Klaipėda Revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Klaipėda Revolt took place in January 1923 in the

Influenced by the Polish proposals, the Allies took Klaipėda Region into account when signing the peace treaty with Germany. According to article 28 of the

Influenced by the Polish proposals, the Allies took Klaipėda Region into account when signing the peace treaty with Germany. According to article 28 of the

On November 3–4, 1922, a delegation of Prussian Lithuanians unsuccessfully pleaded the Lithuanian case to the Conference of Ambassadors. This failure became the impetus to organize the uprising. During a secret session on November 20, 1922, the Lithuanian government decided to organize the revolt. They recognized that the diplomatic efforts through the League of Nations or the Conference of Ambassadors were fruitless and economic measures to sway the inhabitants towards Lithuania were too expensive and ineffective in international diplomacy. General Silvestras Žukauskas claimed that the

On November 3–4, 1922, a delegation of Prussian Lithuanians unsuccessfully pleaded the Lithuanian case to the Conference of Ambassadors. This failure became the impetus to organize the uprising. During a secret session on November 20, 1922, the Lithuanian government decided to organize the revolt. They recognized that the diplomatic efforts through the League of Nations or the Conference of Ambassadors were fruitless and economic measures to sway the inhabitants towards Lithuania were too expensive and ineffective in international diplomacy. General Silvestras Žukauskas claimed that the

The local population was engaged in the political tug of war between Germany, Lithuania, and free city. Reunion with Germany was a political impossibility, but local Germans wished to preserve their political and cultural dominance in the region. While Prussian Lithuanians spoke the

The local population was engaged in the political tug of war between Germany, Lithuania, and free city. Reunion with Germany was a political impossibility, but local Germans wished to preserve their political and cultural dominance in the region. While Prussian Lithuanians spoke the

In late 1922, Lithuanian activists were sent to various towns and villages to deliver patriotic speeches and organize a number of pro-Lithuanian Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor. On December 18, 1922, the

In late 1922, Lithuanian activists were sent to various towns and villages to deliver patriotic speeches and organize a number of pro-Lithuanian Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor. On December 18, 1922, the

Galvanauskas enlisted the paramilitary

Galvanauskas enlisted the paramilitary

File:Soldiers of the Lithuanian Army riding horses in Klaipėda (Memel), 1923.jpg, Soldiers of the Lithuanian Army riding horses in Klaipėda, 1923

File:Lithuanian medal with a box dedicated to the Klaipėda Revolt, 1923.jpg, Lithuanian medal with a box dedicated to the Klaipėda Revolt, 1923

File:Jonas Budrys and Lithuanian Military officers in Klaipeda (1923).jpg, Uprising military commander Jonas Budrys, the High Commissioner, and the

1923 documentary film ''Klaipėda Revolt''

* ttp://www.ostdeutsches-forum.net/fr/Histoire/PDF/Memel-Rapport-1923-F.pdf March 1923 report to the Conference of Ambassadors

German translation

Full text of the Klaipėda Convention of May 1924

{{DEFAULTSORT:Klaipeda Revolt 1923 in Lithuania 20th-century rebellions 20th century in Klaipėda Baltic rebellions Conflicts in 1923 Former eastern territories of Germany January 1923 events Klaipėda Region Lithuanian irredentism Wars involving Lithuania

Klaipėda Region

The Klaipėda Region ( lt, Klaipėdos kraštas) or Memel Territory (german: Memelland or ''Memelgebiet'') was defined by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles in 1920 and refers to the northernmost part of the German province of East Prussia, when as ...

(also known as the Memel Territory or ). The region, located north of the Neman River

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ...

, was detached from East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

and became a mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also ...

of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. It was placed under provisional French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

administration until a more permanent solution could be worked out. Lithuania wanted to unite with the region (part of Lithuania Minor

Lithuania Minor ( lt, Mažoji Lietuva; german: Kleinlitauen; pl, Litwa Mniejsza; russian: Ма́лая Литва́), or Prussian Lithuania ( lt, Prūsų Lietuva; german: Preußisch-Litauen, pl, Litwa Pruska), is a historical ethnographic re ...

) due to its large Lithuanian-speaking minority of Prussian Lithuanians and major port of Klaipėda (Memel) – the only viable access to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

for Lithuania. As the Conference of Ambassadors favored leaving the region as a free city, similar to the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

, the Lithuanians organized and staged a revolt.

Presented as an uprising of the local population, the revolt met little resistance from either the German police or the French troops. The rebels established a pro-Lithuanian administration, which petitioned to unite with Lithuania, citing the right of self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

. The League of Nations accepted the ''fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engli ...

'' and the Klaipėda Region was transferred as an autonomous territory to the Republic of Lithuania on February 17, 1923. After prolonged negotiations, a formal international agreement, the Klaipėda Convention

The Klaipėda Convention (or Convention concerning the Territory of Memel) was an international agreement between Lithuania and the countries of the Conference of Ambassadors (United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan) signed in Paris on May 8, 1 ...

, was signed in May 1924. The convention formally acknowledged Lithuania's sovereignty in the region and outlined its extensive legislative, judicial, administrative, and financial autonomy. The region remained part of Lithuania until March 1939 when it was transferred to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

after a German ultimatum.

Background

Lithuanian and Polish aspirations

The German–Lithuanian border had been stable since theTreaty of Melno

The Treaty of Melno ( lt, Melno taika; pl, Pokój melneński) or Treaty of Lake Melno (german: Friede von Melnosee) was a peace treaty ending the Gollub War. It was signed on 27 September 1422, between the Teutonic Knights and an alliance of the ...

in 1422. However, northern East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

had a significant Lithuanian-speaking population of Prussian Lithuanians or Lietuvninkai and was known as Lithuania Minor

Lithuania Minor ( lt, Mažoji Lietuva; german: Kleinlitauen; pl, Litwa Mniejsza; russian: Ма́лая Литва́), or Prussian Lithuania ( lt, Prūsų Lietuva; german: Preußisch-Litauen, pl, Litwa Pruska), is a historical ethnographic re ...

. The Klaipėda Region covered , which included the Curonian Lagoon of approximately . According to the Prussian Census of 1910, the city of Memel numbered 21,419 inhabitants, of whom 92% were German and 8% were Lithuanian, while the countryside was inhabited by a Lithuanian majority of 66%. In the Memel region as a whole, the Germans constituted 50.7% (71,191), the Lithuanians 47.9% (67,345), and the bilingual population (composed mostly of Lithuanians) – 1.4% (1,970). According to contemporary statistics by Fred Hermann Deu, 71,156 Germans and 67,259 Prussian Lithuanians lived in the region. The idea of uniting Lithuania Minor with Lithuania surfaced during the Lithuanian National Revival of the late 19th century. It was part of the vision to consolidate all ethnic Lithuanian lands into an independent Lithuania. The activists also eyed Klaipėda (Memel), a major sea port in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. It would become Lithuania's only deep-water access to the sea and having a port was seen as an economic necessity for self-sustainability. On November 30, 1918, twenty-four Prussian Lithuanian activists signed the Act of Tilsit, expressing their desire to unite Lithuania Minor with Lithuania. Based on these considerations, the Lithuanians petitioned the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

to attach the whole of Lithuania Minor (not limited to Klaipėda Region) to Lithuania. However, at the time Lithuania was not officially recognized by the western powers and not invited into any post-war conferences. Lithuania was recognized by the United States in July 1922 and by most western powers in December 1922.

The Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

regarded the Klaipėda Region as possible compensation for Danzig. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Polish Corridor provided access to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, but the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

was not granted to Poland. In early 1919, Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

, the Polish representative to the Paris Peace Conference, campaigned for the incorporation of Klaipėda Region into Lithuania, which was then to enter into a union with Poland (see Dmowski's Line and Międzymorze

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

federation). The Polish formula was Klaipėda to Lithuania, Lithuania to Poland. Until the Polish–Lithuanian union could be worked out, Klaipėda was to be placed under the temporary administration of the Allies. While such a union had a historic tradition in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, Lithuania categorically refused any such proposals. Worsening Polish–Lithuanian relations led to the Polish–Lithuanian War

The Polish–Lithuanian War (in Polish historiography, Polish–Lithuanian Conflict) was an undeclared war between newly-independent Lithuania and Poland following World War I, which happened mainly, but not only, in the Vilnius and Suwałki regi ...

and dispute over the Vilnius Region. However, the union idea was met favorably in Western Europe. In December 1921, Poland sent Marceli Szarota as a new envoy to the region. Due to his initiative, Poland and Klaipėda signed a trade agreement in April 1922. In addition, Poland attempted to establish its economic presence by buying property, establishing business enterprises, and making connections with the port.

French administration

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, effective January 10, 1920, lands north of the Neman River

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ...

were detached from the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and, according to article 99, were placed under a mandate of the League of Nations

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

. The French agreed to become temporary administrators of the region while the British declined. The first French troops, the of '' Chasseurs Alpins'' under General , arrived on February 10, 1920. The Germans officially handed over the region on February 15. Two days later General Odry established a seven-member Directorate

Directorate may refer to:

Contemporary

*Directorates of the Scottish Government

* Directorate-General, a type of specialised administrative body in the European Union

* Directorate-General for External Security, the French external intelligence ag ...

—the main governing institution. After Lithuanian protests, two Prussian Lithuanian representatives were admitted to the Directorate, increasing its size to nine members. On June 8, 1920, France appointed as the head of the civilian administration in the Klaipėda Region. Petisné showed anti-Lithuanian bias and was favorable towards the idea of a free city. General Odry resigned on May 1, 1920, leaving Petisné the highest-ranking official in the region.

French Prime Minister and chairman of the Paris Peace Conference Georges Clemenceau commented that the Klaipėda Region was not attached to Lithuania because it had not yet received ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' recognition. The Lithuanians seized this statement and further campaigned for their rights in the region believing that once they received international recognition, the region should be theirs. As the mediation of the Polish–Lithuanian conflict over the Vilnius Region by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

was going nowhere, the Klaipėda Region became a major bargaining chip. Already in 1921, implicit "Klaipėda-for-Vilnius" offers were made. In March 1922, the British made a concrete and explicit offer: in exchange for recognition of Polish claims to Vilnius, Lithuania would receive ''de jure'' recognition, Klaipėda Region, and economic aid. The Lithuanians rejected the proposal as they were not ready to give up on Vilnius. After the rejection, the French and British attitudes turned against Lithuania and they now favored the free city solution (''Freistadt'' like the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

). Thus the Lithuanians could wait for an unfavorable decision or they could seize the region and present a ''fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engli ...

''.

Preparations

Decision

On November 3–4, 1922, a delegation of Prussian Lithuanians unsuccessfully pleaded the Lithuanian case to the Conference of Ambassadors. This failure became the impetus to organize the uprising. During a secret session on November 20, 1922, the Lithuanian government decided to organize the revolt. They recognized that the diplomatic efforts through the League of Nations or the Conference of Ambassadors were fruitless and economic measures to sway the inhabitants towards Lithuania were too expensive and ineffective in international diplomacy. General Silvestras Žukauskas claimed that the

On November 3–4, 1922, a delegation of Prussian Lithuanians unsuccessfully pleaded the Lithuanian case to the Conference of Ambassadors. This failure became the impetus to organize the uprising. During a secret session on November 20, 1922, the Lithuanian government decided to organize the revolt. They recognized that the diplomatic efforts through the League of Nations or the Conference of Ambassadors were fruitless and economic measures to sway the inhabitants towards Lithuania were too expensive and ineffective in international diplomacy. General Silvestras Žukauskas claimed that the Lithuanian Army

The Lithuanian Armed Forces () are the military of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of the Lithuanian Land Forces, the Lithuanian Naval Force and the Lithuanian Air Force. In wartime, the Lithuanian State Border Guard Service (wh ...

could disarm the small French regiment and take the region in 24 hours. However, a direct military action against France was too dangerous, both in military and diplomatic sense. Therefore, it was decided to stage a local revolt, using the example of the Polish Żeligowski's Mutiny in October 1920.

The preparations were left in the hands of Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Ernestas Galvanauskas

Ernestas Galvanauskas (20 November 1882 – 24 July 1967) was a Lithuanian engineer, politician and one of the founders of the Peasant Union (which later merged with the Lithuanian Popular Peasants' Union). He also served twice as Prime Minis ...

. While he delegated specific tasks, the grand plan was kept secret even from the First Seimas

First Seimas of Lithuania was the first parliament (Seimas) democratically elected in Lithuania after it declared independence on February 16, 1918.

History

The elections took place on October 10–11, 1922 to replace the Constituent Assembl ...

or Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

and thus very few Lithuanians understood the full role of the government in the revolt. Thus the main credit for organization of the revolt is sometimes given to Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius

Vincas Mickevičius (pl. ''Wincenty Mickiewicz'', October 19, 1882 – July 17, 1954), better known by his pen name Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, was a Lithuanian writer, poet, novelist, playwright and philologist. He is also known as Vincas Krė ...

, Chairman of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union

The Lithuanian Riflemen's Union (LRU, lt, Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga), also referred to as Šauliai ( lt, šaulys for ''rifleman''), is a paramilitary non-profit organisation supported by the State. The activities are in three main areas: milita ...

, which provided the manpower. Galvanauskas planned to present the revolt as a genuine uprising of the local population against its German Directorate and not against the French or Allied administration. Such plan was designed to direct Allied protests away from the Lithuanian government and to exploit the anti-German sentiment in Europe. Galvanauskas was careful to hide any links between the rebels and the Lithuanian government so that if the revolt failed he could blame the Riflemen and the rebels absolving the government of any responsibility. Galvanauskas warned that all those involved could be subject to criminal persecutions if it was necessary for Lithuania's prestige.

Propaganda campaigns

The local population was engaged in the political tug of war between Germany, Lithuania, and free city. Reunion with Germany was a political impossibility, but local Germans wished to preserve their political and cultural dominance in the region. While Prussian Lithuanians spoke the

The local population was engaged in the political tug of war between Germany, Lithuania, and free city. Reunion with Germany was a political impossibility, but local Germans wished to preserve their political and cultural dominance in the region. While Prussian Lithuanians spoke the Lithuanian language

Lithuanian ( ) is an Eastern Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is the official language of Lithuania and one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.8 millio ...

, they had developed their own complex identity, including a different religion ( Lutherans as opposed to Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

Lithuanians). The Lithuanians were seen as both economically and culturally backward people. Farmers and industry workers worried that cheaper produce and labor from Lithuania would destroy their livelihood. Therefore, the idea of a free city was gaining momentum. At the end of 1921, Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den Freistaat Memel (Society for Free State Memel) collected 54,429 signatures out of 71,856 total eligible residents (75.7%) in support of the free state.

Therefore, even before the decision to organize the revolt, Lithuania attempted to maximize its influence and attract supporters in the region. Lithuania restricted its trade to demonstrate region's economic dependence as it did not produce enough food. The economic situation was further complicated by the beginning of hyperinflation of the German mark, which the region used as its currency. The Lithuanian cause was also supported by industrialists, who expected cheap labor and raw materials from Lithuania. Lithuanians also engaged in intense propaganda. They established and financed pro-Lithuanian organizations and acquired interest in local press. Many of these activities were coordinated by Lithuanian envoy Jonas Žilius, who received 500,000 German mark

The Deutsche Mark (; English: ''German mark''), abbreviated "DM" or "D-Mark" (), was the official currency of West Germany from 1948 until 1990 and later the unified Germany from 1990 until the adoption of the euro in 2002. In English, it was ...

s for such purposes. Banker Jonas Vailokaitis donated US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

12,500 () for the cause and pledged another $10,000 if needed. Additional support was provided by Lithuanian Americans

Lithuanian Americans refers to American citizens and residents who are Lithuanian and were born in Lithuania, or are of Lithuanian descent. New Philadelphia, Pennsylvania has the largest percentage of Lithuanian Americans (20.8%) in the United ...

, including Antanas Ivaškevičius (Ivas) and Andrius Martusevičius (Martus). For several weeks before the revolt, the local press reported on alleged Polish plans for the region. This was designed to strengthen the anti-Polish sentiment and paint Lithuania as a more favorable solution. It seems that these actions had the intended result and public opinion shifted towards Lithuania.

International diplomacy

Germany understood that the region would not be re-attached. Therefore, they favored the lesser of two evils and tacitly supported the interests of Lithuania. TheWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

saw both Poland and France as its major enemies while Lithuania was more neutral. Also, once Germany restored its might, it would be much easier to recapture the region from weaker Lithuania than from larger Poland. Already on February 22, 1922, the Germans unofficially informed the Lithuanians that they were not opposed to Lithuanian action in Klaipėda and that, understandably, such a stance would never be officially declared. Such attitudes were later confirmed in other unofficial German–Lithuanian communications and even during the revolt, when Berlin urged local Germans not to hinder the Lithuanian plans.

When the Allies contemplated turning Klaipėda into a free city like Danzig, Polish Foreign Minister Konstanty Skirmunt believed that such a free city would hurt the Polish interest by allowing Germany to maintain its influence in the region. Skirmunt instead supported the transfer of the region to Lithuania if Poland would secure unrestricted trade via the Neman River and the port. At the same time Poland was preoccupied by other issues (assassination of President Gabriel Narutowicz, economic crisis, territorial disputes in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

, tense relations with Soviet Russia) and paid less attention to Klaipėda. Lithuania understood that a military action against Polish interest in the region could resume the Polish–Lithuanian War

The Polish–Lithuanian War (in Polish historiography, Polish–Lithuanian Conflict) was an undeclared war between newly-independent Lithuania and Poland following World War I, which happened mainly, but not only, in the Vilnius and Suwałki regi ...

. To counter the expected backlash from Poland and France, the Lithuanians looked for an ally in Soviet Russia, which opposed a strong Polish state. On November 29, Soviet Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin stopped briefly in Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

on his way to Berlin. In a conversation with Galvanauskas, Chicherin expressed support for Lithuanian plans in Klaipėda and declared that Soviet Russia would not remain passive if Poland moved against Lithuania.

Timing

On December 18, 1922, a committee of the Conference of Ambassadors scheduled the presentation of a proposal for the future of the region on January 10, 1923. While the content of the proposal was not known until after the start of the revolt, the Lithuanians expected the decision to be against their interest and hastened their preparations. Indeed, the committee proposed either creating a free city (an autonomous region under the League of Nations) or transferring the region to Lithuania if it agreed to a union with Poland. January 1923 was also convenient as France was distracted by theoccupation of the Ruhr

The Occupation of the Ruhr (german: link=no, Ruhrbesetzung) was a period of military occupation of the Ruhr region of Germany by France and Belgium between 11 January 1923 and 25 August 1925.

France and Belgium occupied the heavily industria ...

and Europe feared the outbreak of another war. The domestic situation in Lithuania was also favorable: Galvanauskas, as the Prime Minister, had extensive powers while the First Seimas

First Seimas of Lithuania was the first parliament (Seimas) democratically elected in Lithuania after it declared independence on February 16, 1918.

History

The elections took place on October 10–11, 1922 to replace the Constituent Assembl ...

was deadlocked and the election of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Aleksandras Stulginskis, who strongly opposed the revolt, was contested.

Revolt

Political actions

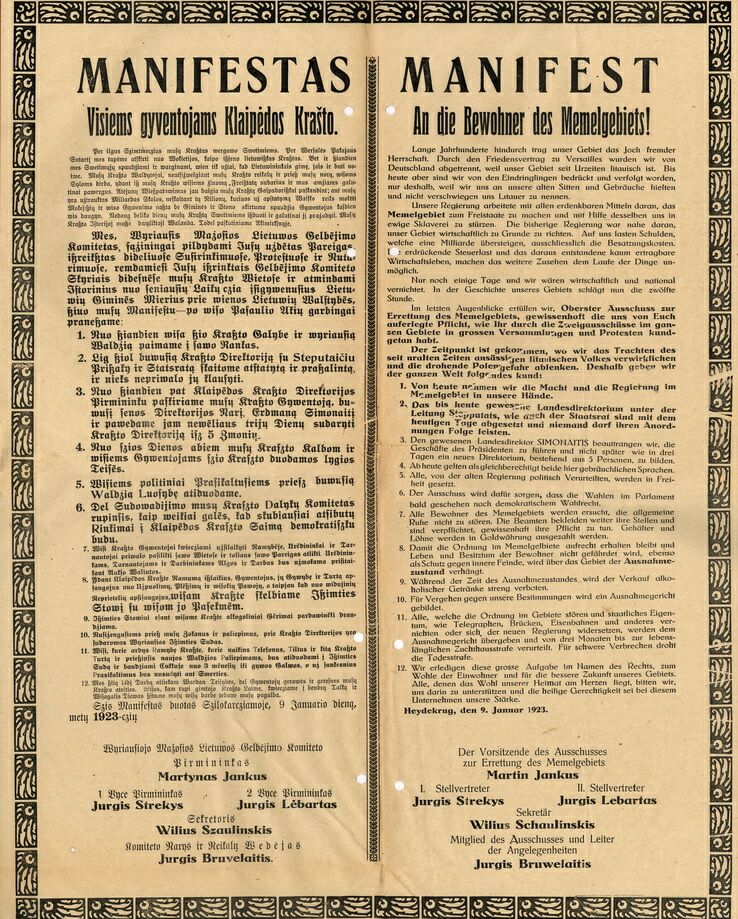

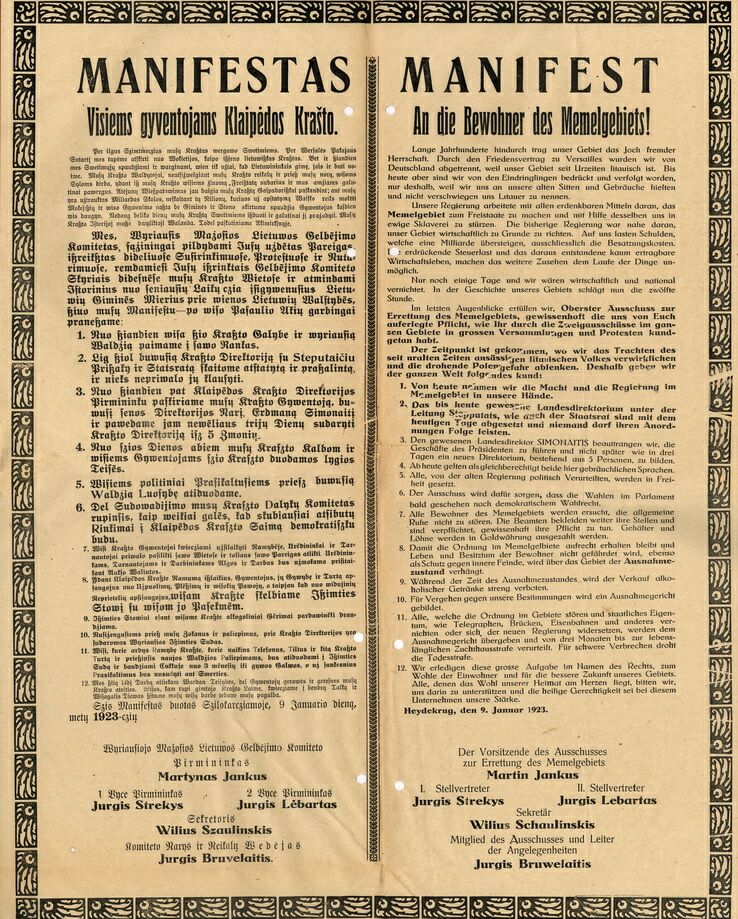

In late 1922, Lithuanian activists were sent to various towns and villages to deliver patriotic speeches and organize a number of pro-Lithuanian Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor. On December 18, 1922, the

In late 1922, Lithuanian activists were sent to various towns and villages to deliver patriotic speeches and organize a number of pro-Lithuanian Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor. On December 18, 1922, the Supreme Committee for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor

Supreme may refer to:

Entertainment

* Supreme (character), a comic book superhero

* ''Supreme'' (film), a 2016 Telugu film

* Supreme (producer), hip-hop record producer

* "Supreme" (song), a 2000 song by Robbie Williams

* The Supremes, Motown-e ...

(SCSLM), chaired by Martynas Jankus

Martynas Jankus or Martin Jankus (7 August 1858 in Bittehnen (Lit.: Bitėnai), near Ragnit – 23 May 1946 in Flensburg, Germany, reburied in Bitėnai cemetery on 30 May 1993) was a Prussian-Lithuanian printer, social activist and publisher in ...

, was established in Klaipėda to unite all these committees. It was to lead the revolt and later organize a pro-Lithuanian regime in the region. According to Jankus testimony to the Conference of Ambassadors in March 1923, up to 8,000–10,000 persons (5–7% of the population) were united around the Committee before January 10, 1923. On January 3, 1923, a congress of the committees authorized SCSLM to represent the interest of the inhabitants of the entire region. However, at the time the organization was just a name and apart from issuing several declarations had no other activity. Some of its members admitted that they learned about their role in the SCSLM only after the revolt. On January 7, the SCSLM published a proclamation, ''Broliai Šauliai!'', alleging that the Lithuanians were persecuted by foreigners, declaring its resolve to take up arms to rid itself of "slavery", and pleading the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union

The Lithuanian Riflemen's Union (LRU, lt, Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga), also referred to as Šauliai ( lt, šaulys for ''rifleman''), is a paramilitary non-profit organisation supported by the State. The activities are in three main areas: milita ...

for help. This became the official pretext for the riflemen to enter into the region on January 9.

On January 9, the SCSLM declared that, based on the authorization from other salvation committees to represent all inhabitants of the region, the SCSLM usurped all power in the region, dissolved the Directorate

Directorate may refer to:

Contemporary

*Directorates of the Scottish Government

* Directorate-General, a type of specialised administrative body in the European Union

* Directorate-General for External Security, the French external intelligence ag ...

, chaired by Vilius Steputaitis (Wilhelm Stepputat), and authorized Erdmonas Simonaitis

Erdmonas Simonaitis (October 30, 1888, in Juschka-Spötzen ( Spiečiai), Province of East Prussia, German Empire – February 24, 1969, in Weinheim, West Germany) was a Prussian Lithuanian activist particularly active in the Klaipėda Region (Memel ...

to form a new five-member Directorate within 3 days. The declaration also provided that the German and Lithuanian language

Lithuanian ( ) is an Eastern Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is the official language of Lithuania and one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.8 millio ...

were given equal status as official languages of the region, all political prisoners were to be released, martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

was enacted. In addition to this declaration, the Committee issued a French appeal to the French soldiers, in which they, as "fighters for noble ideas of freedom and equality", were asked not to fight against the "will and achievements of the Lithuanian nation". On January 13, Simonaitis formed a new pro-Lithuanian Directorate, which included Vilius Gaigalaitis, Martynas Reizgys, Jonas Toleikis, and Kristupas Lekšas. On January 19, representatives of Committees for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor met in Šilutė

Šilutė (, previously ''Šilokarčiama'', german: link=no, Heydekrug), is a city in the south of the Klaipėda County, Lithuania. The city was part of the Klaipėda Region and ethnographic Lithuania Minor. Šilutė was the interwar capital of Š ...

(Heydekrug) and passed a five-point declaration, asking for the region to be incorporated as an autonomous district into Lithuania. The document was signed by some 120 people. The region's autonomy extended to local taxation, education, religion, court system, agriculture, social services. On January 24, the First Seimas

First Seimas of Lithuania was the first parliament (Seimas) democratically elected in Lithuania after it declared independence on February 16, 1918.

History

The elections took place on October 10–11, 1922 to replace the Constituent Assembl ...

(parliament of Lithuania) accepted the declaration thus formalizing the incorporation of the Klaipėda Region. Antanas Smetona

Antanas Smetona (; 10 August 1874 – 9 January 1944) was a Lithuanian intellectual and journalist and the first President of Lithuania from 1919 to 1920 and again from 1926 to 1940, before its occupation by the Soviet Union. He was one of the m ...

was sent as the chief envoy to the region.

Military actions

Galvanauskas enlisted the paramilitary

Galvanauskas enlisted the paramilitary Lithuanian Riflemen's Union

The Lithuanian Riflemen's Union (LRU, lt, Lietuvos šaulių sąjunga), also referred to as Šauliai ( lt, šaulys for ''rifleman''), is a paramilitary non-profit organisation supported by the State. The activities are in three main areas: milita ...

to provide manpower for the revolt. Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius

Vincas Mickevičius (pl. ''Wincenty Mickiewicz'', October 19, 1882 – July 17, 1954), better known by his pen name Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, was a Lithuanian writer, poet, novelist, playwright and philologist. He is also known as Vincas Krė ...

, chairman of the union, believed that the idea to organize the revolt originated within the organization and Galvanauskas only tacitly approved the plan while carefully distancing the government from the rebels. In December 1922, Krėvė-Mickevičius met with Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

's commander Hans von Seeckt and was assured that German army would not interfere with the Lithuanian plans in the region. Krėvė-Mickevičius cheaply bought 1,500 guns, five light machine guns, and 1.5 million rounds of ammunition from the Germans. The military action was coordinated by Lithuanian counterintelligence officer and former Russian colonel Jonas Polovinskas, who changed his name to Jonas Budrys, which sounded more Prussian Lithuanian. Later his entire staff

Staff may refer to:

Pole

* Staff, a weapon used in stick-fighting

** Quarterstaff, a European pole weapon

* Staff of office, a pole that indicates a position

* Staff (railway signalling), a token authorizing a locomotive driver to use a particula ...

changed their last names to sound more Prussian Lithuanian. According to memoirs of Steponas Darius, the revolt was first scheduled for the night of the New Year, but the Lithuanian government pulled out based on a negative intelligence report. Supporters of the revolt gathered in Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Trakai ...

and convinced the government to proceed. The delay jeopardized the mission as the secret could have leaked to the Allies.

The revolt started on January 10, 1923. Arriving with trains to Kretinga and Tauragė

Tauragė (; see other names) is an industrial city in Lithuania, and the capital of Tauragė County. In 2020, its population was 21,520. Tauragė is situated on the Jūra River, close to the border with the Kaliningrad Oblast, and not far from th ...

, 1,090 volunteers (40 officers, 584 soldiers, 455 riflemen, three clerks, two doctors, six orderlies) crossed the border into the region. Among them were Steponas Darius and Vladas Putvinskis Vladas is a Lithuanian given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Vladas Česiūnas

*Vladas Drėma

*Vladas Mikėnas

*Vladas Mironas

*Vladas Petronaitis

*Vladas Tučkus

*Vladas Zajanckauskas

*Vladas Žulkus

See also

*Vlada

Vlada is a Sla ...

. They wore civilian clothes and had green armband with letters ''MLS'' for ''Mažosios Lietuvos sukilėlis'' or ''Mažosios Lietuvos savanoris'' (rebel/volunteer of Lithuania Minor). Each man had a rifle and 200 bullets; the rebels had a total of 21 light machine gun

A light machine gun (LMG) is a light-weight machine gun designed to be operated by a single infantryman, with or without an assistant, as an infantry support weapon. LMGs firing cartridges of the same caliber as the other riflemen of the sam ...

s, four motorcycles, three cars, 63 horses. In hopes of negotiating a peaceful retreat of the French and to avoid any casualties, shooting was allowed only as a last resort of self-defense. Galvanauskas ordered perfect behavior (politeness, no plunder, no alcoholic drinks, no political speeches) and no Lithuanian identification (no Lithuanian documents, money, tobacco, or matchboxes). In the Klaipėda Region, these men were met by some 300 local volunteers, though Lithuanian historian Vygandas Vareikis disputed the accuracy of this assertion. More local men joined once the rebels reached cities. The rebels met little resistance, but struggled with cold winter weather, lack of transportation and basic supplies (they were not provided with food or clothes, but were given a daily allowance of 4000 German marks).

The contingent was divided into three armed groups. The first and strongest group (530 men commanded by Major Jonas Išlinskas codename Aukštuolis) was ordered to take Klaipėda. The second group (443 men led by Captain Mykolas Kalmantavičius codename Bajoras) was sent to capture Pagėgiai

Pagėgiai (, german: Pogegen) is a city in south-western Lithuania. It is located in the medieval region of Scalovia in the historic region of Lithuania Minor. It is the capital of Pagėgiai municipality, and as such it is part of Tauragė Coun ...

(Pogegen) and secure the border with Germany and the third (103 men led by Major Petras Jakštas codename Kalvaitis) to Šilutė

Šilutė (, previously ''Šilokarčiama'', german: link=no, Heydekrug), is a city in the south of the Klaipėda County, Lithuania. The city was part of the Klaipėda Region and ethnographic Lithuania Minor. Šilutė was the interwar capital of Š ...

(Heydekrug). By January 11, the pro-Lithuanian forces controlled the region, except for the city of Klaipėda. The French administrator Pestiné refused to surrender and fighting over Klaipėda broke out on January 15. The city was defended by 250 French soldiers, 350 German policemen, and 300 civilian volunteers. After a brief gunfight, a ceasefire was signed by Pestiné and Budrys and the French soldiers were interned in their barracks. During the fighting, 12 insurgents, two French soldiers, and one German policeman were killed. According to German sources, one French soldier died and two were injured. On January 16, the Polish ship '' Komendant Piłsudski'' entered the port of Klaipėda carrying Colonel Eugène Trousson, a member of the French military mission in Poland, and reinforcements to French troops. However, the ship soon departed as the fighting was over and ceasefire was in effect. On January 17–18, the British cruiser HMS ''Caledon'' and two French torpedo boats, ''Algérien'' and ''Senégalais'', reached Klaipėda. The French cruiser ''Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

'' was on its way. The Lithuanians began organizing a local army, which included 317 men by January 24. The men were enticed by a guaranteed six-month position and a wage of two litas

The Lithuanian litas (ISO currency code LTL, symbolized as Lt; plural ''litai'' (nominative) or ''litų'' (genitive) was the currency of Lithuania, until 1 January 2015, when it was replaced by the euro. It was divided into 100 centų (genit ...

a day.

Reaction and aftermath

France protested against the Lithuanian actions and issued direct military threats demanding to return to the ''status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When used ...

''. Britain protested, but refrained from threats. It was suspected that Lithuania had Soviet support, which meant that if either France or Poland initiated a military response Soviet Russia would intervene, possibly causing another war. Poland protested, but also feared wider repercussions. It offered military assistance, but only if France and Britain approved. On January 17, 1923, the Conference of Ambassadors decided to dispatch a special commission, led by Frenchman Georges Clinchant. The commission with a handful of Allied troops arrived on January 26 and almost immediately demanded that the rebels withdraw from the region, threatening to use force, but quickly backed down. On January 29, the Allies rejected the proposal to send troops to quash the revolt. France wanted to restore its administration, but Britain and Italy supported the transfer of the region to Lithuania. On February 2, the Allies presented a sternly worded ultimatum demanding withdrawal of all rebels from the region, disbandment of any armed forces, Steponaitis' Directorate and the Supreme Committee for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor.

At the same time, the League was making its final decision regarding the bitter territorial dispute over the Vilnius Region between Poland and Lithuania. On February 3, the League decided to divide the wide neutral zone, established in the aftermath of the Żeligowski's Mutiny in November 1920. Despite Lithuanian protests, the division of the neutral zone proceeded on February 15. In these circumstances, the League decided on an unofficial exchange: Lithuania would receive the Klaipėda Region for the lost Vilnius Region. By February 4, the Allied ultimatum was replaced by a diplomatic note requesting that the transfer of the Klaipėda Region would be orderly and not coerced. On February 11, the Allies even thanked Lithuania for the peaceful resolution of the crisis. To further appease the League, the Simonaitis' Directorate was disbanded on February 15. Viktoras Gailius formed a provisional five-member Directorate, which included two Germans and three Prussian Lithuanians. On February 17, the Conference transferred the region to Lithuania under several conditions to be later formalized in the Klaipėda Convention

The Klaipėda Convention (or Convention concerning the Territory of Memel) was an international agreement between Lithuania and the countries of the Conference of Ambassadors (United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan) signed in Paris on May 8, 1 ...

: the region would be granted autonomy, Lithuania would compensate Allied costs of administration and assume German liabilities of war reparations, and the Neman River

The Neman, Nioman, Nemunas or MemelTo bankside nations of the present: Lithuanian: be, Нёман, , ; russian: Неман, ''Neman''; past: ger, Memel (where touching Prussia only, otherwise Nieman); lv, Nemuna; et, Neemen; pl, Niemen; ...

would be internationalized. Lithuania accepted and thus the revolt was legitimized. The French and British ships left the port on February 19.

Initially the proposed Klaipėda Convention reserved extensive rights for Poland to access, use, and govern the port of Klaipėda. This was completely unacceptable to Lithuania, which had terminated all diplomatic ties with Poland over the Vilnius Region. The stalled negotiations were referred to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. The three-member commission, chaired by American Norman Davis, prepared the final convention which was signed by Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and Lithuania in May 1924. The Klaipėda Region became an autonomous region under unconditional sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

of Lithuania. The region had extensive legislative, judicial, administrative, and financial autonomy and elected its own local parliament. The port of Klaipėda was internationalized allowing freedom of transit. The convention was hailed as a major Lithuanian diplomatic victory as it contained none of the special rights initially reserved for Poland and placed no conditions on Lithuanian sovereignty in the region. However, the convention severely limited the powers of the Lithuanian government and caused frequent debates on the relationship between central and local authorities. In the 1920s, the relations between Lithuania and Germany under Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann were rather normal. However, tensions began to rise after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power. Weaknesses of the convention were exploited by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

when it supported anti-Lithuanian activities and campaigned for reincorporation of the region into Germany. This culminated in a 1939 ultimatum, which successfully demanded that Lithuania give up the Klaipėda Region under threat of invasion.

Lithuanian Army

The Lithuanian Armed Forces () are the military of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of the Lithuanian Land Forces, the Lithuanian Naval Force and the Lithuanian Air Force. In wartime, the Lithuanian State Border Guard Service (wh ...

officers arrive in Klaipėda in 1923

References

Bibliography

* * * * * *Other languages

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

1923 documentary film ''Klaipėda Revolt''

* ttp://www.ostdeutsches-forum.net/fr/Histoire/PDF/Memel-Rapport-1923-F.pdf March 1923 report to the Conference of Ambassadors

German translation

Full text of the Klaipėda Convention of May 1924

{{DEFAULTSORT:Klaipeda Revolt 1923 in Lithuania 20th-century rebellions 20th century in Klaipėda Baltic rebellions Conflicts in 1923 Former eastern territories of Germany January 1923 events Klaipėda Region Lithuanian irredentism Wars involving Lithuania