Radar in World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Radar in World War II greatly influenced many important aspects of the conflict. This revolutionary new technology of radio-based detection and tracking was used by both the

In March 1936, the RDF research and development effort was moved to the Bawdsey Research Station located at

In March 1936, the RDF research and development effort was moved to the Bawdsey Research Station located at

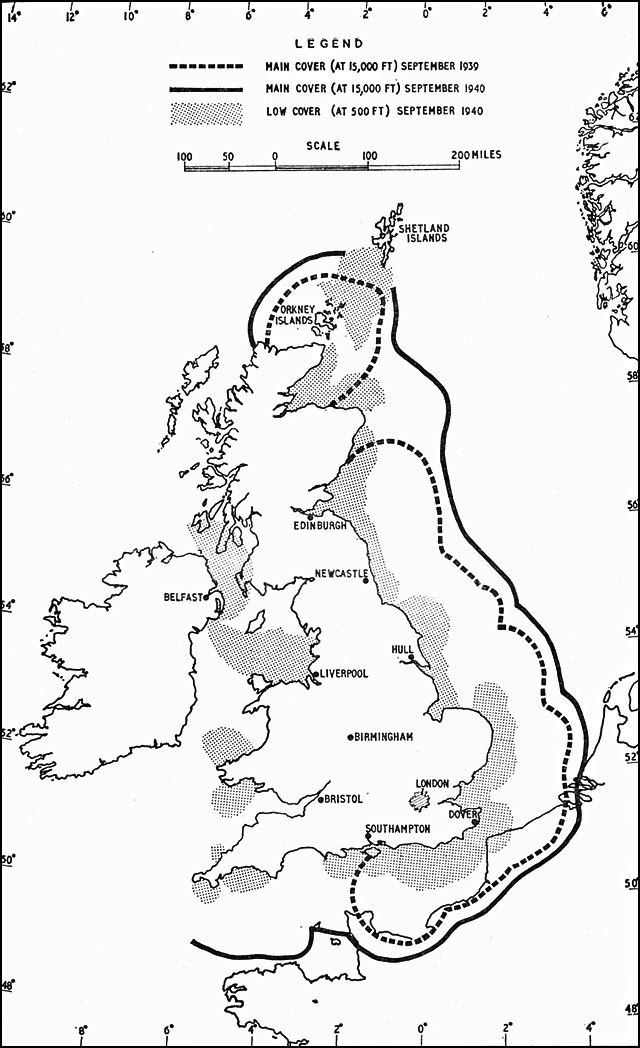

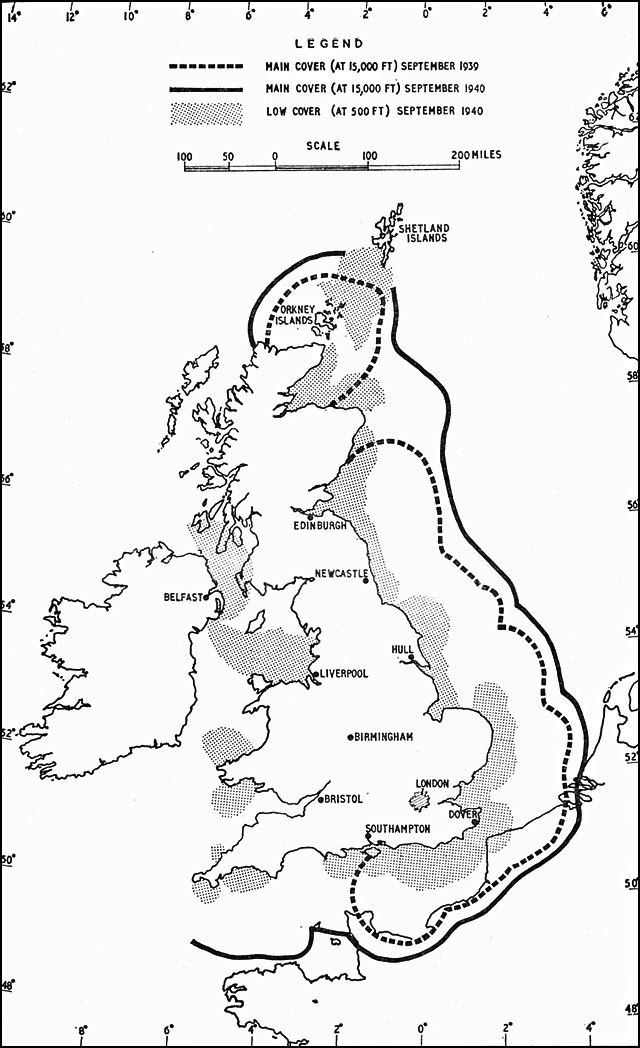

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, several RDF (radar) stations in a system known as ''Chain Home'' (or ''CH'') were constructed along the South and East coasts of Britain, based on the successful model at Bawdsey. CH was a relatively simple system. The transmitting side comprised two 300-ft (90-m)-tall steel towers strung with a series of antennas between them. A second set of 240-ft (73-m)-tall wooden towers was used for reception, with a series of crossed antennas at various heights up to 215 ft (65 m). Most stations had more than one set of each antenna, tuned to operate at different frequencies.

Typical CH operating parameters were:

* Frequency: 20 to 30

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, several RDF (radar) stations in a system known as ''Chain Home'' (or ''CH'') were constructed along the South and East coasts of Britain, based on the successful model at Bawdsey. CH was a relatively simple system. The transmitting side comprised two 300-ft (90-m)-tall steel towers strung with a series of antennas between them. A second set of 240-ft (73-m)-tall wooden towers was used for reception, with a series of crossed antennas at various heights up to 215 ft (65 m). Most stations had more than one set of each antenna, tuned to operate at different frequencies.

Typical CH operating parameters were:

* Frequency: 20 to 30  CH proved highly effective during the

CH proved highly effective during the  To avoid the CH system, the ''Luftwaffe'' adopted other tactics. One was to approach the coastline at very low altitude. This had been anticipated and was countered to some degree with a series of shorter-range stations built right on the coast, known as ''

To avoid the CH system, the ''Luftwaffe'' adopted other tactics. One was to approach the coastline at very low altitude. This had been anticipated and was countered to some degree with a series of shorter-range stations built right on the coast, known as ''

Systems similar to CH were later adapted with a new display to produce the ''

Systems similar to CH were later adapted with a new display to produce the ''

Electric listening device

.

As Oshchepkov was exploring pulsed systems, work continued on CW research at the LEPI. In 1935, the LEPI became a part of the ''Nauchno-issledovatel institut-9'' (NII-9, Scientific Research Institute #9), one of several technical sections under the GAU. With M. A. Bonch-Bruevich as Scientific Director, research continued in CW development. Two promising experimental systems were developed. A VHF set designated ''Bistro'' (Rapid) and the microwave ''Burya'' (Storm). The best features of these were combined into a mobile system called ''Ulavlivatel Samoletov'' (Radio Catcher of Aircraft), soon designated RUS-1 ( РУС-1). This CW, bi-static system used a truck-mounted transmitter operating at 4.7 m (64 MHz) and two truck-mounted receivers.

In June 1937, all of the work in Leningrad on radio-location stopped. The

As Oshchepkov was exploring pulsed systems, work continued on CW research at the LEPI. In 1935, the LEPI became a part of the ''Nauchno-issledovatel institut-9'' (NII-9, Scientific Research Institute #9), one of several technical sections under the GAU. With M. A. Bonch-Bruevich as Scientific Director, research continued in CW development. Two promising experimental systems were developed. A VHF set designated ''Bistro'' (Rapid) and the microwave ''Burya'' (Storm). The best features of these were combined into a mobile system called ''Ulavlivatel Samoletov'' (Radio Catcher of Aircraft), soon designated RUS-1 ( РУС-1). This CW, bi-static system used a truck-mounted transmitter operating at 4.7 m (64 MHz) and two truck-mounted receivers.

In June 1937, all of the work in Leningrad on radio-location stopped. The  During 1940, the LEPI took control of ''Redut'' development, perfecting the critical capability of range measurements. A cathode-ray display, made from an oscilloscope, was used to show range information. In July 1940, the new system was designated RUS-2 ( РУС-2). A transmit-receive device (a duplexer) to allow operating with a common antenna was developed in February 1941. These breakthroughs were achieved at an experimental station at

During 1940, the LEPI took control of ''Redut'' development, perfecting the critical capability of range measurements. A cathode-ray display, made from an oscilloscope, was used to show range information. In July 1940, the new system was designated RUS-2 ( РУС-2). A transmit-receive device (a duplexer) to allow operating with a common antenna was developed in February 1941. These breakthroughs were achieved at an experimental station at

In early 1941, Air Defense recognized the need for radar on their night-fighter aircraft. The requirements were given to Runge at Telefunken, and by the summer a prototype system was tested. Code-named ''Lichtenstein'', this was originally a low-UHF band, (485-MHz), 1.5-kW system in its earliest ''B/C'' model, generally based on the technology now well established by Telefunken for the Würzburg. The design problems were reduction in weight, provision of a good minimum range (very important for air-to-air combat), and an appropriate antenna design. An excellent minimum range of 200 m was achieved by carefully shaping the pulse. The ''Matratze'' (mattress) antenna array in its full form had sixteen dipoles with reflectors (a total of 32 elements), giving a wide searching field and a typical 4-km maximum range (limited by ground clutter and dependent on altitude), but producing a great deal of aerodynamic drag. A rotating phase-shifter was inserted in the transmission lines to produce a twirling beam. The elevation and azimuth of a target relative to the fighter were shown by corresponding positions on a triple-tube CRT display.

In early 1941, Air Defense recognized the need for radar on their night-fighter aircraft. The requirements were given to Runge at Telefunken, and by the summer a prototype system was tested. Code-named ''Lichtenstein'', this was originally a low-UHF band, (485-MHz), 1.5-kW system in its earliest ''B/C'' model, generally based on the technology now well established by Telefunken for the Würzburg. The design problems were reduction in weight, provision of a good minimum range (very important for air-to-air combat), and an appropriate antenna design. An excellent minimum range of 200 m was achieved by carefully shaping the pulse. The ''Matratze'' (mattress) antenna array in its full form had sixteen dipoles with reflectors (a total of 32 elements), giving a wide searching field and a typical 4-km maximum range (limited by ground clutter and dependent on altitude), but producing a great deal of aerodynamic drag. A rotating phase-shifter was inserted in the transmission lines to produce a twirling beam. The elevation and azimuth of a target relative to the fighter were shown by corresponding positions on a triple-tube CRT display.

The first production sets (''Lichtenstein B/C'') became available in February 1942, but were not accepted into combat until September. The ''Nachtjäger'' (night fighter) pilots found to their dismay, that the 32-element ''Matratze'' array was slowing their aircraft up by as much as 50 km/h. In May 1943, a ''B/C''-equipped Ju 88R-1 night fighter aircraft landed in Scotland, which still survives as a restored museum piece; it had been flown into Scotland by a trio of defecting ''Luftwaffe'' pilots. The British immediately recognized that they already had an excellent countermeasure in Window (the chaff used against the ''Würzburg''); in a short time the ''B/C'' was greatly reduced in usefulness.

The first production sets (''Lichtenstein B/C'') became available in February 1942, but were not accepted into combat until September. The ''Nachtjäger'' (night fighter) pilots found to their dismay, that the 32-element ''Matratze'' array was slowing their aircraft up by as much as 50 km/h. In May 1943, a ''B/C''-equipped Ju 88R-1 night fighter aircraft landed in Scotland, which still survives as a restored museum piece; it had been flown into Scotland by a trio of defecting ''Luftwaffe'' pilots. The British immediately recognized that they already had an excellent countermeasure in Window (the chaff used against the ''Würzburg''); in a short time the ''B/C'' was greatly reduced in usefulness.

When the chaff problem was realized by Germany, it was decided to make the wavelength variable, allowing the operator to tune away from chaff returns. In mid-1943, the greatly improved ''Lichtenstein SN-2'' was released, operating with a

When the chaff problem was realized by Germany, it was decided to make the wavelength variable, allowing the operator to tune away from chaff returns. In mid-1943, the greatly improved ''Lichtenstein SN-2'' was released, operating with a  Although Telefunken had not been previously involved with radars of any type for fighter aircraft, in 1944 they started the conversion of a ''Marbach'' 10-cm set for this application. Downed American and British planes were scavenged for radar components; of special interest were the swiveling mechanisms used to scan the beam over the search area. An airborne set with a half-elliptical

Although Telefunken had not been previously involved with radars of any type for fighter aircraft, in 1944 they started the conversion of a ''Marbach'' 10-cm set for this application. Downed American and British planes were scavenged for radar components; of special interest were the swiveling mechanisms used to scan the beam over the search area. An airborne set with a half-elliptical

In the years prior to World War II, Japan had knowledgeable researchers in the technologies necessary for radar; they were especially advanced in magnetron development. However, a lack of appreciation of radar's potential and rivalry between army, navy and civilian research groups meant Japan's development was slow. It was not until November 1941, just days before the

In the years prior to World War II, Japan had knowledgeable researchers in the technologies necessary for radar; they were especially advanced in magnetron development. However, a lack of appreciation of radar's potential and rivalry between army, navy and civilian research groups meant Japan's development was slow. It was not until November 1941, just days before the

LW/AW

Mark I.'' From this, the ''LW/AW Mark II'' resulted; about 130 of these air-transportable sets were built and used by the United States and Australian military forces in the early island landings in the South Pacific, as well as by the British in

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, which had evolved independently in a number of nations during the mid 1930s. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, both Great Britain and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

had functioning radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

systems. In Great Britain, it was called RDF, Range and Direction Finding

The history of radar (where radar stands for radio detection and ranging) started with experiments by Heinrich Hertz in the late 19th century that showed that radio waves were reflected by metallic objects. This possibility was suggested in Jame ...

, while in Germany the name ''Funkmeß'' (radio-measuring) was used, with apparatuses called ''Funkmessgerät'' (radio measuring device).

By the time of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

in mid-1940, the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) had fully integrated RDF as part of the national air defence.

In the United States, the technology was demonstrated during December 1934, although it was only when war became likely that the U.S. recognized the potential of the new technology, and began development of ship- and land-based systems. The first of these were fielded by the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

in early 1940, and a year later by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. The acronym RADAR (for Radio Detection And Ranging) was coined by the U.S. Navy in 1940, and the term "radar" became widely used.

While the benefits of operating in the microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

portion of the radio spectrum

The radio spectrum is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum with frequencies from 0 Hz to 3,000 GHz (3 THz). Electromagnetic waves in this frequency range, called radio waves, are widely used in modern technology, particul ...

were known, transmitters for generating microwave signals of sufficient power were unavailable; thus, all early radar systems operated at lower frequencies (e.g., HF or VHF

Very high frequency (VHF) is the ITU designation for the range of radio frequency electromagnetic waves (radio waves) from 30 to 300 megahertz (MHz), with corresponding wavelengths of ten meters to one meter.

Frequencies immediately below VHF ...

). In February 1940, Great Britain developed the resonant-cavity magnetron, capable of producing microwave power in the kilowatt range, opening the path to second-generation radar systems.

After the Fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

, it was realised in Great Britain that the manufacturing capabilities of the United States were vital to success in the war; thus, although America was not yet a belligerent, Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

directed that the technological secrets of Great Britain be shared in exchange for the needed capabilities. In the summer of 1940, the Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

visited the United States. The cavity magnetron was demonstrated to Americans at RCA, Bell Labs, etc. It was 100 times more powerful than anything they had seen. Bell Labs was able to duplicate the performance, and the Radiation Laboratory at MIT was established to develop microwave radars. The magnetron was later described by American military scientists as "the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores".

In addition to Great Britain, Germany, and the United States, wartime radars were also developed and used by Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

.

United Kingdom

Research leading to RDF technology in the United Kingdom was begun by SirHenry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

's Aeronautical Research Committee

The Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (ACA) was a UK agency founded on 30 April 1909, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. In 1919 it was renamed the Aeronautical Research Committee, later becoming the Aeronautical ...

in early 1935, responding to the urgent need to counter German bomber attacks. Robert A. Watson-Watt at the Radio Research Station, Slough, was asked to investigate a radio-based "death ray". In response, Watson-Watt and his scientific assistant, Arnold F. Wilkins, replied that it might be more practical to use radio to detect and track enemy aircraft. On 26 February 1935, a preliminary test, commonly called the Daventry Experiment

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the of ...

, showed that radio signals reflected from an aircraft could be detected. Research funds were quickly allocated, and a development project was started in great secrecy on the Orford Ness

Orford Ness is a cuspate foreland shingle spit on the Suffolk coast in Great Britain, linked to the mainland at Aldeburgh and stretching along the coast to Orford and down to North Weir Point, opposite Shingle Street. It is divided from the m ...

Peninsula in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

. E. G. Bowen was responsible for developing the pulsed transmitter. On 17 June 1935, the research apparatus successfully detected an aircraft at a distance of 17 miles. In August, A. P. Rowe

Albert Percival Rowe, Order of the British Empire, CBE (23 March 1898 – 25 May 1976), often known as Jimmy Rowe or A. P. Rowe, was a radar pioneer and university vice-chancellor. A British physicist and senior research administrator, he played ...

, representing the Tizard Committee, suggested the technology be code-named RDF, meaning Range and Direction Finding

The history of radar (where radar stands for radio detection and ranging) started with experiments by Heinrich Hertz in the late 19th century that showed that radio waves were reflected by metallic objects. This possibility was suggested in Jame ...

.

Air Ministry

In March 1936, the RDF research and development effort was moved to the Bawdsey Research Station located at

In March 1936, the RDF research and development effort was moved to the Bawdsey Research Station located at Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor stands at a prominent position at the mouth of the River Deben close to the village of Bawdsey in Suffolk, England, about northeast of London.

Built in 1886, it was enlarged in 1895 as the principal residence of Sir William C ...

in Suffolk. While this operation was under the Air Ministry, the Army and Navy became involved and soon initiated their own programs.

At Bawdsey, engineers and scientists evolved the RDF technology, but Watson-Watt, the head of the team, turned from the technical side to developing a practical machine/human user interface. After watching a demonstration in which operators were attempting to locate an "attacking" bomber, he noticed that the primary problem was not technological, but information management and interpretation. Following Watson-Watt's advice, by early 1940, the RAF had built up a layered control organization that efficiently passed information along the chain of command, and was able to track large numbers of aircraft and direct interceptors

An interceptor aircraft, or simply interceptor, is a type of fighter aircraft designed specifically for the defensive interception role against an attacking enemy aircraft, particularly bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Aircraft that are ca ...

to them.

Immediately after the war began in September 1939, the Air Ministry RDF development at Bawdsey was temporarily relocated to University College, Dundee

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

in Scotland. A year later, the operation moved to near Worth Matravers in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

on the southern coast of England, and was named the Telecommunications Research Establishment

The Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) was the main United Kingdom research and development organization for radio navigation, radar, infra-red detection for heat seeking missiles, and related work for the Royal Air Force (RAF) ...

(TRE). In a final move, the TRE relocated to Malvern College

Malvern College is an Independent school (United Kingdom), independent coeducational day and boarding school in Malvern, Worcestershire, Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It is a public school (United Kingdom), public school in the British sen ...

in Great Malvern

Great Malvern is an area of the spa town of Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It lies at the foot of the Malvern Hills, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, on the eastern flanks of the Worcestershire Beacon and North Hill, and ...

.

Some of the major RDF/radar equipment used by the Air Ministry is briefly described. All of the systems were given the official designation Air Ministry Experimental Station

AMES, short Air Ministry Experimental Station, was the name given to the British Air Ministry's radar development team at Bawdsey Manor (afterwards RAF Bawdsey) in the immediate pre-World War II era. The team was forced to move on three occasions ...

(AMES) plus a Type number; most of these are listed in this link.

Chain Home

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, several RDF (radar) stations in a system known as ''Chain Home'' (or ''CH'') were constructed along the South and East coasts of Britain, based on the successful model at Bawdsey. CH was a relatively simple system. The transmitting side comprised two 300-ft (90-m)-tall steel towers strung with a series of antennas between them. A second set of 240-ft (73-m)-tall wooden towers was used for reception, with a series of crossed antennas at various heights up to 215 ft (65 m). Most stations had more than one set of each antenna, tuned to operate at different frequencies.

Typical CH operating parameters were:

* Frequency: 20 to 30

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, several RDF (radar) stations in a system known as ''Chain Home'' (or ''CH'') were constructed along the South and East coasts of Britain, based on the successful model at Bawdsey. CH was a relatively simple system. The transmitting side comprised two 300-ft (90-m)-tall steel towers strung with a series of antennas between them. A second set of 240-ft (73-m)-tall wooden towers was used for reception, with a series of crossed antennas at various heights up to 215 ft (65 m). Most stations had more than one set of each antenna, tuned to operate at different frequencies.

Typical CH operating parameters were:

* Frequency: 20 to 30 megahertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that one ...

(MHz) (15 to 10 metres)

* Peak power: 350 kilowatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named after James ...

(kW) (later 750 kW)

* Pulse repetition frequency

The pulse repetition frequency (PRF) is the number of pulses of a repeating signal in a specific time unit. The term is used within a number of technical disciplines, notably radar.

In radar, a radio signal of a particular carrier frequency is tu ...

: 25 and 12.5 pps

* Pulse length: 20 microseconds

A microsecond is a unit of time in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one millionth (0.000001 or 10−6 or ) of a second. Its symbol is μs, sometimes simplified to us when Unicode is not available.

A microsecond is equal to 1000 ...

(μs)

CH output was read with an oscilloscope

An oscilloscope (informally a scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying electrical voltages as a two-dimensional plot of one or more signals as a function of time. The main purposes are to display repetiti ...

. When a pulse was sent from the broadcast towers, a visible line travelled horizontally across the screen very rapidly. The output from the receiver was amplified and fed into the vertical axis of the scope, so a return from an aircraft would deflect the beam upward. This formed a spike on the display, and the distance from the left side – measured with a small scale on the bottom of the screen – would give target range. By rotating the receiver goniometer

A goniometer is an instrument that either measures an angle or allows an object to be rotated to a precise angular position. The term goniometry derives from two Greek words, γωνία (''gōnía'') 'angle' and μέτρον (''métron'') ' m ...

connected to the antennas, the operator could estimate the direction to the target (this was the reason for the cross shaped antennas), while the height of the vertical displacement indicated formation size. By comparing the strengths returned from the various antennas up the tower, altitude could be gauged with some accuracy.

CH proved highly effective during the

CH proved highly effective during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, and was critical in enabling the RAF to defeat the much larger ''Luftwaffe'' forces. Whereas the ''Luftwaffe'' relied on, often out of date, reconnaissance data and fighter sweeps, the RAF knew with a high degree of accuracy Luftwaffe formation strengths and intended targets. The sector stations were able to send the required number of interceptors, often only in small numbers. CH acted as a force multiplier

In military science, force multiplication or a force multiplier is a factor or a combination of factors that gives personnel or weapons (or other hardware) the ability to accomplish greater feats than without it. The expected size increase req ...

, allowing the husbanding of resources, both human and material, and only needing to scramble

Scramble, Scrambled, or Scrambling may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Games

* ''Scramble'' (video game), a 1981 arcade game

Music Albums

* ''Scramble'' (album), an album by Atlanta-based band the Coathangers

* ''Scrambles'' (album)

...

when attack was imminent. This greatly reduced pilot and aircraft fatigue.

Very early in the battle, the ''Luftwaffe'' made a series of small but effective raids on several stations, including Ventnor

Ventnor () is a seaside resort and civil parish established in the Victorian era on the southeast coast of the Isle of Wight, England, from Newport. It is situated south of St Boniface Down, and built on steep slopes leading down to the sea. ...

, but they were repaired quickly. In the meantime, the operators broadcast radar-like signals from neighbouring stations in order to fool the Germans that coverage continued. The Germans' attacks were sporadic and short-lived. The German High Command apparently never understood the importance of radar to the RAF's efforts, or they would have assigned these stations a much higher priority. Greater disruption was caused by destroying the teletype

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Init ...

and landline links of the vulnerable above-ground control huts and the power cables to the masts than by attacking the open latticework towers themselves.

Chain Home Low

Chain Home Low (CHL) was the name of a British early warning radar system operated by the RAF during World War II. The name refers to CHL's ability to detect aircraft flying at altitudes below the capabilities of the original Chain Home (CH) ra ...

'' (''CHL''). These systems had been intended for naval gun-laying and known as Coastal Defence (CD), but their narrow beams also meant that they could sweep an area much closer to the ground without "seeing" the reflection of the ground or water – known as '' clutter''. Unlike the larger CH systems, the CHL broadcast antenna and receiver had to be rotated; this was done manually on a pedal-crank system by members of the WAAF WAAF may refer to:

* w3af, (short for web application attack and audit framework), an open-source web application security scanner

* Women's Auxiliary Air Force, a British military service in World War II

** Waaf, a member of the service

* WAAF ( ...

until the system was motorised in 1941.

Ground-Controlled Intercept

Ground-Controlled Intercept Ground-controlled interception (GCI) is an air defence tactic whereby one or more radar stations or other observational stations are linked to a command communications centre which guides interceptor aircraft to an airborne target. This tactic was p ...

'' (GCI) stations in January 1941. In these systems, the antenna was rotated mechanically, followed by the display on the operator's console. That is, instead of a single line across the bottom of the display from left to right, the line was rotated around the screen at the same speed as the antenna was turning.

The result was a 2-D display of the air space around the station with the operator in the middle, with all the aircraft appearing as dots in the proper location in space. Called ''plan position indicator

A plan position indicator (PPI) is a type of radar display that represents the radar antenna in the center of the display, with the distance from it and height above ground drawn as concentric circles. As the radar antenna rotates, a radial trac ...

s'' (PPI), these simplified the amount of work needed to track a target on the operator's part. Philo Taylor Farnsworth

Philo Taylor Farnsworth (August 19, 1906 – March 11, 1971) was an American inventor and television pioneer. He made many crucial contributions to the early development of all-electronic television. He is best known for his 1927 invention of t ...

refined a version of his picture tube (cathode ray tube

A cathode-ray tube (CRT) is a vacuum tube containing one or more electron guns, which emit electron beams that are manipulated to display images on a phosphorescent screen. The images may represent electrical waveforms ( oscilloscope), ...

, or CRT) and called it an "Iatron". It could store an image for milliseconds to minutes (even hours). One version that kept an image alive about a second before fading, proved to be a useful addition to the evolution of radar. This slow-to-fade display tube was used by air traffic controllers from the very beginning of radar.

Airborne Intercept

The ''Luftwaffe'' took to avoiding intercepting fighters by flying at night and in bad weather. Although the RAF control stations were aware of the location of the bombers, there was little they could do about them unless fighter pilots made visual contact. This problem had already been foreseen, and a successful programme, started in 1936 byEdward George Bowen

Edward George "Taffy" Bowen, CBE, FRS (14 January 1911 – 12 August 1991) was a Welsh physicist who made a major contribution to the development of radar. He was also an early radio astronomer, playing a key role in the establishment of radio ...

, developed a miniaturized RDF system suitable for aircraft, the on-board ''Airborne Interception Radar'' (AI) set (Watson-Watt called the CH sets the RDF-1 and the AI the RDF-2A). Initial AI sets were first made available to the RAF in 1939 and fitted to Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until ...

aircraft (replaced quickly by Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufort ...

s). These measures greatly increased Luftwaffe loss rates.

Later in the war, British Mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

night intruder aircraft were fitted with AI Mk VIII and later derivatives, which with ''Serrate'' allowed them to track down German night fighters from their '' Lichtenstein'' signal emissions, as well as a device named ''Perfectos

Perfectos was a radio device used by Royal Air Force's night fighters during the Second World War to detect German aircraft. It worked by triggering '' Luftwaffe's'' FuG 25a Erstling identification friend or foe (IFF) system and then using the re ...

'' that tracked German IFF. As a countermeasure, the German night fighters employed ''Naxos ZR'' radar signal detectors.

Air-Surface Vessel

While testing the AI radars near Bawdsey Manor, Bowen's team noticed the radar generated strong returns from ships and docks. This was due to the vertical sides of the objects, which formed excellent partialcorner reflector

A corner reflector is a retroreflector consisting of three mutually perpendicular, intersecting flat surfaces, which reflects waves directly towards the source, but translated. The three intersecting surfaces often have square shapes. Radar co ...

s, allowing detection at several miles range. The team focussed on this application for much of 1938.

The Air-Surface Vessel Mark I, using electronics similar to those of the AI sets, was the first aircraft-carried radar to enter service, in early 1940. It was quickly replaced by the improved Mark II, which included side-scanning antennas that allowed the aircraft to sweep twice the area in a single pass. The later ASV Mk. II had the power needed to detect submarines on the surface, eventually making such operations suicidal.

Centimetric

The improvements to the cavitymagnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field while ...

by John Randall and Harry Boot

Henry Albert Howard Boot (29 July 1917 – 8 February 1983) was an English physicist who with Sir John Randall and James Sayers developed the cavity magnetron, which was one of the keys to the Allied victory in the Second World War.

Biograph ...

of Birmingham University

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

in early 1940 marked a major advance in radar capability. The resulting magnetron was a small device that generated high-power microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ra ...

frequencies and allowed the development of practical centimetric radar that operated in the SHF radio frequency band from 3 to 30 GHz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that one he ...

(wavelengths of 10 to 1 cm). Centimetric radar enables the detection of much smaller objects and the use of much smaller antennas than the earlier, lower frequency radars. A radar with a wavelength of 2 meters (VHF band, 150 MHz) cannot detect objects that are much smaller than 2 meters and requires an antenna whose size is on the order of 2 meters (an awkward size for use on aircraft). In contrast, a radar with a 10 cm wavelength can detect objects 10 cm in size with a reasonably-sized antenna.

In addition a tuneable local oscillator and a mixer for the receiver were essential. These were targeted developments, the former by R W Sutton who developed the NR89 reflex klystron, or "Sutton tube". The latter by H W B Skinner who developed the 'cat's whisker' crystal.

At the end of 1939 when the decision was made to develop 10 cm radar, there were no suitable active devices available - no high power magnetron, no reflex klystron, no proven microwave crystal mixer, and no TR cell. By mid-1941, Type 271, the first Naval S-band radar, was in operational use.

The cavity magnetron was perhaps the single most important invention in the history of radar. In the Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

during September 1940, it was given free to the U.S., along with other inventions, such as jet technology, in exchange for American R&D and production facilities; the British urgently needed to produce the magnetron in large quantities. Edward George Bowen

Edward George "Taffy" Bowen, CBE, FRS (14 January 1911 – 12 August 1991) was a Welsh physicist who made a major contribution to the development of radar. He was also an early radio astronomer, playing a key role in the establishment of radio ...

was attached to the mission as the RDF lead. This led to the creation of the Radiation Laboratory (Rad Lab) based at MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

to further develop the device and usage. Half of the radars deployed during World War II were designed at the Rad Lab, including over 100 different systems costing US$1.5 billion.

When the cavity magnetron was first developed, its use in microwave RDF sets was held up because the duplexer

A duplexer is an electronic device that allows bi-directional ( duplex) communication over a single path. In radar and radio communications systems, it isolates the receiver from the transmitter while permitting them to share a common antenna. ...

s for VHF were destroyed by the new higher-powered transmitter. This problem was solved in early 1941 by the transmit-receive (T-R) switch developed at the Clarendon Laboratory

The Clarendon Laboratory, located on Parks Road within the Science Area in Oxford, England (not to be confused with the Clarendon Building, also in Oxford), is part of the Department of Physics at Oxford University. It houses the atomic and ...

of Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, allowing a pulse transmitter and receiver to share the same antenna without affecting the receiver.

The combination of magnetron, T-R switch, small antenna and high resolution allowed small, powerful radars to be installed in aircraft. Maritime patrol {{Unreferenced, date=March 2008

Maritime patrol is the task of monitoring areas of water. Generally conducted by military and law enforcement agencies, maritime patrol is usually aimed at identifying human activities.

Maritime patrol refers to ac ...

aircraft could detect objects as small as submarine periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

s, allowing aircraft to track and attack submerged submarines, where before only surfaced submarines could be detected. However, according to the latest reports on the history U.S. Navy periscope detection the first minimal possibilities for periscope detection appeared only during 50's and 60's and the problem was not completely solved even on the turn of the millennium. In addition, radar could detect the submarine at a much greater range than visual observation, not only in daylight but at night, when submarines had previously been able to surface and recharge their batteries safely. Centimetric contour mapping radars such as '' H2S'', and the even higher-frequency American-created H2X

H2X, officially known as the AN/APS-15, was an American ground scanning radar system used for blind bombing during World War II. It was a development of the British H2S radar, the first ground mapping radar to be used in combat. It was also kn ...

, allowed new tactics in the strategic bombing campaign. Centimetric gun-laying radars were much more accurate than older technology; radar improved Allied naval gunnery and, together with the proximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, an ...

, made anti-aircraft guns much more effective. The two new systems used by anti-aircraft batteries are credited with destroying many V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb or doodlebug and in Germany ...

s in the late summer of 1944.

British Army

During Air Ministry RDF development in Bawdsey, an Army detachment was attached to initiate its own projects. These programmes were for a Gun Laying (GL) system to assist aiming antiaircraft guns andsearchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s and a Coastal Defense (CD) system for directing coastal artillery. The Army detachment included W. A. S. Butement and P. E. Pollard who, in 1930, demonstrated a radio-based detection apparatus that was not further pursued by the Army.

When war started and Air Ministry activities were relocated to Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, the Army detachment became part of a new developmental centre at Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon Rive ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

. John D. Cockcroft, a physicist from Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, who was awarded a Nobel Prize after the war for work in nuclear physics, became Director. With its greater remit, the facility became the Air Defence Research and Development Establishment (ADRDE) in mid-1941. A year later, the ADRDE relocated to Great Malvern

Great Malvern is an area of the spa town of Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It lies at the foot of the Malvern Hills, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, on the eastern flanks of the Worcestershire Beacon and North Hill, and ...

, in Worcestershire

Worcestershire ( , ; written abbreviation: Worcs) is a county in the West Midlands of England. The area that is now Worcestershire was absorbed into the unified Kingdom of England in 927, at which time it was constituted as a county (see H ...

. In 1944, this was redesignated the Radar Research and Development Establishment (RRDE).

Transportable Radio Unit

While at Bawdsey, the Army detachment developed a ''Gun Laying'' ("GL") system termed ''Transportable Radio Unit'' (''TRU''). Pollard was project leader. Operating at 60 MHz (6-m) with 50-kW power, the TRU had two vans for the electronic equipment and a generator van; it used a 105-ft portable tower to support a transmitting antenna and two receiving antennas. A prototype was tested in October 1937, detecting aircraft at 60-miles range; production of 400 sets designated GL Mk. I began in June 1938. The Air Ministry adopted some of these sets to augment the CH network in case of enemy damage. GL Mk. I sets were used overseas by the British Army in Malta and Egypt in 1939–40. Seventeen sets were sent to France with the British Expeditionary Force; while most were destroyed at theDunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allies of World War II, Allied soldiers during the World War II, Second World War from the bea ...

in late May 1940, a few were captured intact, giving the Germans an opportunity to examine British RDF kit. An improved version, GL Mk. II, was used throughout the war; some 1,700 sets were put into service, including over 200 supplied to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. Operational research

Operations research ( en-GB, operational research) (U.S. Air Force Specialty Code: Operations Analysis), often shortened to the initialism OR, is a discipline that deals with the development and application of analytical methods to improve decis ...

found that anti-aircraft guns using GL averaged 4,100 rounds fired per hit, compared with about 20,000 rounds for predicted fire

Predicted fire (originally called ''map shooting'') is a tactical technique for the use of artillery, enabling it to fire for effect without alerting the enemy with ranging shots or a lengthy preliminary bombardment. The guns are laid using detail ...

using a conventional director.

Coastal Defence

In early 1938, Alan Butement began the development of a ''Coastal Defence'' (''CD'') system that involved some of the most advanced features in the evolving technology. The 200 MHz transmitter and receiver already being developed for the AI and ASV sets of the Air Defence were used, but, since the CD would not be airborne, more power and a much largerantenna

Antenna ( antennas or antennae) may refer to:

Science and engineering

* Antenna (radio), also known as an aerial, a transducer designed to transmit or receive electromagnetic (e.g., TV or radio) waves

* Antennae Galaxies, the name of two collid ...

were possible. Transmitter power was increased to 150 kW. A dipole

In physics, a dipole () is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs in two ways:

*An electric dipole deals with the separation of the positive and negative electric charges found in any electromagnetic system. A simple example of this system ...

array high and wide, was developed, giving much narrower beams and higher gain. This "broadside" array was rotated 1.5 revolutions per minute, sweeping a field covering 360 degrees. Lobe switching was incorporated in the transmitting array, giving high directional accuracy. To analyze system capabilities, Butement formulated the first mathematical relationship that later became the well-known "radar range equation".

Although initially intended for detecting and directing fire at surface vessels, early tests showed that the CD set had much better capabilities for detecting aircraft at low altitudes than the existing Chain Home. Consequently, CD was also adopted by the RAF to augment the CH stations; in this role, it was designated ''Chain Home Low

Chain Home Low (CHL) was the name of a British early warning radar system operated by the RAF during World War II. The name refers to CHL's ability to detect aircraft flying at altitudes below the capabilities of the original Chain Home (CH) ra ...

'' (''CHL'').

Centimetric gun-laying

When the cavity magnetron became practicable, the ADEE co-operated with TRE in utilising it in an experimental 20 cm GL set. This was first tested and found to be too fragile for army field use. The ADEE became the ADRDE in early 1941, and started the development of the ''GL3B''. All of the equipment, including the power generator, was contained in a protected trailer, topped with two 6-foot dish transmitting and receiving antennas on a rotating base, as the transmit-receive (T-R) switch allowing a single antenna to perform both functions had not yet been perfected. Similar microwave gun-laying systems were being developed in Canada (the ''GL3C'') and in America (eventually designated ''SCR-584''). Although about 400 of the ''GL3B'' sets were manufactured, it was the American version that was most numerous in the defense of London during the V-1 attacks.Royal Navy

The Experimental Department of His Majesty's Signal School (HMSS) had been present at early demonstrations of the work conducted at Orfordness and Bawdsey Manor. Located atPortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

, the Experimental Department had an independent capability for developing wireless valves (vacuum tubes), and had provided the tubes used by Bowden in the transmitter at Orford Ness. With excellent research facilities of its own, the Admiralty-based its RDF development at the HMSS. This remained in Portsmouth until 1942, when it was moved inland to safer locations at Witley and Haslemere

The town of Haslemere () and the villages of Shottermill and Grayswood are in south west Surrey, England, around south west of London. Together with the settlements of Hindhead and Beacon Hill, they comprise the civil parish of Haslemere in ...

in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

. These two operations became the Admiralty Signal Establishment (ASE).

A few representative radars are described. Note that the type numbers are not sequential by date.

Surface Warning/Gun Control

The Royal Navy's first successful RDF was the '' Type 79Y Surface Warning'', tested at sea in early 1938. John D. S. Rawlinson was the project director. This 43-MHz (7-m), 70-kW set used fixed transmitting and receiving antennas and had a range of 30 to 50 miles, depending on the antenna heights. By 1940, this became the '' Type 281'', increased in frequency to 85 MHz (3.5 m) and power to between 350 and 1,000 kW, depending on the pulse width. With steerable antennas, it was also used for Gun Control. This was first used in combat in March 1941 with considerable success. ''Type 281B'' used a common transmitting and receiving antenna. The ''Type 281'', including the B-version, was the most battle-tested metric system of the Royal Navy throughout the war.Air Search/Gunnery Director

In 1938, John F. Coales began the development of 600-MHz (50-cm) equipment. The higher frequency allowed narrower beams (needed for air search) and antennas more suitable for shipboard use. The first 50-cm set was Type 282. With 25-kW output and a pair ofYagi antenna Yagi may refer to:

Places

* Yagi, Kyoto, in Japan

* Yagi (Kashihara), in Nara Prefecture, Japan

* Yagi-nishiguchi Station, in Kashihara, Nara, Japan

* Kami-Yagi Station, a JR-West Kabe Line station located in 3-chōme, Yagi, Asaminami-ku, Hiroshima ...

s incorporating lobe switching, it was trialed in June 1939. This set detected low-flying aircraft at 2.5 miles and ships at 5 miles. In early 1940, 200 sets were manufactured. To use the Type 282 as a rangefinder for the main armament, an antenna with a large cylindrical parabolic reflector and 12 dipoles was used. This set was designated Type 285 and had a range of 15 miles. Types 282 and Type 285 were used with Bofors 40 mm gun Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

*Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 1990s

...

s. Type 283 and Type 284 were other 50-cm gunnery director systems.

Type 289 was developed based upon Dutch pre-war radar technology and used a Yagi-antenna. With an improved RDF design it controlled Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns (seElectric listening device

.

Microwave Warning/Fire Control

The critical problem of submarine detection required RDF systems operating at higher frequencies than the existing sets because of a submarine's smaller physical size than most other vessels. When the first cavity magnetron was delivered to the TRE, a demonstrationbreadboard

A breadboard, solderless breadboard, or protoboard is a construction base used to build semi-permanent prototypes of electronic circuits. Unlike a perfboard or stripboard, breadboards do not require soldering or destruction of tracks and are h ...

was built and demonstrated to the Admiralty. In early November 1940, a team from Portsmouth under S. E. A. Landale was set up to develop a 10-cm surface-warning set for shipboard use. In December, an experimental apparatus tracked a surfaced submarine at 13 miles range.

At Portsmouth, the team continued development, fitting antennas behind cylindrical parabolas (called "cheese" antennas) to generate a narrow beam that maintained contact as the ship rolled. Designated Type 271 radar

The Type 271 was a surface search radar used by the Royal Navy and allies during World War II. The first widely used naval microwave-frequency system, it was equipped with an antenna small enough to allow it to be mounted on small ships like ...

, the set was tested in March 1941, detecting the periscope of a submerged submarine at almost a mile. The set was deployed in August 1941, just 12 months after the first apparatus was demonstrated. On November 16, the first German submarine was sunk after being detected by a Type 271.

The initial Type 271 primarily found service on smaller vessels. At ASE Witley, this set was modified to become Type 272 and Type 273 for larger vessels. Using larger reflectors, the Type 273 also effectively detected low-flying aircraft, with a range up to 30 miles. This was the first Royal Navy radar with a plan-position indicator

A plan position indicator (PPI) is a type of radar display that represents the radar antenna in the center of the display, with the distance from it and height above ground drawn as concentric circles. As the radar antenna rotates, a radial tra ...

.

Further development led to the Type 277 radar

The Type 277 was a surface search and secondary aircraft early warning radar used by the Royal Navy and allies during World War II and the post-war era. It was a major update of the earlier Type 271 radar, offering much more power, better signal ...

, with almost 100 times the transmitter power. In addition to the microwave detection sets, Coales developed the Type 275 and Type 276 microwave fire-control sets. Magnetron refinements resulted in 3.2-cm (9.4-GHz) devices generating 25-kW peak power. These were used in the Type 262 fire-control radar and Type 268 target-indication and navigation radar.

United States

In 1922, A. Hoyt Taylor andLeo C. Young

Leo C. Young (12 January 1891 – 16 January 1981) was an American radio engineer who had many accomplishments during a long career at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Although self-educated, he was a member of a small, creative team which some ...

, then with the U.S. Navy Aircraft Radio Laboratory, noticed that a ship crossing the transmission path of a radio link produced a slow fading in and out of the signal. They reported this as a Doppler-beat interference with potential for detecting the passing of a vessel, but it was not pursued. In 1930, Lawrence A. Hyland. working for Taylor at the Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. It was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, applied research, technologic ...

(NRL) noted the same effect from a passing airplane. This was officially reported by Taylor. Hyland, Taylor, and Young were granted a patent (U.S. No. 1981884, 1934) for a "System for detecting objects by radio". It was recognized that detection also needed range measurement, and funding was provided for a pulsed transmitter. This was assigned to a team led by Robert M. Page, and in December 1934, a breadboard apparatus successfully detected an aircraft at a range of one mile.

The Navy, however, ignored further development, and it was not until January 1939, that their first prototype system, the 200-MHz (1.5-m) ''XAF'', was tested at sea. The Navy coined the acronym RAdio Detection And Ranging (RADAR), and in late 1940, ordered this to be exclusively used.

Taylor's 1930 report had been passed on to the U.S. Army's Signal Corps Laboratories Signal Corps Laboratories (SCL) was formed on June 30, 1930, as part of the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Through the years, the SCL had a number of changes in name, but remained the operation providing research and developme ...

(SCL). Here, William R. Blair

William Richards Blair (November 7, 1874 – September 2, 1962) was an American scientist and United States Army officer, who worked on the development of the radar from the 1930s onward. He led the U.S. Army's Signal Corps Laboratories during its ...

had projects underway in detecting aircraft from thermal radiation

Thermal radiation is electromagnetic radiation generated by the thermal motion of particles in matter. Thermal radiation is generated when heat from the movement of charges in the material (electrons and protons in common forms of matter) i ...

and sound ranging, and started a project in Doppler-beat detection. Following Page's success with pulse-transmission, the SCL soon followed in this area. In 1936, Paul E. Watson developed a pulsed system that on December 14 detected aircraft flying in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

airspace at ranges up to seven miles. By 1938, this had evolved into the Army's first Radio Position Finding (RPF) set, designated ''SCR-268'', Signal Corps Radio

Signal Corps Radios were U.S. Army military communications components that comprised "sets". Under the Army Nomenclature System, the abbreviation SCR initially designated "Set, Complete Radio", but was later misinterpreted as "Signal Corps Radio."

...

, to disguise the technology. It operated at 200 MHz 1.5 m, with 7-kW peak power. The received signal was used to direct a searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

.

In Europe, the war with Germany had depleted the United Kingdom of resources. It was decided to give the UK's technical advances to the United States in exchange for access to related American secrets and manufacturing capabilities. In September 1940, the Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

began.

When the exchange began, the British were surprised to learn of the development of the U.S. Navy's pulse radar system, the CXAM, which was found to be very similar in capability to their Chain Home

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the of ...

technology. Although the U.S. had developed pulsed radar independently of the British, there were serious weaknesses in America's efforts, especially the lack of integration of radar into a unified air defense system. Here, the British were without peer.

The result of the Tizard Mission was a major step forward in the evolution of radar in the United States. Although both the NRL and SCL had experimented with 10–cm transmitters, they were stymied by insufficient transmitter power. The cavity magnetron was the answer the U.S. was looking for, and it led to the creation of the MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

Radiation Laboratory (Rad Lab). Before the end of 1940, the Rad Lab was started at MIT, and subsequently almost all radar development in the U.S. was in centimeter-wavelength systems. MIT employed almost 4,000 people at its peak during World War II.

Two other organisations were notable. As the Rad Lab began operations at MIT, a companion group, called the Radio Research Laboratory (RRL), was established at nearby Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

. Headed by Frederick Terman

Frederick Emmons Terman (; June 7, 1900 – December 19, 1982) was an American professor and academic administrator. He was the dean of the school of engineering from 1944 to 1958 and provost from 1955 to 1965 at Stanford University. He is widel ...

, this concentrated on electronic countermeasure

An electronic countermeasure (ECM) is an electrical or electronic device designed to trick or deceive radar, sonar, or other detection systems, like infrared (IR) or lasers. It may be used both offensively and defensively to deny targeting info ...

s to radar. Another organization was the Combined Research Group (CRG) housed at the NRL. This involved American, British, and Canadian teams charged with developing Identification Friend or Foe

Identification, friend or foe (IFF) is an identification system designed for command and control. It uses a transponder that listens for an ''interrogation'' signal and then sends a ''response'' that identifies the broadcaster. IFF systems usua ...

(IFF) systems used with radars, vital in preventing friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

accidents.

Metric-Wavelength

After trials, the original ''XAF'' was improved and designated '' CXAM''; these 200-MHz (1.5-m), 15-kW sets went into limited production with first deliveries in May 1940. The ''CXAM'' was refined into the ''SK'' early-warning radar, with deliveries starting in late 1941. This 200-MHz (1.5-m) system used a "flying bedspring" antenna and had a PPI. With 200-kW peak-power output, it could detect aircraft at ranges up to 100 miles, and ships at 30 miles. The ''SK'' remained the standard early-warning radar for large U.S. vessels throughout the war. Derivatives for smaller vessels were ''SA'' and ''SC''. About 500 sets of all versions were built. The related ''SD'' was a 114-MHz (2.63-m) set designed by the NRL for use on submarines; with a periscope-like antenna mount, it gave early warning but no directional information. The BTL developed a 500-MHz (0.6-m) fire-control radar designated ''FA'' (later, ''Mark 1''). A few went into service in mid-1940, but with only 2-kW power, they were soon replaced. Even before the '' SCR-268'' went into service, Harold Zahl was working at the SCL in developing a better system. The ''SCR-270

The SCR-270 (Set Complete Radio model 270) was one of the first operational early-warning radars. It was the U.S. Army's primary long-distance radar throughout World War II and was deployed around the world. It is also known as the Pearl Harbor ...

'' was the mobile version, and the ''SCR-271'' a fixed version. Operating at 106 MHz (2.83 m) with 100 kW pulsed power, these had a range up to 240 miles and began service entry in late 1940. On December 7, 1941, an ''SCR-270'' at Oahu

Oahu () ( Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over two-thirds of the population of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The island of O ...

in Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

detected the Japanese attack formation at a range of 132 miles (212 km), but this crucial plot was misinterpreted due to a grossly inefficient reporting chain.

One other metric radar was developed by the SCL. After Pearl Harbor, there were concerns that a similar attack might destroy vital locks on the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

. A transmitter tube that delivered 240-kW pulsed power at 600 MHz (0.5 M) had been developed by Zahl. A team under John W. Marchetti

John William Marchetti (June 6, 1908 – March 28, 2003) was a radar pioneer who had an outstanding career combining government and industrial activities. He was born of immigrant parents in Boston, Massachusetts, and entered Columbia College an ...

incorporated this in an ''SCR-268'' suitable for picket ships

Picket may refer to:

* Snow picket, a climbing tool

* Picket fence, a type of fence

* Screw picket, a tethering device

* Picket line, to tether horses

*"Picket line" is also used in picketing, a form of protest

**See also: "Strikebreaker, Crossing ...

operating up to 100 miles offshore. The equipment was modified to become the ''AN/TPS-3'', a light-weight, portable, early-warning radar used at beachheads and captured airfields in the South Pacific. About 900 were produced.

A British ''ASV Mk II'' sample was provided by the Tizard Mission. This became the basis for ''ASE'', for use on patrol aircraft such as the Consolidated PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served wi ...

. This was America's first airborne radar

Airborne or Airborn may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Airborne'' (1962 film), a 1962 American film directed by James Landis

* ''Airborne'' (1993 film), a comedy–drama film

* ''Airborne'' (1998 film), an action film sta ...

to see action; about 7,000 were built. The NRL were working on a 515-MHz (58.3-cm) air-to-surface radar for the Grumman TBF Avenger

The Grumman TBF Avenger (designated TBM for aircraft manufactured by General Motors) is an American World War II-era torpedo bomber developed initially for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, and eventually used by several air and naval a ...

, a new torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

. Components of the ''ASE'' were incorporated, and it went into production as the ''ASB'' when the U.S. entered the war. This set was adopted by the newly formed Army Air Forces as the SCR-521. The last of the non-magnetron radars, over 26,000 were built.

A final "gift" of the Tizard Mission was the Variable Time (VT) Fuze. Alan Butement had conceived the idea for a proximity fuse while he was developing the Coastal Defence system in Great Britain during 1939, and his concept was part of the Tizard Mission. The National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

(NDRC), asked Merle Tuve

Merle Anthony Tuve (June 27, 1901 – May 20, 1982) was an American geophysicist who was the Chairman of the Office of Scientific Research and Development's Section T, which was created in August 1940. He was founding director of the Johns Hopkins ...

of the Carnegie Institution of Washington

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

to take the lead in realising the concept, that could increase the probability of kill Computer games, simulations, models, and operations research programs often require a mechanism to determine statistically how likely the engagement between a weapon and a target will result in a satisfactory outcome (i.e. "kill"), known as the prob ...

for shells. From this, the variable-time fuze emerged as an improvement for the fixed-time fuze. The device sensed when the shell neared the target – thus, the name variable-time was applied.

A VT fuze, screwed onto the head of a shell, radiated a CW signal in the 180–220 MHz range. As the shell neared its target, this was reflected at a Doppler shifted frequency by the target and beat with the original signal, the amplitude of which triggered detonation. The device demanded radical miniaturisation of components, and 112 companies and institutions were ultimately involved. In 1942, the project was transferred to the Applied Physics Laboratory

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL) is a not-for-profit university-affiliated research center (UARC) in Howard County, Maryland. It is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University and emplo ...

, formed by Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

. During the war, some 22 million VT fuses for several calibres of shell were manufactured.

Centimeter