|

Anti-CRISPR

Anti-CRISPR (Anti-Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats or Acr) is a group of proteins found in Bacteriophage, phages, that inhibit the normal activity of CRISPR-Cas, the immune system of certain bacteria. CRISPR consists of Genome, genomic sequences that can be found in Prokaryote, prokaryotic organisms, that come from bacteriophages that infected the bacteria beforehand, and are used to defend the cell from further viral attacks. Anti-CRISPR results from an evolutionary process occurred in phages in order to avoid having their genomes destroyed by the Prokaryote, prokaryotic cells that they will infect. Before the discovery of this type of family proteins, the acquisition of mutations was the only way known that phages could use to avoid CRISPR, CRISPR-Cas mediated shattering, by reducing the binding affinity of the phage and CRISPR. Nonetheless, bacteria have mechanisms to retarget the mutant bacteriophage, a process that it is called "priming adaptation". S ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

CRISPR

CRISPR () (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of bacteriophages that had previously infected the prokaryote. They are used to detect and destroy DNA from similar bacteriophages during subsequent infections. Hence these sequences play a key role in the antiviral (i.e. anti-phage) defense system of prokaryotes and provide a form of acquired immunity. CRISPR is found in approximately 50% of sequenced bacterial genomes and nearly 90% of sequenced archaea. Cas9 (or "CRISPR-associated protein 9") is an enzyme that uses CRISPR sequences as a guide to recognize and cleave specific strands of DNA that are complementary to the CRISPR sequence. Cas9 enzymes together with CRISPR sequences form the basis of a technology known as CRISPR-Cas9 that can be used to edit genes within organisms. This ed ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes (e.g. MS2) and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm. Bacteriophages are among the most common and diverse entities in the biosphere. Bacteriophages are ubiquitous viruses, found wherever bacteria exist. It is estimated there are more than 1031 bacteriophages on the planet, more than every other organism on Earth, including bacteria, combined. Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in the water column of the world's oceans, and the second largest component of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Stacking (chemistry)

In chemistry, pi stacking (also called π–π stacking) refers to the presumptive attractive, noncovalent pi interactions (orbital overlap) between the pi bonds of aromatic rings. However this is a misleading description of the phenomena since direct stacking of aromatic rings (the "sandwich interaction") is electrostatically repulsive. What is more commonly observed (see figure to the right) is either a staggered stacking (parallel displaced) or pi-teeing (perpendicular T-shaped) interaction both of which are electrostatic attractive For example, the most commonly observed interactions between aromatic rings of amino acid residues in proteins is a staggered stacked followed by a perpendicular orientation. Sandwiched orientations are relatively rare. Pi stacking is repulsive as it places carbon atoms with partial negative charges from one ring on top of other partial negatively charged carbon atoms from the second ring and hydrogen atoms with partial positive charges on top ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

