1570 Ferrara Earthquake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1570 Ferrara earthquake struck the Italian city of

The

The

In 1570 the city was held by Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara,

In 1570 the city was held by Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara,

Page on the 1570 Ferrara earthquake

from the CFTI5 Catalogue of Strong Earthquakes in Italy (461 BC – 1997) and Mediterranean Area (760 B.C. – 1500) Guidoboni E., Ferrari G., Mariotti D., Comastri A., Tarabusi G., Sgattoni G., Valensise G. (2018) (''in Italian'') {{Earthquakes in Italy 1570 Ferrara Ferrara earthquake Ferrara earthquake Ferrara earthquake 1570 in science History of Ferrara

Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

on November 16 and 17, 1570. After the initial shocks, a sequence of aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousand ...

s continued for four years, with over 2,000 in the period from November 1570 to February 1571.

The same area was struck, centuries later, by another major earthquake of comparable intensity.

The disaster destroyed half the city, permanently marked many of the buildings left standing, and directly contributed to – but was not the sole cause of – a long-term decline of the city lasting until the 19th century.

The earthquake caused the first documented episode of soil liquefaction

Soil liquefaction occurs when a cohesionless saturated or partially saturated soil substantially loses strength and stiffness in response to an applied stress such as shaking during an earthquake or other sudden change in stress condition, ...

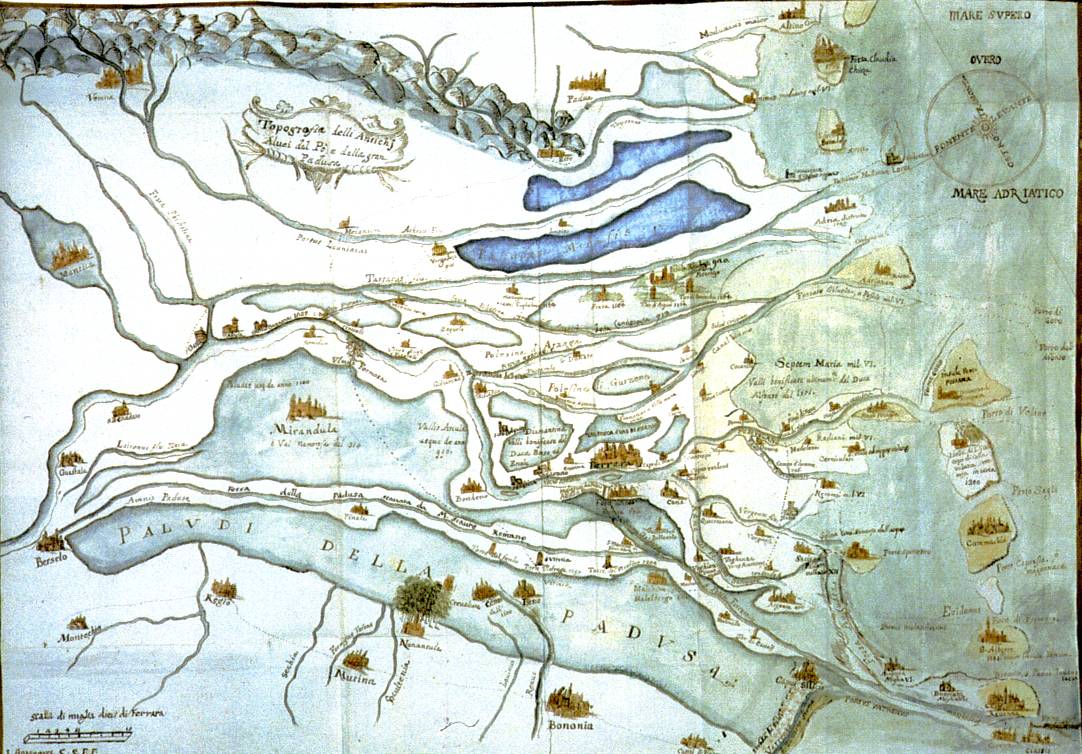

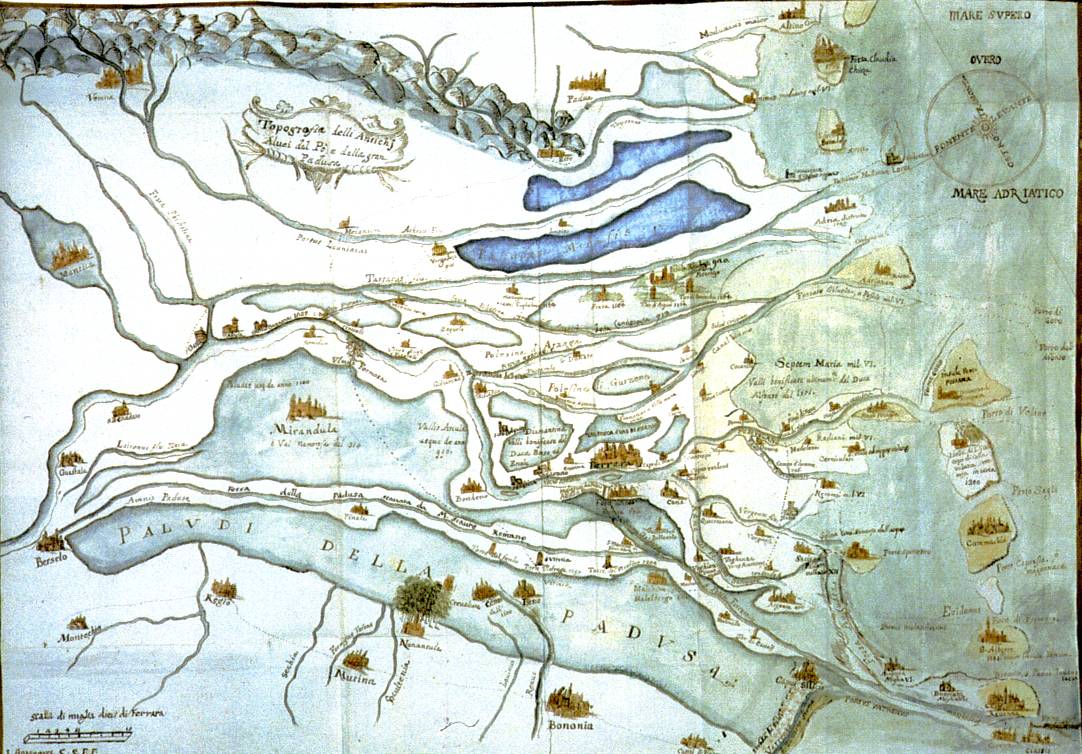

in the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic e ...

, and one of the oldest occurrences of the event known outside of paleoseismology. It led to the establishment of an earthquake observatory which published to very high regard, and the drafting of some of the first-known building designs based on a scientific seismic-resistant approach.

Geology

The

The Po Plain

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic e ...

, which is a foreland basin

A foreland basin is a structural basin that develops adjacent and parallel to a mountain belt. Foreland basins form because the immense mass created by crustal thickening associated with the evolution of a mountain belt causes the lithosphere ...

formed by the of the crust by the loading of the Apennine thrust sheets, overlies and mainly conceals the active front of the Northern Apennines fold and thrust belt

A fold and thrust belt (FTB) is a series of mountainous foothills adjacent to an orogenic belt, which forms due to contractional tectonics. Fold and thrust belts commonly form in the forelands adjacent to major orogens as deformation propagates ...

, across which there is about 1 mm per year of active shortening at present. Information from hydrocarbon exploration

Hydrocarbon exploration (or oil and gas exploration) is the search by petroleum geologists and geophysicists for deposits of hydrocarbons, particularly petroleum and natural gas, in the Earth using petroleum geology.

Exploration methods

Vi ...

demonstrates that the area is underlain by a series of active thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s and related folds

Benjamin Scott Folds (born September 12, 1966) is an American singer-songwriter, musician, and composer, who is the first artistic advisor to the National Symphony Orchestra at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Kennedy Center in ...

, some of which have been detected from anomalous drainage patterns. These blind thrust faults are roughly west-northwest–east-southeast-trending, parallel to the mountain front, and dip shallowly towards the south-southwest. The 1570 earthquake has been linked to movement on the outermost and northernmost of these thrusts.

Ferrara

The city

Ferrara is located on the Emilian side of thePo Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic e ...

, an alluvial plain

An alluvial plain is a largely flat landform created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms. A floodplain is part of the process, being the s ...

geologically quite stable since the Messinian

The Messinian is in the geologic timescale the last age or uppermost stage of the Miocene. It spans the time between 7.246 ± 0.005 Ma and 5.333 ± 0.005 Ma (million years ago). It follows the Tortonian and is followed by the Zanclean, the fir ...

age (7-5 mya). Small earthquakes are common, albeit not frequent, but rarely lead to considerable damage to the urban cityscape. Ferrara was the location for minor earthquakes in the four centuries before 1570, these events being recorded in the city archives with detailed descriptions of damage to buildings and depositions by witnesses.

At the time of the 1570 event, it was a medium-sized city, with 32,000 inhabitants.

Despite continuous – and often victorious – wars against the age's superpowers, the nearby Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

, Ferrara in the 16th century was a thriving city, a major hub for trade, business and liberal arts. World class music and painting schools, linked with Flemish artistic communities, were established in the late 15th and early 16th century, under the patronage of the House of Este. Musical instrument workshops, and especially the making of lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can re ...

s, were a pride of the city and were considered preeminent.

A new part of the city, named Addizione Erculea (''Erculean Addition'') had been built in the previous century: it is commonly considered one of the major examples of urban planning in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, the biggest and most architecturally advanced town expansion project in Europe at the time.

Political, economical and religious situation

In 1570 the city was held by Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara,

In 1570 the city was held by Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. ...

of Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

, a beloved ruler and a devoted liberal art patron, but careless and a big spender as an administrator. Alfonso was the main sponsor of many artists including Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' ( Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...

, Giovanni Battista Guarini

Giovanni Battista Guarini (10 December 1538 – 7 October 1612) was an Italian poet, dramatist, and diplomat.

Life

Guarini was born in Ferrara. On the termination of his studies at the universities of Pisa, Padua and Ferrara, he was appointed pr ...

, Luzzasco Luzzaschi and Cesare Cremonini, confirming the reputation of Ferrara as a haven for artists and freethinkers. The emerging of the city as a cultural powerhouse came at the cost of a sharp increase in taxes.

The city was a safe refuge for Jews and converts from the persistent prosecutions promoted by the Roman Catholic Church. Despite Alfonso II's formal status as a vassal of the Holy Seat, he never took any action against the two thousand Jews living in the city walls, well knowing that the Hebrew community accounted for a strong share of the city cultural and economic success. His disregard of the Holy Seat's orders made him more than one enemy.

Even if he was walking on a thin line, Alfonso managed to avoid the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's many diplomatic and legal challenges to the city independence, thanks to cunning politics and a strong friendship with the powerful Charles IX of France

Charles IX (Charles Maximilien; 27 June 1550 – 30 May 1574) was King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He ascended the French throne upon the death of his brother Francis II in 1560, and as such was the penultimate monarch of the ...

. It is to be remembered that Alfonso II was the son of Renée of France

Renée of France (25 October 1510 – 12 June 1574), was Duchess of Ferrara from 31 October 1534 until 3 October 1559 by marriage to Ercole II d'Este, grandson of Pope Alexander VI. She was the younger surviving child of Louis XII of France a ...

, member of the House of Valois

The Capetian house of Valois ( , also , ) was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. They succeeded the House of Capet (or "Direct Capetians") to the French throne, and were the royal house of France from 1328 to 1589. Junior members of the ...

, declared heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and guilty of housing John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

himself under the eyes of the Catholics.

Alfonso was not new to compromises: to smooth his frequent brushes with the Pope, he was usually attending masses and acting as a good Catholic in public, receiving communion

Communion may refer to:

Religion

* The Eucharist (also called the Holy Communion or Lord's Supper), the Christian rite involving the eating of bread and drinking of wine, reenacting the Last Supper

**Communion (chant), the Gregorian chant that ac ...

, giving substantial sums to charity, arranging religious parades for saints and building convents.

Both the high taxation, and the soft stance with the Jews ultimately gained him hostility in the most die-hard Catholic part of the population, which supported an acquisition of the city and its lands by the Holy Seat. Those rebel fringes were instrumental in the political struggle following the disaster.

The earthquake

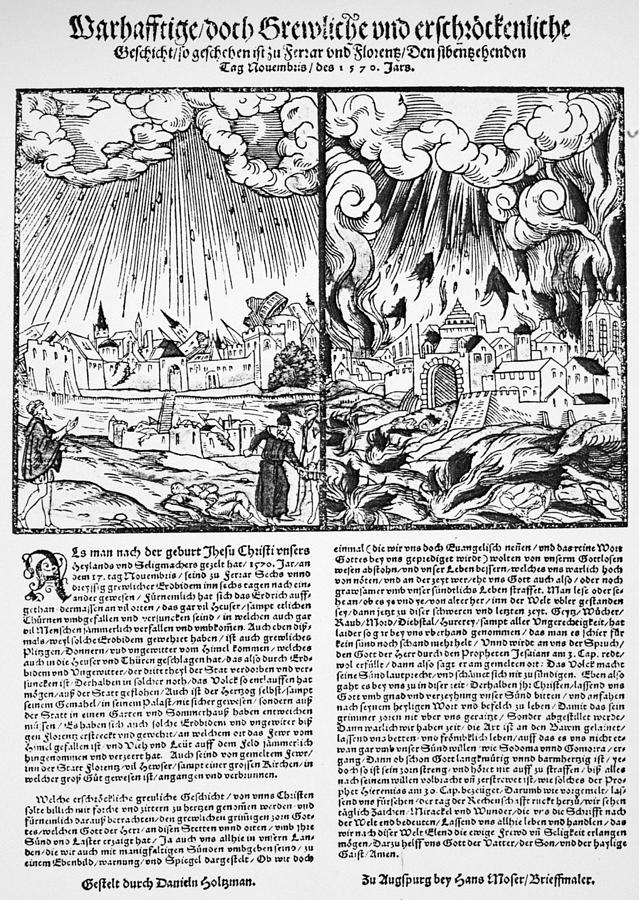

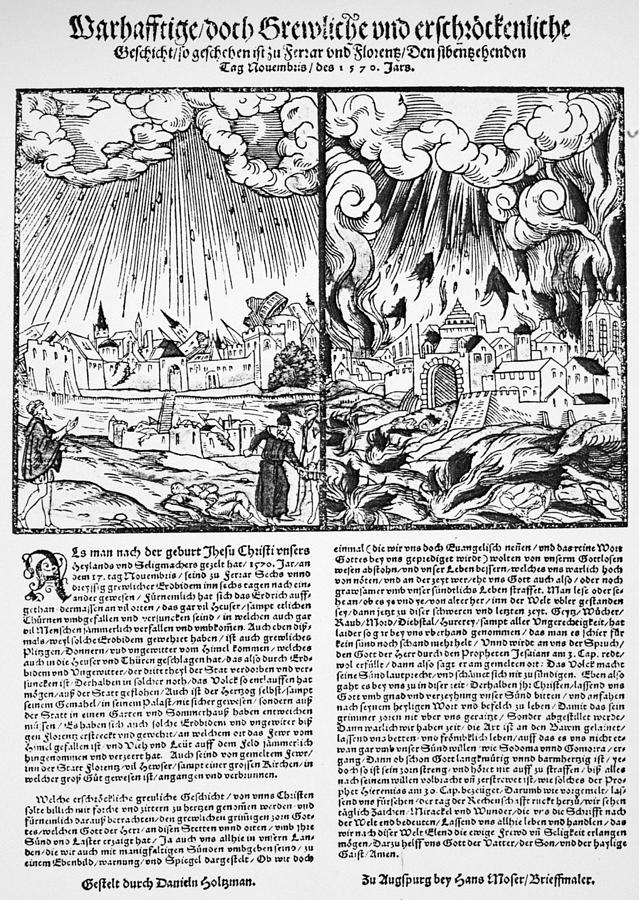

Precursor events and main shock

Earthquake lights were seen above the city on November 15, 1570, the night before the first quake. Flames were reported to come out from the soil and raise into the air, probably small pockets of natural gas set free by cracks in the earth crust. The earthquake struck at dawn: three strong shocks hit the city in the first day; one – the strongest – the day after. The first strong shock struck at 9.30 (local time) November 16, 1570, its epicenter just a few kilometers under the city centre. Six hundred pieces of stone masonry (mostly battlements, balconies and chimneys) are reported to have fallen, further damaging the flimsy stone andhay

Hay is grass, legumes, or other herbaceous plants that have been cut and dried to be stored for use as animal fodder, either for large grazing animals raised as livestock, such as cattle, horses, goats, and sheep, or for smaller domesticate ...

roofs. The following day the ground trembled again many times. At 8 pm a new powerful shock caused severe damage to walls and caused some buildings to sustain structural damage. Just four hours later, a new tremor caused new cracks and some collapse. At 3 am on November 17 the ground shook harder than ever; many buildings, damaged by the previous shocks, gave way and caved in.

Many churches' facades, often built as self-standing walls rising well over the effective architecture, collapsed, including at the Duomo

''Duomo'' (, ) is an Italian term for a church with the features of, or having been built to serve as, a cathedral, whether or not it currently plays this role. Monza Cathedral, for example, has never been a diocesan seat and is by definition n ...

.

Forty percent of the city buildings were damaged, including almost every public building. Some of them collapsed, and many churches sustained critical damage to pillars and main walls. Observers reported that the shallow bowl-shaped valley where Ferrara lies seemed to rise into a kind of hump, before coming back to its original profile. Damage to the city were assessed in over 300,000 scudi

The ''scudo'' (pl. ''scudi'') was the name for a number of coins used in various states in the Italian peninsula until the 19th century. The name, like that of the French écu and the Spanish and Portuguese escudo, was derived from the Latin '' ...

, a huge sum at the time. The event was a surprise to many scholars, since according to the then mainstream theory of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

, earthquakes were not meant to strike in winter or on flat land.

Minor earthquakes had struck Ferrara in the past (events were recorded in 1222, 1504, 1511 and 1561, some of them causing little damage, and a stronger event in 1346). The exceptional length of the seismic swarm, unprecedented at the time in Ferrara, led some to believe it was a supernatural phenomenon.

The earthquake's intensity has been assessed as VIII on the Mercalli intensity scale

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM, MMI, or MCS), developed from Giuseppe Mercalli's Mercalli intensity scale of 1902, is a seismic intensity scale used for measuring the intensity of shaking produced by an earthquake. It measures the effe ...

: only the 1346 event was similar in intensity, though minor urbanization led to less evident damage (but more victims), the other have been all marked as class VII or VI. Other seismic events would hit the city in 1695, 1787 (three shocks in ten days) and 1796.

Initial damage evaluation

Palaces and public buildings

Castello Estense

The ' (‘Este castle’) or ' (‘St. Michael's castle’) is a moated medieval castle in the center of Ferrara, northern Italy. It consists of a large block with four corner towers.

History

On 3 May 1385, the Ferrarese people, driven to des ...

, seat of the Duke, received major damage and became unfit for use. The Palazzo della Ragione (town hall) partially collapsed, as did the enclosure walls of both Loggia dei Banchieri and Loggia dei Callegari, in front of the Dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a ...

. Palazzo Vescovile (the Bishop's Palace) was destroyed, and had to be rebuilt. Minor damage was inflicted on the Cardinal Palace, Palazzo del Paradiso, Palazzo Tassoni and Duke Alfonso's personal palace.

Churches

Damage to churches was widespread.San Paolo

San Paolo ( Italian for "Saint Paul") is a ''comune'' in the Province of Brescia

The Province of Brescia ( it, provincia di Brescia; Brescian: ) is a Province in the Lombardy administrative region of northern Italy. It has a population of s ...

and S. Giovanni Battista churches collapsed, many paintings with them. Facades of S.Francesco, S.Andrea, Santa Maria in Vado

Santa Maria in Vado is a church located on Via Borgovado number 3 in Ferrara, Region of Emilia-Romagna, Italy.

History

The church derives its name from a guado or fording (''vado'' in dialect) that was located nearby. A church at the site was do ...

, S.Domenico, and Santa Maria della Consolazione churches were severely damaged or destroyed, as was the Charterhouse's. The Santa Maria degli Angeli church, still under constructions, was so severely damaged that further work was abandoned. Other than the facade, the Duomo lost the Corpus Domini chapel and part of a side wing: the heavy iron chain above the main altar fell to the ground, along with the columns' fine marble capitals. San Paolo church had to be rebuilt from scratch.

Towers

Manytower

A tower is a tall structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting structures.

Towers are specifi ...

s, a common kind of architecture in the Italian city skyline in the renaissance, were damaged. The Castle's bell tower collapsed to the ground, as did the top portion of the other three major towers of the town: Palazzo della Ragione's, the Porta S. Pietro donjon

A keep (from the Middle English ''kype'') is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in ...

and Castel Tealdo tower. The Steeple

In architecture, a steeple is a tall tower on a building, topped by a spire and often incorporating a belfry and other components. Steeples are very common on Christian churches and cathedrals and the use of the term generally connotes a relig ...

s of the Duomo, of S.Silvestro, S.Agostino, S.Giorgio and S.Bartolo churches were severely damaged.

Further shocks

The seismic wave kept going for four years, but the worst was over after about six months. Just one month after the earthquake, on December 15, 1570 a new powerful shock hit the city: this time the battered Palazzo Tassoni, S.Andrea church and S.Agostino church were not spared. On the following January 12, 1571 a new shock damaged Palazzo Montecuccoli.Victims

Despite the widespread damage, fatalities were quite limited. The initial shocks alerted the population, and gave them time to evacuate the damaged buildings. The majority of houses were of one or two story height, and received less severe damage than the grander palaces and churches. Reliable sources, such as historian Cesare Nubilonio, estimate 40 victims, whileAzariah dei Rossi

Azariah ben Moses dei Rossi ( Hebrew: עזריה מן האדומים) was an Italian-Jewish physician and scholar. He was born at Mantua in 1511; and died in 1578. He was descended from an old Jewish family which, according to a tradition, wa ...

and Giovanni Battista Guarini

Giovanni Battista Guarini (10 December 1538 – 7 October 1612) was an Italian poet, dramatist, and diplomat.

Life

Guarini was born in Ferrara. On the termination of his studies at the universities of Pisa, Padua and Ferrara, he was appointed pr ...

both place the estimate at 70. Other sources vary from 9 dead to over 100, with some other occurrences of estimates of the order of two hundred or five hundred, usually taken as unreliable. Florence's ambassador Canigiani is known to have written home about 130 to 150 victims.

City evacuation

The poor and the wealthy

People were scared by the disaster and about a third of the populace left the city for good. City jails collapsed and prisoners escaped the rubble, leading to a crime spree in the city and countryside. The palaces of the notables and courtesans were damaged as well as the poorest mansions, and the whole city population had to seek shelter together in tents and refuges, despite their status or wealth. Contemporary account estimate eleven thousand people left the city. The townspeople remained refugees for the following two years, due to the aftershocks. The resulting situation, in which societal rules were upset or fell in disuse, was perceived as awkward and unnatural by both peasants and well-to-do, leading to common psychological issues amongst the population. Along with the fear of aftershocks, people developed a sense of impending doom, precariousness and a general mistrust in humanity.The country court

Duke Alfonso II d'Este and his family barely escaped the collapse of a tower of Castello Estense. The lord fled the city by coach, and set up a temporary court in the fields of the San Benedetto garden near the city along with his closest advisor. This unusual improvisation was not well regarded by the Pope and was seen as demeaning by other rulers, but ultimately it proved to be a wise choice and a necessity in view of the duration of the aftershocks. Ferrara's fate appeared sealed to the ambassadors visiting the refugee Duke: in correspondence between the embassies and the nobles, the region is sometimes called "di Val di Po dov'era Ferrara" (''Po Valley, where Ferrara once stood''). Florence's ambassadors were especially skeptical about the chances of city recovery.Political struggle about the rebuilding

The Pope's stance

The Duke asked Pope Pius V for help, or at least a public blessing to the city: he receiving nothing but a firm reprimand for not having prosecuted enough the city's Jews, well deserving God's wrath toward the city. Alfonso II's answer was prompt, pointing out the evident natural cause of the disaster and discharging any allegation about blaming the Jews. The Pope's rebuttal was a blunt political maneuver, meant to undermine Alfonso's authority by exploiting the discontented minorities: it stated that since the city administration tolerated the presence of the assassins of Jesus Christ, then God was justifiably angry toward the whole city. Full blame was to be put on Alfonso's part, not on the Jews, for failing to expel them from the city walls. Jewish city scholarAzariah dei Rossi

Azariah ben Moses dei Rossi ( Hebrew: עזריה מן האדומים) was an Italian-Jewish physician and scholar. He was born at Mantua in 1511; and died in 1578. He was descended from an old Jewish family which, according to a tradition, wa ...

wrote a short essay on the earthquake in the following days, named ''Kol Elohim'': in the account, he credited the earthquake to a visit from God himself, suggesting it was a supernatural event but not implying any punishment toward the city or its Jews.

Scaring the population

Along with the Pope's stern letter, emissaries from theCapuchins

Capuchin can refer to:

*Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, an order of Roman Catholic friars

*Capuchin Poor Clares, an order of Roman Catholic contemplative religious sisters

*Capuchin monkey, primates of the genus ''Cebus'' and ''Sapajus'', named af ...

were sent to the town from Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, in order to scare the populace and turn it against Alfonso. The friars took some decomposing corpses from the rubble, and brought them in procession claiming that God was going to sink the city to hell if the people refused to drive Alfonso away.

The macabre show further contributed to the widespread sense of doom and distrust: people living in one of the most free and culturally lively cities of Italy suddenly was cast into a gloomy atmosphere of superstition and religious obscurantism.

The Duke's reaction

Bothered by the Capuchins' show, annoyed by the Pope's political maneuvers and worried about the loss of hope of the citizens, the Duke decided to display his strength by forcibly expelling the rabble-rousing friars from the city, abandoning any expectation of papal help and unilaterally taking in his hands the control of the city rebuilding. He walked in procession through the debris, followed by his most trustworthy men, to show off to the populace his control on the city, its laws and its people. The Duke made every effort to have theCastello Estense

The ' (‘Este castle’) or ' (‘St. Michael's castle’) is a moated medieval castle in the center of Ferrara, northern Italy. It consists of a large block with four corner towers.

History

On 3 May 1385, the Ferrarese people, driven to des ...

repaired in record time, to downplay his hardnesses with the other Italian rulers and to begin to restore a sense of normality in the evacuees. Relationships with the Papacy remained strained, but Alfonso always managed to keep the Pope's demands and attacks at bay.

Return into the city and rebuilding efforts

After Castello Estense was made safe again, thanks to many iron rods and anchors, in March 1571 the Duke triumphantly relocated back to the city and the return to normality begun to look possible. Minor shocks kept coming, but the city was ready for rebuilding. Immediately Duke Alfonso ordered a census of the remaining population, and on August 14, 1571 issued a decree ordering the ''Ferraresi'' to come back to the city. Return was mandatory for people living in the city for at least 15 years (that is, people with full citizenship rights), under penalty of seizing of their estates. Despite the order, only about two out of three came back to the city: among the people who left the city were many of the wealthiest and a good portion of the court nobles – further diminishing the prestige of Alfonso II. At first rebuilding works begun on the Duomo and on S.Michele, S.Romano andSanta Maria in Vado

Santa Maria in Vado is a church located on Via Borgovado number 3 in Ferrara, Region of Emilia-Romagna, Italy.

History

The church derives its name from a guado or fording (''vado'' in dialect) that was located nearby. A church at the site was do ...

churches, overseen by Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, ...

Maremonti. According to Guarini, works on S.Rocco, S.Silvestro, S.Stefano, S.Cristoforo, S.Francesco and the rebuilding of S.Paolo begun shortly after, the latter being completed in 1575.

Damage to buildings was so widespread – chronicles reports that all the public building and most of the houses needed work – that the forging of the much needed iron bars caused a shortage of metal in the whole province, depleting stockpiles and requiring massive imports from nearby cities.

The earthquake observatory

Founding of the observatory

Alfonso called on his court scholars inphysics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, philosophers and many "experts in various accidents" to inquire into the causes of the disaster, appointing as their leader the renowned Neapolitan architect Pirro Ligorio

Pirro Ligorio ( October 30, 1583) was an Italian architect, painter, antiquarian, and garden designer during the Renaissance period. He worked as the Vatican's Papal Architect under Popes Paul IV and Pius IV, designed the fountains at Villa d� ...

(a successor of Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

as head of the San Pietro in Vaticano workshop), effectively founding the first seismological observatory and think tank on earthquakes in the world.

The study group wrote six treatises in the following year: four of them were published and quickly became regarded as masterpieces among that part of natural philosophy dedicated to the study of earthquakes, their reputation lasting through the following two centuries. The essays were essential in disproving emerging theories that blamed the earthquake on the drainage of the many Duchy's swamps and their reclamation as fertile agricultural lands. One of the leading theories at the time was that earthquakes were caused by subterranean winds, excited by change in temperature. The winds should have escaped through the marshes, but drainage compromised the process so the winds grew in pressure and caused shocks.

Ligorio's work on building safety

Pirro Ligorio

Pirro Ligorio ( October 30, 1583) was an Italian architect, painter, antiquarian, and garden designer during the Renaissance period. He worked as the Vatican's Papal Architect under Popes Paul IV and Pius IV, designed the fountains at Villa d� ...

was a scientist and a devout catholic: he needed to carefully weigh his words to avoid a clash with the Curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

while at the same time proving that the Pope's claims were unfounded. He collected a long list of earthquakes of the past, compiling a time-line and showing how they were a common and natural occurrence in many parts of the known world. He kept a diary of the aftershock, writing in abundance of detail about their intensity and the damage they kept doing to the city, dramatically improving knowledge of shocks dynamics and consequences of an earthquake.

Ultimately, Ligorio put the blame for the extensive damage on inappropriate techniques and bad materials used in building the city's edifices. The random mixing of stones, brick and sand in the main walls was strongly criticized, along with the rooftops built to push horizontally on the side walls (instead of providing a vertical load). Approximation in leveling of walls and ceilings led to uneven discharge of forces.

In the last part of his treatise, ''Rimedi contra terremoti per la sicurezza degli edifici'' (Remedies against earthquakes for building security), Ligorio presented design plans for a shock-proof building, the first known design with a scientific anti-seismic approach. Many of the empirical findings of Ligorio are consistent with contemporary anti-seismic practices: among them the correct dimensioning of main walls, use of better and stronger bricks as well as elastic structural joints and iron rods.

Following years

Loss of independence

Late in 1571, Alfonso II was called to fight against theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

fleet in the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Sovere ...

. While the Duke was away, the Pope executed a thorough purge of the Jews from the Papal States, including Ferrara. The only allowed ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

es were established in Rome and Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

. Pope Pius V died the following year.

After the earthquake, many nobles and well-off merchants left the city, managing their business in their country villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

s or moving their houses to nearby towns. Ferrara lost its capital city status and was demoted to a simple border city squeezed between Venice and the Papal States, never fully achieving economic recovery from the disaster. Without the Jews' businesses, crushed by costly reconstruction debts and losing its thriving cultural circle, the city became a minor trade and agricultural hub up until the 19th century.

In 1598, Alfonso died without legitimate heirs, and the city was formally annexed to the Papal States by means of questionable claims of vacancy. The annexation of Ferrara and Comacchio Comacchio (; egl, label= Comacchiese, Cmâc' ) is a town and ''comune'' of Emilia Romagna, Italy, in the province of Ferrara, from the provincial capital Ferrara. It was founded about two thousand years ago; across its history it was first gove ...

was disputed by many contemporaries, including the weak Duke of Modena

Modena (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language#Dialects, Modenese, Mòdna ; ett, Mutna; la, Mutina) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern I ...

Cesare d'Este who was the direct candidate to the succession, but was ultimately completed.

Permanent damage

The city's architecture still bears many marks from the earthquake. Iron braces and rods placed in the aftermath of the shocks to strengthen the damaged walls are still present, windows closed with stones and concrete to improve the stability of damaged facades are a common occurrence and there are traces of the stubs once sustaining collapsed balconies and porches. Chimneys, decoratedbattlement

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at inter ...

s and terrace

Terrace may refer to:

Landforms and construction

* Fluvial terrace, a natural, flat surface that borders and lies above the floodplain of a stream or river

* Terrace, a street suffix

* Terrace, the portion of a lot between the public sidewalk an ...

s were damaged or destroyed, and were rebuilt in the following decade in a changed style and materials.

Walls from historical buildings are often uneven and out of angle. This is sometimes said by locals to provoke the special Ferrara feeling to visitors, a veiled sense of dizziness and disorientation.

See also

*List of earthquakes in Italy

This is a list of earthquakes in Italy that had epicentres in Italy, or significantly affected the country. The highest seismicity hazard in Italy was concentrated in the central-southern part of the peninsula, along the Apennine ridge, in Cala ...

*List of historical earthquakes

Historical earthquakes is a list of significant earthquakes known to have occurred prior to the beginning of the 20th century. As the events listed here occurred before routine instrumental recordings, they rely mainly on the analysis of writte ...

References

External links

Page on the 1570 Ferrara earthquake

from the CFTI5 Catalogue of Strong Earthquakes in Italy (461 BC – 1997) and Mediterranean Area (760 B.C. – 1500) Guidoboni E., Ferrari G., Mariotti D., Comastri A., Tarabusi G., Sgattoni G., Valensise G. (2018) (''in Italian'') {{Earthquakes in Italy 1570 Ferrara Ferrara earthquake Ferrara earthquake Ferrara earthquake 1570 in science History of Ferrara