Mercure (ballet) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Mercure'' (''Mercury'', or ''The Adventures of Mercury'') is a 1924

''Mercure'' (''Mercury'', or ''The Adventures of Mercury'') is a 1924

The Soirées de Paris was a short-lived attempt by Count Étienne de Beaumont (1883–1956) – socialite,

The Soirées de Paris was a short-lived attempt by Count Étienne de Beaumont (1883–1956) – socialite,  Conspicuously absent from the project was the fourth key member of the ''Parade'' team, Jean Cocteau. While Satie owed much of his postwar fame to Cocteau's promotional efforts on his behalf, he had never really gotten along with the man he described as "a charming maniac." The author's increasingly exaggerated claims for his role in ''Parades success were a particular source of annoyance for both Satie and Picasso. In early 1924, just before creative talks for the Beaumont ballet got underway, Satie accused Cocteau of corrupting the morals of his onetime musical protégés

Conspicuously absent from the project was the fourth key member of the ''Parade'' team, Jean Cocteau. While Satie owed much of his postwar fame to Cocteau's promotional efforts on his behalf, he had never really gotten along with the man he described as "a charming maniac." The author's increasingly exaggerated claims for his role in ''Parades success were a particular source of annoyance for both Satie and Picasso. In early 1924, just before creative talks for the Beaumont ballet got underway, Satie accused Cocteau of corrupting the morals of his onetime musical protégés

Picasso's commission for ''Mercure'' came at a turning point in his career. Although he commanded great respect among the avant-garde as the co-founder of

Picasso's commission for ''Mercure'' came at a turning point in his career. Although he commanded great respect among the avant-garde as the co-founder of

In early 1924, Satie was at the height of his postwar cachet. He had produced little since his orchestral dance suite '' La belle excentrique'' (1921), but his role as "precursor" to

In early 1924, Satie was at the height of his postwar cachet. He had produced little since his orchestral dance suite '' La belle excentrique'' (1921), but his role as "precursor" to

One of Beaumont's objectives for the Soirées de Paris was to provide a comeback vehicle for Massine, who had been experiencing career difficulties since his acrimonious split from Diaghilev in 1921. He was installed in an apartment at the Beaumont estate and given two large rooms for private rehearsal space. Many of the dancers he employed had previously worked for the Ballets Russes, including the Soirées' female star Lydia Lopokova.

One of Beaumont's objectives for the Soirées de Paris was to provide a comeback vehicle for Massine, who had been experiencing career difficulties since his acrimonious split from Diaghilev in 1921. He was installed in an apartment at the Beaumont estate and given two large rooms for private rehearsal space. Many of the dancers he employed had previously worked for the Ballets Russes, including the Soirées' female star Lydia Lopokova.

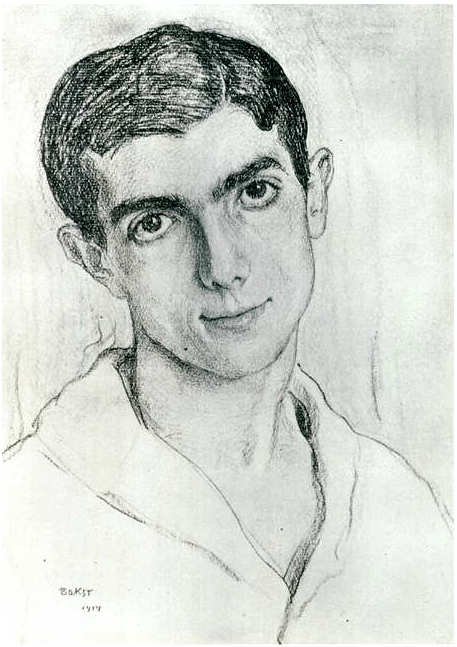

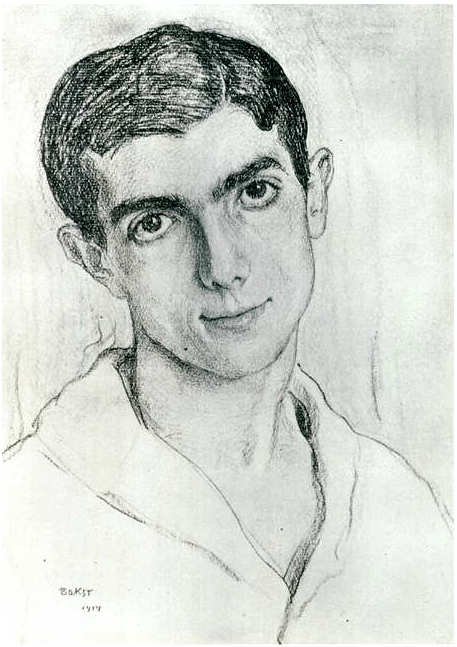

Massine had little to say about ''Mercure'' in later years, acknowledging that it was predominately Picasso's work. Surviving drawings reveal that Picasso designed actual groupings for the dancers – the "living pictures" demanded by Beaumont. Regarding the choreography, Massine noted, "As Mercury I had a series of adventures – intervening in the affairs of Apollo, directing the signs of the Zodiac, arranging the rape of Proserpine – each of which had to be clearly differentiated in order to strengthen the comic and dramatic content of the ballet." A review of a later production suggests that among the dancers he alone kept in constant motion: "Through this series of plastic poses flew Mercury, a vivid figure in white tunic and scarlet coat, enthusiastically danced by Massine."

Massine had little to say about ''Mercure'' in later years, acknowledging that it was predominately Picasso's work. Surviving drawings reveal that Picasso designed actual groupings for the dancers – the "living pictures" demanded by Beaumont. Regarding the choreography, Massine noted, "As Mercury I had a series of adventures – intervening in the affairs of Apollo, directing the signs of the Zodiac, arranging the rape of Proserpine – each of which had to be clearly differentiated in order to strengthen the comic and dramatic content of the ballet." A review of a later production suggests that among the dancers he alone kept in constant motion: "Through this series of plastic poses flew Mercury, a vivid figure in white tunic and scarlet coat, enthusiastically danced by Massine."

*Mercury

*

*Mercury

*

''Mercure'' premiered on June 15, 1924 in a hostile atmosphere due to Parisian cultural infighting of the time. The audience was studded with cliques for and against Picasso, Satie, and Beaumont, as well as supporters of Diaghilev, whose Ballets Russes were performing across town at the

''Mercure'' premiered on June 15, 1924 in a hostile atmosphere due to Parisian cultural infighting of the time. The audience was studded with cliques for and against Picasso, Satie, and Beaumont, as well as supporters of Diaghilev, whose Ballets Russes were performing across town at the

The Surrealists seized on this indifference to write a "Tribute to Picasso", published in the June 20 issue of ''Paris-Journal'' and subsequently reprinted in several periodicals:

:It is our duty to put on record our deep and wholehearted admiration for Picasso who goes on creating a troubling

The Surrealists seized on this indifference to write a "Tribute to Picasso", published in the June 20 issue of ''Paris-Journal'' and subsequently reprinted in several periodicals:

:It is our duty to put on record our deep and wholehearted admiration for Picasso who goes on creating a troubling

Diaghilev was disconcerted by the Soirées de Paris, not least because some of its artists were working for him at the same time. He called it "a soirée of the Ballets Russes in which the only thing missing is my name." But he attended its performances, and the originality of ''Mercure'' left him, according to Serge Lifar, "pale, agitated, nervous." In 1926, he took the unprecedented step of acquiring ''Mercure'' from Beaumont – the only time in his career that Diaghilev bought a ballet ready-made. The Ballets Russes presented it three times during its 1927 season: on June 2 at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt in Paris, and on July 11 and July 19 at the

Diaghilev was disconcerted by the Soirées de Paris, not least because some of its artists were working for him at the same time. He called it "a soirée of the Ballets Russes in which the only thing missing is my name." But he attended its performances, and the originality of ''Mercure'' left him, according to Serge Lifar, "pale, agitated, nervous." In 1926, he took the unprecedented step of acquiring ''Mercure'' from Beaumont – the only time in his career that Diaghilev bought a ballet ready-made. The Ballets Russes presented it three times during its 1927 season: on June 2 at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt in Paris, and on July 11 and July 19 at the  London's

London's

''Mercure'' (''Mercury'', or ''The Adventures of Mercury'') is a 1924

''Mercure'' (''Mercury'', or ''The Adventures of Mercury'') is a 1924 ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form ...

with music by Erik Satie

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie (, ; ; 17 May 18661 July 1925), who signed his name Erik Satie after 1884, was a French composer and pianist. He was the son of a French father and a British mother. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire, but was an und ...

. The original décor and costumes were designed by Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

and the choreography was by Léonide Massine

Leonid Fyodorovich Myasin (russian: Леони́д Фёдорович Мя́син), better known in the West by the French transliteration as Léonide Massine (15 March 1979), was a Russian choreographer and ballet dancer. Massine created the w ...

, who also danced the title role. Subtitled "Plastic Poses in Three Tableaux", it was an important link between Picasso's Neoclassical and Surrealist

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to ...

phases and has been described as a "painter's ballet."

''Mercure'' was commissioned by the Soirées de Paris stage company and first performed at the Théâtre de la Cigale in Paris on June 15, 1924. The conductor was Roger Désormière.Background

The Soirées de Paris was a short-lived attempt by Count Étienne de Beaumont (1883–1956) – socialite,

The Soirées de Paris was a short-lived attempt by Count Étienne de Beaumont (1883–1956) – socialite, balletomane

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

, and patron of the arts – to rival Serge Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, p ...

's Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. ...

as an arbiter of Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

in French theatre.John Richardson, ''A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932'', Alfred A. Knopf, 2010, pp. 256-262. Ornella Volta, "Satie Seen Through His Letters", Marion Boyars Publishers, New York, 1989, p. 168. He was famed for the extravagant annual costume balls he hosted at his Paris mansion and had enjoyed some success financing theatrical ventures, notably the Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (; 4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer, conductor, and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as ''The Group of Six''—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions ...

-Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the s ...

ballet '' Le boeuf sur le toit'' (1920). In late 1923, he rented the La Cigale

La Cigale (; English: ''The Cicada'') is a theatre located at 120, boulevard de Rochechouart near Place Pigalle, in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. The theatre is part of a complex connected to the Le Trabendo concert venue and the Boule Noi ...

music hall in Montmartre

Montmartre ( , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Right Bank. The historic district established by the City of Paris in 1995 is bordered by Rue Ca ...

, hired former Diaghilev associate Massine as his choreographer and commissioned an eclectic group of dance and dramatic pieces utilizing the talents of authors Cocteau and Tristan Tzara

Tristan Tzara (; ; born Samuel or Samy Rosenstock, also known as S. Samyro; – 25 December 1963) was a Romanian and French avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright, literary and art critic, comp ...

, composers Milhaud and Henri Sauguet

Henri-Pierre Sauguet-Poupard (18 May 1901 – 22 June 1989) was a French composer.

Born in Bordeaux, he adopted his mother's maiden name as part of his professional pseudonym. His output includes operas, ballets, four symphonies (1945, 1949 ...

, artists Georges Braque

Georges Braque ( , ; 13 May 1882 – 31 August 1963) was a major 20th-century French painter, collagist, draughtsman, printmaker and sculptor. His most notable contributions were in his alliance with Fauvism from 1905, and the role he play ...

, André Derain

André Derain (, ; 10 June 1880 – 8 September 1954) was a French artist, painter, sculptor and co-founder of Fauvism with Henri Matisse.

Biography

Early years

Derain was born in 1880 in Chatou, Yvelines, Île-de-France, just outside Paris. In ...

, and Marie Laurencin, and pioneer lighting designer Loie Fuller. Beaumont's biggest coup was reuniting Massine with Picasso and Satie for their first stage collaboration since the scandalous, revolutionary Diaghilev ballet ''Parade

A parade is a procession of people, usually organized along a street, often in costume, and often accompanied by marching bands, floats, or sometimes large balloons. Parades are held for a wide range of reasons, but are usually celebrations of s ...

'' (1917), and their work was anticipated as a highlight of the Soirées' inaugural season.

It was decided early on that ''Mercure'' would have no plot. The libretto has been variously attributed to Massine or Picasso, but the formal concept was Beaumont's. In a letter to Picasso dated February 21, 1924, Beaumont stated he wanted the ballet to be a series of ''tableaux vivants'' on a mythological theme, in a lighthearted manner suitable for a music hall. Beyond those stipulations he said, "I don't want to drag literature into it, nor do I want the composer or the choreographer to do so...do whatever you want." Satie's input appears to have been decisive in selecting the ancient Roman god Mercury as the subject – and not entirely for artistic reasons.

Conspicuously absent from the project was the fourth key member of the ''Parade'' team, Jean Cocteau. While Satie owed much of his postwar fame to Cocteau's promotional efforts on his behalf, he had never really gotten along with the man he described as "a charming maniac." The author's increasingly exaggerated claims for his role in ''Parades success were a particular source of annoyance for both Satie and Picasso. In early 1924, just before creative talks for the Beaumont ballet got underway, Satie accused Cocteau of corrupting the morals of his onetime musical protégés

Conspicuously absent from the project was the fourth key member of the ''Parade'' team, Jean Cocteau. While Satie owed much of his postwar fame to Cocteau's promotional efforts on his behalf, he had never really gotten along with the man he described as "a charming maniac." The author's increasingly exaggerated claims for his role in ''Parades success were a particular source of annoyance for both Satie and Picasso. In early 1924, just before creative talks for the Beaumont ballet got underway, Satie accused Cocteau of corrupting the morals of his onetime musical protégés Georges Auric

Georges Auric (; 15 February 1899 – 23 July 1983) was a French composer, born in Lodève, Hérault, France. He was considered one of ''Les Six'', a group of artists informally associated with Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. Before he turned 20 he ...

and Francis Poulenc

Francis Jean Marcel Poulenc (; 7 January 189930 January 1963) was a French composer and pianist. His compositions include mélodie, songs, solo piano works, chamber music, choral pieces, operas, ballets, and orchestral concert music. Among th ...

and severed ties with all three of them. He made the break public in an article for ''Paris-Journal'' (February 15, 1924), in which he castigated Cocteau and referred to recent ballets by Auric and Poulenc as "lots of syrupy things...buckets of musical lemonade." Auric used his position as music critic for ''Les Nouvelles littéraires

''Les Nouvelles littéraires'' was a French literary and artistic newspaper created in October 1922 by the Éditions Larousse. It disappeared in 1985 after having taken the title '.

History

''Les Nouvelles littéraires'' were headed by from 1922 ...

'' to retaliate and for several months he and Satie took potshots at each other in the French press. Their feud would come to a climax at the ''Mercure'' opening.

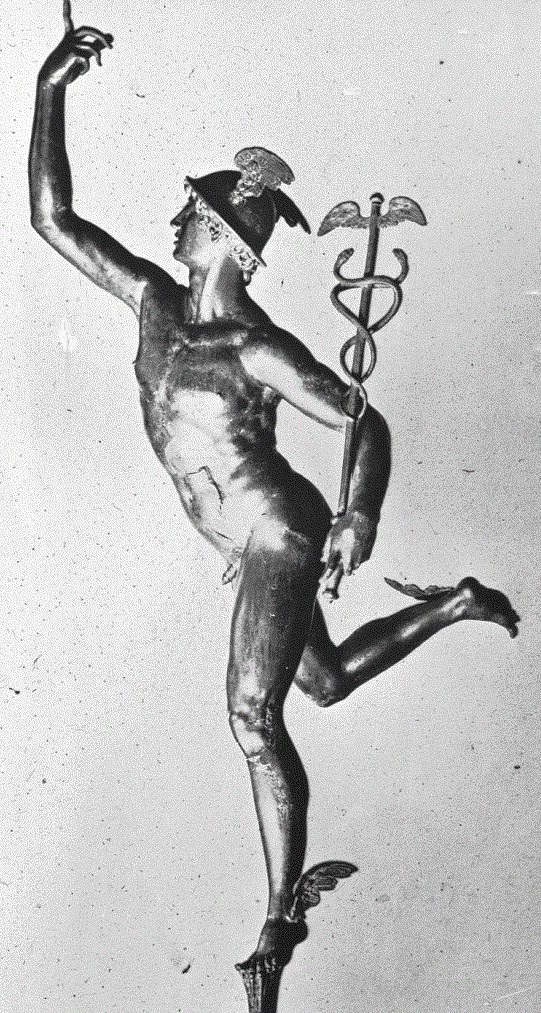

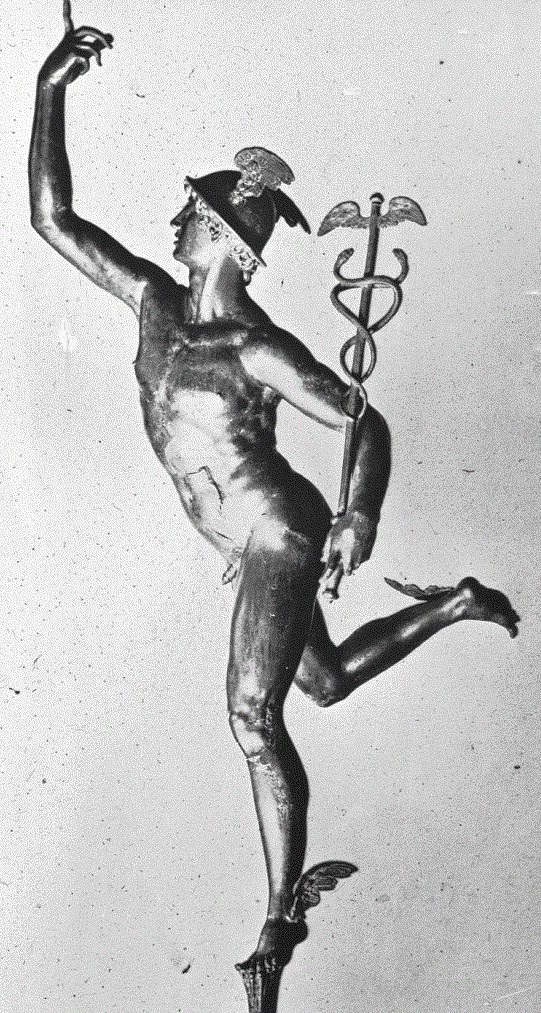

It was known among the Paris cognoscenti that Cocteau personally identified with Mercury and all that the figure stood for. He invariably attended costume balls (including Beaumont's) dressed as the deity, with silver tights, winged helmet and sandals, brandishing Mercury's wand as he darted among the other guests. Furthermore, he had cast himself as Mercutio

Mercutio ( , ) is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's 1597 tragedy, ''Romeo and Juliet''. He is a close friend to Romeo and a blood relative to Prince Escalus and Count Paris. As such, Mercutio is one of the named characters in the ...

in his upcoming adaptation of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

'' for the Soirées. Since the ballet was supposed to be a mythological spoof, Satie and Picasso saw in Mercury an opportunity for some veiled mockery at Cocteau's expense. In the final scenario, Mercury is presented as a meddlesome schemer who bounds onto the stage to cause trouble and chew the scenery. The in-jokes did not stop there: according to Belgian music critic Paul Collaer, the risqué supporting characters of the Three Graces – to be performed by men in drag with enormous fake breasts – were intended to represent Auric, Poulenc, and an arch-enemy of Satie's, the critic Louis Laloy. The creators kept their work secret and Satie jokingly told the inquisitive he had no clue what the ballet was about.

''Mise-en-scène''

Picasso's commission for ''Mercure'' came at a turning point in his career. Although he commanded great respect among the avant-garde as the co-founder of

Picasso's commission for ''Mercure'' came at a turning point in his career. Although he commanded great respect among the avant-garde as the co-founder of Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassemble ...

, his postwar Neoclassical paintings had made him prosperous and fashionable. He had abandoned Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. Montparnasse has bee ...

bohemianism for Right Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water. Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography, as follows.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terrai ...

high society, and there were grumblings among younger artists (especially the Dada

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 1920 Dada flourished in Pari ...

ists) that he had "sold out to the establishment."FitzGerald, "Making Modernism", p. 140. (His friend Max Jacob referred to this time as Picasso's "duchess period"). Now he was prepared to reassert his modernist credentials by creating a freer semi-abstract style, and chose this ballet as a suitably high-profile occasion in which to introduce it to the public.

The drop curtain he designed featured patches of muted color (earth tones and pastel shades of blue, white and red) suggesting forms and landscape, over which the figures of a guitar-playing Harlequin

Harlequin (; it, Arlecchino ; lmo, Arlechin, Bergamasque pronunciation ) is the best-known of the '' zanni'' or comic servant characters from the Italian '' commedia dell'arte'', associated with the city of Bergamo. The role is traditional ...

and Pierrot

Pierrot ( , , ) is a stock character of pantomime and '' commedia dell'arte'', whose origins are in the late seventeenth-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne. The name is a diminutive of ''Pi ...

with a violin were sinuously outlined in black. A lyre

The lyre () is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it ...

, the invention of Mercury, lies at their feet. A dimensional effect was created through dissociation of line and color. These principles were carried over into the largely monochrome

A monochrome or monochromatic image, object or palette is composed of one color (or values of one color). Images using only shades of grey are called grayscale (typically digital) or black-and-white (typically analog). In physics, monochr ...

backdrops and scenic constructions. Reliefs

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

of painted rattan

Rattan, also spelled ratan, is the name for roughly 600 species of Old World climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae. The greatest diversity of rattan palm species and genera are in the closed- canopy old-growth tropical fores ...

and wire were mounted onto large wooden cutouts with moveable parts, which hidden dancers shifted about the stage and manipulated along with the music. Some of them took the place of characters. The three-headed Cerberus

In Greek mythology, Cerberus (; grc-gre, Κέρβερος ''Kérberos'' ), often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld to prevent the dead from leaving. He was the offspring of the ...

was depicted on a circular shield beneath which only the dancer's feet were visible, and Massine described how the Three Graces were transformed into amorphous flats "with plaited necks like telephone extension wires which stretched and contracted as their heads bobbed up and down."Lynn Garafola, "Astonish Me!: Diaghilev, Massine and the Experimentalist Tradition", published in Mark Carroll (ed.), ''The Ballets Russes in Australia and Beyond'', Wakefield Press, 2011, pp. 52-74. André Breton

André Robert Breton (; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first '' Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') ...

called these puppet-like objects "tragic toys for adults." In counterpoint to the static poses of Massine's choreography, Picasso's mobile scenery became part of the dance.

After seeing the ballet Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

wrote, "The scenery of ''Mercure''... was written, quite simply written. There was no painting, it was pure calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

". Roland Penrose

Sir Roland Algernon Penrose (14 October 1900 – 23 April 1984) was an English artist, historian and poet. He was a major promoter and collector of modern art and an associate of the surrealists in the United Kingdom. During the Second World ...

elaborated on this, tracing Picasso's inspiration beyond Cubism to his early gifts for contour drawing: "From childhood... Picasso had enjoyed accomplishing the feat of drawing a figure or an animal with one continuous line. His ability to make a line twist itself into the illusion of a solid being, without taking pen from paper, had become an amazing act of virtuosity and a delight to watch. The costume drawings for ''Mercure'' are a masterly example of this kind of calligraphic drawing. With characteristic inventiveness, he had foreseen how they could be carried out on the stage... The results in terms of form and movement achieved with such simple means was a triumph."

Music

In early 1924, Satie was at the height of his postwar cachet. He had produced little since his orchestral dance suite '' La belle excentrique'' (1921), but his role as "precursor" to

In early 1924, Satie was at the height of his postwar cachet. He had produced little since his orchestral dance suite '' La belle excentrique'' (1921), but his role as "precursor" to Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most infl ...

and Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

was acknowledged, as was his advocacy of young French composers (Les Six

"Les Six" () is a name given to a group of six composers, five of them French and one Swiss, who lived and worked in Montparnasse. The name, inspired by Mily Balakirev's '' The Five'', originates in two 1920 articles by critic Henri Collet in ' ...

and the "Arcueil School"). The March 1924 edition of ''La Revue musicale

''La Revue musicale'' was a music magazine founded by Henry Prunières in 1920. ''La Revue musicale'' of Prunières was undoubtedly the first music publishing magazine giving as much attention to the quality of editing, iconography, and illustra ...

'' contained several laudatory articles about him, and that same month, he traveled to Belgium to give lectures on his music in Brussels and Antwerp. Beaumont trusted him implicitly and his influence pervaded the Soirées de Paris: most of its leading artists were Satie's friends or disciples, including 25-year-old music director Désormière, whose first important engagement this was. Once ''Mercure'' was finished, Satie would immediately tackle another big commission from Rolf de Maré

Rolf de Maré (9 May 1888 – 28 April 1964), sometimes called Rolf de Mare, was a Swedish art collector and leader of the Ballets Suédois in Paris in 1920–25. In 1931 he founded the world's first research center and museum for dance in Paris ...

of the Ballets suédois

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

; this resulted in his final compositions, the ballet '' Relâche'' and the score for its accompanying "cinematographic interlude", ''Entr'acte

(or ', ;Since 1932–35 the French Academy recommends this spelling, with no apostrophe, so historical, ceremonial and traditional uses (such as the 1924 René Clair film title) are still spelled ''Entr'acte''. German: ' and ', Italian: ''in ...

''.

A love of calligraphy was not the only thing Satie shared with Picasso. He was a perceptive, lifelong enthusiast of avant-garde art, from Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passa ...

to Dada. His friend Man Ray

Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealism, Surrealist movements, although his t ...

famously described him as "the only musician who had eyes." During the creation of ''Parade'' in 1916, he found Picasso's ideas most inspiring and Cocteau was forced to change his original scenario accordingly. On ''Mercure'', Satie was able to work with the artist directly and used only the design sketches as his guide. In an interview shortly before the premiere, Satie described his aesthetic approach: "You can imagine the marvelous contribution of Picasso, which I have attempted to translate musically. My aim has been to make the music an integral part, so to speak, with the actions and gestures of the people who move about in this simple exercise. You can see poses like them in any fairground. The spectacle is related quite simply to the music hall, without stylization, or any rapport with things artistic."

Satie evoked a music hall spirit by employing naïve-sounding themes (though their harmonies are not) and popular forms (march

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March ...

, waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

, polka

Polka is a dance and genre of dance music originating in nineteenth-century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. Though associated with Czech culture, polka is popular throughout Europe and the Americas.

History

Etymology

The te ...

), and in the occasional self-consciously "humorous" scoring. The melody of ''Signes du Zodiaque'' is given to the tuba, while the comic effect of the transvestite ''Bain des graces'' (''Bath of The Graces'') is heightened by being delicately scored for strings only. At the same time, the music steers clear of any direct narrative or illustrative impulses. Constant Lambert

Leonard Constant Lambert (23 August 190521 August 1951) was a British composer, conductor, and author. He was the founder and music director of the Royal Ballet, and (alongside Ninette de Valois and Frederick Ashton) he was a major figure in th ...

believed the best example of ''Mercures abstract quality was the penultimate number ''Le chaos'', "a skillful blending of two previously heard movements, one the suave and sustained ''Nouvelle danse'', the other the robust and snappy ''Polka des lettres''. These two tunes are so disparate in mood that the effect, mentally speaking, is one of complete chaos; yet it is achieved by strictly musical and even academic means which consolidate the formal cohesion of the ballet as a whole."Constant Lambert, ''Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline'', New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934 (first US edition), p. 130.

The harmonious collaboration Satie enjoyed with Picasso was not shared with Massine. ''Mercure'' was originally planned as a work lasting eight minutes, but the score grew to nearly twice that length.Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 232. With two other substantial ballets (Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (; 4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer, conductor, and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as ''The Group of Six''—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions ...

's ''Salade'' and the Strauss adaptation ''Le Beau Danube'') and several short ''divertissements'' to stage for the Soirées, Massine urged Satie to finish the music as quickly as possible. The fact that Satie borrowed an unpublished composition from his Schola Cantorum

The Schola Cantorum de Paris is a private conservatory in Paris. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Bordes, Alexandre Guilmant and Vincent d'Indy as a counterbalance to the Paris Conservatoire's emphasis on opera.

History

La Schola was founded ...

days, the ''Fugue-Valse'' (c. 1906), for the ''Danse de tendresse'' in Tableau I suggests he was indeed rushed by Massine. The composer finally wrote to him on April 7, "I can't possibly go any faster, mon cher Ami: I can't hand over to you work which I couldn't defend. You who are conscience personified will understand me." The piano score was completed on April 17 and the orchestration on May 9. Afterwards, Satie never forgave Massine for what he felt was the choreographer's attempt to compromise his work.

Satie did not provide musical interludes to cover the scenery changes between the three ''tableaux''. At the premiere, Désormière apparently repeated material from the ballet for this purpose, creating what Satie called "false intermissions." He demanded that the conductor follow the "original version" of the score so audiences would not misinterpret it, leaving the scene changes to take place in silence.

''Mercure'' is scored for an orchestra of modest proportions: 1 piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the s ...

, 1 flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedles ...

, 1 oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

, 2 clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitch ...

s in B, 1 bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuos ...

, 2 horns in F, 2 trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s in C, 1 trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrate ...

, 1 tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th century, making it one of the ne ...

, percussion for 2 players (snare drum

The snare (or side drum) is a percussion instrument that produces a sharp staccato sound when the head is struck with a drum stick, due to the use of a series of stiff wires held under tension against the lower skin. Snare drums are often used ...

, cymbal

A cymbal is a common percussion instrument. Often used in pairs, cymbals consist of thin, normally round plates of various alloys. The majority of cymbals are of indefinite pitch, although small disc-shaped cymbals based on ancient designs soun ...

s, bass drum

The bass drum is a large drum that produces a note of low definite or indefinite pitch. The instrument is typically cylindrical, with the drum's diameter much greater than the drum's depth, with a struck head at both ends of the cylinder. Th ...

), and strings.

Choreography

One of Beaumont's objectives for the Soirées de Paris was to provide a comeback vehicle for Massine, who had been experiencing career difficulties since his acrimonious split from Diaghilev in 1921. He was installed in an apartment at the Beaumont estate and given two large rooms for private rehearsal space. Many of the dancers he employed had previously worked for the Ballets Russes, including the Soirées' female star Lydia Lopokova.

One of Beaumont's objectives for the Soirées de Paris was to provide a comeback vehicle for Massine, who had been experiencing career difficulties since his acrimonious split from Diaghilev in 1921. He was installed in an apartment at the Beaumont estate and given two large rooms for private rehearsal space. Many of the dancers he employed had previously worked for the Ballets Russes, including the Soirées' female star Lydia Lopokova.

The Ballet

Satie called ''Mercure'' "a purely decorative spectacle." The episodes and characters were loosely drawn from Roman and Greek mythology, except for the figures of Polichinelle (from Italian ''Commedia dell'arte

(; ; ) was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. It was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is also known as , , and . Charact ...

'') and the Philosopher in Tableau III. Below is a list of the ballet's roles and musical numbers, and summaries of the stage action.

In the original production the ''Overture'', a light, jaunty march, was played beneath Picasso's curtain before the ballet proper began. With the exception of the ''Danse de tendresse'', each number lasts no more than a minute.

Roles

*Mercury

*

*Mercury

*Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

*Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

*Signs of the Zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The path ...

(''performed by 4 female dancers'')

*The Three Graces (''performed by 3 male dancers in drag'')

*Cerberus

*Philosopher

*Polichinelle

*Guest of Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

* Chaos (''performed by 5 male dancers'')

*Proserpine

Tableau I

*''Ouverture'' (''Overture'') *''La nuit'' (''Night'') *''Danse de tendresse'' (''Dance of Tenderness'') *''Signes du Zodiaque'' (''Signs of the Zodiac'') *''Entrée et danse de Mercure'' (''Entrance and Dance of Mercury'') Synopsis Night. Apollo and Venus make love, while Mercury surrounds them with the Signs of the Zodiac. Mercury becomes jealous of Apollo, kills him by cutting his thread of life, then revives him.Tableau II

*''Danse des grâces'' (''Dance of The Graces'') *''Bain des grâces'' (''Bath of The Graces'') *''Fuite de Mercure'' (''Flight of Mercury'') *''Colère de Cerbère'' (''The Fury of Cerberus'') Synopsis The Three Graces perform a dance, then remove their pearls to bathe. Mercury steals the pearls and flees, pursued by Cerberus.Tableau III

*''Polka des lettres'' (''Alphabet Polka'') *''Nouvelle danse'' (''New Dance'') *''Le chaos'' (''Chaos'') *''Rapt de Proserpine'' (''Rape of Proserpine'') Synopsis During a feast of Bacchus, Mercury invents the alphabet. AtPluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

's behest, he arranges for Chaos to abduct Proserpine. They carry her off on a chariot in the finale.

Premiere

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées () is an entertainment venue standing at 15 avenue Montaigne in Paris. It is situated near Avenue des Champs-Élysées, from which it takes its name. Its eponymous main hall may seat up to 1,905 people, while ...

. Most troublesome was the fledgeling Surrealist

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to ...

group led by André Breton

André Robert Breton (; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first '' Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') ...

and Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon (, , 3 October 1897 – 24 December 1982) was a French poet who was one of the leading voices of the surrealist movement in France. He co-founded with André Breton and Philippe Soupault the surrealist review ''Littérature''. He ...

. Breton was eager to win Picasso over to his cause and ready to use violence to defend his honor. During a Dada

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 1920 Dada flourished in Pari ...

event the previous year (at which Satie was present), he responded to poet Pierre de Massot's verbal attack of Picasso by breaking Massot's arm with his walking stick

A walking stick or walking cane is a device used primarily to aid walking, provide postural stability or support, or assist in maintaining a good posture. Some designs also serve as a fashion accessory, or are used for self-defense.

Walking st ...

. He also had a personal score to settle with Satie, who had presided over Breton's 1922 mock-trial at the Closerie des Lilas restaurant for attempting to overthrow Tzara as leader of the Dadaists. Georges Auric

Georges Auric (; 15 February 1899 – 23 July 1983) was a French composer, born in Lodève, Hérault, France. He was considered one of ''Les Six'', a group of artists informally associated with Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. Before he turned 20 he ...

had become friendly with the Surrealists and exploited Breton's enmity to pressure them into disrupting the performance of ''Mercure''.Richardson, "A Life of Picasso", p. 259.

The ballet had scarcely begun when the Surrealists started chanting "Bravo Picasso! Down with Satie!" from the back of the theatre. Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (; 4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer, conductor, and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as ''The Group of Six''—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions ...

argued with the Breton group, Satie fans voiced their support, and a handful of people approached Picasso's box and hurled insults at him. By Tableau II, there was pandemonium in the hall and the curtain had to be lowered. Lydia Lopokova witnessed the events from the audience and quoted a protester proclaiming "Only Picasso lives, down with Beaumont's garçons and the whole Soirées de Paris!" When police arrived to eject the demonstrators, Surrealist Francis Gérard reproached Picasso: "You see, Beaumont has the police throw us out because we were applauding you!" Louis Aragon, still raging against Satie, managed to jump onto the stage and shout, "In the name of God, down with the cops!" before he was dragged off. Order was finally restored and the ballet allowed to continue.

The Surrealists not taken into custody waited outside the venue, evidently hoping to see Picasso after the performance. Instead, they encountered Satie on his way out. The composer later reassured Milhaud, "They didn't say a word to me."

Five more performances of ''Mercure'' through June 22 passed without incident.

Reception

''Mercure'' was coolly received by the public and mainstream press. Maurice Boucher of ''Le Monde musical'' remarked that despite the opening night demonstration, there was little to get upset about. He dismissed Satie's music as "the ordinary pom-pom of the music hall" and attributed the minimalism of Picasso's décor to poverty of imagination – and, perhaps, a little drunkenness.Banes, "Writing Dancing in the Age of Postmodernism", Chapter 8.modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the "Age of Reas ...

at the highest level of expression. Once again, in ''Mercure'', he has shown a full measure of his daring and his genius, and has met with a total lack of understanding. This event proves that Picasso, ''far more than any of those around him'', is today the eternal personification of youth and the absolute master of the situation.

It was signed by Breton and 14 other artists and writers, including Aragon, Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealis ...

, and Philippe Soupault

Philippe Soupault (2 August 1897 – 12 March 1990) was a French writer and poet, novelist, critic, and political activist. He was active in Dadaism and later was instrumental in founding the Surrealist movement with André Breton. Soupault ini ...

. Renegade Dadaist Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia (: born Francis-Marie Martinez de Picabia; 22January 1879 – 30November 1953) was a French avant-garde painter, poet and typographist. After experimenting with Impressionism and Pointillism, Picabia became associated with Cubism ...

ridiculed this homage with a quip comparing Picasso's "troubling modernity" to the outdated fashions of designer Paul Poiret

Paul Poiret (20 April 1879 – 30 April 1944, Paris, France) was a French fashion designer, a master couturier during the first two decades of the 20th century. He was the founder of his namesake haute couture house.

Early life and care ...

, causing Aragon to counter with his own statement: "I think that nothing stronger than this ballet has ever been presented in the theatre. It is the revelation of an entirely new manner by Picasso, which owes nothing to cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassemble ...

or realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

* Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a mov ...

and which surpasses cubism just as it does realism."FitzGerald, "Making Modernism", p. 141. The American journal ''The Little Review

''The Little Review'', an American literary magazine founded by Margaret Anderson in Chicago's historic Fine Arts Building, published literary and art work from 1914 to May 1929. With the help of Jane Heap and Ezra Pound, Anderson created a ma ...

'' agreed that Picasso was the star of the show: "In ''Mercure'' the musician and the choreographer served purely as accompaniment to the painter. They felt this, and with remarkable art they acquiesced to this hegemony." Debates over the significance of Picasso's décor continued for weeks, including illustrated coverage in the July 1, 1924 issue of ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Australia'', an Australian fashion magazine

** ''Vogue China'', ...

'', which gave it the imprimatur of the ''haut monde''.

In its attempt to distance Picasso from his collaborators, the Surrealist "Tribute" sparked false rumors that Satie had fallen out with him as he had with so many other friends, due to his hypersensitive personality. Satie addressed this in a June 21 letter to Wieland Mayr, editor of the literary review ''les feuilles libres'': "Believe me, there is no divergence of views between Picasso and me. It's all a 'gimmick' by my old friend, the famous writer Bretuchon reton(''who came to create a disturbance and attract attention by his shabby appearance and deplorable rudeness''). Yes."

Picasso kept publicly aloof from the fray, but the Surrealists had gotten his attention. He annotated and saved a copy of their "Tribute".

Aftermath

Novice impresario Beaumont was a poor organizer. Performances by the Soirées de Paris were marked by last-minute cancellations, abrupt changes of program, and on one night, a musicians' strike just as the curtain was about to go up. Reviews were mixed at best (with Massine getting most of the praise) and the enterprise lost money.Volta, "Satie Seen Through His Letters", p. 172. The season was scheduled to run through June 30, including performances of ''Mercure'' on June 26, 27 and 28, but after June 22, the Soirées abruptly ceased without notice. Beaumont left his idle company in limbo for days before finally disbanding it. On June 29, Satie reported this to Rolf de Maré: "The Cigale (Beaumont) has closed its doors...This poor Count – who is, after all, a good man – instead of compliments has only received insults and other nice things... That's life! Most consoling!" The Soirées de Paris was never revived, but its brief existence had a notable impact on the careers of several of those involved. Beaumont himself continued to dabble in ballet. He wrote the libretto and designed the décor for Massine's popular Offenbach adaptation ''Gaîté Parisienne

''Gaîté Parisienne'' (literally, "Parisian Gaiety") is a 1938 ballet choreographed by Léonide Massine (1896-1979) to music by Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) arranged and orchestrated many decades later by Manuel Rosenthal (1904-2003) in collabo ...

'' (1938).

''Mercure'' was Picasso's last major work for the theatre, bringing to a close a momentous period of involvement in the ballet world that had begun with ''Parade'' eight years earlier. Always aiming to reinvent himself as an artist, he was quick to recognize the potential benefits of associating with Breton and his colleagues. ''Mercure'' was the catalyst for this. According to Michael C. FitzGerald, "With Picasso's reputation in danger of losing its avant-garde edge, the Surrealists' intervention publicly restored Picasso to his accustomed position. During the following decade, Surrealism would be a primary inspiration for his art and the principal context for its public reception."

The Soirées did succeed in re-launching Massine in Paris. He was soon reconciled with Diaghilev and welcomed back to the Ballets Russes as a "guest choreographer" in January 1925, remaining with them through 1928. Diaghilev also hired Désormière as principal conductor for his troupe's final years (1925-1929).

Cocteau was deeply offended by ''Mercure'', though he was careful to maintain his friendship with Picasso. In 1925, he wrote his play ''Orphée'', updating the title character into a famous but beleaguered Parisian poet. From then on, the figure of Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

replaced Mercury in his personal mythos.

Satie fared the worst in this undertaking. Poet and critic Rene Chalupt reported that even some of the composer's closest friends were disappointed by his music. ''Mercure'' set in motion a critical backlash against Satie that would reach fever pitch with the premiere of the Dadaist ''Relâche'' in December 1924, and was hardly quelled by his death eight months later. The irreverence and perceived flippancy of these last two ballets galvanized his enemies and disillusioned many supporters who had championed him as a serious composer, with long-term negative effects on his posthumous reputation.

Revivals

Diaghilev was disconcerted by the Soirées de Paris, not least because some of its artists were working for him at the same time. He called it "a soirée of the Ballets Russes in which the only thing missing is my name." But he attended its performances, and the originality of ''Mercure'' left him, according to Serge Lifar, "pale, agitated, nervous." In 1926, he took the unprecedented step of acquiring ''Mercure'' from Beaumont – the only time in his career that Diaghilev bought a ballet ready-made. The Ballets Russes presented it three times during its 1927 season: on June 2 at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt in Paris, and on July 11 and July 19 at the

Diaghilev was disconcerted by the Soirées de Paris, not least because some of its artists were working for him at the same time. He called it "a soirée of the Ballets Russes in which the only thing missing is my name." But he attended its performances, and the originality of ''Mercure'' left him, according to Serge Lifar, "pale, agitated, nervous." In 1926, he took the unprecedented step of acquiring ''Mercure'' from Beaumont – the only time in his career that Diaghilev bought a ballet ready-made. The Ballets Russes presented it three times during its 1927 season: on June 2 at the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt in Paris, and on July 11 and July 19 at the Prince's Theatre

The Shaftesbury Theatre is a West End theatre, located on Shaftesbury Avenue, in the London Borough of Camden. Opened in 1911 as the New Prince's Theatre, it was the last theatre to be built in Shaftesbury Avenue.

History

The theatre was d ...

in London. Massine recreated his choreography and role as Mercury. Constant Lambert found it "extremely funny but oddly beautiful",Stephen Lloyd, ''Constant Lambert: Beyond the Rio Grande'', Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2014, pp. 161-162. opinions not shared by London critics. The ''Times'' reviewer thought Satie's music and Picasso's "ridiculous contraptions" were outmoded, while dance historian and critic Cyril Beaumont wrote, "The whole thing appeared incredibly stupid, vulgar, and pointless." It was never again staged in its original form.

By that time, Satie's score had already provided the basis for another ballet in the United States. Former Ballets Russes dancer Adolph Bolm

Adolph Rudolphovich Bolm (russian: Адольф Рудольфович Больм; September 25, 1884 – April 16, 1951) was a Russian-born American ballet dancer and choreographer, of German descent.

Biography

Bolm graduated from the Russi ...

and his Chicago Allied Arts company presented it in 1926 under the title ''Parnassus on Montmartre'', with a new text about Parisian art students at a masquerade. Ruth Page starred.

London's

London's Ballet Rambert

Rambert (known as Rambert Dance Company before 2014) is a leading British dance company. Formed at the start of the 20th century as a classical ballet company, it exerted a great deal of influence on the development of dance in the United Kingd ...

mounted a more faithful version at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith

The Lyric Theatre, also known as the Lyric Hammersmith, is a theatre on Lyric Square, off King Street, Hammersmith, London.

on June 22, 1931. Frederick Ashton

Sir Frederick William Mallandaine Ashton (17 September 190418 August 1988) was a British ballet dancer and choreographer. He also worked as a director and choreographer in opera, film and revue.

Determined to be a dancer despite the opposit ...

choreographed and danced Mercury, Tamara Karsavina

Tamara Platonovna Karsavina (russian: Тамара Платоновна Карсавина; 10 March 1885 – 26 May 1978) was a Russian prima ballerina, renowned for her beauty, who was a principal artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet and l ...

guest-starred as Venus, and William Chappell portrayed Apollo. Constant Lambert revived Ashton's production for the Camargo Society The Camargo Society was a London society which created and produced ballet between 1930 and 1933, giving opportunity to British musicians, choreographers, designers and dancers. Janet Leeper (1945). ''English Ballet'', King Penguin Its influence ...

at the Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy P ...

in London on June 27, 1932, with Walter Gore

Walter Gore (8 October 1910 – 16 April 1979) was a British ballet dancer, company director and choreographer.

Early life

Walter Gore was born in Waterside, East Ayrshire Scotland in 1910 into a theatrical family. From 1924, he studied a ...

and Alicia Markova

Dame Alicia Markova DBE (1 December 1910 – 2 December 2004) was a British ballerina and a choreographer, director and teacher of classical ballet. Most noted for her career with Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and touring internat ...

as Mercury and Venus (renamed Terpsichore). Lambert also conducted a radio broadcast of Satie's music for ''Mercure'' over the BBC on July 13, 1932, and wrote admiringly of it in his book ''Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline'' (1934).

An adaptation entitled ''The Home Life of The Gods'' was produced by the Littlefield Ballet Littlefield may refer to:

Jurisdictions in the United States

* Littlefield, Arizona

* Littlefield, Texas

Littlefield is a city in and the county seat of Lamb County, Texas, United States. Its population was 6,372 at the 2010 census. It is ...

in Philadelphia in December 1936. The choreography was by Lasar Galpern.

Since World War II, ''Mercure'' has existed primarily as a concert piece. Désormière kept it in his repertoire and there is a live recording (December 2, 1947) of him performing it with the Orchestre National de France

The Orchestre national de France (ONF; literal translation, ''National Orchestra of France'') is a French symphony orchestra based in Paris, founded in 1934. Placed under the administration of the French national radio (named Radio France sinc ...

. Lambert broadcast ''Mercure'' again with the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

on June 14, 1949, as part of a three-concert Satie series he conducted for the BBC Third Programme

The BBC Third Programme was a national radio station produced and broadcast from 1946 until 1967, when it was replaced by Radio 3. It first went on the air on 29 September 1946 and quickly became one of the leading cultural and intellectual f ...

. Apart from Satie's score (first published in 1930), all that survives of the original production are Picasso's drop curtain and a few design sketches and photographs. The curtain was restored in 1998 and is on display at the Musée National d'Art Moderne

The Musée National d'Art Moderne (; "National Museum of Modern Art") is the national museum for modern art of France. It is located in Paris and is housed in the Centre Pompidou in the 4th arrondissement of the city. In 2021 it ranked 10th in t ...

in Paris. A woven tapestry replica, authorized by the artist in the late 1960s, hangs in the lobby of the Exxon Building in Manhattan.

In 1980, composer Harrison Birtwistle

Sir Harrison Birtwistle (15 July 1934 – 18 April 2022) was an English composer of contemporary classical music best known for his operas, often based on mythological subjects. Among his many compositions, his better known works include '' T ...

published his own instrumental arrangement of ''Mercure'', echoing a long-held (and disputed) opinion that Satie lacked skill as an orchestrator.Robert Adlington, "The Music of Harrison Birtwistle", Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 174.

Recordings

''Mercure'' is the least known of Satie's three major ballets and has had comparatively few commercial recordings. Among them are renditions by conductors Maurice Abravanel (Vanguard, 1968),Pierre Dervaux

Pierre Dervaux (born 3 January 1917 in Juvisy-sur-Orge, France; died 20 February 1992 in Marseilles, France) was a French operatic conductor, composer, and pedagogue. At the Conservatoire de Paris, he studied counterpoint and harmony with Marcel ...

(EMI, 1972), Bernard Herrmann

Bernard Herrmann (born Maximillian Herman; June 29, 1911December 24, 1975) was an American composer and conductor best known for his work in composing for films. As a conductor, he championed the music of lesser-known composers. He is widely r ...

(Decca, 1973), Ronald Corp

Ronald Geoffrey Corp, (born 4 January 1951) is a composer, conductor and Anglican priest. He is founder and artistic director of the New London Orchestra (NLO) and the New London Children's Choir. Corp is musical director of the London Chorus ...

(Musical Heritage Society, 1993, reissued by Hyperion in 2004), and Jérôme Kaltenbach (Naxos, 1999).

Notes and references

External links

* {{Pablo Picasso Compositions by Erik Satie Ballets by Erik Satie Ballets designed by Pablo Picasso Ballets by Léonide Massine 20th-century classical music 1924 ballet premieres Music riots Music controversies Ballet controversies Art works that caused riots