History of vegetarianism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest records of

The earliest records of

Philosopher

Philosopher

The religions of

The religions of

In 675, the use of

In 675, the use of

It was during the

It was during the

During the

During the

In Russia,

In Russia,

''A Fleshless Diet: Vegetarianism as a Rational Dietary''

''American Physical Education Review'' 16: 352. Cranks opened in Carnaby Street, London, in 1961, as the first successful vegetarian restaurant in the UK. Eventually there were five Cranks restaurants in London which closed in 2001. The Indian concept of

Today,

Today,

The earliest records of

The earliest records of vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism may ...

as a concept and practice amongst a significant number of people are from ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

, especially among the Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

and Jains

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

.Spencer, Colin: ''The Heretic's Feast. A History of Vegetarianism'', London 1993 Later records indicate that small groups within the ancient Greek civilizations in southern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and Greece also adopted some dietary habits similar to vegetarianism. In both instances, the diet was closely connected with the idea of nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

toward animals (called ''ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

'' in India), and was promoted by religious groups and philosophers.

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire

The growth of Christianity from its obscure origin 40 AD, with fewer than 1,000 followers, to being the majority religion of the entire Roman Empire by AD 350, has been examined through a wide variety of historiographical approaches.

Unt ...

in late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

(4th–6th centuries), vegetarianism nearly disappeared from Europe. Several orders of monks

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedicat ...

in medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

restricted or banned the consumption of meat for ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

reasons but none of them abstained from the consumption of fish; these monks were not vegetarians but some were pescetarians. Vegetarianism was to reemerge somewhat in Europe during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

and became a more widespread practice during the 19th and 20th centuries. The figures for the percentage of the Western world which is vegetarian varies between 0.5% and 4% per Mintel data in September 2006.

Ancient

Indian subcontinent

Early Jainism and Buddhism

Jain and Buddhist sources show that the principle of nonviolence toward animals was an established rule in both religions as early as the 6th century BCE. The Jain concept, which is particularly strict, may be even older. Lord Parshvanath, the 23rd Jain leader whom modern historians consider to be a historical figure, lived in the 9th century BCE. He is said to have preached nonviolence no less strictly than it was practiced in theJain community

The Jains in India are the last direct representatives of the ancient Shramana tradition. People who practice Jainism, an ancient religion of the Indian subcontinent, are collectively referred to as Jains.

Sangha

Jainism has a fourfold orde ...

during the times of Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit: महावीर) also known as Vardhaman, was the 24th ''tirthankara'' (supreme preacher) of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd ''tirthankara'' Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6t ...

(6th century BCE). Tirukkural

The ''Tirukkuṟaḷ'' ( ta, திருக்குறள், lit=sacred verses), or shortly the ''Kural'' ( ta, குறள்), is a classic Tamil language text consisting of 1,330 short couplets, or Kural (poetic form), kurals, of seven ...

, dated to late 5th century CE, contains chapters on veganism or moral vegetarianism, emphasizing unambiguously on non-animal diet (Chapter 26), non-harming (Chapter 32), and non-killing (Chapter 33).

Not everyone who refused to participate in any killing or injuring of animals also abstained from the consumption of meat. Hence the question of Buddhist vegetarianism

Buddhist vegetarianism is the practice of vegetarianism by significant portions of Mahayana Buddhist monks and nuns (as well as laypersons) and some Buddhists of other sects. In Buddhism, the views on vegetarianism vary between different schoo ...

in the earliest stages of that religion's development is controversial. There are two schools of thought. One says that the Buddha and his followers ate meat offered to them by hosts or alms-givers if they had no reason to suspect that the animal had been slaughtered specifically for their sake. The other one says that the Buddha and his community of monks (sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

) were strict vegetarians and the habit of accepting alms of meat was only tolerated later on, after a decline of discipline.

The first opinion is supported by several passages in the Pali version of the Tripitaka, the opposite one by some Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

texts. All those sources were put into writing several centuries after the death of the Buddha. They may reflect the conflicting positions of different wings or currents within the Buddhist community in its early stage.Phelps p. 75-77, 83-84. According to the Vinaya Pitaka

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon (''Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (Buddhism), Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinay ...

, the first schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

happened when the Buddha was still alive: a group of monks led by Devadatta

Devadatta was by tradition a Buddhist monk, cousin and brother-in-law of Gautama Siddhārtha. The accounts of his life vary greatly, but he is generally seen as an evil and divisive figure in Buddhism, who led a breakaway group in the ea ...

left the community because they wanted stricter rules, including an unconditional ban on meat eating.

The Mahaparinibbana Sutta, which narrates the end of the Buddha's life, states that he died after eating ''sukara-maddava'', a term translated by some as ''pork'', by others as ''mushrooms'' (or an unknown vegetable).

The Buddhist emperor Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

(304–232 BCE) was a vegetarian, and a determined promoter of nonviolence to animals. He promulgated detailed laws aimed at the protection of many species, abolished animal sacrifice at his court, and admonished the population to avoid all kinds of unnecessary killing and injury. Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

has asserted protection to fauna, from his edicts:

Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

Buddhists used to observe the regulation of the Pali canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During th ...

which allowed them to eat meat unless the animal had been slaughtered specifically for them. In the Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

school some scriptures advocated vegetarianism; a particularly uncompromising one was the famous Lankavatara Sutra written in the fourth or fifth century CE.

Hinduism

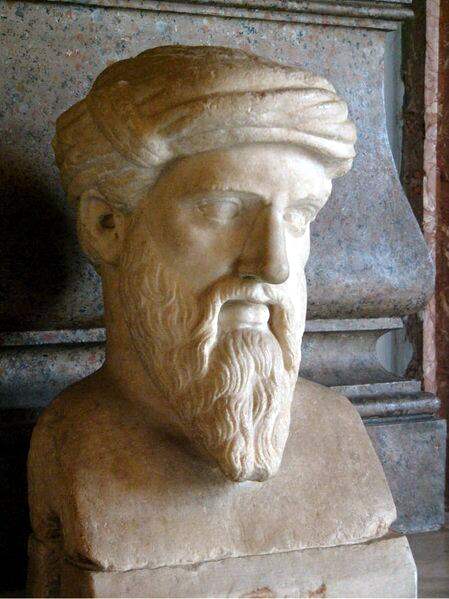

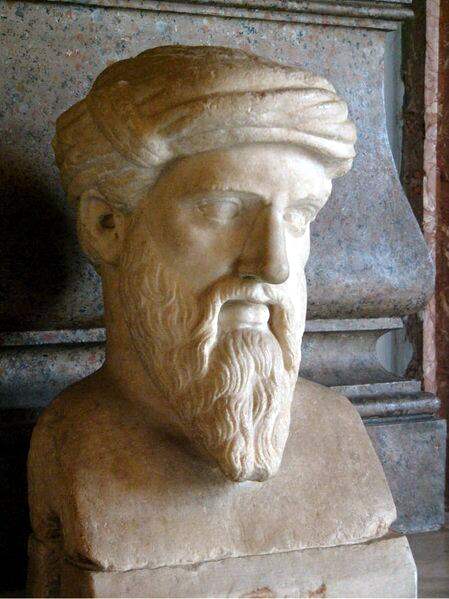

Philosopher

Philosopher Michael Allen Fox

Michael Allen Fox (born 7 May 1940) is an American/Canadian/Australian philosopher who was based at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario from 1966 until his retirement in 2005. He is the author of a number of books, including ''The Case for ...

asserts that "Hinduism has the most profound connection with a vegetarian way of life and the strongest claim to fostering and supporting it." In the ancient Vedic period (between 1500 and 500 BCE), although the laws allowed the consumption of some kinds of meat, vegetarianism was encouraged. Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

yields several foundations for vegetarianism as the Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

, the oldest and sacred texts of Hinduism, assert that all creatures manifest the same life force and therefore merit equal care and compassion. A number of Hindu texts place injunctions against meat eating and others like the Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th ...

and Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the ''Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kuruk ...

advocate for a vegetarian diet. In Hinduism, killing a cow is traditionally considered a sin.Spencer, Colin. The heretics feast: a history of vegetarianism. University Press of New England, 1996

Vegetarianism was, and still is, mandatory for Hindu yogis

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions.A. K. Banerjea (2014), ''Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha'', Motilal Banarsidass, , pp. xxiii, 297-299, 331 T ...

, both for the practitioners of Hatha Yoga

Haṭha yoga is a branch of yoga which uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel the vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ ''haṭha'' literally means "force", alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some haṭha ...

and for the disciples of the Vaishnava

Vaishnavism ( sa, वैष्णवसम्प्रदायः, Vaiṣṇavasampradāyaḥ) is one of the major Hindu denominations along with Shaivism, Shaktism, and Smartism. It is also called Vishnuism since it considers Vishnu as the ...

schools of Bhakti Yoga

Bhakti yoga ( sa, भक्ति योग), also called Bhakti marga (, literally the path of ''Bhakti''), is a spiritual path or spiritual practice within Hinduism focused on loving devotion towards any personal deity.Karen Pechelis (2014), ...

(especially the Gaudiya Vaishnavas

Gaudiya Vaishnavism (), also known as Chaitanya Vaishnavism, is a Vaishnava Hindu religious movement inspired by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534) in India. "Gaudiya" refers to the Gaura or Gauḍa region of Bengal, with Vaishnavism meanin ...

). A ''bhakta'' (devotee) offers all his food to Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" within t ...

or Krishna

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is one ...

as prasad

200px, Prasad thaal offered to Swaminarayan temple in Ahmedabad ">Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, Ahmedabad">Swaminarayan temple in Ahmedabad

Prasada (, Sanskrit: प्रसाद, ), Prasadam or Prasad is a religious offering in Hinduism. Most o ...

before eating it. Only vegetarian food can be accepted as prasad. According to Yogic thought, ''saatvik'' food (pure or having good impact on body) is meant to calm and purify the mind "enabling it to function at its maximum potential" and keep the body healthy. Saatvik foods consist of "cereals, fresh fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts, sprouted seeds, whole grains and milk taken from a cow, which is allowed to have a natural birth, life and death including natural food, after satiating the needs of milk of its calf". Many Vaishnava schools avoid vegetables such as onion, garlic, leek, radish, carrot, brinjal (eggplant), bottlegourd, mushroom, red lentils etc. as they are considered to have non-saatvik effects on the body.

Shankar Narayan suggests that the origin of vegetarianism in India developed from the idea that balance needed to be restored. He claims, "Along with the development in civilisation, savagery also increased and those who were helpless and voiceless among both humans and non-human animals were more and more exploited and killed to satiate human needs and greed thus disturbing the balance of nature. But there were also many serious attempts to bring back the humanity to sanity and restore balance from time to time." He also says that the idea of living in harmony with nature became central to the rulers and kings.Narayan, Vn.Shankar. 'Origin & History of Vegetarianism in India'. 38th IVU World Vegetarian Congress (Centenary Congress) at the Festsaal, Kulturpalast, Dresden, Germany, 2008.

Zoroastrianism

Followers ofIlm-e-Kshnoom

Ilm-e-Khshnoom ('science of ecstasy', or 'science of bliss') is a school of Zoroastrian thought, practiced by a very small minority of the Indian Zoroastrians (Parsis/ Iranis), based on a mystic and esoteric, rather than literal, interpretation of ...

, a school of Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic on ...

thought found in India, practice vegetarianism, and follow other currently non-traditional opinions. Although there have been various theological statements supporting vegetarianism in Zoroastrianism's history and claims that Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label=New Persian, Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastria ...

was vegetarian.

Mediterranean Basin

Ancient Greece

InAncient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

during Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the vegetarian diet was called ''abstinence from beings with a soul'' ( grc, ἀποχὴ ἐμψύχων). As a principle or deliberate way of life it was always limited to a rather small number of practitioners belonging to specific philosophical schools or certain religious groups. The earliest European/Asian Minor references to a vegetarian diet occur in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

(''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'' 9, 82–104) and Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

(4, 177), who mention the Lotophagi

In Greek mythology, the lotus-eaters ( grc-gre, λωτοφάγοι, lōtophágoi) were a race of people living on an island dominated by the lotus tree, a plant whose botanical identity is uncertain. The lotus fruits and flowers were the primar ...

(Lotus-eaters), an indigenous people on the North African coast, who according to Herodotus lived on nothing but the fruits of a plant called lotus. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

(3, 23–24) transmits tales of vegetarian peoples or tribes in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, and further stories of this kind are narrated and discussed in ancient sources.

The earliest reliable evidence for vegetarian theory and practice in Greece dates from the 6th century BCE. The Orphics

Orphism (more rarely Orphicism; grc, Ὀρφικά, Orphiká) is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus ...

, a religious movement spreading in Greece at that time, may have practiced vegetarianism.Spencer p. 38-55, 61-63; Haussleiter p. 79-157. It is unclear whether the Greek religious teacher Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

actually advocated vegetarianism and it is more likely that Pythagoras only prohibited certain kinds of meat. Later writers presented Pythagoras as prohibiting meat altogether. Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; grc, Εὔδοξος ὁ Κνίδιος, ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar, and student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original works are lost, though some fragments are ...

, a student of Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed founder ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, writes that "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters". Behind Pythagoras’ rejection of eating meat were ethical considerations. He believed that animals possess both intelligence and passion (the critical elements for sentience) and because of that their mistreatment was unethical.

The followers of Pythagoras (called Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

) did not always practice strict vegetarianism, but at least their inner circle did. For the general public, abstention from meat was a hallmark of the so-called "Pythagorean way of life". Both Orphics and strict Pythagoreans also avoided eggs and shunned the ritual offerings of meat to the gods which were an essential part of traditional religious sacrifice. In the 5th century BCE the philosopher Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the fo ...

distinguished himself as a radical advocate of vegetarianism specifically and of respect for animals in general. A fictionalized portrayal of Pythagoras appears in Book XV of Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the wo ...

'', in which he advocates a form of strict vegetarianism. It was through this portrayal that Pythagoras was best known to English-speakers throughout the early modern period and, prior to the coinage of the word "vegetarianism", vegetarians were referred to in English as "Pythagoreans".

The question of whether there are any ethical duties toward animals was hotly debated, and the arguments in dispute were quite similar to the ones familiar in modern discussions on animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

. Vegetarianism was usually part and parcel of religious convictions connected with the concept of transmigration of the soul

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

(metempsychosis

Metempsychosis ( grc-gre, μετεμψύχωσις), in philosophy, is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualised by modern philoso ...

). There was a widely held belief, popular among both vegetarians and non-vegetarians, that in the Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

of the beginning of humanity mankind was strictly non-violent. In that utopian state of the world hunting, livestock breeding, and meat-eating, as well as agriculture were unknown and unnecessary, as the earth spontaneously produced in abundance all the food its inhabitants needed. This myth is recorded by Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

(''Works and Days'' 109sqq.), Plato (''Statesman'' 271–2), the famous Roman poet Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

(''Metamorphoses'' 1,89sqq.), and others. Ovid also praised the Pythagorean ideal of universal nonviolence (''Metamorphoses'' 15,72sqq.).

Almost all the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

were emphatically anti-vegetarian (with the prominent exception of Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

). They insisted on the absence of reason in brutes, leading them to conclude that there cannot be any ethical obligations or restraints in dealing with the world of irrational animals. As for the followers of the Cynic school, their extremely frugal way of life entailed a practically meatless diet, but they did not make vegetarianism their maxim.

In the Platonic Academy

The Academy (Ancient Greek: Ἀκαδημία) was founded by Plato in c. 387 BC in Classical Athens, Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years (367–347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum. The Academy ...

, the scholarchs (school heads) Xenocrates

Xenocrates (; el, Ξενοκράτης; c. 396/5314/3 BC) of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader (scholarch) of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted to d ...

and (probably) Polemon pleaded for vegetarianism. In the Peripatetic school Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

, Aristotle's immediate successor, supported it. Some of the prominent Platonists and Neo-Platonists in the age of the Roman Empire lived on a vegetarian diet. These included Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεύς; c. 3 BC – c. 97 AD) was a Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from the town of Tyana in the Roman province of Cappadocia in Anatolia. He is the subject of ''L ...

, Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neop ...

, and Porphyry. Porphyry wrote a treatise “On abstinence from animal food”, the most elaborate ancient pro-vegetarian text known to us. Porphyry believed that animals are aware and capable of evaluating situations, have memory, and can communicate. He urged that by consuming meat, the body becomes corrupt and unhealthy, leading to obesity. Porphyry maintained that killing an animal is no different from taking the life of a human being – and thus became one of the first to state that animal life is equal to that of a human.

Among the Manicheans

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (AD ...

, a major religious movement founded in the third century CE, there was an elite group called ''Electi'' (the chosen) who were Lacto-Vegetarians for ethical reasons and abided by a commandment which strictly banned killing. Common Manicheans called ''Auditores'' (Hearers) obeyed looser rules of nonviolence.

Judaism

A small number of Jewish scholars throughout history have argued that theTorah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

provides a scriptural basis for vegetarianism, now or in the Messianic Age

In Abrahamic religions, the Messianic Age is the future period of time on Earth in which the messiah will reign and bring universal peace and brotherhood, without any evil. Many believe that there will be such an age; some refer to it as the consu ...

. Some writers assert that the Jewish prophet Isaiah was a vegetarian. A number of ancient Jewish sects, including early Karaite sects, regarded the eating of meat as prohibited, at least while Israel was in exile, and medieval scholars such as Joseph Albo

Joseph Albo ( he, יוסף אלבו; c. 1380–1444) was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who lived in Spain during the fifteenth century, known chiefly as the author of ''Sefer ha-Ikkarim'' ("Book of Principles"), the classic work on the fundamenta ...

and Isaac Arama Isaac ben Moses Arama ( 1420 – 1494) was a Spanish rabbi and author. He was at first principal of a rabbinical academy at Zamora (probably his birthplace); then he received a call as rabbi and preacher from the community at Tarragona, and later ...

regarded vegetarianism as a moral ideal, out of a concern for the moral character of the slaughterer.

East and Southeast Asia

China

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, ...

and Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of Philosophy, philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of China, Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmo ...

require that monks and nuns eat an egg free, onion free vegetarian diet. Since abbeys were usually self-sufficient, in practice, this meant they ate a vegan diet. Many religious orders also avoid hurting plant life by avoiding root vegetables. This is not just seen as an ascetic practice, but Chinese spirituality generally believes that animals have immortal souls, and that a diet of mostly grain is the healthiest for humans.

In Chinese folk religions, as well as the aforementioned faiths, people often eat vegan on the 1st and 15th of the month, as well as the eve of Chinese New Year. Some nonreligious people do this as well. This is similar to the Christian practice of lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

and not eating meat on Friday. The percentage of people permanently being pure vegetarian is about the same as the modern English-speaking world, but this percentage has not really changed for a very long time. Many people eat vegan for a certain amount of time in order to make up for the belief that they have sinned.

Foods like seitan

Seitan (, ; Japanese: セイタン) is a food made from gluten, the main protein of wheat.

It is also known as miànjīn (), fu (Japanese: 麩), milgogi (Korean: 밀고기), wheat meat, gluten meat, vital wheat gluten or simply gluten. It is ma ...

, tofu skin

Tofu skin, Yuba, beancurd skin, beancurd sheet, or beancurd robes is a food product made from soybeans. During the boiling of soy milk, in an open shallow pan, a film or skin composed primarily of a soy protein-lipid complex forms on the liquid s ...

, meat alternatives made from seaweeds, root vegetable starch, and tofu

Tofu (), also known as bean curd in English, is a food prepared by coagulating soy milk and then pressing the resulting curds into solid white blocks of varying softness; it can be ''silken'', ''soft'', ''firm'', ''extra firm'' or ''super firm ...

originate in China and became popularized because so many people periodically abstain from meat. In China, one can find an eggless vegetarian substitute for items ranging from seafood to ham. Also, the Thai (เจ) and Vietnamese (chay) terms for vegetarianism originate from the Chinese term for a lenten diet.

Japan

In 675, the use of

In 675, the use of livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to animals ...

and the consumption of some wild animals (horse, cattle, dogs, monkeys, birds) was banned in Japan by Emperor Tenmu

was the 40th emperor of Japan, Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'') 天武天皇 (40) retrieved 2013-8-22. according to the traditional order of succession. Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). ''The Imperial House of Japan'', p. 53.

Tenmu's re ...

, due to the influence of Buddhism. Subsequently, in the year 737 of the Nara period, the Emperor Seimu

, also known as , was the 13th legendary Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Both the ''Kojiki'', and the ''Nihon Shoki'' (collectively known as the ''Kiki'') record events that took place during Seimu's alleged l ...

approved the eating of fish and shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

. During the twelve hundred years from the Nara period

The of the history of Japan covers the years from CE 710 to 794. Empress Genmei established the capital of Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara). Except for a five-year period (740–745), when the capital was briefly moved again, it remained the cap ...

to the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

in the latter half of the 19th century, Japanese people enjoyed vegetarian-style meals. They usually ate rice as a staple food as well as beans and vegetables. It was only on special occasions or celebrations that fish was served. Over this period, the Japanese people (particularly Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

monks) developed a vegetarian cuisine called ''shōjin-ryōri

Buddhist cuisine is an Asian cuisine that is followed by monks and many believers from areas historically influenced by Mahayana Buddhism. It is vegetarian or vegan, and it is based on the Dharmic concept of ahimsa (non-violence). Vegetarian ...

'' which was native to Japan. ''ryōri'' means cooking or cuisine, while ''shojin'' is a Japanese translation of '' virya'' in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, meaning "to have the goodness and keep away evils".

In 1872 of the Meiji restoration, as part of the opening up of Japan to Western influence, Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

lifted the ban on the consumption of red meat

In gastronomy, red meat is commonly red when raw and a dark color after it is cooked, in contrast to white meat, which is pale in color before and after cooking. In culinary terms, only flesh from mammals or fowl (not fish) is classified as ...

. The removal of the ban encountered resistance and in one notable response, ten monks attempted to break into the Imperial Palace. The monks asserted that due to foreign influence, large numbers of Japanese had begun eating meat and that this was "destroying the soul of the Japanese people." Several of the monks were killed during the break-in attempt, and the remainder were arrested.

Orthodox Christianity

In Greek-Orthodox Christianity (Greece, Cyprus, Russia, Serbia and other Orthodox countries), adherents eat a diet completely free of animal products for fasting periods (except for honey) as well as all types of oil and alcohol, during a strict fasting period. TheEthiopian Orthodox Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

prescribes a number of fasting (tsom, Ge'ez: ጾም ṣōm, excluding any kind of animal products, including dairy products and eggs) periods, including Wednesdays, Fridays, and the entire Lenten season, so Ethiopian cuisine contains many dishes that are vegan.

Christian antiquity and Middle Ages

The leaders of the early Christians in the apostolic era (James, Peter, and John) were concerned that eating food sacrificed to idols might result in ritual pollution. The only food sacrificed to idols was meat. The Apostle Paul emphatically rejected that view which resulted in division of an Early Church (Romans 14:2-21; compare 1 Corinthians 8:8-9, Colossians 2:20-22). Many early Christians were vegetarian such asClement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and ...

, Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

, Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

, John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

, Basil the Great

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Ca ...

, and others. Some early church writings suggest that Matthew, Peter, and James were vegetarian. The historian Eusebius writes that the Apostle "Matthew partook of seeds, nuts and vegetables, without flesh." The philosopher Porphyry wrote an entire book entitled ''On Abstinence from Animal Food'' which compiled most of the classical thought on the subject.

In late antiquity and in the Middle Ages many monks and hermits renounced meat-eating in the context of their asceticism. The most prominent of them was St Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

(† 419), whom they used to take as their model. The Rule of St Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's R ...

(6th century) allowed the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

s to eat fish and fowl, but forbade the consumption of the meat of quadrupeds unless the religious was ill. Many other rules of religious orders contained similar restrictions of diet, some of which even included fowl, but fish was never prohibited, as Jesus himself had eaten fish (Luke 24:42-43). The concern of those monks and nuns was frugality, voluntary privation, and self-mortification. William of Malmesbury writes that Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester

Wulfstan ( – 20 January 1095) was Bishop of Worcester from 1062 to 1095. He was the last surviving pre-Conquest bishop. Wulfstan is a saint in the Western Christian churches.

Denomination

His denomination as Wulfstan II is to indicate t ...

(d. 1095) decided to adhere to a strict vegetarian diet simply because he found it difficult to resist the smell of roasted goose. Saint Genevieve

Genevieve (french: link=no, Sainte Geneviève; la, Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; 419/422 AD –

502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church, Orthodox traditions. Her Calendar of sain ...

, the Patron Saint of Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, is mentioned as having observed a vegetarian diet—but as an act of physical austerity, rather than out of concern for animals. Medieval hermits, at least those portrayed in literature, may have been vegetarians for similar reasons, as suggested in a passage from Sir Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'Ar ...

's ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Rou ...

'': 'Then departed Gawain and Ector as heavy (sad) as they might for their misadventure, and so rode till that they came to the rough mountain, and there they tied their horses and went on foot to the hermitage. And when they were come up, they saw a poor house, and beside the chapel a little courtelage, where Nacien the hermit gathered worts, as he which had tasted none other meat of a great while.'

John Passmore claimed that there was no surviving textual evidence for ethically motivated vegetarianism in either ancient and medieval Catholicism or in the Eastern Churches. There were instances of compassion to animals, but no explicit objection to the act of slaughter per se. The most influential theologians, St Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

and St Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

, emphasized that man owes no duties to animals. Although St. Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

described animal beings with mystic language, contemporary sources do not claim that he practised or advocated vegetarianism.

Many ancient intellectual dissidents, such as the Encratites

The Encratites ("self-controlled") were an ascetic 2nd-century sect of Christians who forbade marriage and counselled abstinence from meat. Eusebius says that Tatian was the author of this heresy. It has been supposed that it was these Gnostic Enc ...

, the Ebionites

Ebionites ( grc-gre, Ἐβιωναῖοι, ''Ebionaioi'', derived from Hebrew (or ) ''ebyonim'', ''ebionim'', meaning 'the poor' or 'poor ones') as a term refers to a Jewish Christian sect, which viewed poverty as a blessing, that existed during ...

, and the Eustathians who followed the fourth century monk Eustathius of Antioch

Eustathius of Antioch, sometimes surnamed the Great, was a Christian bishop and archbishop of Antioch in the 4th century. His feast day in the Eastern Orthodox Church is February 21.

Life

He was a native of Side in Pamphylia. About 320 he was bi ...

, considered abstention from meat-eating an essential part of their asceticism. Medieval Paulician

Paulicianism ( Classical Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, ; grc, Παυλικιανοί, "The followers of Paul"; Arab sources: ''Baylakānī'', ''al Bayāliqa'' )Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the ...

Adoptionists

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an early Christian nontrinitarian theological doctrine, which holds that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ascension. How common adoptionist views w ...

, such as the Bogomils

Bogomilism ( Bulgarian and Macedonian: ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic or dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar P ...

("Friends of God") of the Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

area in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

and the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

dualist

Dualism most commonly refers to:

* Mind–body dualism, a philosophical view which holds that mental phenomena are, at least in certain respects, not physical phenomena, or that the mind and the body are distinct and separable from one another

** ...

Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Fol ...

, also despised the consumption of meat.

Early modern period

It was during the

It was during the European Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

that vegetarianism reemerged in Europe as a philosophical concept based on an ethical motivation. Among the first celebrities who supported it were Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

(1452–1519) and Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi; 22 January 1592 – 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he also spent much tim ...

(1592–1655).Stuart, Tristram: ''The Bloodless Revolution. A Cultural History of Vegetarianism from 1600 to Modern Times'', New York 2007 In the 17th century the paramount theorist of the meatless or Pythagorean diet

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

was the English writer Thomas Tryon

Thomas Tryon (6 September 1634 – 21 August 1703) was an English sugar merchant, author of popular self-help books, and early advocate of animal rights and vegetarianism. Life

Born in 1634 in Bibury near Cirencester, Gloucestershire, England, ...

(1634–1703) and subsequently the Romantic poets

Romantic poetry is the poetry of the Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. It involved a reaction against prevailing Enlightenment ideas of the 18t ...

. On the other hand, influential philosophers such as René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

(1596–1650) and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

(1724–1804) were of the opinion that there cannot be any ethical duties whatsoever toward animals—though Kant also observes that "He who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men. We can judge the heart of a man by his treatment of animals." By the end of the 18th century in England the claim that animals were made only for man's use (anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism (; ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. F ...

) was still being advanced, but no longer carried general assent. Very soon, it would disappear altogether.

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, there were small groups of Christian vegetarian

Christian vegetarianism is the practice of keeping to a vegetarian lifestyle for reasons connected to or derived from the Christian faith. The three primary reasons are spiritual, nutritional, and ethical. The ethical reasons may include a con ...

s in the 18th century. The best known of them was Ephrata Cloister

The Ephrata Cloister or Ephrata Community was a Intentional community, religious community, established in 1732 by Conrad Beissel, Johann Conrad Beissel at Ephrata, Pennsylvania, Ephrata, in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Lancaster ...

in Pennsylvania, a religious community founded by Conrad Beissel

Johann Conrad Beissel (March 1, 1691 – July 6, 1768) was a German-born religious leader who in 1732 founded the Ephrata Community in the Province of Pennsylvania.For the correct date of his birth see Alderfer, Everett Gordon: ''The Ephrata Comm ...

in 1732. Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

became a vegetarian at the age of 16, but later on he ''reluctantly'' returned to meat eating. He later introduced tofu

Tofu (), also known as bean curd in English, is a food prepared by coagulating soy milk and then pressing the resulting curds into solid white blocks of varying softness; it can be ''silken'', ''soft'', ''firm'', ''extra firm'' or ''super firm ...

to America in 1770.

Colonel Thomas Crafts Jr. was a vegetarian.

19th century

Vegetarianism was frequently associated with cultural reform movements, such astemperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

and anti-vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

. It was propagated as an essential part of "the natural way of life." Some of its champions sharply criticized the civilization of their age and strove to improve public health.

Great Britain

During the

During the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

and in the early nineteenth century, England was the place where vegetarian ideas were more welcome than anywhere else Europe, and the English vegetarians were particularly enthusiastic about the practical implementation of their principles. In England, vegetarianism was strongest in the northern and middle regions, specifically urbanized areas. As the movement spread across the country, more working-class people began to identify as vegetarians, though still a small number in comparison to the number of meat eaters. Groups were established all across England, but the movement failed to gain popular support and was drowned out by other, more exciting, struggles of the late-nineteenth century.

In 1802, Joseph Ritson

Joseph Ritson (2 October 1752 – 23 September 1803) was an English antiquary who was well known for his 1795 compilation of the Robin Hood legend. After a visit to France in 1791, he became a staunch supporter of the ideals of the French Revo ...

authored ''An Essay on Abstinence from Animal Food, as a Moral Duty

''An Essay on Abstinence from Animal Food, as a Moral Duty'' is a book on ethical vegetarianism and animal rights written by Joseph Ritson, first published in 1802.

Description

Ritson became a vegetarian in 1772 at the age of 19. He was influ ...

''. Reverend William Cowherd

William Cowherd (1763 – 24 March 1816) was a Christian minister serving a congregation in the City of Salford, England, immediately west of Manchester, and one of the philosophical forerunners of the Vegetarian Society founded in 1847.; Gregory ...

founded the Bible Christian Church

The Bible Christian Church was a Methodist denomination founded by William O’Bryan, a Wesleyan Methodist local preacher, on 18 October 1815 in North Cornwall. The first society, consisting of just 22 members, met at Lake Farm in Shebbear, ...

in 1809. He advocated vegetarianism as a form of temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

, and his organisation was one of the philosophical forerunners of the Vegetarian Society

The Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom is a British registered charity which was established on 30 September 1847 to promote vegetarianism.

History

In the 19th century a number of groups in Britain actively promoted and followed meat ...

. Martha Brotherton authored '' Vegetable Cookery'', the first vegetarian cookbook, in 1812.

A prominent advocate of an ethically motivated vegetarianism in the early 19th century was the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 17928 July 1822) was one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame during his lifetime, but recognition of his achie ...

(1792–1822). He was influenced by John Frank Newton's ''Return to Nature, or, Defence of the Vegetable Regimen'' (1811), and he published an essay on the subject in 1813, ''A Vindication of Natural Diet

''A Vindication of Natural Diet'' is an 1813 book by Percy Bysshe Shelley on vegetarianism and animal rights. It was first written as part of the notes to ''Queen Mab'', which was privately printed in 1813. Later in the same year the essay was s ...

''.

The first Vegetarian Society of the modern western world was established in England in 1847. The Society was founded by the 140 participants of a conference at Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

and by 1853 had 889 members. By the end of the century, the group had attracted almost 4,000 members. After its first year, alone, the group grew to 265 members that ranged from ages 14 to 76. English vegetarians were a small but highly motivated and active group. Many of them believed in a simple life

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

and "pure" food, humanitarian ideals and strict moral principles. Not all members of the Vegetarian Society were "Cowherdites", though they constituted about half of the group.

''The Cornishman

''The Cornishman'' is a weekly newspaper based in Penzance, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom which was first published on 18 July 1878. Circulation for the first two editions was 4,000. An edition is currently printed every Thursday. In early Fe ...

'' newspaper reported in March 1880 that a vegetarian restaurant had existed in Manchester for some years and one had just opened in Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch via Oxford Circus. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, with around half a million daily visitors, and as ...

, London.

Class

Class played prominent roles in the Victorian vegetarian movement. There was somewhat of a disconnect when the upper-middle class attempted to reach out to the working and lower classes. Though the meat industry was growing substantially, many working class Britons had mostly vegetarian diets out of necessity rather than out of the desire to improve their health and morals. The working class did not have the luxury being able to choose what they would eat and they believed that a mixed diet was a valuable source of energy.Women

Tied closely with other social reform movements, women were especially visible as the "mascot". When late-Victorians sought to promote their cause in journal, female angels or healthy English women were the images most commonly depicted. Two prominent female vegetarians were Elizabeth Horsell, author of a vegetarian cookbook and a lecturer (and wife ofWilliam Horsell

William Horsell (31 March 1807 – 23 December 1863) was an English hydrotherapist, publisher, and temperance and vegetarianism activist. Horsell published the first vegan cookbook in 1849.

Biography

Horsell was born in Brinkworth, Wiltshire. B ...

), and Jane Hurlstone. Hurlstone was active in Owenism, animal welfare, and Italian nationalism as well. Though women were regularly overshadowed by men, the newspaper the ''Vegetarian Advocate'' noted that women were more inclined to do work in support of vegetarianism and animal welfare than men, who tended to only speak on the matter. In a domestic setting, women promoted vegetarianism though cooking vegetarian dishes for public dinners and arranging entertainment that promoted the cause. Outside of the domestic sphere, Victorian women edited vegetarian journals, wrote articles, lectured, and wrote cookbooks. Of the 26 vegetarian cookbooks published during the Victorian Age, 14 were written by women.

In 1895, The Women's Vegetarian Union was established by Alexandrine Veigele, a French woman living in London. The organization aimed to promote a 'purer and simpler' diet and they regularly reached out to the working class.

The morality arguments behind vegetarianism in Victorian England drew idealists from various causes together. Specifically, many vegetarian women identified as feminists. In her feminist utopia

Utopian and dystopian fiction are genres of speculative fiction that explore social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal t ...

, '' Herland'' (1915), Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, advocate for social reform, and eugenicist. She wa ...

imagined a vegetarian society. Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

also advocated for vegetarianism in her work, ''Women of the Nineteenth Century'' (1845). She argued that when women are liberated from domestic life, they would help transform the violent male society, and vegetarianism would become the dominant diet. Frances Power Cobbe

Frances Power Cobbe (4 December 1822 – 5 April 1904) was an Anglo-Irish writer, philosopher, religious thinker, social reformer, anti-vivisection activist and leading women's suffrage campaigner. She founded a number of animal advocacy group ...

, a co-founder of the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection

Cruelty Free International is an animal protection and advocacy group that campaigns for the abolition of all animal experiments. They organise certification of cruelty-free products which are marked with the symbol of a leaping bunny.

It was ...

, identified as a vegetarian and was a well-known activist for feminism. Many of her colleagues in the first-wave feminist movement also identified as vegetarians.

United States

In 1835, Asenath Nicholson authored the first American vegetarian cookbook. In 1845, the vegetarian newspaper '' The Pleasure Boat'' began publication. In the United States, Reverend William Metcalfe (1788–1862), a pacifist and a prominent member of the Bible Christian Church, preached vegetarianism. He andSylvester Graham

Sylvester Graham (July 5, 1794 – September 11, 1851) was an American Presbyterian minister and dietary reformer known for his emphasis on vegetarianism, the temperance movement, and eating whole-grain bread. His preaching

inspired the graha ...

, the mentor of the Grahamites and inventor of the Graham crackers

A graham cracker (pronounced or in America) is a sweet flavored cracker made with graham flour that originated in the United States in the mid-19th century, with commercial development from about 1880. It is eaten as a snack food, usually ho ...

, were among the founders of the American Vegetarian Society in 1850. In 1838, Dr. William Alcott

William Andrus Alcott (August 6, 1798 – March 29, 1859), also known as William Alexander Alcott, was an American educator, educational reformer, physician, vegetarian and author of 108 books. His works, which include a wide range of topics in ...

published "Vegetable Diet: As Sanctioned by Medical Men, and by Experience in All Ages." The book was reprinted in 2012, and journalist Avery Yale Kamila

Avery Yale Kamila is an American journalist, vegan columnist and community organizer in the state of Maine.

Biography

Kamila was born in Westminster, Massachusetts in the 1970s and grew up on an organic farm in Litchfield, Maine. Kamila adopte ...

called it "a seminal work in the cannon of American vegetarian literature."

Ellen G. White

Ellen Gould White (née Harmon; November 26, 1827 – July 16, 1915) was an American woman author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she wa ...

, one of the founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

, became an advocate of vegetarianism, and the Church has recommended a meatless diet ever since. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg

John Harvey Kellogg (February 26, 1852 – December 14, 1943) was an American medical doctor, nutritionist, inventor, health activist, eugenicist, and businessman. He was the director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan. The ...

(of corn flakes

Corn flakes, or cornflakes, are a breakfast cereal made from toasting flakes of corn (maize). The cereal, originally made with wheat, was created by Will Kellogg in 1894 for patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium where he worked with his broth ...

fame), a Seventh-Day Adventist, promoted vegetarianism at his Battle Creek Sanitarium

The Battle Creek Sanitarium was a world-renowned health resort in Battle Creek, Michigan, United States. It started in 1866 on health principles advocated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church and from 1876 to 1943 was managed by Dr. John ...

as part of his theory of "biologic living".

American vegetarians such as Isaac Jennings

Isaac Jennings (November 7, 1788 March 13, 1874) was an American physician and writer who pioneered orthopathy (natural hygiene).

Biography

Jennings was born on November 7, 1788 in Fairfield, Connecticut.Orcutt, Samuel; Beardsley, Ambrose. (1 ...

, Susanna W. Dodds, M. L. Holbrook and Russell T. Trall

Russell Thacher Trall (August 5, 1812 – September 23, 1877) was an American physician and proponent of hydrotherapy, Orthopathy, natural hygiene and vegetarianism. Trall authored the first American Veganism, vegan cookbook in 1874.

Biography

...

were associated with the natural hygiene movement.

Other countries

In Russia,

In Russia, Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

(1828–1910) was the most outstanding supporter of vegetarianism.

In Germany, the well-known politician, publicist and revolutionist Gustav Struve

Gustav Struve, known as Gustav von Struve until he gave up his title (11 October 1805 in Munich, Bavaria – 21 August 1870 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary), was a German surgeon, politician, lawyer and publicist, and a revolutionary during the Germa ...

(1805–1870) was a leading figure in the initial stage of the vegetarian movement. He was inspired by Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

's treatise '' Emile: or, On Education''. Many vegetarian associations were founded in the last third of the century and the Order of the Golden Age went on to achieve particular prominence beyond the Food Reform movement. In 1886, a German colonist couple, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche

Therese Elisabeth Alexandra Förster-Nietzsche (10 July 1846 – 8 November 1935) was the sister of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the creator of the Nietzsche Archive in 1894.

Förster-Nietzsche was two years younger than her brother ...

and Bernhard Förster

Ludwig Bernhard Förster (31 March 1843 – 3 June 1889) was a German teacher. He was married to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the sister of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Life

Förster became a leading figure in the anti-Semitic ...

, emigrated to the Paraguayan

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

rainforest and founded Nueva Germania

Nueva Germania (New Germania, german: Neugermanien) is a district of San Pedro Department in Paraguay. It was founded as a German settlement on 23 August 1887 by Bernhard Förster, a German nationalist, who was married to Elisabeth Förster-Niet ...

to put to practice utopian ideas about vegetarianism and the superiority of the Aryan race, though the vegetarian aspect would prove short-lived.

20th century

TheInternational Vegetarian Union

The International Vegetarian Union (IVU) is an international non-profit organization whose purpose is to promote vegetarianism. The IVU was founded in 1908 in Dresden, Germany.

It is an umbrella organisation, which includes organisations from ...

, a union of the national societies, was founded in 1908. In the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

, the popularity of vegetarianism grew during the 20th century as a result of nutritional, ethical, and more recently, environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

and economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

concerns. The IVU's 1975 World Vegetarian Congress in Orono, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

caused a significant impact on to the country's vegetarian movement.

Henry Stephens Salt

Henry Shakespear Stephens Salt (; 20 September 1851 – 19 April 1939) was an English writer and campaigner for social reform in the fields of prisons, schools, economic institutions, and the treatment of animals. He was a noted ethical vegeta ...

(1851–1939) and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

(1856–1950) were famous vegetarian activists.

In 1910, physician J. L. Buttner authored the vegetarian book, ''A Fleshless Diet'' which argued that meat is dangerous and unnecessary.E. B. (1910)''A Fleshless Diet: Vegetarianism as a Rational Dietary''

''American Physical Education Review'' 16: 352. Cranks opened in Carnaby Street, London, in 1961, as the first successful vegetarian restaurant in the UK. Eventually there were five Cranks restaurants in London which closed in 2001. The Indian concept of

nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

had a growing impact in the Western world. The model of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, a strong and uncompromising advocate of nonviolence toward animals, contributed to the popularization of vegetarianism in Western countries. The study of Far-Eastern religious and philosophical concepts of nonviolence was also instrumental in the shaping of Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

's principle of "reverence for life", which is still today a common argument in discussions on ethical aspects of diet. But Schweitzer himself started to practise vegetarianism only shortly before his death.

Singer-songwriter, Morrissey

Steven Patrick Morrissey (; born 22 May 1959), known professionally as Morrissey, is an English singer and songwriter. He came to prominence as the frontman and lyricist of rock band the Smiths, who were active from 1982 to 1987. Since then ...

, discussed the idea of vegetarianism on his song and album ''Meat is Murder

''Meat Is Murder'' is the second studio album by English rock band the Smiths, released on 11 February 1985 by Rough Trade Records. It became the band's only studio album to reach number one on the UK Albums Chart, and stayed on the chart for ...

''. His widespread fame and cult status contributed to the popularity of meat-free lifestyles.