1941 Invasion Of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Barbarossa was the

While older histories tended to emphasize the myth of the "clean ''Wehrmacht,''" upholding its honor in the face of Hitler's fanaticism, historian

While older histories tended to emphasize the myth of the "clean ''Wehrmacht,''" upholding its honor in the face of Hitler's fanaticism, historian

Stalin's reputation as a brutal dictator contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their expectations of success, as Stalin's

Stalin's reputation as a brutal dictator contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their expectations of success, as Stalin's

The importance of the delay is still debated.

The importance of the delay is still debated.

In early 1941, Stalin authorised the State Defence Plan 1941 (DP-41), which along with the Mobilisation Plan 1941 (MP-41), called for the deployment of 186 divisions, as the first strategic echelon, in the four military districts of the western Soviet Union that faced the Axis territories; and the deployment of another 51 divisions along the Dvina and Dnieper Rivers as the second strategic echelon under

In early 1941, Stalin authorised the State Defence Plan 1941 (DP-41), which along with the Mobilisation Plan 1941 (MP-41), called for the deployment of 186 divisions, as the first strategic echelon, in the four military districts of the western Soviet Union that faced the Axis territories; and the deployment of another 51 divisions along the Dvina and Dnieper Rivers as the second strategic echelon under

At around 01:00 on Sunday, 22 June 1941, the Soviet military districts in the border area were alerted by NKO Directive No. 1, issued late on the night of 21 June. It called on them to "bring all forces to combat readiness", but to "avoid provocative actions of any kind". It took up to two hours for several of the units subordinate to the Fronts to receive the order of the directive, and the majority did not receive it before the invasion commenced. A German communist deserter,

At around 01:00 on Sunday, 22 June 1941, the Soviet military districts in the border area were alerted by NKO Directive No. 1, issued late on the night of 21 June. It called on them to "bring all forces to combat readiness", but to "avoid provocative actions of any kind". It took up to two hours for several of the units subordinate to the Fronts to receive the order of the directive, and the majority did not receive it before the invasion commenced. A German communist deserter,

The initial momentum of the German ground and air attack completely destroyed the Soviet organisational command and control within the first few hours, paralyzing every level of command from the infantry platoon to the Soviet High Command in Moscow. Moscow failed to grasp the magnitude of the catastrophe that confronted the Soviet forces in the border area, and Stalin's first reaction was disbelief. At around 07:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 2, which announced the invasion to the Soviet Armed Forces, and called on them to attack Axis forces wherever they had violated the borders and launch air strikes into the border regions of German territory. At around 09:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 3, signed by Timoshenko, which now called for a general counteroffensive on the entire front "without any regards for borders" that both men hoped would sweep the enemy from Soviet territory. Stalin's order, which Timoshenko authorised, was not based on a realistic appraisal of the military situation at hand, but commanders passed it along for fear of retribution if they failed to obey; several days passed before the Soviet leadership became aware of the enormity of the opening defeat, and before Stalin comprehended the magnitude of the calamity. Significant amounts of Soviet territory were lost along with Red Army forces as a result.

The initial momentum of the German ground and air attack completely destroyed the Soviet organisational command and control within the first few hours, paralyzing every level of command from the infantry platoon to the Soviet High Command in Moscow. Moscow failed to grasp the magnitude of the catastrophe that confronted the Soviet forces in the border area, and Stalin's first reaction was disbelief. At around 07:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 2, which announced the invasion to the Soviet Armed Forces, and called on them to attack Axis forces wherever they had violated the borders and launch air strikes into the border regions of German territory. At around 09:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 3, signed by Timoshenko, which now called for a general counteroffensive on the entire front "without any regards for borders" that both men hoped would sweep the enemy from Soviet territory. Stalin's order, which Timoshenko authorised, was not based on a realistic appraisal of the military situation at hand, but commanders passed it along for fear of retribution if they failed to obey; several days passed before the Soviet leadership became aware of the enormity of the opening defeat, and before Stalin comprehended the magnitude of the calamity. Significant amounts of Soviet territory were lost along with Red Army forces as a result.

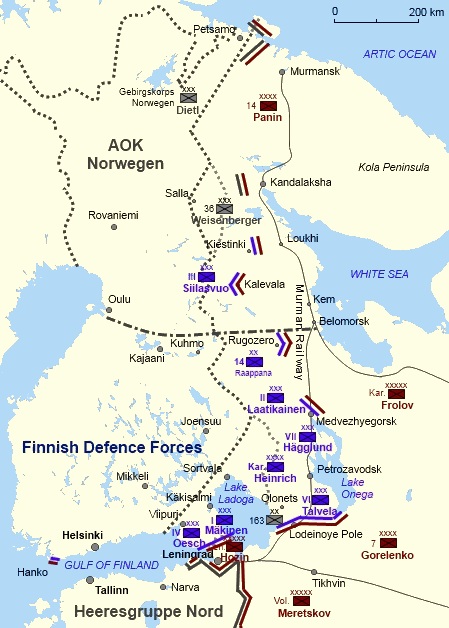

During German-Finnish negotiations, Finland had demanded to remain neutral unless the Soviet Union attacked them first. Germany therefore sought to provoke the Soviet Union into an attack on Finland. After Germany launched Barbarossa on 22 June, German aircraft used Finnish air bases to attack Soviet positions. The same day the Germans launched

During German-Finnish negotiations, Finland had demanded to remain neutral unless the Soviet Union attacked them first. Germany therefore sought to provoke the Soviet Union into an attack on Finland. After Germany launched Barbarossa on 22 June, German aircraft used Finnish air bases to attack Soviet positions. The same day the Germans launched

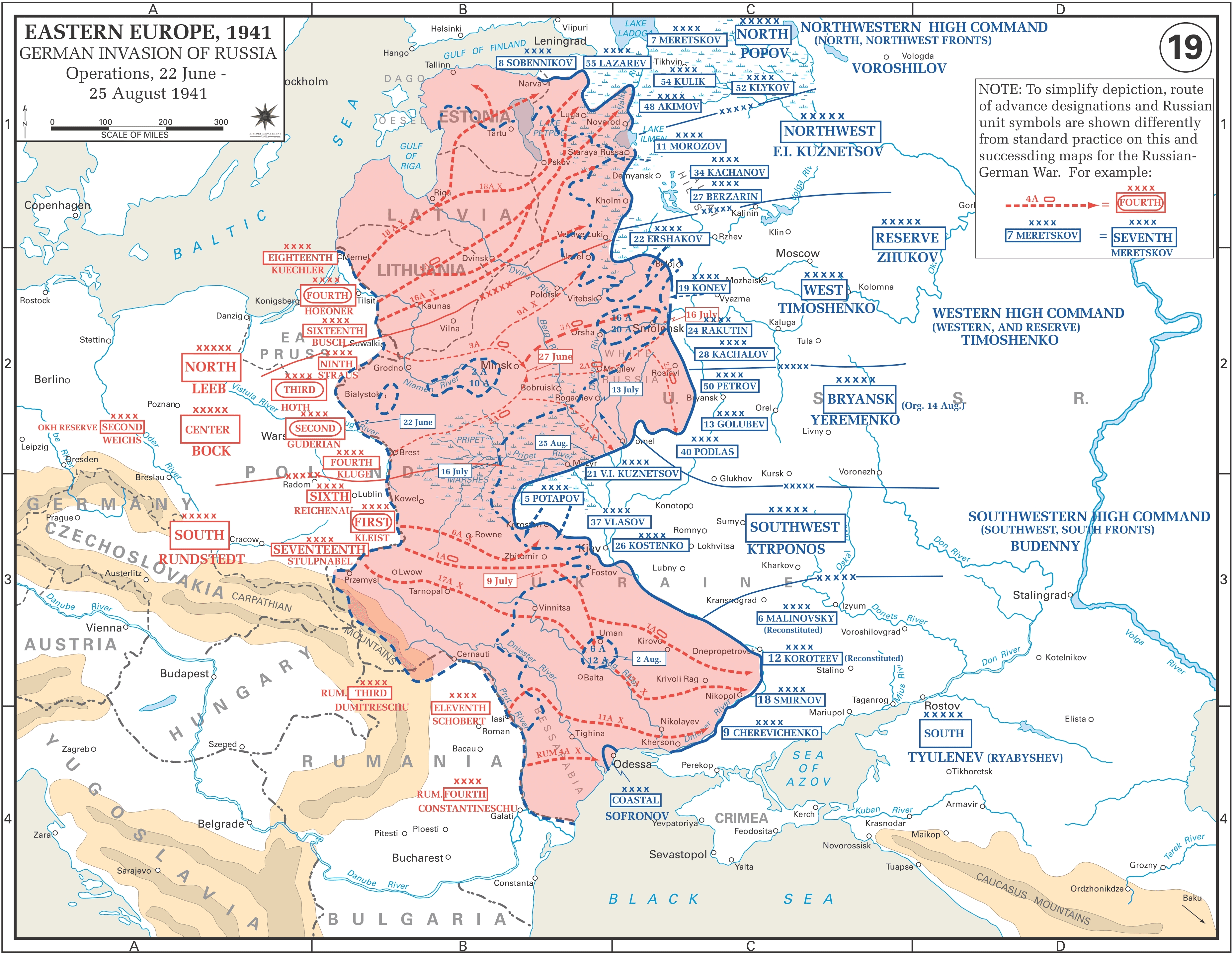

On 2 July and through the next six days, a rainstorm typical of Belarusian summers slowed the progress of the panzers of Army Group Centre, and Soviet defences stiffened. The delays gave the Soviets time to organise a massive counterattack against Army Group Centre. The army group's ultimate objective was Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On 6 July, the Soviets launched a massive counter-attack using the V and VII Mechanised Corps of the 20th Army, which collided with the German 39th and 47th Panzer Corps in a battle where the Red Army lost 832 tanks of the 2,000 employed during five days of ferocious fighting. The Germans defeated this counterattack thanks largely to the coincidental presence of the ''Luftwaffe''s only squadron of tank-busting aircraft. The 2nd Panzer Group crossed the Dnieper River and closed in on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Group, after defeating the Soviet counterattack, closed on Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. The 29th Motorised Division captured Smolensk on 16 July yet a gap remained between Army Group Centre. On 18 July, the panzer groups came to within of closing the gap but the trap did not finally close until 5 August, when upwards of 300,000 Red Army soldiers had been captured and 3,205 Soviet tanks were destroyed. Large numbers of Red Army soldiers escaped to stand between the Germans and Moscow as resistance continued.

Four weeks into the campaign, the Germans realised they had grossly underestimated Soviet strength. The German troops had used their initial supplies, and General Bock quickly came to the conclusion that not only had the Red Army offered stiff opposition, but German difficulties were also due to the logistical problems with reinforcements and provisions. Operations were now slowed down to allow for resupply; the delay was to be used to adapt strategy to the new situation. In addition to strained logistics, poor roads made it difficult for wheeled vehicles and foot infantry to keep up with the faster armoured spearheads, and shortages in boots and winter uniforms were becoming apparent. Furthermore, all three army groups had suffered 179,500 casualties by 2 August, and had only received 47,000 replacements.

Hitler by now had lost faith in battles of encirclement as large numbers of Soviet soldiers had escaped the pincers. He now believed he could defeat the Soviet state by economic means, depriving them of the industrial capacity to continue the war. That meant seizing the industrial centre of

On 2 July and through the next six days, a rainstorm typical of Belarusian summers slowed the progress of the panzers of Army Group Centre, and Soviet defences stiffened. The delays gave the Soviets time to organise a massive counterattack against Army Group Centre. The army group's ultimate objective was Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On 6 July, the Soviets launched a massive counter-attack using the V and VII Mechanised Corps of the 20th Army, which collided with the German 39th and 47th Panzer Corps in a battle where the Red Army lost 832 tanks of the 2,000 employed during five days of ferocious fighting. The Germans defeated this counterattack thanks largely to the coincidental presence of the ''Luftwaffe''s only squadron of tank-busting aircraft. The 2nd Panzer Group crossed the Dnieper River and closed in on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Group, after defeating the Soviet counterattack, closed on Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. The 29th Motorised Division captured Smolensk on 16 July yet a gap remained between Army Group Centre. On 18 July, the panzer groups came to within of closing the gap but the trap did not finally close until 5 August, when upwards of 300,000 Red Army soldiers had been captured and 3,205 Soviet tanks were destroyed. Large numbers of Red Army soldiers escaped to stand between the Germans and Moscow as resistance continued.

Four weeks into the campaign, the Germans realised they had grossly underestimated Soviet strength. The German troops had used their initial supplies, and General Bock quickly came to the conclusion that not only had the Red Army offered stiff opposition, but German difficulties were also due to the logistical problems with reinforcements and provisions. Operations were now slowed down to allow for resupply; the delay was to be used to adapt strategy to the new situation. In addition to strained logistics, poor roads made it difficult for wheeled vehicles and foot infantry to keep up with the faster armoured spearheads, and shortages in boots and winter uniforms were becoming apparent. Furthermore, all three army groups had suffered 179,500 casualties by 2 August, and had only received 47,000 replacements.

Hitler by now had lost faith in battles of encirclement as large numbers of Soviet soldiers had escaped the pincers. He now believed he could defeat the Soviet state by economic means, depriving them of the industrial capacity to continue the war. That meant seizing the industrial centre of

In central Finland, the German-Finnish advance on the Murmansk railway had been resumed at Kayraly. A large encirclement from the north and the south trapped the defending Soviet corps and allowed XXXVI Corps to advance further to the east. In early September it reached the old 1939 Soviet border fortifications. On 6 September the first defence line at the Voyta River was breached, but further attacks against the main line at the Verman River failed. With Army Norway switching its main effort further south, the front stalemated in this sector. Further south, the Finnish III Corps launched a new offensive towards the Murmansk railway on 30 October, bolstered by fresh reinforcements from Army Norway. Against Soviet resistance, it was able to come within of the railway, when the Finnish High Command ordered a stop to all offensive operations in the sector on 17 November. The United States of America applied diplomatic pressure on Finland not to disrupt Allied aid shipments to the Soviet Union, which caused the Finnish government to halt the advance on the Murmansk railway. With the Finnish refusal to conduct further offensive operations and German inability to do so alone, the German-Finnish effort in central and northern Finland came to an end.

In central Finland, the German-Finnish advance on the Murmansk railway had been resumed at Kayraly. A large encirclement from the north and the south trapped the defending Soviet corps and allowed XXXVI Corps to advance further to the east. In early September it reached the old 1939 Soviet border fortifications. On 6 September the first defence line at the Voyta River was breached, but further attacks against the main line at the Verman River failed. With Army Norway switching its main effort further south, the front stalemated in this sector. Further south, the Finnish III Corps launched a new offensive towards the Murmansk railway on 30 October, bolstered by fresh reinforcements from Army Norway. Against Soviet resistance, it was able to come within of the railway, when the Finnish High Command ordered a stop to all offensive operations in the sector on 17 November. The United States of America applied diplomatic pressure on Finland not to disrupt Allied aid shipments to the Soviet Union, which caused the Finnish government to halt the advance on the Murmansk railway. With the Finnish refusal to conduct further offensive operations and German inability to do so alone, the German-Finnish effort in central and northern Finland came to an end.

After Kiev, the Red Army no longer outnumbered the Germans and there were no more trained reserves directly available. To defend Moscow, Stalin could field 800,000 men in 83 divisions, but no more than 25 divisions were fully effective. Operation Typhoon, the drive to Moscow, began on 30 September 1941. In front of Army Group Centre was a series of elaborate defence lines, the first centred on Vyazma and the second on Mozhaysk. Russian peasants began fleeing ahead of the advancing German units, burning their harvested crops, driving their cattle away, and destroying buildings in their villages as part of a scorched-earth policy designed to deny to the Nazi war machine needed supplies and foodstuffs.

The first blow took the Soviets completely by surprise when the 2nd Panzer Group, returning from the south, took Oryol, just south of the Soviet first main defence line. Three days later, the Panzers pushed on to Bryansk, while the 2nd Army attacked from the west. The Soviet 3rd and 13th Armies were now encircled. To the north, the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies attacked Vyazma, trapping the 19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd Armies. Moscow's first line of defence had been shattered. The pocket eventually yielded over 500,000 Soviet prisoners, bringing the tally since the start of the invasion to three million. The Soviets now had only 90,000 men and 150 tanks left for the defence of Moscow.

The German government now publicly predicted the imminent capture of Moscow and convinced foreign correspondents of an impending Soviet collapse. On 13 October, the 3rd Panzer Group penetrated to within of the capital. Martial law was declared in Moscow. Almost from the beginning of Operation Typhoon, however, the weather worsened. Temperatures fell while there was continued rainfall. This turned the unpaved road network Rasputitsa, into mud and slowed the German advance on Moscow. Additional snows fell which were followed by more rain, creating a glutinous mud that German tanks had difficulty traversing, which the Soviet T-34, with its wider tread, was better suited to navigate. At the same time, the supply situation for the Germans rapidly deteriorated. On 31 October, the German Army High Command ordered a halt to Operation Typhoon while the armies were reorganised. The pause gave the Soviets, far better supplied, time to consolidate their positions and organise formations of newly activated reservists. In little over a month, the Soviets organised eleven new armies that included 30 divisions of Siberian troops. These had been freed from the Soviet Far East after Soviet intelligence assured Stalin that there was no longer a threat from Imperial Japan. During October and November 1941, over 1,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft arrived along with the Siberian forces to assist in defending the city.

With the ground hardening due to the cold weather, the Germans resumed the attack on Moscow on 15 November. Although the troops themselves were now able to advance again, there had been no improvement in the supply situation; only 135,000 of the 600,000 trucks that had been available on 22 June 1941 were available by 15 November 1941. Ammunition and fuel supplies were prioritised over food and winter clothing, so many German troops looted supplies from local populations, but could not fill their needs.

Facing the Germans were the 5th, 16th, 30th, 43rd, 49th, and 50th Soviet Armies. The Germans intended to move the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies across the Moscow Canal and envelop Moscow from the northeast. The 2nd Panzer Group would attack Tula, Russia, Tula and then close on Moscow from the south. As the Soviets reacted to their flanks, the 4th Army would attack the centre. In two weeks of fighting, lacking sufficient fuel and ammunition, the Germans slowly crept towards Moscow. In the south, the 2nd Panzer Group was being blocked. On 22 November, Soviet Siberian units, augmented by the 49th and 50th Soviet Armies, attacked the 2nd Panzer Group and inflicted a defeat on the Germans. The 4th Panzer Group pushed the Soviet 16th Army back, however, and succeeded in crossing the Moscow Canal in an attempt to encircle Moscow.

On 2 December, part of the 258th Infantry Division advanced to within of Moscow. They were so close that German officers claimed they could see the spires of the Moscow Kremlin, Kremlin, but by then the first blizzards had begun. A reconnaissance battalion managed to reach the town of Khimki#History, Khimki, only about from the Soviet capital. It captured the bridge over the Moscow-Volga Canal as well as the railway station, which marked the easternmost advance of German forces. In spite of the progress made, the ''Wehrmacht'' was not equipped for such severe winter warfare. The Soviet army was better adapted to fighting in winter conditions, but faced production shortages of winter clothing. The German forces fared worse, with deep snow further hindering equipment and mobility. Weather conditions had largely grounded the ''Luftwaffe'', preventing large-scale air operations. Newly created Soviet units near Moscow now numbered over 500,000 men, who despite their inexperience, were able to halt the German offensive by 5 December due to Defence in depth, superior defensive fortifications, the presence of skilled and experienced leadership like Georgy Zhukov, Zhukov, and the poor German situation. On 5 December, the Soviet defenders launched a massive counterattack as part of the Battle of Moscow#Soviet counter-offensive, Soviet winter counteroffensive. The offensive halted on 7 January 1942, after having pushed the German armies back from Moscow. The ''Wehrmacht'' had lost the Battle for Moscow, and the invasion had cost the German Army over 830,000 men.

After Kiev, the Red Army no longer outnumbered the Germans and there were no more trained reserves directly available. To defend Moscow, Stalin could field 800,000 men in 83 divisions, but no more than 25 divisions were fully effective. Operation Typhoon, the drive to Moscow, began on 30 September 1941. In front of Army Group Centre was a series of elaborate defence lines, the first centred on Vyazma and the second on Mozhaysk. Russian peasants began fleeing ahead of the advancing German units, burning their harvested crops, driving their cattle away, and destroying buildings in their villages as part of a scorched-earth policy designed to deny to the Nazi war machine needed supplies and foodstuffs.

The first blow took the Soviets completely by surprise when the 2nd Panzer Group, returning from the south, took Oryol, just south of the Soviet first main defence line. Three days later, the Panzers pushed on to Bryansk, while the 2nd Army attacked from the west. The Soviet 3rd and 13th Armies were now encircled. To the north, the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies attacked Vyazma, trapping the 19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd Armies. Moscow's first line of defence had been shattered. The pocket eventually yielded over 500,000 Soviet prisoners, bringing the tally since the start of the invasion to three million. The Soviets now had only 90,000 men and 150 tanks left for the defence of Moscow.

The German government now publicly predicted the imminent capture of Moscow and convinced foreign correspondents of an impending Soviet collapse. On 13 October, the 3rd Panzer Group penetrated to within of the capital. Martial law was declared in Moscow. Almost from the beginning of Operation Typhoon, however, the weather worsened. Temperatures fell while there was continued rainfall. This turned the unpaved road network Rasputitsa, into mud and slowed the German advance on Moscow. Additional snows fell which were followed by more rain, creating a glutinous mud that German tanks had difficulty traversing, which the Soviet T-34, with its wider tread, was better suited to navigate. At the same time, the supply situation for the Germans rapidly deteriorated. On 31 October, the German Army High Command ordered a halt to Operation Typhoon while the armies were reorganised. The pause gave the Soviets, far better supplied, time to consolidate their positions and organise formations of newly activated reservists. In little over a month, the Soviets organised eleven new armies that included 30 divisions of Siberian troops. These had been freed from the Soviet Far East after Soviet intelligence assured Stalin that there was no longer a threat from Imperial Japan. During October and November 1941, over 1,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft arrived along with the Siberian forces to assist in defending the city.

With the ground hardening due to the cold weather, the Germans resumed the attack on Moscow on 15 November. Although the troops themselves were now able to advance again, there had been no improvement in the supply situation; only 135,000 of the 600,000 trucks that had been available on 22 June 1941 were available by 15 November 1941. Ammunition and fuel supplies were prioritised over food and winter clothing, so many German troops looted supplies from local populations, but could not fill their needs.

Facing the Germans were the 5th, 16th, 30th, 43rd, 49th, and 50th Soviet Armies. The Germans intended to move the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies across the Moscow Canal and envelop Moscow from the northeast. The 2nd Panzer Group would attack Tula, Russia, Tula and then close on Moscow from the south. As the Soviets reacted to their flanks, the 4th Army would attack the centre. In two weeks of fighting, lacking sufficient fuel and ammunition, the Germans slowly crept towards Moscow. In the south, the 2nd Panzer Group was being blocked. On 22 November, Soviet Siberian units, augmented by the 49th and 50th Soviet Armies, attacked the 2nd Panzer Group and inflicted a defeat on the Germans. The 4th Panzer Group pushed the Soviet 16th Army back, however, and succeeded in crossing the Moscow Canal in an attempt to encircle Moscow.

On 2 December, part of the 258th Infantry Division advanced to within of Moscow. They were so close that German officers claimed they could see the spires of the Moscow Kremlin, Kremlin, but by then the first blizzards had begun. A reconnaissance battalion managed to reach the town of Khimki#History, Khimki, only about from the Soviet capital. It captured the bridge over the Moscow-Volga Canal as well as the railway station, which marked the easternmost advance of German forces. In spite of the progress made, the ''Wehrmacht'' was not equipped for such severe winter warfare. The Soviet army was better adapted to fighting in winter conditions, but faced production shortages of winter clothing. The German forces fared worse, with deep snow further hindering equipment and mobility. Weather conditions had largely grounded the ''Luftwaffe'', preventing large-scale air operations. Newly created Soviet units near Moscow now numbered over 500,000 men, who despite their inexperience, were able to halt the German offensive by 5 December due to Defence in depth, superior defensive fortifications, the presence of skilled and experienced leadership like Georgy Zhukov, Zhukov, and the poor German situation. On 5 December, the Soviet defenders launched a massive counterattack as part of the Battle of Moscow#Soviet counter-offensive, Soviet winter counteroffensive. The offensive halted on 7 January 1942, after having pushed the German armies back from Moscow. The ''Wehrmacht'' had lost the Battle for Moscow, and the invasion had cost the German Army over 830,000 men.

Marking 70 Years to Operation Barbarossa

on the Yad Vashem website

Operation Barbarossa

original reports and pictures from ''The Times'' * "Operation Barbarossa": , lecture by David Stahel, author of ''Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East'' (2009); via the official channel of Muskegon Community College {{DEFAULTSORT:Barbarossa Operation Barbarossa, Articles containing video clips Code names Invasions of Russia June 1941 in Europe Military operations involving Finland Military operations of World War II Invasions of Ukraine

invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and several of its European Axis allies

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a front, with the main goal of capturing territory up to a line between Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the ...

and Astrakhan

Astrakhan (, ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the Caspian Depression, from the Caspian Se ...

, known as the A-A line

The Arkhangelsk–Astrakhan line, or A–A line for short, was the military goal of Operation Barbarossa. It is also known as the Volga–Arkhangelsk line, as well as (more rarely) the Volga–Arkhangelsk–Astrakhan line. It was first mentioned ...

. The attack became the largest and costliest military offensive in history, with around 10 million combatants taking part in the opening phase and over 8 million casualties by the end of the operation on 5 December 1941. It marked a major escalation of World War II, opened the Eastern Front—the largest and deadliest land war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

in history—and brought the Soviet Union into the Allied powers.

The operation, code-named after the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

("red beard"), put into action Nazi Germany's ideological goals of eradicating communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and conquering the western Soviet Union to repopulate it with Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

under , which planned for the extermination of the native Slavic peoples

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, Southeast ...

by mass deportation to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people, and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In l ...

, enslavement, and genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

. The material targets of the invasion were the agricultural and mineral resources of territories such as Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and Byelorussia and oil fields in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

. The Axis eventually captured five million Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

troops on the Eastern Front and deliberately starved to death or otherwise killed 3.3 million prisoners of war, as well as millions of civilians. Mass shootings

A mass shooting is a violent crime in which one or more attackers use a firearm to Gun violence, kill or injure multiple individuals in rapid succession. There is no widely accepted specific definition, and different organizations tracking su ...

and gassing operations, carried out by German paramilitary death squads and collaborators, murdered over a million Soviet Jews

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "Fo ...

as part of the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. In the two years leading up to the invasion, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed political and economic pacts for strategic purposes. Following the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

Between 28 June and 3 July 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, following an ultimatum made to Romania on 26 June 1940 that threatened the use of force. Those regions, with a total area of and a population of 3,776 ...

in July 1940, the German High Command began planning an invasion of the country, which was approved by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

in December. In early 1941, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, despite receiving intelligence about an imminent attack, did not order a mobilization of the Red Army, fearing that it might provoke Germany. As a result, Soviet forces were largely caught unprepared when the invasion began, with many units positioned poorly and understrength.

The invasion began on 22 June 1941 with a massive ground and air assault. The main part of Army Group South

Army Group South () was the name of one of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland, Army Group South was led by Ge ...

invaded from occupied Poland on 22 June, and on 2 July was joined by a combination of German and Romanian forces attacking from Romania. Kiev was captured on 19 September, which was followed by the captures of Kharkov on 24 October and Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

on 20 November, by which time most of Crimea had been captured and Sevastopol put under siege. Army Group North

Army Group North () was the name of three separate army groups of the Wehrmacht during World War II. Its rear area operations were organized by the Army Group North Rear Area.

The first Army Group North was deployed during the invasion of Pol ...

overran the Baltic lands, and on 8 September 1941 began a siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

with Finnish forces that ultimately lasted until 1944. Army Group Centre

Army Group Centre () was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created during the planning of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the So ...

, the strongest of the three groups, captured Smolensk in late July 1941 before beginning a drive on Moscow on 2 October. Facing logistical problems with supply, slowed by muddy terrain, not fully outfitted for Russia's brutal winter, and coping with determined Soviet resistance, Army Group Centre's offensive stalled at the city's outskirts by 5 December, at which point the Soviets began a major counteroffensive.

The failure of Operation Barbarossa reversed the fortunes of Nazi Germany. Operationally, it achieved significant victories and occupied some of the most important economic regions of the Soviet Union, captured millions of prisoners, and inflicted heavy casualties. The German high command anticipated a quick collapse of resistance as in the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, but instead the Red Army absorbed the German ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

''s strongest blows and bogged it down in a war of attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

for which Germany was unprepared. Following the heavy losses and logistical strain of Barbarossa, German forces could no longer attack along the entire front, and their subsequent operations—such as Case Blue

Case Blue (German: ''Fall Blau'') was the ''Wehrmacht'' plan for the 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and 24 November 1942, during World War II. The objective was to capture the oil fields of Baku ( Azerb ...

in 1942 and Operation Citadel

Operation Citadel () was the German offensive operation in July 1943 against Soviet forces in the Kursk salient, proposed by Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein during the Second World War on the Eastern Front that initiated the Battle of ...

in 1943—ultimately failed.

Background

Naming

The theme of Barbarossa had long been used by theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

as part of their political imagery, though this was really a continuation of the glorification of the famous Crusader king by German nationalists since the 19th century. According to a Germanic medieval legend, revived in the 19th century by the nationalistic tropes of German Romanticism

German Romanticism () was the dominant intellectual movement of German-speaking countries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influencing philosophy, aesthetics, literature, and criticism. Compared to English Romanticism, the German vari ...

, the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

—who drowned in Asia Minor while leading the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

—was not dead but asleep, along with his knights, in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

, and would awaken in the hour of Germany's greatest need and restore the nation to its former glory. Originally, the invasion of the Soviet Union was codenamed ''Operation Otto

Operation Otto, also known as Plan Otto, was the code name for two independent plans by Nazi Germany. The 1938 plan was to occupy Austria; the second envisaged an attack on the Soviet Union and was developed from late July 1940.

The Two Plans

The ...

'' (alluding to Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), known as Otto the Great ( ) or Otto of Saxony ( ), was East Frankish ( German) king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the eldest son of Henry the Fowler and Matilda ...

's expansive campaigns in Eastern Europe), but Hitler had the name changed to ''Operation Barbarossa'' in December 1940. Hitler had in July 1937 praised Barbarossa as the emperor who first expressed Germanic cultural ideas and carried them to the outside world through his imperial mission. For Hitler, the name Barbarossa signified his belief that the conquest of the Soviet Union would usher in the Nazi " Thousand-Year Reich".

Racial policies of Nazi Germany

As early as 1925,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

vaguely declared in his political manifesto and autobiography ''Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'' that he would invade the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, asserting that the German people needed to secure ('living space') to ensure the survival of Germany for generations to come. On 10 February 1939, Hitler told his army commanders that the next war would be "purely a war of worldviews'.. totally a people's war, a racial war

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's position within so ...

". On 23 November, once World War II had already started, Hitler declared that "racial war has broken out and this war shall determine who shall govern Europe, and with it, the world". The racial policy of Nazi Germany

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on pseudoscientific and racist doctrines asserting the superiority of the putative "Aryan race", which cl ...

portrayed the Soviet Union (and all of Eastern Europe) as populated by non-Aryan ('sub-humans'), ruled by Jewish Bolshevik

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist movement ...

conspirators. Hitler claimed in ''Mein Kampf'' that Germany's destiny was to follow the ('turn to the East') as it did "600 years ago" (see ). Accordingly, it was a partially secret but well-documented Nazi policy to kill, deport, or enslave the majority of Russian and other Slavic populations and repopulate the land west of the Urals with Germanic peoples, under (General Plan for the East). The Nazis' belief in their ethnic superiority pervades official records and pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

articles in German periodicals, on topics such as "how to deal with alien populations."

Jürgen Förster

Jürgen Förster (born 1940) is a German historian who specialises in the history of Nazi Germany and World War II. He is a professor of history at the University of Freiburg, the position he has held since 2005. Förster is a contributor to t ...

notes that "In fact, the military commanders were caught up in the ideological character of the conflict, and involved in its implementation as willing participants". Before and during the invasion of the Soviet Union, German troops were indoctrinated with anti-Bolshevik, anti-Semitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and anti-Slavic

Anti-Slavic sentiment, also called Slavophobia, refers to prejudice, collective hatred, and discrimination directed at the various Slavic peoples. Accompanying racism and xenophobia, the most common manifestation of anti-Slavic sentiment througho ...

ideology via movies, radio, lectures, books, and leaflets. Likening the Soviets to the forces of Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan (title), khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongols, Mongol tribes, he launched Mongol invasions and ...

, Hitler told the Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

n military leader Slavko Kvaternik

Slavko Kvaternik (25 August 1878 – 7 June 1947) was a Croatian military general and politician who was one of the founders of the ultranationalist Ustaše movement. Kvaternik was military commander and Minister of the Armed Forces ('' Domobrans ...

that the "Mongolian race" threatened Europe. Following the invasion, many ''Wehrmacht'' officers told their soldiers to target people who were described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans," the "Mongol hordes," the "Asiatic flood" and the "Red beast." Nazi propaganda portrayed the war against the Soviet Union as an ideological war between German National Socialism and Jewish Bolshevism and a racial war between the disciplined Germans and the Jewish, Romani and Slavic . An 'order from the Führer' stated that the paramilitary SS , which closely followed the ''Wehrmacht''s advance, were to execute all Soviet functionaries who were "less valuable Asiatics, Gypsies and Jews." Six months into the invasion of the Soviet Union, the had murdered more than 500,000 Soviet Jews, a figure greater than the number of Red Army soldiers killed in battle by then. German army commanders cast Jews as the major cause behind the "partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

struggle." The main guideline for German troops was "Where there's a partisan, there's a Jew, and where there's a Jew, there's a partisan" or "The partisan is where the Jew is." Many German troops viewed the war in Nazi terms and regarded their Soviet enemies as sub-human.

After the war began, the Nazis issued a ban on sexual relations between Germans and foreign slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. There were regulations enacted against the ('Eastern workers') that included the death penalty for sexual relations with a German. Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

, in his secret memorandum, ''Reflections on the Treatment of Peoples of Alien Races in the East'' (dated 25 May 1940), outlined the Nazi plans for the non-German populations in the East. Himmler believed the Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people, and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In l ...

process in Eastern Europe would be complete when "in the East dwell only men with truly German, Germanic blood."

The Nazi secret plan , prepared in 1941 and confirmed in 1942, called for a "new order of ethnographical relations" in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe. It envisaged ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

, executions and enslavement of the populations of conquered countries, with very small percentages undergoing Germanisation, expulsion into the depths of Russia or other fates, while the conquered territories would be Germanised. The plan had two parts, the ('small plan'), which covered actions to be taken during the war and the ('large plan'), which covered policies after the war was won, to be implemented gradually over 25 to 30 years.

A speech given by General Erich Hoepner

Erich Kurt Richard Hoepner (14 September 1886 – 8 August 1944) was a German general during World War II. An early proponent of mechanisation and armoured warfare, he was a Wehrmacht Heer army corps commander at the beginning of the war, lead ...

demonstrates the dissemination of the Nazi racial plan, as he informed the 4th Panzer Group

The 4th Panzer Army (), operating as Panzer Group 4 () from its formation on 15 February 1941 to 1 January 1942, was a German panzer formation during World War II. As a key armoured component of the Wehrmacht, the army took part in the crucial ...

that the war against the Soviet Union was "an essential part of the German people's struggle for existence" (), also referring to the imminent battle as the "old struggle of Germans against Slavs" and even stated, "the struggle must aim at the annihilation of today's Russia and must, therefore, be waged with unparalleled harshness." Hoepner also added that the Germans were fighting for "the defence of European culture against Moscovite–Asiatic inundation, and the repulse of Jewish Bolshevism ... No adherents of the present Russian-Bolshevik system are to be spared." Walther von Brauchitsch

Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch (4 October 1881 – 18 October 1948) was a German ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) and Commander-in-Chief (''Oberbefehlshaber'') of the German Army during the first two years of World War ...

also told his subordinates that troops should view the war as a "struggle between two different races and houldact with the necessary severity." Racial motivations were central to Nazi ideology and played a key role in planning for Operation Barbarossa since both Jews and communists were considered equivalent enemies of the Nazi state. Nazi imperialist ambitions rejected the common humanity of both groups, declaring the supreme struggle for to be a ('war of annihilation').

German-Soviet relations of 1939–40

On August 23, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact in Moscow known as theMolotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

. A secret protocol to the pact outlined an agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union on the division of the eastern European border states between their respective "spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

," Soviet Union and Germany would partition Poland in the event of an invasion by Germany, and the Soviets would be allowed to overrun Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

and the region of Bessarabia

Bessarabia () is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Bessarabia lies within modern-day Moldova, with the Budjak region covering the southern coa ...

. On 23 August 1939 the rest of the world learned of this pact but were unaware of the provisions to partition Poland. The pact stunned the world because of the parties' earlier mutual hostility and their conflicting ideologies

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

. The conclusion of this pact was followed by the German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

on 1 September that triggered the outbreak of World War II in Europe

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II, taking place from September 1939 to May 1945. The Allied powers (including the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union and Franc ...

, then the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military conflict by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Second Polish Republic, Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Polan ...

that led to the annexation of the eastern part of the country. As a result of the pact, Germany and the Soviet Union maintained reasonably strong diplomatic relations for two years and fostered an important economic relationship. The countries entered a trade pact in 1940 by which the Soviets received German military equipment and trade goods in exchange for raw materials, such as oil and wheat, to help the German war effort

War effort is a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and civilian—towards the support of a military force, particular during a state of war. Depending on the militarization of the culture, the relative si ...

by circumventing the British blockade of Germany Blockade of Germany may refer to:

*Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)

The Blockade of Germany, or the Blockade of Europe, occurred from 1914 to 1919. The prolonged naval blockade was conducted by the Allies of World War I, Allies during and afte ...

.

Despite the parties' ostensibly cordial relations, each side was highly suspicious of the other's intentions. For instance, the Soviet invasion of Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

in June 1940 went beyond their sphere of influence as agreed with Germany. After Germany entered the Axis Pact with Japan and Italy, it began negotiations about a potential Soviet entry into the pact. After two days of negotiations in Berlin from 12 to 14 November 1940, Ribbentrop presented a draft treaty for a Soviet entry into the Axis. However, Hitler had no intention of allowing the Soviet Union into the Axis and in an order stated, "Political conversations designed to clarify the attitude of Russia in the immediate future have been started. Regardless of the outcome of these conversations, all preparations for the East previously ordered orally are to be continued. ritten

Ritten (; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in South Tyrol in northern Italy.

Territory

The community is named after the high plateau, elevation , the Ritten or the Renon, on which most of the villages are located. The plateau forms the southe ...

directives on that will follow as soon as the basic elements of the army's plan for the operation have been submitted to me and approved by me." There would be no "long-term agreement with Russia" given that the Nazis intended to go to war with them; but the Soviets approached the negotiations differently and were willing to make huge economic concessions to secure a relationship under general terms acceptable to the Germans just a year before. On 25 November 1940, the Soviet Union offered a written counter-proposal to join the Axis if Germany would agree to refrain from interference in the Soviet Union's sphere of influence, but Germany did not respond. As both sides began colliding with each other in Eastern Europe, conflict appeared more likely, although they did sign a border and commercial agreement addressing several open issues in January 1941. According to historian Robert Service, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

was convinced that the overall military strength of the Soviet Union was such that he had nothing to fear and anticipated an easy victory should Germany attack; moreover, Stalin believed that since the Germans were still fighting the British in the west, Hitler would be unlikely to open up a two-front war and subsequently delayed the reconstruction of defensive fortifications in the border regions. When German soldiers swam across the Bug River

The Bug or Western Bug is a major river in Central Europe that flows through Belarus (border), Poland, and Ukraine, with a total length of .Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

of an impending attack, they were shot as enemy agents. Some historians believe that Stalin, despite providing an amicable front to Hitler, did not wish to remain allies with Germany. Rather, Stalin might have had intentions to break off from Germany and proceed with his own campaign against Germany to be followed by one against the rest of Europe. Other historians contend that Stalin did not plan for such an attack in June 1941, given the parlous state of the Red Army at the time of the invasion.

Axis invasion plans

Stalin's reputation as a brutal dictator contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their expectations of success, as Stalin's

Stalin's reputation as a brutal dictator contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their expectations of success, as Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

of the 1930s had executed many competent and experienced military officers, leaving Red Army leadership weaker than their German adversary. The Nazis often emphasized the Soviet regime's brutality when targeting the Slavs with propaganda. They also claimed that the Red Army was preparing to attack the Germans, and their own invasion was thus presented as a pre-emptive strike.

Hitler also utilised the rising tension between the Soviet Union and Germany over territories in the Balkans as one of the pretexts for the invasion. While no concrete plans had yet been made, Hitler told one of his generals in June 1940 that the victories in Western Europe finally freed his hands for a "final showdown" with Bolshevism. With the successful end to the campaign in France, General Erich Marcks

Erich Marcks (6 June 1891 – 12 June 1944) was a German general in the Wehrmacht during World War II. He authored the first draft of the operational plan, ''Operation Draft East'', for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, adv ...

was assigned the task of drawing up the initial invasion plans of the Soviet Union. The first battle plans were entitled ''Operation Draft East'' (colloquially known as the ''Marcks Plan''). His report advocated the A-A line

The Arkhangelsk–Astrakhan line, or A–A line for short, was the military goal of Operation Barbarossa. It is also known as the Volga–Arkhangelsk line, as well as (more rarely) the Volga–Arkhangelsk–Astrakhan line. It was first mentioned ...

as the operational objective of any invasion of the Soviet Union. This assault would extend from the northern city of Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the ...

on the Arctic Sea

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

through Gorky and Rostov

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

to the port city of Astrakhan

Astrakhan (, ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the Caspian Depression, from the Caspian Se ...

at the mouth of the Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

on the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

. The report concluded that—once established—this military border would reduce the threat to Germany from attacks by enemy bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strategic bombing is ...

.

Although Hitler was warned by many high-ranking military officers, such as Friedrich Paulus

Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst Paulus (23 September 1890 – 1 February 1957) was a German ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) during World War II who is best known for his surrender of the German 6th Army (Wehrmacht), 6th Army during the Battle ...

, that occupying Western Russia would create "more of a drain than a relief for Germany's economic situation," he anticipated compensatory benefits such as the demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milita ...

of entire divisions to relieve the acute labour shortage

In economics, a shortage or excess demand is a situation in which the demand for a product or service exceeds its supply in a market. It is the opposite of an excess supply ( surplus).

Definitions

In a perfect market (one that matches a s ...

in German industry, the exploitation of Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

as a reliable and immense source of agricultural products, the use of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

to stimulate Germany's overall economy and the expansion of territory to improve Germany's efforts to isolate the United Kingdom. Hitler was further convinced that Britain would sue for peace once the Germans triumphed in the Soviet Union, and if they did not, he would use the resources gained in the East to defeat the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

.

Hitler received the final military plans for the invasion on 5 December 1940, which the German High Command had been working on since July 1940, under the codename "Operation Otto." Upon reviewing the plans, Hitler formally committed Germany to the invasion when he issued ''Führer Directive 21'' on 18 December 1940, where he outlined the precise manner in which the operation was to be carried out. Hitler also renamed the operation to ''Barbarossa'' in honor of medieval Emperor Friedrich I of the Holy Roman Empire, a leader of the Third Crusade in the 12th century. The Barbarossa Decree

The Military Justice Decree (), commonly known as the Barbarossa decree, was one of the criminal orders of the ''Wehrmacht'' issued by ''Generalfeldmarschall'' Wilhelm Keitel on 13 May 1941. The decree declared that the upcoming Operation Barbaro ...

