|

Telluromethionine

Telluromethionine (sometimes shortened to TeMet) is a rare and natural amino acid. It is a heavy analog of methionine and selenomethionine containing tellurium. Telluromethionine has been suggested as a probe for structural biochemistry, as it can be incorporated into proteins and used for X-ray crystallography and NMR measurements. In aqueous solutions, telluromethioning oxidizes to a telluroxide, but can be recovered by use of DTT. Telluromethionine is not very stable in wheat germ extract, which impacts its translation rate. In the extract, elemental tellurium seems to form, suggesting a degradation mechanism, but this is not well understood. However, enriching proteins with tellurium in auxotrophic ''E. coli ''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...'' was successf ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tellurium

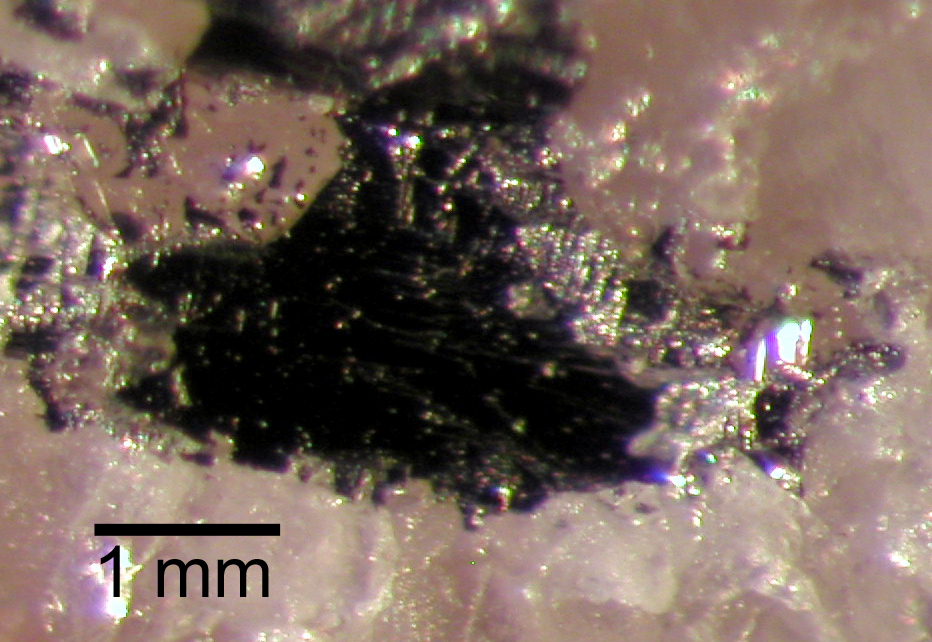

Tellurium is a chemical element with the symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionally found in native form as elemental crystals. Tellurium is far more common in the Universe as a whole than on Earth. Its extreme rarity in the Earth's crust, comparable to that of platinum, is due partly to its formation of a volatile hydride that caused tellurium to be lost to space as a gas during the hot nebular formation of Earth.Anderson, Don L.; "Chemical Composition of the Mantle" in ''Theory of the Earth'', pp. 147-175 Tellurium-bearing compounds were first discovered in 1782 in a gold mine in Kleinschlatten, Transylvania (now Zlatna, Romania) by Austrian mineralogist Franz-Joseph Müller von Reichenstein, although it was Martin Heinrich Klaproth who named the new element in 1798 after the Latin 'earth'. Gold telluride minera ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Amino Acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha amino acids appear in the genetic code. Amino acids can be classified according to the locations of the core structural functional groups, as Alpha and beta carbon, alpha- , beta- , gamma- or delta- amino acids; other categories relate to Chemical polarity, polarity, ionization, and side chain group type (aliphatic, Open-chain compound, acyclic, aromatic, containing hydroxyl or sulfur, etc.). In the form of proteins, amino acid ''residues'' form the second-largest component ( water being the largest) of human muscles and other tissues. Beyond their role as residues in proteins, amino acids participate in a number of processes such as neurotransmitter transport and biosynthesis. It is thought that they played a key role in enabling li ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans. As the precursor of other amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine plays a critical role in the metabolism and health of many species, including humans. It is encoded by the codon AUG. Methionine is also an important part of angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels. Supplementation may benefit those suffering from copper poisoning. Overconsumption of methionine, the methyl group donor in DNA methylation, is related to cancer growth in a number of studies. Methionine was first isolated in 1921 by John Howard Mueller. Biochemical details Methionine (abbreviated as Met or M; encoded by the codon AUG) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological pH conditions), an amino group (which is in the prot ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Selenomethionine

Selenomethionine (SeMet) is a naturally occurring amino acid. The L-selenomethionine enantiomer is the main form of selenium found in Brazil nuts, cereal grains, soybeans, and grassland legumes, while ''Se''-methylselenocysteine, or its γ-glutamyl derivative, is the major form of selenium found in ''Astragalus'', ''Allium'', and ''Brassica'' species. ''In vivo'', selenomethionine is randomly incorporated instead of methionine. Selenomethionine is readily oxidized. Selenomethionine's antioxidant activity arises from its ability to deplete reactive oxygen species. Selenium and methionine also play separate roles in the formation and recycling of glutathione, a key endogenous antioxidant in many organisms, including humans. Substitution chemistry issues Selenium and sulfur are chalcogens that share many chemical properties so the substitution of methionine with selenomethionine may have only a limited effect on protein structure and function. However, the incorporation of sele ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Structural Biochemistry

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as biological organisms, minerals and chemicals. Abstract structures include data structures in computer science and musical form. Types of structure include a hierarchy (a cascade of one-to-many relationships), a network featuring many-to-many links, or a lattice featuring connections between components that are neighbors in space. Load-bearing Buildings, aircraft, skeletons, anthills, beaver dams, bridges and salt domes are all examples of load-bearing structures. The results of construction are divided into buildings and non-building structures, and make up the infrastructure of a human society. Built structures are broadly divided by their varying design approaches and standards, into categories including building structures, a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity. A linear chain of amino acid residues is called a polypeptide. A protein contains at least one long polypeptide. Short polypeptides, containing less than 20–30 residues, are rarely considered to be proteins and are commonly called peptides. The individual amino acid residues are bonded together by peptide bonds and adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acid resid ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles and intensities of these diffracted beams, a crystallographer can produce a three-dimensional picture of the density of electrons within the crystal. From this electron density, the mean positions of the atoms in the crystal can be determined, as well as their chemical bonds, their crystallographic disorder, and various other information. Since many materials can form crystals—such as salts, metals, minerals, semiconductors, as well as various inorganic, organic, and biological molecules—X-ray crystallography has been fundamental in the development of many scientific fields. In its first decades of use, this method determined the size of atoms, the lengths and types of chemical bonds, and the atomic-scale differences among vari ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, most commonly known as NMR spectroscopy or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), is a spectroscopic technique to observe local magnetic fields around atomic nuclei. The sample is placed in a magnetic field and the NMR signal is produced by excitation of the nuclei sample with radio waves into nuclear magnetic resonance, which is detected with sensitive radio receivers. The intramolecular magnetic field around an atom in a molecule changes the resonance frequency, thus giving access to details of the electronic structure of a molecule and its individual functional groups. As the fields are unique or highly characteristic to individual compounds, in modern organic chemistry practice, NMR spectroscopy is the definitive method to identify monomolecular organic compounds. The principle of NMR usually involves three sequential steps: # The alignment (polarization) of the magnetic nuclear spins in an applied, constant magnetic field B0. # The p ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Telluroxide

A telluroxide is a type of organotellurium compound with the formula R2TeO. These compounds are analogous to sulfoxides in some respects. Reflecting the decreased tendency of Te to form multiple bonds, telluroxides exist both the monomer and the polymer, which are favored in solution and the solid state, respectively:Jens Beckmann, Dainis Dakternieks, Andrew Duthie, François Ribot, Markus Schürmann, and Naomi A. Lewcenko "New Insights into the "Structures of Diorganotellurium Oxides. The First Polymeric Diorganotelluroxane p-MeOC6H4)2TeOsub>n" Organometallics, 2003, volume 22, 3257–3261. :(R2TeO)n {{Eqm n R2TeO Telluroxides are prepared from the telluroethers by halogenation In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction that entails the introduction of one or more halogens into a compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polyme ... followed by base hydrolysis: :R2Te + Br2 → ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dithiothreitol

Dithiothreitol (DTT) is the common name for a small-molecule redox reagent also known as Cleland's reagent, after W. Wallace Cleland. DTT's formula is C4H10O2S2 and the chemical structure of one of its enantiomers in its reduced form is shown on the right; its oxidized form is a disulfide bonded 6-membered ring (shown below). The reagent is commonly used in its racemic form, as both enantiomers are reactive. Its name derives from the four-carbon sugar, threose. DTT has an epimeric ('sister') compound, dithioerythritol (DTE). Reducing agent DTT is a reducing agent; once oxidized, it forms a stable six-membered ring with an internal disulfide bond. It has a redox potential of −0.33 V at pH 7. The reduction of a typical disulfide bond proceeds by two sequential thiol-disulfide exchange reactions and is illustrated below. The reduction usually does not stop at the mixed-disulfide species because the second thiol of DTT has a high propensity to close the ring, forming oxidized DTT a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Translation (biology)

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the process in which ribosomes in the cytoplasm or endoplasmic reticulum synthesize proteins after the process of transcription of DNA to RNA in the cell's nucleus. The entire process is called gene expression. In translation, messenger RNA (mRNA) is decoded in a ribosome, outside the nucleus, to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide. The polypeptide later folds into an active protein and performs its functions in the cell. The ribosome facilitates decoding by inducing the binding of complementary tRNA anticodon sequences to mRNA codons. The tRNAs carry specific amino acids that are chained together into a polypeptide as the mRNA passes through and is "read" by the ribosome. Translation proceeds in three phases: # Initiation: The ribosome assembles around the target mRNA. The first tRNA is attached at the start codon. # Elongation: The last tRNA validated by the small ribosomal subunit (''accom ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Auxotrophy

Auxotrophy ( grc, αὐξάνω "to increase"; ''τροφή'' "nourishment") is the inability of an organism to synthesize a particular organic compound required for its growth (as defined by IUPAC). An auxotroph is an organism that displays this characteristic; ''auxotrophic'' is the corresponding adjective. Auxotrophy is the opposite of prototrophy, which is characterized by the ability to synthesize all the compounds needed for growth. Prototrophic cells (also referred to as the 'wild type') are self sufficient producers of all required metabolites (e.g. amino acids, lipids, cofactors), while auxotrophs require to be on medium with the metabolite that they cannot produce. For example saying a cell is methionine auxotrophic means that it would need to be on a medium containing methionine or else it would not be able to replicate. In this example this is because it is unable to produce its own methionine (methionine auxotroph). However, a prototroph or a methionine prototrophic c ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |