|

Holweck Pump

A molecular drag pump is a type of vacuum pump that utilizes the drag of air molecules against a rotating surface. The most common sub-type is the ''Holweck pump'', which contains a rotating cylinder with spiral grooves which direct the gas from the high-vacuum side of the pump to the low-vacuum side of the pump. The older ''Gaede pump'' design is similar, but is much less common due to disadvantages in pumping speed. In general, molecular drag pumps are more efficient for heavy gases, so the lighter gases (hydrogen, deuterium, helium) will make up the majority of the residual gases left after running a molecular drag pump. The turbomolecular pump invented in the 1950s, is a more advanced version based on similar operation, and a Holweck pump is often used as the backing pump for it. The Holweck pump can produce a vacuum as low as . History Gaede The earliest molecular drag pump was created by Wolfgang Gaede, who had the idea of the pump in 1905, and spent several years correspon ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vacuum Pump

A vacuum pump is a type of pump device that draws gas particles from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto von Guericke, and was preceded by the suction pump, which dates to antiquity. History Early pumps The predecessor to the vacuum pump was the suction pump. Dual-action suction pumps were found in the city of Pompeii. Arabic engineer Al-Jazari later described dual-action suction pumps as part of water-raising machines in the 13th century. He also said that a suction pump was used in siphons to discharge Greek fire. The suction pump later appeared in medieval Europe from the 15th century. Donald Routledge Hill (1996), ''A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times'', Routledge, pp. 143 & 150-2 Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", ''Scientific American'', May 1991, pp. 64-69 (cf. Donald Routledge HillMechanical Engineering By the 17th century, water ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kinetic Theory Of Gases

The kinetic theory of gases is a simple classical model of the thermodynamic behavior of gases. Its introduction allowed many principal concepts of thermodynamics to be established. It treats a gas as composed of numerous particles, too small to be seen with a microscope, in constant, random motion. These particles are now known to be the atoms or molecules of the gas. The kinetic theory of gases uses their collisions with each other and with the walls of their container to explain the relationship between the macroscopic properties of gases, such as volume, pressure, and temperature, as well as transport properties such as viscosity, thermal conductivity and mass diffusivity. The basic version of the model describes an ideal gas. It treats the collisions as perfectly elastic and as the only interaction between the particles, which are additionally assumed to be much smaller than their average distance apart. Due to the time reversibility of microscopic dynamics ( microsco ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Micrometre

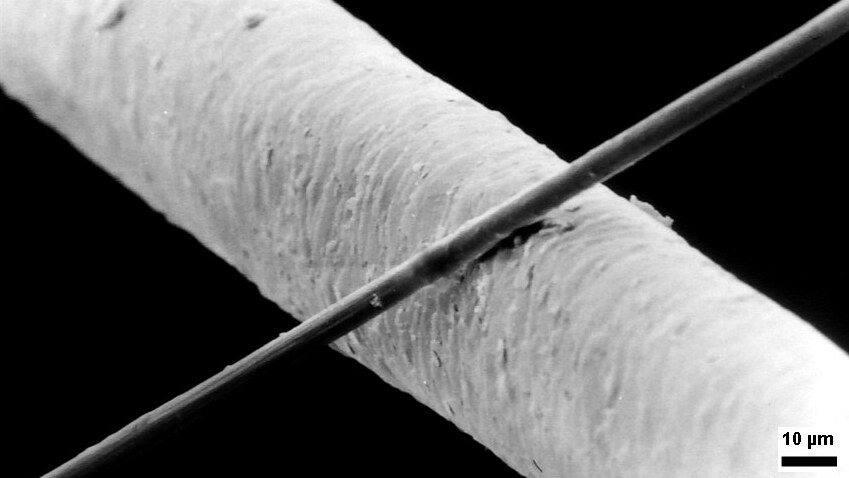

The micrometre (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Units (SI) equalling (SI standard prefix "micro-" = ); that is, one millionth of a metre (or one thousandth of a millimetre, , or about ). The nearest smaller common SI Unit, SI unit is the nanometre, equivalent to one thousandth of a micrometre, one millionth of a millimetre or one billionth of a metre (). The micrometre is a common unit of measurement for wavelengths of infrared radiation as well as sizes of biological cell (biology), cells and bacteria, and for grading wool by the diameter of the fibres. The width of a single human hair ranges from approximately 20 to . Examples Between 1 μm and 10 μm: * 1–10 μm – length of a typical bacterium * 3–8 μm – width of str ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Diffusion Pump

Diffusion pumps use a high speed jet of vapor to direct gas molecules in the pump throat down into the bottom of the pump and out the exhaust. They were the first type of high vacuum pumps operating in the regime of free molecular flow, where the movement of the gas molecules can be better understood as diffusion than by conventional fluid dynamics. Invented in 1915 by Wolfgang Gaede, he named it a ''diffusion pump'' since his design was based on the finding that gas cannot diffuse against the vapor stream, but will be carried with it to the exhaust. However, the principle of operation might be more precisely described as gas-jet pump, since diffusion also plays a role in other types of high vacuum pumps. In modern textbooks, the diffusion pump is categorized as a vacuum pump#Momentum transfer, momentum transfer pump. The diffusion pump is widely used in both industrial and research applications. Most modern diffusion pumps use silicone oil or polyphenyl ethers as the working flui ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: January 26, 1932, granted: February 20, 1934 A cyclotron accelerates charged particles outwards from the center of a flat cylindrical vacuum chamber along a spiral path. The particles are held to a spiral trajectory by a static magnetic field and accelerated by a rapidly varying electric field. Lawrence was awarded the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physics for this invention. The cyclotron was the first "cyclical" accelerator. The primary accelerators before the development of the cyclotron were electrostatic accelerators, such as the Cockcroft–Walton generator and the Van de Graaff generator. In these accelerators, particles would cross an accelerating electric field only once. Thus, the energy gained by the particles was limited by the maximum ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation. Initially founded in the 15th century, the university rose to significance during the rise of Swedish Empire, Sweden as a great power at the end of the 16th century and was then given relative financial stability with a large donation from Monarchy of Sweden, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus in the early 17th century. Uppsala also has an important historical place in Swedish national culture, and national identity, identity for the Swedish establishment: in historiography, religion, literature, politics, and music. Many aspects of Swedish academic culture in general, such as the white student cap, originated in Uppsala. It shares some peculiarities, such as the student nation system, with Lund University and the University of Helsink ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Manne Siegbahn

Karl Manne Georg Siegbahn (; 3 December 1886 – 26 September 1978) was a Swedish physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1924 "for his discoveries and research in the field of X-ray spectroscopy". Biography Siegbahn was born in Örebro, Sweden, the son of Georg Siegbahn and his wife, Emma Zetterberg. He graduated in Stockholm 1906 and began his studies at Lund University in the same year. During his education he was secretarial assistant to Johannes Rydberg. In 1908 he studied at the University of Göttingen. He obtained his doctorate (PhD) at the Lund University in 1911, his thesis was titled ''Magnetische Feldmessungen'' (magnetic field measurements). He became acting professor for Rydberg when his (Rydberg's) health was failing, and succeeded him as full professor in 1920. However, in 1922 he left Lund for a professorship at Uppsala University. In 1937, Siegbahn was appointed Director of the Physics Department of the Nobel Institute of the Royal Swedish Academy ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Soft X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 nanometers to 10 picometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range of 30 petahertz to 30 exahertz ( to ) and photon energies in the range of 100 eV to 100 keV, respectively. X-rays were discovered in 1895 by the German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who named it ''X-radiation'' to signify an unknown type of radiation.Novelline, Robert (1997). ''Squire's Fundamentals of Radiology''. Harvard University Press. 5th edition. . X-rays can penetrate many solid substances such as construction materials and living tissue, so X-ray radiography is widely used in medical diagnostics (e.g., checking for broken bones) and materials science (e.g., identification of some chemical elements and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fernand Holweck

Fernand Holweck (21 July 1890 – 24 December 1941) was a French physicist who made important contributions in the fields of vacuum technology, electromagnetic radiation and gravitation. He is also remembered for his personal sacrifice in the cause of the French Resistance and his aid to Allied airmen in World War II. Biography Holweck was born on 21 July 1890 to a family from the Alsace Region who had opted to remain French at the end of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870. He studied at the École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris (ESPCI), where he graduated top of his class in engineering physics and became personal assistant to Marie Curie. During his military service he worked under the wireless telegraphy pioneer Gustave-Auguste Ferrié at the Eiffel Tower radio station, and by 1914 he had produced his first patent, relating to thermionic tubes. During World War I, 1914–1918, he served first at the front, working on methods to detect ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vacuum Gauge ...

{{Cat main, Vacuum system Vacuum Systems A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and is exp ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Thermal Velocity

Thermal velocity or thermal speed is a typical velocity of the thermal motion of particles that make up a gas, liquid, etc. Thus, indirectly, thermal velocity is a measure of temperature. Technically speaking, it is a measure of the width of the peak in the Maxwell–Boltzmann particle velocity distribution. Note that in the strictest sense ''thermal velocity'' is not a velocity, since ''velocity'' usually describes a vector rather than simply a scalar speed. Definitions Since the thermal velocity is only a "typical" velocity, a number of different definitions can be and are used. Taking k_\text to be the Boltzmann constant, T the absolute temperature, and m the mass of a particle, we can write the different thermal velocities: In one dimension If v_\text is defined as the root mean square of the velocity in any one dimension (i.e. any single direction), then v_\text = \sqrt. If v_\text is defined as the mean of the magnitude of the velocity in any one dimension (i.e. any si ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Free Molecular Flow

Free molecular flow describes the fluid dynamics of gas where the mean free path of the molecules is larger than the size of the chamber or of the object under test. For tubes/objects of the size of several cm, this means pressures well below 10−3 mbar. This is also called the regime of high vacuum, or even ultra-high vacuum. This is opposed to viscous flow encountered at higher pressures. The presence of free molecular flow can be calculated, at least in estimation, with the Knudsen number (Kn). If Kn > 10, the system is in free molecular flow, also known as Knudsen flow. Knudsen flow has been defined as the transitional range between viscous flow and molecular flow, which is significant in the medium vacuum range where λ ≈ d. Gas flow can be grouped in four regimes: For Kn≤0.001, flow is continuous, and the Navier–Stokes equations are applicable, from 0.001 [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |