History of patent law on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of patents and patent law is generally considered to have started with the

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access. Patenting medicines was particular popular in the mid-eighteenth century and then declined. Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access. Patenting medicines was particular popular in the mid-eighteenth century and then declined. Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by

The Patent and Copyright Clause of the

The Patent and Copyright Clause of the

"Kicking Away the Ladder: How the Economic and Intellectual Histories of Capitalism Have Been Re-Written to Justify Neo-Liberal Capitalism"

''

* Howard B. Rockman, Intellectual Property law for Engineers and Scientists. * Bugbee, Bruce W. Genesis of American Patent and Copyright Law. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press (1967). * Christine MacLeod, Inventing the Industrial Revolution: The English patent system, 1660–1800, Cambridge University Press. * Galvez-Behar, G

La République des inventeurs. Propriété et organisation de l'innovation en France

Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2008.

An Economic History of Patent Institutions

French Patent History

Patents Research Guide (Australian)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Patent Law History of patent law,

Venetian Statute of 1474

The Venetian Patent Statute of March 19, 1474, established in the Republic of Venice the first statutory patent system in Europe, and may be deemed to be the earliest codified patent system in the world. The Statute is written in old Venetian. It ...

.

Early precedents

There is some evidence that some form ofpatent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

rights was recognized in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

. In 500 BCE, in the Greek city of Sybaris

Sybaris ( grc, Σύβαρις; it, Sibari) was an important city of Magna Graecia. It was situated in modern Calabria, in southern Italy, between two rivers, the Crathis (Crati) and the Sybaris (Coscile).

The city was founded in 720 BC ...

(located in what is now southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

), "encouragement was held out to all who should discover any new refinement in luxury, the profits arising from which were secured to the inventor by patent for the space of a year." Charles Anthon, ''A Classical Dictionary: Containing An Account of the Principal Proper Names Mentioned in Ancient Authors, And Intended To Elucidate All The Important Points Connected With The Geography, History, Biography, Mythology, And Fine Arts Of The Greeks And Romans Together With An Account Of Coins, Weights, And Measures, With Tabular Values Of The Same'', Harper & Bros, 1841, page 1273. Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of ...

, writing in the third century CE, cites Phylarchus

Phylarchus ( el, Φύλαρχoς, ''Phylarkhos''; fl. 3rd century BC) was a Greek historical writer whose works have been lost, but not before having been considerably used by other historians whose works have survived.

Life

Phylarchus was a cont ...

in saying that in Sybaris exclusive rights were granted for one year to creators of unique culinary dishes.

In England, grants in the form of letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

were issued by the sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

to inventors who petitioned and were approved: a grant of 1331 to John Kempe and his company is the earliest authenticated instance of a royal grant made with the avowed purpose of instructing the English in a new industry.E Wyndham Hulme, ''The History of the Patent System under the Prerogative and at Common Law'', Law Quarterly Review, vol.46 (1896), pp.141-154. These letters patent provided the recipient with a monopoly to produce particular goods or provide particular services. Another early example of such letters patent was a grant by Henry VI in 1449 to John of Utynam

John of Utynam is the recipient of the first known English patent, granted in 1449 by King Henry VI. John was a master glass-maker from Flanders who came to England to make the windows for Eton College. The patent granted him a 20-year monopoly on ...

, a Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

man, for a twenty-year monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

for his invention.

The first extant Italian patent was awarded by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

in 1416 for a device for turning wool into felt. Soon thereafter, the Republic of Florence

The Republic of Florence, officially the Florentine Republic ( it, Repubblica Fiorentina, , or ), was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany. The republic originated in 1115, when the Fl ...

granted a patent to Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi ( , , also known as Pippo; 1377 – 15 April 1446), considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture, was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor, and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, p ...

in 1421. Specifically, the well-known Florentine architect received a three-year patent for a barge with hoisting gear, that carried marble along the Arno River

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a so ...

.

Development of the modern patent system

Patents were systematically granted inVenice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

as of 1450, where they issued a decree by which new and inventive devices had to be communicated to the Republic in order to obtain legal protection against potential infringers. The period of protection was 10 years.

These were mostly in the field of glass making. As Venetians emigrated, they sought similar patent protection in their new homes. This led to the diffusion of patent systems to other countries.M. Frumkin, "The Origin of Patents", Journal of the Patent Office Society, March 1945, Vol. XXVII, No. 3, pp 143 et Seq.

King Henry II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder bro ...

introduced the concept of publishing the description of an invention in a patent in 1555. The first patent "specification" was to inventor Abel Foullon

Abel Foullon (1513–1563 or 1565, in France) was an author, director of the Mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative ...

for "Usaige & Description de l'holmetre", (a type of rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

.) Publication was delayed until after the patent expired in 1561. Patents were granted by the monarchy and by other institutions like the "Maison du Roi" and the Parliament of Paris. The novelty of the invention was examined by the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at ...

. Digests were published irregularly starting in 1729 with delays of up to 60 years. Examinations were generally done in secret with no requirement to publish a description of the invention. Actual use of the invention was deemed adequate disclosure to the public.

The English patent system evolved from its early medieval origins into the first modern patent system that recognised intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, co ...

in order to stimulate invention; this was the crucial legal foundation upon which the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

could emerge and flourish.

By the 16th century, the English Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

would habitually grant letters patent for monopolies to favoured persons (or people who were prepared to pay for them). Blackstone (same reference) also explains how "letters patent" (Latin ''literae patentes'', "letters that lie open") were so called because the seal hung from the foot of the document: they were addressed "To all to whom these presents shall come" and could be read without breaking the seal, as opposed to "letters close", addressed to a particular person who had to break the seal to read them.

This power was used to raise money for the Crown, and was widely abused, as the Crown granted patents in respect of all sorts of common goods (salt, for example). Consequently, the Court began to limit the circumstances in which they could be granted. After public outcry, James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

was forced to revoke all existing monopolies and declare that they were only to be used for "projects of new invention". This was incorporated into the 1624 Statute of Monopolies in which Parliament restricted the Crown's power explicitly so that the King could only issue letters patent to the inventors or introducers of original inventions for a fixed number of years. It also voided all existing monopolies and dispensations with the exception of:

:...the sole working or making of any manner of new manufactures within this realm to the true and first inventor and inventors of such manufactures which others at the time of making such letters patent and grants shall not use...

The Statute became the foundation for later developments in patent law in England and elsewhere.

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access. Patenting medicines was particular popular in the mid-eighteenth century and then declined. Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access. Patenting medicines was particular popular in the mid-eighteenth century and then declined. Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

for his steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

, established the principles that patents could be issued for improvements of an already existing machine and that ideas or principles without specific practical application could also legally be patented.

This legal system became the foundation for patent law in countries with a common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

heritage, including the United States, New Zealand and Australia. In the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

, inventors could obtain patents through petition to a given colony's legislature. In 1641, Samuel Winslow

Samuel Ellsworth Winslow (April 11, 1862 – July 11, 1940) was an American politician and Republican Congressman from Massachusetts.

Biography

Winslow was born in Worcester, Massachusetts. He spent a year at the Williston Seminary in Easth ...

was granted the first patent in North America by the Massachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court (formally styled the General Court of Massachusetts) is the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name "General Court" is a hold-over from the earliest days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, ...

for a new process for making salt.

Towards the end of the 18th century, and influenced by the philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, the granting of patents began to be viewed as a form of intellectual property right, rather than simply the obtaining of economic privilege. A negative aspect of the patent law also emerged in this period - the abuse of patent privilege to monopolise the market and prevent improvement from other inventors. A notable example of this was the behaviour of Boulton & Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Eng ...

in hounding their competitors such as Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

through the courts, and preventing their improvements to the steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

from being realised until their patent expired.

Consolidation

The modern French patent system was created during theRevolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

in 1791. Patents were granted without examination since inventor's right was considered as a natural one. Patent costs were very high (from 500 to 1500 francs). Importation patents protected new devices coming from foreign countries. The patent law was revised in 1844 - patent cost was lowered and importation patents were abolished. The revision saw the introduction of the '' Breveté SGDG'', which excluded any guarantees that the patented item would actually satisfy its specification.

The Patent and Copyright Clause of the

The Patent and Copyright Clause of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

was proposed in 1787 by James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (February 25, 1746 – August 16, 1825) was an American Founding Father, statesman of South Carolina, Revolutionary War veteran, and delegate to the Constitutional Convention where he signed the United States Constit ...

. In Federalist No. 43

Federalist No. 43 is an essay by James Madison, the forty-third of ''The Federalist Papers''. It was published on January 23, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all ''The Federalist'' papers were published. This paper conti ...

, Madison wrote, "The utility of the clause will scarcely be questioned. The copyright of authors has been solemnly adjudged, in Great Britain, to be a right of common law. The right to useful inventions seems with equal reason to belong to the inventors. The public good fully coincides in both cases with the claims of the individuals."

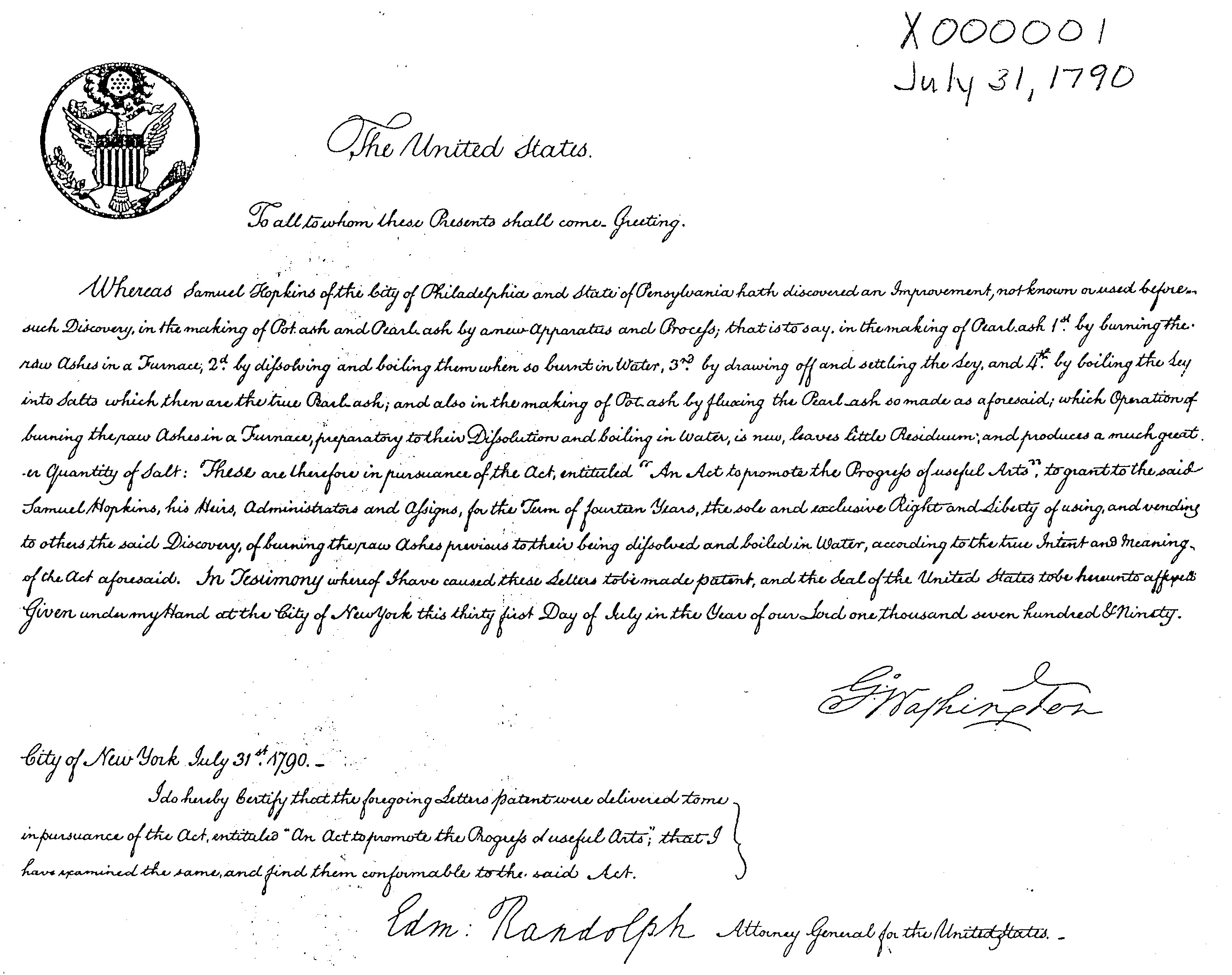

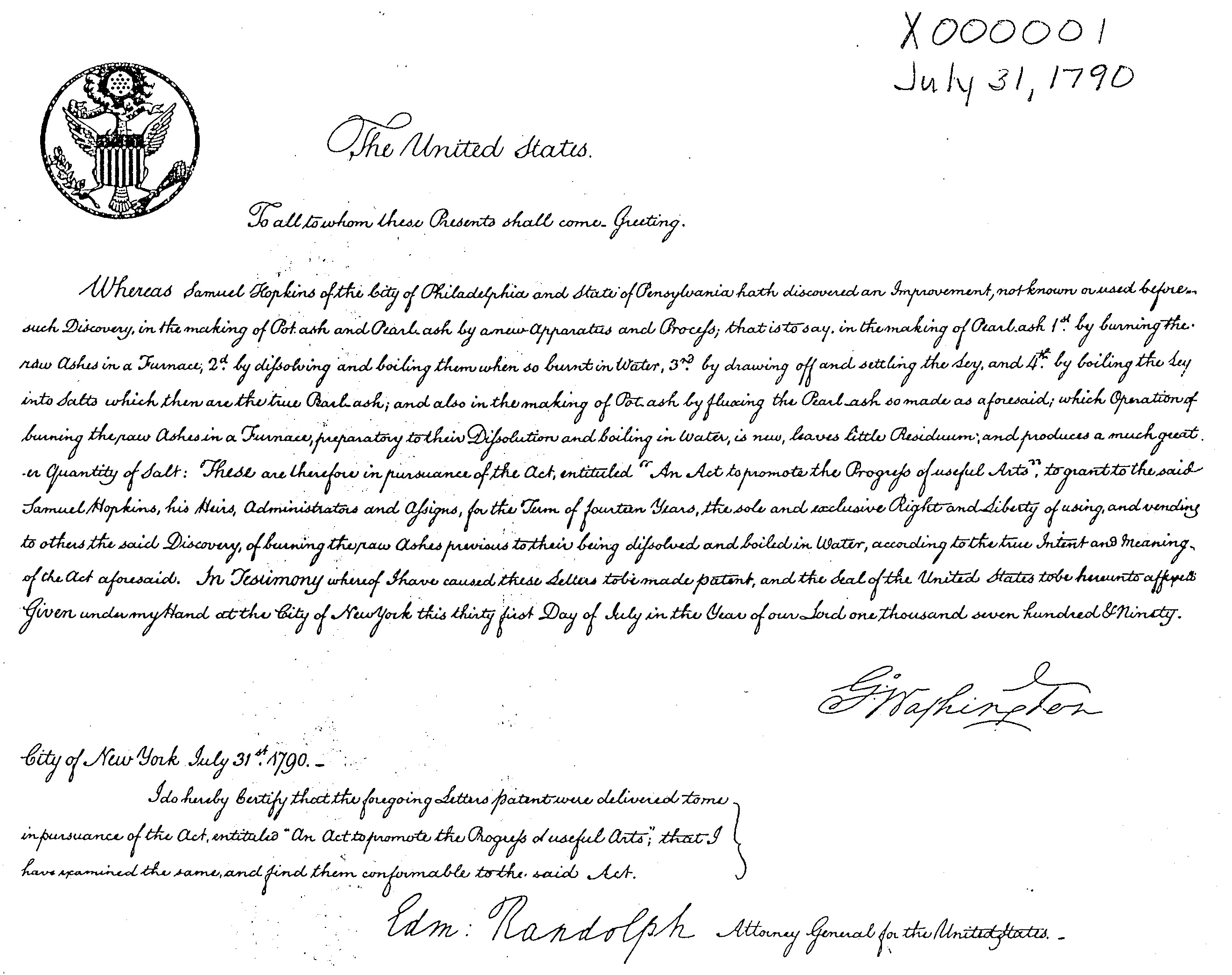

The first Patent Act of the U.S. Congress was passed on April 10, 1790, titled "An Act to promote the progress of useful Arts." The first patent was granted on July 31, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for a method of producing potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

(potassium carbonate).

The earliest law required that a working model of each invention be submitted with the application. Patent applications were examined to determine if an inventor was entitled to the grant of a patent. The requirement for a working model was eventually dropped. In 1793, the law was revised so that patents were granted automatically upon submission of the description. A separate Patent Office was created in 1802.

The patent laws were again revised in 1836, and the examination of patent applications was reinstituted. In 1870 Congress passed a law which mainly reorganized and reenacted existing law, but also made some important changes, such as giving the commissioner of patents the authority to draft rules and regulations for the Patent Office.

Criticism

Under the influence of the ascendant economic philosophy offree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

economics in England, the patent law began to be criticised in the 1850s as obstructing research and benefiting the few at the expense of public good.Johns, Adrian: ''Piracy. The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates''. The University of Chicago Press, 2009, , p.247 The campaign against patenting expanded to target copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educatio ...

too and, in the judgment of historian Adrian Johns

Vice Admiral Sir Adrian James Johns, (born 1 September 1951) is a former senior officer in the Royal Navy, serving as Second Sea Lord between 2005 and 2008. He was the Governor of Gibraltar between 2009 and 2013.

Early life and education

Jo ...

, "remains to this day the strongest ampaignever undertaken against intellectual property", coming close to abolishing patents.

Its most prominent activists - Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

, William Robert Grove

Sir William Robert Grove, FRS FRSE (11 July 1811 – 1 August 1896) was a Welsh judge and physical scientist. He anticipated the general theory of the conservation of energy, and was a pioneer of fuel cell technology. He invented the Grove volt ...

, William Armstrong and Robert A. MacFie - were inventors and entrepreneurs, and it was also supported by radical laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

economists (The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

published anti-patent views), law scholars, scientists (who were concerned that patents were obstructing research) and manufacturers. Johns summarizes some of their main arguments as follows:

:'' atentsprojected an artificial idol of the single inventor, radically denigrated the role of the intellectual commons, and blocked a path to this commons for other citizens — citizens who were all, on this account, potential inventors too. ..Patentees were the equivalent of squatters on public land — or better, of uncouth market traders who planted their barrows in the middle of the highway and barred the way of the people.''

Similar debates took place during that time in other European countries such as France, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

, Switzerland and the Netherlands.Johns, Adrian: ''Piracy'', p. 248 Based on the criticism of patents as state-granted monopolies inconsistent with free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

abolished patents in 1869 (having established them in 1817), and did not reintroduce them until 1912. Chang, Ha-Joon"Kicking Away the Ladder: How the Economic and Intellectual Histories of Capitalism Have Been Re-Written to Justify Neo-Liberal Capitalism"

''

Post-Autistic Economics Review

''Real-World Economics Review'' is a peer-reviewed open access academic journal of heterodox economics published by the "Post-Autistic Economics Network" since 2000. Since 2011 it is associated with the World Economics Association. It was known fo ...

''. 4 September 2002: Issue 15, Article 3. Retrieved on 8 October 2008. In Switzerland, criticism of patents delayed the introduction of patent laws until 1907.

In England, despite much public debate, the system wasn't abolished - it was reformed with the Patent Law Amendment Act of 1852. This simplified procedure for obtaining patents, reduced fees and created one office for the entire United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, instead of different systems for England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is En ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. In France as well, a similar controversy erupted in the 1860s and reforms were made.

There is also criticism regarding the prevalent gender gap in patents. Although historical laws that precluded women from obtaining patents are no longer in force, the number of women patent holders is still significantly disproportionate in comparison to their male counterparts.

See also

* History of copyright law *History of United States patent law

The history of United States patent law started even before the U.S. Constitution was adopted, with some state-specific patent laws. The history spans over more than three centuries.

Background

The oldest form of a patent was seen in Medieval ...

*United States patent case law

This is a list of notable patent law cases in the United States in chronological order. The cases have been decided notably by the United States Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) or the Board of Pat ...

*Scire facias

In English law, a writ of ''scire facias'' (Latin, meaning literally "make known") was a writ founded upon some judicial record directing the sheriff to make the record known to a specified party, and requiring the defendant to show cause why th ...

Notes

References

* Kenneth W. Dobyns, The Patent Office Pony; A History of the Early Patent Office, Sergeant Kirkland's Press 1994* Howard B. Rockman, Intellectual Property law for Engineers and Scientists. * Bugbee, Bruce W. Genesis of American Patent and Copyright Law. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press (1967). * Christine MacLeod, Inventing the Industrial Revolution: The English patent system, 1660–1800, Cambridge University Press. * Galvez-Behar, G

La République des inventeurs. Propriété et organisation de l'innovation en France

Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2008.

External links

;First patents ''American'' *X Series : "''Improvements in making pot ash and pearle ash''" *1st Numerical : "''Traction Wheel''" *1st Design : Script font type *1st Reissued : "''Grain Drill''" ;WebsitesAn Economic History of Patent Institutions

French Patent History

Patents Research Guide (Australian)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Patent Law History of patent law,

Patent law

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

Italian inventions

Patent law