, issued by Hitler on 30 March 1941, supplemented the Directive by decreeing that the war against the Soviet Union would be one of annihilation and legally sanctioned the eradication of all Communist political leaders and intellectual elites in Eastern Europe. The invasion was tentatively set for May 1941.

According to a 1978 essay by German historian Andreas Hillgruber

Andreas Fritz Hillgruber (18 January 1925 – 8 May 1989) was a Conservatism, conservative German historian who was influential as a military and diplomatic historian who played a leading role in the ''Historikerstreit'' of the 1980s. In his contr ...

, the invasion plans drawn up by the German military elite were substantially coloured by hubris, stemming from the rapid defeat of France at the hands of the "invincible" ''Wehrmacht'' and by traditional German stereotypes of Russia as a primitive, backward "Asiatic" country. Red Army soldiers were considered brave and tough, but the officer corps was held in contempt. The leadership of the ''Wehrmacht'' paid little attention to politics, culture, and the considerable industrial capacity of the Soviet Union, in favour of a very narrow military view. Hillgruber argued that because these assumptions were shared by the entire military elite, Hitler was able to push through with a "war of annihilation" that would be waged in the most inhumane fashion possible with the complicity of "several military leaders," even though it was quite clear that this would be in violation of all accepted norms of warfare.

Even so, in autumn 1940, some high-ranking German military officials drafted a memorandum to Hitler on the dangers of an invasion of the Soviet Union. They argued that the eastern territories (Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, Byelorussian SSR or Byelorussia; ; ), also known as Soviet Belarus or simply Belarus, was a Republics of the Soviet Union, republic of the Soviet Union (USSR). It existed between 1920 and 19 ...

, the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, (abbreviated Estonian SSR, Soviet Estonia, or simply Estonia ) was an administrative subunit (Republics of the Soviet Union, union republic) of the former Soviet Union (USSR), covering the Occupation o ...

, the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic (Also known as the Latvian SSR, or Latvia) was a constituent republic of the Soviet Union from 1940 to 1941, and then from 1944 until 1990.

The Soviet occupation and annexation of Latvia began between J ...

, and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; ; ), also known as Soviet Lithuania or simply Lithuania, was ''de facto'' one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union between 1940–1941 and 1944 ...

) would only end up as a further economic burden for Germany. It was further argued that the Soviets, in their current bureaucratic form, were harmless and that the occupation would not benefit Germany politically either. Hitler, solely focused on his ultimate ideological goal of eliminating the Soviet Union and Communism, disagreed with economists about the risks and told his right-hand man Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, the chief of the ''Luftwaffe'', that he would no longer listen to misgivings about the economic dangers of a war with the USSR. It is speculated that this was passed on to General Georg Thomas

Georg Thomas (20 February 1890 – 29 December 1946) was a German general who served during World War II.Mitcham and Mueller, ''Hitler's Commanders'', pgs. 17-20. He was a leading participant in planning and carrying out economic exploitation of ...

, who had produced reports that predicted a net economic drain for Germany in the event of an invasion of the Soviet Union unless its economy was captured intact and the Caucasus oilfields seized in the first blow; Thomas revised his future report to fit Hitler's wishes. The Red Army's ineptitude in the Winter War

The Winter War was a war between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peac ...

against Finland in 1939–40 also convinced Hitler of a quick victory within a few months. Neither Hitler nor the General Staff anticipated a long campaign lasting into the winter and therefore, adequate preparations such as the distribution of warm clothing and winterisation

Winterization is the process of preparing something for the winter, and is a form of ruggedization.

Equipment suitable for year-round use can be said to have "built-in" winterization.

Humanitarian aid

In emergency or disaster response situati ...

of important military equipment like tanks and artillery, were not made.

Further to Hitler's Directive, Göring's Green Folder

The "Green Folder" () was a document belonging to ''Reichsmarschall'' Hermann Göring which was presented in the Nuremberg Trials. This was the master policy directive for the economic exploitation of the conquered Soviet Union. The implication ...

, issued in March 1941, laid out the agenda for the next step after the anticipated quick conquest of the Soviet Union. The Hunger Plan

The Hunger Plan () was a partially implemented plan developed by Nazi Germany, Nazi bureaucrats during World War II to seize food from the Soviet Union and give it to German soldiers and civilians. The plan entailed the genocide by Starvation (cri ...

outlined how entire urban populations of conquered territories were to be starved to death, thus creating an agricultural surplus to feed Germany and urban space for the German upper class. This genocidal strategy aimed to redirect agricultural resources from the Soviet Union to Germany by cutting off food to vast regions—particularly central and northern Russia—resulting in the intentional starvation of millions. These policies were modified by late 1941 when the original plan proved logistically untenable. Nevertheless, the strategy of feeding only those civilians deemed economically useful continued, leading to mass deaths in urban centres like Leningrad, Kharkiv, and Kiev.

To this end, Nazi policy aimed to destroy the Soviet Union as a political entity in accordance with the geopolitical

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: ''de facto'' independen ...

ideals for the benefit of future generations of the "Nordic

Nordic most commonly refers to:

* Nordic countries, the northern European countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and their North Atlantic territories

* Scandinavia, a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern ...

master race

The master race ( ) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology, in which the putative Aryan race is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as ''master humans'' ( ).

The Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg b ...

". In 1941, Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

—later appointed Reich Minister of the Occupied Eastern Territories—suggested that conquered Soviet territory should be administered in the following ('Reich Commissionerships'):

German military planners also researched Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia. In their calculations, they concluded that there was little danger of a large-scale retreat of the Red Army into the Russian interior, as it could not afford to give up the Baltic countries, Ukraine, or the Moscow and Leningrad regions, all of which were vital to the Red Army for supply reasons and would thus, have to be defended. Hitler and his generals disagreed on where Germany should focus its energy. Hitler, in many discussions with his generals, repeated his order of "Leningrad first, the Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

second, Moscow third;" but he consistently emphasized the destruction of the Red Army over the achievement of specific terrain objectives. Hitler believed Moscow to be of "no great importance" in the defeat of the Soviet Union and instead believed victory would come with the destruction of the Red Army west of the capital, especially west of the Western Dvina

The Daugava ( ), also known as the Western Dvina or the Väina River, is a large river rising in the Valdai Hills of Russia that flows through Belarus and Latvia into the Gulf of Riga of the Baltic Sea. The Daugava rises close to the source of t ...

and Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

rivers, and this pervaded the plan for Barbarossa. This belief later led to disputes between Hitler and several German senior officers, including Heinz Guderian