|

Bacteriophage Lambda

Lambda phage (coliphage λ, scientific name ''Lambdavirus lambda'') is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species ''Escherichia coli'' (''E. coli''). It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of this virus has a temperate life cycle that allows it to either reside within the genome of its host through lysogeny or enter into a lytic phase, during which it kills and lyses the cell to produce offspring. Lambda strains, mutated at specific sites, are unable to lysogenize cells; instead, they grow and enter the lytic cycle after superinfecting an already lysogenized cell. The phage particle consists of a head (also known as a capsid), a tail, and tail fibers (see image of virus below). The head contains the phage's double-strand linear DNA genome. During infections, the phage particle recognizes and binds to its host, ''E. coli'', causing DNA in the head of the phage to be ejected through the tail into the cytoplasm of the bacterial ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacteriophage Lambda Structure

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes (e.g. Bacteriophage MS2, MS2) and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm. Bacteriophages are among the most common and diverse entities in the biosphere. Bacteriophages are ubiquitous viruses, found wherever bacteria exist. It is estimated there are more than 1031 bacteriophages on the planet, more than every other organism on Earth, including bacteria, combined. Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in the water column of the world's oceans, and the second largest component of biomass after prokaryotes, where up to 9x108 virus, virions per millilitre have b ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Multiplicity Of Infection

In microbiology, the multiplicity of infection or MOI is the ratio of agents (e.g. phage or more generally virus, bacteria) to infection targets (e.g. cell). For example, when referring to a group of cells inoculated with virus particles, the MOI is the ratio of the number of virus particles to the number of target cells present in a defined space. Interpretation The actual number of viruses or bacteria that will enter any given cell is a stochastic process: some cells may absorb more than one infectious agent, while others may not absorb any. Before determining the multiplicity of infection, it's absolutely necessary to have a well-isolated agent, as crude agents may not produce reliable and reproducible results. The probability that a cell will absorb n virus particles or bacteria when inoculated with an MOI of m can be calculated for a given population using a Poisson distribution. This application of Poisson's distribution was applied and described by Ellis and Delbrück. : ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

CII Protein

cII or transcriptional activator II is a DNA-binding protein and important transcription factor in the life cycle of lambda phage. It is encoded in the lambda phage genome by the 291 base pair cII gene. cII plays a key role in determining whether the bacteriophage will incorporate its genome into its host and lie dormant (lysogeny), or replicate and kill the host (lytic cycle, lysis). Introduction cII is the central “switchman” in the lambda phage bistable genetic switch, allowing environmental and cellular conditions to factor into the decision to lysogenize or to lyse its host. cII acts as a transcriptional activator of three promoter (genetics), promoters on the phage genome: pI, pRE, and pAQ. cII is an unstable protein with a half-life as short as 1.5 mins at 37˚C, enabling rapid fluctuations in its concentration. First isolated in 1982, cII's function in lambda's regulatory network has been extensively studied. Structure and properties cII binds DNA as a tetramer, comp ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacteriostatic

A bacteriostatic agent or bacteriostat, abbreviated Bstatic, is a biological or chemical agent that stops bacteria from reproducing, while not necessarily killing them otherwise. Depending on their application, bacteriostatic antibiotics, disinfectants, antiseptics and preservatives can be distinguished. When bacteriostatic antimicrobials are used, the duration of therapy must be sufficient to allow host defense mechanisms to eradicate the bacteria. Upon removal of the bacteriostat, the bacteria usually start to grow rapidly. This is in contrast to bactericides, which kill bacteria. Bacteriostats are often used in plastics to prevent growth of bacteria on surfaces. Bacteriostats commonly used in laboratory work include sodium azide (which is acutely toxic) and thiomersal. __TOC__ Bacteriostatic antibiotics Bacteriostatic antibiotics limit the growth of bacteria by interfering with bacterial protein production, DNA replication, or other aspects of bacterial cellular metabolism. Th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

RNA Polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template. Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the double-stranded DNA so that one strand of the exposed nucleotides can be used as a template for the synthesis of RNA, a process called transcription. A transcription factor and its associated transcription mediator complex must be attached to a DNA binding site called a promoter region before RNAP can initiate the DNA unwinding at that position. RNAP not only initiates RNA transcription, it also guides the nucleotides into position, facilitates attachment and elongation, has intrinsic proofreading and replacement capabilities, and termination recognition capability. In eukaryotes, RNAP can build chains as long as 2.4 million nucleotides. RNAP produces RNA that, functionally, is either for protei ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Antiterminator

{{short description, Genetic transcription mechanism in prokaryotes In molecular biology, antitermination is the prokaryotic cell's aid to fix premature termination during the transcription of RNA. It occurs when the RNA polymerase ignores the termination signal and continues elongating its transcript until a second signal is reached. Antitermination provides a mechanism whereby one or more genes at the end of an operon can be switched either on or off, depending on the polymerase either recognizing or not recognizing the termination signal. Antitermination is used by some phages to regulate progression from one stage of gene expression to the next. The lambda gene N, codes for an antitermination protein (pN) that is necessary to allow RNA polymerase to read through the terminators located at the ends of the immediate early genes. Another antitermination protein, pQ, is required later in phage infection. pN and pQ act on RNA polymerase as it passes specific sites. These sites ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

N Protien

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''. History One of the most common hieroglyphs, snake, was used in Egyptian writing to stand for a sound like the English , because the Egyptian word for "snake" was ''djet''. It is speculated by some, such as archeologist Douglas Petrovich, that Semitic speakers working in Egypt adapted hieroglyphs to create the first alphabet. Some hold that they used the same snake symbol to represent N, with a great proponent of this theory being Alan Gardiner, because their word for "snake" may have begun with n (an example of a possible word being ''nahash''). However, this theory has become disputed. The name for the letter in the Phoenician, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic alphabets is ''nun'', which means "fish" in some of these languages. This possibly co ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Promoter (biology)

In genetics, a promoter is a sequence of DNA to which proteins bind to initiate transcription (genetics), transcription of a single RNA transcript from the DNA downstream of the promoter. The RNA transcript may encode a protein (mRNA), or can have a function in and of itself, such as tRNA or rRNA. Promoters are located near the transcription start sites of genes, Upstream and downstream (DNA), upstream on the DNA (towards the Directionality (molecular biology)#5′-end, 5' region of the sense strand). Promoters can be about 100–1000 base pairs long, the sequence of which is highly dependent on the gene and product of transcription, type or class of RNA polymerase recruited to the site, and species of organism. Overview For transcription to take place, the enzyme that synthesizes RNA, known as RNA polymerase, must attach to the DNA near a gene. Promoters contain specific DNA sequences such as response elements that provide a secure initial binding site for RNA polymerase and for ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Supercoil

DNA supercoiling refers to the amount of twist in a particular DNA strand, which determines the amount of strain on it. A given strand may be "positively supercoiled" or "negatively supercoiled" (more or less tightly wound). The amount of a strand's supercoiling affects a number of biological processes, such as compacting DNA and regulating access to the genetic code (which strongly affects Nucleic acid metabolism, DNA metabolism and possibly gene expression). Certain enzymes, such as topoisomerases, change the amount of DNA supercoiling to facilitate functions such as DNA replication and Transcription (genetics), transcription. The amount of supercoiling in a given strand is described by a mathematical formula that compares it to a reference state known as "relaxed B-form" DNA. Overview In a "relaxed" Nucleic acid double helix, double-helical segment of B-DNA, the two strands twist around the helical axis once every 10.4–10.5 base pairs of DNA sequence, sequence. Adding or ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA Gyrase

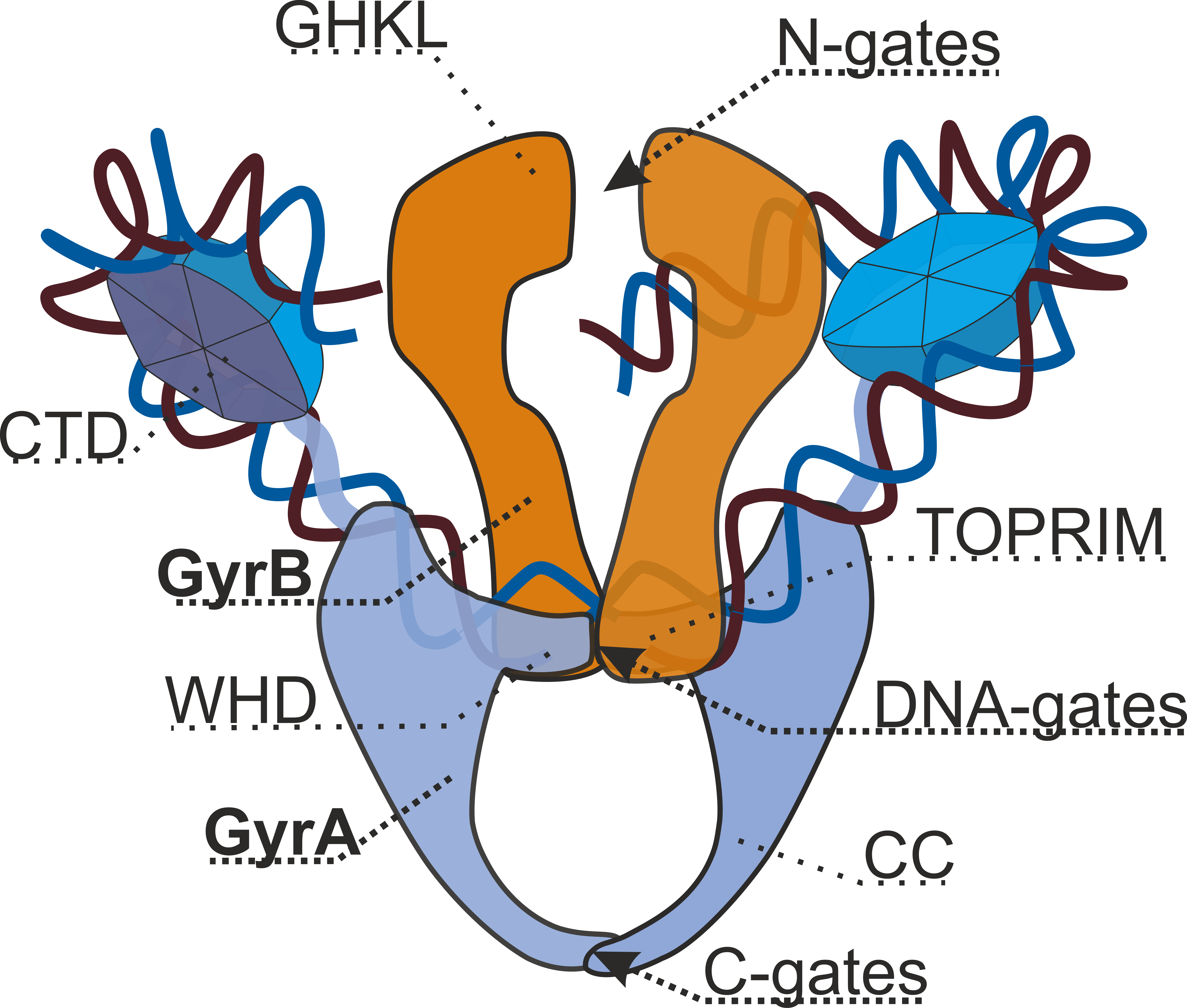

DNA gyrase, or simply gyrase, is an enzyme within the class of topoisomerase and is a subclass of Type II topoisomerases that reduces topological strain in an ATP dependent manner while double-stranded DNA is being unwound by elongating RNA-polymerase or by helicase in front of the progressing replication fork. It is the only known enzyme to actively contribute negative supercoiling to DNA, while it also is capable of relaxing positive supercoils. It does so by looping the template to form a crossing, then cutting one of the double helices and passing the other through it before releasing the break, changing the linking number by two in each enzymatic step. This process occurs in bacteria, whose single circular DNA is cut by DNA gyrase and the two ends are then twisted around each other to form supercoils. Gyrase is also found in eukaryotic plastids: it has been found in the apicoplast of the malarial parasite ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and in chloroplasts of several plants. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |