Second industrial revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid

The

The  The next great advance in steel making was the

The next great advance in steel making was the

The increase in steel production from the 1860s meant that railways could finally be made from steel at a competitive cost. Being a much more durable material, steel steadily replaced iron as the standard for railway rail, and due to its greater strength, longer lengths of rails could now be rolled.

The increase in steel production from the 1860s meant that railways could finally be made from steel at a competitive cost. Being a much more durable material, steel steadily replaced iron as the standard for railway rail, and due to its greater strength, longer lengths of rails could now be rolled.

His In 1881,

In 1881,

in ''The Times'', 29 December 1881 Swan's lightbulb had already been used in 1879 to light Mosley Street, in

The use of

The use of

pp. 9–10.

/ref> During the 1840s through 1860s, this standard was often used in the United States and Canada as well, in addition to myriad intra- and inter-company standards. The importance of machine tools to mass production is shown by the fact that production of the Ford Model T used 32,000 machine tools, most of which were powered by electricity.

This era saw the birth of the modern ship as disparate technological advances came together.

The

This era saw the birth of the modern ship as disparate technological advances came together.

The

Dunlop, What sets Dunlop apart, History, 1889

/ref> Dunlop's development of the pneumatic tyre arrived at a crucial time in the development of road transport and commercial production began in late 1890.

German inventor

German inventor

The invention of Parson's steam turbine made cheap and plentiful electricity possible and revolutionized Turbinia, marine transport and naval warfare. By the time of Parson's death, his turbine had been adopted for all major world power stations. Unlike earlier steam engines, the turbine produced rotary power rather than reciprocating power which required a crank and heavy flywheel. The large number of stages of the turbine allowed for high efficiency and reduced size by 90%. The turbine's first application was in shipping followed by electric generation in 1903. The first widely used

The first commercial

The first commercial

Later in the Second Industrial Revolution,

Later in the Second Industrial Revolution,

excerpt and text search

* Beaudreau, Bernard C. ''The Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes: How the Second Industrial Revolution Passed Great Britain'' (2006) * * Broadberry, Stephen, and Kevin H. O'Rourke. ''The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe'' (2 vol. 2010), covers 1700 to present * Chandler, Jr., Alfred D. ''Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism'' (1990). * Chant, Colin, ed. ''Science, Technology and Everyday Life, 1870–1950'' (1989) emphasis on Britain * * Hull, James O. "From Rostow to Chandler to You: How revolutionary was the second industrial revolution?" ''Journal of European Economic History',' Spring 1996, Vol. 25 Issue 1, pp. 191–208 * Kornblith, Gary. ''The Industrial Revolution in America'' (1997) * * * Licht, Walter. ''Industrializing America: The Nineteenth Century'' (1995) * Mokyr, Joe

''The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870–1914''

(1998) * Mokyr, Joel. ''The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain 1700–1850'' (2010) * Rider, Christine, ed. ''Encyclopedia of the Age of the Industrial Revolution, 1700–1920'' (2 vol. 2007) * Roberts, Wayne. "Toronto Metal Workers and the Second Industrial Revolution, 1889–1914," ''Labour / Le Travail'', Autumn 1980, Vol. 6, pp 49–72 * Smil, Vaclav. ''Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867–1914 and Their Lasting Impact''

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery

Discovery is the act of detecting something new, or something previously unrecognized as meaningful. With reference to sciences and academic disciplines, discovery is the observation of new phenomena, new actions, or new events and providing ne ...

, standardization, mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch ...

and industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The First Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going fr ...

, which ended in the middle of the 19th century, was punctuated by a slowdown in important inventions before the Second Industrial Revolution in 1870. Though a number of its events can be traced to earlier innovations in manufacturing, such as the establishment of a machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All ...

industry, the development of methods for manufacturing interchangeable parts, as well as the invention of the Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation ...

to produce steel, the Second Industrial Revolution is generally dated between 1870 and 1914 (the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

).

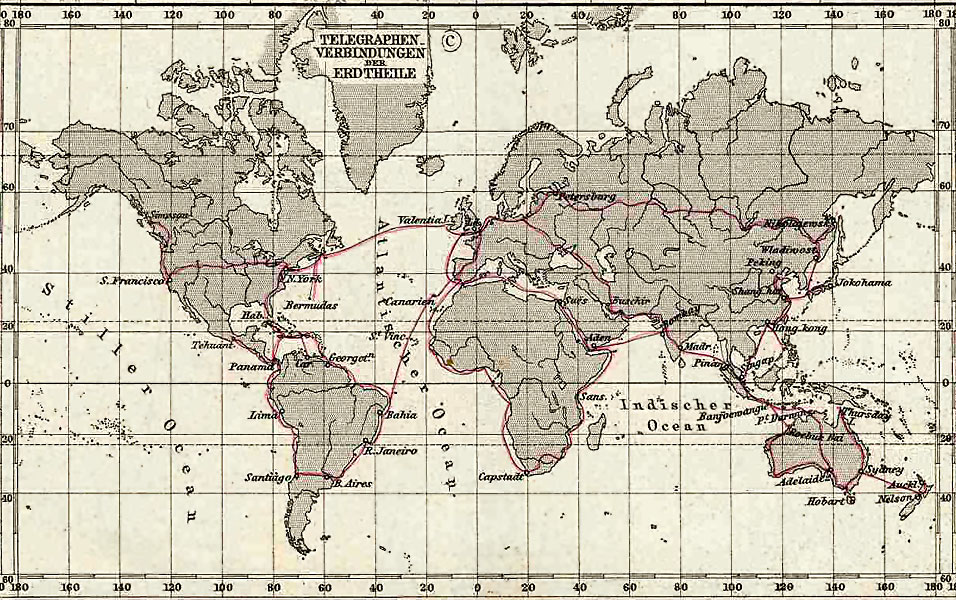

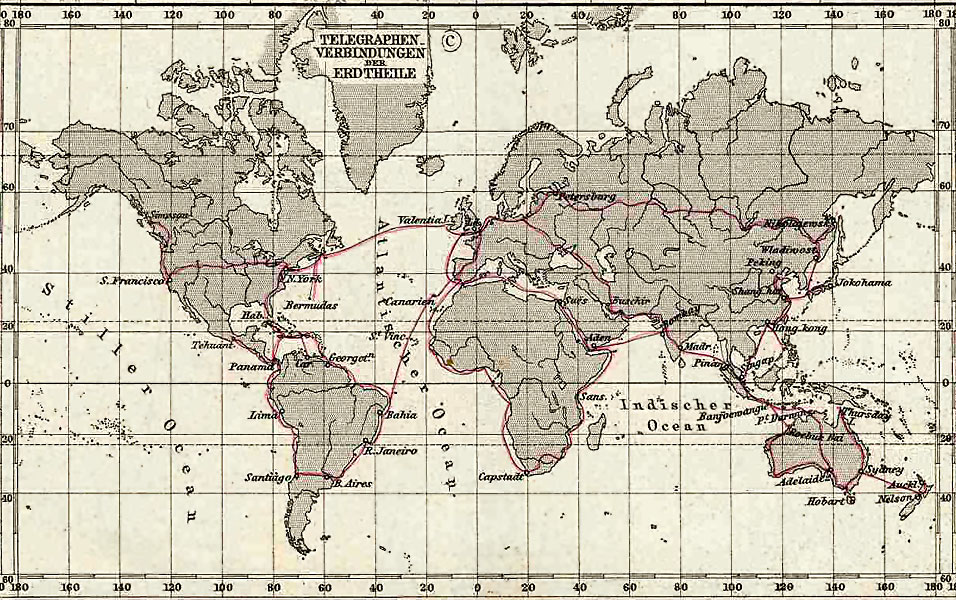

Advancements in manufacturing and production technology enabled the widespread adoption of technological systems such as telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

and railroad networks, gas and water supply

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavors or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes. Public water supply systems are crucial to properly functioning societies. Thes ...

, and sewage systems, which had earlier been concentrated to a few select cities. The enormous expansion of rail and telegraph lines after 1870 allowed unprecedented movement of people and ideas, which culminated in a new wave of globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

. In the same time period, new technological systems were introduced, most significantly electrical power

Electric power is the rate at which electrical energy is transferred by an electric circuit. The SI unit of power is the watt, one joule per second. Standard prefixes apply to watts as with other SI units: thousands, millions and billions o ...

and telephones. The Second Industrial Revolution continued into the 20th century with early factory electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

and the production line

A production line is a set of sequential operations established in a factory where components are assembled to make a finished article or where materials are put through a refining process to produce an end-product that is suitable for onward c ...

; it ended at the beginning of World War I.

The Second Industrial Revolution is followed by the Third Industrial Revolution starting in 1947.

Overview

The Second Industrial Revolution was a period of rapid industrial development, primarily in the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States, but also in France, theLow Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, Italy and Japan. It followed on from the First Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going fr ...

that began in Britain in the late 18th century that then spread throughout Western Europe. It came to an end with the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. While the First Revolution was driven by limited use of steam engines, interchangeable parts and mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch ...

, and was largely water-powered (especially in the United States), the Second was characterized by the build-out of railroads, large-scale iron and steel production, widespread use of machinery in manufacturing, greatly increased use of steam power, widespread use of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, use of petroleum and the beginning of electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

. It also was the period during which modern organizational methods for operating large scale businesses over vast areas came into use.

The concept was introduced by Patrick Geddes

Sir Patrick Geddes (2 October 1854 – 17 April 1932) was a British biologist, sociologist, Comtean positivist, geographer, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He is known for his innovative thinking in the fields of urban planning ...

, '' Cities in Evolution'' (1910), and was being used by economists such as Erich Zimmermann

Erich Walter Zimmermann, resource economist, was born in Mainz, Germany, on July 31, 1888 and died in Austin, United States of America, on February 16, 1961. He was an economist at the University of North Carolina and later the University of Texas ...

(1951), but David Landes

David Saul Landes (April 29, 1924 – August 17, 2013) was a professor of economics and of history at Harvard University. He is the author of ''Bankers and Pashas'', '' Revolution in Time'', '' The Unbound Prometheus'', '' The Wealth and Poverty ...

' use of the term in a 1966 essay and in ''The Unbound Prometheus

''The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present'' is an economic history book by David S. Landes. Its focus is on the Industrial Revolution in England and its spread to the rest ...

'' (1972) standardized scholarly definitions of the term, which was most intensely promoted by Alfred Chandler (1918–2007). However, some continue to express reservations about its use.

Landes (2003) stresses the importance of new technologies, especially, the internal combustion engine

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal combus ...

, petroleum, new materials and substances, including alloys and chemicals

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wit ...

, electricity and communication technologies (such as the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, telephone and radio).

One author has called the period from 1867–1914 during which most of the great innovations were developed "The Age of Synergy" since the inventions and innovations were engineering and science-based.

Industry and technology

A synergy between iron and steel, railroads and coal developed at the beginning of the Second Industrial Revolution. Railroads allowed cheap transportation of materials and products, which in turn led to cheap rails to build more roads. Railroads also benefited from cheap coal for their steam locomotives. This synergy led to the laying of 75,000 miles of track in the U.S. in the 1880s, the largest amount anywhere in world history.Iron

Thehot blast

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. As this considerably reduced the fuel consumed, hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. ...

technique, in which the hot flue gas

Flue gas is the gas exiting to the atmosphere via a flue, which is a pipe or channel for conveying exhaust gases from a fireplace, oven, furnace, boiler or steam generator. Quite often, the flue gas refers to the combustion exhaust gas produc ...

from a blast furnace is used to preheat combustion air blown into a blast furnace, was invented and patented by James Beaumont Neilson

James Beaumont Neilson (22 June 1792 – 18 January 1865) was a Scottish inventor whose hot-blast process greatly increased the efficiency of smelting iron.

Life

He was the son of the engineer Walter Neilson, a millwright and later engin ...

in 1828 at Wilsontown Ironworks in Scotland. Hot blast was the single most important advance in fuel efficiency of the blast furnace as it greatly reduced the fuel consumption for making pig iron, and was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Falling costs for producing wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

coincided with the emergence of the railway in the 1830s.

The early technique of hot blast used iron for the regenerative heating medium. Iron caused problems with expansion and contraction, which stressed the iron and caused failure. Edward Alfred Cowper

Edward Alfred Cowper (10 December 1819 London – 9 May 1893 Rastricke, Weybridge, Surrey) was a British mechanical engineer.

Biography

He was born on 10 December 1819 in London to professor Edward Shickle Cowper (1790–1852), head of the depa ...

developed the Cowper stove in 1857. This stove used firebrick as a storage medium, solving the expansion and cracking problem. The Cowper stove was also capable of producing high heat, which resulted in very high throughput of blast furnaces. The Cowper stove is still used in today's blast furnaces.

With the greatly reduced cost of producing pig iron with coke using hot blast, demand grew dramatically and so did the size of blast furnaces.

Steel

The

The Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation ...

, invented by Sir Henry Bessemer

Sir Henry Bessemer (19 January 1813 – 15 March 1898) was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one hundred years from 1856 to 1950. He ...

, allowed the mass-production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and bat ...

of steel, increasing the scale and speed of production of this vital material, and decreasing the labor requirements. The key principle was the removal of excess carbon and other impurities from pig iron by oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

with air blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten.

The "acid" Bessemer process had a serious limitation in that it required relatively scarce hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

ore which is low in phosphorus. Sidney Gilchrist Thomas

Sidney Gilchrist Thomas (16 April 1850 – 1 February 1885) was an English inventor, best known for his role in the iron and steel industry.

Life

Thomas was born at Canonbury, London, and was educated at Dulwich College. His father, a Welshman, w ...

developed a more sophisticated process to eliminate the phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

from iron. Collaborating with his cousin, Percy Gilchrist

Percy Carlyle Gilchrist FRS (27 December 1851 – 16 December 1935) was a British chemist and metallurgist.

Life

Gilchrist was born in Lyme Regis, Dorset, the son of Alexander and Anne Gilchrist and studied at Felsted and the Royal School of ...

a chemist at the Blaenavon Ironworks

Blaenavon Ironworks is a former industrial site which is now a museum in Blaenavon, Wales. The ironworks was of crucial importance in the development of the ability to use cheap, low quality, high sulphur iron ores worldwide. It was the site o ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, he patented his process in 1878; Bolckow Vaughan

Bolckow, Vaughan & Co., Ltd was an English steelmaking, ironmaking and mining company founded in 1864, based on the partnership since 1840 of its two founders, Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan (ironmaster), John Vaughan. The firm drove the dramat ...

& Co. in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

was the first company to use his patented process. His process was especially valuable on the continent of Europe, where the proportion of phosphoric iron was much greater than in England, and both in Belgium and in Germany the name of the inventor became more widely known than in his own country. In America, although non-phosphoric iron largely predominated, an immense interest was taken in the invention.

The next great advance in steel making was the

The next great advance in steel making was the Siemens–Martin process

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial Industrial furnace, furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to Steelmaking, produce steel. Because steel is difficult to ma ...

. Sir Charles William Siemens

Sir Carl Wilhelm Siemens (4 April 1823 – 19 November 1883), anglicised to Charles William Siemens, was a German-British electrical engineer and businessman.

Biography

Siemens was born in the village of Lenthe, today part of Gehrden, near Han ...

developed his regenerative furnace in the 1850s, for which he claimed in 1857 to able to recover enough heat to save 70–80% of the fuel. The furnace operated at a high temperature by using regenerative preheating of fuel and air for combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

. Through this method, an open-hearth furnace can reach temperatures high enough to melt steel, but Siemens did not initially use it in that manner.

French engineer Pierre-Émile Martin

Pierre-Émile Martin (; 18 August 1824, Bourges, Cher – 23 May 1915, Fourchambault) was a French industrial engineer. He applied the principle of recovery of the hot gas in an open hearth furnace, a process invented by Carl Wilhelm Siemens.

I ...

was the first to take out a license for the Siemens furnace and apply it to the production of steel in 1865. The Siemens–Martin process complemented rather than replaced the Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation ...

. Its main advantages were that it did not expose the steel to excessive nitrogen (which would cause the steel to become brittle), it was easier to control, and that it permitted the melting and refining of large amounts of scrap steel, lowering steel production costs and recycling an otherwise troublesome waste material. It became the leading steel making process by the early 20th century.

The availability of cheap steel allowed building larger bridges, railroads, skyscrapers, and ships. Other important steel products—also made using the open hearth process—were steel cable, steel rod and sheet steel which enabled large, high-pressure boilers and high-tensile strength steel for machinery which enabled much more powerful engines, gears and axles than were previously possible. With large amounts of steel it became possible to build much more powerful guns and carriages, tanks, armored fighting vehicles and naval ships.

Rail

The increase in steel production from the 1860s meant that railways could finally be made from steel at a competitive cost. Being a much more durable material, steel steadily replaced iron as the standard for railway rail, and due to its greater strength, longer lengths of rails could now be rolled.

The increase in steel production from the 1860s meant that railways could finally be made from steel at a competitive cost. Being a much more durable material, steel steadily replaced iron as the standard for railway rail, and due to its greater strength, longer lengths of rails could now be rolled. Wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

was soft and contained flaws caused by included dross

Dross is a mass of solid impurities floating on a molten metal or dispersed in the metal, such as in wrought iron. It forms on the surface of low- melting-point metals such as tin, lead, zinc or aluminium or alloys by oxidation of the metal. For ...

. Iron rails could also not support heavy locomotives and were damaged by hammer blow

In rail terminology, hammer blow or dynamic augment is a vertical force which alternately adds to and subtracts from the locomotive's weight on a wheel. It is transferred to the track by the driving wheels of many steam locomotives. It is an out-of ...

. The first to make durable rails

Rail or rails may refer to:

Rail transport

*Rail transport and related matters

*Rail (rail transport) or railway lines, the running surface of a railway

Arts and media Film

* ''Rails'' (film), a 1929 Italian film by Mario Camerini

* ''Rail'' ( ...

of steel rather than wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

was Robert Forester Mushet

Robert Forester Mushet (8 April 1811 – 29 January 1891) was a British metallurgist and businessman, born on 8 April 1811, in Coleford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. He was the youngest son of Scottish parents, Agnes Wilson ...

at the Darkhill Ironworks

Darkhill Ironworks, and the neighbouring Titanic Steelworks, are internationally important industrial remains associated with the development of the iron and steel industries. Both are scheduled monuments. They are located on the edge of a small ...

, Gloucestershire in 1857.

The first of Mushet's steel rails was sent to Derby Midland railway station

Derby railway station (, also known as Derby Midland) is a main line railway station serving the city of Derby in Derbyshire, England. Owned by Network Rail and managed by East Midlands Railway, the station is also used by CrossCountry services ...

. The rails were laid at part of the station approach where the iron rails had to be renewed at least every six months, and occasionally every three. Six years later, in 1863, the rail seemed as perfect as ever, although some 700 trains had passed over it daily. This provided the basis for the accelerated construction of railways throughout the world in the late nineteenth century.

The first commercially available steel rails in the US were manufactured in 1867 at the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Johnstown is a city in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 18,411 as of the 2020 census. Located east of Pittsburgh, Johnstown is the principal city of the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Metropolitan Statistical Area, whi ...

.

Steel rails lasted over ten times longer than did iron, and with the falling cost of steel, heavier weight rails were used. This allowed the use of more powerful locomotives, which could pull longer trains, and longer rail cars, all of which greatly increased the productivity of railroads. Rail became the dominant form of transport infrastructure throughout the industrialized world, producing a steady decrease in the cost of shipping seen for the rest of the century.

Electrification

The theoretical and practical basis for the harnessing of electric power was laid by the scientist and experimentalistMichael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

. Through his research on the magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

around a conductor carrying a direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or eve ...

, Faraday established the basis for the concept of the electromagnetic field in physics."Archives Biographies: Michael Faraday", The Institution of Engineering and Technology.His

invention

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an i ...

s of electromagnetic rotary devices were the foundation of the practical use of electricity in technology.

In 1881,

In 1881, Sir Joseph Swan

Sir Joseph Wilson Swan FRS (31 October 1828 – 27 May 1914) was an English physicist, chemist, and inventor. He is known as an independent early developer of a successful incandescent light bulb, and is the person responsible for develop ...

, inventor of the first feasible incandescent light bulb

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxid ...

, supplied about 1,200 Swan incandescent lamps to the Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy P ...

in the City of Westminster, London, which was the first theatre, and the first public building in the world, to be lit entirely by electricity.Description of lightbulb experimentin ''The Times'', 29 December 1881 Swan's lightbulb had already been used in 1879 to light Mosley Street, in

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, the first electrical street lighting installation in the world. This set the stage for the electrification of industry and the home. The first large scale central distribution supply plant was opened at Holborn Viaduct

Holborn Viaduct is a road bridge in London and the name of the street which crosses it (which forms part of the A40 route). It links Holborn, via Holborn Circus, with Newgate Street, in the City of London financial district, passing over ...

in London in 1882 and later at Pearl Street Station

Pearl Street Station was the first commercial central power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl Street in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City, just south of Fulton Street on a site measuring . The statio ...

in New York City.

The first modern power station in the world was built by the English electrical engineer Sebastian de Ferranti

Sebastian Pietro Innocenzo Adhemar Ziani de Ferranti (9 April 1864 – 13 January 1930) was a British electrical engineer and inventor.

Personal life

Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti was born in Liverpool, England. His Italian father, Cesare, was ...

at Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home to Deptford Dock ...

. Built on an unprecedented scale and pioneering the use of high voltage (10,000V) alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

, it generated 800 kilowatts and supplied central London. On its completion in 1891 it supplied high-voltage AC power that was then "stepped down" with transformers for consumer use on each street. Electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

allowed the final major developments in manufacturing methods of the Second Industrial Revolution, namely the assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

and mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch ...

.

Electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

was called "the most important engineering achievement of the 20th century" by the National Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Engineering is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy ...

. Electric lighting in factories greatly improved working conditions, eliminating the heat and pollution caused by gas lighting, and reducing the fire hazard to the extent that the cost of electricity for lighting was often offset by the reduction in fire insurance premiums. Frank J. Sprague

Frank Julian Sprague (July 25, 1857 in Milford, Connecticut – October 25, 1934) was an American inventor who contributed to the development of the electric motor, electric railways, and electric elevators. His contributions were especially ...

developed the first successful DC motor in 1886. By 1889 110 electric street railways were either using his equipment or in planning. The electric street railway became a major infrastructure before 1920. The AC motor ( Induction motor) was developed in the 1890s and soon began to be used in the electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

of industry. Household electrification did not become common until the 1920s, and then only in cities. Fluorescent light

A fluorescent lamp, or fluorescent tube, is a low-pressure mercury-vapor gas-discharge lamp that uses fluorescence to produce visible light. An electric current in the gas excites mercury vapor, which produces short-wave ultraviolet ligh ...

ing was commercially introduced at the 1939 World's Fair.

Electrification also allowed the inexpensive production of electro-chemicals, such as aluminium, chlorine, sodium hydroxide, and magnesium.

Machine tools

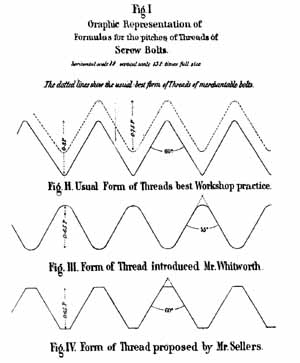

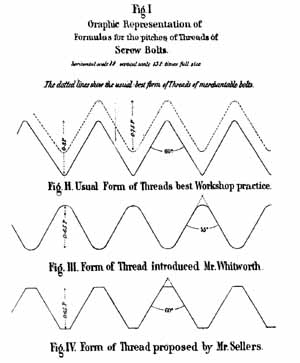

The use of

The use of machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All ...

s began with the onset of the First Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going fr ...

. The increase in mechanization

Mechanization is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text a machine is defined as follows:

In some fields, mechanization includes the ...

required more metal parts, which were usually made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

or wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

—and hand working lacked precision and was a slow and expensive process. One of the first machine tools was John Wilkinson's boring machine, that bored a precise hole in James Watt's first steam engine in 1774. Advances in the accuracy of machine tools can be traced to Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were ...

and refined by Joseph Whitworth

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet (21 December 1803 – 22 January 1887) was an English engineer, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for scre ...

. Standardization of screw threads began with Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were ...

around 1800, when the modern screw-cutting lathe

A screw-cutting lathe is a machine (specifically, a lathe) capable of cutting very accurate screw threads via single-point screw-cutting, which is the process of guiding the linear motion of the tool bit in a precisely known ratio to the rotatin ...

made interchangeable V-thread machine screws a practical commodity.

In 1841, Joseph Whitworth

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet (21 December 1803 – 22 January 1887) was an English engineer, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for scre ...

created a design that, through its adoption by many British railway companies, became the world's first national machine tool standard called British Standard Whitworth.pp. 9–10.

/ref> During the 1840s through 1860s, this standard was often used in the United States and Canada as well, in addition to myriad intra- and inter-company standards. The importance of machine tools to mass production is shown by the fact that production of the Ford Model T used 32,000 machine tools, most of which were powered by electricity.

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

is quoted as saying that mass production would not have been possible without electricity because it allowed placement of machine tools and other equipment in the order of the work flow.

Paper making

The first paper making machine was theFourdrinier machine

A paper machine (or paper-making machine) is an industrial machine which is used in the pulp and paper industry

to create paper in large quantities at high speed. Modern paper-making machines are based on the principles of the Fourdrinier Mach ...

, built by Sealy and Henry Fourdrinier

Henry Fourdrinier (11 February 1766 – 3 September 1854) was a British paper-making entrepreneur.

He was born in 1766, the son of paper maker and stationer Henry Fourdrinier, and grandson of the engraver Paul Fourdrinier, 1698–1758, sometimes ...

, stationers in London. In 1800, Matthias Koops

Matthias Koops (active 1789–1805) was a British paper-maker who invented the first practical processes for manufacturing paper from wood pulp, straw, or recycled waste paper, without the necessity of including expensive linen or cotton rags.

K ...

, working in London, investigated the idea of using wood to make paper, and began his printing business a year later. However, his enterprise was unsuccessful due to the prohibitive cost at the time.

It was in the 1840s, that Charles Fenerty

Charles Fenerty (January 1821 – 10 June 1892), was a Canadian inventor who invented the wood pulp process for papermaking, which was first adapted into the production of newsprint. Fenerty was also a poet (writing over 32 known poems).

Early ...

in Nova Scotia and Friedrich Gottlob Keller

Friedrich Gottlob Keller (born 27 June 1816 in Hainichen, Saxony; died 8 September 1895 in Krippen, Saxony) was a German machinist and inventor, who (at the same time as Charles Fenerty) invented the wood pulp process for use in papermaking. He i ...

in Saxony both invented a successful machine which extracted the fibres from wood (as with rags) and from it, made paper. This started a new era for paper making

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

, and, together with the invention of the fountain pen

A fountain pen is a writing instrument which uses a metal nib to apply a water-based ink to paper. It is distinguished from earlier dip pens by using an internal reservoir to hold ink, eliminating the need to repeatedly dip the pen in an in ...

and the mass-produced pencil

A pencil () is a writing or drawing implement with a solid pigment core in a protective casing that reduces the risk of core breakage, and keeps it from marking the user's hand.

Pencils create marks by physical abrasion, leaving a trail ...

of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th century economy and society in industrialized countries. With the introduction of cheaper paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became gradually available by 1900. Cheap wood based paper also allowed keeping personal diaries or writing letters and so, by 1850, the clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service ...

, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job. By the 1880s chemical processes for paper manufacture were in use, becoming dominant by 1900.

Petroleum

Thepetroleum industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry or the oil patch, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The larges ...

, both production and refining, began in 1848 with the first oil works in Scotland. The chemist James Young set up a tiny business refining the crude oil in 1848. Young found that by slow distillation he could obtain a number of useful liquids from it, one of which he named "paraffine oil" because at low temperatures it congealed into a substance resembling paraffin wax. In 1850 Young built the first truly commercial oil-works and oil refinery in the world at Bathgate

Bathgate ( sco, Bathket or , gd, Both Chèit) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland, west of Livingston, Scotland, Livingston and adjacent to the M8 motorway (Scotland), M8 motorway. Nearby towns are Armadale, West Lothian, Armadale, Blackburn, ...

, using oil extracted from locally mined torbanite

Torbanite, also known as boghead coal or channel coal, is a variety of fine-grained black oil shale. It usually occurs as lenticular masses, often associated with deposits of Permian coals.

Torbanite is classified as lacustrine type oil shale ...

, shale, and bituminous coal to manufacture naphtha

Naphtha ( or ) is a flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

Mixtures labelled ''naphtha'' have been produced from natural gas condensates, petroleum distillates, and the distillation of coal tar and peat. In different industries and regions ' ...

and lubricating oils; paraffin for fuel use and solid paraffin were not sold till 1856.

Cable tool drilling was developed in ancient China and was used for drilling brine wells. The salt domes also held natural gas, which some wells produced and which was used for evaporation of the brine. Chinese well drilling technology was introduced to Europe in 1828.

Although there were many efforts in the mid-19th century to drill for oil Edwin Drake

Edwin Laurentine Drake (March 29, 1819 – November 9, 1880), also known as Colonel Drake, was an American businessman and the first American to successfully drill for oil.

Early life

Edwin Drake was born in Greenville, New York on March 2 ...

's 1859 well near Titusville, Pennsylvania, is considered the first "modern oil well". Drake's well touched off a major boom in oil production in the United States. Drake learned of cable tool drilling from Chinese laborers in the U. S. The first primary product was kerosene for lamps and heaters. Similar developments around Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

fed the European market.

Kerosene lighting was much more efficient and less expensive than vegetable oils, tallow and whale oil. Although town gas lighting was available in some cities, kerosene produced a brighter light until the invention of the gas mantle

A Coleman white gas lantern mantle glowing at full brightness

An incandescent gas mantle, gas mantle or Welsbach mantle is a device for generating incandescent bright white light when heated by a flame. The name refers to its original heat sou ...

. Both were replaced by electricity for street lighting following the 1890s and for households during the 1920s. Gasoline was an unwanted byproduct of oil refining until automobiles were mass-produced after 1914, and gasoline shortages appeared during World War I. The invention of the Burton process The Burton process is a thermal cracking process invented by William Merriam Burton and Robert E. Humphreys, each of whom held a PhD in chemistry from Johns Hopkins University. The process they developed is often called the Burton process. More fa ...

for thermal cracking

In petrochemistry, petroleum geology and organic chemistry, cracking is the process whereby complex organic molecules such as kerogens or long-chain hydrocarbons are broken down into simpler molecules such as light hydrocarbons, by the breaking of ...

doubled the yield of gasoline, which helped alleviate the shortages.

Chemical

Synthetic dye

A dye is a colored substance that chemically bonds to the substrate to which it is being applied. This distinguishes dyes from pigments which do not chemically bind to the material they color. Dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution and ...

was discovered by English chemist William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in tryin ...

in 1856. At the time, chemistry was still in a quite primitive state; it was still a difficult proposition to determine the arrangement of the elements in compounds and chemical industry was still in its infancy. Perkin's accidental discovery was that aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starti ...

could be partly transformed into a crude mixture which when extracted with alcohol produced a substance with an intense purple colour. He scaled up production of the new "mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was one of the first synthetic dyes. It was discovered serendipitously by William Henry Perkin in 1856 while he was attempting to synthesise the phytochemical quinine for the treatment of ...

", and commercialized it as the world's first synthetic dye.

After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dye

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starting m ...

s appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe. Towards the end of the century, Perkin and other British companies found their research and development efforts increasingly eclipsed by the German chemical industry which became world dominant by 1914.

Maritime technology

This era saw the birth of the modern ship as disparate technological advances came together.

The

This era saw the birth of the modern ship as disparate technological advances came together.

The screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

was introduced in 1835 by Francis Pettit Smith

Sir Francis Pettit Smith (9 February 1808 – 12 February 1874) was an English inventor and, along with John Ericsson, one of the inventors of the screw propeller. He was also the driving force behind the construction of the world's first scr ...

who discovered a new way of building propellers by accident. Up to that time, propellers were literally screws, of considerable length. But during the testing of a boat propelled by one, the screw snapped off, leaving a fragment shaped much like a modern boat propeller. The boat moved faster with the broken propeller. The superiority of screw against paddles was taken up by navies. Trials with Smith's SS ''Archimedes'', the first steam driven screw, led to the famous tug-of-war competition in 1845 between the screw-driven and the paddle steamer ; the former pulling the latter backward at 2.5 knots (4.6 km/h).

The first seagoing iron steamboat was built by Horseley Ironworks

The Horseley Ironworks (sometimes spelled Horsley) was a major ironworks in the Tipton area in the county of Staffordshire, now the West Midlands, England.

History

Founded by Aaron Manby, it is most famous for constructing the first iron st ...

and named the ''Aaron Manby

''Aaron Manby'' was a landmark vessel in the science of shipbuilding as the first iron steamship to go to sea. She was built by Aaron Manby (1776–1850) at the Horseley Ironworks. She made the voyage to Paris in June 1822 under Captain (later ...

''. It also used an innovative oscillating engine for power. The boat was built at Tipton using temporary bolts, disassembled for transportation to London, and reassembled on the Thames in 1822, this time using permanent rivets.

Other technological developments followed, including the invention of the surface condenser

A surface condenser is a water-cooled shell and tube heat exchanger installed to condense exhaust steam from a steam turbine in thermal power stations. These condensers are heat exchangers which convert steam from its gaseous to its liquid stat ...

, which allowed boilers to run on purified water rather than salt water, eliminating the need to stop to clean them on long sea journeys. The '' Great Western''

,Beckett (2006), pp. 171–173 built by engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

, was the longest ship in the world at with a keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

and was the first to prove that transatlantic steamship services were viable. The ship was constructed mainly from wood, but Brunel added bolts and iron diagonal reinforcements to maintain the keel's strength. In addition to its steam-powered paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than abo ...

s, the ship carried four masts for sails.

Brunel followed this up with the ''Great Britain'', launched in 1843 and considered the first modern ship built of metal rather than wood, powered by an engine rather than wind or oars, and driven by propeller rather than paddle wheel. Brunel's vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, propeller-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry.

Highly efficient multiple expansion steam engines began being used on ships, allowing them to carry less coal than freight. The oscillating engine was first built by Aaron Manby

''Aaron Manby'' was a landmark vessel in the science of shipbuilding as the first iron steamship to go to sea. She was built by Aaron Manby (1776–1850) at the Horseley Ironworks. She made the voyage to Paris in June 1822 under Captain (later ...

and Joseph Maudslay in the 1820s as a type of direct-acting engine that was designed to achieve further reductions in engine size and weight. Oscillating engines had the piston rods connected directly to the crankshaft, dispensing with the need for connecting rods. To achieve this aim, the engine cylinders were not immobile as in most engines, but secured in the middle by trunnions which allowed the cylinders themselves to pivot back and forth as the crankshaft rotated, hence the term ''oscillating''.

It was John Penn, engineer for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

who perfected the oscillating engine. One of his earliest engines was the grasshopper beam engine

Grasshopper beam engines are beam engines that are pivoted at one end, rather than in the centre.

Usually the connecting rod to the crankshaft is placed ''between'' the piston and the beam's pivot. That is, they use a second-class lever, rather t ...

. In 1844 he replaced the engines of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

yacht, with oscillating engines of double the power, without increasing either the weight or space occupied, an achievement which broke the naval supply dominance of Boulton & Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Eng ...

and Maudslay, Son & Field. Penn also introduced the trunk engine

Trunk may refer to:

Biology

* Trunk (anatomy), synonym for torso

* Trunk (botany), a tree's central superstructure

* Trunk of corpus callosum, in neuroanatomy

* Elephant trunk, the proboscis of an elephant

Computing

* Trunk (software), in re ...

for driving screw propellers in vessels of war. (1846) and (1848) were the first ships to be fitted with such engines and such was their efficacy that by the time of Penn's death in 1878, the engines had been fitted in 230 ships and were the first mass-produced, high-pressure and high-revolution marine engines.

The revolution in naval design led to the first modern battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s in the 1870s, evolved from the ironclad design of the 1860s. The ''Devastation''-class turret ship

Turret ships were a 19th-century type of warship, the earliest to have their guns mounted in a revolving gun turret, instead of a broadside arrangement.

Background

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th century, ...

s were built for the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

as the first class of ocean-going capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

that did not carry sails, and the first whose entire main armament was mounted on top of the hull rather than inside it.

Rubber

Thevulcanization

Vulcanization (British: Vulcanisation) is a range of processes for hardening rubbers. The term originally referred exclusively to the treatment of natural rubber with sulfur, which remains the most common practice. It has also grown to includ ...

of rubber, by American Charles Goodyear

Charles Goodyear (December 29, 1800 – July 1, 1860) was an American self-taught chemist and manufacturing engineer who developed vulcanized rubber, for which he received patent number 3633 from the United States Patent Office on June 15, 1844. ...

and Englishman Thomas Hancock in the 1840s paved the way for a growing rubber industry, especially the manufacture of rubber tyre

A tire (American English) or tyre (British English) is a ring-shaped component that surrounds a wheel's rim to transfer a vehicle's load from the axle through the wheel to the ground and to provide traction on the surface over which ...

s

John Boyd Dunlop

John Boyd Dunlop (5 February 1840 – 23 October 1921) was a Scottish-born inventor and veterinary surgeon who spent most of his career in Ireland. Familiar with making rubber devices, he invented the first practical pneumatic tyres for his c ...

developed the first practical pneumatic tyre in 1887 in South Belfast. Willie Hume

William Hume (3 April 1862 – 1941The Bicycle, 12 Nov 1941, p6) was an Irish cyclist. He demonstrated the supremacy of John Boyd Dunlop's newly invented pneumatic tyres in 1889, winning the tyre's first ever races in Ireland and then Englan ...

demonstrated the supremacy of Dunlop's newly invented pneumatic tyres in 1889, winning the tyre's first ever races in Ireland and then England.The Golden Book of Cycling – William Hume, 1938. Archive maintained by 'The Pedal Club'.Dunlop, What sets Dunlop apart, History, 1889

/ref> Dunlop's development of the pneumatic tyre arrived at a crucial time in the development of road transport and commercial production began in late 1890.

Bicycles

The modern bicycle was designed by the English engineerHarry John Lawson

Henry John Lawson, also known as Harry Lawson, (23 February 1852–12 July 1925) was a British bicycle designer, racing cyclist, motor industry pioneer, and fraudster. As part of his attempt to create and control a British motor industry Lawson ...

in 1876, although it was John Kemp Starley

John Kemp Starley (24 December 1855 – 29 October 1901) was an English inventor and industrialist who is widely considered the inventor of the modern bicycle, and also originator of the name Rover.

Early life

Born on 24 December 1855 Star ...

who produced the first commercially successful safety bicycle a few years later. Its popularity soon grew, causing the bike boom

The bike boom or bicycle craze is any of several specific historic periods marked by increased bicycle enthusiasm, popularity, and sales.

Prominent examples include 1819 and 1868, as well as the decades of the 1890s and 1970sthe latter espec ...

of the 1890s.

Road networks improved greatly in the period, using the Macadam method pioneered by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam

John Loudon McAdam (23 September 1756 – 26 November 1836) was a Scottish civil engineer and road-builder. He invented a new process, " macadamisation", for building roads with a smooth hard surface, using controlled materials of ...

, and hard surfaced roads were built around the time of the bicycle craze of the 1890s. Modern tarmac Tarmac may refer to:

Engineered surfaces

* Tarmacadam, a mainly historical tar-based material for macadamising road surfaces, patented in 1902

* Asphalt concrete, a macadamising material using asphalt instead of tar which has largely superseded ta ...

was patented by British civil engineer Edgar Purnell Hooley

Edgar Purnell Hooley (5 June 1860 – 26 January 1942) was a Welsh inventor. After inventing Tarmacadam, tarmac in 1902, he founded Tarmac Group, Tar Macadam Syndicate Ltd the following year and registered tarmac as a trademark. Following a merger ...

in 1901..

Automobile

German inventor

German inventor Karl Benz

Carl Friedrich Benz (; 25 November 1844 – 4 April 1929), sometimes also Karl Friedrich Benz, was a German engine designer and automotive engineer. His Benz Patent Motorcar from 1885 is considered the first practical modern automobile and fir ...

patented the world's first automobile in 1886. It featured wire wheels (unlike carriages' wooden ones) with a four-stroke engine of his own design between the rear wheels, with a very advanced coil ignition G.N. Georgano and evaporative cooling rather than a radiator. Power was transmitted by means of two roller chain

Roller chain or bush roller chain is the type of chain drive most commonly used for transmission of mechanical power on many kinds of domestic, industrial and agricultural machinery, including conveyors, wire- and tube-drawing machines, pri ...

s to the rear axle. It was the first automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarde ...

entirely designed as such to generate its own power, not simply a motorized-stage coach or horse carriage.

Benz began to sell the vehicle (advertising it as the Benz Patent Motorwagen) in the late summer of 1888, making it the first commercially available automobile in history.

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

built his first car in 1896 and worked as a pioneer in the industry, with others who would eventually form their own companies, until the founding of Ford Motor Company in 1903. Ford and others at the company struggled with ways to scale up production in keeping with Henry Ford's vision of a car designed and manufactured on a scale so as to be affordable by the average worker. The solution that Ford Motor developed was a completely redesigned factory with machine tools and special purpose machines that were systematically positioned in the work sequence. All unnecessary human motions were eliminated by placing all work and tools within easy reach, and where practical on conveyors, forming the assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

, the complete process being called mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch ...

. This was the first time in history when a large, complex product consisting of 5000 parts had been produced on a scale of hundreds of thousands per year. The savings from mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batch ...

methods allowed the price of the Model T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relati ...

to decline from $780 in 1910 to $360 in 1916. In 1924 2 million T-Fords were produced and retailed $290 each.

Applied science

Applied science

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge obtained via conclusions from the method to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted ...

opened many opportunities. By the middle of the 19th century there was a scientific understanding of chemistry and a fundamental understanding of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of the ...

and by the last quarter of the century both of these sciences were near their present-day basic form. Thermodynamic principles were used in the development of physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistica ...

. Understanding chemistry greatly aided the development of basic inorganic chemical manufacturing and the aniline dye industries.

The science of metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

was advanced through the work of Henry Clifton Sorby

Henry Clifton Sorby (10 May 1826 – 9 March 1908) was an English microscopist and geologist. His major contribution was the development of techniques for studying iron and steel with microscopes. This paved the way for the mass production of st ...

and others. Sorby pioneered the study of iron and steel under microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

, which paved the way for a scientific understanding of metal and the mass-production of steel. In 1863 he used etching with acid to study the microscopic structure of metals and was the first to understand that a small but precise quantity of carbon gave steel its strength. This paved the way for Henry Bessemer

Sir Henry Bessemer (19 January 1813 – 15 March 1898) was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one hundred years from 1856 to 1950. H ...

and Robert Forester Mushet

Robert Forester Mushet (8 April 1811 – 29 January 1891) was a British metallurgist and businessman, born on 8 April 1811, in Coleford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. He was the youngest son of Scottish parents, Agnes Wilson ...

to develop the method for mass-producing steel.

Other processes were developed for purifying various elements such as chromium, molybdenum, titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

, vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pas ...

and nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

which could be used for making alloys with special properties, especially with steel. Vanadium steel

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( passi ...

, for example, is strong and fatigue resistant, and was used in half the automotive steel. Alloy steels were used for ball bearings which were used in large scale bicycle production in the 1880s. Ball and roller bearings also began being used in machinery. Other important alloys are used in high temperatures, such as steam turbine blades, and stainless steels for corrosion resistance.

The work of Justus von Liebig and August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann (8 April 18185 May 1892) was a German chemist who made considerable contributions to organic chemistry. His research on aniline helped lay the basis of the aniline-dye industry, and his research on coal tar laid the g ...

laid the groundwork for modern industrial chemistry. Liebig is considered the "father of the fertilizer industry" for his discovery of nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

as an essential plant nutrient and went on to establish Liebig's Extract of Meat Company

Liebig's Extract of Meat Company, established in the United Kingdom, was the producer of LEMCO brand Liebig's Extract of Meat and the originator of Oxo meat extracts and Oxo beef stock cubes. It was named after Baron Justus von Liebig, the 1 ...

which produced the Oxo meat extract

Meat extract is highly concentrated meat stock, usually made from beef or chicken. It is used to add meat flavour in cooking, and to make broth for soups and other liquid-based foods.

Meat extract was invented by Baron Justus von Liebig, a Germ ...

. Hofmann headed a school of practical chemistry in London, under the style of the Royal College of Chemistry

The Royal College of Chemistry: the laboratories. Lithograph

The Royal College of Chemistry (RCC) was a college originally based on Oxford Street in central London, England. It operated between 1845 and 1872.

The original building was designed ...

, introduced modern conventions for molecular modeling

Molecular modelling encompasses all methods, theoretical and computational, used to model or mimic the behaviour of molecules. The methods are used in the fields of computational chemistry, drug design, computational biology and materials scien ...

and taught Perkin who discovered the first synthetic dye.

The science of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of the ...

was developed into its modern form by Sadi Carnot, William Rankine

William John Macquorn Rankine (; 5 July 1820 – 24 December 1872) was a Scottish mechanical engineer who also contributed to civil engineering, physics and mathematics. He was a founding contributor, with Rudolf Clausius and William Thomson ( ...

, Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (; 2 January 1822 – 24 August 1888) was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founding fathers of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle ...

, William Thomson, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

, Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics, and the statistical explanation of the second law of ther ...

and J. Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in t ...

. These scientific principles were applied to a variety of industrial concerns, including improving the efficiency of boilers and steam turbines. The work of Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

and others was pivotal in laying the foundations of the modern scientific understanding of electricity.

Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

was particularly influential—his discoveries ushered in the era of modern physics. His most prominent achievement was to formulate a set of equations that described electricity, magnetism, and optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...