Thomas H. Ince on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Harper Ince (November 16, 1880 – November 19, 1924) was an American silent film - era filmmaker and media proprietor.

Ince was known as the "Father of the Western" and was responsible for making over 800 films. He revolutionized the motion picture industry by creating the first major Hollywood studio facility and invented

Thomas Harper Ince was born on November 16, 1880 in

Thomas Harper Ince was born on November 16, 1880 in

movie production

Filmmaking (film production) is the process by which a motion picture is produced. Filmmaking involves a number of complex and discrete stages, starting with an initial story, idea, or commission. It then continues through screenwriting, castin ...

by introducing the "assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

" system of filmmaking

Filmmaking (film production) is the process by which a motion picture is produced. Filmmaking involves a number of complex and discrete stages, starting with an initial story, idea, or commission. It then continues through screenwriting, cast ...

. He was the first mogul to build his own film studio dubbed "Inceville" in Palisades Highlands. Ince was also instrumental in developing the role of the producer in motion pictures. Three of his films, '' The Italian'' (1915), for which he wrote the screenplay

''ScreenPlay'' is a television drama anthology series broadcast on BBC2 between 9 July 1986 and 27 October 1993.

Background

After single-play anthology series went off the air, the BBC introduced several showcases for made-for-television, f ...

, ''Hell's Hinges

''Hell's Hinges'' is a 1916 American silent Western film starring William S. Hart and Clara Williams. Directed by Charles Swickard, William S. Hart and Clifford Smith, and produced by Thomas H. Ince, the screenplay was written by C. Gardner ...

'' (1916) and ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

'' (1916), which he directed, were selected for preservation

Preservation may refer to:

Heritage and conservation

* Preservation (library and archival science), activities aimed at prolonging the life of a record while making as few changes as possible

* ''Preservation'' (magazine), published by the Nat ...

by the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

. He later entered into a partnership with D. W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the n ...

and Mack Sennett to form the Triangle Motion Picture Company, whose studios are the present-day site of Sony Pictures

Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Sony Pictures or SPE, and formerly known as Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc.) is an American diversified multinational mass media and entertainment studio conglomerate that produces, acq ...

. He then built a new studio about a mile from Triangle, which is now the site of Culver Studios. Ince's untimely death at the height of his career, after he became severely ill aboard the private yacht of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, has caused much speculation, although the official cause of his death was heart failure. Taves' extensive biography contains a strong rebuttal to the much rumored murder of Thomas Ince; see pp. 1-13.

Life and career

Thomas Harper Ince was born on November 16, 1880 in

Thomas Harper Ince was born on November 16, 1880 in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, the middle of three sons and a daughter raised by English immigrants, John E. and Emma Ince. His father was born in Wigan

Wigan ( ) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, on the River Douglas. The town is midway between the two cities of Manchester, to the south-east, and Liverpool, to the south-west. Bolton lies to the north-east and Warrington ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

in 1841, and was the youngest of nine boys who enlisted in the British Navy as a " powder monkey". He later disembarked at San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, and found work as a reporter and coal miner. Around 1887, when Ince was about seven, the family moved to Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

to pursue theater work. Ince's father worked as both an actor and musical agent and his mother, Ince himself, sister Bertha and brothers, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and Ralph all worked as actors. Ince made his Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

debut at 15 in a small role of a revival 1893 play, ''Shore Acres'' by James A. Herne. He appeared with several stock companies as a child and was later an office boy for theatrical manager Daniel Frohman. He later formed an unsuccessful vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

company known as "Thomas H. Ince and His Comedians" in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey

Atlantic Highlands is a borough in Monmouth County, New Jersey, in the Bayshore Region. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough's population was 4,385,Elinor Kershaw ("Nell") and they were married on October 19 of that year. They had three children.

Ince's directing career began in 1910 through a chance encounter in

The "Miller 101 Bison Ranch Studio", which the Millers dubbed "Inceville" (and was later re-christened "Triangle Ranch") was the first of its kind in that it featured silent stages, production offices, printing labs, a commissary large enough to serve lunch to hundreds of workers, dressing rooms, props houses, elaborate sets, and other necessities – all in one location. While the site was under construction, Ince also leased the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show from the Miller Bros., bringing the whole troupe from Oklahoma out to California via train. The show consisted of 300

The "Miller 101 Bison Ranch Studio", which the Millers dubbed "Inceville" (and was later re-christened "Triangle Ranch") was the first of its kind in that it featured silent stages, production offices, printing labs, a commissary large enough to serve lunch to hundreds of workers, dressing rooms, props houses, elaborate sets, and other necessities – all in one location. While the site was under construction, Ince also leased the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show from the Miller Bros., bringing the whole troupe from Oklahoma out to California via train. The show consisted of 300  When construction was completed, the streets were lined with many types of structures, from humble cottages to mansions, mimicking the style and architecture of different countries. Extensive outdoor western sets were built and used on the site for several years. According to Katherine La Hue in her book, ''Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea'':

When construction was completed, the streets were lined with many types of structures, from humble cottages to mansions, mimicking the style and architecture of different countries. Extensive outdoor western sets were built and used on the site for several years. According to Katherine La Hue in her book, ''Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea'':

By 1915, Ince was considered one of the best-known producer-directors. Around this time,

By 1915, Ince was considered one of the best-known producer-directors. Around this time,

For a while, Ince joined competitor

For a while, Ince joined competitor  In back of the impressive office building were approximately 40 buildings, most of which were designed in the

In back of the impressive office building were approximately 40 buildings, most of which were designed in the

Ince's death at the age of 44 has been the subject of much speculation and scandal, with rumors of murder, mystery, and jealousy. The official cause of his death was

Ince's death at the age of 44 has been the subject of much speculation and scandal, with rumors of murder, mystery, and jealousy. The official cause of his death was

Movie columnist

Movie columnist

"Peter Bogdanovich on Completing Orson Welles Long Awaited ''The Other Side of the Wind for Showtime''"

(March 9, 2008 interview). ''Wellesnet: The Orson Welles Web Resource'', March 14, 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2013 In Bogdanovich's film, Ince is portrayed by

File:Silver Sheet September 01 1920.pdf, ''The Silver Sheet'' (1920)

File:Silver Sheet December 01 1921.pdf, ''

File:The Battle of Gettysburg 1913 newpaperad.jpg, ''

Ince Theater, Culver City, California

Thomas H. Ince Papers, 1913–1964, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Thomas H. Ince Papers, 1907–1925, Museum of Modern Art, Film Study Center Special Collections, New York City

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ince, Thomas Harper 1880 births 1924 deaths Cinema pioneers American male screenwriters American male silent film actors American film production company founders American people of English descent Writers from Newport, Rhode Island Male actors from Rhode Island 20th-century American male actors Articles containing video clips Death conspiracy theories Film directors from Rhode Island Screenwriters from Rhode Island 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

with an employee from his old acting troupe, William S. Hart. Ince found his first film work as an actor for the Biograph Company, directed by his future partner, D.W. Griffith. Griffith was impressed enough with Ince to hire him as a production coordinator at Biograph. This led to more work coordinating productions at Carl Laemmle

Carl Laemmle (; born Karl Lämmle; January 17, 1867 – September 24, 1939) was a film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures. He produced or worked on over 400 films.

Regarded as one of the most important o ...

's Independent Motion Pictures Co. (IMP). That same year, a director at IMP was unable to complete work on a small feature film, so in a moment of bravado, Ince suggested that Laemmle hire him as a full-time director to complete the film. Impressed with the young man, Laemmle sent him to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

to make one-reel shorts with his new stars, Mary Pickford

Gladys Marie Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian-American stage and screen actress and producer with a career that spanned five decades. A pioneer in the US film industry, she co-founde ...

and Owen Moore, out of the reach of Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

's Motion Picture Patents Company

The Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC, also known as the Edison Trust), founded in December 1908 and terminated seven years later in 1915 after conflicts within the industry, was a trust of all the major US film companies and local foreign-bra ...

-—the trust that was attempting to crush all independent production companies and corner the market on film production. Ince's output, however, was small. Although he tackled many different subjects, he was strongly drawn to westerns and American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

dramas.

Clashes between the trust and independent films became exacerbated, so Ince moved to California to escape these pressures. He hoped to achieve the effects accomplished with minimal facilities like Griffith, which he believed, could only be accomplished in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

. After only a year with IMP, Ince quit. In September 1911, Ince walked into the offices of actor-financier Charles O. Baumann

Charles O. Baumann (January 20, 1874 – July 18, 1931) was an American film producer, film studio executive, and pioneer in the motion picture industry.

Biography Career

He was a partner in the Crescent Film Company formed in 1908 and in ...

(1874–1931) who co-owned the New York Motion Picture Company

The New York Motion Picture Company was a film production and distribution company from 1909 until 1914. It changed names to New York Picture Corporation in 1912. It released films through several different brand names, including 101 Bison, Kay ...

(NYMP) with actor-writer Adam Kessel, Jr. (1866–1946). Ince had found out that NYMPC had recently established a West Coast studio named Bison Studios at 1719 Alessandro (now known as Glendale Blvd.) in Edendale (present-day Echo Park) to make westerns and he wanted to direct those pictures.

''The offer came as a distinct shock, but I kept cool and concealed my excitement. I tried to convey the impression that he would have to raise the ante a trifle if he wanted me. That also worked, and I signed a contract for three months at $150 a week. Very soon after that, with Mrs. Ince, my cameraman, property man and Ethel Grandin, my leading woman, I turned my face westward.''Together with his young wife and a small entourage, Ince moved to Bison Studios to begin work immediately. He was shocked, however, to discover that the studio was nothing more than a "tract of land graced only by a four-room bungalow and a barn."

Inceville

Ince's aspirations soon led him to leave the narrow confines of Edendale and find a location that would give him greater scope and variety. He settled upon a tract of land called ''Bison Ranch'' located atSunset Blvd.

Sunset Boulevard is a boulevard in the central and western part of Los Angeles, California, that stretches from the Pacific Coast Highway in Pacific Palisades east to Figueroa Street in Downtown Los Angeles. It is a major thoroughfare in t ...

and Pacific Coast Highway in the Santa Monica Mountains

The Santa Monica Mountains is a coastal mountain range in Southern California, next to the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Transverse Ranges. Because of its proximity to densely populated regions, it is one of the most visited natural areas in ...

, (the present-day location of the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine) which he rented by the day. By 1912, he had earned enough money to purchase the ranch and was granted permission by NYMP to lease another in the Palisades Highlands stretching up Santa Ynez Canyon between Santa Monica

Santa Monica (; Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 U.S. Census population was 93,076. Santa Monica is a popular resort town, owing to i ...

and Malibu where Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

was eventually established, which was owned by The Miller Bros of Ponca City, Oklahoma

Ponca City ( iow, Chína Uhánⁿdhe) is a city in Kay County in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The city was named after the Ponca tribe. Ponca City had a population of 25,387 at the time of the 2010 census- and a population of 24,424 in the 2020 ...

. And it was here Ince built his first movie studio.

The "Miller 101 Bison Ranch Studio", which the Millers dubbed "Inceville" (and was later re-christened "Triangle Ranch") was the first of its kind in that it featured silent stages, production offices, printing labs, a commissary large enough to serve lunch to hundreds of workers, dressing rooms, props houses, elaborate sets, and other necessities – all in one location. While the site was under construction, Ince also leased the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show from the Miller Bros., bringing the whole troupe from Oklahoma out to California via train. The show consisted of 300

The "Miller 101 Bison Ranch Studio", which the Millers dubbed "Inceville" (and was later re-christened "Triangle Ranch") was the first of its kind in that it featured silent stages, production offices, printing labs, a commissary large enough to serve lunch to hundreds of workers, dressing rooms, props houses, elaborate sets, and other necessities – all in one location. While the site was under construction, Ince also leased the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show from the Miller Bros., bringing the whole troupe from Oklahoma out to California via train. The show consisted of 300 cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the '' vaqu ...

s and cowgirls; 600 horses, cattle and other livestock (including steers and bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

) and a whole Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota: /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The modern Sioux consist of two major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota and ...

tribe (200 of them in all) who set up their teepees on the property. They were then renamed "The Bison-101 Ranch Co.", and specialized in making westerns released under the name World Famous Features.

When construction was completed, the streets were lined with many types of structures, from humble cottages to mansions, mimicking the style and architecture of different countries. Extensive outdoor western sets were built and used on the site for several years. According to Katherine La Hue in her book, ''Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea'':

When construction was completed, the streets were lined with many types of structures, from humble cottages to mansions, mimicking the style and architecture of different countries. Extensive outdoor western sets were built and used on the site for several years. According to Katherine La Hue in her book, ''Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea'':

''Ince invested $35,000 in building, stages and sets ... a bit of Switzerland, aWhile the cowboys, Native Americans and assorted workmen lived at "Inceville", the main actors came fromPuritan The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...settlement, aJapan Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...ese village ... beyond the breakers, an ancientbrigantine A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts. Ol ...weighed anchor, cutlassed men swarming over the sides of the ship, while on the shore performing cowboys galloped about, twirling their lassos in pursuit of errant cattle ... The main herds were kept in the hills, where Ince also raised feed and garden produce. Supplies of every sort were needed to house and feed a veritable army of actors, directors and subordinates.''

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

and other communities as needed, taking the red trolley cars to the Long Wharf at Temescal Canyon, where buckboards conveyed them to the set.

Ince lived in a house overlooking the vast studio, later the location of Marquez Knolls. Here he functioned as the central authority over multiple production units, changing the way films were made by organizing production methods into a disciplined system of filmmaking. Indeed, "Inceville" became a prototype for Hollywood film studios of the future, with a studio head (Ince), producers, directors, production managers, production staff, and writers all working together under one organization (the unit system) and under the supervision of a General Manager, Fred J. Balshofer.

Before this, the director and cameraman

A camera operator, or depending on the context cameraman or camerawoman, is a professional operator of a film camera or video camera as part of a film crew. The term "cameraman" does not imply that a male is performing the task.

In filmmaki ...

controlled the production of the picture, but Ince put the producer in charge of the film from inception to final product. He defined the producer's role in both a creative and industrial sense. He was also one of the first to hire a separate screenwriter

A screenplay writer (also called screenwriter, scriptwriter, scribe or scenarist) is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media, such as films, television programs and video games, are based.

...

, director, and editor

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, photographic, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, or ...

(instead of the director doing everything themselves). By 1913, the concept of the production manager

In the cinema of the United States, a unit production manager (UPM) is the Directors Guild of America–approved title for the top below-the-line staff position, responsible for the administration of a feature film or television production. Non ...

had been created. With the aid of George Stout, an accountant for NYMP, Ince re-organized how films were outputted to bring discipline to the process. After this adjustment the studio's weekly output increased from one to two, and later three two-reel pictures per week, released under such names as "Kay-Bee" (Kessel-Baumann), "Domino" (comedy), and "Broncho" (western) productions. These were written, produced, cut, and assembled, with the finished product delivered within a week. By enabling more than one film to be made at a time, Ince decentralized the process of movie production to meet the increased demand from theaters. This was the dawning of the assembly-line system that all studios eventually adopted.

With this model, developed between 1913 and 1918, Ince gradually exercised even more control over the film production process as a director-general. In 1913 alone, he made over 150 two-reeler movies, mostly Westerns, thereby anchoring the popularity of the genre for decades. While many of Ince's films were praised in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, many American critics did not share this high opinion. One such picture was ''The Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

'' (1913) which was five reels long. The picture helped bring into vogue the idea of the feature-length film. Another important early movie for Ince was '' The Italian'' (1915), which depicted immigrant

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, ...

life in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Two of his most successful films were among his first, ''War on the Plains'' (1912) and ''Custer's Last Fight

''Custer's Last Fight'' (also known as ''Custer's Last Raid'') is a 1912 American silent short Western film. It is the first film about George Armstrong Custer and his final stand at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Francis Ford, the older ...

'' (1912), which featured many Native Americans who had actually been in the battle.

Even though he was the first producer-director and directed most of his early productions, by 1913 Ince eventually ceased full-time directing to concentrate on producing, transferring this responsibility to such proteges as Francis Ford and his brother John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

, Jack Conway, William Desmond Taylor

William Desmond Taylor (born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner, 26 April 1872 – 1 February 1922) was an Anglo-Irish-American film director and actor. A popular figure in the growing Hollywood motion picture colony of the 1910s and early 1920s, ...

, Reginald Barker, Fred Niblo, Henry King and Frank Borzage

Frank Borzage (; April 23, 1894 – June 19, 1962) was an Academy Award-winning American film director and actor, known for directing '' 7th Heaven'' (1927), '' Street Angel'' (1928), '' Bad Girl'' (1931), ''A Farewell to Arms'' (1932), '' Man's ...

. The story was the preeminent aspect of Ince's pictures. Films such as The Italian, The Gangsters and the Girl (1914), and The Clodhopper

''The Clodhopper'' is a 1917 American comedy drama film from Kay Bee Pictures starring Charles Ray and Margery Wilson and directed by Victor Schertzinger.

Plot

Isaac Nelson (French) is the tight-fisted president of a country bank and owns a far ...

(1917) are excellent examples of the dramatic structure that resulted from his masterful editing. Film preservationist David Shepard said of Ince in ''The American Film Heritage'':

Ince also discovered many talents, including his old actor friend, William S. Hart, who made some of the best early westerns, beginning in 1914. Later, a rift developed between the two over sharing of profits. Portentously, on January 16, 1916, a few days after the opening of his first Culver City

Culver City is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 40,779. Founded in 1917 as a "whites only" sundown town, it is now an ethnically diverse city with what was called the "third-most ...

studio, a fire broke out at "Inceville", the first of many that eventually destroyed all of the buildings.

Ince later gave up on the studio and sold it to Hart, who renamed it "Hartville." Three years later, Hart sold the lot to Robertson-Cole Pictures Corporation, which continued filming there until 1922. La Hue writes that "the place was virtually a ghost town when the last remnants of "Inceville" were burned on July 4, 1922, leaving only a "weatherworn old church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

, which stood sentinel over the charred ruins."

Ince-Triangle Studios

By 1915, Ince was considered one of the best-known producer-directors. Around this time,

By 1915, Ince was considered one of the best-known producer-directors. Around this time, real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

mogul Harry Culver noticed Ince shooting a western in Ballona Creek. Impressed with his talents, Culver convinced Ince to move from Inceville and re-locate to what was to become Culver City

Culver City is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 40,779. Founded in 1917 as a "whites only" sundown town, it is now an ethnically diverse city with what was called the "third-most ...

. Taking Culver's advice, Ince left NYMP and on July 19 partnered with D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett to form The Triangle Motion Picture Company based on their prestige as producers. Triangle (so named because from an aerial point of view the property had a triangular shape) was built at 10202 West Washington Boulevard (which became the Ince/Triangle Studios, before becoming Lot 1 of the prestigious MGM Studios, and is now Sony Pictures Studios

The Sony Pictures Studios is an American television and film studio complex located in Culver City, California at 10202 West Washington Boulevard and bounded by Culver Boulevard (south), Washington Boulevard (north), Overland Avenue (west) and ...

as a result the aftermath of Griffith's ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

.'' Although a box-office success, the film led to riots

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targeted ...

in major northern cities due to its controversial content.

Triangle was one of the first vertically integrated film companies. By combining production, distribution, and theater operations under one roof, the partners created the most dynamic studio in Hollywood. They attracted directors and stars of the day, including Pickford, Lillian Gish

Lillian Diana Gish (October 14, 1893February 27, 1993) was an American actress, director, and screenwriter. Her film-acting career spanned 75 years, from 1912, in silent film shorts, to 1987. Gish was called the "First Lady of American Cinema", ...

, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle (; March 24, 1887 – June 29, 1933) was an American silent film actor, comedian, director, and screenwriter. He started at the Selig Polyscope Company and eventually moved to Keystone Studios, where he worked w ...

, and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. They also produced some of the most enduring films of the silent era, including the Keystone Kops comedy franchise. Originally a distributor of films produced by NYMP, the Reliance Motion Picture Corp., Majestic Motion Picture Co., and The Keystone Film Co., by November 1916 the company's distribution was handled by Triangle Distributing Corporation.

Though Ince had many credits as a director at Triangle, he only supervised the production of most pictures, working primarily as executive producer. One of his important pictures as a director was ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

'' (1916), an epic plea for peace and American neutrality set in a mythical country and dedicated to the mothers of those who died in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The film competed with Griffith's famous epic, '' Intolerance'' and beat it at the box office

A box office or ticket office is a place where tickets are sold to the public for admission to an event. Patrons may perform the transaction at a countertop, through a hole in a wall or window, or at a wicket. By extension, the term is fre ...

. ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

'' was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Ince added a few stages and an administration building to Triangle Studios before selling his shares to Griffith and Sennett in 1918. Three years later, the studios were acquired by Goldwyn Pictures, and in 1924 the facility became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

studios. Although many believe that such classics as Gone with the Wind and King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

were later filmed on that same lot, those movies in fact had been shot at 9336 West Washington Blvd at the Thomas H. Ince Studios.

Thomas H. Ince Studios

For a while, Ince joined competitor

For a while, Ince joined competitor Adolph Zukor

Adolph Zukor (; hu, Zukor Adolf; January 7, 1873 – June 10, 1976) was a Hungarian-American film producer best known as one of the three founders of Paramount Pictures.Obituary '' Variety'' (June 16, 1976), p. 76. He produced one of America' ...

to form Paramount-Artcraft Pictures (later Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

). However, he yearned to go back to running his own studio. On July 19, 1918, following Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz; yi, שמואל געלבפֿיש; August 27, 1882 (claimed) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer. He was best known for being the founding contributor an ...

's acquisition of the Triangle lot, he purchased a 14-acre (57,000 m2) property at 9336 West Washington Blvd. on an option basis from Culver along with a $132,000 loan. Thus was formed Thomas H. Ince Studios, which operated from 1919 to 1924. (The area later known as RKO Forty Acres was southeast of the studio.) Ince Studios was to be another Culver City historic landmark. When Ince conceived the idea of building his own studio, he was determined to have it different from the others. Plans submitted to him by architects Meyer & Holler, included having a whole front administrative building made into a replica of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

's home at Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

. The resulting administration building, known as "The Mansion", was the first building on the lot.

In back of the impressive office building were approximately 40 buildings, most of which were designed in the

In back of the impressive office building were approximately 40 buildings, most of which were designed in the Colonial Revival

The Colonial Revival architectural style seeks to revive elements of American colonial architecture.

The beginnings of the Colonial Revival style are often attributed to the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which reawakened Americans to the archit ...

style. A small group of bungalows, built for various movie stars and designed in styles popular in the 1920s and '30s, were constructed on the west side of the lot. By 1920, two glass stages, a hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

, fire department, reservoir/swimming pool, and the back lot were completed. That same year, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

took a tour of the studios as did the King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

and Queen of Belgium, along with their son, Prince Leopold, among much pomp and ceremony.

Ince had two or three companies working continuously on the lot at any given time. According to film historian Marc Wanamaker, Ince worked with a team of eight directors but "he retained creative control of his films, developing the shooting scripts" and personally assembling each of his films. By now, Ince had drifted away from westerns in favor of social dramas and he made a few significant films including ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According to historian Paul Avrich, the ...

'' (1923), based on the play by Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earli ...

, and ''Human Wreckage

''Human Wreckage'' is a 1923 American independent silent drama propaganda film that starred Dorothy Davenport and featured James Kirkwood, Sr., Bessie Love, and Lucille Ricksen. The film was co-produced by Davenport and Thomas H. Ince and d ...

'' (1923), which was an early anti-drug film starring Dorothy Davenport

Fannie Dorothy Davenport (March 13, 1895 – October 12, 1977) was an American actress, screenwriter, film director, and producer.

Born into a family of film performers, Davenport had her own independent career before her marriage to the film a ...

(widow of addicted star Wallace Reid

William Wallace Halleck Reid (April 15, 1891 – January 18, 1923) was an American actor in silent film, referred to as "the screen's most perfect lover". He also had a brief career as a racing driver.

Early life

Reid was born in St. Louis, M ...

).

Although Ince found distribution for his films through Paramount and MGM, he was no longer as powerful as he once had been and tried to regain his status in Hollywood. In 1919, with several other independent entrepreneurs (notably his old partner at Triangle, Mack Sennett, Marshall Neilan

Marshall Ambrose "Mickey" Neilan (April 11, 1891 – October 27, 1958) was an American actor.

Early life

Born in San Bernardino, California, Neilan was known by most as "Mickey." Following the death of his father, the eleven-year-old Mickey ...

, Allan Dwan

Allan Dwan (born Joseph Aloysius Dwan; April 3, 1885 – December 28, 1981) was a pioneering Canadian-born American motion picture director, producer, and screenwriter.

Early life

Born Joseph Aloysius Dwan in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Dwan, wa ...

and Maurice Tourneur Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

*Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and L ...

) he co-founded the independent releasing company, Associated Producers, Inc., to distribute their films. However, Associated Producers merged with First National in 1922.

Though Ince still made some significant motion pictures, the studio system was starting to take over Hollywood. With little room for an independent producer and despite his attempts, Ince could not regain the powerful standing he once held in the industry. He and other independent producers tried to form the Cinematic Finance Corporation in 1921, which made loans to producers who already had been successful, but only accomplished its goal in a limited sense.

In 1925, a year after Ince's death, the studio was sold (with Pathé America) to Ince's friend Cecil B. DeMille. Besides DeMille, among those who had offices on the lot were producer Howard Hughes

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. (December 24, 1905 – April 5, 1976) was an American business magnate, record-setting pilot, engineer, film producer, and philanthropist, known during his lifetime as one of the most influential and richest people in t ...

and Selznick International Pictures. About four years later, DeMille sold his interest to Pathé and the studio became known as the Pathé Culver City Studio. By 1928 after mergers, the studio became RKO/Pathé. By 1957, a number of other studios followed: Desilu Culver, Culver City Studios, Laird International Studios, etc.

In 1991, Sony Pictures Entertainment

Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Sony Pictures or SPE, and formerly known as Columbia Pictures Entertainment, Inc.) is an American diversified multinational mass media and entertainment studio Conglomerate (company), conglom ...

purchased the property as the home for its television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

endeavors, renaming it Culver Studios, and eventually selling it in 2004 to a group of investors; the street intersecting the studios was renamed Ince Blvd. The studio is still home to Brooksfilms today.

Death

Ince's death at the age of 44 has been the subject of much speculation and scandal, with rumors of murder, mystery, and jealousy. The official cause of his death was

Ince's death at the age of 44 has been the subject of much speculation and scandal, with rumors of murder, mystery, and jealousy. The official cause of his death was heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

, and while witnesses (including his widow Nell) corroborate that his medical condition brought about his death, rumors and sensationalism continued decades later, fueled with the 2001 release of the movie ''The Cat's Meow

''The Cat's Meow'' is a 2001 historical drama film directed by Peter Bogdanovich, and starring Kirsten Dunst, Eddie Izzard, Edward Herrmann, Cary Elwes, Joanna Lumley, and Jennifer Tilly. The screenplay by Steven Peros is based on his 1997 play ...

''.

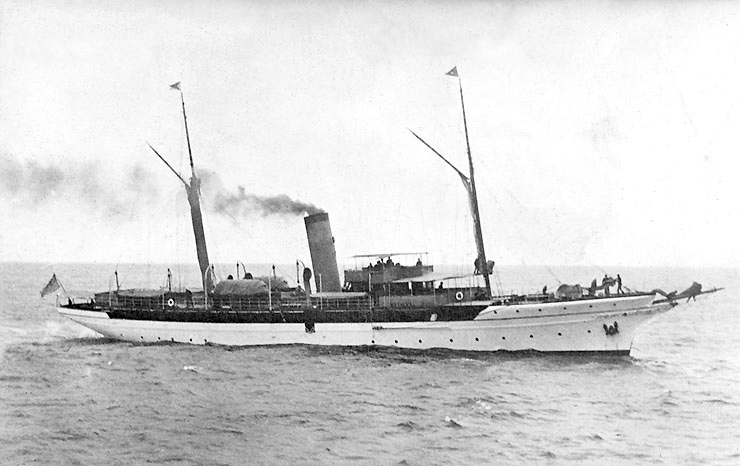

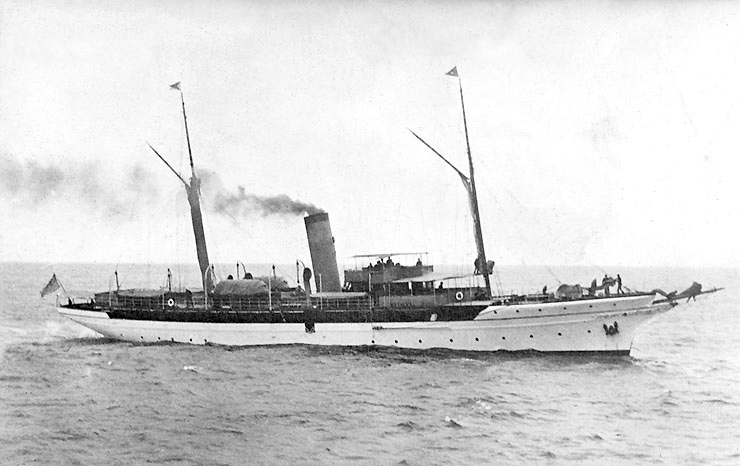

Ince and William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

had been negotiating a deal under which Hearst's Cosmopolitan Productions Cosmopolitan Productions, also often referred to as Cosmopolitan Pictures, was an American film company based in New York City from 1918 to 1923 and Hollywood until 1938.

History

Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst formed Cosmopolitan in co ...

would use Ince's studio. Hearst visited Ince at his home, his "Dias Dorados" estate at 1051 Benedict Canyon Drive, on Saturday November 15 and invited him for a weekend cruise on his yacht to honor Ince's birthday and to work out details of the Ince/Cosmopolitan deal.

According to Ince's widow, Nell, Ince took a train to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, where he joined the guests the next morning. At dinner that Sunday night, the group celebrated his birthday but later Ince suffered an acute bout of indigestion

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier t ...

due to his consumption of salted almonds and champagne, both forbidden as he had peptic ulcers

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines i ...

. Accompanied by Dr. Goodman, a licensed though non-practicing physician, Ince traveled by train to Del Mar, where he was taken to a hotel and given medical treatment by a second doctor and a nurse. Ince then summoned his wife and Dr. Ida Cowan Glasgow (Ince's personal physician) to Del Mar with Ince's eldest son William accompanying them. The group traveled by train to his Los Angeles home where Ince died. Nell said that Ince had been treated for chest pains caused by angina

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of obstr ...

, but years later his son William became a physician and said that his father's illness resembled thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (th ...

.

Dr. Glasgow signed the death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

citing heart failure as the cause of death. The front page of the Wednesday morning ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' supposedly sensationalized the story: '"Movie Producer Shot on Hearst Yacht!", but the headlines vanished in the evening edition. On November 20, the ''Los Angeles Times'' published Ince's obituary citing heart disease as the cause of death along with his failing health from an automobile accident two years earlier. A month later, the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' reported that the San Diego District Attorney announced that Ince's death was caused by heart failure and no further investigation was necessary. Both Ince and his wife were practicing Theosophists who preferred cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a Cadaver, dead body through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India ...

and had arranged for it long before Ince's death. While rumors prevailed that Ince's widow suddenly departed the country after her husband's death, she actually left for Europe about seven months later in July 1925.

However, several conflicting stories circulated about the incident, often revolving around a claim that Hearst shot Ince in the head after mistaking him for Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is conside ...

. Chaplin's valet, Toraichi Kono, claimed to have seen Ince when he came ashore via stretcher in San Diego. Kono told his wife that Ince's head was "bleeding from a bullet wound." The story quickly spread among Japanese domestic workers throughout Beverly Hills

Beverly Hills is a city located in Los Angeles County, California. A notable and historic suburb of Greater Los Angeles, it is in a wealthy area immediately southwest of the Hollywood Hills, approximately northwest of downtown Los Angeles. ...

. Charles Lederer, the nephew of Hearst's longtime partner Marion Davies

Marion Davies (born Marion Cecilia Douras; January 3, 1897 – September 22, 1961) was an American actress, producer, screenwriter, and philanthropist. Educated in a religious convent, Davies fled the school to pursue a career as a chorus girl ...

, also told a similar story to Peter Bogdanovich

Peter Bogdanovich (July 30, 1939 – January 6, 2022) was an American director, writer, actor, producer, critic, and film historian.

One of the " New Hollywood" directors, Bogdanovich started as a film journalist until he was hired to work on ...

, the director of ''The Cat's Meow''. Elinor Glyn

Elinor Glyn ( Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern stan ...

, who was on the yacht, told Eleanor Boardman

Olive Eleanor Boardman (August 19, 1898 – December 12, 1991) was an American film actress of the silent era.

Early life and career

Olive Eleanor Boardman was born on August 19, 1898, the youngest child to George W. Boardman and Janice Merriam ...

that everyone aboard the yacht had been sworn to secrecy about the events, which would indicate more than a death under natural circumstances. But during Ince's funeral, the ''Los Angeles Times'' noted that his casket would remain open for one hour "to afford friends and studio employees to pass for one last glimpse of the man they loved and respected", with no witnesses ever mentioning a bullet wound. Ince's body was cremated on November 21 in Hollywood Forever Cemetery

Hollywood Forever Cemetery is a full-service cemetery, funeral home, crematory, and cultural events center which regularly hosts community events such as live music and summer movie screenings. It is one of the oldest cemeteries in Los Angel ...

and the ashes returned to his family on December 24, 1924 who reportedly scattered them at sea.

Movie columnist

Movie columnist Louella Parsons

Louella Parsons (born Louella Rose Oettinger; August 6, 1881 – December 9, 1972) was an American movie columnist and a screenwriter. She was retained by William Randolph Hearst because she had championed Hearst's mistress Marion Davies and s ...

' name also figured into the Ince scandal, with some speculating that she had been aboard the ''Oneida'' that fatal day. When the ''Oneida'' sailed, Parsons was a New York movie columnist for one of Hearst's papers. Supposedly, after the Ince affair, Hearst gave her a lifetime contract and expanded her syndication

Syndication may refer to:

* Broadcast syndication, where individual stations buy programs outside the network system

* Print syndication, where individual newspapers or magazines license news articles, columns, or comic strips

* Web syndication, ...

