Koch–Pasteur rivalry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The French

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880 Toussaint reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible. Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it. Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues. (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880 Toussaint reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible. Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it. Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues. (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)

In 1883, responding to a

In 1883, responding to a

"Louis Pasteur"

''History Learning Site'', 2000–2011, Web. (Even without vaccination, not everyone bitten by a rabid dog develops rabies.) After other apparently successful cases, donations poured in from across the globe, funding the establishment of the

"Pasteur Institutes USA: A turn-of-the-century phenomenon"

, ''Remembrance of Things Pasteur'', Accessed 5 Sep 2012 on Web. A number of American copycats appeared, however, starting with "Chicago Pasteur Institute" in 1890, and "New York Pasteur Institute" in 1891. In 1897 a "Pasteur Institute" opened in

"Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Global Health & Novel Intervention Strategies"

, Institute of Medicine of National Academies, Apr 2010.

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

(1822–1895) and German Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

(1843–1910) are the two greatest figures in medical microbiology

Medical microbiology, the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various ...

and in establishing acceptance of the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade h ...

(germ theory). In 1882, fueled by national rivalry and a language barrier, the tension between Pasteur and the younger Koch erupted into an acute conflict.

Pasteur had already discovered molecular chirality

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from ...

, investigated fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food ...

, refuted spontaneous generation, inspired Lister's introduction of antisepsis

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

to surgery, introduced pasteurization

Pasteurization or pasteurisation is a process of food preservation in which packaged and non-packaged foods (such as milk and fruit juices) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than , to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life.

The ...

to France's wine industry, answered the silkworm

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically imp ...

diseases blighting France's silkworm industry, attenuated a '' Pasteurella'' species of bacteria to develop vaccine to chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

(1879), and introduced anthrax vaccine (1881).

Koch had transformed bacteriology by introducing the technique of pure culture, whereby he established the microbial cause of the disease anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

(1876), had introduced both staining and solid culture plates to bacteriology (1881), had identified the microbial cause of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

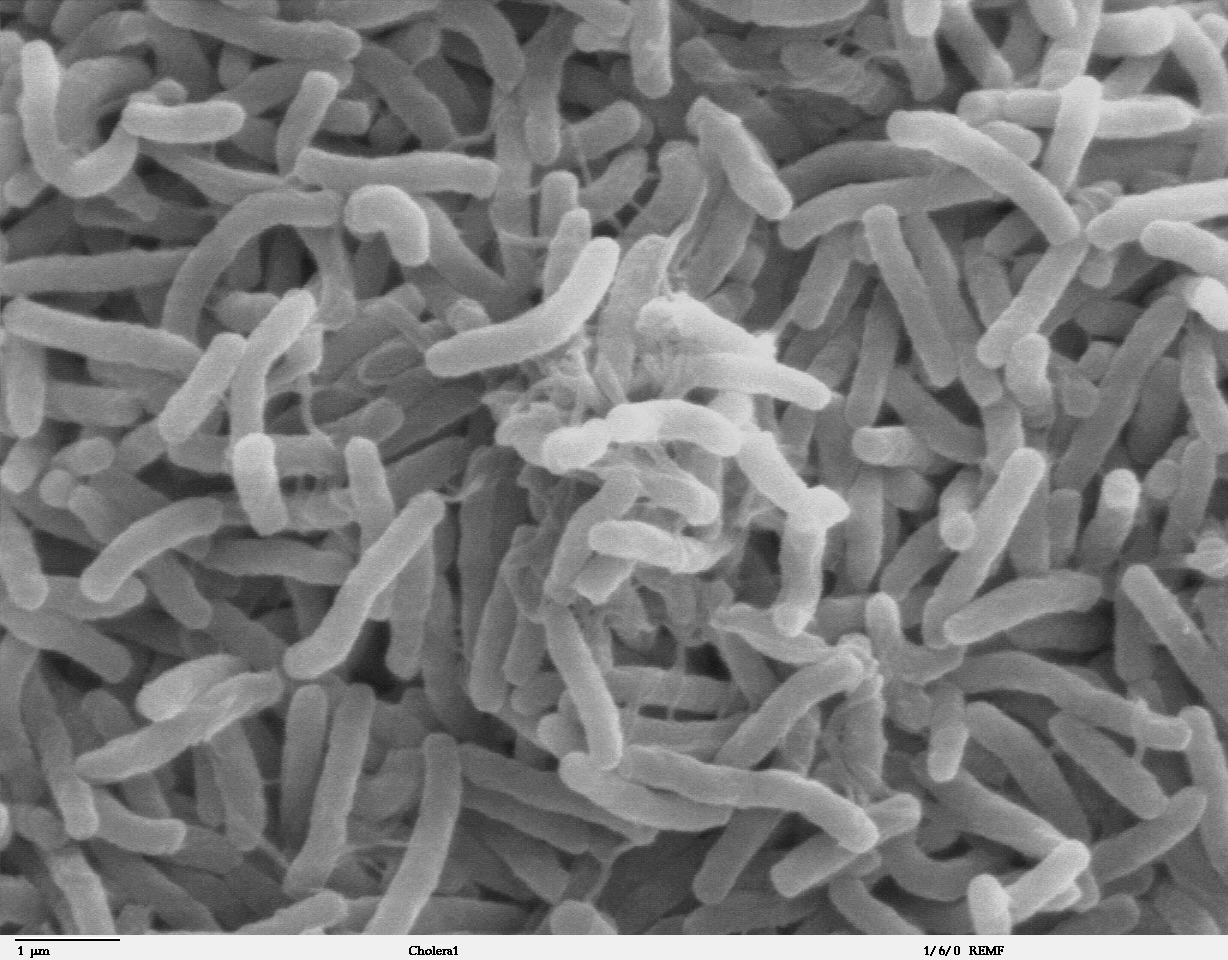

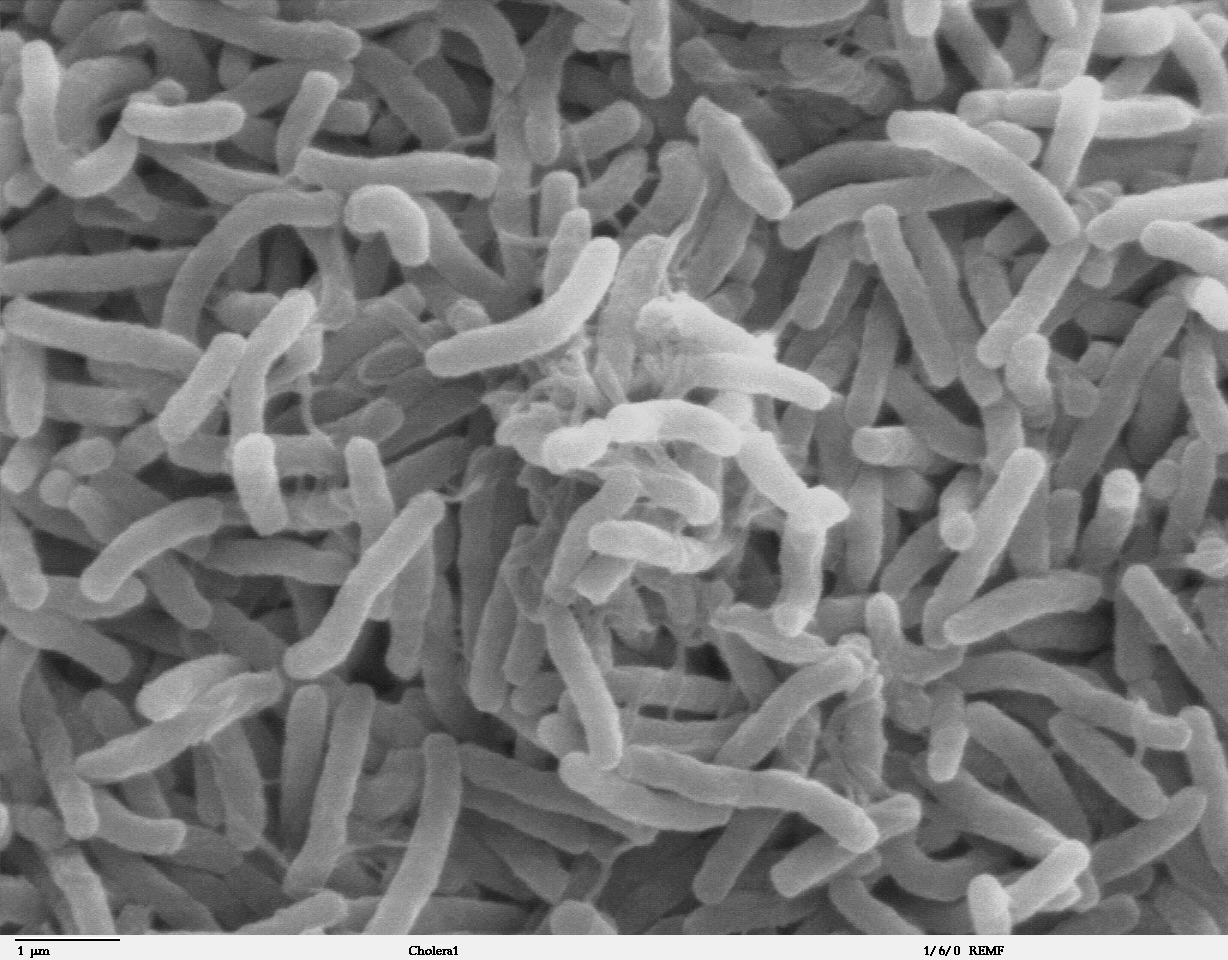

(1882), had incidentally popularized Koch's postulates for identifying the microbial cause of a disease, and would later identify the microbial cause of cholera (1883).

Although Koch had briefly and, thereafter, his bacteriological followers regarded a bacterial species' properties as unalterable, Pasteur's modification of virulence to develop vaccine demonstrated this doctrine's falsity. At an 1882 conference, a mistranslated term from French to German during Pasteur's lecture triggered Koch's indignation, whereupon Koch's two bacteriologist colleagues, Friedrich Loeffler and Georg Gaffky, published denigration of the entirety of Pasteur's research on anthrax since 1877.

Tensions between France and Germany

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (french: Université de Strasbourg, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, Alsace, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers.

The French university traces its history to the ea ...

, located in Alsace, where he married the daughter of the rector. Jean Baptiste Pasteur, the only son of Louis and Marie Pasteur, was a soldier in the Franco-Prussian War. The tone set by this war contributed to the rivalry between Koch and Pasteur. The "German Problem", as Germany increasingly gained scientific, technological, and industrial dominance, fed tensions among European nations. Germ theory's applications were embedded in the heightening quest by France, Germany, Britain, and Italy to colonize Africa and Asia with the aid of tropical medicine, a new variant of colonial medicine, while medical scientist

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practice ...

s in respective nations vied to lead advances.

Koch's bacteriology and anthrax

In 1863, influenced by Pasteur's research on fermentation, fellow Frenchman Casimir Davaine mostly explained the cause of anthrax, but Davaine's explanation was opposed by those who opposed the idea that infection with a microorganism could explain it. In 1840,Jakob Henle

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 – 13 May 1885) was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for ...

had proposed microorganism infections caused diseases, and in 1875 German botanist Ferdinand Cohn

Ferdinand Julius Cohn (24 January 1828 – 25 June 1898) was a German biologist. He is one of the founders of modern bacteriology and microbiology.

Ferdinand J. Cohn was born in the Jewish quarter of Breslau in the Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia ...

weighed in on a controversy in microbiology by declaring that the elementary unit was the cell and that each form of bacteria was constant and naturally divided from the other forms. Influenced by Henle and by Cohn, Koch developed a pure culture of the bacteria described by Davaine, traced its spore stage, inoculated it into animals, and showed it caused anthrax. Pasteur called this a "remarkable achievement". In pure culture, bacteria tend to keep constant traits, and Koch reported having already observed constancy.

Pasteur undertook investigation, yet gave much credit to Davaine. Meanwhile, Pasteur's researchers always reported variation in their cultures. In 1879, Henri Toussaint identified a bacterial species involved in chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

and named the genus in honor of Pasteur, '' Pasteurella''. In Pasteur's laboratory, a culture of '' Pasteurella multocida'' was left out over a weekend exposed to air, and Pasteur and Emile Roux

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*''Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*''Emil and the Detective ...

noticed upon return to the laboratory that its virulence to chickens was diminished. Pasteur applied the discovery to develop chicken cholera vaccine, introduced in a public experiment, an empirical challenge to the stance of Koch's bacteriologists that bacterial traits were unalterable.

Pasteur's attenuation and vaccines

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880 Toussaint reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible. Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it. Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues. (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880 Toussaint reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible. Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it. Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues. (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)

Microbe hunting, cholera, and public health

In 1883, responding to a

In 1883, responding to a cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt, both Pasteur and Koch sent missions vying to identify its cause. Koch returned victorious, whereupon Pasteur switched research direction and began development of rabies vaccine. As to public health, Koch's bacteriologists feuded with Max von Pettenkofer

Max Joseph Pettenkofer, ennobled in 1883 as Max Joseph von Pettenkofer (3 December 1818 – 10 February 1901) was a Bavarian chemist and hygienist. He is known for his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper s ...

—whose miasmatic theory claimed the bacteria was but one causal factor among at least several—but von Pettenkoffer stubbornly opposed water treatment, and the massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg, Germany, in 1892 devastated von Pettenkofer's position, and German public health was grounded on Koch's bacteriology. Meanwhile, Pasteur led introduction of pasteurization in France.

Rabies vaccine and Pasteur Institute

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

, uncommon but excruciating and almost invariably fatal, was dreaded. Amid anthrax vaccine's success, Pasteur introduced rabies vaccine (1885), the first human vaccine since Jenner's smallpox vaccine (1796). On 6 July 1885, the vaccine was tested on 9-year old Joseph Meister who had been bitten by a rabid dog but failed to develop rabies, and Pasteur was called a hero.Trueman C"Louis Pasteur"

''History Learning Site'', 2000–2011, Web. (Even without vaccination, not everyone bitten by a rabid dog develops rabies.) After other apparently successful cases, donations poured in from across the globe, funding the establishment of the

Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

in 1888.

Pasteur Institute trained military physicians in colonial medicine, although French government soon took over this role. The success of Pasteur's modification of bacterial virulence inspired confidence in the universality of Pasteurian science, though Pasteur's researchers preferred the term ''microbiology'' over the term ''bacteriology''. Koch discouraged use of rabies vaccine, whose production later became a premise for opening Pasteur Institutes abroad, as in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. The first overseas Pasteur Institute was opened by Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuated for ...

in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

in French Indochina in 1891, although Pasteur's nephew Adrien Loir

Adrien Loir (15 December 1862 – 1941) was a French bacteriologist born in Lyon. He was a nephew of Louis Pasteur, and for much of his career was associated with the Pasteur Institute.

From 1882 to 1888 Loir was an assistant in Pasteur's labo ...

was already planning to open one in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

.

Tuberculin and Robert Koch Institute

In 1882, Koch reported identification of the ''tubercle bacillus

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

'' as the cause of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, cementing germ theory. Koch took his research into a new direction—applied research

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge obtained via conclusions from the method to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted ...

—to develop a tuberculosis treatment and use the profits to found his own research institute, autonomous from government. In 1890 Koch introduced the intended drug, tuberculin, but it soon proved ineffective, and accounts of deaths followed in new press. Amid Koch's reluctance to disclose tuberculin's formula, Koch's reputation sustained damage, but Koch retained lasting acclaim and received the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis". Koch accepted government's offer to direct the Institute for Infectious Diseases (1891), in Berlin, a prestigious position but not the kind of institute that Koch had sought. It was later renamed the Robert Koch Institute

The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) is a German federal government agency and research institute responsible for disease control and prevention. It is located in Berlin and Wernigerode. As an upper federal agency, it is subordinate to the Federal ...

, which remains a government organization.

American medicine embraces Koch

The monomorphist doctrine of Koch's bacteriologists suggested public health interventions to eliminate bacteria, whereas Pasteur's acceptance of variation suggested attenuating bacterial virulence in the laboratory to develop vaccines. Although inspired by Pasteur's applications suggesting medicine's potential, American physicians traveled to Germany to learn Koch's bacteriology as basic science, though Pasteur emphasized the fuzzy boundary between basic science andapplied science

Applied science is the use of the scientific method and knowledge obtained via conclusions from the method to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted ...

.

From 1876 to 1878, the American William Henry Welch

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

trained in Germany pathology, and in 1879 opened America's first scientific laboratory, a pathology laboratory in Bellevue's medical school in New York. While in Germany, Welch had met John Shaw Billings

John Shaw Billings (April 12, 1838 – March 11, 1913) was an American librarian, building designer, and surgeon. However, he is best known as the modernizer of the Library of the Surgeon General's Office of the Army. His work with Andrew Carn ...

who had been appointed by Daniel Coit Gilman—the first president of the newly forming Johns Hopkins University—to plan Hopkins' hospital and medical school. Named the medical school's first dean in 1883, Welch promptly traveled for training in Koch's bacteriology, and returned to America eager to transform medicine with the "secrets of nature". Hopkins medical school opened in 1894 with Welch emphasizing Koch's bacteriology, which became the foundation of modern medicine.

As "dean of American medicine", William H Welch became the first scientific director of Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901), and appointed his former Hopkins student Simon Flexner the first director of pathology and bacteriology laboratories. Aided by the " Flexner report", published in 1910 while Welch was president of the American Medical Association, Welch's view of science and medicine became the national standard, a transformation of American medical education completed around 1930. As first dean of America's first public health school, founded in 1916 at Hopkins, Welch set the standard for public health, and with Simon Flexner exported the Hopkins model internationally.

Pasteur's image ascends

Although Pasteur died in 1895, eventually over thirty official Pasteur Institutes opened across the globe. Pasteur's team had planned in 1885 to open a rabies-treatment facility in St. Louis, Missouri, and an American Pasteur Institute in New York City, but the plans were abandoned, and America has never hosted an official Pasteur Institute.Pasteur Foundation"Pasteur Institutes USA: A turn-of-the-century phenomenon"

, ''Remembrance of Things Pasteur'', Accessed 5 Sep 2012 on Web. A number of American copycats appeared, however, starting with "Chicago Pasteur Institute" in 1890, and "New York Pasteur Institute" in 1891. In 1897 a "Pasteur Institute" opened in

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

, in 1900 in Pittsburgh and St. Louis, in 1903 in Ann Arbor

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), ...

and Austin

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the seat and largest city of Travis County, with portions extending into Hays and Williamson counties. Incorporated on December 27, 1839, it is the 11th-most-populous city ...

, and in 1904 perhaps in Philadelphia. In 1908, Georgia Department of Public Health opened a "Pasteur Department" in Atlanta, California State Hygienic Laboratory opened a "Pasteur Division" in Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, and a "Pasteur Institute" opened in Washington, D.C.

In 1900, Paul Gibier, the French medical scientist who opened "New York Pasteur Institute", accidentally died, but his nephew, George Gibier Rambaud, continued it on reduced scale until he closed it when US Medical Corps commissioned him overseas in 1918. While MDs ascended in American public health, it was thought that "the greatest contribution of all, the foundation upon which modern sanitary science is built, was made by Pasteur."

Nationalism flares

Koch was celebrated by the American medical community, including by Welch, when at last Koch visited America in 1908. Soon, however, America was influenced by the British and French view that although their denizens appreciated Germany's progress in science and arts, Germany was elitist and dismissive while socially and politically antiquated, so authoritarian and aggressive as to resemble medieval tyranny. In 1917, when America entered World War I (1914–18), US government seized German-owned property and assets, including Bayer AG's American trademarks and the 80% of Merck & Co's shares owned by George Merck. Welch exhibited gratuitous anti-German bias despite the debt of his own career, thus American medicine, to Germany, especially to Koch's bacteriology. After World War II (1939–45), and more of the "German Problem", Merck & Co became the global leader in vaccinology.Two legacies

Tuberculin's main use rapidly became in determining ''M tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

'' infection—a use remaining till today—but this use soon revealed that in London, 9 of 10 individuals were infected, whereas only 1 in 10 of the infected developed the disease. In 1901 at the London Congress on Tuberculosis, Koch stated on theoretical grounds that '' M bovis'', which infects cows, was not transmissible to humans. British attendees disagreed, and later Theobald Smith and the English Royal Commission empirically established that ''M bovis'' was transmissible and could result in human disease. Though widely considered ineffective as treatment, tuberculin might have remained in use for this purpose until the 1940s and maybe had some effectiveness.

Milk pasteurization

Pasteurization or pasteurisation is a process of food preservation in which packaged and non-packaged foods (such as milk and fruit juices) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than , to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life.

The ...

became popular in America around 1920. In 1921 Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuated for ...

and Camille Guérin

Jean-Marie Camille Guérin (; 22 December 1872 – 9 June 1961) was a French veterinarian, bacteriologist and immunologist who, together with Albert Calmette, developed the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), a vaccine for immunization against tuber ...

of Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

introduced tuberculosis vaccine

Tuberculosis (TB) vaccines are vaccinations intended for the prevention of tuberculosis. Immunotherapy as a defence against TB was first proposed in 1890 by Robert Koch.Prabowo, S. et al. "Targeting multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) by ...

, whose virulence of strains varied in the late 1920s. BCG vaccine was not used in the public health of America, which virtually eliminated tuberculosis without it. BCG vaccine's effectiveness preventing tuberculosis remains uncertain, but appears to confer nonspecific survival gains, as perhaps by preventing leprosy, and is a cancer treatment.

Pasteur had highlighted a new threat—microorganisms benign to humans passing among and multiplying in nonhuman animals while gaining new virulence for humans—that is thought to loom and to have approximately materialized with AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual m ...

. Although Koch's postulates are often inapplicable, they remain heuristic, and the authority of "fulfilling Koch's postulates" is still invoked in medical science, though often in modified form, as in the identification of HIV-1 as the cause of AIDS or the identification of SARS coronavirus

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1; or Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for th ...

as the cause of SARS.

Germ theory's stance that the "germ" was the disease's ''necessary and sufficient cause''—the single factor both required and complete to result in the disease—proved false. Germ theory gradually evolved to include other factors, whereupon germ theory resembled miasmatic theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmatic theory) is an obsolete medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or the Black Death—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad ...

, which had had to recognize bacteria as a causal factor, and so the two competing explanations merged without true, decisive victor. Twentieth-century philosophy, inspired by revolutions in physics, establishment of molecular biology, and advances in epidemiology, revealed that any claim of a single causal factor both necessary (required) and sufficient (complete), ''the'' cause, is untenable. French-born microbiologist René Dubos, a biographer of Pasteur, discussed tuberculosis to illustrate disease's social causes and to illustrate the failure of germ theory, whose apparent successes were aided by improvements in nutrition and living conditions but sparked scientific research that brought a wealth of new understandings.Meeting summary"Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Global Health & Novel Intervention Strategies"

, Institute of Medicine of National Academies, Apr 2010.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Koch-Pasteur Rivalry Scientific rivalry Microbiology 19th century in science France–Germany relations Robert Koch