Romanticism in Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Romanticism in Scotland was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that developed between the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. It was part of the wider European Romantic movement, which was partly a reaction against the

Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the

Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the  Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Theatres had been discouraged by the

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Theatres had been discouraged by the

The Ossian cycle itself became a common subject for Scottish artists, and works based on its themes were created by figures such as Alexander Runciman (1736–85) and David Allan (1744–96).I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, fourth edn., 2009), , p. 554.''The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography'' (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), , pp. 34–5. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes in general, from viewing them as hostile, empty regions occupied by backward and marginal people, to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature, occupied by rugged primitives, who were now depicted in a dramatic fashion.C. W. J. Withers, ''Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), , pp. 151–3. Produced before his departure to Italy,

The Ossian cycle itself became a common subject for Scottish artists, and works based on its themes were created by figures such as Alexander Runciman (1736–85) and David Allan (1744–96).I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, fourth edn., 2009), , p. 554.''The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography'' (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), , pp. 34–5. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes in general, from viewing them as hostile, empty regions occupied by backward and marginal people, to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature, occupied by rugged primitives, who were now depicted in a dramatic fashion.C. W. J. Withers, ''Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), , pp. 151–3. Produced before his departure to Italy,

Important for the re-adoption of the Scots Baronial in the early nineteenth century was Abbotsford House, the residence of Scott. Re-built for him from 1816, it became a model for the revival of the style. Common features borrowed from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century houses included battlemented gateways,

Important for the re-adoption of the Scots Baronial in the early nineteenth century was Abbotsford House, the residence of Scott. Re-built for him from 1816, it became a model for the revival of the style. Common features borrowed from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century houses included battlemented gateways,

Perhaps the most influential composer of the first half of the nineteenth century was the German

Perhaps the most influential composer of the first half of the nineteenth century was the German

"William Wallace"

''Allmusic'', retrieved 11 May 2011. Drysdale's work often dealt with Scottish themes, including the overture ''Tam O’ Shanter'' (1890), the cantata ''The Kelpie'' (1891), the tone poem ''A Border Romance'' (1904), and the cantata ''Tamlane'' (1905). MacCunn's overture ''

In contrast to Enlightenment histories, which have been seen as attempting to draw general lessons about humanity from history, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder in his ''Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind'' (1784), set out the concept of ''

In contrast to Enlightenment histories, which have been seen as attempting to draw general lessons about humanity from history, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder in his ''Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind'' (1784), set out the concept of '' Among the most significant intellectual figures associated with Romanticism was

Among the most significant intellectual figures associated with Romanticism was

In the aftermath of the Jacobite risings, a movement to restore Stuart King

In the aftermath of the Jacobite risings, a movement to restore Stuart King

''The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland''

(GRIN Verlag, 2007), , pp. 22–5. The international craze for tartan, and for idealising a romanticised Highlands, was set off by the Ossian cycle and further popularised by the works of Scott. His "staging" of the royal

The dominant school of philosophy in Scotland in the late eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century is known as Common Sense Realism. It argued that there are certain concepts, such as our existence, the existence of solid objects and some basic moral "first principles", that are intrinsic to our make-up and from which all subsequent arguments and systems of morality must be derived. It can be seen as an attempt to reconcile the new scientific developments of the Enlightenment with religious belief.Paul C. Gutjahr, ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , p. 39. The origins of these arguments are in a reaction to the scepticism that became dominant in the Enlightenment, particularly that articulated by Scottish philosopher

The dominant school of philosophy in Scotland in the late eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century is known as Common Sense Realism. It argued that there are certain concepts, such as our existence, the existence of solid objects and some basic moral "first principles", that are intrinsic to our make-up and from which all subsequent arguments and systems of morality must be derived. It can be seen as an attempt to reconcile the new scientific developments of the Enlightenment with religious belief.Paul C. Gutjahr, ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , p. 39. The origins of these arguments are in a reaction to the scepticism that became dominant in the Enlightenment, particularly that articulated by Scottish philosopher

In literature, Romanticism is often thought to have ended in the 1830s, with a few commentators, like

In literature, Romanticism is often thought to have ended in the 1830s, with a few commentators, like

Scotland can make a claim to have begun the Romantic movement with writers such as Macpherson and Burns. In Scott it produced a figure of international fame and influence, whose virtual invention of the historical novel would be picked up by writers across the world, including

Scotland can make a claim to have begun the Romantic movement with writers such as Macpherson and Burns. In Scott it produced a figure of international fame and influence, whose virtual invention of the historical novel would be picked up by writers across the world, including

''An Encyclopedia of New Zealand'', retrieved 9 January 2008. In music, the early efforts of men like Burns, Scott and Thompson helped insert Scottish music into European, particularly German, classical music, and the later contributions of composers like MacCuun were part of a Scottish contribution to the British revival of interest in classical music in the late nineteenth century. The idea of history as a force and the romantic concept of revolution were highly influential on transcendentalists like Emerson, and through them on American literature in general. Romantic science maintained the prominence and reputation that Scotland had begun to obtain in the Enlightenment and helped in the development of many emerging fields of investigation, including geology and biology. According to Robert D. Purington, "to some the nineteenth century seems to be the century of Scottish science". Politically the initial function of Romanticism as pursued by Scott and others helped to diffuse some of the tension created by Scotland's place in the Union, but it also helped to ensure the survival of a common and distinct Scottish national identity that would play a major part in Scottish life and emerge as a significant factor in Scottish politics from the second half of the twentieth century. Externally, modern images of Scotland worldwide, its landscape, culture, sciences and arts, are still largely defined by those created and popularised by Romanticism.G. Jack and A. M. Phipps, ''Tourism And Intercultural Exchange: Why Tourism Matters'' (Channel View Publications, 2005), , p. 147.

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, emphasising individual, national and emotional responses, moving beyond Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

and Classicist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Cla ...

models, particularly to the Middle Ages. The concept of a separate national Scottish Romanticism was first articulated by the critics Ian Duncan and Murray Pittock in the Scottish Romanticism in World Literatures Conference held at UC Berkeley in 2006 and in the latter's ''Scottish and Irish Romanticism'' (2008), which argued for a national Romanticism based on the concepts of a distinct national public sphere and differentiated inflection of literary genres; the use of Scots language; the creation of a heroic national history through an Ossianic or Scottian 'taxonomy of glory' and the performance of a distinct national self in diaspora.

In the arts, Romanticism manifested itself in literature and drama in the adoption of the mythical bard Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined unde ...

, the exploration of national poetry in the work of Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

and in the historical novels of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

. Scott also had a major impact on the development of a national Scottish drama. Art was heavily influenced by Ossian and a new view of the Highlands as the location of a wild and dramatic landscape. Scott profoundly affected architecture through his re-building of Abbotsford House in the early nineteenth century, which set off the boom in the Scots Baronial revival. In music, Burns was part of an attempt to produce a canon of Scottish song, which resulted in a cross fertilisation of Scottish and continental classical music, with romantic music becoming dominant in Scotland into the twentieth century.

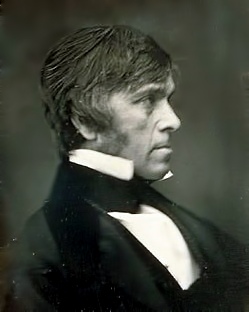

Intellectually, Scott and figures like Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

played a part in the development of historiography and the idea of the historical imagination. Romanticism also influenced science, particularly the life sciences, geology, optics and astronomy, giving Scotland a prominence in these areas that continued into the late nineteenth century. Scottish philosophy

Scottish philosophy is a philosophical tradition created by philosophers belonging to Scottish universities. Although many philosophers such as Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, Thomas Reid, and Adam Smith are familiar to almost all philosophers ...

was dominated by Scottish Common Sense Realism, which shared some characteristics with Romanticism and was a major influence on the development of Transcendentalism. Scott also played a major part in defining Scottish and British politics, helping to create a romanticised view of Scotland and the Highlands that fundamentally changed Scottish national identity.

Romanticism began to subside as a movement in the 1830s, but it continued to significantly affect areas such as music until the early twentieth century. It also had a lasting impact on the nature of Scottish identity and outside perceptions of Scotland.

Definitions

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

was a complex artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the eighteenth century in western Europe, and gained strength during and after the Industrial and French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

s.A. Chandler, ''A Dream of Order: the Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature'' (London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), p. 4. It was partly a revolt against the political norms of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

which rationalised nature, and was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but significantly influenced historiography, philosophy and the natural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeat ...

. However in Scotland it has been argued that Romanticism displayed a degree of continuity with some of the key themes of Enlightenment thought.

Romanticism has been seen as "the revival of the life and thought of the Middle Ages", reaching beyond Rationalist and Classicist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Cla ...

models to elevate medievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval, in an attempt to escape the confines of population growth, urban sprawl and industrialism, embracing the exotic, unfamiliar and distant. It is also associated with political revolutions, beginning with those in Americana and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and movements for independence, particularly in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. It is often thought to incorporate an emotional assertion of the self and of individual experience along with a sense of the infinite, transcendental and sublime. In art there was a stress on imagination, landscape and a spiritual correspondence with nature. It has been described by Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and '' Je ...

as "an unending revolt against classical form, conservative morality, authoritarian government, personal insincerity, and human moderation".

Literature and drama

Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the

Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza The Burns stanza is a verse form named after the Scottish poet Robert Burns, who used it in some fifty poems. It was not, however, invented by Burns, and prior to his use of it was known as the standard Habbie, after the piper Habbie Simpson (155 ...

as a poetic form. James Macpherson

James Macpherson (Gaelic: ''Seumas MacMhuirich'' or ''Seumas Mac a' Phearsain''; 27 October 1736 – 17 February 1796) was a Scottish writer, poet, literary collector and politician, known as the "translator" of the Ossian cycle of epic poem ...

(1736–96) was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation. Claiming to have found poetry written by the ancient bard Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora'' (1763), and later combined unde ...

, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics. ''Fingal'', written in 1762, was speedily translated into many European languages, and its appreciation of natural beauty and treatment of the ancient legend has been credited more than any single work with bringing about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German literature, through its influence on Johann Gottfried von Herder and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

. It was also popularised in France by figures that included Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

. Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from the Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.

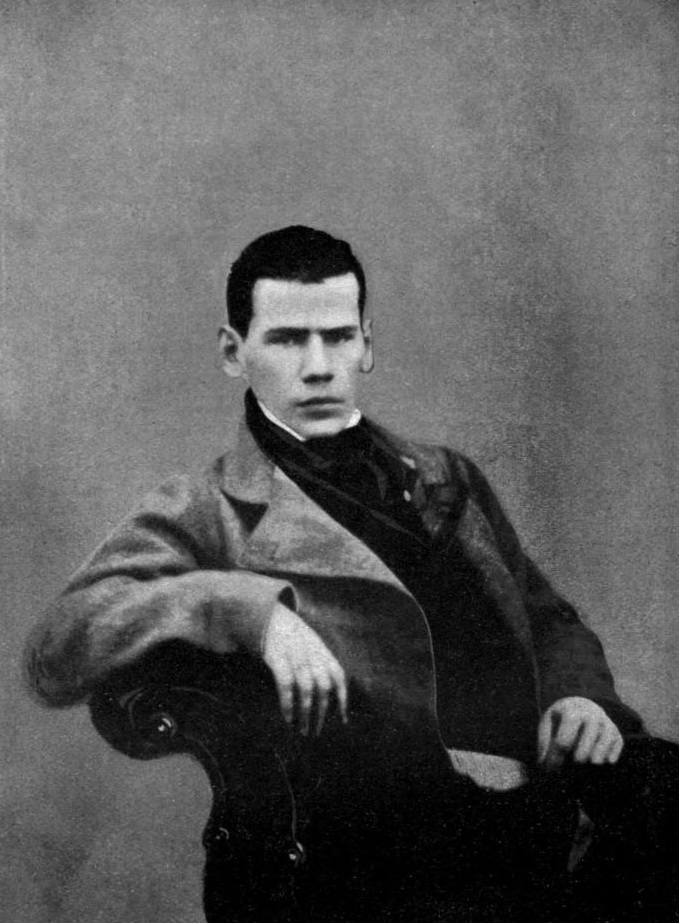

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

(1759–96) and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

(1771–1832) were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbo ...

of Scotland and a major influence on the Romantic movement. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne

"Auld Lang Syne" (: note "s" rather than "z") is a popular song, particularly in the English-speaking world. Traditionally, it is sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on New Year's Eve. By extension, it is also often ...

" is often sung at Hogmanay

Hogmanay ( , ) is the Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day (1 January) or i ...

(the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae

"Scots Wha Hae" (English: ''Scots Who Have''; gd, Brosnachadh Bhruis) is a patriotic song of Scotland written using both words of the Scots language and English, which served for centuries as an unofficial national anthem of the country, but h ...

" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and Europea ...

of the country. Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, '' Waverley'' in 1814, is often called the first historical novel. It launched a highly successful career, with other historical novels such as '' Rob Roy'' (1817), '' The Heart of Midlothian'' (1818) and ''Ivanhoe

''Ivanhoe: A Romance'' () by Walter Scott is a historical novel published in three volumes, in 1819, as one of the Waverley novels. Set in England in the Middle Ages, this novel marked a shift away from Scott’s prior practice of setting ...

'' (1820). Scott probably did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century. Other major literary figures connected with Romanticism include the poets and novelists James Hogg

James Hogg (1770 – 21 November 1835) was a Scottish poet, novelist and essayist who wrote in both Scots and English. As a young man he worked as a shepherd and farmhand, and was largely self-educated through reading. He was a friend of many ...

(1770–1835), Allan Cunningham (1784–1842) and John Galt

John Galt () is a character in Ayn Rand's novel ''Atlas Shrugged'' (1957). Although he is not identified by name until the last third of the novel, he is the object of its often-repeated question "Who is John Galt?" and of the quest to discover ...

(1779–1839).

Scotland was also the location of two of the most important literary magazines of the era, ''The Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' (founded in 1802) and '' Blackwood's Magazine'' (founded in 1817), which significantly influenced the development of British literature and drama in the era of Romanticism. Ian Duncan and Alex Benchimol suggest that publications like the novels of Scott and these magazines were part of a highly dynamic Scottish Romanticism that by the early nineteenth century, caused Edinburgh to emerge as the cultural capital of Britain and become central to a wider formation of a "British Isles nationalism."

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Theatres had been discouraged by the

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. Theatres had been discouraged by the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

and fears of Jacobite assemblies. In the later eighteenth century, many plays were written for and performed by small amateur companies and were not published and so most have been lost. Towards the end of the century there were " closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Scott, Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

Romanticism.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 229–30.

The Scottish national drama that emerged in the early nineteenth century was largely historical in nature and based around a core of adaptations of Scott's Waverley novels. The existing repertoire of Scottish-themed plays included Shakespeare's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' (c. 1605), Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friendsh ...

's '' Maria Stuart'' (1800), John Home

Rev John Home FRSE (13 September 1722 – 4 September 1808) was a Scottish minister, soldier and author. His play ''Douglas'' was a standard Scottish school text until the Second World War, but his work is now largely neglected. In 1783 he w ...

's ''Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

* Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil ...

'' (1756) and Ramsay's '' The Gentle Shepherd'' (1725), with the last two being the most popular plays among amateur groups. Ballets with Scottish themes included ''Jockey and Jenny'' and ''Love in the Highlands''.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , p. 231. Scott was keenly interested in drama, becoming a shareholder in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh

The history of the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh involves two sites. The first building, on Princes Street, opened 1769 and was rebuilt in 1830 by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. The second site was on Broughton Street.

History

The first Theatre Royal wa ...

. Baillie's Highland themed ''Family Legend'' was first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama. Scott also wrote five plays, of which ''Hallidon Hill'' (1822) and ''MacDuff's Cross'' (1822) were patriotic Scottish histories.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 185–6. Adaptations of the Waverley novels, first performed primarily in minor theatres, rather than the larger Patent theatre

The patent theatres were the theatres that were licensed to perform "spoken drama" after the Restoration of Charles II as King of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1660. Other theatres were prohibited from performing such "serious" drama, but ...

s, included ''The Lady in the Lake'' (1817), '' The Heart of Midlothian'' (1819) (specifically described as a "romantic play" for its first performance), and ''Rob Roy'', which underwent over 1,000 performances in Scotland in this period. Also adapted for the stage were '' Guy Mannering'', '' The Bride of Lammermoor'' and '' The Abbot''. These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.

Art

The Ossian cycle itself became a common subject for Scottish artists, and works based on its themes were created by figures such as Alexander Runciman (1736–85) and David Allan (1744–96).I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, fourth edn., 2009), , p. 554.''The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography'' (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), , pp. 34–5. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes in general, from viewing them as hostile, empty regions occupied by backward and marginal people, to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature, occupied by rugged primitives, who were now depicted in a dramatic fashion.C. W. J. Withers, ''Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), , pp. 151–3. Produced before his departure to Italy,

The Ossian cycle itself became a common subject for Scottish artists, and works based on its themes were created by figures such as Alexander Runciman (1736–85) and David Allan (1744–96).I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, fourth edn., 2009), , p. 554.''The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography'' (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), , pp. 34–5. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes in general, from viewing them as hostile, empty regions occupied by backward and marginal people, to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature, occupied by rugged primitives, who were now depicted in a dramatic fashion.C. W. J. Withers, ''Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), , pp. 151–3. Produced before his departure to Italy, Jacob More

Jacob More (1740–1793) was a Scottish landscape painter.

Biography

Jacob More was born in 1740 in Edinburgh. He studied landscape and decorative painting with James Norie's firm. He took the paintings of Gaspard Dughet and Claude Lorrain as ...

's (1740–93) series of four paintings "Falls of Clyde" (1771–73) have been described by art historian Duncan Macmillan as treating the waterfalls as "a kind of natural national monument" and has been seen as an early work in developing a romantic sensibility to the Scottish landscape. Runciman was probably the first artist to paint Scottish landscapes in watercolours in the more romantic style that was emerging towards the end of the eighteenth century.

The effect of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century artists such as Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840) and John Knox (1778–1845). Raeburn was the most significant artist of the period to pursue his entire career in Scotland. He was born in Edinburgh and returned there after a trip to Italy in 1786. He is most famous for his intimate portraits of leading figures in Scottish life, going beyond the aristocracy to lawyers, doctors, professors, writers and ministers, adding elements of Romanticism to the tradition of Reynolds. He became a knight in 1822 and the King's limner and painter for Scotland in 1823.D. Campbell, ''Edinburgh: A Cultural and Literary History'' (Signal Books, 2003), , pp. 142–3. Nasmyth visited Italy and worked in London, but returned to his native Edinburgh for most of his career. He produced work in a range of forms, including his portrait of Romantic poet Robert Burns, which depicts him against a dramatic Scottish background, but he is chiefly remembered for his landscapes and has been seen as "the founder of the Scottish landscape tradition".I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, fourth edn., 2009), , p. 433. The work of Knox continued the theme of landscape, directly linking it with the Romantic works of Scott, and he was also among the first artists to depict the urban landscape of Glasgow.

Architecture

The Gothic revival in architecture has been seen as an expression of Romanticism, and according to Alvin Jackson, the Scots baronial style was "a Caledonian reading of the gothic". Some of the earliest evidence of a revival in Gothic architecture are from Scotland. Inveraray Castle, constructed from 1746 with design input from William Adam, incorporatesturret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

s into a conventional Palladian-style house. His son Robert Adam's houses in this style include Mellerstain and Wedderburn in Berwickshire and Seton House in East Lothian. The trend is most clearly seen at Culzean Castle, Ayrshire, remodelled by Robert from 1777.

Important for the re-adoption of the Scots Baronial in the early nineteenth century was Abbotsford House, the residence of Scott. Re-built for him from 1816, it became a model for the revival of the style. Common features borrowed from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century houses included battlemented gateways,

Important for the re-adoption of the Scots Baronial in the early nineteenth century was Abbotsford House, the residence of Scott. Re-built for him from 1816, it became a model for the revival of the style. Common features borrowed from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century houses included battlemented gateways, crow-stepped gable

A stepped gable, crow-stepped gable, or corbie step is a stairstep type of design at the top of the triangular gable-end of a building. The top of the parapet wall projects above the roofline and the top of the brick or stone wall is stacked in ...

s, pointed turrets and machicolations

A machicolation (french: mâchicoulis) is a floor opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement, through which stones or other material, such as boiling water, hot sand, quicklime or boiling cooking oil, could be dropped on attackers at t ...

. The style was popular across Scotland and was applied to many relatively modest dwellings by architects such as William Burn (1789–1870), David Bryce (1803–1876),L. Hull, ''Britain's Medieval Castles'' (London: Greenwood, 2006), , p. 154. Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's back ...

(1787–1879), Edward Calvert (c. 1847–1914) and Robert Stodart Lorimer (1864–1929). Examples in urban contexts include the building of Cockburn Street in Edinburgh (from the 1850s) as well as the National Wallace Monument

The National Wallace Monument (generally known as the Wallace Monument) is a 67 metre tower on the shoulder of the Abbey Craig, a hilltop overlooking Stirling in Scotland. It commemorates Sir William Wallace, a 13th- and 14th-century Scottish hero ...

at Stirling (1859–69).M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: from the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), , pp. 276–85. The rebuilding of Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought f ...

as a baronial palace, and its adoption as a royal retreat by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

from 1855–58, confirmed the popularity of the style.

In ecclesiastical architecture, a style similar to that developed in England was adopted. Important figures in this movement included Frederick Thomas Pilkington (1832–98), who developed a new style of church building which accorded with the fashionable High Gothic

High Gothic is a particularly refined and imposing style of Gothic architecture that appeared in northern France from about 1195 until 1250. Notable examples include Chartres Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and ...

, but which adapted it for the worship needs of the Free Church of Scotland. Examples include Barclay Viewforth Church

Barclay Viewforth Church is a parish church of the Church of Scotland in the Presbytery of Edinburgh.

History

Located at the border between the Bruntsfield and Tollcross areas of the city at the junction of Barclay Place and Wright's House ...

, Edinburgh (1862–64).G. Stamp, "The Victorian kirk: Presbyterian architecture in nineteenth century Scotland", in C. Brooks, ed., ''The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), , pp. 108–10. Robert Rowand Anderson (1834–1921), who trained in the office of George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

in London before returning to Edinburgh, worked mainly on small churches in the "First Pointed" (or Early English) style that is characteristic of Scott's former assistants. By 1880, his practice was designing some of the most prestigious public and private buildings in Scotland, such as the Scottish National Portrait Gallery; the Dome of Old College, Medical Faculty and McEwan Hall, Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

; the Central Hotel at Glasgow Central station

, symbol_location = gb

, symbol = rail

, image = Main Concourse at Glasgow Central Station.JPG

, caption = The main concourse

, borough = Glasgow, City of Glasgow

, country ...

; the Catholic Apostolic Church

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in Scotland around 1831 and later spread to Germany and the United States.Mount Stuart House

Mount Stuart House, on the east coast of the Isle of Bute, Scotland, is a country house built in the Gothic Revival style and the ancestral home of the Marquesses of Bute. It was designed by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson for the 3rd Marquess in ...

on the Isle of Bute.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 552.

Music

One characteristic of Romanticism was the conscious creation of bodies of nationalist art music. In Scotland this form was dominant from the late eighteenth century to the early twentieth century.M. Gardiner, ''Modern Scottish Culture'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. 195–6. In the 1790s Robert Burns embarked on an attempt to produce a corpus of Scottish national song, building on the work of antiquarians and musicologists such as William Tytler, James Beattie and Joseph Ritson. Working with music engraver and seller James Johnson, he contributed about a third of the eventual songs of the collection known as the ''Scots Musical Museum

The ''Scots Musical Museum'' was an influential collection of traditional folk music of Scotland published from 1787 to 1803. While it was not the first collection of Scottish folk songs and music, the six volumes with 100 songs in each collected ...

'', issued between 1787 and 1803 in six volumes. Burns collaborated with George Thomson in ''A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs'', published from 1793 to 1818, which adapted Scottish folk songs with "classical" arrangements. Thompson was inspired by hearing Scottish songs sung by visiting Italian castrati

A castrato (Italian, plural: ''castrati'') is a type of classical male singing voice equivalent to that of a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto. The voice is produced by castration of the singer before puberty, or it occurs in one who, due to ...

at the St Cecilia Concerts in Edinburgh. He collected Scottish songs and obtained musical arrangements from the best European composers, who included Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have le ...

and Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

. Burns was employed in editing the lyrics. ''A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs'' was published in five volumes between 1799 and 1818. It helped make Scottish songs part of the European cannon of classical music, while Thompson's work brought elements of Romanticism, such as harmonies based on those of Beethoven, into Scottish classical music. Also involved in the collection and publication of Scottish songs was Scott, whose first literary effort was ''Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border

''Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border'' is an anthology of Border ballads, together with some from north-east Scotland and a few modern literary ballads, edited by Walter Scott. It was first published in 1802, but was expanded in several later ...

'', published in three volumes (1802–03). This collection first drew the attention of an international audience to his work, and some of his lyrics were set to music by Schubert, who also created a setting of Ossian.

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sym ...

, who visited Britain ten times, for a total of twenty months, from 1829. Scotland inspired two of his most famous works, the overture ''Fingal's Cave

Fingal's Cave is a sea cave on the uninhabited island of Staffa, in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, known for its natural acoustics. The National Trust for Scotland owns the cave as part of a national nature reserve. It became known as Finga ...

'' (also known as the ''Hebrides Overture'') and the '' Scottish Symphony'' (Symphony No. 3). On his last visit to England in 1847, he conducted his own ''Scottish Symphony'' with the Philharmonic Orchestra before Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Max Bruch (1838–1920) composed the ''Scottish Fantasy

The ''Scottish Fantasy'' in E-flat major (german: Fantasie für die Violine mit Orchester und Harfe unter freier Benutzung schottischer Volksmelodien), Op. 46, is a composition for violin and orchestra by Max Bruch. Completed in 1880, it was de ...

'' (1880) for violin and orchestra, which includes an arrangement of the tune "Hey Tuttie Tatie", best known for its use in the song ''Scots Wha Hae

"Scots Wha Hae" (English: ''Scots Who Have''; gd, Brosnachadh Bhruis) is a patriotic song of Scotland written using both words of the Scots language and English, which served for centuries as an unofficial national anthem of the country, but h ...

'' by Burns.

By the late nineteenth century, there was in effect a national school of orchestral and operatic music in Scotland. Major composers included Alexander Mackenzie (1847–1935), William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army ...

(1860–1940), Learmont Drysdale

Learmont Drysdale (full name George John Learmont Drysdale; 3 October 1866 – 18 June 1909) was a Scottish composer. During a short career he wrote music inspired by Scotland, particularly the Scottish Borders; this included orchestral music, c ...

(1866–1909), Hamish MacCunn (1868–1916) and John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

(1868–1948). Mackenzie, who studied in Germany and Italy and mixed Scottish themes with German Romanticism, is best known for his three ''Scottish Rhapsodies'' (1879–80, 1911), ''Pibroch'' for violin and orchestra (1889) and the ''Scottish Concerto'' for piano (1897), all involving Scottish themes and folk melodies. Wallace's work included an overture, ''In Praise of Scottish Poesie'' (1894); his pioneering symphonic poem about his namesake, medieval nationalist ''William Wallace AD 1305–1905'' (1905); and a cantata, ''The Massacre of the Macpherson'' (1910).J. Stevenson"William Wallace"

''Allmusic'', retrieved 11 May 2011. Drysdale's work often dealt with Scottish themes, including the overture ''Tam O’ Shanter'' (1890), the cantata ''The Kelpie'' (1891), the tone poem ''A Border Romance'' (1904), and the cantata ''Tamlane'' (1905). MacCunn's overture ''

The Land of the Mountain and the Flood

''The Land of the Mountain and the Flood'' is a concert overture for orchestra, composed by Hamish MacCunn in 1887 and first performed at the Crystal Palace on 5 November of that year."Crystal Palace", ''The Musical Times'', December 1887, p. 726 ...

'' (1887), his ''Six Scotch Dances'' (1896), his operas ''Jeanie Deans

Jeanie Deans is a fictional character in Sir Walter Scott's novel '' The Heart of Midlothian'' first published in 1818. She was one of Scott's most celebrated characters during the 19th century; she was renowned as an example of an honest, uprig ...

'' (1894) and ''Dairmid'' (1897) and choral works on Scottish subjects have been described by I. G. C. Hutchison as the musical equivalent of Abbotsford and Balmoral. McEwen's more overtly national works include ''Grey Galloway'' (1908), the ''Solway Symphony'' (1911) and ''Prince Charlie'', A Scottish Rhapsody (1924).

Historiography

In contrast to Enlightenment histories, which have been seen as attempting to draw general lessons about humanity from history, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder in his ''Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind'' (1784), set out the concept of ''

In contrast to Enlightenment histories, which have been seen as attempting to draw general lessons about humanity from history, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder in his ''Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind'' (1784), set out the concept of ''Volksgeist

''Geist'' () is a German noun with a significant degree of importance in German philosophy. Its semantic field corresponds to English ghost, spirit, mind, intellect. Some English translators resort to using "spirit/mind" or "spirit (mind)" to ...

'', a unique national spirit that drove historical change. As a result, a key element in the influence of Romanticism on intellectual life was the production of national histories. The nature and existence of a national Scottish historiography has been debated among historians. Those authors who consider that such a national history did exist in this period indicate that it can be found outside of the production of major historical narratives, in works of antiquarianism

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

and fiction.

An important element in the emergence of a Scottish national history was an interest in antiquarianism, with figures like John Pinkerton

John Pinkerton (17 February 1758 – 10 March 1826) was a Scottish antiquarian, cartographer, author, numismatist, historian, and early advocate of Germanic racial supremacy theory.

He was born in Edinburgh, as one of three sons to Ja ...

(1758–1826) collecting sources such as ballads, coins, medals, songs and artefacts. Enlightenment historians had tended to react with embarrassment to Scottish history, particularly the feudalism of the Middle Ages and the religious intolerance of the Reformation. In contrast many historians of the early nineteenth century rehabilitated these areas as suitable for serious study. Lawyer and antiquarian Cosmo Innes

Cosmo Nelson Innes FRSE (9 September 1798 – 31 July 1874) was a Scottish advocate, judge, historian and antiquary. He served as Advocate-Depute, Sheriff of Elginshire, and Principal Clerk of Session.

He was a skilled decipherer of ancient ...

, who produced works on ''Scotland in the Middle Ages'' (1860), and ''Sketches of Early Scottish History'' (1861), has been likened to the pioneering history of Georg Heinrich Pertz, one of the first writers to collate the major historical accounts of German history.M. Bently, "Shape and pattern in British historical writing, 1815–1945, in ''S. MacIntyre, J. Maiguashca and A. Pok, eds, ''The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 4: 1800–1945'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 206. Patrick Fraser Tytler's nine-volume history of Scotland (1828–43), particularity his sympathetic view of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

, have led to comparisons with Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis ...

, considered the father of modern scientific historical writing. Tytler was co-founder with Scott of the Bannatyne Society in 1823, which helped further the course of historical research in Scotland. Thomas M'Crie's (1797–1875) biographies of John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

and Andrew Melville, figures generally savaged in the Enlightenment, helped rehabilitate their reputations.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , p. 9. W. F. Skene

William Forbes Skene WS FRSE FSA(Scot) DCL LLD (7 June 1809 – 29 August 1892), was a Scottish lawyer, historian and antiquary.

He co-founded the Scottish legal firm Skene Edwards which was prominent throughout the 20th century but disappeare ...

's (1809–92) three part study of ''Celtic Scotland'' (1886–91) was the first serious investigation of the region and helped spawn the Scottish Celtic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

. Issues of race became important, with Pinkerton, James Sibbald (1745–1803) and John Jamieson (1758–1839) subscribing to a theory of Picto-Gothicism, which postulated a Germanic origin for the Picts and the Scots language.C. Kidd, ''Subverting Scotland's Past: Scottish Whig Historians and the Creation of an Anglo-British Identity 1689–1830'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , p. 251.

Among the most significant intellectual figures associated with Romanticism was

Among the most significant intellectual figures associated with Romanticism was Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

(1795–1881), born in Scotland and later a resident of London. He was largely responsible for bringing the works of German Romantics such as Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friends ...

and Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

to the attention of a British audience.M. Cumming, ''The Carlyle Encyclopedia'' (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004), pp. 200ff and 223. An essayist and historian, he invented the phrase "hero-worship", lavishing largely uncritical praise on strong leaders such as Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

and Napoleon. His '' The French Revolution: A History'' (1837) dramatised the plight of the French aristocracy, but stressed the inevitability of history as a force.M. Anesko, A. Ladd, J. R. Phillips, ''Romanticism and Transcendentalism'' (Infobase Publishing, 2006), , pp. 7–9. With French historian Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and an author on other topics whose major work was a history of France and its culture. His aphoristic style emphasized his anti-clerical republicanism.

In Michelet' ...

, he is associated with the use of the "historical imagination". In Romantic historiography this led to a tendency to emphasise sentiment and identification, inviting readers to sympathise with historical personages and even to imagine interactions with them. In contrast to many continental Romantic historians, Carlyle remained largely pessimistic about human nature and events. He believed that history was a form of prophecy that could reveal patterns for the future. In the late nineteenth century he became one of a number of Victorian sage writers and social commentators.

Romantic writers often reacted against the empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

of Enlightenment historical writing, putting forward the figure of the "poet-historian" who would mediate between the sources of history and the reader, using insight to create more than chronicles of facts. For this reason, Romantic historians such as Thierry saw Walter Scott, who had spent considerable effort uncovering new documents and sources for his novels, as an authority in historical writing. Scott is now seen primarily as a novelist, but also produced a nine-volume biography of Napoleon, and has been described as "the towering figure of Romantic historiography in Transatlantic and European contexts", having a profound effect on how history, particularly that of Scotland, was understood and written. Historians that acknowledged his influence included Chateaubriand, Macaulay, and Ranke.

Science

Romanticism has also been seen as affecting scientific enquiry. Romantic attitudes to science varied, from distrust of the scientific enterprise to endorsing a non-mechanical science that rejected the mathematicised and the abstract theorising associated with Newton. Major trends in continental science associated with Romanticism include ''Naturphilosophie

''Naturphilosophie'' (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German s ...

'', developed by Friedrich Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

(1775–1854), which focused on the necessity of reuniting man with nature, and Humboldtian science

Humboldtian science refers to a movement in science in the 19th century closely connected to the work and writings of German scientist, naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. It maintained a certain ethics of precision and observation, ...

, based on the work of Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

(1769–1859). As defined by Susan Cannon, this form of inquiry placed a stress on observation, accurate scientific instruments and new conceptual tools; disregarded the boundaries between different disciplines; and emphasised working in nature rather than the artificial laboratory.J. L. Heilbron, ''The Oxford Companion To the History of Modern Science'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), , p. 386. Privileging observation above calculation, Romantic scientists were often attracted to the areas where investigation, rather than calculation and theory, was most important, particularly the life sciences, geology, optics and astronomy.W. E. Burns, ''Science in the Enlightenment: An Encyclopedia'' (ABC-CLIO, 2003), , p. xviii.

James Allard identifies the origins of Scottish "Romantic medicine" in the work of Enlightenment figures, particularly the brothers William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

(1718–83) and John Hunter (1728–93), who were, respectively, the leading anatomist and surgeon of their day and in the role of Edinburgh as a major centre of medical teaching and research.J. R. Allard, "Medicine", in J. Faflak and J. M. Wright, eds, ''A Handbook of Romanticism Studies'' (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), , pp. 379–80. Key figures that were influenced by the Hunters' work and by Romanticism include John Brown (1735–88), Thomas Beddoes (1760–1808) and John Barclay (1758–1826). Brown argued in ''Elementa Medicinae'' (1780) that life is an essential "vital energy" or "excitability" and that disease is either the excessive or diminished redistribution of the normal intensity of the human organ, which became known as Brunonianism. This work was highly influential, particularly in Germany, on the development of Naturphilosophie. This work was translated and edited by Beddoes, another graduate of Edinburgh, whose own work, ''Hygeia, or Essays Moral and Medical'' (1807) expanded on these ideas. Following in this vein, Barclay in the 1810 edition of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' identified physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

as the branch of medicine closest to metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

. Also important were the brothers John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(1763–1820) and Charles Bell

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, artist, and philosophical theologian. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves and motor nerves in the spin ...

(1774–1842), who made significant advances in the study of the vascular

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away f ...

and nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes ...

s, respectively.

The University of Edinburgh was also a major supplier of surgeons for the royal navy, and Robert Jameson (1774–1854), Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh, ensured that a large number of these were surgeon-naturalists, who were vital in the Humboldtian and imperial enterprise of investigating nature throughout the world. These included Robert Brown (1773–1858), one of the major figures in the early exploration of Australia. His later use of the microscope paralleled that noted among German students of Naturphilosophie, and he is credited with the discovery of the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

and the first observation of Brownian motion

Brownian motion, or pedesis (from grc, πήδησις "leaping"), is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas).

This pattern of motion typically consists of random fluctuations in a particle's position insi ...

. Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

's work '' Principles of Geology'' (1830) is often seen as the foundation of modern geology. It was indebted to Humboldtian science in its insistence on measurements of nature, and, according to Noah Heringman, retains a much of the "rhetoric of the sublime", which is characteristic of Romantic attitudes to landscape.

Romantic thinking was also evident in the writings of Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller (10 October 1802 – 23/24 December 1856) was a self-taught Scottish geologist and writer, folklorist and an evangelical Christian.

Life and work

Miller was born in Cromarty, the first of three children of Harriet Wright (''b ...

, stonemason and geologist, who followed in the tradition of Naturphilosophie, arguing that nature was a pre-ordained progression towards the human race. Publisher, historian, antiquarian and scientist Robert Chambers (1802–71) became a friend of Scott, writing a biography of him after the author's death. Chambers also became a geologist, researching in Scandinavia and Canada. His most influential work was the anonymously published ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

'' (1844), which was the most comprehensive written argument in favour of evolution before the work of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

(1809–82). His work was strongly influenced by transcendental anatomy

Transcendental anatomy, also known as philosophical anatomy, was a form of comparative anatomy that sought to find ideal patterns and structures common to all organisms in nature. The term originated from naturalist philosophy in the German provin ...

, which, drawing on Goethe and Lorenz Oken

Lorenz Oken (1 August 1779 – 11 August 1851) was a German naturalist, botanist, biologist, and ornithologist.

Oken was born Lorenz Okenfuss (german: Okenfuß) in Bohlsbach (now part of Offenburg), Ortenau, Baden, and studied natural history and ...

(1779–1851), looked for ideal patterns and structure in nature and had been pioneered in Scotland by figures including Robert Knox (1791–1862).

David Brewster

Sir David Brewster KH PRSE FRS FSA Scot FSSA MICE (11 December 178110 February 1868) was a British scientist, inventor, author, and academic administrator. In science he is principally remembered for his experimental work in physical optics ...

(1781–1868), physicist, mathematician and astronomer, undertook key work in optics, where he provided a compromise between Goethe's Naturphilosophie-influenced studies and Newton's system, which Goethe attacked. His work would be important in later biological, geological and astrological discoveries. Diligent measurement in South Africa allowed Thomas Henderson (1798–1844) make the observations that would allow him to be the first to calculate the distance to Alpha Centauri

Alpha Centauri ( Latinized from α Centauri and often abbreviated Alpha Cen or α Cen) is a triple star system in the constellation of Centaurus. It consists of 3 stars: Alpha Centauri A (officially Rigil Kentaurus), Alpha Centa ...

, before returning to Edinburgh to become the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland

Astronomer Royal for Scotland was the title of the director of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh until 1995. It has since been an honorary title.

Astronomers Royal for Scotland

See also

* Edinburgh Astronomical Institution

* City Observatory

* ...

from 1834. Influenced by Humboldt, and much praised by him, was Mary Somerville

Mary Somerville (; , formerly Greig; 26 December 1780 – 29 November 1872) was a Scottish scientist, writer, and polymath. She studied mathematics and astronomy, and in 1835 she and Caroline Herschel were elected as the first female Honorary ...

(1780–1872), mathematician, geographer, physicist, astronomer and one of the few women to gain recognition in science in the period. A major contribution to the "magnetic crusade" declared by Humboldt was made by Scottish-born astronomer John Lamont (1805–79), head of the observatory in Munich, when he found a decennial period (ten-year cycle) in the Earth's magnetic field.

Politics

In the aftermath of the Jacobite risings, a movement to restore Stuart King

In the aftermath of the Jacobite risings, a movement to restore Stuart King James II of England

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

to the throne, the British government enacted a series of laws that attempted to speed the process of the destruction of the clan system. Measures included a ban on the bearing of arms, the wearing of tartan and limitations on the activities of the Episcopalian Church. Most of the legislation was repealed by the end of the eighteenth century as the Jacobite threat subsided.

Soon after, there was a process of the rehabilitation of highland culture. Tartan had already been adopted for highland regiments in the British army, which poor highlanders joined in large numbers until the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

in 1815, but by the nineteenth century it had largely been abandoned by the ordinary people of the region. In the 1820s, tartan and the kilt were adopted by members of the social elite, not just in Scotland, but across Europe.M. Sievers''The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland''

(GRIN Verlag, 2007), , pp. 22–5. The international craze for tartan, and for idealising a romanticised Highlands, was set off by the Ossian cycle and further popularised by the works of Scott. His "staging" of the royal

visit of King George IV to Scotland

The visit of George IV to Scotland in 1822 was the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland in nearly two centuries, the last being by King Charles II for his Scottish coronation in 1651. Government ministers had pressed the King to bring ...

in 1822 and the king's wearing of tartan resulted in a massive upsurge in demand for kilts and tartans that could not be met by the Scottish linen industry. Individual clan tartans was largely defined in this period, and they became a major symbol of Scottish identity. This "Highlandism", by which all of Scotland was identified with the culture of the Highlands, was cemented by Queen Victoria's interest in the country, her adoption of Balmoral as a major royal retreat and her interest in "tartanry".

The romanticisation of the Highlands and the adoption of Jacobitism into mainstream culture have been seen as defusing the potential threat to the Union with England, the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house or ...

and the dominant Whig government. In many countries Romanticism played a major part in the emergence of radical independence movements through the development of national identities. Tom Nairn

Tom Nairn (born 2 June 1932) is a Scottish political theorist and academic. He is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University. He is known as an essayist and a supporter of Scottish ...

argues that Romanticism in Scotland did not develop along the lines seen elsewhere in Europe, leaving a "rootless" intelligentsia, who moved to England or elsewhere and so did not supply a cultural nationalism that could be communicated to the emerging working classes. Graeme Moreton and Lindsay Paterson both argue that the lack of interference of the British state in civil society meant that the middle classes had no reason to object to the union.A. Ichijo, ''Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts Of Europe and the Nation'' (London: Routledge, 2004), , pp. 35–6. Atsuko Ichijo argues that national identity cannot be equated with a movement for independence. Moreton suggests that there was a Scottish nationalism, but that it was expressed in terms of "Unionist nationalism".A. Ichijo, ''Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts Of Europe and the Nation'' (London: Routledge, 2004), , pp. 3–4. A form of political radicalism remained within Scottish Romanticism, surfacing in events like the foundation of the Friends of the People in 1792 and in 1853 the National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights

The National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights was established in 1853. The first body to publicly articulate dissatisfaction with the Union since the Highland Potato Famine and the nationalist revolts in mainland Europe during ...

, which was in effect a federation of romantics, radical churchmen and administrative reformers. However, Scottish identity was not directed into nationalism until the twentieth century.N. Davidson, ''The Origins of Scottish Nationhood'' (Pluto Press, 2008), , p. 187.

Philosophy

The dominant school of philosophy in Scotland in the late eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century is known as Common Sense Realism. It argued that there are certain concepts, such as our existence, the existence of solid objects and some basic moral "first principles", that are intrinsic to our make-up and from which all subsequent arguments and systems of morality must be derived. It can be seen as an attempt to reconcile the new scientific developments of the Enlightenment with religious belief.Paul C. Gutjahr, ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , p. 39. The origins of these arguments are in a reaction to the scepticism that became dominant in the Enlightenment, particularly that articulated by Scottish philosopher

The dominant school of philosophy in Scotland in the late eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century is known as Common Sense Realism. It argued that there are certain concepts, such as our existence, the existence of solid objects and some basic moral "first principles", that are intrinsic to our make-up and from which all subsequent arguments and systems of morality must be derived. It can be seen as an attempt to reconcile the new scientific developments of the Enlightenment with religious belief.Paul C. Gutjahr, ''Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , p. 39. The origins of these arguments are in a reaction to the scepticism that became dominant in the Enlightenment, particularly that articulated by Scottish philosopher David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

(1711–76). This branch of thinking was first formulated by Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May ( O.S. 26 April) 1710 – 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scottish philosopher. He was the founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense and played an integral role in the Scottish Enlightenment. In 1783 he wa ...

(1710–96) in his ''An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense'' (1764). It was popularised in Scotland by figures including Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart (; 22 November 175311 June 1828) was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician. Today regarded as one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment, he was renowned as a populariser of the work of Francis Hut ...