Admiral Peary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

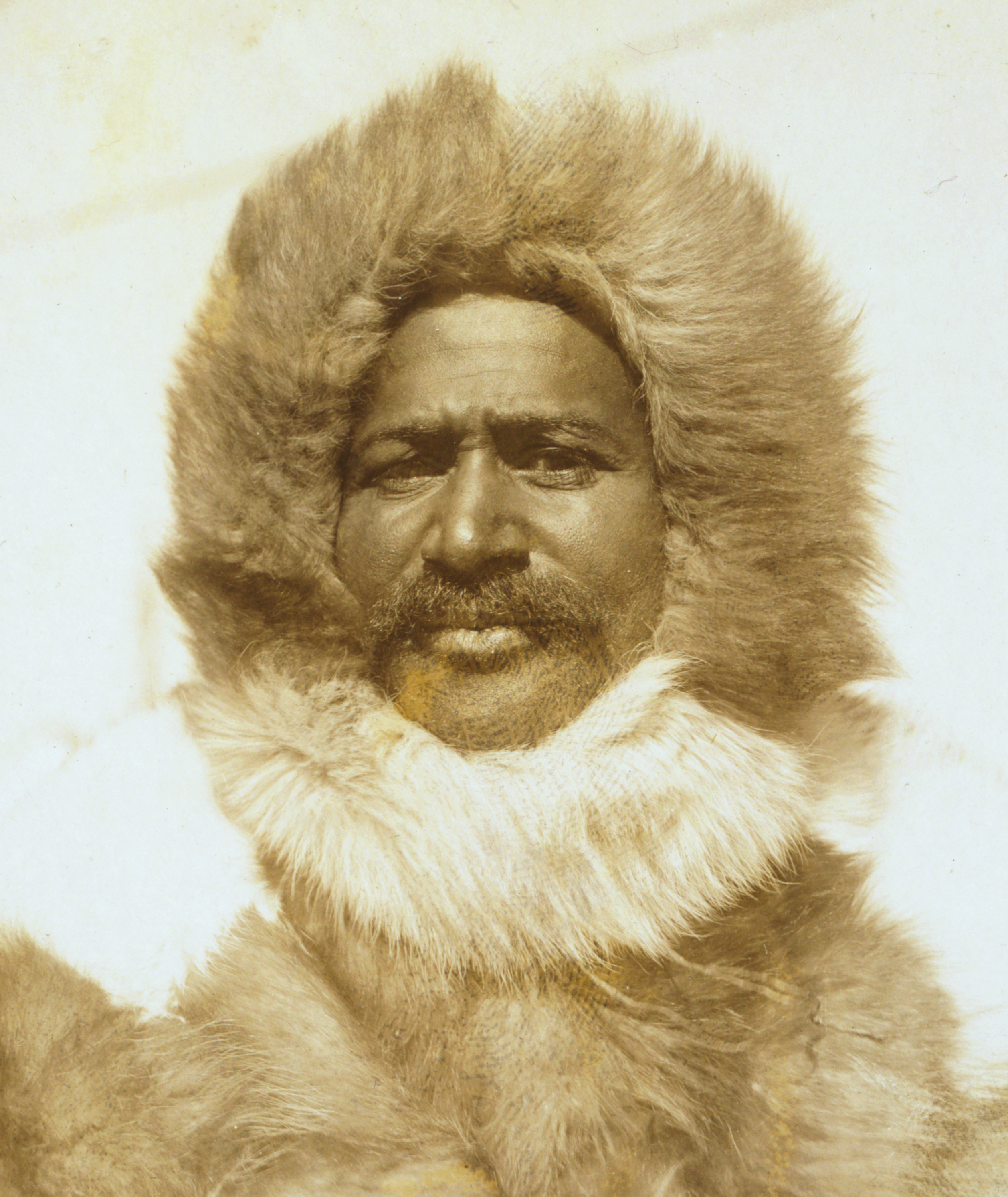

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in

Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old

Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old

On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS ''Kite''. In July, as ''Kite'' was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron

On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS ''Kite''. In July, as ''Kite'' was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron  Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied

Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied

As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of

As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of

On July 6, 1908, the ''Roosevelt'' departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the ''Roosevelt'' Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, along with

On July 6, 1908, the ''Roosevelt'' departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the ''Roosevelt'' Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, along with

On August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, a business school valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers. Diebitsch had started working at the

On August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, a business school valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers. Diebitsch had started working at the  They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including ''The Red Caboose'' (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by

They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including ''The Red Caboose'' (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by

Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, including fathering children with Aleqasina. Renée Hulan and Lyle Dick have both reported that Peary and his crew sexually exploited Inuit women on his 1908–1909 expedition. Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the

Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, including fathering children with Aleqasina. Renée Hulan and Lyle Dick have both reported that Peary and his crew sexually exploited Inuit women on his 1908–1909 expedition. Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the

Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt. Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. Peary's account has been newly criticized by

Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt. Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. Peary's account has been newly criticized by

The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than marching north. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett", where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately doubled for the five marches to Camp Jesup. The recorded speeds quadrupled during the two and a half-day return to Camp Bartlett – at which point his speed slowed drastically. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back—which would have assisted his claim of such speed—is contradicted by his companion Henson's account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (open water between those floes).

In his official report, Peary claimed to have traveled a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909, (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), to the pole, the same distance back, and in the vicinity of the pole. These distances are counted without detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance traveled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed. Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had traveled a minimum of more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity).

The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted

The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than marching north. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett", where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately doubled for the five marches to Camp Jesup. The recorded speeds quadrupled during the two and a half-day return to Camp Bartlett – at which point his speed slowed drastically. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back—which would have assisted his claim of such speed—is contradicted by his companion Henson's account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (open water between those floes).

In his official report, Peary claimed to have traveled a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909, (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), to the pole, the same distance back, and in the vicinity of the pole. These distances are counted without detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance traveled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed. Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had traveled a minimum of more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity).

The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted

The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition was finally made available for research in 1986. Historian

The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition was finally made available for research in 1986. Historian

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

who made several expeditions to the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being the discoverer of the geographic North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

in April 1909, having led the first expedition to have claimed this achievement, although it is now considered unlikely that he actually reached the Pole.

Peary was born in Cresson, Pennsylvania

Cresson is a borough in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, United States. Cresson is east of Pittsburgh. It is above in elevation. Lumber, coal, and coke yards were industries that had supported the population, which numbered 1,470 in 1910. The bo ...

, but, following his father's death at a young age, was raised in Cape Elizabeth, Maine

Cape Elizabeth is a New England town, town in Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The town is part of the Portland, Maine, Portland–South Portland, Maine, South Portland–Biddeford, Maine, Biddeford, Ma ...

. He attended Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College ( ) is a Private college, private liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. It was chartered in 1794.

The main Bowdoin campus is located near Casco Bay and the Androscoggin River. In a ...

, then joined the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

as a draftsman. He enlisted in the navy in 1881 as a civil engineer. In 1885, he was made chief of surveying for the Nicaragua Canal

Attempts to build a canal across Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean stretch back to the early colonial era. Construction of such a shipping route—using the San Juan River as an access route to Lake Nicaragua—was ...

, which was never built. He visited the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

for the first time in 1886, making an unsuccessful attempt to cross Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

by dogsled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow, a practice known as mushing. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing. Tradi ...

. In the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892

The Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892 was where Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. set out to determine if Greenland was an island, or was a peninsula of the North Pole.

History

Peary sailed from Brooklyn, New York on June 6, 1891 aboard the . Ab ...

, he was much better prepared, and by reaching Independence Fjord

Independence Fjord or Independence Sound is a large fjord or sound in the eastern part of northern Greenland. It is about long and up to wide. Its mouth, opening to the Wandel Sea of the Arctic Ocean is located at .

In the area around Indepen ...

in what is now known as Peary Land

Peary Land is a peninsula in northern Greenland, extending into the Arctic Ocean. It reaches from Victoria Fjord in the west to Independence Fjord in the south and southeast, and to the Arctic Ocean in the north, with Cape Morris Jesup, the nor ...

, he proved conclusively that Greenland was an island. He was one of the first Arctic explorers to study Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

survival techniques. During an expedition in 1894, he was the first Western explorer to reach the Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, is one of the largest known iron meteorites, classified as a medium octahedrite in chemical group IIIAB meteorites, IIIAB. In addition to many small fragments, at least eight large ...

and its fragments, which were then taken from the native Inuit population who had relied on it for creating tools. During that expedition, Peary deceived six indigenous individuals, including Minik Wallace

Minik Wallace (also called Minik or Mene) ( – October 29, 1918) was an Inughuaq (Inuk) brought as a child in 1897 from Greenland to New York City with his father and others by the explorer Robert Peary. The six Inuit were studied by staff ...

, into traveling to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year. This promise was unfulfilled and four of the six Inuit died of illnesses within a few months.

On his 1898–1902 expedition, Peary set a new "Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers, before the first successful expedition to the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete. The Arctic polar regions are much more accessible than those of the Antarctic, as ...

" record by reaching Greenland's northernmost point, Cape Morris Jesup

Cape Morris Jesup () is a headland in Peary Land, Greenland.

Geography

Cape Morris Jesup is the northernmost point of mainland Greenland, the northernmost point of any mainland, and the northernmost land point on Earth except for the small isl ...

. Peary made two more expeditions to the Arctic, in 1905–1906 and in 1908–1909. During the latter, he claimed to have reached the North Pole. Peary received several learned society

A learned society ( ; also scholarly, intellectual, or academic society) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and sciences. Membership may be open to al ...

awards during his lifetime, and, in 1911, received the Thanks of Congress

The Thanks of Congress is a series of formal resolutions passed by the United States Congress originally to extend the government's formal thanks for significant victories or impressive actions by United States, American military commanders and th ...

and was promoted to rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

. He served two terms as president of The Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904 and has served as a meeting point for ex ...

before retiring in 1911.

Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole was widely debated along with a competing claim made by Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

, but eventually won widespread acceptance. In 1989, British explorer Wally Herbert concluded Peary did not reach the pole, although he may have come within .

Early life, education, and career

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in

Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in Cresson, Pennsylvania

Cresson is a borough in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, United States. Cresson is east of Pittsburgh. It is above in elevation. Lumber, coal, and coke yards were industries that had supported the population, which numbered 1,470 in 1910. The bo ...

, to Charles N. and Mary P. Peary. After his father died in 1859, Peary and his mother moved to Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

. Peary attended Portland High School (Maine)

Portland High School is a public high school established in 1821 in Portland, Maine, United States, which educates grades 9–12. The school is part of the Portland Public Schools district, and is one of three high schools in that district, ...

where he graduated in 1873. Peary made his way to Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College ( ) is a Private college, private liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. It was chartered in 1794.

The main Bowdoin campus is located near Casco Bay and the Androscoggin River. In a ...

, some to the north, where he was a member of the Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest Fraternities and sororities, fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active Colony (fraternity or sorority), colonies across No ...

fraternity and the Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

honor society

In the United States, an honor society is an organization that recognizes individuals who rank above a set standard in various domains such as academics, leadership, and other personal achievements, not all of which are based on ranking systems. ...

. He was also part of the rowing team. He graduated in 1877 with a civil engineering

Civil engineering is a regulation and licensure in engineering, professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads ...

degree.Mills 2003, p. 510.

From 1878 to 1879, Peary lived in Fryeburg, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. During that time, he made a profile survey from the top of Fryeburg's Jockey Cap Rock. The 360-degree survey names the larger hills and mountains visible from the summit. After Peary's death, his boyhood friend, Alfred E. Burton, suggested that the profile survey be made into a monument. It was cast in bronze and set atop a granite cylinder and erected to his memory by the Peary family in 1938.

After college, Peary worked as a draftsman making technical drawings at the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

office in Washington, D.C. He joined the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

and on October 26, 1881, was commissioned in the Civil Engineer Corps

The Civil Engineer Corps (CEC) is a staff corps of the United States Navy. CEC officers are professional engineers and architects, acquisitions specialists, and Seabee Combat Warfare Officers who qualify within Seabee units. They are responsib ...

, with the relative rank of lieutenant. From 1884 to 1885, he was an assistant engineer on the surveys for the Nicaragua Canal

Attempts to build a canal across Nicaragua to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean stretch back to the early colonial era. Construction of such a shipping route—using the San Juan River as an access route to Lake Nicaragua—was ...

and later became the engineer in charge. As reflected in a diary entry he made in 1885, during his time in the Navy, he resolved to be the first man to reach the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

.

In April 1886, he wrote a paper for the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

proposing two methods for crossing Greenland's ice cap. One was to start from the west coast and trek about to the east coast. The second, more difficult path, was to start from Whale Sound

The Whale Sound () is a sound in the Avannaata municipality, NW Greenland.GoogleEarth

Geography

It is a broad channel that runs roughly from east to west between the mouth of the Inglefield Fjord and Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Sa ...

at the top of the known portion of Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; ; ; ), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is sometimes considered a s ...

and travel north to determine whether Greenland was an island or if it extended all the way across the Arctic. Peary was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander on January 5, 1901, and to commander on April 6, 1902.

Initial Arctic expeditions

Peary made his first expedition to theArctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

in 1886, intending to cross Greenland by dog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow, a practice known as mushing. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for Sled dog racing, dog sl ...

, taking the first of his own suggested paths. He was given six months' leave from the Navy, and he received $500 from his mother to book passage north and buy supplies. He sailed on a whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

to Greenland, arriving in Godhavn

Qeqertarsuaq (, historically known as Godhavn) is a port and town in Qeqertalik municipality, located on the south coast of Disko Island on the west coast of Greenland. Founded in 1773, the town is now home to a campus of the University of Cope ...

on June 6, 1886. Peary wanted to make a solo trek, but Christian Maigaard, a young Danish official, convinced him he would die if he went out alone. Maigaard and Peary set off together and traveled nearly due east before turning back because they were short on food. This was the second-farthest penetration of Greenland's ice sheet at the time. Peary returned home knowing more of what was required for long-distance ice trekking.Mills 2003, p. 511.

Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old

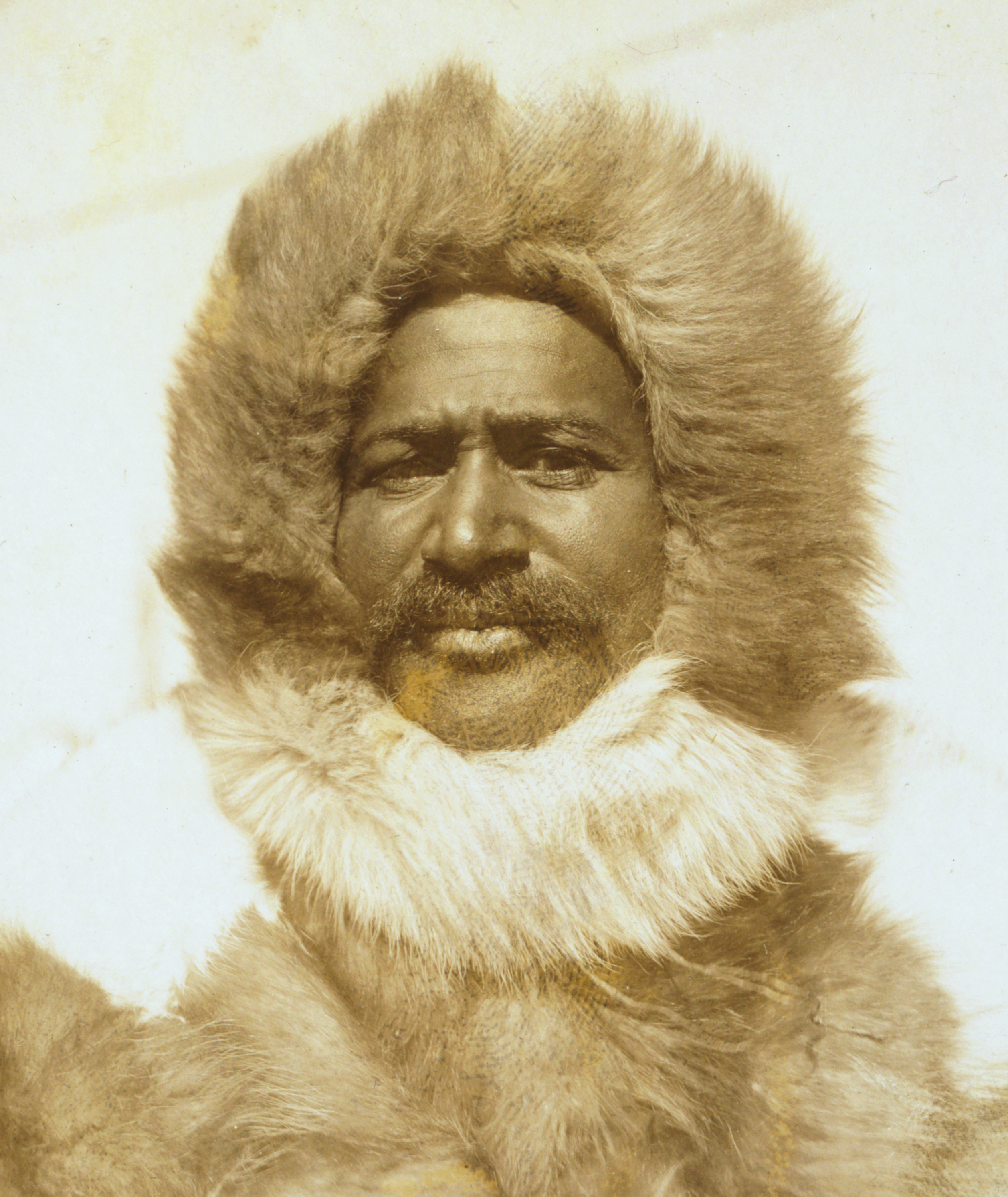

Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old Matthew Henson

Matthew Alexander Henson (August 8, 1866March 9, 1955) was an African American explorer who accompanied Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic over a period of nearly 23 years. They spent a total of 18 years on expeditions together.

, a black man working as a sales clerk. Learning that Henson had six years of seagoing experience as a cabin boy

A cabin boy or ship's boy is a boy or young man who waits on the officers and passengers of a ship, especially running errands for the captain. The modern merchant navy successor to the cabin boy is the steward's assistant.

Duties

Cabin boys ...

, Peary immediately hired him as a personal valet

A valet or varlet is a male servant who serves as personal attendant to his employer. In the Middle Ages and Ancien Régime, ''valet de chambre'' was a role for junior courtiers and specialists such as artists in a royal court, but the term "va ...

.Nuttall 2012, p. 855–856.

On assignment in the jungles of Nicaragua, Peary told Henson of his dream of Arctic exploration. Henson accompanied Peary on every one of his subsequent Arctic expeditions, becoming his field assistant and "first man", a critical member of his team.

Second Greenland expedition

In thePeary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892

The Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892 was where Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. set out to determine if Greenland was an island, or was a peninsula of the North Pole.

History

Peary sailed from Brooklyn, New York on June 6, 1891 aboard the . Ab ...

, Peary took the second, more difficult route that he laid out in 1886: traveling farther north to find out whether Greenland was a larger landmass extending to the North Pole. He was financed by several groups, including the American Geographic Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

, the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences (now the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natur ...

), and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences

The Brooklyn Museum is an art museum in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. At , the museum is New York City's second largest and contains an art collection with around 500,000 objects. Located near the Prospect Heights, Crown Heights, Fla ...

. Members of this expedition included Peary's aide Henson, Frederick A. Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

, who served as the group's surgeon; the expedition's ethnologist, Norwegian skier Eivind Astrup

Eivind Astrup (; 17 September 1871 – 27 December 1895) was a Norwegian explorer and writer. Astrup participated in Robert Peary's Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–92, expedition to Greenland in 1891–92 and mapped northern Greenland. ...

; bird expert and marksman Langdon Gibson, and John M. Verhoeff, who was a weatherman and mineralogist. Peary also took his wife, Josephine, along as dietitian, though she had no formal training. Newspaper reports criticized Peary for bringing his wife.

On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS ''Kite''. In July, as ''Kite'' was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron

On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS ''Kite''. In July, as ''Kite'' was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron tiller

A tiller or till is a lever used to steer a vehicle. The mechanism is primarily used in watercraft, where it is attached to an outboard motor, rudder post, rudder post or stock to provide leverage in the form of torque for the helmsman to turn ...

suddenly spun around and broke Peary's lower right leg; both bones snapped between the knee and ankle. Peary was unloaded with the rest of the supplies at a camp they called Red Cliff, at the mouth of MacCormick Fjord at the north west end of Inglefield Gulf. A dwelling was built for his recuperation during the next six months. Josephine Peary stayed with Peary. Gibson, Cook, Verhoeff, and Astrup hunted game by boat and became familiar with the area and the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

.

Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied

Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

survival techniques; he built igloo

An igloo (Inuit languages: , Inuktitut syllabics (plural: )), also known as a snow house or snow hut, is a type of shelter built of suitable snow.

Although igloos are often associated with all Inuit, they were traditionally used only by the ...

s during the expedition and dressed in practical furs in the native fashion. By wearing furs to preserve body heat and building igloos, he was able to dispense with the extra weight of tents and sleeping bags when on the march. Peary also relied on the Inuit as hunters and dog-drivers on his expeditions. He pioneered the system of using support teams and establishing supply caches for Arctic travel, which he called the "Peary system". The Inuit were curious about the Americans and came to visit Red Cliff. Josephine was bothered by the Inuit body odor from not bathing, their flea infestations, and their food. She studied the people and kept a journal of her experiences. In September 1891, Peary's men and dog sled teams pushed inland onto the ice sheet to lay caches of supplies. They did not go farther than from Red Cliff.

In 1891, Peary shattered his right leg in a shipyard accident but it healed by February 1892. By April 1892, he made some short trips with Josephine and an Inuk dog sled driver to native villages to purchase supplies. On May 3, 1892, Peary finally set out on the intended trek with Henson, Gibson, Cook, and Astrup. After , Peary continued on with Astrup. They found the high view from Navy Cliff, saw Independence Fjord

Independence Fjord or Independence Sound is a large fjord or sound in the eastern part of northern Greenland. It is about long and up to wide. Its mouth, opening to the Wandel Sea of the Arctic Ocean is located at .

In the area around Indepen ...

, and concluded that Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

was an island, and not connected to some yet unknown landmass further north in the Arctic. They trekked back to Red Cliff and arrived on August 6, having traveled a total of .

In 1896, Peary, a Master Mason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, received his degrees in Kane Lodge No. 454, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

1898–1902 expeditions

As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of

As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

. He claimed that this sighting of Axel Heiberg Island

Axel Heiberg Island (, ) is an uninhabited island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. Located in the Arctic Ocean, it is the 32nd largest island in the world and Canada's seventh largest island. According to Statistics Canada, it ha ...

was prior to its discovery by Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup

Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup (31 October 1854 – 26 November 1930) was a Norwegian sailor and Arctic explorer.

Early and personal life

He was born in Bindal Municipality as a son of farmer Ulrik Frederik Suhm Sverdrup (1833–1914) and his w ...

's expedition around the same time. This contention has been universally rejected by exploration societies and historians. However, the American Geographical Society and the Royal Geographical Society of London honored Peary for tenacity, mapping of previously uncharted areas, and his discovery in 1900 of Cape Morris Jesup

Cape Morris Jesup () is a headland in Peary Land, Greenland.

Geography

Cape Morris Jesup is the northernmost point of mainland Greenland, the northernmost point of any mainland, and the northernmost land point on Earth except for the small isl ...

at the north tip of Greenland. Peary also achieved a "farthest north" for the western hemisphere in 1902 north of Canada's Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

. Peary was promoted to lieutenant commander in the Navy in 1901 and to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

in 1902.

1905–1906 expedition

Peary's next expedition was supported by fundraising through thePeary Arctic Club

The Peary Arctic Club was an American-based Club (organization), club with the goal of promoting the Arctic expeditions of Robert Peary (1856–1920).

This association of influential persons was able to overcome the opposition of the U.S. Nav ...

, with gifts of $50,000 from George Crocker, the youngest son of banker Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

, and $25,000 from Morris K. Jesup, to buy Peary a new ship. The navigated through the ice between Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

, establishing an American hemisphere "farthest north by ship". The 1906 "Peary System" dogsled drive for the pole across the rough sea ice of the Arctic Ocean started from the north tip of Ellesmere at 83° north latitude. The parties made well under a day until they became separated by a storm.

As a result, Peary was without a companion sufficiently trained in navigation to verify his account from that point northward. With insufficient food, and uncertainty whether he could negotiate the ice between himself and land, he made the best possible dash and barely escaped with his life from the melting ice. On April 20, he was no farther north than 86°30' latitude. This latitude was never published by Peary. It is in a typescript of his April 1906 diary, discovered by Wally Herbert in his assessment commissioned by the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

. The typescript suddenly stopped there, one day before Peary's April 21 purported "farthest". The original of the April 1906 record is the only missing diary of Peary's exploration career. He claimed the next day to have achieved a Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers, before the first successful expedition to the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete. The Arctic polar regions are much more accessible than those of the Antarctic, as ...

world record at 87°06' and returned to 86°30' without camping. This implied a trip of at least between sleeping, even assuming direct travel with no detours.

After returning to ''Roosevelt'' in May, Peary began weeks of difficult travel in June heading west along the shore of Ellesmere. He discovered Cape Colgate, from whose summit he claimed in his 1907 book that he had seen a previously undiscovered far-north " Crocker Land" to the northwest on June 24, 1906. A later review of his diary for this time and place found that he had written, "No land visible." On December 15, 1906, the National Geographic Society of the United States, certified Peary's 1905–1906 expedition and "Farthest" with its highest honor, the Hubbard Medal

The Hubbard Medal is awarded by the National Geographic Society for distinction in exploration, discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learnin ...

. No major professional geographical society followed suit. In 1914, Donald Baxter MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an Americans, American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, air ...

and Fitzhugh Green, Sr.'s expedition found that Crocker Land did not exist.

Reaching the North Pole

On July 6, 1908, the ''Roosevelt'' departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the ''Roosevelt'' Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, along with

On July 6, 1908, the ''Roosevelt'' departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the ''Roosevelt'' Robert Bartlett, surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, along with Ross Gilmore Marvin

Ross Gilmore Marvin (January 28, 1880 – after December 8, 1908; reported as April 10, 1909) was an American explorer who took part in Robert Peary's 1905–1906 and 1908–1909 expeditions to the Arctic. It was initially believed that Marvin dr ...

, Donald Baxter MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an Americans, American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, air ...

, George Borup, and Matthew Henson

Matthew Alexander Henson (August 8, 1866March 9, 1955) was an African American explorer who accompanied Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic over a period of nearly 23 years. They spent a total of 18 years on expeditions together.

. After recruiting several Inuit and their families at Cape York (Greenland)

Cape York (, ) is a cape on the northwestern coast of Greenland, in northern Baffin Bay.

Geography

It is a pronounced projection. It delimits the northwestern end of Melville Bay, with the other end commonly defined as Wilcox Head, the weste ...

, the expedition wintered near Cape Sheridan

Cape Sheridan is on the northeastern coast of Ellesmere Island, Canada situated on the Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean, on the mouth of Sheridan River, west bank. It is one of the closest points of land to the geographic North Pole, approxima ...

on Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

. The expedition used the "Peary system" for the sledge journey, with Bartlett and the Inuit, Poodloonah, "Harrigan," and Ooqueah, composing the pioneer division. Borup, with three Inuit, Keshunghaw, Seegloo, and Karko, composed the advance supporting party. On February 15, Bartlett's pioneer division departed the ''Roosevelt'' for Cape Columbia

Cape Columbia is the northernmost point of land of Canada, located on Ellesmere Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. It marks the westernmost coastal point of Lincoln Sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is the world's northernmost point of l ...

, followed by 5 advance divisions. Peary, with the two Inuit, Arco and Kudlooktoo, departed on February 22, bringing to the total effort 7 expedition members, 19 Inuit, 140 dogs, and 28 sledges. On February 28, Bartlett, with three Inuit, Ooqueah, Pooadloonah, and Harrigan, accompanied by Borup, with three Inuit, Karko, Seegloo, and Keshungwah, headed North.

On March 14, the first supporting party, composed of Dr. Goodsell and the two Inuit, Arco and Wesharkoupsi, turned back towards the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 84°29'. On March 20, Borup's third supporting party, with three Inuit, started back to the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 85°23'. On March 26, Marvin, with Kudlooktoo and Harrigan, headed back to the ship, from a latitude estimated by Marvin as 86°38'. Marvin died on this return trip south. On 1 April, Bartlett's party started their return to the ship, after Bartlett estimated a latitude of 87°46'49". Peary, with two Inuit, Egingwah and Seeglo, and Henson, with two Inuit, Ootah and Ooqueah, using 5 sledges and 40 dogs, planned 5 marches over the estimated 130 nautical mile

A nautical mile is a unit of length used in air, marine, and space navigation, and for the definition of territorial waters. Historically, it was defined as the meridian arc length corresponding to one minute ( of a degree) of latitude at t ...

s to the pole. On 2 April, Peary led the way north.

On the final stage of the journey toward the North Pole, Peary told Bartlett to stay behind. He continued with five others: Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah. No one except Henson, who had served on the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892

The Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892 was where Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. set out to determine if Greenland was an island, or was a peninsula of the North Pole.

History

Peary sailed from Brooklyn, New York on June 6, 1891 aboard the . Ab ...

, had experience of naval-type observations. On April 6, 1909, Peary established Camp Jesup within of the pole, according to his own readings. Peary estimated the latitude as 89°57', after making an observation at approximate local noon using the Columbia meridian. Peary used a sextant, with a mercury trough and glass roof for an artificial horizon, to make measurements of the Sun. Peary claims, "I had now taken in all thirteen single, or six and one-half double, altitudes of the sun, at two different stations, in three different directions, at four different times." Peary states some of these observations were "beyond the Pole," and "...at some moment during these marches and counter-marches, I had passed over or very near the point where north and south and east and west blend into one." Henson scouted ahead to what was thought to be the North Pole site; he returned with the greeting, "I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world," much to Peary's chagrin.

On April 7, 1909, Peary's group started their return journey, reaching Cape Columbia on April 23, and the ''Roosevelt'' on April 26. MacMillan and the doctor's party had reached the ship earlier, on March 21, Borup's party on April 11, Marvin's Inuit on April 17, and Bartlett's party on April 24. On July 18, the ''Roosevelt'' departed for home.

Upon returning, Peary learned that Dr. Frederick A. Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician and ethnographer, who is most known for allegedly being the first to reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. A competing claim was made a year l ...

, a surgeon and ethnographer on the Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892

The Peary expedition to Greenland of 1891–1892 was where Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. set out to determine if Greenland was an island, or was a peninsula of the North Pole.

History

Peary sailed from Brooklyn, New York on June 6, 1891 aboard the . Ab ...

, claimed to have reached the North pole in 1908. Despite remaining doubts, a committee of the National Geographic Society, as well as the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, credited Peary with reaching the North Pole.

A reassessment of Peary's notebook in 1988 by polar explorer Wally Herbert found it "lacking in essential data", thus renewing doubts about Peary's discovery.

Later life and death

Peary was promoted to the rank of captain in the Navy in October 1910. By his lobbying, Peary headed off a move among some U.S. Congressmen to have his claim to the pole evaluated by other explorers. Eventually recognized by Congress for "reaching" the pole, Peary was given theThanks of Congress

The Thanks of Congress is a series of formal resolutions passed by the United States Congress originally to extend the government's formal thanks for significant victories or impressive actions by United States, American military commanders and th ...

by a special act in March 1911. By the same Act of Congress, Peary was promoted to the rank of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

in the Navy Civil Engineer Corps, retroactive to April 6, 1909. He retired from the Navy the same day, to Eagle Island on the coast of Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, in the town of Harpswell. His home there has been designated a Maine State Historic Site.

After retiring, Peary received many honors from scientific societies for his Arctic explorations and discoveries. He served twice as president of The Explorers Club

The Explorers Club is an American-based international multidisciplinary professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. The club was founded in New York City in 1904 and has served as a meeting point for ex ...

, from 1909 to 1911, and from 1913 to 1916.

In early 1916, Peary became chairman of the National Aerial Coast Patrol Commission, a private organization created by the Aero Club of America

The Aero Club of America was a social club formed in 1905 by Charles Jasper Glidden and Augustus Post, among others, to promote aviation in America. It was the parent organization of numerous state chapters, the first being the Aero Club of New E ...

. It advocated the use of aircraft to detect warships and submarines off the U.S. coast. Peary used his celebrity to promote the use of military and naval aviation, which led directly to the formation of United States Navy Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2004, is the Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called reservists, are categorized as being in either the S ...

aerial coastal patrol units during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. After the war, Peary proposed a system of eight airmail routes, which became the genesis of the U.S. Postal Service's airmail system.

In 1914, Peary bought the house at 1831 Wyoming Avenue NW in the Adams Morgan

Adams Morgan (abbreviated as AdMo) is a Neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood in Washington, D.C., located in the city’s Northwest (Washington, D.C.), Northwest quadrant. Adams Morgan is noted as a historic hub for Counterculture of ...

neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, where he lived until his death on February 20, 1920. He began renovating the house in 1920, shortly before his death, after which the renovation was taken over by Josephine. She sold the house in 1927, receiving a $12,000 promissory note.

He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

. Matthew Henson was honored by being re-interred nearby on April 6, 1988.

Marriage and family

On August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, a business school valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers. Diebitsch had started working at the

On August 11, 1888, Peary married Josephine Diebitsch, a business school valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers. Diebitsch had started working at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

when she was 19 or 20 years old, replacing her father after he became ill and filling his position as a linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

. In 1886, she resigned from the Smithsonian upon becoming engaged to Peary.

The newlyweds honeymooned in Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, sometimes referred to by its initials A.C., is a Jersey Shore seaside resort city (New Jersey), city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, Atlantic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Atlantic City comprises the second half of ...

, then moved to Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, where Peary was assigned. Peary's mother accompanied them on their honeymoon, and she moved into their Philadelphia apartment, which caused friction between the two women. Josephine told Peary that his mother should return to live in Maine.

They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including ''The Red Caboose'' (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by

They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including ''The Red Caboose'' (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by William Morrow and Company

William Morrow and Company is an American publishing company founded by William Morrow in 1926. The company was acquired by Scott Foresman in 1967, sold to Hearst Corporation in 1981, and sold to News Corporation (now News Corp) in 1999. The ...

. As an explorer, Peary was frequently gone for years at a time. In their first 23 years of marriage, he spent only three with his wife and family.

Peary and his aide, Henson, both had relationships with Inuit women outside of marriage and fathered children with them. Peary appears to have started a relationship with Aleqasina (''Alakahsingwah'') when she was about 14 years old. They had at least two children, including a son called Kaala, Karree, or Kali. French explorer and ethnologist Jean Malaurie was the first to report on Peary's descendants after spending a year in Greenland in 1951–52.

S. Allen Counter, a Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

neuroscience professor interested in Henson's role in the Arctic expeditions, went to Greenland in 1986. He found Peary's son Kali and Henson's son Anaukaq, then octogenarians, and some of their descendants. Counter arranged to bring the men and their families to the United States to meet their American relatives and see their fathers' gravesites. In 1991, Counter wrote about the episode in his book, ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo'' (1991). He also gained national recognition of Henson's role in the expeditions. A documentary by the same name was also released. Wally Herbert also noted the relationship and children in his book ''The Noose of Laurels'', published in 1989.

Treatment of the Inuit

Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, including fathering children with Aleqasina. Renée Hulan and Lyle Dick have both reported that Peary and his crew sexually exploited Inuit women on his 1908–1909 expedition. Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the

Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, including fathering children with Aleqasina. Renée Hulan and Lyle Dick have both reported that Peary and his crew sexually exploited Inuit women on his 1908–1909 expedition. Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of Inughuit Greenlandic Inuit to the United States along with the Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, is one of the largest known iron meteorites, classified as a medium octahedrite in chemical group IIIAB meteorites, IIIAB. In addition to many small fragments, at least eight large ...

. The meteorite was of significant local economic importance: Although the Greenlanders had been obtaining the iron they needed from whalers, the Cape York meteorite was the only source of iron for tools. Peary sold it for $40,000 in 1897.

Working at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

, anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

had requested that Peary bring back an Inuk for study. During his expedition to retrieve the meteorite, Peary convinced six people, including a man named Qisuk and his child Minik, to travel to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year. Peary left the people at the museum when he returned with the meteorite in 1897, where they were kept in damp, humid conditions unlike their homeland. Within a few months, four died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

; their remains were dissected and the bones of Qisuk were put on display after Minik was shown a fake burial.

Speaking as a teenager to the ''San Francisco Examiner

The ''San Francisco Examiner'' is a newspaper distributed in and around San Francisco, California, and has been published since 1863.

Once self-dubbed the "Monarch of the Dailies" by then-owner William Randolph Hearst and the flagship of the He ...

'' about Peary, Minik said:

Peary eventually helped Minik travel home in 1909, though it is speculated that this was to avoid any bad press surrounding his anticipated celebratory return after reaching the North Pole. In 1986, Kenn Harper

Kenn Harper (aka ''Ilisaijikutaaq'', tall teacher) is a Canadian writer, historian and former businessman. He is the author of ''Give Me My Father's Body'', an account of Greenland Inuk Minik Wallace, had a regular column on Arctic history in ''N ...

wrote a book about Minik, entitled ''Give Me My Father's Body''. Convinced that the remains of Qisuk and the three adult Inuit should be returned to Greenland, he tried to persuade the Museum of Natural History to do this, as well as working through the "red tape" of the US and Canadian governments. In 1993, Harper succeeded in having the Inuit remains returned. In Qaanaaq

Qaanaaq (), formerly known as New Thule, is the main town in the northern part of the Avannaata municipality in northwestern Greenland. The town has a population of 646 as of 2020. The population was forcibly relocated from its former, traditiona ...

, he witnessed the Inuit funeral ceremony for the remains of Qisuk and the three tribesmen haman Atangana (ca. 1840–1898) with her husband, renowned hunter Nuktaq (ca. 1848–1898), their adoptive daughter Aviaq (ca. 1885–1898)that had been taken to New York.

Peary had employed the Inughuit in his expeditions for more than a decade, paying them in firearms, ammunition and other Western goods on which they had come to rely, and leaving them in a dire situation in 1909. The demands of the American expeditions had also resulted in the caribou of North Greenland being hunted to near extinction.

Controversy surrounding North Pole claim

Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt. Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. Peary's account has been newly criticized by

Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt. Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. Peary's account has been newly criticized by Pierre Berton

Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton, CC, O.Ont. (July 12, 1920 – November 30, 2004) was a Canadian historian, writer, journalist and broadcaster. Berton wrote 50 best-selling books, mainly about Canadiana, Canadian history and popular cultur ...

(2001) and Bruce Henderson (2005).

Lack of independent validation

Peary did not submit his evidence for review to neutral national or international parties or to other explorers. Peary's claim was certified by theNational Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

(NGS) in 1909 after a cursory examination of Peary's records, as NGS was a major sponsor of his expedition. This was a few weeks before Cook's Pole claim was rejected by a Danish panel of explorers and navigational experts.

The National Geographic Society limited access to Peary's records. At the time, his proofs were not made available for scrutiny by other professionals, as had been done by the Danish panel. Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor persuaded the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

not to get involved. The Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

(RGS) of London gave Peary a one-off medal (created by sculptor Kathleen Scott, later widow of Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

), in 1910, despite internal council splits which only became known in the 1970s. The RGS based their decision on the belief that the NGS had performed a serious scrutiny of the "proofs", which was not the case. Neither the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are United States, Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows f ...

nor any of the geographical societies of semi-Arctic Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

has recognized Peary's North Pole claim.

Criticisms

Omissions in navigational documentation

The party that accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey did not include anyone trained in navigation who could either confirm or contradict Peary's own navigational work. This was further exacerbated by Peary's failure to produce records of observed data for steering, for the direction (" variation") of the compass, for his longitudinal position at any time, or for zeroing-in on the pole either latitudinally or transversely beyond Bartlett Camp.Inconsistent speeds

The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than marching north. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett", where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately doubled for the five marches to Camp Jesup. The recorded speeds quadrupled during the two and a half-day return to Camp Bartlett – at which point his speed slowed drastically. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back—which would have assisted his claim of such speed—is contradicted by his companion Henson's account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (open water between those floes).

In his official report, Peary claimed to have traveled a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909, (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), to the pole, the same distance back, and in the vicinity of the pole. These distances are counted without detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance traveled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed. Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had traveled a minimum of more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity).

The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted

The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than marching north. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett", where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately doubled for the five marches to Camp Jesup. The recorded speeds quadrupled during the two and a half-day return to Camp Bartlett – at which point his speed slowed drastically. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back—which would have assisted his claim of such speed—is contradicted by his companion Henson's account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (open water between those floes).

In his official report, Peary claimed to have traveled a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909, (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), to the pole, the same distance back, and in the vicinity of the pole. These distances are counted without detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance traveled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed. Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had traveled a minimum of more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity).

The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

to take extensive precautions in navigation during Amundsen's South Pole expedition

The first ever expedition to reach the Geographic South Pole was led by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. He and four other crew members made it to the geographical south pole on 14 December 1911, which would prove to be five weeks ahea ...

so as to leave no room for doubt concerning his 1911 attainment of the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is the point in the Southern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True South Pole to distinguish ...

, which—like Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

's a month later in 1912—was supported by the sextant, theodolite

A theodolite () is a precision optical instrument for measuring angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. The traditional use has been for land surveying, but it is also used extensively for building and ...

, and compass observations of several other navigators.

Review of Peary's diary

The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition was finally made available for research in 1986. Historian

The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition was finally made available for research in 1986. Historian Larry Schweikart

Larry Earl Schweikart (; born April 21, 1951) is an American historian and retired professor of history at the University of Dayton. During the 1980s and 1990s, he authored numerous scholarly publications. In recent years, he has authored popula ...

examined it, finding that: the writing was consistent throughout (giving no evidence of post-expedition alteration), there were consistent pemmican

Pemmican () (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigeno ...

and other stains on all pages, and all evidence was consistent with a conclusion that Peary's observations were made on the spot he claimed. Schweikart compared the reports and experiences of Japanese explorer Naomi Uemura, who reached the North Pole alone in 1978, to those of Peary and found they were consistent. However, Peary made no entries in the diary on the crucial days of April 6 and 7, 1909, and his famous words "The Pole at Last!", allegedly written in his diary at the pole, were written on loose slips of paper that were inserted into the diary.

1984 and 1989 National Geographic Society studies

In 1984, theNational Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

(NGS), a major sponsor of Peary's expeditions, commissioned Wally Herbert, an Arctic explorer himself, to write an assessment of Peary's original 1909 diary and astronomical observations. As Herbert researched the material, he came to believe that Peary falsified his records and concluded that he did not reach the North Pole. His book, ''The Noose of Laurels'', caused a furor when it was published in 1989. If Peary did not reach the pole in 1909, Herbert would claim the record of being the first to reach the pole on foot.

In 1989, the NGS also conducted a two-dimensional photogrammetric analysis of the shadows in photographs and a review of ocean depth measures taken by Peary; its staff concluded that he was no more than away from the pole. Peary's original camera, a 1908 #4 Folding Pocket Kodak

The Eastman Kodak Company, referred to simply as Kodak (), is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in film photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorporated i ...

, did not survive. As such cameras were made with at least six different lenses from various manufacturers, the focal length of the lens, and hence the shadow analysis based on it, must be considered uncertain at best. The NGS has never released Peary's photos for an independent analysis. Specialists questioned the conclusions of the NGS. The NGS commissioned the Foundation for the Promotion of the Art of Navigation to resolve the issue, which concluded that Peary had indeed reached the North Pole.

Review of depth soundings

Supporters of Peary and Henson assert that the depth soundings they made on the outward journey have been matched by recent surveys, and so their claim of having reached the Pole is confirmed. Since only the first few of the Peary party's soundings, taken nearest the shore, touched bottom; experts have said their usefulness is limited to showing that he was above deep water. Peary's expedition possessed 4,000 fathoms of sounding line, but he took only 2,000 with him over an ocean already established as being deeper in many regions. Peary stated in 1909 Congressional hearings about the expedition that he made no longitudinal observations during his trip, only latitude observations, yet he maintained he stayed on the "Columbia meridian" all along, and that his soundings were made on this meridian. The pack ice was moving all the time, so he had no way of knowing where he was without longitudinal observations.Re-creation of expedition in 2005

In 2005, British explorer Tom Avery and four companions re-created the outward portion of Peary's journey using replica wooden sleds andCanadian Eskimo Dog

The Canadian Eskimo Dog or Canadian Inuit Dog is a breed of working dog from the Arctic. Other names include ''qimmiq''Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College is named for Peary and fellow Arctic explorer

Peary-Cook Controversy Collection

at Dartmouth College Library

Robert Peary papers

at Dartmouth College Library

Arthur Malcolm Dodge Photographs and Article on 1896 Peary Expedition

at Dartmouth College Library

George Putnam Diary and Photo Album from the 1896 Peary Greenland Expedition

at Dartmouth College Library

Personal Diary of J.M. Wiseman fireman of S.S. Roosevelt

at Dartmouth College Library

Photo at NOAA Photo Library "Rear Admiral Robert E. Peary, who during his quest for the Pole conducted tidal observations in the Arctic Ocean"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Peary, Robert 1856 births 1920 deaths American Freemasons American polar explorers Bowdoin College alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Discovery and invention controversies American explorers of the Arctic Fellows of the Explorers Club 20th-century American explorers Grand Officers of the Legion of Honour People from Adams Morgan People from Cambria County, Pennsylvania People from Harpswell, Maine People from Portland, Maine Portland High School (Maine) alumni Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal United States Coast and Geodetic Survey personnel United States Navy rear admirals (lower half) American Geographical Society Military personnel from Pennsylvania

Donald Baxter MacMillan

Donald Baxter MacMillan (November 10, 1874 – September 7, 1970) was an Americans, American explorer, sailor, researcher and lecturer who made over 30 expeditions to the Arctic during his 46-year career.

He pioneered the use of radios, air ...

. Robert E. Peary Middle School in Gardena, CA, and Robert E. Peary High School in Rockvile, MD, were named after him. In 1986, the United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or simply the Postal Service, is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the federal governmen ...

issued a 22-cent postage stamp in honor of Peary and Henson;

Peary Land

Peary Land is a peninsula in northern Greenland, extending into the Arctic Ocean. It reaches from Victoria Fjord in the west to Independence Fjord in the south and southeast, and to the Arctic Ocean in the north, with Cape Morris Jesup, the nor ...

, Peary Glacier, Peary Nunatak and Cape Peary in Greenland, Peary Bay and Peary Channel in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, as well as Mount Peary in Antarctica, are named in his honor. The lunar crater Peary, located at the Moon's north pole, is also named after him.

Camp Peary

Camp Peary is a U.S. military reservation in York County near Williamsburg, Virginia, which hosts a covert CIA training facility known as "The Farm". Officially referred to as an Armed Forces Experimental Training Activity (AFETA) under the ...

in York County, Virginia is named for Admiral Peary. Originally established as a Navy Seabee

United States Naval Construction Battalions, better known as the Navy Seabees, form the U.S. Naval Construction Forces (NCF). The Seabee nickname is a heterograph of the initial letters "CB" from the words "Construction Battalion". Dependi ...

training center during World War II, it was repurposed in the 1950s as a Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

training facility. It is commonly called "The Farm".

Admiral Peary Vocational Technical School, located in a neighboring community very close to his birthplace of Cresson, PA, was named for him and was opened in 1972. Today the school educates over 600 students each year in numerous technical education disciplines.

A section of U.S. Route 22 in Cambria County, Pennsylvania