Aconitum Saxatile on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Aconitum'' (), also known as aconite, monkshood, wolfsbane, leopard's bane, devil's helmet, or blue rocket, is a

The name ''aconitum'' comes from the Greek word , which may derive from the Greek ''akon'' for dart or

The name ''aconitum'' comes from the Greek word , which may derive from the Greek ''akon'' for dart or

The tall, erect stem is crowned by

The tall, erect stem is crowned by

The species typically utilized by gardeners fare well in well-drained evenly moist "humus-rich" garden soils like many in the related

The species typically utilized by gardeners fare well in well-drained evenly moist "humus-rich" garden soils like many in the related

Monkshood and other members of the genus ''Aconitum'' contain substantial amounts of the highly toxic

Monkshood and other members of the genus ''Aconitum'' contain substantial amounts of the highly toxic

Aconite was described in Greek and Roman

Aconite was described in Greek and Roman

Genetic analysis suggests that ''Aconitum'' as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within ''

Genetic analysis suggests that ''Aconitum'' as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within ''

File:Aconitum napellus01.jpg, ''

James Grout: ''Aconite Poisoning''

part of the ''Encyclopædia Romana''

Photographs of Aconite plants

Jepson Eflora entry for Aconitum

{{Authority control Neurotoxins Plant toxins Ranunculaceae genera

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of over 250 species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of flowering plants belonging to the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (, buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family (biology), family of over 2,000 known species of flowering plants in 43 genera, distributed worldwide.

The largest genera are ''Ranunculus'' (600 spec ...

. These herbaceous perennial plant

In horticulture, the term perennial (''wikt:per-#Prefix, per-'' + ''wikt:-ennial#Suffix, -ennial'', "through the year") is used to differentiate a plant from shorter-lived annual plant, annuals and biennial plant, biennials. It has thus been d ...

s are chiefly native

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

to the mountainous parts of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

in North America, Europe, and Asia, growing in the moisture-retentive but well-draining soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

s of mountain meadows.

Most ''Aconitum'' species are extremely poisonous and must be handled very carefully. Several ''Aconitum'' hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two diff ...

s, such as the Arendsii form of ''Aconitum carmichaelii

''Aconitum carmichaelii'' is a species of flowering plant of the genus ''Aconitum'', family Ranunculaceae. It is native to East Asia and eastern Russia. It is commonly known as Chinese aconite, Carmichael's monkshood or Chinese wolfsbane. In Mand ...

'', have won gardening awards—such as the Royal Horticultural Society

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), founded in 1804 as the Horticultural Society of London, is the UK's leading gardening charity.

The RHS promotes horticulture through its five gardens at Wisley (Surrey), Hyde Hall (Essex), Harlow Carr ...

's Award of Garden Merit

The Award of Garden Merit (AGM) is a long-established award for plants by the British Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). It is based on assessment of the plants' performance under UK growing conditions.

It includes the full range of cultivated p ...

. Some are used by florists.

Etymology

The name ''aconitum'' comes from the Greek word , which may derive from the Greek ''akon'' for dart or

The name ''aconitum'' comes from the Greek word , which may derive from the Greek ''akon'' for dart or javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the sling ...

, the tips of which were poisoned with the substance, or from ''akonae'', because of the rocky ground on which the plant was thought to grow. The Greek name ''lycoctonum'', which translates literally to "wolf's bane

Bane may refer to:

Fictional characters

* Bane (DC Comics), an adversary of Batman

* Bane (''Harry Potter''), a centaur in the ''Harry Potter'' series

* Bane (''The Matrix''), a character in the ''Matrix'' film trilogy

* Bane the Druid, a Gua ...

", is thought to indicate the use of its juice to poison arrows or baits used to kill wolves. The English name monkshood refers to the cylindrical helmet, called the galea, distinguishing the flower.

Description

The dark green leaves of ''Aconitum'' species lackstipules

In botany, a stipule is an outgrowth typically borne on both sides (sometimes on just one side) of the base of a leafstalk (the petiole). They are primarily found among dicots and rare among monocots. Stipules are considered part of the anatomy ...

. They are palmate

The following terms are used to describe leaf morphology in the description and taxonomy of plants. Leaves may be simple (that is, the leaf blade or 'lamina' is undivided) or compound (that is, the leaf blade is divided into two or more leaflets ...

or deeply palmately lobed with five to seven segments. Each segment again is trilobed with coarse sharp teeth. The leaves have a spiral (alternate) arrangement. The lower leaves have long petioles.

The tall, erect stem is crowned by

The tall, erect stem is crowned by raceme

A raceme () or racemoid is an unbranched, indeterminate growth, indeterminate type of inflorescence bearing flowers having short floral stalks along the shoots that bear the flowers. The oldest flowers grow close to the base and new flowers are ...

s of large blue, purple, white, yellow, or pink zygomorphic

Floral symmetry describes whether, and how, a flower, in particular its perianth, can be divided into two or more identical or mirror-image parts.

Uncommonly, flowers may have no axis of symmetry at all, typically because their parts are spir ...

flowers with numerous stamen

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

s. They are distinguishable by having one of the five petaloid

Petals are modified leaves that form an inner whorl surrounding the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often brightly coloured or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. All of the petals of a flower are collectively known as the ''coroll ...

sepal

A sepal () is a part of the flower of angiosperms (flowering plants). Usually green, sepals typically function as protection for the flower in bud, and often as support for the petals when in bloom., p. 106

Etymology

The term ''sepalum'' ...

s (the posterior one), called the galea, in the form of a cylindrical helmet, hence the English name monkshood. Two to 10 petal

Petals are modified leaves that form an inner whorl surrounding the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often brightly coloured or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. All of the petals of a flower are collectively known as the ''corol ...

s are present. The two upper petals are large and are placed under the hood of the calyx and are supported on long stalks. They have a hollow spur at their apex, containing the nectar

Nectar is a viscous, sugar-rich liquid produced by Plant, plants in glands called nectaries, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollination, pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to an ...

. The other petals are small and scale-like or nonforming. The three to five carpel

Gynoecium (; ; : gynoecia) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more ...

s are partially fused at the base.

The fruit is an aggregate of follicles, a follicle being a dry, many-seeded structure.

Unlike with many species from genera (and their hybrids) in ''Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (, buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family (biology), family of over 2,000 known species of flowering plants in 43 genera, distributed worldwide.

The largest genera are ''Ranunculus'' (600 spec ...

'' (and the related ''Papaveroideae

Papaveroideae is a subfamily of the family Papaveraceae (the poppy family).

Genera

* Subfamily Papaveroideae Eaton

:* Tribe Eschscholzieae Baill.

::* '' Dendromecon'' Benth. – California.

::* '' Eschscholzia'' Cham. – Western North Americ ...

'' subfamily), there are no double-flowered forms.

Color range

A medium to dark semi-saturated blue-purple is the typical flower color for ''Aconitum'' species. ''Aconitum'' species tend to be variable enough in form and color in the wild to cause debate and confusion among experts when it comes to species classification boundaries. The overall color range of the genus is rather limited, although the palette has been extended a small amount with hybridization. In the wild, some ''Aconitum'' blue-purple shades can be very dark. In cultivation the shades do not reach this level of depth. Aside from blue-purple—white, very pale greenish-white, creamy white, and pale greenish-yellow are also somewhat common in nature. Wine red (or red-purple) occurs in a hybrid of the climber ''Aconitum hemsleyanum''. There is a pale semi-saturated pink produced by cultivation as well as bicolor hybrids (e.g. white centers with blue-purple edges). Purplish shades range from very dark blue-purple to a very pale lavender that is quite greyish. The latter occurs in the "Stainless Steel" hybrid. Neutral blue (rather than purplish or greenish), greenish-blue, and intense blues, available in some related ''Delphinium

''Delphinium'' is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family (biology), family Ranunculaceae, native species, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. T ...

'' plants—particularly '' Delphinium grandiflorum''—do not occur in this genus. ''Aconitum'' plants that have purplish-blue flowers are often inaccurately referred to as having blue flowers, even though the purple tone dominates. If there are species with true (neutral) blue or greenish-blue flowers they are rare and do not occur in cultivation. Also unlike the genus ''Delphinium'', there are no bright red nor intense pink ''Aconitum'' flowers, as none known are pollinated by hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the Family (biology), biological family Trochilidae. With approximately 366 species and 113 genus, genera, they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but most species are found in Cen ...

. There are no orange-flowered varieties nor any that are green. ''Aconitum'' is typically more intense in color than ''Helleborus'' but less intense than ''Delphinium''. There are no blackish flowers in ''Aconitum'', unlike with ''Helleborus''.

Monkshood (''Aconitum napellus'') produces light indigo-blue flowers, while Wolf's Bane (''Aconitum vulparia'') produces whitish or straw-yellow flowers.

Horticultural trade morphology

The lack of double-flowered forms in the horticultural trade stands in contrast with the other genera of ''Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (, buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family (biology), family of over 2,000 known species of flowering plants in 43 genera, distributed worldwide.

The largest genera are ''Ranunculus'' (600 spec ...

'' used regularly in gardens. This includes one major genus that is known solely by most gardeners for a double-flowered form of one species—'' Ranunculus asiaticus'', known colloquially in the trade as "Ranunculus". The Ranunculus genus contains approximately 500 species. One other species of Ranunculus has seen minor use in gardens, the 'Flore Pleno' (doubled) form of ''Ranunculus acris

''Ranunculus acris'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Ranunculaceae, and is one of the more common buttercups across Europe and temperate Eurasia. Common names include meadow buttercup, tall buttercup, common buttercup and giant but ...

''. Doubled forms of ''Consolida

''Consolida'' is a genus of about 40 species of annual flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae, native to western Europe, the Mediterranean and Asia. Phylogenetic studies show that ''Consolida'' is actually an annual clade nested within the ...

'' and ''Delphinium

''Delphinium'' is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family (biology), family Ranunculaceae, native species, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. T ...

'' dominate the horticultural trade while single forms of ''Anemone

''Anemone'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the buttercup family Ranunculaceae. Plants of the genus are commonly called windflowers. They are native to the temperate and subtropical regions of all regions except Australia, New Zealand, and ...

'', ''Aquilegia

''Aquilegia'', commonly known as columbines, is a genus of perennial flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae (buttercups). The genus includes between 80 and 400 taxa (described species and subspecies) with natural Species distribution, rang ...

'', ''Clematis

''Clematis'' is a genus of about 380 species within the buttercup family, Ranunculaceae. Their garden hybrids and cultivars have been popular among gardeners, beginning with ''Clematis'' 'Jackmanii', a garden staple since 1862; more cultivars ...

'', ''Helleborus

Commonly known as hellebores (), the Eurasian genus ''Helleborus'' consists of approximately 20 species of herbaceous or evergreen perennial flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae, within which it gave its name to the tribe of Hellebo ...

'', ''Pulsatilla

The genus ''Pulsatilla'' contains about 40 species of herbaceous perennial plants native to meadows and prairies of North America, Europe, and Asia. Common names include pasque flower (or pasqueflower), wind flower, prairie crocus, Easter flower, ...

''—and the related ''Papaver

''Papaver'' is a genus of 70–100 species of frost-tolerant annual plant, annuals, biennial plant, biennials, and perennial plant, perennials native plant, native to temperateness, temperate and cold regions of Eurasia, Africa and North America ...

''—retain some popularity. No doubled forms of ''Aconitum'' are known.

Ecology

''Aconitum'' species have been recorded as food plant of the caterpillars of severalmoths

Moths are a group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not butterflies. They were previously classified as suborder Heterocera, but the group is paraphyletic with respect to butterflies (suborder Rhopalocera) a ...

. The yellow tiger moth ''Arctia flavia

''Arctia flavia'', the yellow tiger moth, is a moth of the family Erebidae. The species was first described by Johann Kaspar Füssli in 1779. It is found in the Alps above the tree level. It also occurs in Balkan mountains (Rila), European Russ ...

'', and the purple-shaded gem ''Euchalcia variabilis

''Euchalcia'' is a genus of moths of the family Noctuidae

The Noctuidae, commonly known as owlet moths, cutworms or armyworms, are a family (biology), family of moths. Taxonomically, they are considered the most controversial family in the sup ...

'' are at home on ''A. vulparia''. The engrailed ''Ectropis crepuscularia

The engrailed and small engrailed (''Ectropis crepuscularia'') are moths of the family Geometridae found from the British Isles through central and eastern Europe to the Russian Far East and Kazakhstan. The western Mediterranean and Asia Minor ...

'', yellow-tail '' Euproctis similis'', mouse moth '' Amphipyra tragopoginis'', pease blossom '' Periphanes delphinii'', and '' Mniotype bathensis'', have been observed feeding on ''A. napellus''. The purple-lined sallow ''Pyrrhia exprimens

''Pyrrhia exprimens'', the purple-lined sallow, is a moth of the family Noctuidae. The species was first described by Francis Walker (entomologist) in 1857. In North America it is found from Newfoundland and Labrador west across southern Canada ...

'', and '' Blepharita amica'' were found eating from ''A. septentrionale''. The dot moth '' Melanchra persicariae'' occurs both on ''A. septentrionale'' and ''A. intermedium''. The golden plusia '' Polychrysia moneta'' is hosted by ''A. vulparia'', ''A. napellus'', ''A. septentrionale'', and ''A. intermedium''. Other moths associated with ''Aconitum'' species include the wormwood pug ''Eupithecia absinthiata

The wormwood pug (''Eupithecia absinthiata'') is a moth of the family Geometridae. The species was first described by Carl Alexander Clerck in 1759. It is a common species across the Palearctic region as well as North America.

The wingspan is ...

'', satyr pug '' E. satyrata'', '' Aterpia charpentierana'', and '' A. corticana''. It is also the primary food source for the Old World bumblebees '' Bombus consobrinus'' and ''Bombus gerstaeckeri''.

Aconitum flowers are pollinated by long-tongued bumblebees. Bumblebees have the strength to open the flowers and reach the single nectary at the top of the flower on its inside. Some short-tongued bees will bore holes into the tops of the flowers to steal nectar. However, alkaloids in the nectar function as a deterrent for species unsuited to pollination. The effect is greater in certain species, such as ''Aconitum napellus

''Aconitum napellus'', monkshood, aconite, Venus' chariot or wolfsbane, is a species of highly toxic flowering plants in the genus ''Aconitum'' of the family Ranunculaceae, native and endemic to western and central Europe. It is an herbaceous pe ...

'', than in others, such as '' Aconitum lycoctonum''. Unlike the species with blue-purple flowers such as ''A. napellus'', ''A. lycoctonum''—which has off-white to pale yellow flowers, has been found to be a nectar source for butterflies. This is likely due to the nectary flowers of the latter being more easily reachable by the butterflies; however, the differing alkaloid character of the two plants may also play a significant role or be the primary influence.

Cultivation

The species typically utilized by gardeners fare well in well-drained evenly moist "humus-rich" garden soils like many in the related

The species typically utilized by gardeners fare well in well-drained evenly moist "humus-rich" garden soils like many in the related Helleborus

Commonly known as hellebores (), the Eurasian genus ''Helleborus'' consists of approximately 20 species of herbaceous or evergreen perennial flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae, within which it gave its name to the tribe of Hellebo ...

and Delphinium

''Delphinium'' is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family (biology), family Ranunculaceae, native species, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. T ...

genera, and can grow in the partial shade. Species not used in gardens tend to require more exacting conditions (e.g. ''Aconitum noveboracense

''Aconitum noveboracense'', also known as northern blue monkshood or northern wild monkshood, is a flowering plant belonging to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae). Members of its genus (''Aconitum'') are also known as wolfsbane.

''A. novebo ...

''). Most ''Aconitum'' species prefer to have their roots cool and moist, with the majority of the leaves exposed to sun, like the related ''Clematis

''Clematis'' is a genus of about 380 species within the buttercup family, Ranunculaceae. Their garden hybrids and cultivars have been popular among gardeners, beginning with ''Clematis'' 'Jackmanii', a garden staple since 1862; more cultivars ...

''. ''Aconitum'' species can be propagated by divisions of the root or by seeds, with care taken to avoid leaving pieces of the root where livestock might be poisoned. All parts of these plants should be handled while wearing protective disposable gloves. ''Aconitum'' plants are typically much longer-lived than the closely related delphinium plants, putting less energy into floral reproduction. As a result, they are not described as being "heavy feeders" (needing a higher quantity of fertilizer versus most other flowering plants)—unlike gardeners' delphiniums. As with most in the ''Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (, buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family (biology), family of over 2,000 known species of flowering plants in 43 genera, distributed worldwide.

The largest genera are ''Ranunculus'' (600 spec ...

'' and ''Papaveraceae

The Papaveraceae, informally known as the poppy family, are an economically important family (biology), family of about 42 genera and approximately 775 known species of flowering plants in the order Ranunculales. The family is cosmopolitan dis ...

'' families, they dislike root disturbance. As with most in Ranunculaceae, seeds that are not planted soon after harvesting should be stored moist-packed in vermiculite

Vermiculite is a hydrous phyllosilicate mineral which undergoes significant expansion when heated. Exfoliation occurs when the mineral is heated sufficiently; commercial furnaces can routinely produce this effect. Vermiculite forms by the weathe ...

to avoid dormancy and viability issues. The German seed company Jelitto offers "Gold Nugget" seeds that are advertised as utilizing a coating that enables the seed to germinate immediately, bypassing the double dormancy defect (from a typical gardener's point of view) ''Aconitum''—and many other species in Ranunculaceae genera—use as a reproductive strategy. By contrast, seeds that are not immediately planted or moist-packed are described as perhaps taking as long as two years to germinate, being prone to very erratic germination (in terms of time required per seed), and comparatively quick seed viability loss (e.g. ''Adonis

In Greek mythology, Adonis (; ) was the mortal lover of the goddesses Aphrodite and Persephone. He was considered to be the ideal of male beauty in classical antiquity.

The myth goes that Adonis was gored by a wild boar during a hunting trip ...

''). These issues are typical for many species in Ranunculaceae, such as ''Pulsatilla

The genus ''Pulsatilla'' contains about 40 species of herbaceous perennial plants native to meadows and prairies of North America, Europe, and Asia. Common names include pasque flower (or pasqueflower), wind flower, prairie crocus, Easter flower, ...

'' (pasqueflower

The genus ''Pulsatilla'' contains about 40 species of herbaceous perennial plants native to meadows and prairies of North America, Europe, and Asia. Common names include pasque flower (or pasqueflower), wind flower, prairie crocus, Easter flower, ...

).

Award-winning hybrids

In the UK, the following have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit: * ''A.'' × ''cammarum'' 'Bicolor' * ''A. carmichaelii'' 'Arendsii' * ''A. carmichaelii'' 'Kelmscott' * ''A.'' 'Bressingham Spire' * ''A.'' 'Spark's Variety' * ''A.'' 'Stainless Steel'Toxicology

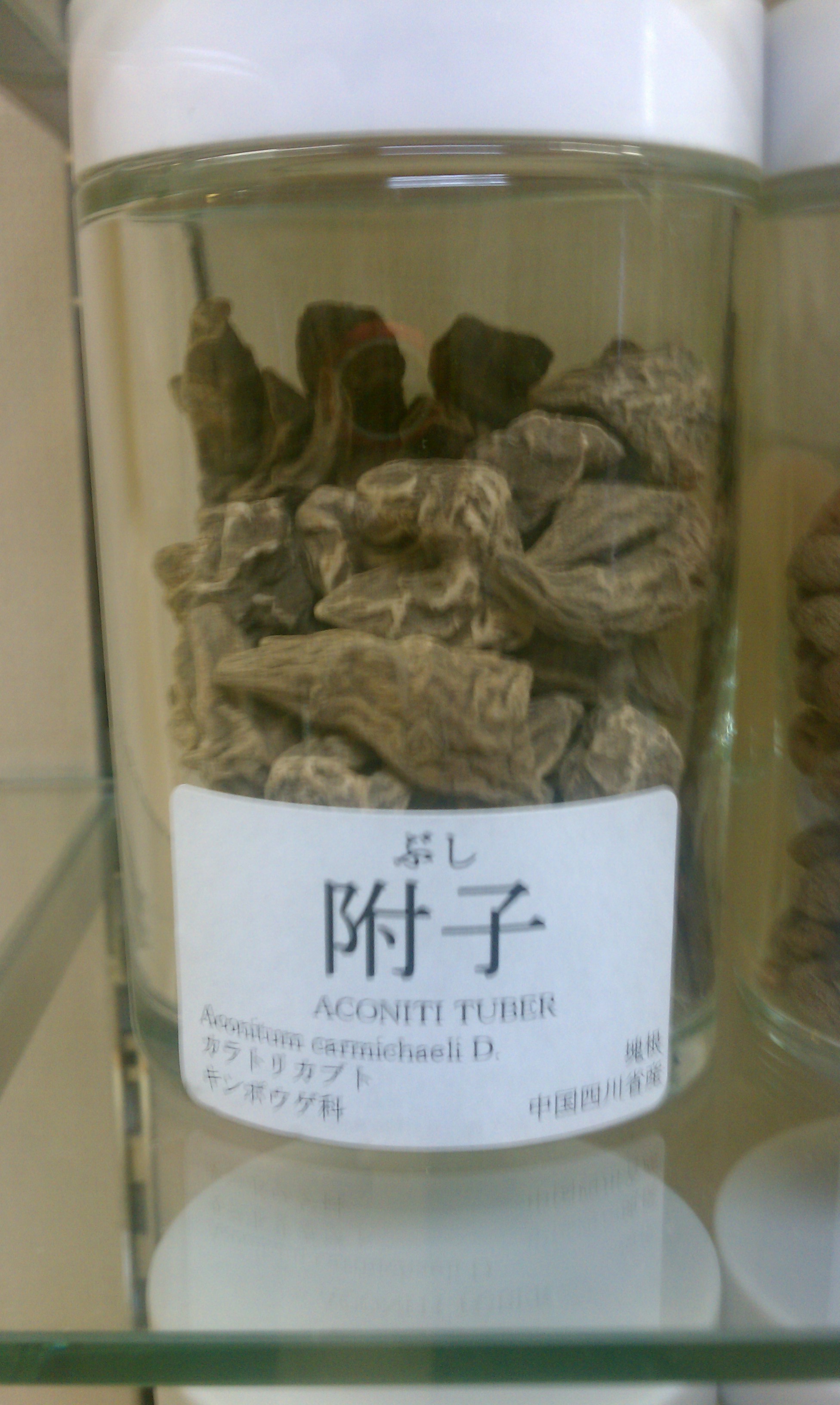

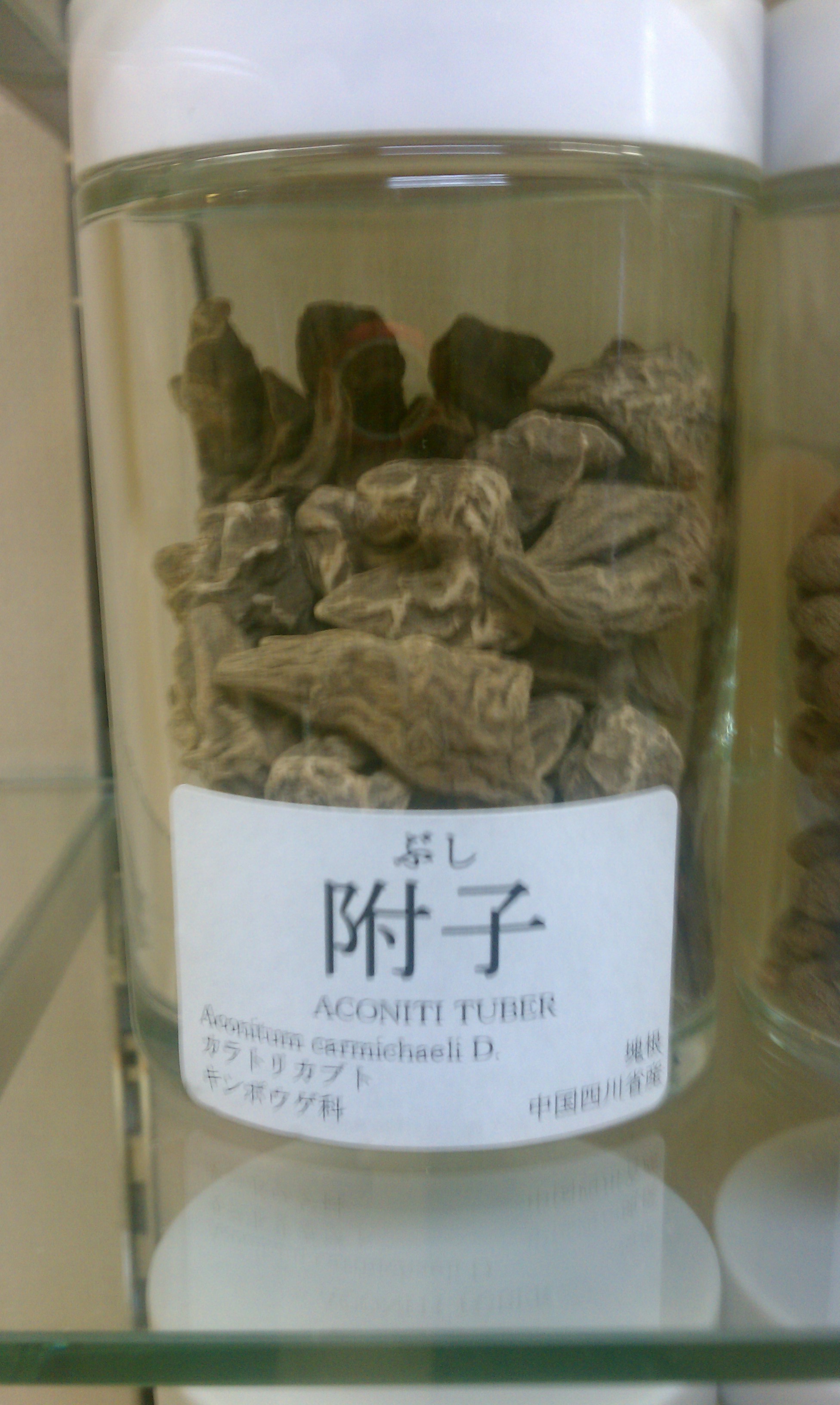

Monkshood and other members of the genus ''Aconitum'' contain substantial amounts of the highly toxic

Monkshood and other members of the genus ''Aconitum'' contain substantial amounts of the highly toxic aconitine

Aconitine is an alkaloid toxin produced by various plant species belonging to the genus ''Aconitum'' (family Ranunculaceae), commonly known by the names wolfsbane and monkshood. Aconitine is notorious for its toxic properties.

Structure and rea ...

and related alkaloids, especially in their roots and tubers. As little as 2 mg of aconitine or 1 g of plant may cause death from respiratory paralysis or heart failure.

Aconitine is a potent neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nervous tissue, nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insult (medical), insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function ...

and cardiotoxin that causes persistent depolarization of neuronal sodium channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell (biology), cell's cell membrane, membrane. They belong to the Cation channel superfamily, superfamily of cation channels.

Classific ...

s in tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an Order (biology), order that includes Tetraodontidae, pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Alt ...

-sensitive tissues. The influx of sodium through these channels and the delay in their repolarization increases their excitability and may lead to diarrhea, convulsions, ventricular arrhythmia

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, are irregularities in the heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. Essentially, this is anything but normal sinus rhythm. A resting heart rate that is too fast – above 100 beats ...

, and death.

Marked symptoms may appear almost immediately, usually not later than one hour, and "with large doses death is almost instantaneous". Death usually occurs within two to six hours in fatal poisoning (20 to 40 ml of tincture

A tincture is typically an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol (ethyl alcohol). Solvent concentrations of 25–60% are common, but may run as high as 90%.Groot Handboek Geneeskrachtige Planten by Geert Verhelst In chemistr ...

may prove fatal).''The Extra Pharmacopoeia Martindale''. Vol. 1, 24th edition. London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1958, page 38. The initial signs are gastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

, including nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

, and diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

. This is followed by a sensation of burning, tingling, and numbness in the mouth and face, and of burning in the abdomen. In severe poisonings, pronounced motor weakness occurs and cutaneous sensations of tingling and numbness spread to the limbs. Cardiovascular

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart a ...

features include hypotension

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is ...

, sinus bradycardia

Sinus bradycardia is a sinus rhythm with a reduced rate of electrical discharge from the sinoatrial node, resulting in a bradycardia, a heart rate that is lower than the normal range (60–100 beats per minute for adult humans).

Signs and sympt ...

, and ventricular arrhythmia

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, are irregularities in the cardiac cycle, heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. Essentially, this is anything but normal sinus rhythm. A resting heart rate that is too fast – ab ...

s. Other features may include sweating, dizziness, difficulty in breathing, headache, and confusion. The main causes of death are ventricular arrhythmias and asystole, or paralysis of the heart or respiratory center. The only ''post mortem'' signs are those of asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

.

Treatment of poisoning is mainly supportive. All patients require close monitoring of blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of Circulatory system, circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term ...

and cardiac rhythm

The cardiac conduction system (CCS, also called the electrical conduction system of the heart) transmits the signals generated by the sinoatrial node – the heart's pacemaker, to cause the heart muscle to contract, and pump blood through the ...

. Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal

"Activated" is a song by English singer Cher Lloyd. It was released on 22 July 2016 through Vixen Records. The song was made available to stream exclusively on ''Rolling Stone'' a day before to release (on 21 July 2016).

Background

In an inter ...

can be used if given within one hour of ingestion. The major physiological antidote is atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically give ...

, which is used to treat bradycardia. Other drugs used for ventricular arrhythmia include lidocaine

Lidocaine, also known as lignocaine and sold under the brand name Xylocaine among others, is a local anesthetic of the amino amide type. It is also used to treat ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. When used for local anae ...

, amiodarone

Amiodarone is an antiarrhythmic medication used to treat and prevent a number of types of cardiac dysrhythmias. This includes ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and wide complex tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and paroxys ...

, bretylium

Bretylium (also bretylium tosylate) is an antiarrhythmic agent. It blocks the release of noradrenaline from nerve terminals. In effect, it decreases output from the peripheral sympathetic nervous system. It also acts by blocking K+ channels and ...

, flecainide

Flecainide is a medication used to prevent and treat abnormally fast heart rates. This includes ventricular and supraventricular tachycardias. Its use is only recommended in those with dangerous arrhythmias or when significant symptoms cannot b ...

, procainamide

Procainamide (PCA) is a medication of the antiarrhythmic class used for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. It is a sodium channel blocker of cardiomyocytes; thus it is classified by the Vaughan Williams classification system as class Ia. ...

, and mexiletine

Mexiletine ( INN; sold under the brand names Mexitil and Namuscla) is a medication used to treat abnormal heart rhythms, chronic pain, and some causes of muscle stiffness. Common side effects include abdominal pain, chest discomfort, drowsiness, ...

. Cardiopulmonary bypass

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) or heart-lung machine, also called the pump or CPB pump, is a machine that temporarily takes over the function of the heart and lungs during open-heart surgery by maintaining the circulation of blood and oxygen throug ...

is used if symptoms are refractory to treatment with these drugs. Successful use of charcoal hemoperfusion

Hemoperfusion or hæmoperfusion (see spelling differences) is a method of filtering the blood extracorporeally (that is, outside the body) to remove a toxin. As with other extracorporeal methods, such as hemodialysis (HD), hemofiltration (HF), an ...

has been claimed in patients with severe aconitine poisoning.

Mild toxicity (headache, nausea and palpitations) as well as severe toxicity may be experienced from skin contact. Paraesthesia

Paresthesia is a sensation of the skin that may feel like numbness (''hypoesthesia''), tingling, pricking, chilling, or burning. It can be temporary or chronic and has many possible underlying causes. Paresthesia is usually painless and can oc ...

, including tingling and feelings of coldness in the face and extremities, is common in reports of toxicity.

Uses

Folk medicine

Aconite was described in Greek and Roman

Aconite was described in Greek and Roman folk medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) refers to the knowledge, skills, and practices rooted in the cultural beliefs of various societies, especially Indigenous groups, used for maintaining health and treatin ...

by Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides (, ; 40–90 AD), "the father of pharmacognosy", was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of (in the original , , both meaning "On Materia medica, Medical Material") , a 5-volume Greek encyclopedic phar ...

, and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, Folk medicinal use of ''Aconitum'' species is practiced in some parts of Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

.

''Aconitum chasmanthum'' is listed as critically endangered, ''Aconitum heterophyllum'' as endangered, and ''Aconitum violaceum'' as vulnerable due to overcollection for use as an herbal medicine

Herbal medicine (also called herbalism, phytomedicine or phytotherapy) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. Scientific evidence for the effectiveness of many herbal treatments ...

.

A producer of Yunnan Baiyao, a traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medicine, alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. A large share of its claims are pseudoscientific, with the majority of treatments having no robust evidence ...

remedy, has disclosed the remedy contains aconite.

As a poison

The roots of ''A. ferox'' supply theNepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

ese poison called ''bikh'', ''bish'', or ''nabee''. It contains large quantities of the alkaloid pseudaconitine, which is a deadly poison

A poison is any chemical substance that is harmful or lethal to living organisms. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figurati ...

. The root of ''A. luridum'', of the Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than 100 pea ...

, is said to be as poisonous as that of ''A. ferox'' or ''A. napellus''.

Several species of ''Aconitum'' have been used as arrow poisons. The Minaro in Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory and constitutes an eastern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a Kashmir#Kashmir dispute, dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947 and India an ...

use ''A. napellus'' on their arrows to hunt ibex

An ibex ( : ibex, ibexes or ibices) is any of several species of wild goat (genus ''Capra''), distinguished by the male's large recurved horns, which are transversely ridged in front. Ibex are found in Eurasia, North Africa and East Africa.

T ...

, while the Ainu in Japan used a species of ''Aconitum'' to hunt bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

as did the Matagi

The are traditional winter hunters of the Tōhoku region of northern Japan, most famously today in the Ani area in Akita Prefecture, which is known for the Akita dogs. Afterwards, they spread to the Shirakami-Sanchi forest between Akita and ...

hunters of the same region before their adoption of firearms. The Chinese also used ''Aconitum'' poisons both for hunting and for warfare. ''Aconitum'' poisons were used by the Aleut

Aleuts ( ; (west) or (east) ) are the Indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleuts and the islands are politically divided between the US state of Alaska ...

s of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

's Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

for hunting whales. Usually, one man in a kayak

]

A kayak is a small, narrow human-powered watercraft typically propelled by means of a long, double-bladed paddle. The word ''kayak'' originates from the Inuktitut word '' qajaq'' (). In British English, the kayak is also considered to be ...

armed with a poison-tipped lance would hunt the whale, paralyzing it with the poison and causing it to drown. ''Aconitum'' tipped arrows are also described in the Rig Veda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

.

It has, albeit rarely, been hypothesized that Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

was executed via an extract from an ''Aconitum'' species, such as ''Aconitum napellus

''Aconitum napellus'', monkshood, aconite, Venus' chariot or wolfsbane, is a species of highly toxic flowering plants in the genus ''Aconitum'' of the family Ranunculaceae, native and endemic to western and central Europe. It is an herbaceous pe ...

'', rather than via hemlock, ''Conium maculatum

''Conium maculatum'', commonly known as hemlock (British English) or poison hemlock (American English), is a highly poisonous flowering plant in the carrot family Apiaceae, native to Europe and North Africa. It is Herbaceous plant, herbaceous, wi ...

''. ''Aconitum'' was commonly used by the ancient Greeks as an arrow poison but can be used for other forms of poisoning. It has been hypothesized that Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

and Ptolemy XIV Philopator

Ptolemy XIV Philopator (, ; c. 59 – 44 BC) was a Pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, who reigned from 47 until his death in 44 BC.

Biography

Following the death of his older brother Ptolemy XIII of Egypt on January 13, 47 BC, and accor ...

were murdered via aconite.

In a review of Alisha Rankin's ''The Poison Trials'', Alison Abbott, writing in '' Nature'', reports Rankin's proposal of 1524 as the first human trial with a control arm

In automotive suspension, a control arm, also known as an A-arm, is a hinged suspension link between the chassis and the suspension upright or hub that carries the wheel. In simple terms, it governs a wheel's vertical travel, allowing it to mo ...

, indicating the book's description of a 16th century source presenting Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate of ...

poisoning a pair of prisoners with aconite-laced marzipan

Marzipan is a confectionery, confection consisting primarily of sugar and almond meal (ground almonds), sometimes augmented with almond oil or extract.

It is often made into Confectionery, sweets; common uses are chocolate-covered marzipan and ...

, testing an antidote on one that survived, leaving the untreated prisoner to suffer a painful death.

In April 2021, the president of Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

, Sadyr Japarov

Sadyr Nurgojo uulu Japarov (born 6 December 1968) is a Kyrgyzstani politician, diplomat, and oligarch who has been serving as the sixth president of Kyrgyzstan since 28 January 2021. He previously served as the 22nd prime minister in the 2020 ...

, promoted aconite root as a treatment for COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. In January 2020, the disease spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The symptoms of COVID‑19 can vary but often include fever ...

. Subsequently, at least four people were admitted to hospital suffering from poisoning. Facebook

Facebook is a social media and social networking service owned by the American technology conglomerate Meta Platforms, Meta. Created in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with four other Harvard College students and roommates, Eduardo Saverin, Andre ...

had previously removed the President's posts advocating use of the substance, saying "We've removed this post as we do not allow anyone, including elected officials, to share misinformation

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. Misinformation and disinformation are not interchangeable terms: misinformation can exist with or without specific malicious intent, whereas disinformation is distinct in that the information ...

that could lead to imminent physical harm or spread false claims about how to cure or prevent COVID-19".

Taxonomy

Genetic analysis suggests that ''Aconitum'' as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within ''

Genetic analysis suggests that ''Aconitum'' as it was delineated before the 21st century is nested within ''Delphinium

''Delphinium'' is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family (biology), family Ranunculaceae, native species, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. T ...

'' ''sensu lato'', that also includes ''Aconitella'', ''Consolida'', ''Delphinium staphisagria'', ''D. requini'', and ''D. pictum''. Further genetic analysis has shown that the only species of the subgenus "''Aconitum (Gymnaconitum)'', "''A. gymnandrum'', is sister to the group that consists of ''Delphinium (Delphinium)'', ''Delphinium (Delphinastrum)'', and "''Consolida'' plus "''Aconitella''. To make ''Aconitum'' monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

, "''A. gymnandrum'' has now been reassigned to a new genus, '' Gymnaconitum''. To make ''Delphinium'' monophyletic, the new genus ''Staphisagria'' was erected containing ''S. staphisagria'', ''S. requini'', and ''S. pictum''.

Selected species

* '' Aconitum anthora'' (yellow monkshood) * '' Aconitum anthoroideum'' * '' Aconitum bucovinense'' * ''Aconitum carmichaelii

''Aconitum carmichaelii'' is a species of flowering plant of the genus ''Aconitum'', family Ranunculaceae. It is native to East Asia and eastern Russia. It is commonly known as Chinese aconite, Carmichael's monkshood or Chinese wolfsbane. In Mand ...

'' (Carmichael's monkshood)

* '' Aconitum columbianum'' (western monkshood)

* '' Aconitum coreanum''(Korean monkshood)

* '' Aconitum degenii'' (branched monkshood)

* '' Aconitum delphinifolium'' (larkspurleaf monkshood)

* '' Aconitum ferox'' (Indian aconite)

* '' Aconitum firmum''

* '' Aconitum fischeri'' (Fischer monkshood)

* '' Aconitum flavum'' (Fluff iron hammer)

* '' Aconitum hemsleyanum'' (climbing monkshood)

* '' Aconitum henryi'' (Sparks variety monkshood)

* '' Aconitum heterophyllum''

* '' Aconitum infectum'' (Arizona monkshood)

* '' Aconitum jacquinii'' (synonym of '' A. anthora'')

* ''Aconitum koreanum

''Aconitum coreanum'', known as Korean monkshood, is one of the species of ''Aconitum''. It is one of the crude botanical drugs that has been applied in Chinese medicine during past decades.

Ecology

''Aconitum coreanum'' is a perennial shrub w ...

'' (synonym of " Aconitum coreanum")

* '' Aconitum kusnezoffii'' (Kusnezoff monkshood)

* '' Aconitum lamarckii'' (northern wolfsbane)

* '' Aconitum lasiostomum''

* '' Aconitum lycoctonum'' (northern wolfsbane)

* '' Aconitum maximum'' (Kamchatka aconite)

* ''Aconitum napellus

''Aconitum napellus'', monkshood, aconite, Venus' chariot or wolfsbane, is a species of highly toxic flowering plants in the genus ''Aconitum'' of the family Ranunculaceae, native and endemic to western and central Europe. It is an herbaceous pe ...

''

* ''Aconitum noveboracense

''Aconitum noveboracense'', also known as northern blue monkshood or northern wild monkshood, is a flowering plant belonging to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae). Members of its genus (''Aconitum'') are also known as wolfsbane.

''A. novebo ...

'' (northern blue monkshood)

* '' Aconitum plicatum'' (garden monkshood)

* '' Aconitum reclinatum'' (trailing white monkshood)

* '' Aconitum rogoviczii''

* ''Aconitum septentrionale

''Aconitum lycoctonum'' (wolf's-bane or northern wolf's-bane) is a species of flowering plant in the genus ''Aconitum'', of the family Ranunculaceae, native to much of Europe and northern Asia.Flora Europaea''Aconitum lycoctonum''/ref> It is fou ...

''

* '' Aconitum soongaricum''

* '' Aconitum sukaczevii''

* '' Aconitum tauricum''

* '' Aconitum uncinatum'' (southern blue monkshood)

* ''Aconitum variegatum

''Aconitum variegatum'' is a species of flowering plant belonging to the family Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (, buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family (biology), family of over 2,000 known species of flowe ...

''

* '' Aconitum violaceum''

* '' Aconitum vulparia'' (wolf's bane)

Phylogeny

Classification of Zhang ''et al.'' 2024 (PCG): Classification of Yanfei 2023 ( cpDNA):In literature and popular culture

Aconite and wolfsbane have been understood to be poisonous from ancient times, and are frequently represented as such in literature. InGreek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

, the goddess Hecate

Hecate ( ; ) is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, or snakes, or accompanied by dogs, and in later periods depicted as three-formed or triple-bodied. She is variously associat ...

is said to have invented aconite, which Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarde ...

used to transform Arachne

Arachne (; from , cognate with Latin ) is the protagonist of a tale in classical mythology known primarily from the version told by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE–17 CE). In Book Six of his epic poem ''Metamorphoses'', Ovid recounts how ...

into a spider. Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; ; ) is the daughter of Aeëtes, King Aeëtes of Colchis. Medea is known in most stories as a sorceress, an accomplished "wiktionary:φαρμακεία, pharmakeía" (medicinal magic), and is often depicted as a high- ...

is also said to have attempted to poison Theseus

Theseus (, ; ) was a divine hero in Greek mythology, famous for slaying the Minotaur. The myths surrounding Theseus, his journeys, exploits, and friends, have provided material for storytelling throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes desc ...

with a cup of wine poisoned with wolf's bane.

In the poem ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' (, , ) is a Latin Narrative poetry, narrative poem from 8 Common Era, CE by the Ancient Rome, Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''Masterpiece, magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its Cre ...

'', Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

tells of the herb coming from the slavering mouth of Cerberus

In Greek mythology, Cerberus ( or ; ''Kérberos'' ), often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a polycephaly, multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Greek underworld, underworld to prevent the dead from leaving. He was the offspring o ...

, the three-headed dog that guarded the gates of Hades. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

supports the legend that aconite came from the saliva of the dog Cerberus when Hercules dragged him from the underworld. As the veterinary historian John Blaisdell has noted, symptoms of aconite

Aconite may refer to:

*''Aconitum'', a plant genus containing the monkshoods

*Aconitine

Aconitine is an alkaloid toxin produced by various plant species belonging to the genus ''Aconitum'' (family Ranunculaceae), commonly known by the names wo ...

poisoning in humans bear similarity to those of rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abn ...

: frothy saliva, impaired vision, vertigo, and finally, coma; thus, ancient Greeks could have believed that this poison, mythically born of Cerberus's lips, was literally the same as found inside the mouth of a rabid dog.

In popular culture

Early examples

As a well-known poison from ancient times, aconite (including as wolfsbane, in its various spellings) often found place in historical fiction. In '' I, Claudius'', Livia, wife of Augustus, was portrayed discussing the merits, antidotes, and use of aconite with a poisoner. It is the poison used by a murderer in the third ofthe Cadfael Chronicles

''The Cadfael Chronicles'' is a series of historical murder mysteries written by the English author Edith Pargeter (1913–1995) under the name Ellis Peters. Set in the 12th century in England during the Anarchy, the novels focus on a Welsh B ...

, ''Monk's Hood

''Monk's-Hood'' is a medieval mystery novel by Ellis Peters, set in December 1138. It is the third novel in The Cadfael Chronicles. It was first published in 1980 (1980 in literature).

It was adapted for television in 1994 by Central for I ...

'' by Ellis Peters

Edith Mary Pargeter (28 September 1913 – 14 October 1995), also known by her pen name Ellis Peters, was an English author of works in many categories, especially history and historical fiction, and was also honoured for her translations of ...

, published in 1980 and set in 1138 in Shrewsbury, England.

The kyōgen

is a form of traditional Japanese comic theater. It developed alongside '' Noh'', was performed along with ''Noh'' as an intermission of sorts between ''Noh'' acts on the same stage, and retains close links to ''Noh'' in the modern day; there ...

(traditional Japanese comedy) play , which is well-known and frequently taught in Japan, is centered on dried aconite root used for traditional Chinese medicine. Taken from Shasekishu, a 13th-century anthology collected by Mujū

Mujū Dōkyō (; 1 January 1227 – 9 November 1312), birth name Ichien Dōkyō, was a Buddhist monk of the Japanese Kamakura period. He is superficially considered a Rinzai monk by some due to his compilation of the '' Shasekishū'' and similar ...

, the story describes servants who decide that the dried aconite root is really sugar, and suffer unpleasant though nonlethal symptoms after eating it.

In the 16th century, Shakespeare, writing in ''Henry IV Part II'' Act 4 Scene 4, refers to aconite, alongside rash gunpowder, working as strongly as the "venom of suggestion" to break up close relationships.

20th century and later

An overdose of aconite was the method by which Rudolph Bloom, father ofLeopold Bloom

Leopold Paula Bloom is the fictional protagonist and hero of James Joyce's 1922 novel '' Ulysses''. His peregrinations and encounters in Dublin on 16 June 1904 mirror, on a more mundane and intimate scale, those of Ulysses/Odysseus in Homer's ...

in James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

's ''Ulysses

Ulysses is the Latin name for Odysseus, a legendary Greek hero recognized for his intelligence and cunning. He is famous for his long, adventurous journey home to Ithaca after the Trojan War, as narrated in Homer's Odyssey.

Ulysses may also refer ...

'', died by suicide.

In the 1931 classic horror film ''Dracula

''Dracula'' is an 1897 Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish author Bram Stoker. The narrative is Epistolary novel, related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist and opens ...

'' starring Bela Lugosi

Blaskó Béla Ferenc Dezső (; October 20, 1882 – August 16, 1956), better known by the stage name Bela Lugosi ( ; ), was a Hungarian–American actor. He was best remembered for portraying Count Dracula in the horror film classic Dracula (19 ...

as Count Dracula

Count Dracula () is the title character of Bram Stoker's 1897 gothic horror novel ''Dracula''. He is considered the prototypical and archetypal vampire in subsequent works of fiction. Aspects of the character are believed by some to have been i ...

and Helen Chandler

Helen Chandler (February 1, 1906 – April 30, 1965) was an American film and theatre actress, best known for playing Mina Seward in the 1931 horror film ''Dracula''.

Career

Chandler attended the Professional Children's School in New Yor ...

as Mina Seward, reference is made to wolf's bane (''aconitum''); towards the end of the film, "Van Helsing holds up a sprig of wolf's bane". Van Helsing

Professor Abraham Van Helsing () is a fictional character from the 1897 gothic horror novel ''Dracula'' written by Bram Stoker. Van Helsing is a Dutch polymath doctor with a wide range of interests and accomplishments, partly attested by the P ...

educates the nurse protecting Mina from Count Dracula to place sprigs of wolf's bane around Mina's neck for protection, instructing that wolf's bane, a plant that grows in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, is used by those dwelling there to protect themselves against vampires.

In the 1941 film '' The Wolf Man'' starring Lon Chaney Jr. and Claude Rains, the following poem is recited several times:Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolf-bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.In the 1943 French novel '' Our Lady of the Flowers'', the boy Culafroy eats "Napel aconite", so that the "Renaissance would take possession of the child through the mouth." Aconite and wolfsbane have also appeared in a references in modern settings. In the early 1980s, famed Spanish horror film star

Paul Naschy

Jacinto Molina Álvarez (September 6, 1934 – November 30, 2009) known by his stage name Paul Naschy, was a Spanish film actor, screenwriter, and director working primarily in horror films. His portrayals of numerous classic horror figures&md ...

named his production company "Aconito Films", an in-joke relating to the large number of werewolf movies he produced. In the 2003 Korean television series ''Dae Jang Geum

''Jewel in the Palace'' () is a 2003 South Korean historical drama television series directed by Lee Byung-hoon. It first aired on MBC from September 15, 2003, to March 23, 2004, where it was the top program with an average viewership rati ...

'', set in the 15th and 16th centuries, Choi put "wolf's bane" in the previous queen's food.

In the 1980 novel ''Monk's-Hood

''Monk's-Hood'' is a medieval mystery novel by Ellis Peters, set in December 1138. It is the third novel in The Cadfael Chronicles. It was first published in 1980 (1980 in literature).

It was adapted for television in 1994 by Central for ...

'', third in Ellis Peters

Edith Mary Pargeter (28 September 1913 – 14 October 1995), also known by her pen name Ellis Peters, was an English author of works in many categories, especially history and historical fiction, and was also honoured for her translations of ...

' series ''The Cadfael Chronicles

''The Cadfael Chronicles'' is a series of historical murder mysteries written by the English author Edith Pargeter (1913–1995) under the name Ellis Peters. Set in the 12th century in England during the Anarchy, the novels focus on a Welsh B ...

'' and set in 1138, a wealthy donator to Shrewsbury Abbey, Gervase Bonel, is murdered with stolen Monks-hood liniment

Liniment (from , meaning "to smear, Anointing, anoint"), also called embrocation and heat rub, is a medicated topical preparation for application to the skin. Some liniments have a viscosity similar to that of water; others are lotion or balm; s ...

prepared by the Abbey's herbalist Brother Cadfael, who needs to identify the true culprit to exonerate Bonel's stepson Edwin.

In the ''Harry Potter

''Harry Potter'' is a series of seven Fantasy literature, fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young Magician (fantasy), wizard, Harry Potter (character), Harry Potter, and his friends ...

'' series by J.K. Rowling

Joanne Rowling ( ; born 31 July 1965), known by her pen name , is a British author and philanthropist. She is the author of ''Harry Potter'', a seven-volume fantasy novel series published from 1997 to 2007. The series has sold over 600&nb ...

, describing aconitum is one of three questions that Professor Snape asks Harry Potter during his first Potions class in the first novel. Snape's preparations of the drug as a treatment for lycanthropy

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (from Ancient Greek ), is an individual who can shapeshifting, shapeshift into a wolf, or especially in modern film, a Shapeshifting, therianthropic Hybrid beasts in folklore, hybrid wol ...

are also an important plot point in the third novel.

In the TV series ''Dexter

Dexter may refer to:

People

* Dexter (given name)

* Dexter (surname)

* Dexter (singer), Brazilian rapper Marcos Fernandes de Omena (born 1973)

* Famous Dex, also known as Dexter, American rapper Dexter Tiewon Gore Jr. (born 1993)

Places United ...

'', serial killer Hannah McKay (a love interest of protagonist Dexter Morgan

Dexter Morgan (born Dexter Moser), also known as The Bay Harbor Butcher, is a fictional serial killer and the antihero protagonist of the ''Dexter'' book series written by Jeff Lindsay (writer), Jeff Lindsay, as well as the Dexter (TV series), tel ...

) has a history of using aconite to murder her victims.

This family of poisons makes a showing in S. M. Stirling's 2000 science fiction novel, '' On the Oceans of Eternity'', where a renegade warlord is poisoned with aconite-laced food by his own chief of internal security. In the 2000s television show ''Merlin

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an interferometer array of radio telescopes spread across England. The array is run from Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire by the University of Manchester on behalf of UK Re ...

'', the titular character attempts to poison Arthur with aconite while under a spell.

In the 2010s TV series ''Forever

Forever or 4ever may refer to:

Film and television Films

* ''Forever'' (1921 film), an American silent film by George Fitzmaurice

* ''Forever'' (1978 film), an American made-for-television romantic drama, based on the novel by Judy Blume

* '' ...

'', Dr. Henry Morgan identifies the plants in the villain's greenhouse as specifically ''Aconitum variegatum'', which he has used to create a poison to release into the ventilation system of Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central Terminal (GCT; also referred to as Grand Central Station or simply as Grand Central) is a commuter rail terminal station, terminal located at 42nd Street (Manhattan), 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York Ci ...

. In the television series ''Game of Thrones

''Game of Thrones'' is an American Fantasy television, fantasy Drama (film and television), drama television series created by David Benioff and for HBO. It is an adaptation of ''A Song of Ice and Fire'', a series of high fantasy novels by ...

'' (2011-2019), a Tywin Lannister's commander is assassinated by a dart, identified by Tywin as "Wolf's Bane" due to its scent. In the second season of the BBC drama ''Shakespeare and Hatherway'', episode 9, a tennis player is poisoned through the skin of his palm by aconite smeared on the handle of his racquet.

In the third season of "You," Love Quinn murders her first husband, James, after injecting him with Aconite after James asked for a divorce. Love admits to Joe (the protagonist) that she killed James "accidentally" and then tells Joe she poisoned him with Aconite through skin contact after he grabbed a knife to protect himself after he asks Love for a divorce. When Love approaches Joe (who is believed to be dying from Aconite and is "paralyzed"), he stabs her with a needle with his own mixture he created from Love's Aconite substance. Joe tells Love, while she is paralyzed, that he knew what was growing in their backyard and tells her, "You did this to yourself."

In the 2024 Netflix

Netflix is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service. The service primarily distributes original and acquired films and television shows from various genres, and it is available internationally in multiple lang ...

thriller ''Carry-On

The term hand luggage or cabin baggage (normally called carry-on in North America) refers to the type of luggage that passengers are allowed to carry along in the passenger compartment of a vehicle instead of a separate cargo compartment. Pass ...

'', the Traveller (played by Jason Bateman

Jason Kent Bateman (born January 14, 1969) is an American actor. He is known for his roles as Michael Bluth in the Fox Broadcasting Company, Fox / Netflix sitcom ''Arrested Development'' (2003–2019) and Marty Byrde in the Netflix crime drama s ...

) murders some of his targets by poisoning them with aconitum.

In mysticism

Wolf's bane is used as an analogy for the power of divine communion in ''Liber 65'' 1:13–16, one ofAleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley ( ; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, novelist, mountaineer, and painter. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pr ...

's ''Holy Books of Thelema

''The Holy Books of Thelema'' is a collection of 15 works by Aleister Crowley, the founder of Thelema, originally published in 1909 by Crowley under the title ', and later republished in 1983, together with a number of additional texts, under t ...

''. Wolf's bane is mentioned in one verse of Lady Gwen Thompson

Lady Gwen Thompson (September 16, 1928 – May 22, 1986) was the pseudonym of Phyllis Thompson, author and teacher of traditionalist initiatory witchcraft through her own organisation, the New England Covens of Traditionalist Witches.

Thomp ...

's 1974 poem "Rede of the Wiccae", a long version of the Wiccan Rede

The Wiccan Rede is a statement that provides the key moral system in the new religious movement of Wicca and certain other related witchcraft-based faiths. A common form of the Rede is "An ye harm none, do what ye will" which was taken from a ...

: "Widdershins go when Moon doth wane, And the werewolves howl by the dread wolfsbane."

Gallery

Aconitum napellus

''Aconitum napellus'', monkshood, aconite, Venus' chariot or wolfsbane, is a species of highly toxic flowering plants in the genus ''Aconitum'' of the family Ranunculaceae, native and endemic to western and central Europe. It is an herbaceous pe ...

''

File:Aconitum-reclinatum01.jpg, Trailing white monkshood (''A. reclinatum)''

File:Aconitum-uncinatum01.jpg, Southern blue monkshood (''A. uncinatum'')

File:Alaskan Monkshood Leaf.jpg, Wild Alaskan monkshood (''A. delphinifolium'') is a flowering species that belongs to the family Ranunculaceae. The picture was taken in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge

The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge is a wildlife habitat preserve located on the Kenai Peninsula of Alaska, United States. It is adjacent to Kenai Fjords National Park. This refuge was created in 1941 as the Kenai National Moose Range, but in ...

in Alaska.

See also

*Rufus T. Bush

Rufus Ter Bush (February 22, 1840 – September 15, 1890) was an American businessman, industrialist, and yachtsman. His notable testimony against Standard Oil's monopolistic practices through railroad rebates left a lasting impression, while th ...

, industrial tycoon who died of accidental aconite poisoning

References

External links

James Grout: ''Aconite Poisoning''

part of the ''Encyclopædia Romana''

Photographs of Aconite plants

Jepson Eflora entry for Aconitum

{{Authority control Neurotoxins Plant toxins Ranunculaceae genera