History of French-era Tunisia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Tunisia under French rule started in 1881 with the establishment of the French protectorate and ended in 1956 with

As the 19th century commenced, the

As the 19th century commenced, the

France, whose possession of Algeria bordered Tunisia, and Britain, then possessing the tiny island of Malta lying off its coast, were also interested. Britain wanted to avoid a single power controlling both sides of the

France, whose possession of Algeria bordered Tunisia, and Britain, then possessing the tiny island of Malta lying off its coast, were also interested. Britain wanted to avoid a single power controlling both sides of the  In northwest Tunisia the Khroumir tribe episodically launched raids into the surrounding countryside. In Spring of 1881 they raided across the border into French

In northwest Tunisia the Khroumir tribe episodically launched raids into the surrounding countryside. In Spring of 1881 they raided across the border into French

The

The

Yet educational modernizing had preceded the French to a limited extent. The

Yet educational modernizing had preceded the French to a limited extent. The  The innovations in

The innovations in

The latter expansion began when the restored royalist regime captured

The latter expansion began when the restored royalist regime captured  In

In

Arab culture has strongly affected Tunisia since the 8th century conquest and subsequent Arab migrations. Tunisia became an Arabic-speaking, Muslim country closely connected with the Mashriq (the Arab east). Long before the recent rise of Europe, and for centuries sharing this distinction with distant China, Muslim Arab civilization led the world in the refinement and in the prosperity of its citizens. Yet since, Turkish armies arrived from Central Asia and Turks eventually moved into leadership position at various Muslim polities, beginning about the 10th century. Thereafter, the Arabs ostensibly rested content under their foreign, albeit Islamic, rule. Moreover, about the year 1500 European Christians, once their rather opaque and trailing neighbors along the Mediterranean shore, "at last caught up with and overtook Islam, though the latter was quite unaware of what was happening."

Nonetheless the Arabs still retained a well-acknowledged double esteem as (a) the creators of the ancient world's earliest civilizations (when most spoke another Semitic language, i.e.,

Arab culture has strongly affected Tunisia since the 8th century conquest and subsequent Arab migrations. Tunisia became an Arabic-speaking, Muslim country closely connected with the Mashriq (the Arab east). Long before the recent rise of Europe, and for centuries sharing this distinction with distant China, Muslim Arab civilization led the world in the refinement and in the prosperity of its citizens. Yet since, Turkish armies arrived from Central Asia and Turks eventually moved into leadership position at various Muslim polities, beginning about the 10th century. