|

The First Circle

''In the First Circle'' (; also published as ''The First Circle'') is a novel by Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, released in 1968. A more complete version of the book was published in English in 2009. The novel depicts the lives of the occupants of a sharashka (a research and development bureau made of Gulag inmates) located in the Moscow suburbs. This novel is highly autobiographical. Many of the prisoners ( zeks) are technicians or academics who have been arrested under Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code in Joseph Stalin's purges following the Second World War. Unlike inhabitants of other Gulag labor camps, the sharashka zeks were adequately fed and enjoyed good working conditions; however, if they found disfavor with the authorities, they could be instantly shipped to Siberia. The title is an allusion to Dante's first circle, or limbo of Hell in ''The Divine Comedy'', wherein the philosophers of Greece, and other virtuous pagans, live in a walled green garden. They ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and Soviet dissidents, dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system. He was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature". His non-fiction work ''The Gulag Archipelago'' "amounted to a head-on challenge to the Soviet state" and sold tens of millions of copies. Solzhenitsyn was born into a family that defied the USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928), Soviet anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and remained devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, he initially lost his faith in Christianity, became an atheist, and embraced Marxism–Leninism. While serving as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Virtuous Pagan

Virtuous pagan is a concept in Christian theology that addressed the fate of the unlearned—the issue of nonbelievers who were never evangelized and consequently during their lifetime had no opportunity to recognize Christ, but nevertheless led virtuous lives, so that it seemed objectionable to consider them damned. Prominent examples of virtuous pagans are Heraclitus, Parmenides, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Trajan, and Virgil. A Christian doctrinal formulation of this concept, though not universally accepted, is known as the " Anonymous Christian" in the theology of Karl Rahner, which is analogous to teachings of the gerim toshavim in Judaism and Hanifs in Islam. Biblical and theological foundations In the Bible, Paul the Apostle teaches that the conscience of the pagan will be judged even though they cannot possess the law of God. Paul writes: Certain Church Fathers, while encouraging evangelism of nonbelievers, are known to have taken a more ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Aleksander Ford

Aleksander Ford (born Mosze Lifszyc; 24 November 1908 in Kiev, Russian Empire – 4 April 1980 in Naples, Florida, United States, U.S.) was a Polish film director and head of the Polish People's Army of Poland, People's Army Film Crew in the Soviet Union during World War II. Following the war, he was appointed director of the Film Polski company. In 1948 he was appointed a professor of the National Film School in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa). Roman Polanski and Polish film director Andrzej Wajda were among his students. Amid an anti-Semitic purge in the Polish United Workers' Party, communist party in Poland, Ford was stopped from preparing a film on the life of a Jewish educator. Shortly afterwards he emigrated to Israel in 1968 and from there to the United States, going through West Germany, Germany and Denmark. He took his own life in 1980 in Naples, Florida.Dr. Edyta Gawron, Department of Jewish Studies, Jagiellonian University, Kraków "Contemporary history o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York Times''. Together with entrepreneur Raoul H. Fleischmann, they established the F-R Publishing Company and set up the magazine's first office in Manhattan. Ross remained the editor until his death in 1951, shaping the magazine's editorial tone and standards. ''The New Yorker''s fact-checking operation is widely recognized among journalists as one of its strengths. Although its reviews and events listings often focused on the Culture of New York City, cultural life of New York City, ''The New Yorker'' gained a reputation for publishing serious essays, long-form journalism, well-regarded fiction, and humor for a national and international audience, including work by writers such as Truman Capote, Vladimir Nabokov, and Alice Munro. In the late ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich

''One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich'' (, ) is a short novel by the Russian writer and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, first published in November 1962 in the Soviet literary magazine ''Novy Mir'' (''New World'').One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, or "Odin den iz zhizni Ivana Denisovicha" (novel by Solzhenitsyn) Britannica Online Encyclopedia. The story is set in a Soviet in the early 1950s and features the day of prisoner Ivan Denisovich Sh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lev Kopelev

Lev Zalmanovich (Zinovyevich) Kopelev (, German: Lew Sinowjewitsch Kopelew, 9 April 1912 – 18 June 1997) was a Soviet author and dissident. Early life Kopelev was born in Kyiv, then Russian Empire, to a middle-class Jewish family. In 1926, his family moved to Kharkiv. While a student at Kharkiv State University's philosophy faculty, Kopelev began writing in Russian and Ukrainian languages; some of his articles were published in the '' Komsomolskaya Pravda'' newspaper. An idealist communist and active party member, he was first arrested in March 1929 for "consorting with the Bukharinist and Trotskyist opposition," and spent ten days in prison. Career Later, he worked as an editor of radio news broadcasts at a locomotive factory. In 1932, as a correspondent, Kopelev witnessed the NKVD's forced grain requisitioning and the dekulakization. Later, he described the Holodomor in his memoir ''The Education of a True Believer''. Robert Conquest's '' The Harvest of Sorrow'' later ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange that allocates products in society based on need.: "One widespread distinction was that socialism socialised production only while communism socialised production and consumption." A communist society entails the absence of private property and social classes, and ultimately money and the state. Communists often seek a voluntary state of self-governance but disagree on the means to this end. This reflects a distinction between a libertarian socialist approach of communization, revolutionary spontaneity, and workers' self-management, and an authoritarian socialist, vanguardist, or party-driven approach to establish a socialist state, which is expected to wither away. Communist parties have been described as radi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry. The meaning of the term "humanism" has changed according to successive intellectual movements that have identified with it. During the Italian Renaissance, Italian scholars inspired by Greek classical scholarship gave rise to the Renaissance humanism movement. During the Age of Enlightenment, humanistic values were reinforced by advances in science and technology, giving confidence to humans in their exploration of the world. By the early 20th century, organizations dedicated to humanism flourished in Europe and the United States, and have since expanded worldwide. In the early 21st century, the term generally denotes a focus on human well-being and advocates for human freedom, autonomy, and progress. It views humanity as responsible for the prom ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient philosophy, Stoicism made the greatest claim to being utterly systematic. The Stoics provided a unified account of the world, constructed from ideals of logic, monistic physics, and naturalistic ethics. These three ideals constitute virtue which is necessary for 'living a well reasoned life', seeing as they are all parts of a logos, or philosophical discourse, which includes the mind's rational dialogue with itself. Stoicism was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BC, and flourished throughout the Greco-Roman world until the 3rd century AD, and among its adherents was Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Along with Aristotelian term logic, the system of propositional logic developed by the Stoics was one of th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

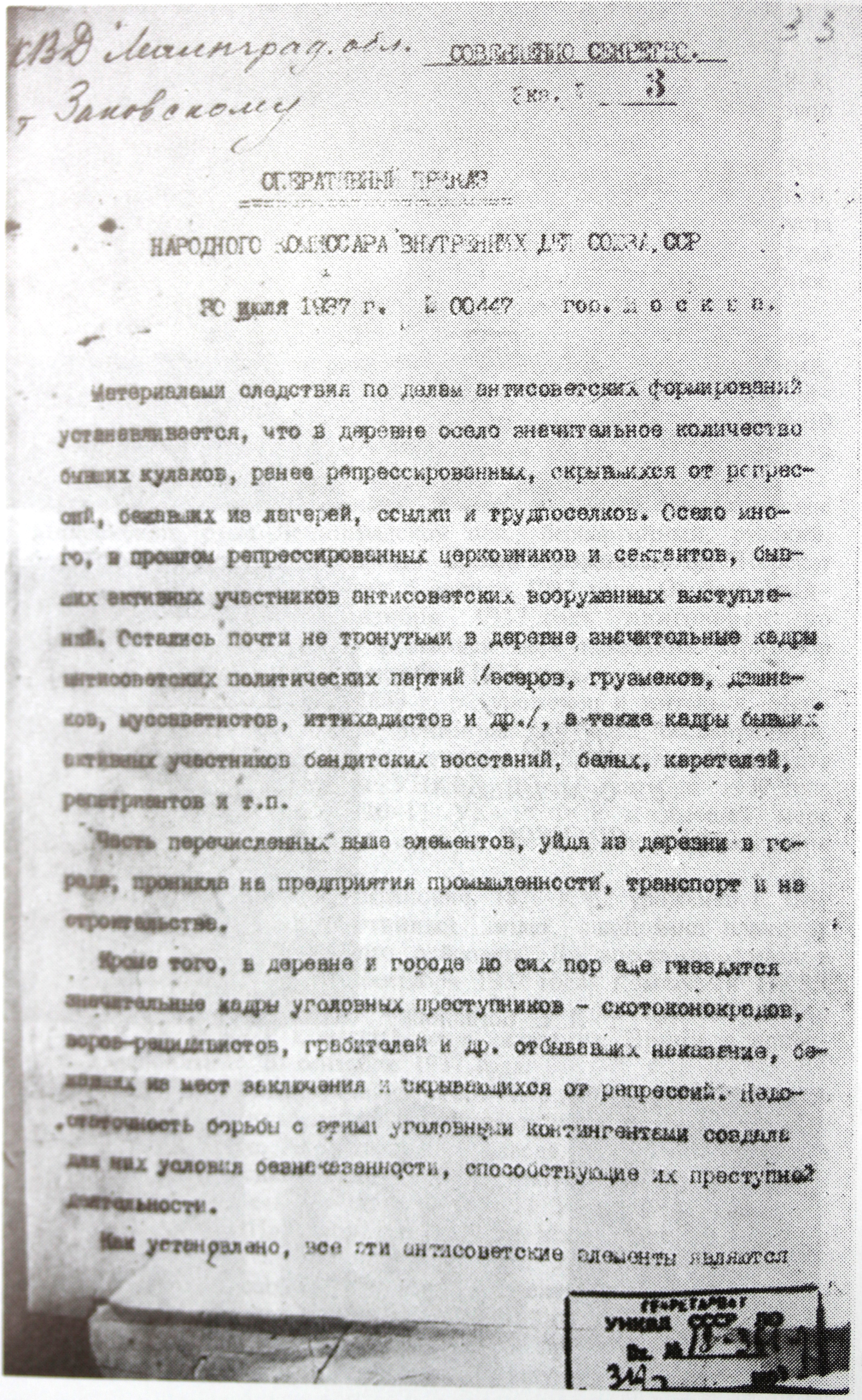

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of Sergei Kirov by Leonid Nikolaev in 1934, Joseph Stalin launched a series of show trials known as the Moscow trials to remove suspected party dissenters from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, especially those aligned with the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik party. The term "great purge" was popularized by the historian Robert Conquest in his 1968 book ''The Great Terror (book), The Great Terror'', whose title was an allusion to the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. The purges were largely conducted by the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs), which functioned as the Ministry of home affairs, interior ministry and secret police of the USSR. Starting in 1936, the NKVD under chief Genrikh Yagoda began the removal of the central pa ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |