|

Mesodinium Pupula

Mesodinium is a genus of ciliates that are widely distributed and are abundant in marine and brackish waters. Currently, six marine species of ''Mesodinium'' have been described and grouped by nutritional mode: plastidic (''M. chamaeleon'', ''M. coatsi'', ''M. major'', and ''M. rubrum'') or heterotrophic (''M. pulex'' and ''M. pupula''). There is some debate as to whether the nutritional mode of plastidic ''Mesodinium ''species is phototrophic (permanent plastid) or mixotrophic. Among the plastidic species, wild ''M. major'' and ''M. rubrum'' populations possess red plastids belonging to genera ''Teleaulax'', ''Plagioselmis'', and ''Geminigera'', while wild ''M. chamaeleon'' and ''M. coatsi'' populations normally contain green plastids.Moestrup, Ø., Garcia-Cuetos, L., Hansen, P. J. & Fenchel, T. (2012) Studies on the genus Mesodinium I: ultrastructure and description of Mesodinium chamaeleon n. sp., a benthic marine species with green or red chloroplasts. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Eukaryota

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacteria and Archaea (both prokaryotes) make up the other two domains. The eukaryotes are usually now regarded as having emerged in the Archaea or as a sister of the Asgard archaea. This implies that there are only two domains of life, Bacteria and Archaea, with eukaryotes incorporated among archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, due to their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass is estimated to be about equal to that of prokaryotes. Eukaryotes emerged approximately 2.3–1.8 billion years ago, during the Proterozoic eon, likely as Flagellated cell, flagellated phagotrophs. Their name comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:εὖ, εὖ (''eu'', "well" or "good") and wikt:� ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

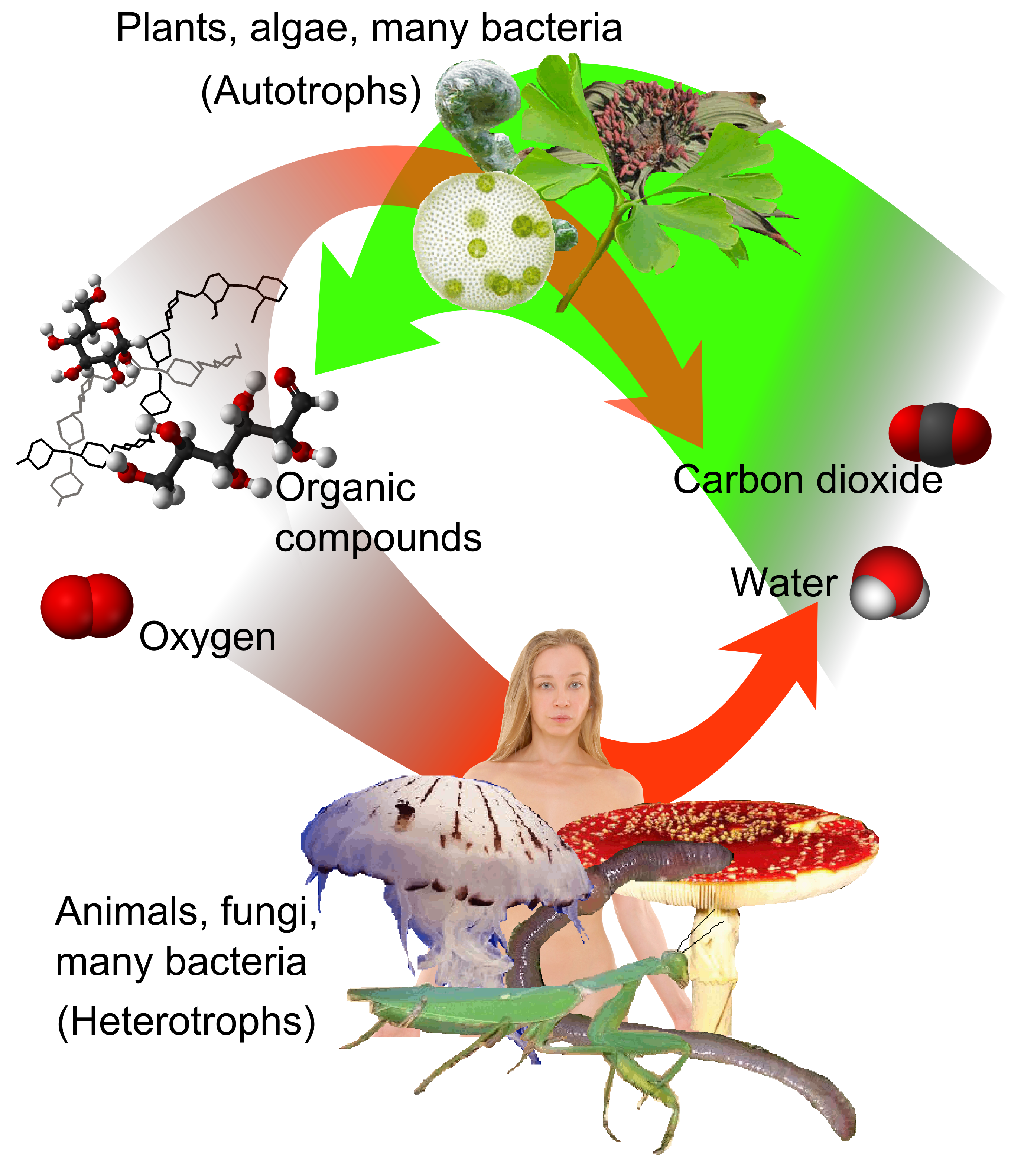

Heterotrophic

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but not producers. Living organisms that are heterotrophic include all animals and fungi, some bacteria and protists, and many parasitic plants. The term heterotroph arose in microbiology in 1946 as part of a classification of microorganisms based on their type of nutrition. The term is now used in many fields, such as ecology in describing the food chain. Heterotrophs may be subdivided according to their energy source. If the heterotroph uses chemical energy, it is a chemoheterotroph (e.g., humans and mushrooms). If it uses light for energy, then it is a photoheterotroph (e.g., green non-sulfur bacteria). Heterotrophs represent one of the two mechanisms of nutrition ( trophic levels), the other being autotrophs (''auto'' = self, ''tr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kleptoplasty

Kleptoplasty or kleptoplastidy is a symbiotic phenomenon whereby plastids, notably chloroplasts from algae, are sequestered by host organisms. The word is derived from ''Kleptes'' (κλέπτης) which is Greek for thief. The alga is eaten normally and partially digested, leaving the plastid intact. The plastids are maintained within the host, temporarily continuing photosynthesis and benefiting the predator. The term was coined in 1990 to describe chloroplast symbiosis. Ciliates ''Mesodinium rubrum'' is a ciliate that steals chloroplasts from the cryptomonad ''Geminigera cryophila''. ''M. rubrum'' participates in additional endosymbiosis by transferring its plastids to its predators, the dinoflagellate planktons belonging to the genus ''Dinophysis''. Karyoklepty is a related process in which the nucleus of the prey cell is kept by the predator as well. This was first described in 2007 in ''M. rubrum''. Dinoflagellates The stability of transient plastids varies considerab ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Karyoklepty

Karyoklepty is a strategy for cellular evolution, whereby a predator cell appropriates the nucleus of a cell from another organism to supplement its own biochemical capabilities. In the related process of kleptoplasty, the predator sequesters plastids (especially chloroplasts) from dietary algae. The chloroplasts can still photosynthesize, but do not last long after the prey's cells are metabolised. If the predator can also sequester cell nuclei from the prey to encode proteins for the plastids, it can sustain them. ''Karyoklepty'' is this sequestration of nuclei; even after sequestration, the nuclei are still capable of transcription. Johnson et al. described and named karyoklepty in 2007 after observing it in the ciliate species ''Mesodinium rubrum''. ''Karyoklepty'' is a Greek compound of the words ''karydi'' ("kernel") and ''kleftis'' ("thief"). See also * Endosymbiont References Further reading * {{cite journal , last1=Nowack , first1=Eva C. M. , last2=Melkonian , fir ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dinophysis

''Dinophysis'' is a genus of dinoflagellates AlgaeBase''Dinophysis'' Ehrenberg, 1839/ref> common in tropical, temperate, coastal and oceanic waters.Hallegraeff, G.M., Lucas, I.A.N. 1988: The marine dinoflagellate genus Dinophysis (Dinophyceae): photosynthetic, neritic and non-photosynthetic, oceanic species. Phycologia, 27: 25–42. 10.2216/i0031-8884-27-1-25.1 It was first described in 1839 by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg.Ehrenberg, C.G., 1839. Über jetzt wirklich noch zahlreich lebende Thier-Arten der Kreideformatien der Erde. Königlich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Bericht über die zur Bekanntmachung geeigneten Verhandlungen, 1839, p. 152-159. Über noch zahlreich jetzt lebende Thierarten der Kreidebildung, nach Vorträgen in der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin in den Jahren 1839 und 1840, L. Voss, LeipzigPDF p. 44ff ''Dinophysis'' are typically medium-sized cells (30-120 µm). The structural plan and plate tabulation are conserve ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cryptomonad

The cryptomonads (or cryptophytes) are a group of algae, most of which have plastids. They are common in freshwater, and also occur in marine and brackish habitats. Each cell is around 10–50 μm in size and flattened in shape, with an anterior groove or pocket. At the edge of the pocket there are typically two slightly unequal flagella. Some may exhibit mixotrophy. Characteristics Cryptomonads are distinguished by the presence of characteristic extrusomes called ejectosomes, which consist of two connected spiral ribbons held under tension. If the cells are irritated either by mechanical, chemical or light stress, they discharge, propelling the cell in a zig-zag course away from the disturbance. Large ejectosomes, visible under the light microscope, are associated with the pocket; smaller ones occur underneath the periplast, the cryptophyte-specific cell surrounding. Except for the class '' Goniomonadea'', which lacks plastids entirely, and ''Cryptomonas paramecium'' ( ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

CC-BY Icon

A Creative Commons (CC) license is one of several public copyright licenses that enable the free distribution of an otherwise copyrighted "work".A "work" is any creative material made by a person. A painting, a graphic, a book, a song/lyrics to a song, or a photograph of almost anything are all examples of "works". A CC license is used when an author wants to give other people the right to share, use, and build upon a work that the author has created. CC provides an author flexibility (for example, they might choose to allow only non-commercial uses of a given work) and protects the people who use or redistribute an author's work from concerns of copyright infringement as long as they abide by the conditions that are specified in the license by which the author distributes the work. There are several types of Creative Commons licenses. Each license differs by several combinations that condition the terms of distribution. They were initially released on December 16, 2002, by ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Red Tide

A harmful algal bloom (HAB) (or excessive algae growth) is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural phycotoxin, algae-produced toxins, mechanical damage to other organisms, or by other means. HABs are sometimes defined as only those algal blooms that produce toxins, and sometimes as any algal bloom that can result in severely lower oxygen saturation, oxygen levels in natural waters, killing organisms in marine habitats, marine or fresh waters. Blooms can last from a few days to many months. After the bloom dies, the microorganism, microbes that decompose the dead algae use up more of the oxygen, generating a "dead zone (ecology), dead zone" which can cause fish kill, fish die-offs. When these zones cover a large area for an extended period of time, neither fish nor plants are able to survive. Harmful algal blooms in marine environments are often called "red tides". It is sometimes unclear what causes specific HABs as their occurrence ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Geminigera

''Geminigera'' /ˌdʒɛmɪnɪˈdʒɛɹə/ is a genus of cryptophyte from the family Geminigeraceae Geminigeraceae is a family of cryptophytes containing the five genera ''Geminigera'', ''Guillardia'', ''Hanusia'', ''Proteomonas'' and ''Teleaulax''. They are characterised by chloroplasts containing Cr-phycoerythrin 545, and an inner periplast .... Named for its unique pyrenoids, ''Geminigera'' is a genus with a single mixotrophic species. It was discovered in 1968 and is known for living in very cold temperatures such as under the Antarctic ice. While originally considered to be part of the genus ''Cryptomonas'', the genus ''Geminigera'' was officially described in 1991 by D. R. A. Hill. Etymology The genus ''Geminigera'' was named for its unique paired pyrenoids. The name in Latin means "bearer of twins" and was suggested in the original article that declared the genus separate from ''Cryptomonas''. History While the genus ''Geminigera'' was originally described in 19 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Plagioselmis

''Plagioselmis'' is a genus of cryptophytes, including the species ''Plagioselmis punctata''. ''Plagioselmis'' was first described by Butcher in 1967 as a saltwater life form. In 1994, Novarino placed the freshwater Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ... ''Rhodomonas minuta'' into the genus, giving it the new binomial name of ''Plagioselmis nanoplantica''. ''Nanoplantica'' is the only freshwater species in this genus. ''Rhodomonas'' was first described by Klaveness, who agreed with the reclassification. The cells are comma-shaped and appear red or similar colors. Some strains within the genus appear to have a furrow, while other do not. Researchers have suggested that those without furrows should be placed into a new genus. References Cryptomonad genera ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Teleaulax

Geminigeraceae is a family of cryptophytes containing the five genera ''Geminigera'', ''Guillardia'', ''Hanusia'', ''Proteomonas'' and ''Teleaulax''. They are characterised by chloroplast A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...s containing Cr-phycoerythrin 545, and an inner periplast component (IPC) comprising "a sheet or a sheet and multiple plates if diplomorphic". The nucleomorphs are never in the pyrenoid, and there is never a scalariform furrow. The cells do, however, have a long, keeled rhizostyle with lamellae (wings). References Cryptomonads Eukaryote families {{Cryptomonad-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mixotrophic

A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comprise more than half of all microscopic plankton. There are two types of eukaryotic mixotrophs: those with their own chloroplasts, and those with endosymbionts—and those that acquire them through kleptoplasty or by enslaving the entire phototrophic cell. Possible combinations are photo- and chemotrophy, litho- and organotrophy (osmotrophy, phagotrophy and myzocytosis), auto- and heterotrophy or other combinations of these. Mixotrophs can be either eukaryotic or prokaryotic. They can take advantage of different environmental conditions. If a trophic mode is obligate, then it is always necessary for sustaining growth and maintenance; if facultative, it can be used as a supplemental source. Some organisms have incomplete Calvin cycles, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |