Sir George Stokes, 1st Baronet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

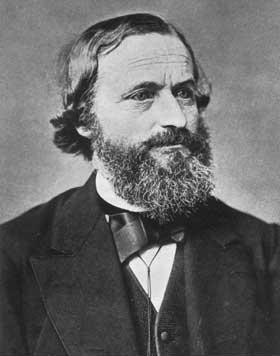

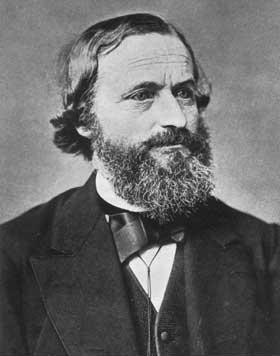

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet, (; 13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903) was an

In scope, his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede Lecture of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

In scope, his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede Lecture of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

Stokes's work on fluid motion and

Stokes's work on fluid motion and

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of

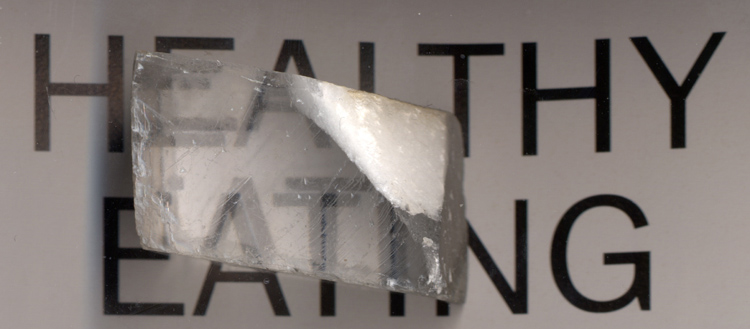

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarised light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarisation. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar, transparent

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarised light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarisation. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar, transparent

In other areas of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in

In other areas of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at  These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of

These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of

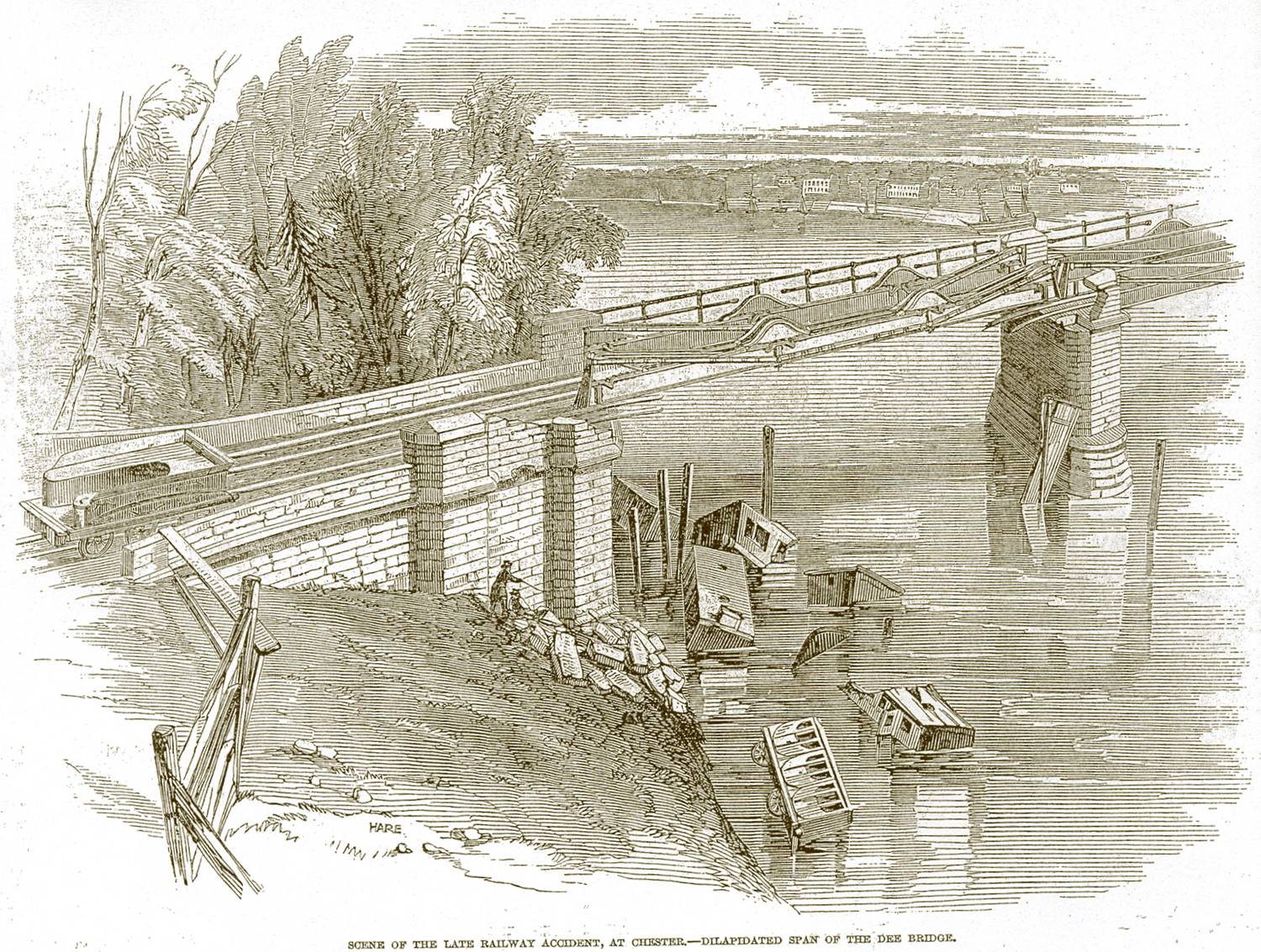

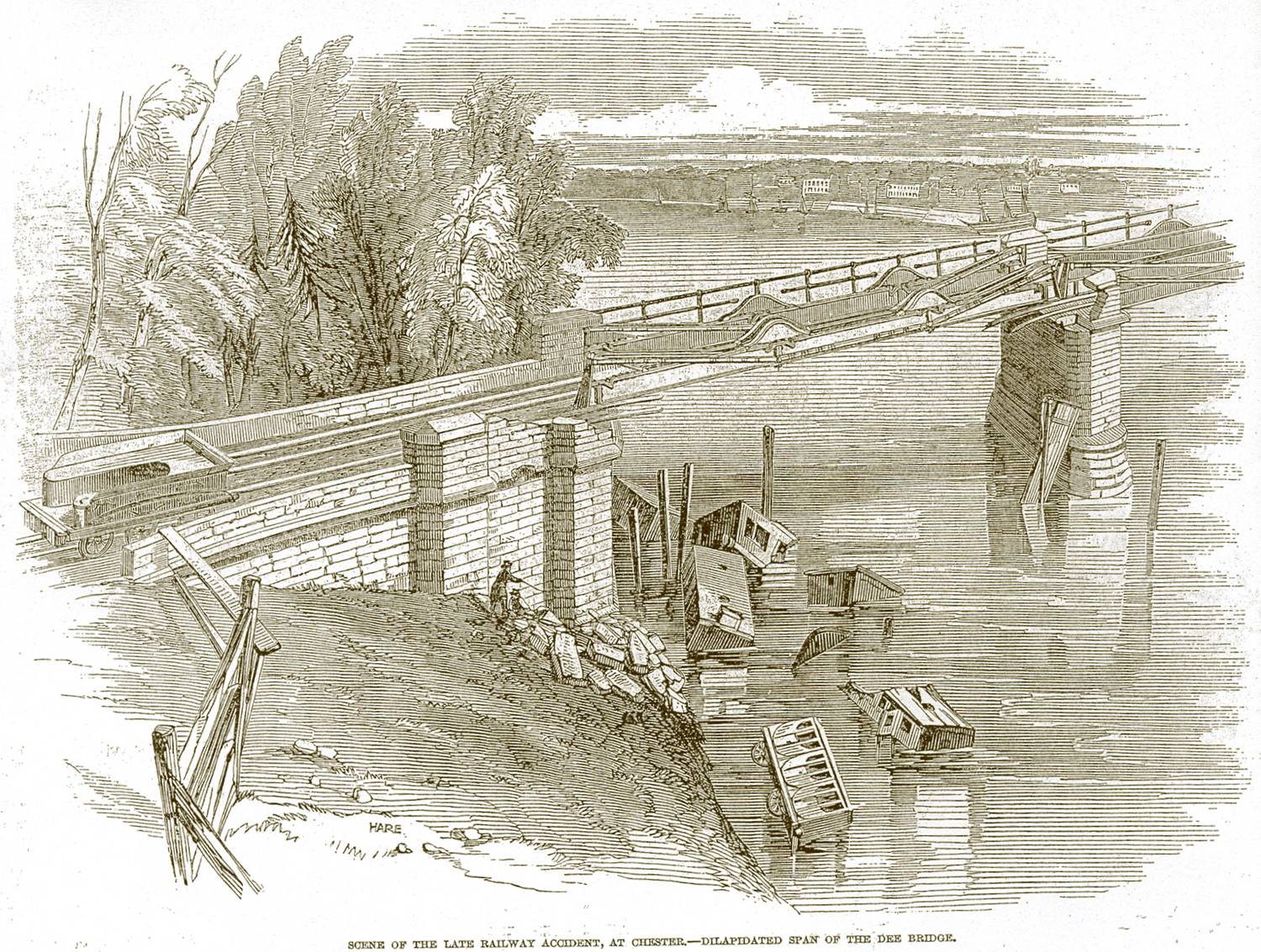

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee Bridge disaster in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains.

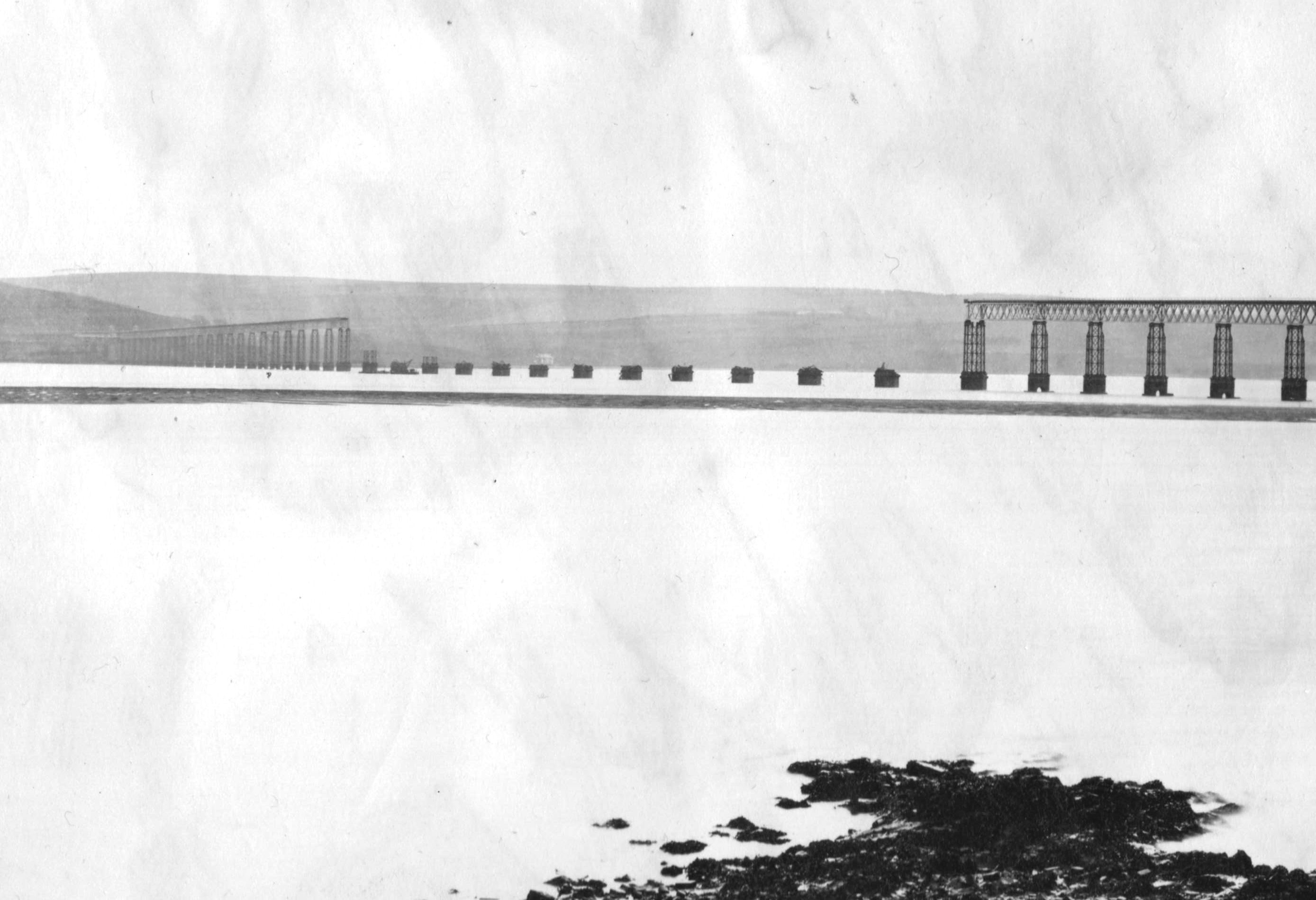

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee Bridge disaster in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains.  He appeared as an expert witness at the Tay Bridge disaster, where he gave evidence about the effects of wind loads on the bridge. The centre section of the bridge (known as the High Girders) was completely destroyed during a storm on 28 December 1879, while an express train was in the section, and everyone aboard died (more than 75 victims). The Board of Inquiry listened to many expert witnesses, and concluded that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained".

As a result of his evidence, he was appointed a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the effect of wind pressure on structures. The effects of high winds on large structures had been neglected at that time, and the commission conducted a series of measurements across Britain to gain an appreciation of wind speeds during storms, and the pressures they exerted on exposed surfaces.

He appeared as an expert witness at the Tay Bridge disaster, where he gave evidence about the effects of wind loads on the bridge. The centre section of the bridge (known as the High Girders) was completely destroyed during a storm on 28 December 1879, while an express train was in the section, and everyone aboard died (more than 75 victims). The Board of Inquiry listened to many expert witnesses, and concluded that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained".

As a result of his evidence, he was appointed a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the effect of wind pressure on structures. The effects of high winds on large structures had been neglected at that time, and the commission conducted a series of measurements across Britain to gain an appreciation of wind speeds during storms, and the pressures they exerted on exposed surfaces.

Stokes generally held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, he became president of the

Stokes generally held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, he became president of the

*

*DCU names three buildings after inspiring women scientists

Raidió Teilifís Éireann, 5 July 2017

''Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879''

Tempus (2004). * *PR Lewis, ''Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847'', Tempus Publishing (2007) *

George Gabriel Stokes: Life, Science and Faith

' Edited by Mark McCartney, Andrew Whitaker, and Alastair Wood, Oxford University Press, 2019.

* (1907), ed. by J. Larmor * Mathematical and physical paper

volume 1

an

volume 2

from the

volumes 1 to 5

from the University of Michigan Digital Collection.

Life and work of Stokes

''Natural Theology''

(1891), Adam and Charles Black. (1891–93 Gifford Lectures) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stokes, George Gabriel 1819 births 1903 deaths People from County Sligo 19th-century Anglo-Irish people Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Fellows of Pembroke College, Cambridge Masters of Pembroke College, Cambridge Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Irish mathematicians Irish physicists British physicists Optical physicists 19th-century British mathematicians Fluid dynamicists Irish Anglicans Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for the University of Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences UK MPs 1886–1892 Viscosity Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Senior Wranglers

Irish English

Hiberno-English (from Latin language, Latin ''Hibernia'': "Ireland"), and in ga, Béarla na hÉireann. or Irish English, also formerly Anglo-Irish, is the set of English dialects native to the island of Ireland (including both the Repub ...

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

. Born in County Sligo

County Sligo ( , gle, Contae Shligigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the Border Region and is part of the province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in the county. Sligo County Council is the local ...

, Ireland, Stokes spent all of his career at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of P ...

from 1849 until his death in 1903. As a physicist, Stokes made seminal contributions to fluid mechanics

Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the mechanics of fluids ( liquids, gases, and plasmas) and the forces on them.

It has applications in a wide range of disciplines, including mechanical, aerospace, civil, chemical and ...

, including the Navier–Stokes equations; and to physical optics

In physics, physical optics, or wave optics, is the branch of optics that studies interference, diffraction, polarization, and other phenomena for which the ray approximation of geometric optics is not valid. This usage tends not to include ef ...

, with notable works on polarization and fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, tha ...

. As a mathematician, he popularised "Stokes' theorem

Stokes's theorem, also known as the Kelvin–Stokes theorem Nagayoshi Iwahori, et al.:"Bi-Bun-Seki-Bun-Gaku" Sho-Ka-Bou(jp) 1983/12Written in Japanese)Atsuo Fujimoto;"Vector-Kai-Seki Gendai su-gaku rekucha zu. C(1)" :ja:培風館, Bai-Fu-Kan( ...

" in vector calculus

Vector calculus, or vector analysis, is concerned with differentiation and integration of vector fields, primarily in 3-dimensional Euclidean space \mathbb^3. The term "vector calculus" is sometimes used as a synonym for the broader subjec ...

and contributed to the theory of asymptotic expansions. Stokes, along with Felix Hoppe-Seyler, first demonstrated the oxygen transport function of hemoglobin and showed color changes produced by aeration of hemoglobin solutions.

Stokes was made a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

by the British monarch in 1889. In 1893 he received the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

, then the most prestigious scientific prize in the world, "for his researches and discoveries in physical science". He represented Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 65 ...

from 1887 to 1892, sitting as a Conservative. Stokes also served as president of the Royal Society from 1885 to 1890 and was briefly the Master of Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

.

Biography

George Stokes was the youngest son of the Reverend Gabriel Stokes (died 1834), a clergyman in theChurch of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

who served as rector of Skreen

Skreen () is a small village and parish in County Sligo, Ireland.

History

St Adomnán, the first biographer of St Columba (Colmcille) and one of his successors at Iona, first served as abbot at Skreen Abbey, which allegedly acquired its nam ...

in County Sligo

County Sligo ( , gle, Contae Shligigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the Border Region and is part of the province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in the county. Sligo County Council is the local ...

, and his wife Elizabeth Haughton, daughter of the Reverend John Haughton. Stokes' home life was strongly influenced by his father's evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

Protestantism: three of his brothers entered the Church, of whom the most eminent was John Whitley Stokes, Archdeacon of Armagh. John and George were always close, and George lived with John while attending school in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

. Of all his family he was closest to his sister Elizabeth. Their mother was remembered in the family as "beautiful but very stern". After attending schools in Skreen, Dublin and Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, in 1837 Stokes matriculated at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

. Four years later he graduated as senior wrangler and first Smith's prizeman, achievements that earned him election as a fellow of the college. In accordance with the college statutes, Stokes had to resign the fellowship when he married in 1857. Twelve years later, under new statutes, he was re-elected to the fellowship and he retained that place until 1902, when on the day before his 83rd birthday, he was elected as the college's Master. Stokes did not hold that position for long, for he died at Cambridge on 1 February the following year, and was buried in the Mill Road cemetery. There is also a memorial to him in the north aisle at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Career

In 1849, Stokes was appointed to the Lucasian professorship of mathematics at Cambridge, a position he held until his death in 1903. On 1 June 1899, the jubilee of this appointment was celebrated there in a ceremony attended by numerous delegates from European and American universities. A commemorative gold medal was presented to Stokes by the chancellor of the university and marble busts of Stokes by Hamo Thornycroft were formally offered to Pembroke College and to the university by Lord Kelvin. Stokes, who was made a baronet in 1889, further served his university by representing it in parliament from 1887 to 1892 as one of the two members for the Cambridge University constituency. In 1885–1890 he was also president of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, of which he had been one of the secretaries since 1854. Since he was also Lucasian Professor at this time, Stokes was the first person to hold all three positions simultaneously; Newton held the same three, although not at the same time.

Stokes was the oldest of the trio of natural philosophers, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

and Lord Kelvin being the other two, who especially contributed to the fame of the Cambridge school of mathematical physics in the middle of the 19th century. Stokes's original work began about 1840, and is distinguished for its quantity and quality. The Royal Society's catalogue of scientific papers gives the titles of over a hundred memoirs by him published down to 1883. Some of these are only brief notes, others are short controversial or corrective statements, but many are long and elaborate treatises.

Contributions to science

In scope, his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede Lecture of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

In scope, his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede Lecture of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

Fluid dynamics

Stokes's first published papers, which appeared in 1842 and 1843, were on the steady motion of incompressible fluids and some cases of fluid motion. These were followed in 1845 by one on the friction of fluids in motion and the equilibrium and motion of elastic solids, and in 1850 by another on the effects of the internal friction of fluids on the motion ofpendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward th ...

s. To the theory of sound he made several contributions, including a discussion of the effect of wind on the intensity of sound and an explanation of how the intensity is influenced by the nature of the gas in which the sound is produced. These inquiries together put the science of fluid dynamics

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids— liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including ''aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) a ...

on a new footing, and provided a key not only to the explanation of many natural phenomena, such as the suspension of clouds in air, and the subsidence of ripples and waves in water, but also to the solution of practical problems, such as the flow of water in rivers and channels, and the skin resistance of ships.

Creeping flow

viscosity

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the int ...

led to his calculating the terminal velocity for a sphere falling in a viscous medium. This became known as Stokes' law. He derived an expression for the frictional force (also called drag force) exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers.

His work is the basis of the falling sphere viscometer, in which the fluid is stationary in a vertical glass tube. A sphere of known size and density is allowed to descend through the liquid. If correctly selected, it reaches terminal velocity, which can be measured by the time it takes to pass two marks on the tube. Electronic sensing can be used for opaque fluids. Knowing the terminal velocity, the size and density of the sphere, and the density of the liquid, Stokes's law can be used to calculate the viscosity of the fluid. A series of steel ball bearing

A ball bearing is a type of rolling-element bearing that uses balls to maintain the separation between the bearing races.

The purpose of a ball bearing is to reduce rotational friction and support radial and axial loads. It achieves this ...

s of different diameter is normally used in the classic experiment to improve the accuracy of the calculation. The school experiment uses glycerine

Glycerol (), also called glycerine in British English and glycerin in American English, is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is sweet-tasting and non-toxic. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids know ...

as the fluid, and the technique is used industrially to check the viscosity of fluids used in processes.

The same theory explains why small water droplets (or ice crystals) can remain suspended in air (as clouds) until they grow to a critical size and start falling as rain (or snow and hail

Hail is a form of solid precipitation. It is distinct from ice pellets (American English "sleet"), though the two are often confused. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailstone. Ice pellets generally fal ...

). Similar use of the equation can be made in the settlement of fine particles in water or other fluids.

The CGS unit of kinematic viscosity was named " stokes" in recognition of his work.

Light

Perhaps his best-known researches are those which deal with the wave theory of light. His optical work began at an early period in his scientific career. His first papers on the aberration of light appeared in 1845 and 1846, and were followed in 1848 by one on the theory of certain bands seen in thespectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of colors ...

.

In 1849 he published a long paper on the dynamical theory of diffraction, in which he showed that the plane of polarisation must be perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Two years later he discussed the colours of thick plates.

Stokes also investigated George Airy's mathematical description of rainbows. Airy's findings involved an integral that was awkward to evaluate. Stokes expressed the integral as a divergent series, which were little understood. However, by cleverly truncating the series (i.e., ignoring all except the first few terms of the series), Stokes obtained an accurate approximation to the integral that was far easier to evaluate than the integral itself. Stokes's research on asymptotic series led to fundamental insights about such series.

Fluorescence

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of

In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

of light, he described the phenomenon of fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, tha ...

, as exhibited by fluorspar and uranium glass, materials which he viewed as having the power to convert invisible ultra-violet radiation into radiation of longer wavelengths that are visible. The Stokes shift

__NOTOC__

Stokes shift is the difference (in energy, wavenumber or frequency units) between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra ( fluorescence and Raman being two examples) of the same electronic transition. I ...

, which describes this conversion, is named in Stokes's honour. A mechanical model, illustrating the dynamical principle of Stokes's explanation was shown. The offshoot of this, Stokes line

__NOTOC__

Stokes shift is the difference (in energy, wavenumber or frequency units) between positions of the band maxima of the absorption and emission spectra (fluorescence and Raman being two examples) of the same electronic transition. It i ...

, is the basis of Raman scattering

Raman scattering or the Raman effect () is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrational energy being gained by ...

. In 1883, during a lecture at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, Lord Kelvin said he had heard an account of it from Stokes many years before, and had repeatedly but vainly begged him to publish it.

Polarization

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarised light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarisation. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar, transparent

In the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and resolution of streams of polarised light from different sources, and in 1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarisation. About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862 he prepared for the British Association a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar, transparent calcite

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratc ...

crystals.

A paper on the long spectrum of the electric light bears the same date, and was followed by an inquiry into the absorption spectrum

Absorption spectroscopy refers to spectroscopic techniques that measure the absorption of radiation, as a function of frequency or wavelength, due to its interaction with a sample. The sample absorbs energy, i.e., photons, from the radiating ...

of blood.

Chemical analysis

The chemical identification oforganic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

bodies by their optical properties was treated in 1864; and later, in conjunction with the Rev. William Vernon Harcourt, he investigated the relation between the chemical composition and the optical properties of various glasses, with reference to the conditions of transparency and the improvement of achromatic telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

s. A still later paper connected with the construction of optical instruments discussed the theoretical limits to the aperture of microscope objectives.

Ophthalmology

In 1849, Stokes invented theStokes lens

Stokes lens also known as variable power cross cylinder lens is a lens used to diagnose a type of refractive error known as astigmatism.

Lens design

The Stokes lens also known as variable power cross cylinder lens, in its standard version, is a l ...

to detect astigmatism. It is a lens combination consisted of equal but opposite power cylindrical lenses attached together in such a way so that the lenses can be rotated relative to one another.

Other work

In other areas of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in

In other areas of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

s (1851) and his inquiries in connection with Crookes radiometer; his explanation of the light border frequently noticed in photographs just outside the outline of a dark body seen against the sky (1882); and, still later, his theory of the x-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s, which he suggested might be transverse waves travelling as innumerable solitary waves, not in regular trains. Two long papers published in 1849 – one on attractions and Clairaut's theorem

Clairaut's theorem characterizes the surface gravity on a viscous rotating ellipsoid in hydrostatic equilibrium under the action of its gravitational field and centrifugal force. It was published in 1743 by Alexis Claude Clairaut in a treatise ...

, and the other on the variation of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

at the surface of the Earth (1849) – Stokes' gravity formula—also demand notice, as do his mathematical memoirs on the critical values of sums of periodic series (1847) and on the numerical calculation of a class of definite integral

In mathematics, an integral assigns numbers to functions in a way that describes displacement, area, volume, and other concepts that arise by combining infinitesimal data. The process of finding integrals is called integration. Along with ...

s and infinite series (1850) and his discussion of a differential equation

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, ...

relating to the breaking of railway bridges (1849), research related to his evidence given to the ''Royal Commission on the Use of Iron in Railway structures'' after the Dee Bridge disaster of 1847.

Unpublished research

Many of Stokes' discoveries were not published, or were only touched upon in the course of his oral lectures. One such example is his work in the theory ofspectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

.

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at

In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions, theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time, and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

. These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of

These statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had failed to take one essential step in the argument—not perceiving that emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

.

In another way, too, Stokes did much for the progress of mathematical physics. Soon after he was elected to the Lucasian chair he announced that he regarded it as part of his professional duties to help any member of the university in difficulties he might encounter in his mathematical studies, and the assistance rendered was so real that pupils were glad to consult him, even after they had become colleagues, on mathematical and physical problems in which they found themselves at a loss. Then during the thirty years he acted as secretary of the Royal Society he exercised an enormous if inconspicuous influence on the advancement of mathematical and physical science, not only directly by his own investigations, but indirectly by suggesting problems for inquiry and inciting men to attack them, and by his readiness to give encouragement and help.

Contributions to engineering

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee Bridge disaster in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains.

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee Bridge disaster in May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of passing trains. Cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

is brittle in tension or bending, and many other similar bridges had to be demolished or reinforced.

Work on religion

Stokes generally held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, he became president of the

Stokes generally held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, he became president of the Victoria Institute

The Victoria Institute, or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, was founded in 1865, as a response to the publication of ''On the Origin of Species'' and ''Essays and Reviews''. Its stated objective was to defend "the great truths revealed in ...

, which had been founded to defend evangelical Christian principles against challenges from the new sciences, especially the Darwinian theory of biological evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. He gave the 1891 Gifford lecture on natural theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

. He was also the vice-president of the British and Foreign Bible Society

The British and Foreign Bible Society, often known in England and Wales as simply the Bible Society, is a non-denominational Christian Bible society with charity status whose purpose is to make the Bible available throughout the world.

The So ...

and was actively involved in doctrinal debates concerning missionary work. However, although his religious views were mostly orthodox, he was unusual among Victorian evangelicals in rejecting eternal punishment in hell, and instead was a proponent of Conditionalism.

As President of the Victoria Institute, Stokes wrote: ''"We all admit that the book of Nature and the book of Revelation come alike from God, and that consequently there can be no real discrepancy between the two if rightly interpreted. The provisions of Science and Revelation are, for the most part, so distinct that there is little chance of collision. But if an apparent discrepancy should arise, we have no right on principle, to exclude either in favour of the other. For however firmly convinced we may be of the truth of revelation, we must admit our liability to err as to the extent or interpretation of what is revealed; and however strong the scientific evidence in favour of a theory may be, we must remember that we are dealing with evidence which, in its nature, is probable only, and it is conceivable that wider scientific knowledge might lead us to alter our opinion".''

Personal life

He married, on 4 July 1857 at St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh, Mary Susanna Robinson, daughter of the astronomer Rev Thomas Romney Robinson. They had five children: Arthur Romney, who inherited the baronetcy; Susanna Elizabeth, who died in infancy; Isabella Lucy (Mrs Laurence Humphry) who contributed the personal memoir of her father in "Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of the Late George Gabriel Stokes, Bart"; Dr William George Gabriel, physician, a troubled man who committed suicide aged 30 while temporarily insane; and Dora Susanna, who died in infancy. His male line and hence his baronetcy has since become extinct.Legacy and honours

*

*Lucasian Professor of Mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of P ...

at Cambridge University

*From the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, of which he became a fellow in 1851, he received the Rumford Medal in 1852 in recognition of his inquiries into the wavelength of light, and later, in 1893, the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

.

*In 1869 he presided over the Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

meeting of the British Association.

*From 1883 to 1885 he was Burnett lecturer at Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), a ...

, his lectures on light, which were published in 1884–1887, dealing with its nature, its use as a means of investigation, and its beneficial effects.

*On 18 April 1888 he was admitted as a Freeman of the City of London.

*On 6 July 1889 Queen Victoria made him a Baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

as Sir George Gabriel Stokes of Lensfield Cottage in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom; the title became extinct in 1916.

*In 1891, as Gifford lecturer, he published a volume on Natural Theology.

*Member of the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n Order Pour le Mérite

*His academic distinctions included honorary degrees from many universities, including

**''Doctor mathematicae (honoris causa

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

)'' from the Royal Frederick University on 6 September 1902, when they celebrated the centennial of the birth of mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

Niels Henrik Abel.

*The stokes, a unit of kinematic viscosity, is named after him.

*In July 2017, Dublin City University

Dublin City University (abbreviated as DCU) ( ga, Ollscoil Chathair Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a university based on the Northside of Dublin, Ireland. Created as the '' National Institute for Higher Education, Dublin'' in 1975, it enrolled its ...

named a building after Stokes in recognition of his contributions to physics and mathematics.Raidió Teilifís Éireann, 5 July 2017

Publications

Stokes's mathematical and physical papers (see external links) were published in a collected form in five volumes; the first three (Cambridge, 1880, 1883, and 1901) under his own editorship, and the two last (Cambridge, 1904 and 1905) under that of SirJoseph Larmor

Sir Joseph Larmor (11 July 1857 – 19 May 1942) was an Irish and British physicist and mathematician who made breakthroughs in the understanding of electricity, dynamics, thermodynamics, and the electron theory of matter. His most influen ...

, who also selected and arranged the ''Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of Stokes'' published at Cambridge in 1907.

See also

* Stokes flowReferences

*Further reading

*Wilson, David B., ''Kelvin and Stokes A Comparative Study in Victorian Physics'', (1987) ** * *Peter R Lewis''Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879''

Tempus (2004). * *PR Lewis, ''Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847'', Tempus Publishing (2007) *

George Gabriel Stokes: Life, Science and Faith

' Edited by Mark McCartney, Andrew Whitaker, and Alastair Wood, Oxford University Press, 2019.

External links

* ** (1907), ed. by J. Larmor * Mathematical and physical paper

volume 1

an

volume 2

from the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

* Mathematical and physical papersvolumes 1 to 5

from the University of Michigan Digital Collection.

Life and work of Stokes

''Natural Theology''

(1891), Adam and Charles Black. (1891–93 Gifford Lectures) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stokes, George Gabriel 1819 births 1903 deaths People from County Sligo 19th-century Anglo-Irish people Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Fellows of Pembroke College, Cambridge Masters of Pembroke College, Cambridge Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom Irish mathematicians Irish physicists British physicists Optical physicists 19th-century British mathematicians Fluid dynamicists Irish Anglicans Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for the University of Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences UK MPs 1886–1892 Viscosity Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Senior Wranglers