History of libraries on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of

The first libraries consisted of

The first libraries consisted of

The

The

"Episode 1: The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean"

/ref> It flourished under the patronage of the

"The Great Library of Alexandria?"

. Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010 An early organization system was in effect at Alexandria. The In the West, the first public libraries were established under the

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the

During the Late Antiquity and Middle Ages periods, there was no Rome of the kind that ruled the Mediterranean for centuries and spawned the culture that produced twenty-eight public libraries in the ''urbs Roma''. The empire had been divided then later re-united again under

During the Late Antiquity and Middle Ages periods, there was no Rome of the kind that ruled the Mediterranean for centuries and spawned the culture that produced twenty-eight public libraries in the ''urbs Roma''. The empire had been divided then later re-united again under

In the

In the

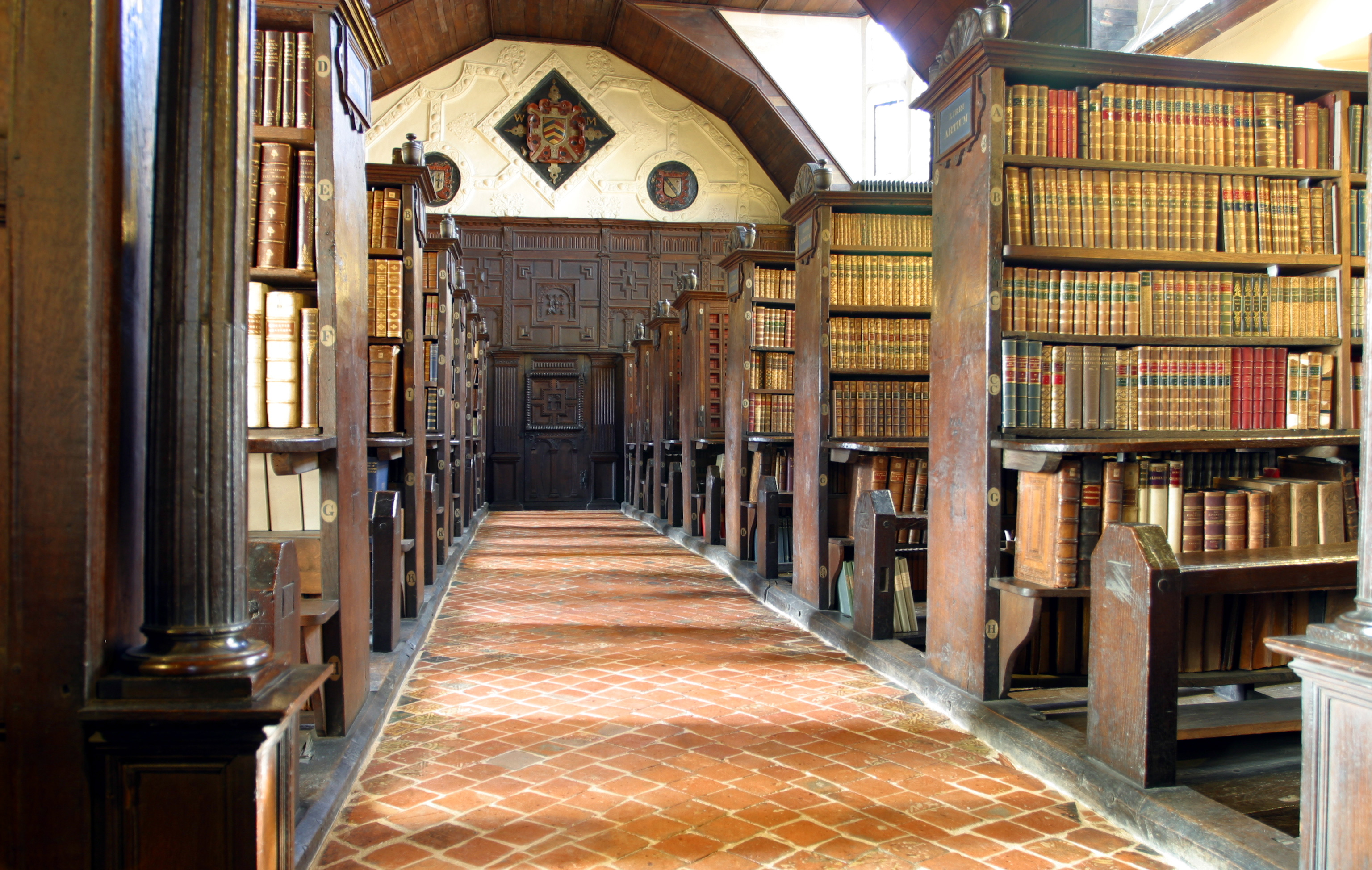

From the 15th century in central and northern Italy, libraries of

From the 15th century in central and northern Italy, libraries of  The Hungarian

The Hungarian

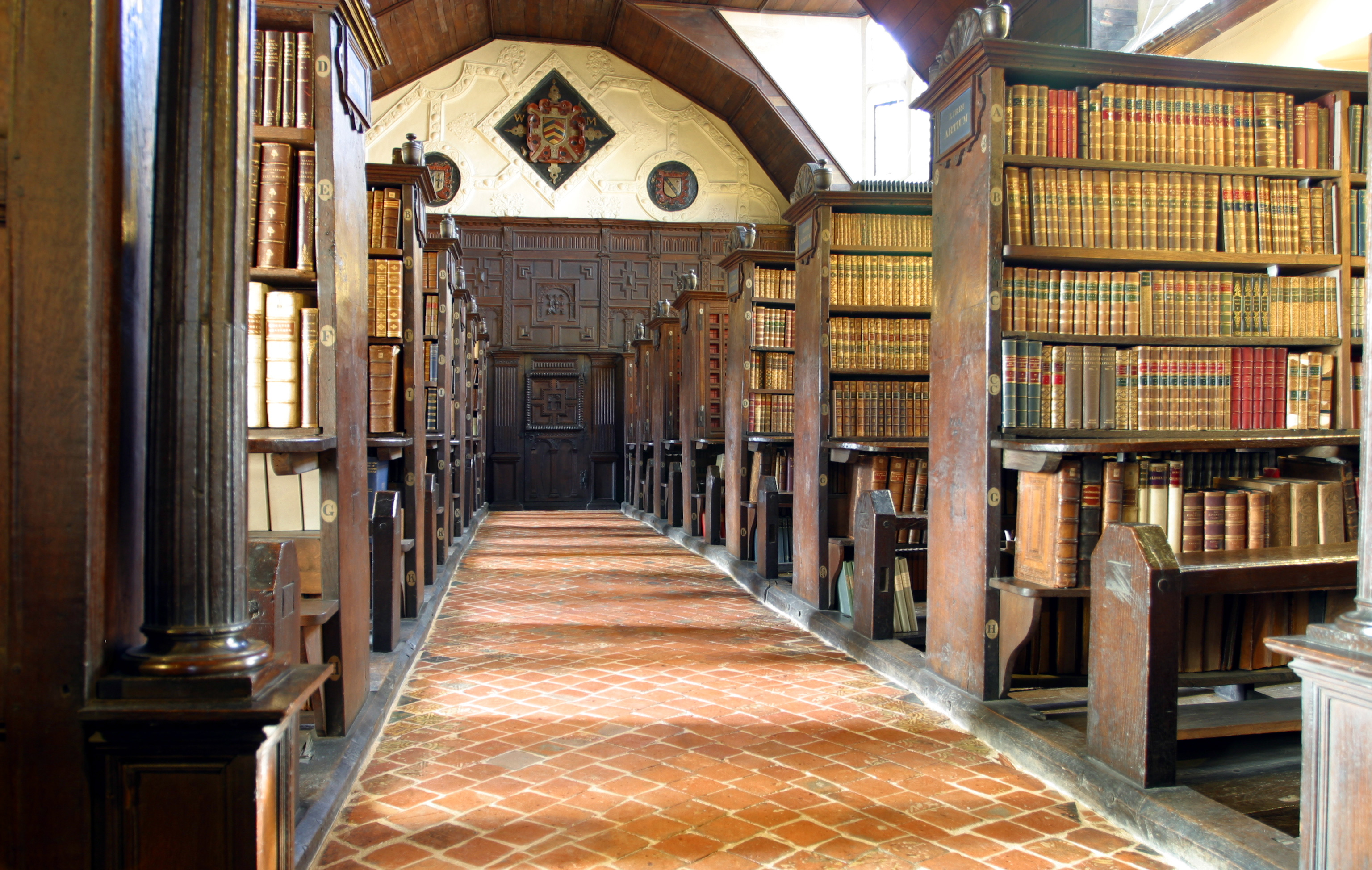

The 17th and 18th centuries include what is known as a golden age of libraries; during this some of the more important libraries were founded in Europe.

The 17th and 18th centuries include what is known as a golden age of libraries; during this some of the more important libraries were founded in Europe.  Even though the

Even though the

Private subscription libraries functioned much like commercial subscription libraries, with some variations. One of the most popular versions of the private subscription library was the gentlemen only library. Membership was restricted to the proprietors or shareholders, and ranged from a dozen or two to between four and five hundred.

The Liverpool Subscription library was a gentlemen only library. In 1798, it was renamed the Athenaeum when it was rebuilt with a newsroom and coffeehouse. It had an entrance fee of one guinea and an annual subscription of five shillings. An analysis of the registers for the first twelve years provides glimpses of middle-class reading habits in a mercantile community at this period. The largest and most popular sections of the library were history, antiquities, and geography, with 283 titles and 6,121 borrowings, and

Private subscription libraries functioned much like commercial subscription libraries, with some variations. One of the most popular versions of the private subscription library was the gentlemen only library. Membership was restricted to the proprietors or shareholders, and ranged from a dozen or two to between four and five hundred.

The Liverpool Subscription library was a gentlemen only library. In 1798, it was renamed the Athenaeum when it was rebuilt with a newsroom and coffeehouse. It had an entrance fee of one guinea and an annual subscription of five shillings. An analysis of the registers for the first twelve years provides glimpses of middle-class reading habits in a mercantile community at this period. The largest and most popular sections of the library were history, antiquities, and geography, with 283 titles and 6,121 borrowings, and

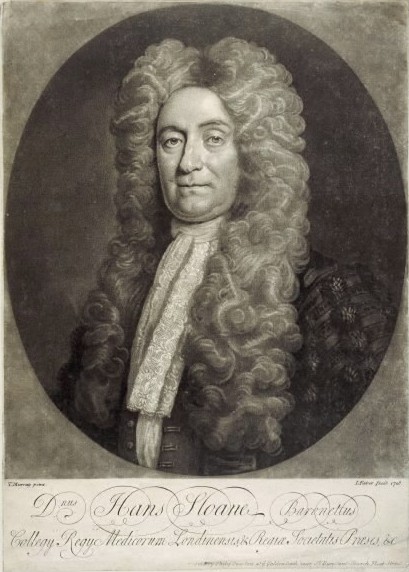

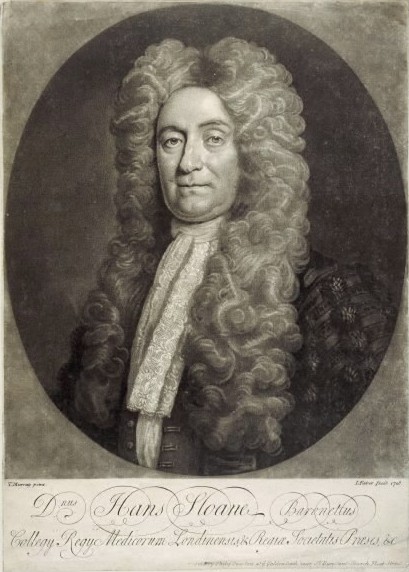

The first true national library was founded in 1753 as part of the

The first true national library was founded in 1753 as part of the  In France, the first national library was the

In France, the first national library was the

The

The

Although by the mid-19th century England could claim 274 subscription libraries and Scotland, 266, the foundation of the modern public library system in Britain is the

Although by the mid-19th century England could claim 274 subscription libraries and Scotland, 266, the foundation of the modern public library system in Britain is the  The advocacy of Ewart and Brotherton then succeeded in having a select committee set up to consider public library provision. The Report argued that the provision of public libraries would steer people towards temperate and moderate habits. With a view to maximising the potential of current facilities, the Committee made two significant recommendations. They suggested that the government should issue grants to aid the foundation of libraries and that the Museums Act 1845 should be amended and extended to allow for a tax to be levied for the establishment of public libraries. The Bill passed through

The advocacy of Ewart and Brotherton then succeeded in having a select committee set up to consider public library provision. The Report argued that the provision of public libraries would steer people towards temperate and moderate habits. With a view to maximising the potential of current facilities, the Committee made two significant recommendations. They suggested that the government should issue grants to aid the foundation of libraries and that the Museums Act 1845 should be amended and extended to allow for a tax to be levied for the establishment of public libraries. The Bill passed through

/ref> The original collection was bought by Reverend Abbot and the library trustees and was housed in Smith & Thompson's general store, which also acted as a post office. The New Hampshire State Legislature was encouraged by the innovation of Abbot and in 1849 became “the first state to pass a law authorizing towns to raise money to establish and maintain their own libraries”. By 1890 the library had outgrown its space and a new building was constructed. This building has been expanded twice since then to accommodate the growing collection. According to the Peterborough Town Library website, “its importance rests in its being created on the principle, accepted at Town Meeting, that the public library, like the public school, was deserving of maintenance by public taxation and should be owned and managed by the people of the community”. The American School Library (1839) was an early frontier traveling library in the United States. The year 1876 is key in the history of

The American School Library (1839) was an early frontier traveling library in the United States. The year 1876 is key in the history of

In the 20th century, many public libraries were built in different Modernist architecture styles, some more functional, others more representative. For many of these buildings, the quality of the interior spaces, their lighting and atmosphere, was becoming more significant than the façade design of the library building. Modernist architects like

In the 20th century, many public libraries were built in different Modernist architecture styles, some more functional, others more representative. For many of these buildings, the quality of the interior spaces, their lighting and atmosphere, was becoming more significant than the façade design of the library building. Modernist architects like

online edition

articles by scholars * Hoare, Peter, ed. (3 vol. 2006) ''The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland'', 2072 pages * Hobson, Anthony. ''Great Libraries'', Littlehampton Book Services (1970), surveys 27 famous European libraries (and 5 American ones) in 300pp * *Krummel, Donald William. 1999. ''Fiat lux, fiat latebra: a celebration of historical library functions.'' Champaign, Ill: Publications Office, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. * Lerner, Fred. (2nd ed. 2009) ''The Story of Libraries: From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age'', London, Bloomsbury * Martin, Lowell A. (1998) ''Enrichment: A History of the Public Library in the United States in the Twentieth Century'', Scarecow Press * Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009) ''The Library: An Illustrated History'', Skyhorse Publishing, New York, New York * * Staikos, Konstantinos, ''The History of the Library in Western Civilization'', translated by Timothy Cullen, New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press, 2004–2013 (six volumes). * , 1100pp; covers 122 major libraries in Europe, 59 in U.S, and 44 others, plus 47 thematic essays * * ; covers 60 major libraries

Hoyle, Alan (2020), "The Manchester Free Library Building, Home to the Spanish Instituto Cervantes"

**Krummel, D.W

Fiat lux, fiat latebra: a celebration of historical library functions.

Graduate School of Library and Information Science. University of Illinois. Occasional Paper 209.August 1999. {{Libraries and library science Library history

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of document

A document is a written, drawn, presented, or memorialized representation of thought, often the manifestation of non-fictional, as well as fictional, content. The word originates from the Latin ''Documentum'', which denotes a "teaching" or ...

s. Topics of interest include accessibility of the collection, acquisition of materials, arrangement and finding tools, the book trade, the influence of the physical properties of the different writing materials, language distribution, role in education, rates of literacy, budgets, staffing, libraries for targeted audiences, architectural merit, patterns of usage, and the role of libraries

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

in a nation's cultural heritage, and the role of government, church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

or private sponsorship. Computerization and digitization arose from the 1960s, and changed many aspects of libraries.

Library history

Library history is a subdiscipline within library science and library and information science focusing on the history of libraries and their role in societies and cultures. Some see the field as a subset of information history. Library history i ...

is the academic discipline

An academy ( Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy ...

devoted to the study of the history of libraries; it is a subfield of library science

Library science (often termed library studies, bibliothecography, and library economy) is an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary field that applies the practices, perspectives, and tools of management, information technology, education, and ...

and of history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

.

Early libraries

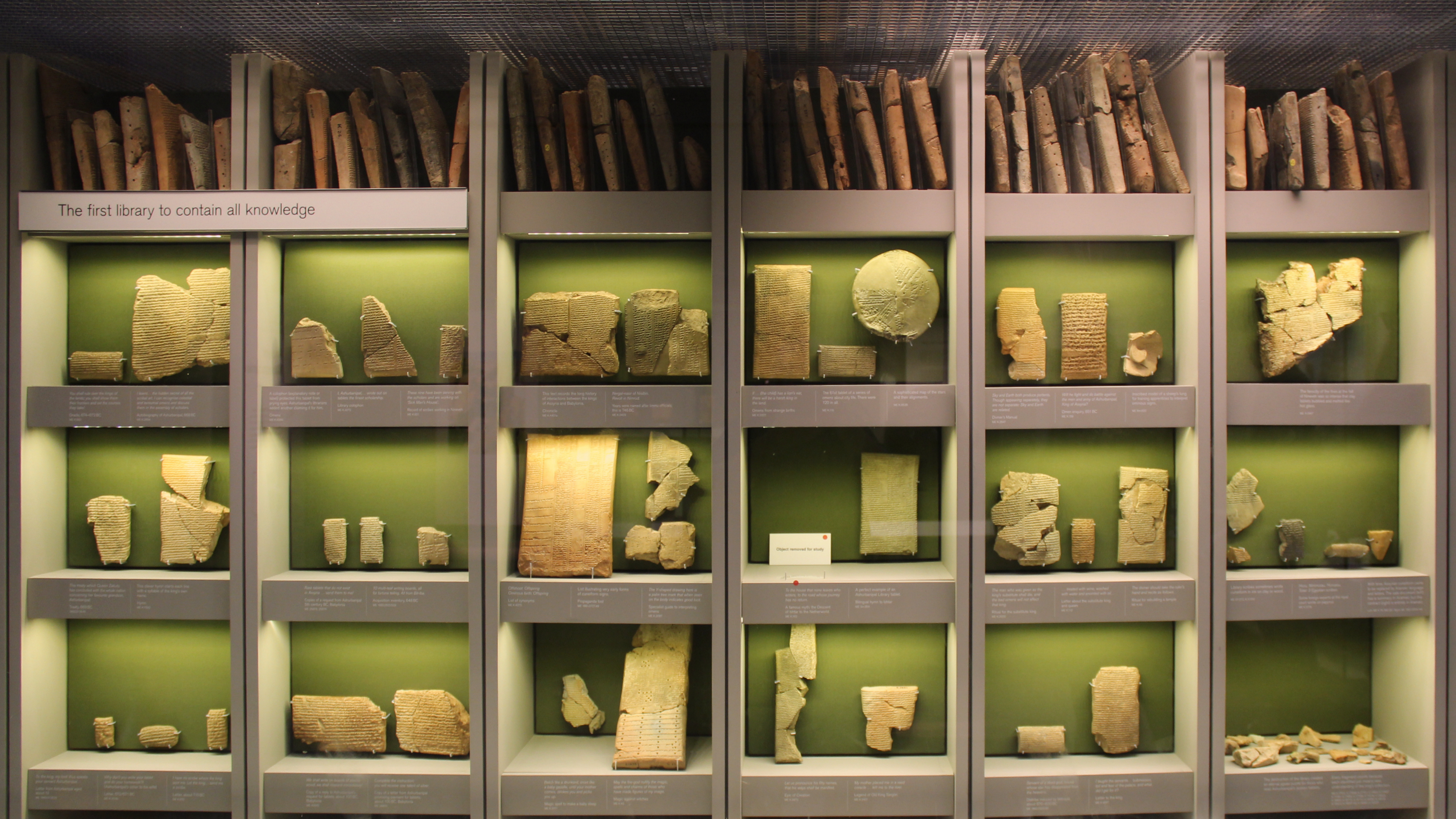

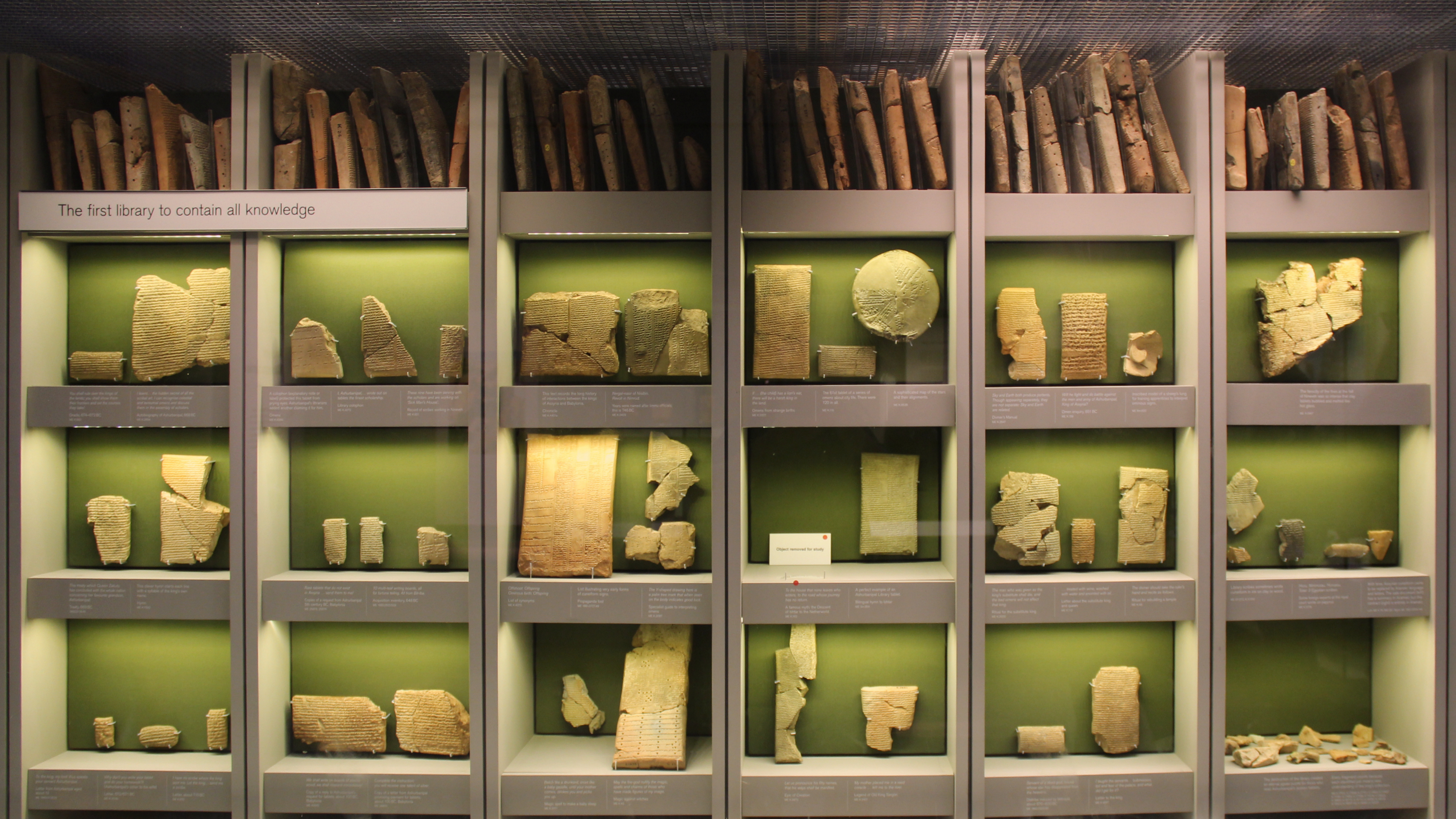

The first libraries consisted of

The first libraries consisted of archive

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or ...

s of the earliest form of writing – the clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylu ...

s in cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

discovered in temple rooms in Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of c ...

, some dating back to 2600 BC. About an inch thick, tablets came in various shapes and sizes. Mud-like clay was placed in the wooden frames, and the surface was smoothed for writing and allowed to dry until damp. After being inscribed, the clay dried in the sun or, for a harder finish, was baked in a kiln. For storage, tablets could be stacked on edge, side by side, the contents described by a title written on the edge that faced out and was readily seen. The first libraries appeared five thousand years ago in Southwest Asia's Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent ( ar, الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan, together with the northern region of Kuwait, southeastern region of ...

, an area that ran from Mesopotamia to the Nile in Africa. Known as the cradle of civilization, the Fertile Crescent was the birthplace of writing, sometime before 3000 BC. (Murray, Stuart A.P.) These archives, which mainly consisted of the records of commercial transactions or inventories, mark the end of prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

and the start of history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

.

Things were very similar in the government and temple records on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

of Ancient Egypt. The earliest discovered private archives were kept at Ugarit

)

, image =Ugarit Corbel.jpg

, image_size=300

, alt =

, caption = Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit

, map_type = Near East#Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size = 300

, relief=yes

, location = Latakia Governorate, Syria

, region = F ...

; besides correspondence and inventories, texts of myths may have been standardized practice-texts for teaching new scribes. There is also evidence of libraries at Nippur

Nippur (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logogram, logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. Akkadian language, Akkadian: '' ...

about 1900 BC and those at Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

about 700 BC showing a library classification

A library classification is a system of organization of knowledge by which library resources are arranged and ordered systematically. Library classifications are a notational system that represents the order of topics in the classification and al ...

system.

Over 30,000 clay tablets from the Library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BC, including texts in vari ...

have been discovered at Nineveh, providing modern scholars with a fantastic wealth of Mesopotamian literary, religious and administrative work. Among the findings were the Enuma Elish, also known as the ''Epic of Creation'', which depicts a traditional Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

n view of creation, the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh ...

'', a large selection of "omen texts" including ''Enuma Anu Enlil'' which "contained omens dealing with the moon, its visibility, eclipses, and conjunction with planets and fixed stars, the sun, its corona, spots, and eclipses, the weather, namely lightning, thunder, and clouds, and the planets and their visibility, appearance, and stations," and astronomic/astrological texts, as well as standard lists used by scribes and scholars such as word lists, bilingual vocabularies, lists of signs and synonyms, and lists of medical diagnoses.

The tablets were stored in various containers, such as wooden boxes, woven baskets of reeds, or clay shelves. The "libraries" were cataloged using colophons, which are a publisher's imprint on the spine of a book, or in this case, a tablet. The colophons stated the series name, the title of the tablet, and any extra information the scribe needed to indicate. Eventually, the clay tablets were organized by subject and size. Unfortunately, due to limited bookshelf space, older tablets were removed, which is why some were missing from the excavated cities in Mesopotamia.

According to legend, mythical philosopher Laozi

Laozi (), also known by numerous other names, was a semilegendary ancient Chinese Taoist philosopher. Laozi ( zh, ) is a Chinese honorific, generally translated as "the Old Master". Traditional accounts say he was born as in the state

...

was the keeper of books in the earliest library in China, which belonged to the Imperial Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by th ...

.Mukherjee, A. K. (1966). ''Librarianship: Its Philosophy and History''. Asia Publishing House. p. 86 Also, evidence of catalogs found in some destroyed ancient libraries illustrates the presence of librarians.

Classical period

Persia at the time of theAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

(550–330 BC) was home to some outstanding libraries that were serving two main functions: keeping the records of administrative documents e.g. transactions, governmental orders, and budget allocation within and between the Satrapies

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with con ...

and the central ruling State. And collection of resources on different sets of principles e.g. medical science, astronomy, history, geometry and philosophy.

In 1933 University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

excavated an impressive collection of clay tablets in Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

that indicated the Achaemenids' mastery of recording, classifying and storing a broad range of data. This archive is believed to be an administrative backbone of their ruling system throughout the vast territory of Persia. The baked tablets are written in three main languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian. The cuneiform texts cover various contents from records of sales, taxes, payments, treasury details and food storage to remarkable social, artistic and philosophical aspects of an ordinary life in the Empire. This priceless collection of tablets, known as the Persepolis Fortification Archive

The Persepolis Fortification Archive and Persepolis Treasury Archive are two groups of clay administrative archives — sets of records physically stored together – found in Persepolis dating to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The discover ...

, is property of Iran. A part of this impressive library archive is now kept in Iran while a major proportion is still in the hands of Chicago Oriental Institute as a long-term loan for the purpose of studying, analyzing and translating.

Some scholars believed that massive resources of archives and resources in different streams of science were transferred from Persia's main libraries to Egypt upon the conquest of Alexander III of Macedon

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to t ...

. The materials later translated into Latin, Egyptian, Coptic and Greek and shaped a remarkable body of science in the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

. The rest is said to have been set on fire and burnt by the Alexander militants..

Less historically tested claims have also reported a sizeable building in Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

, Jey, named Sarouyeh, which was being used by Iran's ancient dynasties to store collections of precious books and manuscripts. At least three Islamic scholars, al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

, Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi

Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar (also ''Albusar'', ''Albuxar''; full name ''Abū Maʿshar Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Balkhī'' ;

, AH 171–272), was an early Persian Muslim astrologer, thought to be the greatest ast ...

, and Hamza al-Isfahani

Hamza ibn al-Hasan bnal-Mu'addib al-Isfahani ( ar, حمزه الاصفهانی; – after 961), commonly known as Hamza al-Isfahani (or Hamza Isfahani; ) was a Persian philologist and historian, who wrote in Arabic during the Buyid era. A Persia ...

, have named this hidden library in their works. The same references claimed that this treasury discovered in the early Islam and the valuable books were selected, baled and transferred to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

for later reading and translating. As reported by observers, at the time of unearthing the archive, the manuscripts' alphabet was entirely unknown to the ordinary people.

The

The Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

, in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, was the largest and most significant great library of the ancient world.Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, Sagan, C 1980"Episode 1: The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean"

/ref> It flourished under the patronage of the

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; grc, Πτολεμαῖοι, ''Ptolemaioi''), sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty (Λαγίδαι, ''Lagidae;'' after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic ...

and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library was conceived and opened either during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

(323–283 BC) or during the reign of his son Ptolemy II (283–246 BC).Phillips, Heather A."The Great Library of Alexandria?"

. Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010 An early organization system was in effect at Alexandria. The

Library of Celsus

The Library of Celsus ( el, Βιβλιοθήκη του Κέλσου) is an ancient Roman building in Ephesus, Anatolia, now part of Selçuk, Turkey. The building was commissioned in the 110s A.D. by a consul, Gaius Julius Aquila, as a funerary ...

in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, now part of Selçuk, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

was built in honor of the Roman Senator

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (completed in AD 135) by Celsus' son, Tiberius Julius Aquila Polemaeanus (consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

, 110). The library was built to store 12,000 scroll

A scroll (from the Old French ''escroe'' or ''escroue''), also known as a roll, is a roll of papyrus, parchment, or paper containing writing.

Structure

A scroll is usually partitioned into pages, which are sometimes separate sheets of papyrus ...

s and to serve as a monumental tomb for Celsus. The library's ruins were hidden under debris of the city of Ephesus that was deserted in early Middle Ages. In 1903, Austrian excavations led to this hidden heap of rubble that had collapsed during an earthquake. The donator's son built the library to honor his father's memory and construction began around 113 or 114. Presently, visitors only see the remains of the library's facade.

Private or personal libraries made up of written books (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. The celebrated book collectors of Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

Antiquity were listed in the late 2nd century in ''Deipnosophistae

The ''Deipnosophistae'' is an early 3rd-century AD Greek work ( grc, Δειπνοσοφισταί, ''Deipnosophistaí'', lit. "The Dinner Sophists/Philosophers/Experts") by the Greek author Athenaeus of Naucratis. It is a long work of liter ...

''. All these libraries were Greek; the cultivated Hellenized diners in ''Deipnosophistae'' pass over the libraries of Rome in silence. By the time of Augustus there were public libraries near the forums of Rome: there were libraries in the Porticus Octaviae

The Porticus Octaviae (Portico of Octavia; it, Portico di Ottavia) is an ancient structure in Rome. The colonnaded walks of the portico enclosed the temples of Jupiter Stator and Juno Regina, as well as a library. The structure was used as a fi ...

near the Theatre of Marcellus

The Theatre of Marcellus ( la, Theatrum Marcelli, it, Teatro di Marcello) is an ancient open-air theatre in Rome, Italy, built in the closing years of the Roman Republic. At the theatre, locals and visitors alike were able to watch performances o ...

, in the temple of Apollo Palatinus, and in the Ulpian Library in the Forum of Trajan

Trajan's Forum ( la, Forum Traiani; it, Foro di Traiano) was the last of the Imperial fora to be constructed in ancient Rome. The architect Apollodorus of Damascus oversaw its construction.

History

This forum was built on the order of the empe ...

. The state archives were kept in a structure on the slope between the Roman Forum

The Roman Forum, also known by its Latin name Forum Romanum ( it, Foro Romano), is a rectangular forum (plaza) surrounded by the ruins of several important ancient government buildings at the center of the city of Rome. Citizens of the ancient ...

and the Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; it, Campidoglio ; la, Mons Capitolinus ), between the Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn. Th ...

.

Private libraries

A private library is a library that is privately owned. Private libraries are usually intended for the use of a small number of people, or even a single person. As with public libraries, some people use bookplates – stamps, stickers or ...

appeared during the late republic: Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

inveighed against libraries fitted out for show by illiterate owners who scarcely read their titles in the course of a lifetime, but displayed the scrolls in bookcases (''armaria'') of citrus wood inlaid with ivory that ran right to the ceiling: "by now, like bathrooms and hot water, a library is got up as standard equipment for a fine house (''domus

In Ancient Rome, the ''domus'' (plural ''domūs'', genitive ''domūs'' or ''domī'') was the type of town house occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It was found in almost all the ma ...

''). Libraries were amenities suited to a villa, such as Cicero's at Tusculum, Maecenas

Gaius Cilnius Maecenas ( – 8 BC) was a friend and political advisor to Octavian (who later reigned as emperor Augustus). He was also an important patron for the new generation of Augustan poets, including both Horace and Virgil. During the rei ...

's several villas, or Pliny the Younger's, all described in surviving letters. At the Villa of the Papyri

The Villa of the Papyri ( it, Villa dei Papiri, also known as ''Villa dei Pisoni'' and in early excavation records as the ''Villa Suburbana'') was an ancient Roman villa in Herculaneum, in what is now Ercolano, southern Italy. It is named after ...

at Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

, apparently the villa of Caesar's father-in-law, the Greek library has been partly preserved in volcanic ash; archaeologists speculate that a Latin library, kept separate from the Greek one, may await discovery at the site.

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

as each succeeding emperor strove to open one or many which outshone that of his predecessor. Rome's first public library was established by Asinius Pollio. Pollio was a lieutenant of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

and one of his most ardent supporters. After his military victory in Illyria, Pollio felt he had enough fame and fortune to create what Julius Caesar had sought for a long time: a public library to increase the prestige of Rome and rival the one in Alexandria. Pollios's library, the ''Anla Libertatis'', which was housed in the ''Atrium Libertatis'', was centrally located near the Forum Romanum. It was the first to employ an architectural design that separated works into Greek and Latin. All subsequent Roman public libraries will have this design. At the conclusion of Rome's civil wars following the death of Marcus Antonius

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

in 30 BC, the Emperor Augustus sought to reconstruct many of Rome's damaged buildings. During this construction, Augustus created two more public libraries. The first was the library of the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine, often called the Palatine library

The Bibliotheca Palatina ("Electoral Palatinate, Palatinate library") of Heidelberg was the most important library of the German Renaissance, numbering approximately 5,000 printed books and 3,524 manuscripts. The Bibliotheca was a prominent pri ...

, and the second was the library of the ''Porticus Octaviae'', although there is some debate that the ''Porticus'' library was actually built by Octavia. Unfortunately, the library of the ''Porticus Octaviae'' would be later destroyed in the disastrous fire of Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

that broke out in AD 80.

Two more libraries were added by the Emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

on Palatine Hill and one by Vespasian after 70. Vespasian's library was constructed in the Forum of Vespasian, also known as the ''Forum of Peace'', and became one of Rome's principal libraries. The ''Bibliotheca Pacis'' was built along the traditional model and had two large halls with rooms for Greek and Latin libraries containing the works of Galen and Lucius Aelius. One of the best preserved was the ancient Ulpian Library built by the Emperor Trajan. Completed in 112/113 AD, the Ulpian Library

The Bibliotheca Ulpia ("Ulpian Library") was a Roman library founded by the Emperor Trajan in AD 114 in his forum, the Forum of Trajan, located in ancient Rome. It was considered one of the most prominent and famous libraries of antiquity and beca ...

was part of Trajan's Forum built on the Capitoline Hill. Trajan's Column separated the Greek and Latin rooms which faced each other. The structure was approximately fifty feet high with the peak of the roof reaching almost seventy feet.

Unlike the Greek libraries, readers had direct access to the scrolls, which were kept on shelves built into the walls of a large room. Reading or copying was normally done in the room itself. The surviving records give only a few instances of lending features. Most of the large Roman baths were also cultural centres, built from the start with a library, a two-room arrangement with one room for Greek and one for Latin texts.

Libraries were filled with parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins of ...

scrolls

A scroll (from the Old French ''escroe'' or ''escroue''), also known as a roll, is a roll of papyrus, parchment, or paper containing writing.

Structure

A scroll is usually partitioned into pages, which are sometimes separate sheets of papyrus ...

as at Library of Pergamum

The Library of Pergamum in Pergamum, Asia Minor or Anatolia (present day Turkey). It was one of the most important libraries in the ancient world.

The city of Pergamum

Founded sometime during 3rd century BC, during the Hellenistic Age, Perga ...

and on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

scrolls as at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

: the export of prepared writing materials was a staple of commerce. There were a few institutional or royal libraries which were open to an educated public (such as the Serapeum collection of the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

, once the largest library in the ancient world), but on the whole collections were private. In those rare cases where it was possible for a scholar to consult library books there seems to have been no direct access to the stacks. In all recorded cases the books were kept in a relatively small room where the staff went to get them for the readers, who had to consult them in an adjoining hall or covered walkway. Most of the works in catalogs were of a religious nature, such as volumes of the Bible or religious service books. "In a number of cases the library was entirely theological and liturgical, and in the greater part of the libraries the non-ecclesiastical content did not reach one third of the total"Beddie, J. (1930). The Ancient Classics in the Mediaeval Libraries. ''Speculum'', 5(1), 3–20. In addition to these types of works, in some libraries during that time Plato was especially popular. In the early Middle Ages, Aristotle was more popular. Additionally, there was quite a bit of censoring within libraries of the time; many works that were "scientific and metaphysical" were not included in the majority of libraries during that time period. Latin authors were better represented within library holdings and Roman works were less represented. Cicero was also an especially popular author along with the histories of Sallust. Additionally, Virgil was universally represented at most of the medieval libraries of the time. One of the most popular was Ovid, mentioned by approximately twenty French catalogues and nearly thirty German ones. Surprisingly, old Roman textbooks on grammar were still being used at that time.

In 213 BC during the reign of Emperor Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

most books were ordered destroyed. The Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(202 BC – 220 AD) reversed this policy for replacement copies, and created three imperial libraries. Liu Xin a curator of the imperial library was the first to establish a library classification

A library classification is a system of organization of knowledge by which library resources are arranged and ordered systematically. Library classifications are a notational system that represents the order of topics in the classification and al ...

system and the first book notation system. At this time the library catalog

A library catalog (or library catalogue in British English) is a register of all bibliographic items found in a library or group of libraries, such as a network of libraries at several locations. A catalog for a group of libraries is also c ...

was written on scrolls of fine silk and stored in silk bags. Important new technological innovations include the use of paper and block printing. Wood-block printing, facilitated the large-scale reproduction of classic Buddhist texts which were avidly collected in many private libraries that flourished during the T'ang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingd ...

(618–906 AD).

The Ming Dynasty in 1407 founded the imperial library, the Wen Yuan Pavilion. It also sponsored the massive compilation of the Yongle Encyclopedia

The ''Yongle Encyclopedia'' () or ''Yongle Dadian'' () is a largely-lost Chinese ''leishu'' encyclopedia commissioned by the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1403 and completed by 1408. It comprised 22,937 manuscript rolls or chapters, in 1 ...

, containing 11,000 volumes including copies of over 7000 books. It was soon destroyed, but similar very large compilations appeared in 1725 and 1772.

Late antiquity

In Persia, collection of books once again attracted both rulers and priests throughout theSassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

(224 - 651 AD) once the country could gain a relatively political and economic stability. Priests intended to compile the existing Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion and one of the world's History of religion, oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian peoples, Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a Dualism in cosmology, du ...

manuscripts from all over the territory and rulers were keen on the consolidation and promotion of science. At the time, many Zoroastrian fire temples were co-located with local libraries that were designed to collect and promote the religious contents. Academy of Gundeshapur

Gundeshapur ( pal, 𐭥𐭧𐭩𐭠𐭭𐭣𐭩𐭥𐭪𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, ''Weh-Andiōk-Šābuhr''; New Persian: , ''Gondēshāpūr'') was the intellectual centre of the Sassanid Empire and the home of the Academy of Gundishapur, founde ...

being built by Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩, Šābuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

can well-represents the Sasanid Kings willingness for collection and consolidation of science resources. The Academy comprised an extensive library, a hospital and an academy. Enriching the library resources, the Academy constantly was sending ambassadors to widespread geographical regions e.g. China, Rome and India to inscribe the manuscripts, codices, and books; translate them to Pahlavi from diverse languages e.g. Sanskrit, Greek and Syriac and bring them back to the Centre.

During the Late Antiquity and Middle Ages periods, there was no Rome of the kind that ruled the Mediterranean for centuries and spawned the culture that produced twenty-eight public libraries in the ''urbs Roma''. The empire had been divided then later re-united again under

During the Late Antiquity and Middle Ages periods, there was no Rome of the kind that ruled the Mediterranean for centuries and spawned the culture that produced twenty-eight public libraries in the ''urbs Roma''. The empire had been divided then later re-united again under Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

who moved the capital of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

in 330 AD to the city of Byzantium which was renamed Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The Roman intellectual culture that flourished in ancient times was undergoing a transformation as the academic world moved from laymen to Christian clergy. As the West crumbled, books and libraries flourished and flowed east toward the Byzantine Empire. There, four different types of libraries were established: imperial, patriarchal, monastic, and private. Each had its own purpose and, as a result, their survival varied.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

was a new force in Europe and many of the faithful saw Hellenistic culture as pagan. As such, many classical Greek works, written on scrolls, were left to decay as only Christian texts were thought fit for preservation in a codex, the progenitor of the modern book. In the East, however, this was not the case as many of these classical Greek and Roman texts were copied. " rmerly paper was rare and expensive, so every spare page of available books was pressed into use. Thus a seventeenth-century edition of the Ignatian epistles, in Mar Saba, had copied onto its last pages, probably in the early eighteenth century, a passage allegedly from the letters of Clement of Alexandria". Old manuscripts were also used to bind new books because of the costs associated with paper and also because of the scarcity of new paper.

In Byzantium, much of this work devoted to preserving Hellenistic thought in codex form was performed in scriptoriums by monks. While monastic library scriptoriums flourished throughout the East and West, the rules governing them were generally the same. Barren and sun-lit rooms (because candles were a source of fire) were major features of the scriptorium that was both a model of production and monastic piety. Monks scribbled away for hours a day, interrupted only by meals and prayers. With such production, medieval monasteries began to accumulate large libraries. These libraries were devoted solely to the education of the monks and were seen as essential to their spiritual development. Although most of these texts that were produced were Christian in nature, many monastic leaders saw common virtues in the Greek classics. As a result, many of these Greek works were copied, and thus saved, in monastic scriptoriums.

When Europe passed into the Dark Ages, Byzantine scriptoriums laboriously preserved Greco-Roman classics. As a result, Byzantium revived Classical models of education and libraries. The Imperial Library of Constantinople

The Imperial Library of Constantinople, in the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, was the last of the great libraries of the ancient world. Long after the destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria and the other ancient libraries, it prese ...

was an important depository of ancient knowledge. Constantine himself wanted such a library but his short rule denied him the ability to see his vision to fruition. His son Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germani ...

made this dream a reality and created an imperial library in a portico of the royal palace. He ruled for 24 years and accelerated the development of the library and the intellectual culture that came with such a vast accumulation of books.

Constantius II appointed Themistius

Themistius ( grc-gre, Θεμίστιος ; 317 – c. 388 AD), nicknamed Euphrades, (eloquent), was a statesman, rhetorician, and philosopher. He flourished in the reigns of Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valens, Gratian, and Theodosius I; and ...

, a pagan philosopher and teacher, as chief architect of this library building program. Themistius set about a bold program to create an imperial public library that would be the centerpiece of the new intellectual capital of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Classical authors such as Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prow ...

, Isocrates

Isocrates (; grc, Ἰσοκράτης ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education throu ...

, Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

, Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, and Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

were sought. Themeistius hired calligraphers and craftsman to produce the actual codices. He also appointed educators and created a university-like school centered around the library.

After the death of Constantius II, Julian the Apostate

Julian ( la, Flavius Claudius Julianus; grc-gre, Ἰουλιανός ; 331 – 26 June 363) was Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplato ...

, a bibliophile intellectual, ruled briefly for less than three years. Despite this, he had a profound impact on the imperial library and sought both Christian and pagan books for its collections. Later, the Emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

hired Greek and Latin scribes full-time with from the royal treasury to copy and repair manuscripts.

At its height in the 5th century, the Imperial Library of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

had 120,000 volumes and was the largest library in Europe. A fire in 477 consumed the entire library but it was rebuilt only to be burned again in 726, 1204, and in 1453 when Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks.

Patriarchal libraries fared no better, and sometimes worse, than the Imperial Library. The Library of the Patriarchate of Constantinople was founded most likely during the reign of Constantine the Great in the 4th century. As a theological library, it was known to have employed a library classification

A library classification is a system of organization of knowledge by which library resources are arranged and ordered systematically. Library classifications are a notational system that represents the order of topics in the classification and al ...

system. It also served as a repository of several ecumenical councils

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

such as the Council of Nicea, Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church th ...

, and the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

. The library, which employed a librarian and assistants, may have been originally located in the Patriarch's official residence before it was moved to the Thomaites Triclinus in the 7th century. While much is not known about the actual library itself, it is known that many of its contents were subject to destruction as religious in-fighting ultimately resulted in book burnings

Book burning is the deliberate destruction by fire of books or other written materials, usually carried out in a public context. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or politi ...

.

During this period, small private libraries existed. Many of these were owned by church members and the aristocracy. Teachers also were known to have small personal libraries as well as wealthy bibliophiles who could afford the highly ornate books of the period.

Thus, in the 6th century, at the close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

, minister to Theodoric, established a monastery at Vivarium in the toe of Italy (modern Calabria) with a library where he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus not only collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of reading and methods for copying texts accurately. In the end, however, the library at Vivarium was dispersed and lost within a century.

Through Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

and especially the scholarly presbyter Pamphilus of Caesarea

Saint Pamphilus ( el, Πάμφιλος; latter half of the 3rd century – February 16, 309 AD), was a presbyter of Caesarea and chief among the biblical scholars of his generation. He was the friend and teacher of Eusebius of Caesarea, who ...

, an avid collector of books of Scripture, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory Nazianzus

Gregory of Nazianzus ( el, Γρηγόριος ὁ Ναζιανζηνός, ''Grēgorios ho Nazianzēnos''; ''Liturgy of the Hours'' Volume I, Proper of Saints, 2 January. – 25 January 390,), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory N ...

, Basil the Great

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Ca ...

, Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

and others came and studied there.

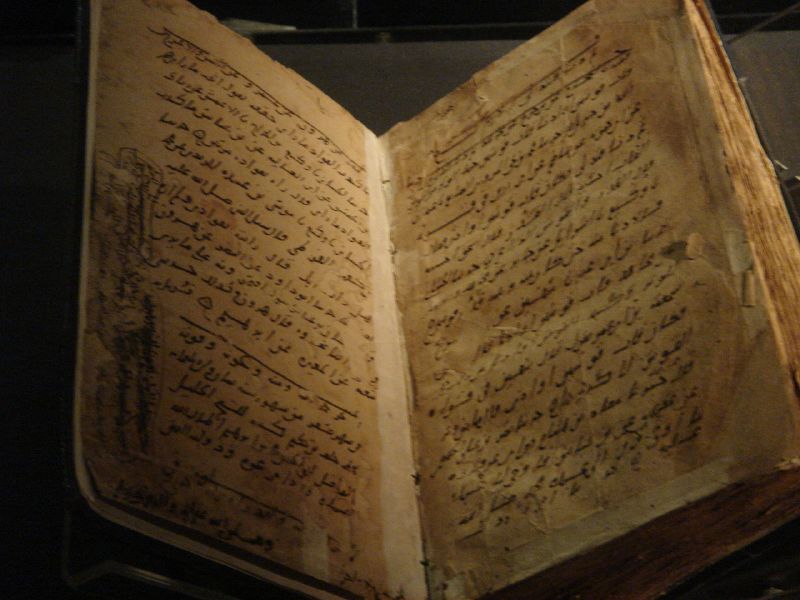

Islamic intervention

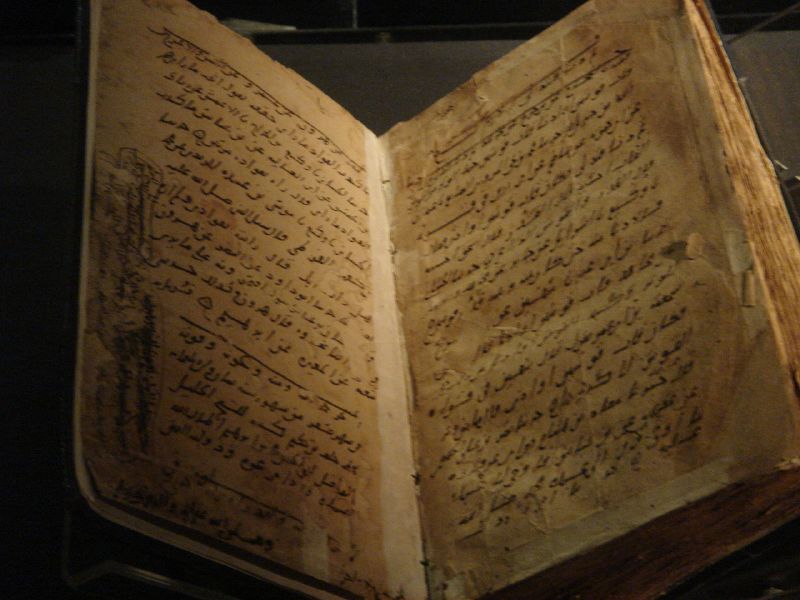

Inside a Qur'anic library in Chinguetti, Mauritania The need for the preservation of theQuran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

and the Traditions of Muhammad is what primarily inspired Muslims to develop collections of writings. Mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

s that were playing a central role in Muslims' day-to-day life gradually welcomed incorporated libraries that stored and preserved all types of knowledge, from devotional books like Quran to books on philosophy, geography and science.

The centrality of the Qurʾān

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God in Islam, God. It is organized in 114 surah, cha ...

as the prototype of the written word in Islam bears significantly on the role of books within its intellectual tradition and educational system. An early impulse in Islam was to manage reports of events, key figures and their sayings and actions. Thus, "the onus of being the last 'People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

' engendered an ethos of librarianship" early on and the establishment of important book repositories throughout the Muslim world have occurred ever since.

By the 8th century China's art of papermaking was acquired by Iranians and then developed across the whole Muslim world. From the art, Muslims developed papermaking into an industry. As a result of this technical enhancement, the books were more easily manufactured and they were more broadly accessible. Coincided with the encouragement of science and a breakthrough in the translation movement, public and private libraries started to boost all around Islamic lands. "libraries (royal, public, specialized, private) had become common and bookmen (authors, translators, copiers, illuminators, librarians, booksellers' collectors) from all classes and sections of society, of all nationalities and ethnic backgrounds, vied with each other in the production and distribution of books."

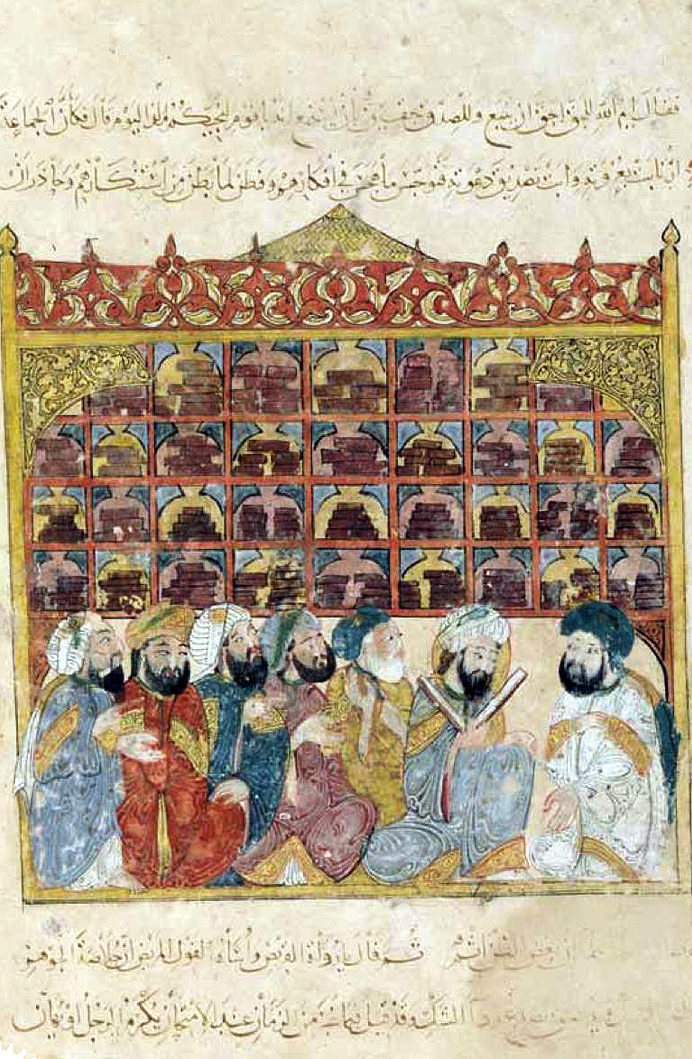

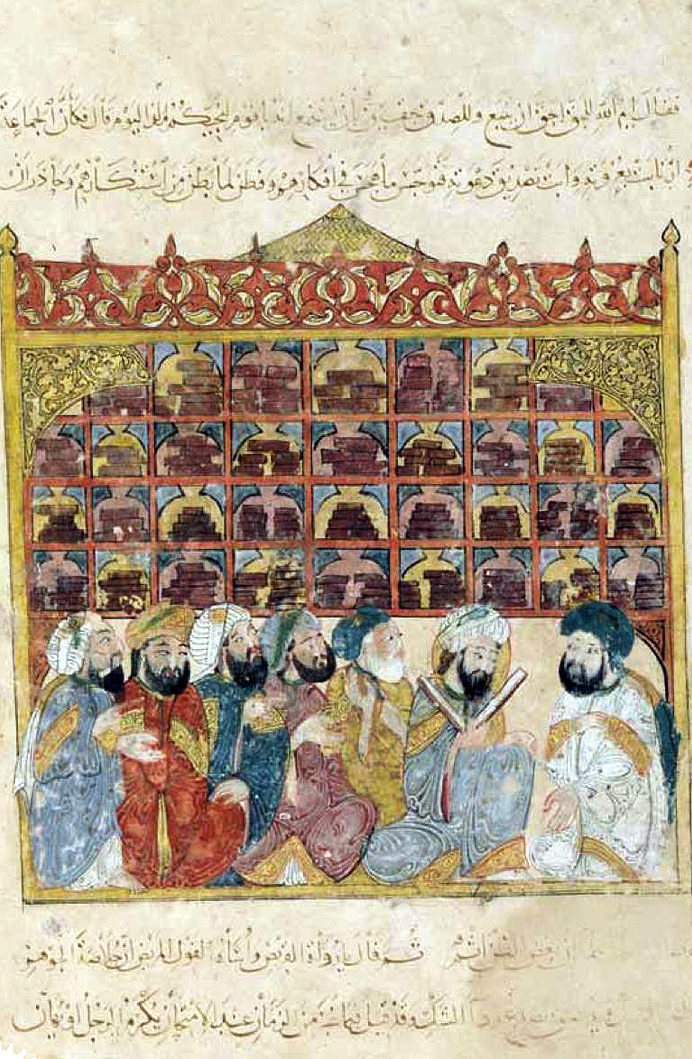

A series of outstanding libraries within the Islamic territories were founded and flourished alongside the Islam spread. Abbasid Caliphs

The Abbasid caliphs were the holders of the Islamic title of caliph who were members of the Abbasid dynasty, a branch of the Quraysh tribe descended from the uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib.

The family came t ...

were true patrons of learning and collection of ancient and contemporary literature. This genuine enthusiasm actualized as exceptionally fine royal libraries in Baghdad, a ruling heart of Islamic lands. The Caliphs' generous support for retrieving, copying and collecting the resources flourished all sorts of expertise associated with books. The emergence of theological schools, later on, multiplied the libraries. These schools that were called ''Dar al Ilm'', ''Madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

'' or ''House of Knowledge'' were each endowed by Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic sects with the purpose of representing their tenets as well as promoting the dissemination of knowledge. Rich libraries were inseparable components of 'Houses of knowledge'. The Nizamiyeh, founded by Nizam al Mulk

Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi (April 10, 1018 – October 14, 1092), better known by his honorific title of Nizam al-Mulk ( fa, , , Order of the Realm) was a Persian scholar, jurist, political philosopher and Vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising fr ...

, and Mustansiriyeh Madarsa, founded by al-Mustansir, were two most renowned and popular schools which attracted passionate students all across Muslim lands.

The Fatimids (r. 909-1171) and their successors at Alamut

Alamut ( fa, الموت) is a region in Iran including western and eastern parts in the western edge of the Alborz (Elburz) range, between the dry and barren plain of Qazvin in the south and the densely forested slopes of the Mazandaran provinc ...

also possessed many great libraries within their domains, attracting scholars from every creed and origin. The historian Ibn Abi Tayyi’ describes the Fatimid palace library, which probably contained the largest trove of literature on earth at the time, as a “wonder of the world”. Similarly, at the torching of the Alamut library, the conqueror Juwayni boasts that its fame “had spread throughout the world”.

Through these major knowledge expansion, libraries transformed into vibrant centers of the Islamic communities. These knowledge sharing centers were being attended constantly by varied patrons from mature scholars and enthusiastic students to poets and courtiers. Major libraries often employed translators and copyists in large numbers, in order to render into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

the bulk of the available Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Greek, Roman and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

non-fiction and the classics of literature. At the time libraries were the place that books and manuscripts were collected, read, copied, reproduced and borrowed by students, masters and even ordinary people. New resources could be acquired in a range of ways, with bequest, ''waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitabl ...

'', the major contributor. Based on this well-grounded tradition, many scholars and men of wealth bequeathed their book collections to the mosques, shrines, libraries and schools through which their private collection would be not only properly preserved but also made accessible to the whole community.

At the time even local rulers demonstrated their passion for knowledge by designing and developing public libraries that could stand out in both aesthetic features and creating a space that maximizes the patrons' comfort. Al-Maqdisi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

, a Muslim Geographer, once got stunned by stepping into one of these well-designed libraries in Shiraz

Shiraz (; fa, شیراز, Širâz ) is the List of largest cities of Iran, fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars province, Fars Province, which has been historically known as Pars (Sasanian province), Pars () and Persis. As o ...

:

''a complex of buildings surrounded by gardens with lakes and waterways. The buildings were topped with domes, and comprised an upper and a lower storey with a total, according to the chief official, of 360 rooms....In each department, catalogues were placed on a shelf... the rooms were furnished with

carpets...''

Though this flowering of Islamic learning ceased centuries later when learning began declining in the Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

, after many of these libraries were destroyed by Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire ( 1206- 1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

. Others were victim of wars and religious strife in the Islamic world. Many of those priceless manuscripts were transferred into European libraries and museums during the colonial period. However, a few examples of these medieval libraries, such as the libraries of Chinguetti

Chinguetti () ( ar, شنقيط, translit=Šinqīṭ) is a ksar and a medieval trading center in northern Mauritania, located on the Adrar Plateau east of Atar.

Founded in the 13th century as the center of several trans-Saharan trade routes, this ...

in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

, remain intact and relatively unchanged.

The contents of these Islamic libraries were copied by Christian monks in Muslim/Christian border areas, particularly Spain and Sicily. From there they eventually made their way into other parts of Christian Europe. These copies joined works that had been preserved directly by Christian monks from Greek and Roman originals, as well as copies Western Christian monks made of Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

works. The resulting conglomerate libraries are the basis of every modern library today.

Prominent libraries throughout the Islamic lands

* Bait al Hikma (House of Wisdom) or Khizana al Hikma (Treasury of Wisdom)- Baghdad -9th Century:Al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'mu ...

, the seventh Abbasid caliph founded a splendid science center consisting of an observatory for astrologists and a rich library with some very rare and precious resources. Many of those resources were on other and older cultures, thus far, translation was the cornerstone of the institution with professional translators working on Greek, Persian, Indian and Syriac materials.

* Yahya ibn Abi Mansur

Yahya ibn Abi Mansur ( ar, یحیی ابن ابی منصور), was a senior Persian official from the Banu al-Munajjim family, who served as an astronomer/astrologer at the court of Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun. His Persian name was Bizist, son of F ...

(Ibn Munajem) Library- 9th century: As a Khalifah's Chief Astrologer, he was the owner of a luxurious palace containing a tremendous library with numerous books in different sets of disciplines and science, in particular, astrology. This library was called “Treasury of Wisdom” or “Khazanah Al-Hekmah”.

* Nuh Ibn Mansour Samani Library- Bukhara-10th century: Samanid Empire rulers were famous for showing a considerable passion for culture and science and their consistent support for promoting libraries. Nuh II had a sizable library. Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

who was one of the visitors to Mansour's library in Bukhara has described it as extraordinary in terms of the number of volumes and the value of books. Looking for a certain item in medicine, he requested an entry permit from the Sultan to browse the library storage space. The book stack had been composed of plenty of rooms, each room had contained numerous boxes and each box had been filled with stacks of books as he reported.

* Baha al-Dowleh and Azod al-Dowleh Daylami Library-Shiraz- 10th century: These regional rulers from Iranian Daylamites Dynasty were owners of one of the most prominent libraries within the Islamic lands. As stated by al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

, a reputable Islamic historian and geographer, a copy of each and every book he had ever seen during his life and travels, all were presented in Azod al-Dowleh library.

al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

described the library as ''a complex of buildings surrounded by gardens with lakes and waterways. The buildings were topped with domes, and comprised an upper and a lower storey with a total, according to the chief official, of 360 rooms.... In each department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

, catalogues

Catalog or catalogue may refer to:

*Cataloging

**'emmy on the 'og

**in science and technology

*** Library catalog, a catalog of books and other media

****Union catalog, a combined library catalog describing the collections of a number of librarie ...

were placed on a shelf... the rooms were furnished with carpets''.

* The Library of Abu-Nasr Shapur Ibn Ardeshir- Baghdad- 10th century: Abu-Nasr who was a Daylamites’ Minister, founded a mega well-known public library in Baghdad that is claimed to hold 10 thousand volumes. The library was destroyed during Baghdad's big fire.

* Sahib ibn Abbad

Abu’l-Qāsim Ismāʿīl ibn-i ʿAbbād ibn-i ʿAbbās ( fa, ابوالقاسم اسماعیل بن عباد بن عباس; born 938 - died 30 March 995), better known as Ṣāḥib ibn-i ʿAbbād (), also known as Ṣāḥib (), was a Persian sc ...

Library- Rey- 10th century: The Iranian Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

to Buyid rulers established a legendary public library holding around 200,000 volumes. Ibn Abbad who was so proud of this great collection of books once refused the invitation of Samanid rulers to become their Grand Vizier in Bukhara, giving the excuse of attachment to his books that would need around 400 camels to carry on. The library was partially destroyed in 1029 by the troops of the Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

. As evidence to a large amount of the resources, some scholars claimed that just the library catalogue was equal to 10 volumes.

* Greater Merv or Merv Shahijan set of libraries: Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known fo ...

, a renowned Moslem bibliographer and geographer, on a way to his continual travels, stopped by Merv and settled there for a while to make the best use of sets of impressive libraries to complement his research studies. He named ten distinct exceptional libraries some are stated to hold more than 12,000 books. Some of Merv's libraries resources were highly unique and precious not to be found anywhere else, as he stated. Patrons could easily check out a large number of items from these book collections. As Hamawi reported he was allowed to keep more than 200 books on a long period loan. Most of these valuable libraries were burnt and ruined by the Mughals.

* Rab'-e Rashidi

Rab'-e Rashidi ( fa, رَبع رشیدی) was the site of a complex, including a school and workshop for producing books in the north-eastern part of the city of Tabriz, Iran, constructed in the early 14th century during the reign of Ghazan, a rul ...

Library-Maragheh

Maragheh ( fa, مراغه, Marāgheh or ''Marāgha''; az, ماراغا ) is a city and capital of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Maragheh is on the bank of the river Sufi Chay. The population consists mostly of Iranian Azerb ...

-13th century: Rashid al-Din Hamadani

Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb ( fa, رشیدالدین طبیب; 1247–1318; also known as Rashīd al-Dīn Faḍlullāh Hamadānī, fa, links=no, رشیدالدین فضلالله همدانی) was a statesman, historian and physician in Ilk ...

, the Iranian author of Universal History and the Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...