The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a

natural history museum on the

Upper West Side of

Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

in

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from

Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

, the museum complex comprises 21 interconnected buildings housing 45 permanent exhibition halls, in addition to a planetarium and a library. The museum collections contain about 32 million specimens

of plants, animals, fungi, fossils, minerals, rocks, meteorites, human remains, and human

cultural artifacts, as well as specialized collections for frozen tissue and genomic and astrophysical data, of which only a small fraction can be displayed at any given time. The museum occupies more than . AMNH has a full-time scientific staff of 225, sponsors over 120 special field expeditions each year, and averages about five million visits annually.

The AMNH is a private

501(c)(3) organization

A 501(c)(3) organization is a United States corporation, Trust (business), trust, unincorporated association or other type of organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(3) of Title 26 of the United States Code. It is one of ...

.

The naturalist

Albert S. Bickmore devised the idea for the American Museum of Natural History in 1861, and, after several years of advocacy, the museum opened within Central Park's

Arsenal on May 22, 1871. The museum's first purpose-built structure in Theodore Roosevelt Park was designed by

Calvert Vaux and

J. Wrey Mould and opened on December 22, 1877. Numerous wings have been added over the years, including the main entrance pavilion (named for

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

) in 1936 and the

Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000.

History

Founding

Early efforts

The naturalist

Albert S. Bickmore devised the idea for the American Museum of Natural History in 1861.

At the time, he was studying in

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

, at

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

's Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Observing that many European

natural history museums were in populous cities, Bickmore wrote in a biography: "Now New York is our city of greatest wealth and therefore probably the best location for the future museum of natural history for our whole land."

For several years, Bickmore lobbied for the establishment of a natural history museum in New York. Upon the end of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Bickmore asked numerous prominent New Yorkers, such as

William E. Dodge Jr., to sponsor his museum.

Although Dodge himself could not fund the museum at the time, he introduced the naturalist to

Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the father of future U.S. president

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

.

Calls for a natural history museum increased after

Barnum's American Museum burned down in 1868.

Eighteen prominent New Yorkers wrote a letter to the Central Park Commission that December, requesting the creation of a natural history museum in

Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

.

Central Park commissioner

Andrew Haswell Green indicated his support for the project in January 1869.

A board of trustees was created for the museum. The next month, Bickmore and

Joseph Hodges Choate drafted a

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

for the museum, which the board of trustees approved without any changes. It was in this charter that the "American Museum of Natural History" name was first used.

Bickmore said he wanted the museum's name to reflect his "expectation that our museum will ultimately become the leading institution of its kind in our country", similar to the

British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

Before the museum was established, Bickmore needed to secure approval from

Boss Tweed, leader of the powerful and corrupt

Tammany Hall political organization. The legislation to establish the American Museum of Natural History had to be signed by

John Thompson Hoffman, the governor of New York, who was associated with Tweed.

Creation and new building

Hoffman signed the legislation creating the museum on April 6, 1869,

with John David Wolfe as its first president.

Subsequently, the chairman of the AMNH's executive committee asked Green if the museum could use the top two stories of Central Park's

Arsenal, and Green approved the request in January 1870.

Insect specimens were placed on the lower level of the Arsenal,

while stones, fossils, mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles were placed on the upper level.

The museum opened within the Arsenal on May 22, 1871.

The AMNH became popular in the following years. The Arsenal location had 856,773 visitors in the first nine months of 1876 alone, more than the

British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

had recorded for all of 1874.

Meanwhile, the AMNH's directors had identified Manhattan Square (bounded by

Eighth Avenue/Central Park West, 81st Street,

Ninth Avenue/Columbus Avenue, and 77th Street) as a site for a permanent structure.

Several prominent New Yorkers had raised $500,000 to fund the construction of the new building. The city's park commissioners then reserved Manhattan Square as the site of the permanent museum, and another $200,000 was raised for the building fund.

Numerous dignitaries and officials, including U.S. president

Ulysses S. Grant, attended the museum's

groundbreaking ceremony on June 3, 1874.

The museum opened on December 22, 1877, with a ceremony attended by U.S. president

Rutherford B. Hayes.

The old exhibits were removed from the Arsenal in 1878, and the AMNH was debt-free by the next year.

19th century

Originally, the AMNH was accessed by a temporary bridge that crossed a ditch, and it was closed during Sundays. The museum's trustees voted in May 1881 to complete the approaches from

Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

,

and work began later that year.

The landscape changes were nearly complete by mid-1882,

and a bridge over Central Park West opened that November.

At this point, the AMNH's Manhattan Square building and the Arsenal could not physically fit any more objects, and the existing facilities, such as the 100-seat lecture hall, were insufficient to accommodate demand.

The trustees began discussing the possibility of opening the museum on Sundays in May 1885,

and the state legislature approved a bill permitting Sunday operations the next year.

Despite advocacy from the working class,

the trustees opposed Sunday operations because it would be expensive to do so.

At the time, the museum was open to the general public on Wednesdays through Saturdays, and it was open exclusively to members on Mondays and Tuesdays.

The museum's collections continued to grow during the 1880s,

and it hosted various lectures through the 19th century.

With several departments having been crowded out of the original building, New York state legislators introduced bills to expand the AMNH in early 1887;

thousands of teachers endorsed the legislation.

City parks engineer Montgomery A. Kellogg was directed to prepare plans for landscaping the site.

In March 1888, the trustees approved an entrance pavilion at the center of the 77th Street elevation.

The

New York City Board of Estimate began soliciting bids from general contractors in late 1889.

Many of the objects and specimens in the museum's collection could not be displayed until the annex was opened.

The original building was refurbished during 1890,

and the museum's library was transferred to the west wing that year.

The AMNH's trustees considered opening the museum on Sundays by February 1892

and stopped charging admission that July.

The museum began Sunday operations in August,

and the southern entrance pavilion opened that November.

Even with the new wing, there was still not enough space for the museum's collection.

The city's Park Board approved a new lecture hall in January 1893,

but the hall was postponed that May in favor of a wing extending east on 77th Street.

A contract to furnish the east wing was awarded in June 1894.

When the east wing was nearly completed in February 1895, the AMNH's trustees asked state legislators for $200,000 to build a wing extending west on 77th Street.

The east wing was still being furnished by August;

its ground floor opened that December.

The museum's funds and collections continued to grow during this time.

A hall of mammals opened within the museum in November 1896.

That year, the AMNH received approval to extend the east wing northward along Central Park West, creating an L-shaped structure.

Plans for an expanded east wing were approved in June 1897, and a contract was awarded two months later.

The museum's director

Morris K. Jesup also sponsored worldwide expeditions to obtain objects for the collection. By mid-1898, the west wing, the expanded east wing, and a lecture hall at the center of the museum were underway;

however, the project encountered delays due to a lack of city funding.

The west and east wings, with several exhibit halls, were nearly complete by late 1899, but the lecture hall had been delayed.

A hall dedicated to ancient Mexican art opened that December.

20th century

1900s to 1940s

The museum's 1,350-seat lecture hall opened in October 1900, as did the Native American and Mexican halls in the west wing.

During the 1900s, the AMNH sponsored several expeditions to grow its collection, including a trip to Mexico,

a trip to collect fauna from the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

,

a trip to collect art in China,

and an expedition to collect rocks in local caves. One such exhibition yielded a

brontosaurus skeleton, which was the centerpiece of the dinosaur hall that opened in February 1905.

In the early 1920s, museum president

Henry Fairfield Osborn planned a new entrance for the AMNH, which was to contain a memorial to

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. Also around that time, the New York state government formed a commission to study the feasibility of a Roosevelt memorial.

After a dispute over whether to put the memorial in

Albany or in New York City, the government of New York City offered a site next to the AMNH for consideration. The commission rejected a "conventional Greek mausoleum" design, instead opting to design a

triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

and hall in a Roman style. In 1925, the AMNH's trustees hosted an

architectural design competition, selecting

John Russell Pope to design the memorial hall.

Construction began in 1929,

and the trustees approved final plans the next year. J. Harry McNally was the

general contractor

A contractor (North American English) or builder (British English), is responsible for the day-to-day oversight of a construction site, management of vendors and trades, and the communication of information to all involved parties throughout the c ...

. Roosevelt's cousin, U.S. president

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, dedicated the memorial on January 19, 1936.

1950s to 1990s

The original building was later known as "Wing A". During the 1950s, the top floor was renovated into a library, being redecorated with what

Christopher Gray of ''The New York Times'' described as "dropped ceilings and the other usual insults".

The ten-story

Childs Frick Building, which contained the AMNH's fossil collection, was added to the museum in the 1970s.

The architect

Kevin Roche

Eamonn Kevin Roche (June 14, 1922 – March 1, 2019) was an Irish-born American Pritzker Prize-winning architect. Kevin Roche was the Archetype, archetypal Modern architecture, modernist and "member of an elite group of third generation modern ...

and his firm

Roche-Dinkeloo have been responsible for the master planning of the museum since the 1990s.

Various renovations to both the interior and exterior have been carried out. Renovations to the Dinosaur Hall were undertaken beginning in 1991,

and Roche-Dinkeloo designed the eight-story AMNH Library in 1992. The museum's Rose Center for Earth and Space was completed in 2000.

21st century

In 2001, the museum's lecture hall was renamed the Samuel J. and Ethel LeFrak Theater, after

Samuel J. LeFrak donated US$8 million to the AMNH.

The museum's south facade, spanning 77th Street from Central Park West to

Columbus Avenue, was cleaned and repaired, re-emerging in 2009. Steven Reichl, a spokesman for the museum, said that work would include restoring 650 black-cherry window frames and stone repairs. The museum's consultant on the latest renovation was

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., an architectural and engineering firm with headquarters in

Northbrook, Illinois.

The museum also restored the mural in Roosevelt Memorial Hall in 2010.

Richard Gilder Center

In 2014, the museum published plans for a $325 million, annex, the

Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, on the Columbus Avenue side. It was named after stockbroker and philanthropist

Richard Gilder.

On October 11, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously approved the expansion. Construction of the Gilder Center, which was expected to break ground the next year following design development and

Environmental Impact Statement stages, would entail demolition of three museum buildings built between 1874 and 1935.

The museum filed plans for the expansion in August 2017, but due to community opposition, construction did not start until June 2019.

On May 4, 2023, the Gilder Center opened,

and the museum had 1.5 million visitors over the next three months.

Native remains

In late 2023, the museum announced that it would stop displaying human remains from its collection. Despite the 1990 passage of the

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), as late as 2023, the AMNH held an estimated 1,900 Native American remains that had not been repatriated.

In January 2024, the museum closed a number of displays and the AMNH's Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains halls, or about 10,000 square feet.

The museum agreed to repatriate the remains that July.

Original structure

The original

Victorian Gothic building was designed by

Calvert Vaux and

J. Wrey Mould, both already closely identified with the architecture of Central Park.

Vaux and Mould's original plan was intended to complement the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the opposite side of Central Park.

The original building, as constructed, was at the center of the 77th Street

frontage and measured across;

it featured a gallery measuring long tall. This gallery contained a raised basement, three stories of exhibits, Venetian Gothic arches, and an attic with

dormers and a slate roof.

The rear of the gallery included two towers: one containing a stairwell and the other containing curators' rooms.

The original structure still exists but is hidden from view by the many buildings in the complex that today occupy most of Manhattan Square. The museum remains accessible through its 77th Street foyer, which has since been renamed the Grand Gallery.

The full plan called for twelve pavilions similar in design to the original building. Eight pavilions would have been arranged as the sides of a square, while the remaining four would be perpendicular to each other in the interior of the square. There were to be eight towers along the perimeter of the square, as well as a dome in the center, at the intersection of the four interior pavilions.

In each pavilion, there was to be a ground floor; the second floor was to contain a gallery; the third floor was to exhibit specimens; and the fourth floor was to be used for research.

Upon the intended completion of the master plan, the museum would measure from north to south and from west to east, including projections from the square.

The finished structure, with a ground area of over ,

would have been the largest building in North America, as well as the largest museum building in the world.

The master plan was never fully realized;

by 2015, the museum consisted of 25 separate buildings that were poorly connected.

The original building was soon eclipsed by the west and east wings of the southern frontage, designed by

J. Cleaveland Cady as a brownstone

neo-Romanesque structure.

It extends along West 77th Street, with corner towers tall. Its pink brownstone and granite, similar to that found at

Grindstone Island in the

St. Lawrence River, came from quarries at Picton Island, New York. The southern wing contains several halls ranging in size from to .

At the ends of either wings are rounded

turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Optical microscope#Objective turret (revolver or revolving nose piece), Objective turre ...

-like towers.

New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt

The main entrance hall on Central Park West is formally known as the New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt. Completed by

John Russell Pope in 1936, it is an over-scaled

Beaux-Arts monument to former U.S. president

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

.

The hall was originally supposed to have formed one end of an "Intermuseum Promenade" through Central Park, connecting with the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

to the east, but the promenade was never completed.

The memorial hall has a pink-granite facade, which is modeled after Roman arches.

In front of the hall on Central Park West is a terrace measuring long, as well as a series of steps. The main entrance consists of an arch measuring high.

The underside of the arch is a

coffered granite vestibule, which leads to a bronze, glass, and marble screen.

On either side of the arch are niches that contain sculptures of a bison and a bear. It is flanked by two pairs of columns, which are topped by figures of American explorers

John James Audubon,

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (, 1734September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyo ...

,

Meriwether Lewis, and

William Clark.

These figures were sculpted by

James Earle Fraser and are about high. In the attic above the main archway, there is an inscription describing Roosevelt's accomplishments.

The words "Truth", "Knowledge", and "Vision" are carved into the

entablature under this inscription.

Fraser also designed an

equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt

''Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt'' is a 1939 bronze sculpture by James Earle Fraser (sculptor), James Earle Fraser. It was located on public park land at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The equestrian statue dep ...

, flanked by a Native American and an African American, which originally stood outside the memorial hall. In the 21st century, the statue generated controversy due to its subordinate depiction of these figures behind Roosevelt. This prompted AMNH officials to announce in 2020 that they would remove the statue.

The statue was removed in January 2022 and will be on a long-term loan to the

Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in North Dakota.

The interior of the Memorial Hall measures across, with a barrel-vaulted ceiling measuring tall.

The ceiling contains octagonal coffers, while the floors are made of mosaic marble tiles. The lowest of the walls are

wainscoted in marble, above which the walls of the memorial hall are made of limestone. The top of each wall contains a marble band and a

Corinthian entablature. Each of the Memorial Hall's four sides contains two red-marble columns, each measuring tall and rising from a

Botticino marble pedestal. There are rounded windows at

clerestory

A clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey; from Old French ''cler estor'') is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye-level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, a ''clerestory' ...

level on the north and south walls.

William Andrew MacKay designed three murals depicting important events in Roosevelt's life: the construction of the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

on the north wall, African exploration on the west wall, and the

Treaty of Portsmouth on the south wall.

The east and west walls, contain four quotes from Roosevelt under the headings "Nature", "Manhood", "Youth", and "The State".

The Memorial Hall originally connected to various classrooms, exhibition rooms, and a 600-person auditorium.

Directly underneath the Memorial Hall is an entrance to the

81st Street–Museum of Natural History station.

Today, the hall connects to the Akeley Hall of African Mammals and the Hall of Asian Mammals. The Memorial Hall contains four exhibits that describe Theodore Roosevelt's conservation activities in his youth, early adulthood, U.S. presidency, and post-presidency.

Mammal halls

Old World mammals

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

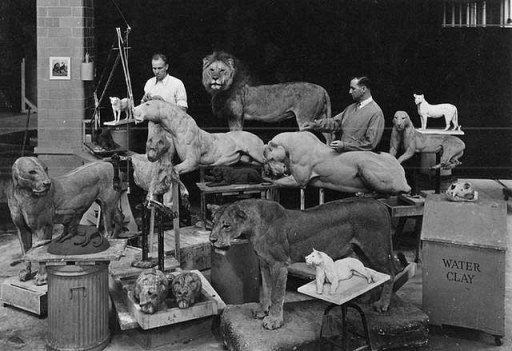

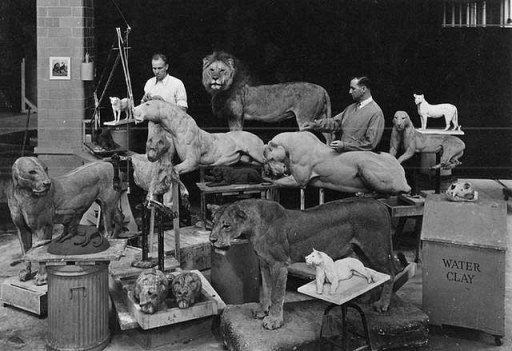

Named after taxidermist

Carl Akeley, the Akeley Hall of African Mammals is a two-story hall on the second floor, directly west of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It connects to the Hall of African Peoples to the west.

The Hall of African Mammals' 28 dioramas depict in meticulous detail the great range of ecosystems found in Africa and the mammals endemic to them. The centerpiece of the hall is a herd of eight

African elephants in a characteristic 'alarmed' formation.

Though the mammals are typically the main feature in the dioramas, birds and flora of the regions are occasionally featured as well. The hall in its current form was completed in 1936.

The Hall of African Mammals was first proposed to the museum by Carl Akeley around 1909; he proposed 40 dioramas featuring the rapidly vanishing landscapes and animals of Africa. Daniel Pomeroy, a trustee of the museum and partner at

J.P. Morgan & Co., offered investors the opportunity to accompany the museum's expeditions in Africa in exchange for funding.

Akeley began collecting specimens for the hall as early as 1909, famously encountering

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

in the midst of the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African expedition. On these early expeditions, Akeley was accompanied by his former apprentice in taxidermy,

James L. Clark, and artist,

William R. Leigh.

When Akeley returned to Africa to collect gorillas for the hall's first diorama, Clark remained behind and began scouring the country for artists to create the backgrounds. The eventual appearance of the first habitat groups impacted the design of other diorama halls, including Birds of the World, the Hall of North American Mammals, the

Vernay Hall of Southeast Asian Mammals, and the Hall of Oceanic Life.

After Akeley's unexpected death during the Eastman-Pomeroy expedition in 1926, responsibility of the hall's completion fell to James L. Clark, who hired architectural artist

James Perry Wilson in 1933 to assist Leigh in the painting of backgrounds. Wilson made many improvements on Leigh's techniques, including a range of methods to minimize the distortion caused by the dioramas' curved walls.

In 1936,

William Durant Campbell, a wealthy board member with a desire to see Africa, offered to fund several dioramas if allowed to obtain the specimens himself. Clark agreed to this arrangement, resulting in the acquisition of numerous large specimens.

Kane joined Leigh, Wilson, and several other artists in completing the hall's remaining dioramas.

Though construction of the hall was completed in 1936,

the dioramas gradually opened between the mid-1920s and early 1940s.

Hall of Asian Mammals

The Hall of Asian Mammals, sometimes referred to as the Vernay-Faunthorpe Hall of Asian Mammals, is directly south of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall.

It contains 8 complete dioramas, 4 partial dioramas, and 6 habitat groups of mammals and locations from

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

,

Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

,

Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, and

Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

. The hall opened in 1930 and, similar to the Akeley Hall of African Mammals, is centered around 2

Asian elephants. At one point, a

giant panda and

Siberian tiger

The Siberian tiger or Amur tiger is a population of the tiger subspecies ''Panthera tigris tigris'' native to Northeast China, the Russian Far East, and possibly North Korea. It once ranged throughout the Korea, Korean Peninsula, but currently ...

were also part of the Hall's collection, originally intended to be part of an adjoining Hall of North Asian Mammals (planned in the current location of Stout Hall of Asian Peoples). These specimens can currently be seen in the Hall of Biodiversity.

Specimens for the Hall of Asian Mammals were collected over six expeditions led by British-born antiques dealer

Arthur S. Vernay and Col.

John Faunthorpe (as noted by stylized plaques at both entrances). The expeditions were funded entirely by Vernay, who characterized the expense as a British tribute to American involvement in World War I. The first Vernay-Faunthorpe expedition took place in 1922, when many of the animals Vernay was seeking, such as the

Sumatran rhinoceros and

Asiatic lion, were facing the possibility of extinction. Vernay made many appeals to regional authorities to obtain hunting permits; in later museum-related expeditions headed by Vernay, these appeals helped the museum gain access to areas previously restricted to foreign visitors. Artist Clarence C. Rosenkranz accompanied the Vernay-Faunthorpe expeditions as field artist and painted the majority of the diorama backgrounds in the hall. These expeditions were also well documented in both photo and video, with enough footage of the first expedition to create a feature-length film, ''Hunting Tigers in India'' (1929).

New World mammals

Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals

The Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals is on the first floor, directly west of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall.

features 43 dioramas of various mammals of the American continent, north of tropical Mexico. Each diorama places focus on a particular species, ranging from the largest megafauna to the smaller rodents and carnivorans. Notable dioramas include the

Alaskan brown bears looking at a salmon after they scared off an otter, a pair of

wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

, a pair of

Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

n

jaguars, and dueling bull

Alaska moose.

The Hall of North American Mammals opened in 1942 with only ten dioramas. Another 16 dioramas were added in 1963. A massive restoration project began in late 2011 following a large donation from Jill and Lewis Bernard.

In October 2012 the hall was reopened as the Bernard Hall of North American Mammals.

=Hall of Small Mammals

=

The Hall of Small Mammals is an offshoot of the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals, directly to the west of the latter.

There are several small dioramas featuring small mammals found throughout North America, including

collared peccaries,

Abert's squirrel, and a

wolverine

The wolverine ( , ; ''Gulo gulo''), also called the carcajou or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species, member of the family Mustelidae. It is a muscular carnivore and a solitary animal. The w ...

.

Birds, reptiles, and amphibian halls

Sanford Hall of North American Birds

The Sanford Hall of North American birds is a one-story hall on the third floor, between the Hall of Primates and Akeley Hall's second level.

There are over 20 dioramas depicting birds from across North America in their native habitats.

At the far end of the hall are two large murals by ornithologist and artist

Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

The hall also has display cases devoted to large collections of

warblers,

owls, and

raptors.

Conceived by museum ornithologist

Frank Chapman, the Hall is named for Chapman's friend and amateur ornithologist

Leonard C. Sanford, who partially funded the hall and also donated the entirety of his own bird specimen collection to the museum. Construction began on the hall's dioramas as early as 1902, and the dioramas opened in 1909. They were the first to be exhibited in the museum and are the oldest still on display.

The hall was refurbished in 1962.

Although Chapman was not the first to create museum dioramas, he was the first to bring artists into the field with him in the hopes of capturing a specific location at a specific time. In contrast to the dramatic scenes that Akeley created for the African Hall, Chapman wanted his dioramas to evoke a scientific realism, ultimately serving as a historical record of habitats and species facing a high probability of extinction.

Each of Chapman's dioramas depicted a species, their nests, and of the surrounding habitat in each direction.

Hall of Birds of the World

The Hall of Birds of the World is on the south side of the second floor.

The global diversity of bird species is exhibited in this hall. 12 dioramas showcase various ecosystems around the world and provide a sample of the varieties of birds that live there. Example dioramas include

South Georgia

South Georgia is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. ...

featuring

king penguins and

skuas, the East African plains featuring

secretarybirds and

bustards, and the Australian outback featuring

honeyeater

The honeyeaters are a large and diverse family, Meliphagidae, of small to medium-sized birds. The family includes the Australian chats, myzomelas, friarbirds, wattlebirds, miners and melidectes. They are most common in Australia and New Gui ...

s,

cockatoos, and

kookaburras.

Whitney Memorial Hall of Oceanic Birds

The Whitney Memorial Wing, originally named after

Harry Payne Whitney and comprising 750,000 birds, opened in 1939.

Later known as the Hall of Oceanic Birds, it was completed and dedicated in 1953.

It was founded by Frank Chapman and Leonard C. Sanford, originally museum volunteers, who had gone forward with creation of a hall to feature birds of the Pacific islands. The hall was designed as a completely immersive collection of dioramas, including a circular display featuring

birds-of-paradise.

In 1998, the Butterfly Conservatory was installed inside the hall.

Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians

The Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians is near the southeast corner of the third floor.

It serves as an introduction to

herpetology

Herpetology (from Ancient Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (Gymnophiona)) and reptiles (in ...

, with many exhibits detailing reptile evolution, anatomy, diversity, reproduction, and behavior. Notable exhibits include a

Komodo dragon group, an

American alligator,

Lonesome George, the last

Pinta Island tortoise, and

poison dart frogs.

In 1926,

W. Douglas Burden, F.J. Defosse, and

Emmett Reid Dunn collected specimens of the Komodo Dragon for the museum. Burden's chapter "The Komodo Dragon", in ''Look to the Wilderness'', describes the expedition, the habitat, and the behavior of the dragon. The hall opened in 1927 and was rebuilt from 1969 to 1977 at a cost of $1.3 million.

Biodiversity and environmental halls

Hall of Biodiversity

The Hall of Biodiversity is underneath the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall.

It opened in May 1998. The hall primarily contains exhibits and objects highlighting the concept of

biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

, the interactions between living organisms, and the negative impacts of

extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

on biodiversity.

The hall includes a diorama depicting the

Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve rainforest with over 160 animal and plant species.

The diorama shows the rainforest in three states: pristine, altered by human activity, and destroyed by human activity.

Another attraction in the hall is "The Spectrum of Habitats", a

video wall displaying footage of nine ecosystems. There is a "Transformation Wall", containing information and stories detailing changes to biodiversity, and a "Solutions Wall", containing suggestions on how to increase biodiversity.

Hall of North American Forests

The Hall of North American Forests is a one-story hall on the museum's first floor in between the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall and the Warburg Hall of New York State Environments.

It contains ten dioramas depicting a range of forest types from across North America as well as several displays on forest conservation and tree health. The hall was constructed under the guidance of botanist Henry K. Svenson

and opened in 1958. Each diorama specifically lists both the location and exact time of year depicted.

Trees and plants featured in the dioramas are constructed of a combination of art supplies and actual bark and other specimens collected in the field. The entrance to the hall features a cross section from the

Mark Twain Tree, 1,400-year-old

sequoia taken from the King's River grove on the west flank of the

Sierra Mountains in 1891.

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments is a one-story hall on the museum's ground floor in between the Hall of North American Forests and the Grand Hall.

Based on the town of

Pine Plains in

Dutchess County, New York, the hall gives a multi-faceted presentation of the eco-systems typical of New York.

[ Aspects covered include soil types, seasonal changes, and the impact of both humans and nonhuman animals on the environment. It is named for the German-American philanthropist Felix M. Warburg and opened on May 14, 1951,]

Milstein Hall of Ocean Life

The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life is in the southeastern quadrant of the first floor, west of the Hall of Biodiversity.marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

and marine conservation. The center of the hall contains a -long blue whale model.mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

s, coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s, the bathypelagic, among others. It attempts to show how vast and varied the oceans are while encouraging common themes throughout.environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

and conservation being the main focal points, and was renamed after developer Paul Milstein and AMNH board member Irma Milstein. The 2003 renovation included refurbishment of the famous blue whale, suspended high above the exhibit floor; updates to the 1930s and 1960s dioramas; and electronic displays.[

]

Human origins and cultural halls

Cultural halls

Stout Hall of Asian Peoples

The Stout Hall of Asian Peoples is a one-story hall on the museum's second floor in between the Hall of Asian Mammals and Birds of the World.Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

, and Traditional Asia, a much larger section containing cultural artifacts from across the Asian continent. The latter section is organized to geographically correspond with two major trade routes of the Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

. Like many of the museum's exhibition halls, the artifacts in Stout Hall are presented in a variety of ways including exhibits, miniature dioramas, and five full-scale dioramas. Notable exhibits in the Ancient Eurasian section include reproductions from the archaeological sites of Teshik-Tash and Çatalhöyük, as well as a full size replica of a Hammurabi Stele. The Traditional Asia section contains areas devoted to major Asian countries, such as Japan, China, Tibet, and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, while also including a vast array of smaller Asian tribes including the Ainu, Semai, and Yakut.

File:Miniature of Isfahar.JPG, A forced perspective, miniature diorama of Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

File:Yakut Shaman Diorama.JPG, A Yakut shaman performs a healing rite in this diorama

File:Costumes of Islamic Women.JPG, A range of costumes worn by women in Islamic Asia

Hall of African Peoples

The Hall of African Peoples is behind Akeley Hall of African Mammals and underneath Sanford Hall of North American Birds.Desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

. Each section presents artifacts and exhibits of the peoples native to the ecosystems throughout Africa. The hall contains three dioramas and notable exhibits include a large collection of spiritual costumes on display in the Forest-Woodland section. Uniting the sections of the hall is a multi-faceted comparison of African societies based on hunting and gathering, cultivation, and animal domestication. Each type of society is presented in a historical, political, spiritual, and ecological context. A small section of African diaspora spread by the slave trade is also included.Ancient Egyptian

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

s, Nubians, Kuba, Lozi

*Grasslands: Pokot, Shilluk, Barawa

*Forest-Woodland: Yoruba, Kofyar, Mbuti

*Desert: Ait Atta, Tuareg

Hall of Mexico and Central America

The Hall of Mexico and Central America is a one-story hall on the museum's second floor behind Birds of the World and before the Hall of South American Peoples.

The Hall of Mexico and Central America is a one-story hall on the museum's second floor behind Birds of the World and before the Hall of South American Peoples.Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

, including the Maya, Olmec, Zapotec, and Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

. Because the great majority of the written records of these civilizations did not survive the Spanish conquest, the overarching aim of the hall is to piece together what it is possible to know about them from the artifacts alone.

The museum has displayed pre-Columbian artifacts since its opening, only a short time after the discovery of the civilizations by archaeologists, with its first hall dedicated to the subject opening in 1899. As the museum's collection grew, the hall underwent major renovations in 1944 and again in 1970 when it re-opened in its current form. Notable artifacts on display include the Kunz Axe and a full-scale replica of Tomb 104 from the Monte Albán

Monte Albán is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Municipality in the southern Mexico, Mexican state of Oaxaca (17.043° N, 96.767°W). The site is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain i ...

archaeological site, originally displayed at the 1939 World's Fair.

South American Peoples

The Hall of South American Peoples is a one-story hall on the northwestern corner of the second floor, next to the Hall of Mexico and Central America. The hall was first opened on the third floor in 1904, and exhibited archaeological objects, including mummies, from Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

, Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

, and the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. In 1931, the hall was expanded and relocated to the second floor under the direction of curators Ronald Olson and W.C. Bennett. The new hall included a recreation of a Chilean copper mine, and later, a temporary hall titled the Men of the Montaña, which featured Peruvian cultural artifacts from the Cashibo, and Panoan peoples.Inca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

.

Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples

The Hall of Pacific Peoples is on the southwestern corner of the third floor, accessed through the Hall of Plains Indians.

The Hall of Pacific Peoples is on the southwestern corner of the third floor, accessed through the Hall of Plains Indians. The Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples contains artifacts from

The Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples contains artifacts from New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

and other Pacific islands.New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

and other Pacific island locations, 1928–1939. Others, such as the theatrical set from a puppet play in Bali

Bali (English:; Balinese language, Balinese: ) is a Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller o ...

, were chosen from among the approximately 600 items that Mead and her anthropologist husband Gregory Bateson had sent to the American Museum of Natural History while they were conducting fieldwork in Bali, 1936–1938.moai

Moai or moʻai ( ; ; ) are monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui people on Easter Island, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in eastern Polynesia between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but h ...

'' statue and capes made of honeycreeper feathers.

Native American halls

=Northwest Coast Hall

=

The Northwest Coast Hall is a one-story hall on the museum's ground floor behind the Grand Gallery and in between Warburg and Spitzer Halls. Artifacts in the hall originated from three main sources. The earliest of these was a gift of Haida artifacts collected by John Wesley Powell and donated by future trustee Heber R. Bishop in 1882. This was followed by the museum's purchase of two collections of Tlingit artifacts collected by Lt. George T. Emmons in 1888 and 1894.

Artifacts in the hall originated from three main sources. The earliest of these was a gift of Haida artifacts collected by John Wesley Powell and donated by future trustee Heber R. Bishop in 1882. This was followed by the museum's purchase of two collections of Tlingit artifacts collected by Lt. George T. Emmons in 1888 and 1894.Nuu-chah-nulth

The Nuu-chah-nulth ( ; ), also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth or Tahkaht, are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada. The term Nuu-chah-nulth is used to describe fifteen related tri ...

, Tsimshian

The Tsimshian (; ) are an Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their communities are mostly in coastal British Columbia in Terrace, British Columbia, Terrace and ...

, and Nuxalk.

=Hall of Plains Indians

=

The Hall of Plains Indians is on the south side of the third floor, near the western end of the museum.Blackfoot Confederacy

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'', or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or "Blackfoot language, Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up ...

''), Hidatsa, and Dakota cultures. Of particular interest is a Folsom point discovered in 1926 New Mexico, providing evidence of early American colonization of the Americas.

=Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians

=

The Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians is next to the Hall of Plains Indians, on the south side of the third floor.Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

, Mohegan, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

, and Iroquois cultures. The exhibit features examples of indigenous basketry, pottery, farming techniques, food preparation, metal jewelry, musical instruments, and textiles. Other highlights include a model of a Menominee

The Menominee ( ; meaning ''"Menominee People"'', also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as ''Mamaceqtaw'', "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recognized tribe of Na ...

birchbark canoe and various traditional lodgings such as an Ojibwa domed wigwam, an Iroquois longhouse, a Creek council house, and other eastern woodland dwelling styles. , the Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians, along with the Hall of the Plains Indians, is closed to ensure compliance with new NAGPRA regulations.

Human origins halls

Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins

The Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins, formerly The Hall of Human Biology and Evolution, is on the south side of the first floor, near the western end of the museum.

The Anne and Bernard Spitzer Hall of Human Origins, formerly The Hall of Human Biology and Evolution, is on the south side of the first floor, near the western end of the museum.[ When it first opened in 1921, the hall was known as the "Hall of the Age of Man", the only major exhibition in the United States to present an in-depth investigation of human evolution.]Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

'', illuminated the path of human evolution and examined the origins of human creativity.Australopithecus afarensis

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would not ta ...

'', '' Homo ergaster'', Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

, and Cro-Magnon, showing each species demonstrating the behaviors and capabilities that scientists believe they were capable of. Also displayed are full-sized casts of important fossils, including the 3.2-million-year-old Lucy skeleton and the 1.7-million-year-old Turkana Boy, and ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' ( ) is an extinction, extinct species of Homo, archaic human from the Pleistocene, spanning nearly 2 million years. It is the first human species to evolve a humanlike body plan and human gait, gait, to early expansions of h ...

'' specimens including a cast of Peking Man.ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

art found in the Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; ) is a large rural departments of France, department in south west France, with its Prefectures in France, prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and ...

region of southwestern France. The limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

carvings of horses were made nearly 26,000 years ago and are considered to represent some of the earliest artistic expression of humans.

Earth and planetary science halls

Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites

The Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites is on the southwest corner of the first floor.Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, is one of the largest known iron meteorites, classified as a medium octahedrite in chemical group IIIAB meteorites, IIIAB. In addition to many small fragments, at least eight large ...

which was first made known to non-Inuit cultures on their investigation of Meteorite Island, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

. Its great weight, 34 tons, makes it the largest displayed in the Northern Hemisphere. It has support by columns that extend through the floor and into the bedrock below the museum.

The hall also contains extra-solar nanodiamonds (diamonds with dimensions on the nanometer level) more than 5 billion years old. These were extracted from a meteorite sample through chemical means, and they are so small that a quadrillion of these fit into a volume smaller than a cubic centimeter.

Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals

The Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals (formerly the Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Gems and Minerals) is on the first floor, north of the Ross Hall of Meteorites.plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

, and the stories of specific gems.

David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth

The David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth is on the first floor at the northeast corner of the museum.origin of life

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life arises from abiotic component, non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to organism, living entities on ...

and contemporary human impacts on the planet. The hall was designed to answer five key questions: "How has earth evolved? Why are there ocean basins, continents and mountains? How do scientists read rocks? What causes climate and climate change? Why is earth habitable?"geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

, glaciology

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or, more generally, ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clim ...

, atmospheric sciences, and volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geology, geological, geophysical and geochemistry, geochemical phenomena (volcanism). The term ''volcanology'' is derived from the Latin language, Latin ...

. The exhibit has several large, touchable rock specimens. The hall features striking samples of banded iron and deformed conglomerate rocks, as well as granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

s, sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s, lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

s, and three black smokers. The north section of the hall, which deals primarily with plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

, is arranged to mimic the Earth's structure, with the core and mantle at the center and crustal features on the perimeter.

Fossil halls

Storage facilities

Most of the museum's collections of mammalian and dinosaur fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s remain hidden from public view and are kept in many repositories deep within the museum complex.Whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

Bone Storage Room is a cavernous space in which powerful winches come down from the ceiling to move the giant fossil bones about. The museum attic upstairs includes even more storage facilities, such as the Elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

Room, while the tusk vault and boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

vault are downstairs from the attic.

Public displays

The great fossil collections that are open to public view occupy the entire fourth floor of the museum.[ On the 77th Street side of the museum the visitor begins in the Orientation Center and follows a carefully marked path, which takes the visitor along an evolutionary ]tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythology, mythological, religion, religious, and philosophy, philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The ...

. As the tree "branches" the visitor is presented with the familial relationships among vertebrates, called cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

s. A video projection on the museum's fourth floor introduces visitors to the concept of the cladogram.[

Many of the fossils on display represent unique and historic pieces that were collected during the museum's golden era of worldwide expeditions (1880s–1930s).]Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, South America, and central and eastern Africa.

Halls

The first dinosaur hall in the museum opened in 1905.

Fossils on display

The fossils on display include:

*'' Tyrannosaurus rex'': Composed almost entirely of real fossil bones, it is mounted in a horizontal stalking pose balanced on powerful legs. The specimen is actually composed of fossil bones from two ''T. rex'' skeletons discovered in

The fossils on display include:

*'' Tyrannosaurus rex'': Composed almost entirely of real fossil bones, it is mounted in a horizontal stalking pose balanced on powerful legs. The specimen is actually composed of fossil bones from two ''T. rex'' skeletons discovered in Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

in 1902 and 1908 by famous dinosaur hunter Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. He discovered the first documented remains of ''Tyrannosaurus'' during a career that made him one of the most famous fossil ...

.

*'' Mammuthus'': Larger than its relative the woolly mammoth, these fossils are from an animal that lived 11,000 years ago in Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

.

*'' Apatosaurus'' or '' Brontosaurus'': This giant specimen was discovered at the end of the 19th century. Although most of its fossil bones are original, the skull is not, since none was found on site. The skeleton is composed primarily of the specimen AMNH 460, as well as specimens AMNH 222, AMNH 339, AMNH 592, and casts of the ''Brontosaurus excelsus'' holotype YPM 1980.[Tschopp, E., Mateus, O., & Benson, R. B. (2015). A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). ''PeerJ'', ''3'', e857.] It was only many years later that the first ''Apatosaurus'' skull was discovered, and so a plaster cast of that skull was made and placed on the museum's mount. A '' Camarasaurus'' skull had been used mistakenly until a correct skull was found. It is not entirely certain whether this specimen is a ''Brontosaurus'' or an ''Apatosaurus'', and therefore it is considered an "unidentified apatosaurine", as it could also potentially be its own genus and species.horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

and rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

. It lived 35 million years ago in what is now South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

. It is noted for its magnificent and unusual pair of horns.

*A skeleton of '' Edmontosaurus annectens'', a large herbivorous ornithopod dinosaur. The specimen is an example of a "mummified" dinosaur fossil in which the soft tissue and skin impressions were imbedded in the surrounding rock. The specimen is mounted as it was found, lying on its side with its legs drawn up and head drawn backwards.

*On September 26, 2007, an 80-million-year-old, diameter fossil of an ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

, which is composed entirely of the gemstone ammolite, made its debut at the museum. Neil Landman, curator of fossil invertebrates

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordate subphylum ...

, explained that ammonites (shelled cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s in the subclass Ammonoidea) became extinct 66 million years ago, in the same extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

that killed the dinosaurs. Korite International donated the fossil after its discovery in Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, Canada.Triceratops

''Triceratops'' ( ; ) is a genus of Chasmosaurinae, chasmosaurine Ceratopsia, ceratopsian dinosaur that lived during the late Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 68 to 66 million years ago on the island ...

'' and a '' Stegosaurus'' are also both on display, among many other specimens.

Besides the fossils in museum display, many specimens are stored in the collections available for scientists. Those include important specimens such as complete diplodocid skull, tyrannosaurid teeth, sauropod vertebrae, and many holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

s.

Rose Center for Earth and Space

The Hayden Planetarium, connected to the museum, is now part of the Rose Center for Earth and Space on the north side of the museum.

The Hayden Planetarium, connected to the museum, is now part of the Rose Center for Earth and Space on the north side of the museum.

Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation

Designed by Studio Gang and landscape architects Reed Hilderbrand, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education and Innovation opened in May 2023. The 230,000-square-foot addition includes six floors above ground, and one below. The Gilder Center welcomes visitors with a new, accessible entrance on Columbus Avenue that connects to central five-story atrium and creates more than 30 connections to the existing museum. The atrium's architecture is informed by natural processes like the movement of wind and water that shape geological landscapes. To achieve the continuous visual form, the atrium is constructed with shotcrete. The curvilinear façade contrasts with the earlier High Victorian Gothic, Richardson Romanesque, and Beaux Arts structures, but its Milford Pink granite cladding is the same stone used on the Museum's west side. This expansion was originally supposed to be north of the existing museum, occupying parts of Theodore Roosevelt Park. The expansion was relocated to the west side of the existing museum, and its footprint was reduced in size, due to opposition to construction in the park. The annex replaced three existing buildings along Columbus Avenue's east side.

This expansion was originally supposed to be north of the existing museum, occupying parts of Theodore Roosevelt Park. The expansion was relocated to the west side of the existing museum, and its footprint was reduced in size, due to opposition to construction in the park. The annex replaced three existing buildings along Columbus Avenue's east side.

Exhibitions Lab

Founded in 1869, the AMNH Exhibitions Lab has since produced thousands of installations. The department is notable for its integration of new scientific research into immersive art and multimedia presentations. In addition to the famous dioramas at its home museum and the Rose Center for Earth and Space, the lab has also produced international exhibitions and software such as the Digital Universe Atlas.