 233 landed safely, and the rest bailed out.

As new Soviet fighter designs went into service, ramming was discouraged. The economics had shifted; now the Soviet fighter was roughly equivalent to the German one. By September 1944, orders describing how and when to initiate the ramming attack were removed from training materials.

United Kingdom and Commonwealth

On 18 August 1940,Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force (RAF) in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force ( ...

Sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

Bruce Hancock of No.6 SFTS from RAF Windrush used his Avro Anson

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engine, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), R ...

aircraft to ram a Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany a ...

P; there were no survivors.

On the same day Flight Lieutenant James Eglington Marshall of No. 85 Squadron RAF used his Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

to ram the tail unit of a Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany a ...

after he had expended the last of his ammunition on it. The Hurricane's starboard wing tip broke off in the attack and the Heinkel was assessed as "probably destroyed".

A significant event took place during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

. Flight Sergeant

Flight sergeant (commonly abbreviated to Flt Sgt, F/Sgt, FSGT or, currently correctly in the RAF, FS) is a senior non-commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and several other air forces which have adopted all or part of the RAF rank structur ...

Ray Holmes

Raymond Towers Holmes (20 August 1914 – 27 June 2005) was a British Royal Air Force Fighter aircraft, fighter aviator, pilot during the Second World War who is best known for an event that occurred during the Battle of Britain. He became famou ...

of No. 504 Squadron RAF used his Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

to destroy a Dornier Do 17

The Dornier Do 17 is a twin-engined light bomber designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Dornier Flugzeugwerke. Large numbers were operated by the ''Luftwaffe'' throughout the Second World War.

The Do 17 was designed during ...

bomber over London by ramming but at the loss of his own aircraft (and almost his own life) in one of the defining moments of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

. Holmes, making a head-on attack, found his guns inoperative. He flew his plane into the top-side of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

bomber, cutting off the rear tail section with his wing and causing the bomber to dive out of control and crash. Its pilot, Oberleutnant Robert Zehbe, bailed out, only to die later of wounds suffered during the attack, while the injured Holmes bailed out of his plane and survived. Two other crewmen of the Dornier bailed out and survived. As the RAF did not practice ramming as an air combat tactic, this was considered an impromptu manoeuvre, and an act of selfless courage. This event became one of the defining moments of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

and elicited a congratulatory note to the RAF from Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands

Wilhelmina (; Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria; 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962) was List of monarchs of the Netherlands, Queen of the Netherlands from 1890 until her abdication in 1948. She reigned for nearly 58 years, making her the longest- ...

, who had witnessed the event.

On 27 September 1940, Flying Officer

Flying officer (Fg Offr or F/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Flying officer is immediately ...

Percival R. F. Burton (South African) of No. 249 Squadron RAF used his Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

to tear off the tail unit of a Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110, often known unofficially as the Me 110,Because it was built before ''Bayerische Flugzeugwerke'' became Messerschmitt AG in July 1938, the Bf 110 was never officially given the designation Me 110. is a twin-engined (de ...

of V/LG 1. According to eyewitnesses on the ground, Burton deliberately rammed the Bf 110 after a "wildly manoeuvring" chase at rooftop height over Hailsham

Hailsham is a town, a civil parish and the administrative centre of the Wealden district of East Sussex, England.OS Explorer map Eastbourne and Beachy Head Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Dat ...

, England. Burton, Hauptmann Horst Liensberger and Unteroffizier Albert Kopge were all killed when both aircraft crashed just outside town. Burton's Hurricane was found exhausted of ammunition.

On 7 October 1940, Pilot Officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off or P/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Pilot officer is the lowest ran ...

Ken W. Mackenzie of No. 501 Squadron RAF used his Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

to destroy a Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

. His Combat Report read:

I attacked the three nearest machines in vic formation from beneath and a fourth enemy aircraft doing rear-guard flew across the line of fire and he developed a leak in the glycol tank... I emptied the rest of my ammunition into him from 200 yards but he still flew on and down to 80, to 100 feet off the sea. I flew around him and signalled him to go down, which had no result. I therefore attempted to ram his tail with my undercarriage but it reduced my speed too low to hit him. So flying alongside I dipped my starboard wing-tip onto his port tail plane. The tail plane came off and I lost the tip of my starboard wing. The enemy aircraft spun into the sea and partially sank.On 11 November 1940, Flight Lieutenant

Howard Peter Blatchford

Wing commander (rank), Wing Commander Howard Peter "Cowboy" Blatchford (25 February 1912 – 3 May 1943) was a flying ace, who achieved the first Canadians, Canadian victory in World War II.

Blatchford was born in Edmonton, Alberta on 25 Febru ...

(Canadian) of No. 257 Squadron RAF used the propeller of his Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

to attack a Fiat CR.42 near Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-o ...

, England. Blatchford had used up his ammunition during a mêlée with Italian fighters, and upon returning to base discovered two of his propeller blades missing nine inches. Although he did not see the results of his attack and only claimed the Italian fighter as "damaged", he did report splashes of blood on his damaged propeller.

Although technically not ramming, RAF pilots did use an intentional collision of sorts against the V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb ( "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Reich Aviation Ministry () name was Fieseler Fi 103 and its suggestive name was (hellhound). It was also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb or doodlebug a ...

. When it was discovered that shooting a V-1 could detonate the warhead and/or fuel tank, thereby endangering the attacking aircraft, pilots would instead fly beside the V-1. Once in position, the pilot would roll to one side, lifting his wingtip to produce an area of high-pressure turbulence beneath the wingtip of the V-1, causing it to roll in the opposite direction. This tactic was known amongst pilots as ''wing tipping/wing wacking''. The rudimentary automatic pilot

An autopilot is a system used to control the path of a vehicle without requiring constant manual control by a human operator. Autopilots do not replace human operators. Instead, the autopilot assists the operator's control of the vehicle, allow ...

of the V-1 was often not able to compensate, sending it diving into the ground.

Greece

On 2 November 1940,Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

pilot Marinos Mitralexis shot down one Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 ''Sparviero'' (Italian for sparrowhawk) is a three-engined medium bomber developed and manufactured by the Italian aviation company Savoia-Marchetti. It may be the best-known Italian aeroplane of the Second World War. ...

bomber; then, out of ammunition, brought another down by smashing its rudder with the propeller of his PZL P.24 fighter. Both aircraft were forced into emergency landings, and Mitralexis threatened the bomber's four-man crew into surrender using his pistol. Mitralexis was promoted in rank and awarded medals.

Japan

The

The Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

also practised ''tai-atari'' ramming, both by individual initiative and by policy. Individual initiative saw a Nakajima Ki-43

The Nakajima Ki-43 ''Hayabusa'' (, "Peregrine falcon"), formal Japanese designation is a single-engine land-based tactical Fighter aircraft, fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in World War II.

The Allied World War II Allie ...

fighter plane bringing down a lone B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is an American four-engined heavy bomber aircraft developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). A fast and high-flying bomber, the B-17 dropped more bombs than any other aircraft during ...

, ''The Fighting Swede'', on 8 May 1943. After three of the Japanese fighters had each made two attack passes without decisive results, the bomber's pilot, Major Robert N. Keatts, made for the shelter of a nearby rain-squall. Loath to let the bomber escape, Sgt. Tadao Oda executed a head-on ramming attack, known as . Both aircraft crashed with no survivors. Sergeant Oda was posthumously promoted to lieutenant for his sacrifice.

On 26 March 1943, Lieutenant Sanae Ishii of the 64th Sentai used the wing of his Nakajima Ki-43

The Nakajima Ki-43 ''Hayabusa'' (, "Peregrine falcon"), formal Japanese designation is a single-engine land-based tactical Fighter aircraft, fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in World War II.

The Allied World War II Allie ...

to ram the tail of a Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufor ...

, bringing it down over Shwebandaw, Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, killing both Squadron Leader Ivan G. Statham AFC and Pilot Officer Kenneth C. Briffett of 27 Squadron RAF.

On 1 May 1943 Sergeant Miyoshi Watanabe of the 64th Sentai knocked out two engines of a B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

piloted by Robert Kavanaugh, killing two of the bombers crew; he then used his Nakajima Ki-43

The Nakajima Ki-43 ''Hayabusa'' (, "Peregrine falcon"), formal Japanese designation is a single-engine land-based tactical Fighter aircraft, fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in World War II.

The Allied World War II Allie ...

to ram the rear turret of the American bomber after a drawn-out battle over Rangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

. Sergeant Watanabe survived the attack, as did the remaining B-24 crew. Both planes made a forced landing without further loss of life. The crashed B-24 was photographed and appeared in the December 1943 Japanese aviation magazine ''Koku Asahi''. Only three of Kavanaugh's crew survived the war under harsh conditions as POWs.

On 26 October 1943 Corporal Tomio Kamiguchi of the 64th Sentai used his Nakajima Ki-43

The Nakajima Ki-43 ''Hayabusa'' (, "Peregrine falcon"), formal Japanese designation is a single-engine land-based tactical Fighter aircraft, fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in World War II.

The Allied World War II Allie ...

to ram a B-24J Liberator, when his guns failed to fire during a sustained attack lasting over 50 minutes by Ki-43II and Kawasaki Ki-45

The Kawasaki Ki-45 ''Toryu'' (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") is a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation ; the Allied reporting name was "Nick". Originally serving as ...

s of 21st Sentai. The engagement included approximately 50 two-ship passes on the B-24s after they attacked Rangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

. Nearing the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

and already heavily damaged by the other Japanese fighters in the 64th, the bomber, named "Boogie Woogie Bomb Buggy," belonging to the 492nd Bomb Squadron and piloted by 1st Lt. Roy G. Vaughan, crashed in the jungle approaching Gwa Bay. Bombardier 2nd Lt. Gustaf 'Gus' Johnston was the sole survivor of the B-24 and became a POW. Kamiguchi was thrown clear in the impact, parachuted, and also survived. American researcher Matthew Poole notes that Japanese historian Hiroshi Ichimura interviewed 64th Sentai veteran Lt. Naoyuki Ito, who also claimed to have shot down a B-24 of the 492nd BS on 26 October 1943. The B-24 was claimed to have been shot down by two experienced Japanese aces: Lt. Naoyuki Ito and Sgt. Major Takuwa. In addition, Ito stated that 19-year-old green pilot Cpl. Kamiguchi rammed the crippled B-24, and General Major Shinichi Tanaka praised the brave young pilot and intentionally made "Corporal Saw" a legend. Another 64th Sentai veteran, Sgt. Ikezawa, recalled that a sullen Sgt. Major Takuwa said to him "The B-24 was going down. Kamiguchi did not need to ram it!"

I. Hata, Y. Izawa, and C. Shores in ''Japanese Army Air Force Fighter Units and Their Aces 1939–1945'' includes the biography of Capt. Ito of the 64th Sentai which states: “He later transferred to the 3rd Chutai, and was to claim eight victories, including a B-24 over Rangoon on 26 October 1943.” According to Ichimura, Sgt. Maj. Takuwa's account was not included in this source, as only aces with nine or more victories were given a biography in the book.

On 6 June 1944, having expended his ammunition in an extended dogfight, Sergeant Tomesaku Igarashi of the 50th Sentai used the propeller of his Nakajima Ki-43

The Nakajima Ki-43 ''Hayabusa'' (, "Peregrine falcon"), formal Japanese designation is a single-engine land-based tactical Fighter aircraft, fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in World War II.

The Allied World War II Allie ...

to bring down a Lockheed P-38 Lightning

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinc ...

near Meiktila

Meiktila (; ) is a city in central Burma on the banks of Meiktila Lake in the Mandalay Region at the junctions of the Bagan- Taunggyi, Yangon- Mandalay and Meiktila-Myingyan highways. Because of its strategic position, Meiktila is home to Myanm ...

, Burma. After the pilot bailed out, Igarashi attacked him in his parachute. Sergeant Shinobu Ikeda of the 25th Dokuritsu Chutai rammed his Ki-45 into Cpt. Roger Parrish's B-29 "Gallopin Goose" (42-6390) on 7 December over Mukden

Shenyang,; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly known as Fengtian formerly known by its Manchu name Mukden, is a sub-provincial city in China and the provincial capital of Liaoning province. It is the province's most populous city with a p ...

.Mann 2009, p. 67. Sgt. Ikeda and all except one crew member of the B-29 perished.

Starting in August 1944, several Japanese pilots flying Kawasaki Ki-45

The Kawasaki Ki-45 ''Toryu'' (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") is a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation ; the Allied reporting name was "Nick". Originally serving as ...

and other fighters engaging B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined Propeller (aeronautics), propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to ...

es found that ramming the very heavy bomber was a practical tactic. From that experience, in November 1944 a "Special Attack Unit" was formed using Kawasaki Ki-61

The Kawasaki Ki-61 ''Hien'' (飛燕, "flying swallow") is a Japanese World War II fighter aircraft. Used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service, it was designated the "Army Type 3 Fighter" (三式戦闘機). Allied intelligence initially be ...

s that had been stripped of most of their weapons and armor so as to quickly achieve high altitude. Three successful surviving ramming pilots were the first recipients of the '' Bukosho'', Japan's equivalent to the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

or Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

, an award which had been inaugurated on 7 December 1944 as an Imperial Edict by Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

. Membership in the Special Attack Unit was seen as a final assignment; the pilots were expected to perform ramming attacks until death or serious injury stopped their service.

The Japanese practice of kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

may also be viewed as a form of ramming, although the primary mode of destruction was not physical impact force, but rather the explosives carried. Kamikaze was used exclusively against Allied ship targets.

Bulgaria

Two rammings () were performed byBulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

n fighter pilots defending Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

against Allied bombers in 1943 and 1944. The first one was by poruchik ( Senior Lieutenant) Dimitar Spisarevski on 20 December 1943. Flying a Bf 109 G2 fighter, he rammed and destroyed American B-24 Liberator #42-73428 of the 376th Bomb Group, though it is unknown whether the collision was intentional. The Bulgarian military said it was deliberate, and increased his rank posthumously. The second ramming was performed by poruchik Nedelcho Bonchev on 17 April 1944 against an American B-17 Flying Fortress. Bonchev succeeded in bailing out and surviving after the ramming. After the fall of the Third Bulgarian Kingdom 9 September 1944 he went on flying against the Germans. His Bf 109 was shot down during a mission and he was wounded and taken captive. After several months in captivity, he was killed by a female SS guard during a POW march which he could not take, owing to his critical health condition.

Germany

On 22 February 1944 aMesserschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

rammed B-17 231377 of the 327th Bombardment Squadron.On 25 May 1944 Oberfähnrich Hubert Heckmann used his

Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

to ram a P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter aircraft, fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in 1940 by a team headed ...

when his guns malfunctioned, severing the tail and rear fuselage from the American aircraft. Captain Joseph H. Bennett of the 336th Fighter Squadron

The 336th Fighter Squadron (336th FS), nicknamed ''the Rocketeers'', is a United States Air Force unit. It is assigned to the 4th Operations Group and stationed at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, North Carolina.

The 336th was constituted on 22 ...

managed to bail out to captivity, while Heckmann made an immediate belly landing near Botenheim, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

.

On 7 July 1944 Unteroffizier Willi Reschke used his Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

to ram a Consolidated B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

when his guns malfunctioned. The two falling aircraft were locked together, and it was some time before Reschke was able to free himself and bail out near Malacky

Malacky ( German: ''Malatzka'', Hungarian: ''Malacka'') is a town and municipality in western Slovakia around north of Slovakia’s capital, Bratislava. From the second half of the 10th century until 1918, it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

...

, Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

.

Late in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Luftwaffe used ramming to try to regain control of the air. The plan was to dissuade Allied bomber pilots from conducting bombing raids long enough for the Germans to create a significant number of Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed (German for "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ("Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messers ...

jet fighters to turn the tide of the air war. On 4 April 1945 Heinrich Ehrler rammed a B-24 and was killed. Only a single dedicated unit, ''Sonderkommando Elbe

''Sonderkommando'' "''Elbe''" was the name of a World War II Luftwaffe task force assigned to bring down heavy bombers by ramming them in mid-air.

Its sole mission took place on 7 April 1945, when a force of 180 Bf 109s managed to ram 15 Allie ...

'', was ever formed to the point of being operational, and flew their only mission – only a month before the end of the war in Europe – on 7 April 1945. Although some pilots succeeded in destroying bombers, Allied numbers were not significantly reduced. Perhaps the most famous example of aerial ramming carried out by ''Elbe'' that resulted in the pilot surviving ramming their plane during this mission was that of Heinrich Rosner's Bf 109 vs. B-24 44-49533 "Palace of Dallas", which was leading a formation of B-24s of the 389th Bombardment Group at the time. Rosner's plane sliced through the cockpit of "Palace of Dallas" with its wing, destroying the bomber and crippling the Bf-109, which then collided with an additional unidentified B-24. Rosner was able to successfully bail out and parachute to safety.

Projects of aircraft such as the Gotha and Zeppelin Rammjäger concepts were intended to use the ramming technique.

France

On 3 August 1944, Captain Jean Maridor of No. 91 Squadron RAF used hisSupermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft that was used by the Royal Air Force and other Allies of World War II, Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. It was the only British fighter produced conti ...

to ram a V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb ( "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Reich Aviation Ministry () name was Fieseler Fi 103 and its suggestive name was (hellhound). It was also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb or doodlebug a ...

, killing himself when the warhead detonated. Capitaine Maridor had previously damaged the V-1 with his cannon fire, and seeing it begin to dive onto a military field hospital in Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, chose to deliberately ram the bomb.

United States

On 25 October 1942 overGuadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomons by area and the second- ...

, Marine First Lieutenant Jack E. Conger of VMF-212 shot down three Mitsubishi A6M Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-capable fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 1940 to 1945. The ...

es. Pursuing a fourth Zero, Conger ran out of ammunition and decided to use his propeller to chop the tail rudder off. However, Conger misjudged the distance between his plane and the Zero and struck the plane halfway between the cockpit and the tail, tearing the entire tail off. Both Conger and the Zero pilot, Shiro Ishikawa, bailed out of their planes and were picked up by a rescue boat. For his actions, Conger was awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

.

During the battle of the Coral Sea, SBD pilot Stanley "Swede" Vejtasa was attacked by three A6M2 "Zero" fighters; he shot down two of them and cut off the wing of the third in a head-on pass with his wingtip.

On 10 May 1945 over Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

, Marine First Lieutenant Robert R. Klingman and three other pilots of VMF-312 climbed to intercept an aircraft they identified as a Kawasaki Ki-45

The Kawasaki Ki-45 ''Toryu'' (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") is a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation ; the Allied reporting name was "Nick". Originally serving as ...

''Toryu'' ("Nick") twin-engined heavy fighter flying reconnaissance at , but the "Nick" began climbing higher. Two of the FG-1D Corsairs ceased their pursuit at , but Marine Captain Kenneth Reusser and his wingman Klingman continued to , expending most of their .50 caliber ammunition to lighten their aircraft. Reusser scored hits on the "Nick's" port engine, but ran out of ammunition, and was under fire from the Japanese rear gunner. Klingman lined up for a shot at a distance of when his guns jammed due to the extreme cold. He approached the "Nick" three times to damage it with his propeller, chopping away at his opponent's rudder, rear cockpit, and right stabilizer. The ''Toryu'' spun down to where its wings came off. Despite missing five inches (13 cm) from the ends of his propeller blades, running out of fuel and having an aircraft dented and punctured by debris and bullets, Klingman safely guided his Corsair to a deadstick landing

A deadstick landing, also called a dead-stick landing or volplaning, is a type of forced landing when an aircraft loses all of its propulsive power and is forced to land. The "stick" does not refer to the flight controls, which in most aircraf ...

. He was awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Naval Service's second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is equivalent to the Army ...

.

Cold War

In the1960 U-2 incident

On 1 May 1960, a United States Lockheed U-2, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, spy plane was shot down by the Soviet Air Defence Forces while conducting photographic aerial reconnaissance inside Soviet Union, Soviet territory. Flown by American pil ...

, Soviet pilot Igor Mentyukov was scrambled with orders to ram the intruding Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed the "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-engine, high–altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since the 1950s. Designed for all- ...

, using his unarmed Sukhoi Su-9

The Sukhoi Su-9 (Air Standardization Coordinating Committee, ASCC reporting name: Fishpot) is a single-engine, all-weather, missile-armed interceptor aircraft developed by the Soviet Union.

Development

The Su-9 emerged from aerodynamic studie ...

which had been modified for higher altitude flight. In 1996, Mentyukov claimed that contact with his aircraft's slipstream downed Gary Powers

Francis Gary Powers (August 17, 1929August 1, 1977) was an American pilot who served as a United States Air Force officer and a CIA employee. Powers is best known for his involvement in the 1960 U-2 incident, when he was shot down while flyi ...

; however, Sergei Khrushchev

Sergei Nikitich Khrushchev (; 2 July 1935 – 18 June 2020) was a Soviet-born American engineer and the second son of the Cold War-era Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev with his wife Nina Petrovna Khrushcheva. He moved to the United States in 19 ...

asserted in 2000 that Mentyukov failed even to gain visual contact.

On 7 September 1965, during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, a Pakistani Lockheed F-104A Starfighter (Serial No. 56-877) from the No. 9 Squadron "Griffins" which was piloted by Flight Lieutenant Amjad Hussain Khan intercepted 6 Indian Mystere IVs which were attacking Sargodha Airbase

Pakistan Air Force Base Mushaf or more simply PAF Base Mushaf (formerly PAF Station Sargodha and PAF Base Sargodha), ) is a Pakistan Air Force airbase situated at Sargodha in Punjab, Pakistan. It is designated as a "Major Operational Base" (MOB ...

. In the ensuing dogfight

A dogfight, or dog fight, is an air combat manoeuvring, aerial battle between fighter aircraft that is conducted at close range. Modern terminology for air-to-air combat is air combat manoeuvring (ACM), which refers to tactical situations requir ...

, a Mystere flown by Squadron Leader Devaiah forced Amjad's F-104 into low-speed dogfighting (something which the F-104 performs badly in due to its poor maneuverability at reduced speeds). Though Amjad scored several hits on Devaiah's Mystere with his M-61 Vulcan and even fired a GAR-8

The AIM-9 Sidewinder is a short-range air-to-air missile. Entering service with the United States Navy in 1956 and the Air Force in 1964, the AIM-9 is one of the oldest, cheapest, and most successful air-to-air missiles. Its latest variants rema ...

at it (which missed), the Mystere was still flying. Amjad ultimately made the first jet-to-jet ramming attack against the Indian warplane. This led to both pilots losing control of their aircraft over Kot Nakka. While the Indian pilot perished with his warplane, Amjad managed to eject safely and was rescued by Pakistani

Pakistanis (, ) are the citizens and nationals of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Pakistan is the fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the second-largest Muslim population as of 2023. As much as ...

villagers watching the intense dogfight.

On 18 July 1981 Captain V.A. Kulyapin reportedly used his Su-15

The Sukhoi Su-15 (NATO reporting name: Flagon) is a twinjet supersonic interceptor aircraft developed by the Soviet Union. It entered service in 1965 and remained one of the front-line designs into the 1990s. The Su-15 was designed to replace t ...

to ram a chartered Argentine CL-44 during the 1981 Armenia mid-air collision, although Western experts believed this likely to have been a self-serving interpretation of an accidental collision.

A 1986 RAND Corporation

The RAND Corporation, doing business as RAND, is an American nonprofit global policy think tank, research institute, and public sector consulting firm. RAND engages in research and development (R&D) in several fields and industries. Since the ...

study concluded that the ramming attack was still a viable option for modern jets defending their airspace from long-range bombers if those bombers were carrying atomic weapons. The study posited that defending fighters might expend their weapons without downing the enemy bomber, and the pilots would then be faced with the final choice of ramming—almost certainly trading their lives for the many who would be killed by a successful nuclear attack.

After 1990

During the9/11

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

attacks in 2001, fighter jets were dispatched to intercept the hijacked United Airlines Flight 93

United Airlines Flight 93 was a domestic scheduled passenger flight that was hijacked by four al-Qaeda terrorists on the morning of September 11, 2001, as part of the September 11 attacks. The hijackers planned to crash the plane into a feder ...

, believed to be heading to Washington. However, there was no time for the combat jets to be armed with missiles. The pilots understood that they would be ramming the aircraft. The plane had already crashed due to an internal struggle by the time the jets arrived.

During the Hainan island incident

The Hainan Island incident was a ten-day international incident between the United States and the People's Republic of China (PRC) that resulted from a mid-air collision between a United States Navy EP-3E ARIES II SIGINT, signals intelligence a ...

, an American EP-3 SIGINT aircraft was rammed by a PLANAF

The People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force (PLANAF; zh, c=中国人民解放军海军航空兵, p = Zhōngguó Rénmín Jiěfàngjūn Hǎijūn Hángkōngbīng) is the naval aviation branch of the People's Liberation Army Navy.

History

Histor ...

J-8 interceptor.

Russo-Ukrainian War

Numerous instances ofUkrainian Ground Forces

The Ukrainian Ground Forces (SVZSU, ), also referred to as the Ukrainian army, is a land force, and one of the eight Military branch, branches of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. It was formed from Ukrainian units of the Soviet Army after Declaratio ...

drones being used for aerial ramming have been recorded; this includes an instance where a Russian DJI Mavic Pro Drone was destroyed in an aerial ramming with a Ukrainian drone on 3 October 2022, and an incident in July 2024 where an FPV drone with a stick mounted to it was used to attack and eventually destroy a ZALA 421-16E reconnaissance drone by repeatedly ramming it.

See also

*Index of aviation articles

Aviation is the design, development, production, operation, and use of aircraft, especially heavier-than-air aircraft. Articles related to aviation include:

A

Aviation accidents and incidents

– Above Mean Sea Level (AMSL)

– ADF

– Acces ...

* Mid-air collision

In aviation, a mid-air collision is an aviation accident, accident in which two or more aircraft come into unplanned contact during flight.

The potential for a mid-air collision is increased by Aviation communication, miscommunication, mistrus ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Allen Durkota; Thomas Darcy; Victor Kulikov. ''The Imperial Russian Air Service: Famous Pilots and Aircraft and World War I.'' Flying Machines Press, 1995. , 9780963711021. * * Sakaida, Henry. ''Japanese Army Air Force Aces 1937–45''. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 1997. . * Sherrod, Robert. ''History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II''. Washington, D.C.: Combat Forces Press, 1952. * Takaki, Koji and Sakaida, Henry. ''B-29 Hunters of the JAAF''. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2001. . * Tillman, Barrett. ''Corsair''. United States Naval Institute, 1979. . * * * {{cite book , last=Birdsall , first=Steve , year=1980 , title=Saga of the Superfortress: The Dramatic Story of the B-29 and the Twentieth Air Force , location=New York City , publisher=Doubleday , isbn=978-0385136686External links

Avro Project Silver Bug

Military doctrines Air-to-air combat operations and battles Vehicle-ramming attacks Aviation accidents and incidents involving deliberate crashes