310 Helix

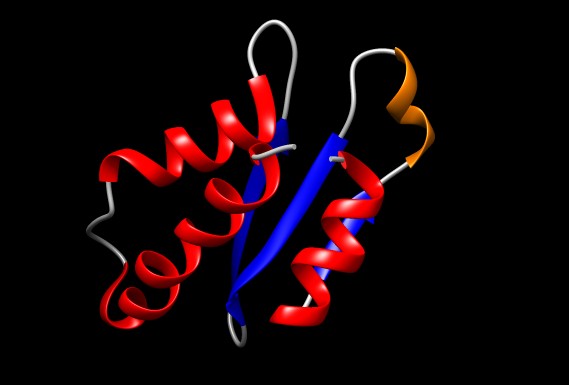

A 310 helix is a type of secondary structure found in proteins and polypeptides. Of the numerous protein secondary structures present, the 310-helix is the fourth most common type observed; following α-helices, β-sheets and reverse turns. 310-helices constitute nearly 10–15% of all helices in protein secondary structures, and are typically observed as extensions of α-helices found at either their N- or C- termini. Because of the α-helices tendency to consistently fold and unfold, it has been proposed that the 310-helix serves as an intermediary conformation of sorts, and provides insight into the initiation of α-helix folding. Discovery Max Perutz, the head of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology at the University of Cambridge, wrote the first paper documenting the elusive 310-helix. Together with Lawrence Bragg and John Kendrew, Perutz published an exploration of polypeptide chain configurations in 1950, based on cues from noncrystalline dif ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alpha Helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues earlier along the protein sequence. The alpha helix is also called a classic Pauling–Corey–Branson α-helix. The name 3.613-helix is also used for this type of helix, denoting the average number of residues per helical turn, with 13 atoms being involved in the ring formed by the hydrogen bond. Among types of local structure in proteins, the α-helix is the most extreme and the most predictable from sequence, as well as the most prevalent. Discovery In the early 1930s, William Astbury showed that there were drastic changes in the X-ray fiber diffraction of moist wool or hair fibers upon significant stretching. The data suggested that the unstretched fibers had a coiled molecular structure with a characteristic repeat of ≈. Astbu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Beta Sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a generally twisted, pleated sheet. A β-strand is a stretch of polypeptide chain typically 3 to 10 amino acids long with backbone in an extended conformation. The supramolecular association of β-sheets has been implicated in the formation of the fibrils and protein aggregates observed in amyloidosis, notably Alzheimer's disease. History The first β-sheet structure was proposed by William Astbury in the 1930s. He proposed the idea of hydrogen bonding between the peptide bonds of parallel or antiparallel extended β-strands. However, Astbury did not have the necessary data on the bond geometry of the amino acids in order to build accurate models, especially since he did not then know that the peptide bond was planar. A refined version was ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a frequency characteristic of the magnetic field at the nucleus. This process occurs near resonance, when the oscillation frequency matches the intrinsic frequency of the nuclei, which depends on the strength of the static magnetic field, the chemical environment, and the magnetic properties of the isotope involved; in practical applications with static magnetic fields up to ca. 20 tesla, the frequency is similar to VHF and UHF television broadcasts (60–1000 MHz). NMR results from specific magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is widely used to determine the structure of organic molecules in solution and study molecular physics and crystals as well as non-crystalline materials. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mobile Genetic Elements

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) sometimes called selfish genetic elements are a type of genetic material that can move around within a genome, or that can be transferred from one species or replicon to another. MGEs are found in all organisms. In humans, approximately 50% of the genome is thought to be MGEs. MGEs play a distinct role in evolution. Gene duplication events can also happen through the mechanism of MGEs. MGEs can also cause mutations in protein coding regions, which alters the protein functions. These mechanisms can also rearrange genes in the host genome generating variation. These mechanism can increase fitness by gaining new or additional functions. An example of MGEs in evolutionary context are that virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes of MGEs can be transported to share genetic code with neighboring bacteria. However, MGEs can also decrease fitness by introducing disease-causing alleles or mutations. The set of MGEs in an organism is called a mobilome ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, Gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae and containing 191 described species. The members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able to colonize a wide range of niches. Their ease of culture ''in vitro'' and availability of an increasing number of ''Pseudomonas'' strain genome sequences has made the genus an excellent focus for scientific research; the best studied species include '' P. aeruginosa'' in its role as an opportunistic human pathogen, the plant pathogen '' P. syringae'', the soil bacterium '' P. putida'', and the plant growth-promoting '' P. fluorescens, P. lini, P. migulae'', and ''P. graminis''. Because of their widespread occurrence in water and plant seeds such as dicots, the pseudomonads were observed early in the history of microbiology. The generic name ''Pseudomonas'' created for these organisms was defined in rather vague terms by Walter Migula ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pathogenicity Island

Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), as termed in 1990, are a distinct class of genomic islands acquired by microorganisms through horizontal gene transfer. Pathogenicity islands are found in both animal and plant pathogens. Additionally, PAIs are found in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. They are transferred through horizontal gene transfer events such as transfer by a plasmid, phage, or conjugative transposon. Therefore, PAIs contribute to microorganisms' ability to evolve. One species of bacteria may have more than one PAI. For example, ''Salmonella'' has at least five. An analogous genomic structure in rhizobia is termed a ''symbiosis island''. Properties Pathogenicity islands (PAIs) are gene clusters incorporated in the genome, chromosomally or extrachromosomally, of pathogenic organisms, but are usually absent from those nonpathogenic organisms of the same or closely related species. They may be located on a bacterial chromosome or may be transferred within a plasmi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Putative Conjugative Elements

{{Short pages monitor ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |