Presidential elections

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The ...

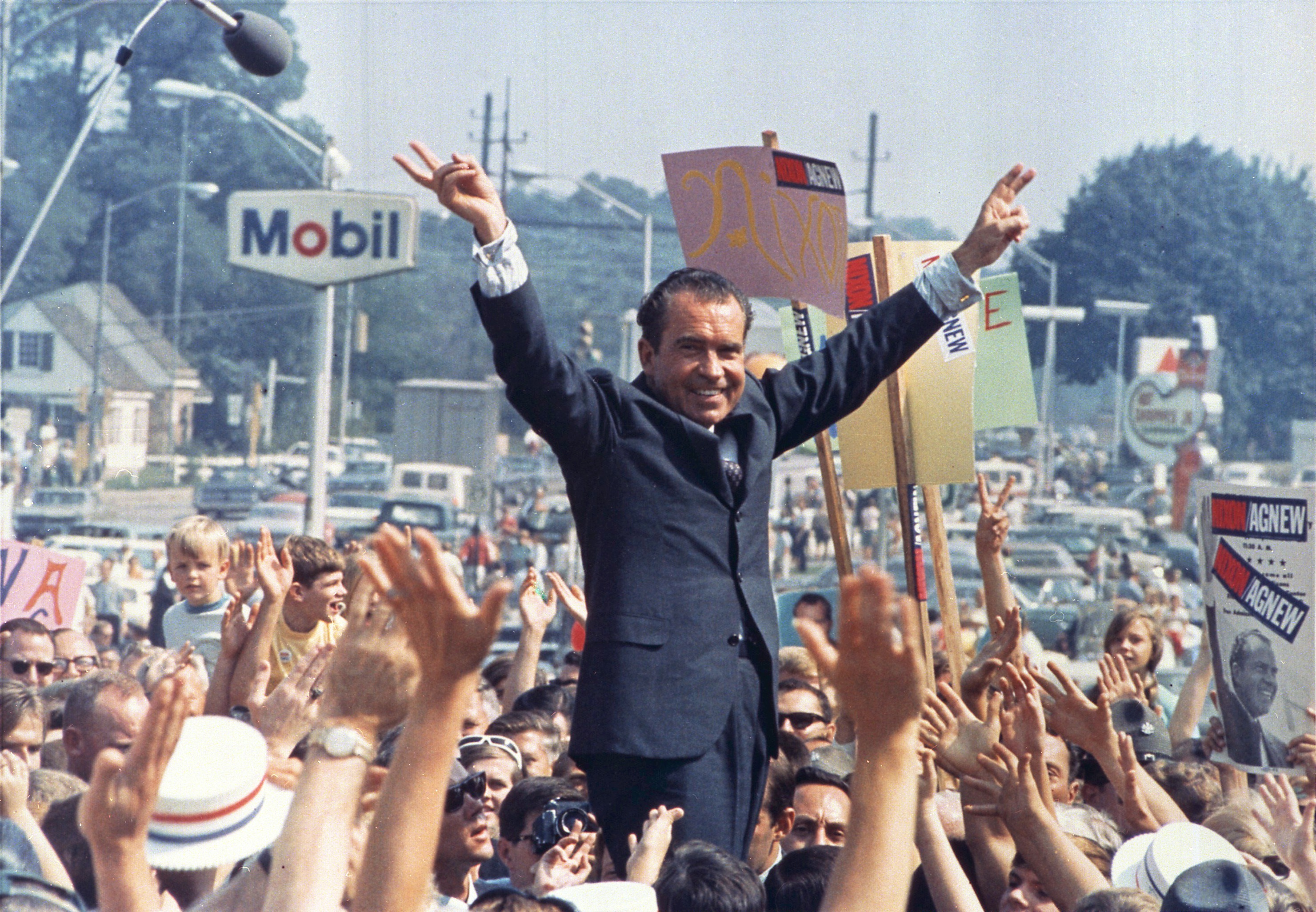

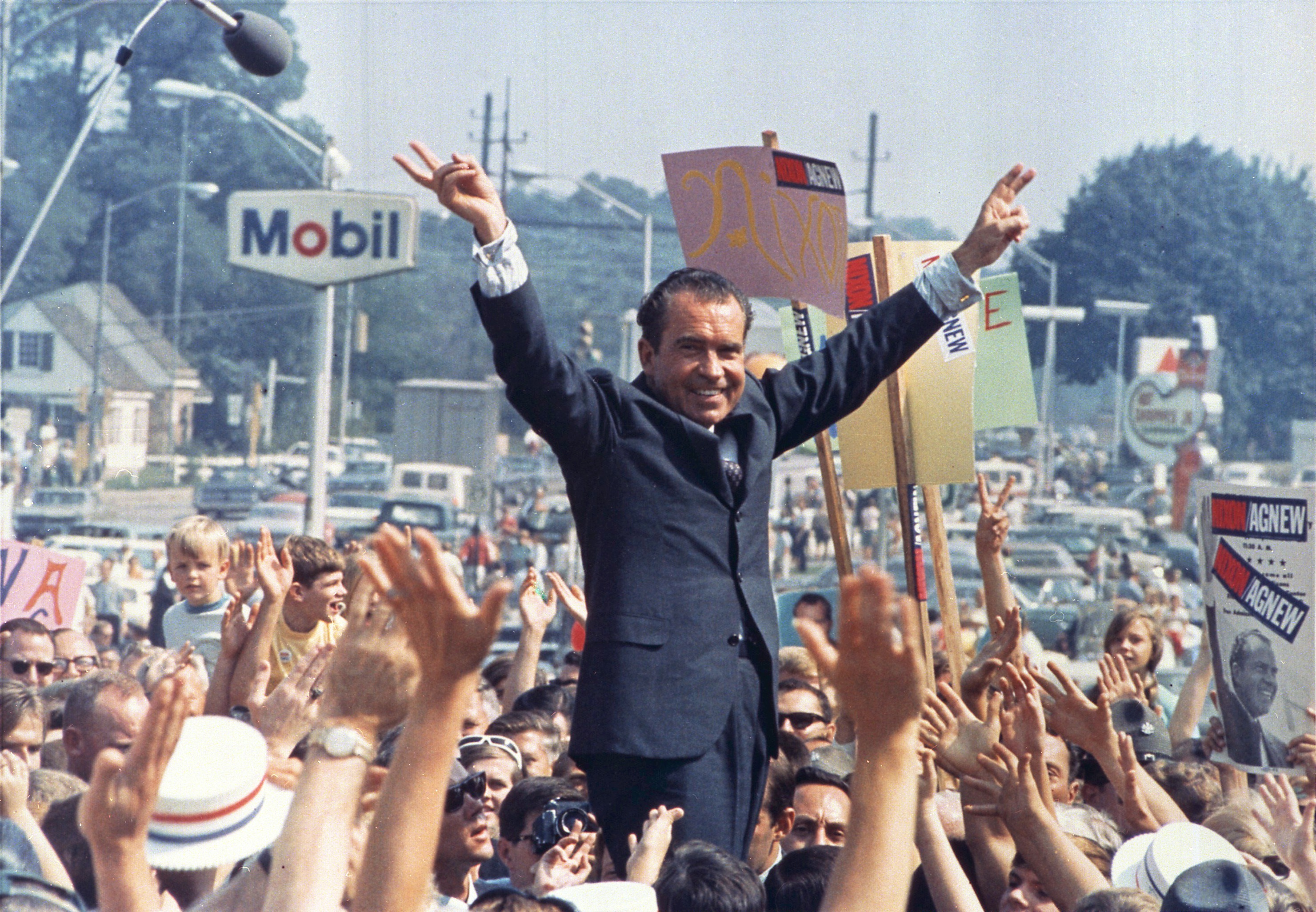

were held in the United States on November 5, 1968. The

Republican ticket of former vice president

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and Maryland governor

Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

, defeated both the

Democratic ticket of incumbent vice president

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

and senator

Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1 ...

, and the

American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is an American political party that was established in 1967. The American Independent Party is best known for its nomination of Democratic then-former Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five s ...

ticket of former Alabama governor

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

and general

Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was a United States Air Force, US Air Force General (United States), general who was a key American military commander during the Cold War. He served as Chief of Staff of the United St ...

. It is often considered a major

realigning election

A political realignment is a set of sharp changes in party-related ideology, issues, leaders, regional bases, demographic bases, and/or the structure of powers within a government. In the fields of political science and political history, this is ...

, as it permanently disrupted the Democratic

New Deal Coalition

The New Deal coalition was an American political coalition that supported the Democratic Party beginning in 1932. The coalition is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, and the follow-up Democratic presidents. It was ...

that had dominated presidential politics since

1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

.

Incumbent president

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

had been the early frontrunner for the Democratic Party's nomination but

withdrew from the race after only narrowly winning the

New Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest, the first being the Iowa caucuses, held in the United States every four years as part of the process of cho ...

. Humphrey,

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

, and

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 – June 6, 1968), also known as RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New Yo ...

emerged as the three major candidates in the

Democratic primaries until Kennedy was assassinated in June 1968, part of a streak of high-profile assassinations in the 1960s. Humphrey edged out anti-Vietnam war candidate McCarthy to win the Democratic nomination, sparking numerous anti-war protests. Nixon, who lost in

1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

to

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, entered the

Republican primaries as the front-runner, defeating liberal New York governor

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

, conservative California governor

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, and other candidates to win his party's nomination.

The election year was tumultuous and chaotic. It was marked by the

assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an American civil rights activist, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:05& ...

in early April, and the subsequent

54 days of riots across the nation; the

assassination of Robert F. Kennedy

On June 5, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was shot by Sirhan Sirhan at the Ambassador Hotel (Los Angeles), Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California, and pronounced dead the following day.

Kennedy, a United States senator and candidate in the 19 ...

in early June; and widespread

opposition to the Vietnam War

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1965 with demonstrations against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War, United States in the war. Over the next several years, these demonstrations grew ...

across university campuses as well as

at the Democratic National Convention, which saw widely publicized police crackdowns on protesters, reporters, and bystanders.

Humphrey's promise to continue the Johnson administration's

war on poverty and support for the

civil rights movement led to an erosion of Democratic support in the South. This prompted a run by Wallace on the ticket of the newly-formed

American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is an American political party that was established in 1967. The American Independent Party is best known for its nomination of Democratic then-former Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five s ...

, which campaigned in favor of

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

on the basis of "

states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

." Wallace attracted

socially conservative

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional social structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institu ...

voters throughout the South (including

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

as well as former

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

supporters who preferred Wallace over Nixon), and drew further support from white working-class voters in the Industrial North and Midwest who were attracted to his economic populism and anti-establishment rhetoric.

Nixon, promising to restore

law and order to the nation's cities and provide new leadership in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, aimed at attracting a "

silent majority

The silent majority is an unspecified large group of people in a country or group who do not express their opinions publicly. The term was popularized by U.S. President Richard Nixon in a televised address on November 3, 1969, in which he said, "A ...

" of moderate voters who were alienated by both Humphrey's

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

agenda and Wallace's

ultraconservative

Ultraconservatism refers to extreme conservative views in politics or religious practice. In modern politics, ''ultraconservative'' usually refers to conservatives of the far-right on the political spectrum, comprising groups or individuals wh ...

viewpoints; Nixon also pursued a "

southern strategy" and employed coded language in the Upper South, where the electorate was less extreme on the segregation issue.

Humphrey trailed Nixon by wide margins in polls taken during most of the campaign from late August to early October. In the final month of the campaign, Humphrey managed to narrow Nixon's lead after Wallace's candidacy collapsed and Johnson suspended

bombing in the Vietnam War to appease the

anti-war movement

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during con ...

; the election was considered a tossup by election day. Nixon managed to secure a close victory in the

popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the tota ...

, with just over 500,000 votes (0.7%) separating him and Humphrey. In the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, Nixon's victory was larger; he carried the tipping point state of

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

by over 90,000 votes (2.3%), and his overall margin of victory in the Electoral College was 110 votes. Wallace became the most recent third-party candidate (as of 2024) to carry any state in a presidential election. This was the first presidential election after the passage of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

, which began restoring voting rights to Black Americans in the South, who had been

disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also disenfranchisement (which has become more common since 1982) or voter disqualification, is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing someo ...

for decades under

Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

.

This was the last presidential election until

2024

The year saw the list of ongoing armed conflicts, continuation of major armed conflicts, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Myanmar civil war (2021–present), Myanmar civil war, the Sudanese civil war (2023–present), Sudane ...

in which the incumbent president was eligible to run again but was not the eventual nominee of their party. Nixon also became the first non-incumbent vice president to be elected president, something that would not happen again until

2020

The year 2020 was heavily defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to global Social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, social and Economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic disruption, mass cancellations and postponements of even ...

.

Background

In the

1964 U.S. presidential election, incumbent

Democratic President

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

won the largest popular vote landslide in

U.S. presidential election

The election of the president and vice president of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are registered to vote in one of the fifty U.S. states or in Washington, D.C., cast ballots not directl ...

history over

Republican Senator

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

. During the presidential term that followed, Johnson was able to achieve many political successes, including passage of his

Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

domestic programs (including "

War on Poverty" legislation), landmark

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

legislation, and the continued exploration of space. Despite these significant achievements, Johnson's popular support would be short-lived. Even as Johnson scored legislative victories, the country endured large-scale race riots in the streets of its larger cities, along with a generational revolt of young people and violent debates over foreign policy. The emergence of the

hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture of the mid-1960s to early 1970s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States and spread to dif ...

counter-culture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Ho ...

, the rise of

New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

activism, and the emergence of the

Black Power

Black power is a list of political slogans, political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used in the United States b ...

movement exacerbated social and cultural clashes between classes, generations, and races. Adding to the national crisis, on April 4, 1968,

civil rights movement leader

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

was

assassinated

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

in

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, igniting

riots

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

of grief and anger across the country. In

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, rioting took place within a few blocks of the White House, and the government stationed soldiers with machine guns on the Capitol steps to protect it.

The

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

was the primary reason for the precipitous decline of President Johnson's popularity. He had escalated U.S. commitment so by late 1967 over 500,000 American soldiers were fighting in Vietnam. Draftees made up 42 percent of the military in Vietnam, but suffered 58% of the casualties, as nearly 1000 Americans a month were killed, and many more were injured. Resistance to the war rose as success seemed ever out of reach. The national

news media

The news media or news industry are forms of mass media that focus on delivering news to the general public. These include News agency, news agencies, newspapers, news magazines, News broadcasting, news channels etc.

History

Some of the fir ...

began to focus on the high costs and ambiguous results of escalation, despite Johnson's repeated efforts to downplay the seriousness of the situation. In early January 1968,

Secretary of Defense

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divided ...

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

said the war would be winding down, claiming that the North Vietnamese were losing their will to fight. Shortly thereafter, the North Vietnamese launched the

Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. The Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) launched a surprise attack on 30 January 1968 against the forces of ...

, in which they and Communist forces of

Vietcong

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the Communism, communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vi ...

undertook simultaneous attacks on all government strongholds across South Vietnam. Although the uprising ended in a U.S. military victory, the scale of the Tet offensive led many Americans to question whether the war could be won, or was worth the costs to the United States. In addition, voters began to mistrust the government's assessment and reporting of the war effort. The Pentagon called for sending several hundred thousand more soldiers to Vietnam, while Johnson's approval ratings fell below 35%. The

Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For i ...

refused to let the president visit American colleges and universities, and prevented him from appearing at the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

in

Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, because it could not guarantee his safety.

Republican Party nomination

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their flying home delegation in the case of

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term referring to a presidential candidate, either one that is nominated by a state but considered a nonviable candidate or a politician whose electoral appeal derives from their native state, r ...

s.

Nixon received 1,679,443 votes in the primaries.

Primaries

The

front-runner

In politics, a front-runner (also spelled frontrunner or front runner) is a leader in an electoral race. While the front-runner in athletic events (the namesake of the political concept) is generally clear, a political front-runner, particularly i ...

for the Republican nomination was former Vice President Richard Nixon, who formally began campaigning in January 1968.

Nixon had worked behind the scenes and was instrumental in Republican gains in Congress and governorships in the 1966 midterm elections. Thus, the party machinery and many of the new congressmen and governors supported him. Still, there was caution in the Republican ranks over Nixon, who had lost the

1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

election to

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

and then lost the

1962 California gubernatorial election

Year 196 (Roman numerals, CXCVI) was a leap year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Dexter and Messalla (or, less frequently, year 949 ''Ab urbe condita''). The denomination 1 ...

. Some hoped a more "electable" candidate would emerge. The story of the 1968 Republican primary campaign and nomination may be seen as one Nixon opponent after another entering the race and then dropping out. Nixon was the front runner throughout the contest because of his superior organization, and he easily defeated the rest of the field.

Nixon's first challenger was Michigan Governor

George W. Romney

George Wilcken Romney (July 8, 1907 – July 26, 1995) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as chairman and president of American Motors Corporation from 1954 to 1962, the 43rd gove ...

. A Gallup poll in mid-1967 showed Nixon with 39%, followed by Romney with 25%. After a fact-finding trip to Vietnam, Romney told Detroit talk show host

Lou Gordon that he had been "brainwashed" by the military and the diplomatic corps into supporting the Vietnam War; the remark led to weeks of ridicule in the national news media. Turning against American involvement in Vietnam, Romney planned to run as the anti-war Republican version of

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

. Following his "

brainwashing

Brainwashing is the controversial idea that the human mind can be altered or controlled against a person's will by manipulative psychological techniques. Brainwashing is said to reduce its subject's ability to think critically or independently ...

" comment, Romney's support faded steadily; with polls showing him far behind Nixon, he withdrew from the race on February 28, 1968. Senator

Charles Percy was considered another potential threat to Nixon, and had planned on waging an active campaign after securing a role as Illinois's favorite son. Later, however, Percy declined to have his name listed on the ballot for the Illinois presidential primary, as he no longer sought the presidential nomination.

Nixon won a resounding victory in the important New Hampshire primary on March 12, with 78% of the vote. Anti-war Republicans wrote in the name of New York governor

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

, the ''de facto'' leader of the

Republican Party's liberal wing, who received 11% of the vote and became Nixon's new challenger. Rockefeller had not originally intended to run, having discounted a campaign for the nomination in 1965, and planned to make U.S. Senator

Jacob Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. During his time in politics, he served in both chambers of the United States Congress, a member of the United States House of Representa ...

, the

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term referring to a presidential candidate, either one that is nominated by a state but considered a nonviable candidate or a politician whose electoral appeal derives from their native state, r ...

, either in preparation of a presidential campaign or to secure him the second spot on the ticket. As Rockefeller warmed to the idea of entering the race, Javits shifted his effort to seeking a third term in the Senate. Nixon led Rockefeller in the polls throughout the primary campaign—though Rockefeller defeated Nixon and

Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

John Volpe

John Anthony Volpe ( ; December 8, 1908November 11, 1994) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician from Massachusetts. A son of Italian immigrants, he founded and owned a large construction firm. Politically, he was a Republican in ...

in the

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

primary on April 30, he otherwise fared poorly in state primaries and conventions. He had declared too late to get his name placed on state primary ballots.

By early spring, California Governor

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, a leader of the Republican Party's conservative wing, had become Nixon's chief rival. In the Nebraska primary on May 14, Nixon won with 70% of the vote to 21% for Reagan and 5% for Rockefeller. While this was a wide margin for Nixon, Reagan remained Nixon's leading challenger. Nixon won the next primary of importance, Oregon, on May 15 with 65% of the vote, and won all the following primaries except for California (June 4), where only Reagan appeared on the ballot. Reagan's victory in California gave him a plurality of the nationwide primary vote, but his poor showing in most other state primaries left him far behind Nixon in the delegate count.

Total popular vote:

*

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

: 1,696,632 (37.93%)

*

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

: 1,679,443 (37.54%)

*

James A. Rhodes

James Allen Rhodes (September 13, 1909 – March 4, 2001) was an American attorney and Republican politician who served as the 61st and 63rd Governor of Ohio from 1963 to 1971 and from 1975 to 1983. Rhodes was one of only seven U.S. governors ...

: 614,492 (13.74%)

*

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

: 164,340 (3.67%)

* Unpledged: 140,639 (3.14%)

*

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

(write-in): 44,520 (1.00%)

*

Harold Stassen

Harold Edward Stassen (April 13, 1907 – March 4, 2001) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician, military officer, and attorney who was the List of governors of Minnesota, 25th governor of Minnesota from 193 ...

: 31,655 (0.71%)

*

John Volpe

John Anthony Volpe ( ; December 8, 1908November 11, 1994) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician from Massachusetts. A son of Italian immigrants, he founded and owned a large construction firm. Politically, he was a Republican in ...

: 31,465 (0.70%)

* Others: 21,456 (0.51%)

*

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

(write-in): 15,291 (0.34%)

*

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 – June 6, 1968), also known as RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New Yo ...

(write-in): 14,524 (0.33%)

*

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

(write-in): 5,698 (0.13)

*

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

(write-in): 4,824 (0.11%)

*

George W. Romney

George Wilcken Romney (July 8, 1907 – July 26, 1995) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as chairman and president of American Motors Corporation from 1954 to 1962, the 43rd gove ...

: 4,447 (0.10%)

*

Raymond P. Shafer

Raymond Philip Shafer (March 5, 1917 – December 12, 2006) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 39th governor of Pennsylvania from 1967 to 1971. Prior to that, he served as the 23rd lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania from ...

: 1,223 (0.03%)

*

William Scranton

William Warren Scranton (July 19, 1917 – July 28, 2013) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician and diplomat. Scranton served as the 38th governor of Pennsylvania from 1963 to 1967, and as United States Am ...

: 724 (0.02%)

*

Charles H. Percy

Charles Harting Percy (September 27, 1919 – September 17, 2011), also known as Chuck Percy, was an American businessman and politician. He was president of the Bell & Howell Corporation from 1949 to 1964, and served as a Republican U.S. sen ...

: 689 (0.02%)

*

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

: 598 (0.01%)

*

John Lindsay

John Vliet Lindsay (; November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician and lawyer. During his political career, Lindsay was a U.S. congressman, the mayor of New York City, and a candidate for U.S. president. He was also a regu ...

: 591 (0.01%)

Republican Convention

As the 1968 Republican National Convention opened on August 5 in

Miami Beach, Florida

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. It is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida. The municipality is located on natural and human-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, the

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

estimated that Nixon had 656 delegate votes – 11 short of the number he needed to win the nomination. Reagan and Rockefeller were his only remaining opponents and they planned to unite their forces in a "stop-Nixon" movement. Because Goldwater had done well in the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, delegates to the

1968 Republican National Convention

The 1968 Republican National Convention was held at the Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Dade County, Florida, USA, from August 5 to August 8, 1968, to select the party's nominee in the general election. It nominated former Vice P ...

included more Southern conservatives than in past conventions. There seemed potential for the conservative Reagan to be nominated if no victor emerged on the first ballot. Nixon narrowly secured the nomination on the first ballot, with the aid of South Carolina Senator

Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902 – June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Before his 49 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South ...

, who had switched parties in 1964. He selected

dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person, team or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, that is unlikely to succeed but has a fighting chance, unlike the underdog who is exp ...

Maryland Governor

Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party, appealing to both Northern moderates and Southerners disaffected with the Democrats. Nixon's first choice for running mate was reportedly his longtime friend and ally

Robert Finch, who was the

Lieutenant Governor of California

The lieutenant governor of California is the second highest Executive (government), executive officer of the government of the U.S. state of California. The Lieutenant governor (United States), lieutenant governor is elected to serve a four-yea ...

at the time. Finch declined that offer, but later accepted an appointment as the

Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare

The United States secretary of health and human services is the head of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, and serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all health matters. The secretary is ...

in Nixon's administration. With Vietnam a key issue, Nixon had strongly considered tapping his 1960 running mate,

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (July 5, 1902 – February 27, 1985) was an American diplomat and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate and served as United States Ambassador to the United Nations in the administration of Pre ...

, a former U.S. senator, ambassador to the UN, and ambassador twice to

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

.

As of the 2020 presidential election, 1968 was the last time that two siblings (Nelson and Winthrop Rockefeller) ran against each other in a

presidential primary.

Democratic Party nomination

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their home delegation in the case of

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term referring to a presidential candidate, either one that is nominated by a state but considered a nonviable candidate or a politician whose electoral appeal derives from their native state, r ...

s. Humphrey received 166,463 votes in the primaries.

Enter Eugene McCarthy

Because Lyndon B. Johnson had been elected to the presidency only once, in 1964, and had served less than two full years of the term before that, the

Twenty-second Amendment

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution limits the number of times a person can be elected to the office of President of the United States to two terms, and sets additional eligibility conditions for presi ...

did not disqualify him from running for another term. As a result, it was widely assumed when 1968 began that President Johnson would run for another term, and that he would have little trouble winning the Democratic nomination.

Despite growing opposition to Johnson's policies in Vietnam, it appeared that no prominent Democratic candidate would run against a sitting president of his own party. It was also accepted at the beginning of the year that Johnson's record of domestic accomplishments would overshadow public opposition to the Vietnam War and that he would easily boost his public image after he started campaigning.

Even Senator

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 – June 6, 1968), also known as RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New Yo ...

from New York, an outspoken critic of Johnson's policies, with a large base of support, publicly declined to run against Johnson in the primaries. Poll numbers also suggested that a large share of Americans who opposed the Vietnam War felt the growth of the anti-war

hippie movement

The hippie subculture (also known as the flower people) began its development as a teenager and youth movement in the United States from the mid-1960s to early 1970s and then developed around the world.

Its origins may be traced to European soc ...

among younger Americans and violent unrest on college campuses

was not helping their cause.

On January 30, however, claims by the Johnson administration that a recent troop surge would soon bring an end to the war were severely discredited when the

Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. The Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) launched a surprise attack on 30 January 1968 against the forces of ...

broke out. Although the American military was eventually able to fend off the attacks, and also inflict heavy losses among the communist opposition, the ability of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong to launch large scale attacks during the Tet Offensive's long duration greatly weakened American support for the military draft and further combat operations in Vietnam.

A recorded phone conversation which Johnson had with Chicago mayor

Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the mayor of Chicago from 1955, and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party from 1953, until his death. He has been called "the last of ...

on January 27 revealed that both men had become aware of Kennedy's private intention to enter the Democratic presidential primaries and that Johnson was willing to accept Daley's offer to run as Humphrey's vice presidential running mate if he were to end his re-election campaign.

Daley, whose city would host the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

, also preferred either Johnson or Humphrey over any other candidate, and stated that Kennedy had met him the week before, and that he was unsuccessful in his attempt to win over Daley's support.

In time, only Senator

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

from Minnesota proved willing to challenge Johnson openly. Running as an anti-war candidate in the

New Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest, the first being the Iowa caucuses, held in the United States every four years as part of the process of cho ...

, McCarthy hoped to pressure the Democrats into publicly opposing the Vietnam War. Since New Hampshire was the first presidential primary of 1968, McCarthy poured most of his limited resources into the state. He was boosted by thousands of young college students, led by youth coordinator

Sam Brown, who shaved their beards and cut their hair to be "Clean for Gene". These students organized get-out-the-vote drives, rang doorbells, distributed McCarthy buttons and leaflets, and worked hard in New Hampshire for McCarthy. On March 12, McCarthy won 42 percent of the primary vote, to Johnson's 49 percent, a shockingly strong showing against an incumbent president, which was even more impressive because Johnson had more than 24 supporters running for the Democratic National Convention delegate slots to be filled in the election, while McCarthy's campaign organized more strategically. McCarthy won 20 of the 24 delegates. This gave McCarthy's campaign legitimacy and momentum. Sensing Johnson's vulnerability, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced his candidacy four days after the New Hampshire primary on March 16. Thereafter, McCarthy and Kennedy engaged in a series of state primaries.

Johnson withdraws

On March 31, 1968, following the New Hampshire primary and Kennedy's entry into the election, the president made a televised speech to the nation and said that he was suspending all bombing of North Vietnam in favor of peace talks. After concluding his speech, Johnson announced,

"With America's sons in the fields far away, with America's future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world's hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties, other than the awesome duties of this office — the presidency of your country. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President."

Not discussed publicly at the time was Johnson's concern that he might not survive another term – Johnson's health was poor, and he had already suffered a serious

heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

in 1955. He died on January 22, 1973, two days after the end of the new presidential term. Bleak political forecasts also contributed to Johnson's withdrawal; internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin, the next state to hold a primary election, showed him trailing badly. This was the second and until

Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

's

withdrawal from the

2024 race most recent time an incumbent US president eligible to run withdrew from the presidential election.

Historians have debated why Johnson quit a few days after his weak showing in New Hampshire.

Jeff Shesol says Johnson wanted out of the White House, but also wanted vindication; when the indicators turned negative, he decided to leave. Lewis L. Gould says that Johnson had neglected the Democratic party, was hurting it by his Vietnam policies, and under-estimated McCarthy's strength until the last minute, when it was too late for Johnson to recover. Randall Bennett Woods said Johnson realized he needed to leave, for the nation to heal.

Robert Dallek

Robert A. Dallek (born May 16, 1934) is an American historian specializing in the presidents of the United States, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon.

In 2004, he retired as a history profes ...

writes that Johnson had no further domestic goals, and realized that his personality had eroded his popularity. His health was poor, and he was pre-occupied with the Kennedy campaign; his wife was pressing for his retirement, and his base of support continued to shrink. Leaving the race would allow him to pose as a peace-maker. Anthony J. Bennett, however, said Johnson "had been forced out of a re-election race in 1968 by outrage over his policy in Southeast Asia".

In 2009, an AP reporter said that Johnson decided to end his re-election bid after CBS News anchor

Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 – July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' from 1962 to 1981. During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the most trust ...

, who was influential, turned against the president's policy in Vietnam. During a CBS News editorial which aired on February 27, Cronkite recommended the US pursue peace negotiations.

After watching Cronkite's editorial, Johnson allegedly exclaimed: "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America."

This quote by Johnson has been disputed for accuracy.

Johnson was attending Texas Governor John Connally's birthday gala in Austin, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired and did not see the original broadcast.

But, Cronkite and CBS News correspondent

Bob Schieffer

Bob Lloyd Schieffer (born February 25, 1937) is an American television journalist. He is known for his moderation of presidential debates, where he has been praised for his capability. Schieffer is one of the few journalists to have covered all f ...

defended reports that the remark had been made. They said that members of Johnson's inner circle, who had watched the editorial with the president, including presidential aide

George Christian and journalist

Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers (born Billy Don Moyers; June 5, 1934) is an American journalist and political commentator. Under the Johnson administration he served from 1965 to 1967 as the eleventh White House Press Secretary. He was a director of the Council ...

, later confirmed the accuracy of the quote to them.

Schieffer, who was a reporter for the ''

Star-Telegram

The ''Fort Worth Star-Telegram'' is an American daily newspaper serving Fort Worth, Texas, Fort Worth and Tarrant County, the western half of the North Texas area known as the Dallas Fort Worth Metroplex, Metroplex. It is owned by The McClatchy ...

s

WBAP television station in Fort Worth, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired, acknowledged reports that the president saw the editorial's original broadcast were inaccurate,

but claimed the president was able to watch a taping of it the morning after it aired and then made the remark.

However, Johnson's January 27, 1968, phone conversion with Chicago Mayor

Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the mayor of Chicago from 1955, and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party from 1953, until his death. He has been called "the last of ...

revealed that the two were trying to feed Robert Kennedy's ego so he would stay in the race, convincing him that the Democratic Party was undergoing a "revolution".

They suggested he might earn a spot as vice president.

After Johnson's withdrawal, the Democratic Party quickly split into four factions.

* The first faction consisted of labor unions and big-city party bosses (led by Chicago mayor

Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the mayor of Chicago from 1955, and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party from 1953, until his death. He has been called "the last of ...

). This group had traditionally controlled the Democratic Party since the days of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, and they feared loss of their control over the party. After Johnson's withdrawal, this group rallied to support Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's Vice President; it was also believed that Johnson himself was covertly supporting Humphrey, despite his public claims of neutrality.

* The second faction, which rallied behind Senator Eugene McCarthy, was composed of college students, intellectuals, and upper-middle-class urban whites who had been the early activists against the war in Vietnam; they perceived themselves as the future of the Democratic Party.

* The third group was primarily composed of African Americans and Hispanic Americans, as well as some anti-war groups; these groups rallied behind Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

* The fourth group consisted of white Southern Democrats. Some older voters, remembering the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

's positive impact upon the rural South, supported Vice President Humphrey. Many would rally behind the third-party campaign of former Alabama Governor

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

as a "law and order" candidate.

Since the Vietnam War had become the major issue that was dividing the Democratic Party, and Johnson had come to symbolize the war for many liberal Democrats, Johnson believed that he could not win the nomination without a major struggle, and that he would probably lose the election in November to the Republicans. However, by withdrawing from the race, he could avoid the stigma of defeat, and he could keep control of the party machinery by giving the nomination to Humphrey, who had been a loyal vice president. Milne (2011) argues that, in terms of foreign-policy in the Vietnam War, Johnson at the end wanted Nixon to be president rather than Humphrey, since Johnson agreed with Nixon, rather than Humphrey, on the need to defend South Vietnam from communism. However, Johnson's telephone calls show that Johnson believed the Nixon camp was deliberately sabotaging the

Paris peace talks

The Paris Peace Accords (), officially the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam (), was a peace agreement signed on January 27, 1973, to establish peace in Vietnam and end the Vietnam War. It took effect at 8:00 the follow ...

. He told Humphrey, who refused to use allegations based on illegal wiretaps of a presidential candidate. Nixon himself called Johnson and denied the allegations. Dallek concludes that Nixon's advice to Saigon made no difference, and that Humphrey was so closely identified with Johnson's unpopular policies that no last-minute deal with Hanoi could have affected the election.

Contest

After Johnson's withdrawal,

Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Hubert Humphrey announced his candidacy. Kennedy was successful in four state primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California), and McCarthy won six (Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Oregon, New Jersey, and Illinois). However, in primaries where they campaigned directly against one another, Kennedy won four primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California), and McCarthy won only one (Oregon). Humphrey did not compete in the primaries, leaving that job to

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term referring to a presidential candidate, either one that is nominated by a state but considered a nonviable candidate or a politician whose electoral appeal derives from their native state, r ...

s who were his surrogates, notably

United States Senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

George A. Smathers

George Armistead Smathers (November 14, 1913 – January 20, 2007) was an American lawyer and politician from the state of Florida who served in both chambers of the United States Congress, the United States House of Representatives from 1947 t ...

from

Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

,

United States Senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

Stephen M. Young from

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, and

Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Roger D. Branigin

Roger Douglas Branigin (July 26, 1902 – November 19, 1975) was an American politician who was the 42nd governor of Indiana, serving from January 11, 1965, to January 13, 1969. A World War II veteran and well-known public speaker, Branigin t ...

of

Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. Instead, Humphrey concentrated on winning the delegates in non-primary states, where party leaders such as

Chicago Mayor

The mayor of Chicago is the chief executive of city government in Chicago, Illinois, the third-largest city in the United States. The mayor is responsible for the administration and management of various city departments, submits proposals and ...

Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the mayor of Chicago from 1955, and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party from 1953, until his death. He has been called "the last of ...

controlled the delegate votes in their states. Kennedy defeated Branigin and McCarthy in the Indiana primary on May 7, and then defeated McCarthy in the Nebraska primary on May 14. However, McCarthy upset Kennedy in the Oregon primary on May 28.

After Kennedy's defeat in Oregon, the California primary was seen as crucial to both Kennedy and McCarthy. McCarthy stumped the state's many colleges and universities, where he was treated as a hero for being the first presidential candidate to oppose the war. Kennedy campaigned in the

ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

s and

barrio

''Barrio'' () is a Spanish language, Spanish word that means "Quarter (urban subdivision), quarter" or "neighborhood". In the modern Spanish language, it is generally defined as each area of a city delimited by functional (e.g. residential, comm ...

s of the state's larger cities, where he was mobbed by enthusiastic supporters. Kennedy and McCarthy engaged in a television debate a few days before the primary; it was generally considered a draw. On June 4, Kennedy narrowly defeated McCarthy in California, 46%–42%. However, McCarthy refused to withdraw from the race, and made it clear that he would contest Kennedy in the upcoming New York primary on June 18, where McCarthy had much support from anti-war activists. In the early morning of June 5, after giving his victory speech in Los Angeles,

Kennedy was assassinated by

Sirhan Sirhan

Sirhan Bishara Sirhan (; ; born March 19, 1944) is a Palestinian-Jordanian man who assassinated Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a younger brother of American president John F. Kennedy and a candidate for the Democratic nomination in the 1968 U ...

, a 24-year-old

Palestinian-Jordanian

Palestinians in Jordan refers mainly to those with Palestinian refugee status currently residing there. Sometimes the definition includes Jordanian citizens with full Palestinian origin. Most Palestinian ancestors came to Jordan as Palestinian ...

. Kennedy died 26 hours later at

Good Samaritan Hospital. Sirhan admitted his guilt, was convicted of murder, and is still in prison. In recent years some have cast doubt on Sirhan's guilt, including Sirhan himself, who said he was "brainwashed" into killing Kennedy and was a

patsy

Patsy is a given name often used as a diminutive of the feminine given name Patricia or sometimes the masculine name Patrick, or occasionally other names containing the syllable "Pat" (such as Cleopatra, Patience, or Patrice). Among Italian A ...

.

Political historians still debate whether Kennedy could have won the Democratic nomination, had he lived. Some historians, such as

Theodore H. White and

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. ( ; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a ...

, have argued that Kennedy's broad appeal and famed charisma would have convinced the party bosses at the Democratic Convention to give him the nomination. Jack Newfield, author of ''RFK: A Memoir'', stated in a 1998 interview that on the night he was assassinated, "

ennedyhad a phone conversation with Mayor Daley of Chicago, and Mayor Daley all but promised to throw the Illinois delegates to Bobby at the convention in August 1968. I think he said to me, and

Pete Hamill

William Peter Hamill (June 24, 1935August 5, 2020) was an American journalist, novelist, essayist and editor. During his career as a New York City journalist, he was described as "the author of columns that sought to capture the particular flavo ...

: 'Daley is the ball game, and I think we have Daley. However, other writers such as

Tom Wicker

Thomas Grey Wicker (June 18, 1926 – November 25, 2011) was an American journalist. He was best known as a political reporter and columnist for ''The New York Times'' for nearly three decades.

Besides writing non-fiction books about U.S. ...

, who covered the Kennedy campaign for ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', believe that Humphrey's large lead in delegate votes from non-primary states, combined with Senator McCarthy's refusal to quit the race, would have prevented Kennedy from ever winning a majority at the Democratic Convention, and that Humphrey would have been the Democratic nominee, even if Kennedy had lived. The journalist

Richard Reeves and historian

Michael Beschloss

Michael Richard Beschloss (born November 30, 1955) is an American historian specializing in the United States presidency. He is the author of nine books on the presidency.

Early life

Beschloss was born in Chicago, grew up in Flossmoor, Illinois ...

have both written that Humphrey was the likely nominee, and future Democratic National Committee chairman

Larry O'Brien

Lawrence Francis O'Brien Jr. (July 7, 1917September 28, 1990) was an American politician and commissioner of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1975 to 1984. He was one of the United States Democratic Party's leading electoral strat ...

wrote in his memoirs that Kennedy's chances of winning the nomination had been slim, even after his win in California.

At the moment of RFK's death, the delegate totals were:

* Hubert Humphrey – 561

* Robert F. Kennedy – 393

* Eugene McCarthy – 258

Total popular vote:

*

Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

: 2,914,933 (38.7%)

*

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925 – June 6, 1968), also known as RFK, was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 64th United States attorney general from January 1961 to September 1964, and as a U.S. senator from New Yo ...

: 2,304,542 (30.6%)

*

Stephen M. Young: 549,140 (7.3%)

*

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

: 383,048 (5.1%)

*

Roger D. Branigin

Roger Douglas Branigin (July 26, 1902 – November 19, 1975) was an American politician who was the 42nd governor of Indiana, serving from January 11, 1965, to January 13, 1969. A World War II veteran and well-known public speaker, Branigin t ...

: 238,700 (3.2%)

*

George Smathers

George Armistead Smathers (November 14, 1913 – January 20, 2007) was an American lawyer and politician from the state of Florida who served in both chambers of the United States Congress, the United States House of Representatives from 1947 t ...

: 236,242 (3.1%)

*

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

: 166,463 (2.2%)

* Unpledged: 670,328 (8.9%)

*

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

: 33,520 (0.4%)

*

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

(write-in): 13,035 (0.2%)

*

Nelson A. Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

: 5,116 (0.1%)

*

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

(write-in): 4,987 (0.1%)

*

Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts who served as a member of the United States Senate from 1962 to his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party and ...

: 4,052 (0.1%)

* Others: 10,963 (0.1%)

Democratic Convention and antiwar protests

Robert Kennedy's death altered the dynamics of the race. Although Humphrey appeared the presumptive favorite for the nomination, thanks to his support from the traditional power blocs of the party, he was an unpopular choice with many of the

anti-war

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conf ...

elements within the party, who identified him with Johnson's controversial position on the Vietnam War. However, Kennedy's delegates failed to unite behind a single candidate who could have prevented Humphrey from getting the nomination. Some of Kennedy's support went to McCarthy, but many of Kennedy's delegates, remembering their bitter primary battles with McCarthy, refused to vote for him. Instead, these delegates rallied around the late-starting candidacy of Senator

George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American politician, diplomat, and historian who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator from South Dakota, and the Democratic Party (United States), Democ ...

of South Dakota, a Kennedy supporter in the spring primaries who had presidential ambitions himself. This division of the anti-war votes at the Democratic Convention made it easier for Humphrey to gather the delegates he needed to win the nomination.

When the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

opened in Chicago, thousands of young activists from around the nation gathered in the city to

protest the Vietnam War. On the evening of August 28, in a clash which was covered on live television, Americans were shocked to see Chicago police brutally beating anti-war protesters in the streets of Chicago in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel. While the protesters chanted, "

The whole world is watching

"The whole world is watching" was a phrase chanted by anti-Vietnam War demonstrators as they were beaten and arrested by police outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

The event occurred and ...

", the police used clubs and

tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymatory agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the Mace (spray), early commercial self-defense spray, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the ey ...

to beat back or arrest the protesters, leaving many of them bloody and dazed. The tear gas wafted into numerous hotel suites; in one of them Vice President Humphrey was watching the proceedings on television. The police said that their actions were justified because numerous police officers were being injured by bottles, rocks, and broken glass that were being thrown at them by the protestors. The protestors had also yelled insults at the police, calling them "pigs" and other

epithets

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

. The anti-war and police riot divided the Democratic Party's base: some supported the protestors and felt that the police were being heavy-handed, but others disapproved of the violence and supported the police. Meanwhile, the convention itself was marred by the strong-arm tactics of Chicago's mayor Richard J. Daley (who was seen on television angrily cursing Senator

Abraham Ribicoff

Abraham Alexander Ribicoff (April 9, 1910 – February 22, 1998) was an American politician from the state of Connecticut. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Connecticut in the United States House of Representatives and Senate ...

from Connecticut, who made a speech at the convention denouncing the excesses of the Chicago police). In the end, the nomination itself was anticlimactic, with Vice President Humphrey handily beating McCarthy and McGovern on the first ballot.

After the delegates nominated Humphrey, the convention then turned to selecting a vice-presidential nominee. The main candidates for this position were Senators

Edward M. Kennedy from Massachusetts,

Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1980 to 1981, a United States Senator from Maine from 1 ...

from Maine, and

Fred R. Harris

Fred Roy Harris (November 13, 1930 – November 23, 2024) was an American politician from Oklahoma who served from 1957 to 1964 as a member of the Oklahoma Senate and from 1964 to 1973 as a member of the United States Senate.

Harris was electe ...

from Oklahoma; Governors

Richard Hughes of New Jersey and

Terry Sanford

James Terry Sanford (August 20, 1917April 18, 1998) was an American lawyer and politician from North Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, Sanford served as the 65th Governor of North Carolina from 1961 to 1965, was a two-time U.S. pre ...

of North Carolina; Mayor

Joseph Alioto

Joseph Lawrence Alioto (February 12, 1916 – January 29, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 36th mayor of San Francisco, California, from 1968 to 1976.

Biography

Alioto was born in San Francisco in 1916. His father, Giuseppe A ...

of San Francisco, California; former Deputy Secretary of Defense

Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as the 57th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United ...

; and Ambassador

Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. He was a member of the Shriver family by birth, and a member of the Kennedy family through his marriage to Eunice Kennedy. ...

from Maryland. Another idea floated was to tap Republican Governor

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

of New York, one of the most liberal Republicans. Ted Kennedy was Humphrey's first choice, but the senator turned him down. After narrowing it down to Senator Muskie and Senator Harris, Vice President Humphrey chose Muskie, a moderate and

environmentalist