. However, other sources show that Parsons did not gain her position with Hearst as part of "hush money" but had been the motion picture editor of the Hearst-owned ''New York American'' in December 1923 and her contract was signed a year before Ince's death. Another story circulated that Hearst provided Nell Ince with a trust fund just before she left for Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and that Hearst paid off Ince's mortgage on his Château Élysée apartment building in Hollywood. But Nell was left a very wealthy woman and the Château Élysée was an apartment she had already owned and had built on the grounds where the Ince home once stood.

Years later, Hearst spoke to a journalist about the rumor that he had murdered Tom Ince. "Not only am I innocent of this Ince murder," he said, "So is everybody else." Nell Ince herself was increasingly frustrated over the Hearst rumors surrounding her husband's death and remarked: "Do you think I would have done nothing if I even suspected that my husband had been victim of foul play on anyone's part?"

But the myth of Ince's death overshadowed his reputation as a pioneering filmmaker and his role in the growth of the film industry. His studio was sold soon after he died. His final film, ''Enticement

''Enticement'' is a 1925 American silent drama film directed by George Archainbaud and starring Mary Astor, Clive Brook, and Ian Keith.

Plot

As described in a review in a film magazine, Leonore Bewlay (Astor), recently grown into womanhood, wh ...

'', a romance set in the French Alps

The French Alps are the portions of the Alps mountain range that stand within France, located in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur regions. While some of the ranges of the French Alps are entirely in France, others, such as ...

, was released posthumously in 1925.

In popular culture

''Murder at San Simeon'' ( Scribner), a 1996 novel byPatricia Hearst

Patricia is a female given name of Latin origin. Derived from the Latin word '' patrician'', meaning "noble"; it is the feminine form of the masculine given name Patrick. The name Patricia was the second most common female name in the United S ...

(William Randolph's granddaughter) and Cordelia Frances Biddle, is a mystery based on the 1924 death of producer Thomas Ince aboard the yacht of William Randolph Hearst. This fictitious version presents Chaplin and Davies as lovers and Hearst as the jealous old man unwilling to share his mistress.

'' RKO 281'' is a 1999 film about the making of ''Citizen Kane

''Citizen Kane'' is a 1941 American drama film produced by, directed by, and starring Orson Welles. He also co-wrote the screenplay with Herman J. Mankiewicz. The picture was Welles' first feature film. ''Citizen Kane'' is frequently cited ...

''. The movie includes a scene depicting screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz telling director Orson Welles his account of the incident.

''The Cat's Meow

''The Cat's Meow'' is a 2001 historical drama film directed by Peter Bogdanovich, and starring Kirsten Dunst, Eddie Izzard, Edward Herrmann, Cary Elwes, Joanna Lumley, and Jennifer Tilly. The screenplay by Steven Peros is based on his 1997 play ...

'', the 2001 film directed by Peter Bogdanovich

Peter Bogdanovich (July 30, 1939 – January 6, 2022) was an American director, writer, actor, producer, critic, and film historian.

One of the " New Hollywood" directors, Bogdanovich started as a film journalist until he was hired to work on ...

, is another fictitious version of Ince's death. Bogdanovich notes that he heard the story from director Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

, who said he heard it from screenwriter Charles Lederer (Marion Davies's nephew).French, Lawrence"Peter Bogdanovich on Completing Orson Welles Long Awaited ''The Other Side of the Wind for Showtime''"

(March 9, 2008 interview). ''Wellesnet: The Orson Welles Web Resource'', March 14, 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2013 In Bogdanovich's film, Ince is portrayed by

Cary Elwes

Ivan Simon Cary Elwes (; born 26 October 1962) is an English actor and writer. He is known for his leading film roles as Westley in ''The Princess Bride'' (1987), Robin Hood in '' Robin Hood: Men in Tights'' (1993), and Dr. Lawrence Gordon in ...

. The movie was adapted by Steven Peros

Steven Peros is an American playwright, director and screenwriter of film and television. He is the author of both the stage play and screenplay for ''The Cat's Meow'', which was made into the 2002 Lionsgate film directed by Peter Bogdanovich an ...

from his own play, which premiered in Los Angeles in 1997.

Ince's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

is located at 6727 Hollywood Blvd. in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

.

The Silver Sheet

A studio publication promoting ''Thomas H. Ince Productions''.Hail the Woman

''Hail the Woman'' is a 1921 American silent drama film directed by John Griffith Wray. Produced by Thomas Ince, it stars Florence Vidor as a woman who takes a stand against the hypocrisy of her father and brother, played by Theodore Roberts a ...

'' (1921)

File:Silver Sheet September 01 1922.pdf, '' Skin Deep'' (1922)

File:Silver Sheet October 01 1922.pdf, ''Lorna Doone

''Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor'' is a novel by English author Richard Doddridge Blackmore, published in 1869. It is a romance based on a group of historical characters and set in the late 17th century in Devon and Somerset, particularly ar ...

'' (1922)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1923.pdf, ''Scars of Jealousy

''Scars of Jealousy'' is a 1923 American silent drama film directed by Lambert Hillyer and starring Lloyd Hughes and Frank Keenan. It was produced by Thomas H. Ince and distributed through Associated First National, later First National.

Cast

...

'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1923 - BELL BOY 13.pdf, ''Bell Boy 13

''Bell Boy 13'' is a 1923 American silent comedy film directed by William A. Seiter, and starring Douglas MacLean, John Steppling, Margaret Loomis, William Courtright, Emily Gerdes, and Eugene Burr. The film was released by First National Pictu ...

'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1923 - GALLOPING FISH.pdf, ''The Galloping Fish

''The Galloping Fish'' is a 1924 American silent comedy film directed by Del Andrews and starring Louise Fazenda, Syd Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Chester Conklin, Lucille Ricksen, and John Steppling. It is based on the 1917 novel ''Friend Wife'' ...

'' (1924)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1923 - SOUL OF THE BEAST.pdf, ''Soul of the Beast

''Soul of the Beast'' is a 1923 American silent romantic drama film directed by John Griffith Wray and starring Madge Bellamy, Cullen Landis, and Noah Beery

Noah Nicholas Beery (January 17, 1882 – April 1, 1946) was an American actor ...

'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1923 - ANNA CHRISTIE.pdf, ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According to historian Paul Avrich, the ...

'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet February 01 1923 - WHAT A WIFE LEARNED.pdf, '' What a Wife Learned'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet May 01 1923 - MAN OF ACTION.pdf, '' A Man of Action'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet May 01 1923 - HER REPUTATION.pdf, '' Her Reputation'' (1923)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1924 - CHRISTINE OF THE HUNGRY HEART.pdf, '' Christine of the Hungry Heart'' (1924)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1924 - IDLE TONGUES.pdf, ''Idle Tongues

''Idle Tongues'' is a 1924 American silent drama film directed by Lambert Hillyer and produced by Thomas H. Ince, one of his last efforts before his death that year. It starred Percy Marmont and Doris Kenyon and was distributed by First National ...

'' (1924)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1924 - MARRIAGE CHEAT.pdf, ''The Marriage Cheat

''The Marriage Cheat'' is a 1924 American silent drama film directed by John Griffith Wray and written by C. Gardner Sullivan. The film stars Leatrice Joy, Adolphe Menjou, Percy Marmont, Laska Winter, Henry A. Barrows, and J. P. Lockney. The ...

'' (1924)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1924 - ENTICEMENT.pdf, ''Enticement

''Enticement'' is a 1925 American silent drama film directed by George Archainbaud and starring Mary Astor, Clive Brook, and Ian Keith.

Plot

As described in a review in a film magazine, Leonore Bewlay (Astor), recently grown into womanhood, wh ...

'' (1925)

File:Silver Sheet April 01 1924 - THOSE WHO DANCE.pdf, '' Those Who Dance'' (1924)

File:Silver Sheet January 01 1925 - PLAYING WITH SOULS.pdf, '' Playing with Souls'' (1925)

Filmography, posters and newspaper ads

:''see Thomas H. Ince filmography''The Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the ...

'' (1913)

File:The Wrath of the Gods poster.jpg, '' The Wrath of the Gods'' (1914)

File:TheItalian-moviepamphlet-1915.jpg, '' The Italian'' (1915)

File:The Return of Draw Egan poster.jpg, ''The Return of Draw Egan

''The Return of Draw Egan'' is a 1916 American silent Western film starring William S. Hart, Louise Glaum, Margery Wilson, Robert McKim, and J.P. Lockney.

Directed by William S. Hart and produced by Thomas H. Ince for Kay-Bee Pictures and th ...

'' (1916)

File:The Phantom 1916.jpg, ''The Phantom'' (1916)

File:Triangle Keystone.jpg, Triangle-Keystone comedies (1916)

File:Aryan poster.jpg, ''The Aryan

''The Aryan'' is a 1916 American silent Western film starring William S. Hart, Gertrude Claire, Charles K. French, Louise Glaum, and Bessie Love.

Directed by William S. Hart and produced by Thomas H. Ince, the screenplay was written by C. ...

'' (1916)

File:Civilization Poster.jpg, ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

'' (1916)

File:Civilization (1916) - Peace Song.jpg, ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

Peace Song'' (1916)

File:Civilization.jpg, ''Civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

'' (1916)

File:Hell's Hinges.jpg, ''Hell's Hinges

''Hell's Hinges'' is a 1916 American silent Western film starring William S. Hart and Clara Williams. Directed by Charles Swickard, William S. Hart and Clifford Smith, and produced by Thomas H. Ince, the screenplay was written by C. Gardner ...

'' (1916)

File:Alohaoe-newspaperad-1916.jpg, '' Aloha Oe'' (1916)

File:Giblyn-charles-peggy-1916-lobbycardposter.jpg, '' Peggy'' (1916)

False to the Finish.jpg, ''False to the Finish'' (1917)

Haunted by Himself.jpg, ''Haunted by Himself'' (1917)

Her Busted Debut.jpg, ''Her Busted Debut'' (1917)

Mystic Faces.jpg, ''Mystic Faces'' (1918)

File:Wagon Tracks 1919 film.jpg, ''Wagon Tracks

''Wagon Tracks'' is a 1919 American silent Western film written by C. Gardner Sullivan, produced by Thomas H. Ince and William S. Hart, and directed by Lambert Hillyer. Upon its release, the ''Los Angeles Times'' described it as Hollywood's g ...

'' (1919)

Child of M'sieu.jpg, ' (1919)

File:Silk Hosiery (1920) - 1.jpg, ''Silk Hosiery

''Silk Hosiery'' is a 1920 American silent comedy film directed by Fred Niblo and starring Enid Bennett. A print listed as being in nitrate exists in the Library of Congress and another in the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Plot

As summari ...

'' (1920)

File:Herhusbandsfriend-1921-newspaperad.jpg, '' Her Husband's Friend'' (1921)

File:Lorna Doone Poster.jpg, ''Lorna Doone

''Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor'' is a novel by English author Richard Doddridge Blackmore, published in 1869. It is a romance based on a group of historical characters and set in the late 17th century in Devon and Somerset, particularly ar ...

'' (1922)

Notes

References

* * * * * *External links

*Ince Theater, Culver City, California

Thomas H. Ince Papers, 1913–1964, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Thomas H. Ince Papers, 1907–1925, Museum of Modern Art, Film Study Center Special Collections, New York City

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ince, Thomas Harper 1880 births 1924 deaths Cinema pioneers American male screenwriters American male silent film actors American film production company founders American people of English descent Writers from Newport, Rhode Island Male actors from Rhode Island 20th-century American male actors Articles containing video clips Death conspiracy theories Film directors from Rhode Island Screenwriters from Rhode Island 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters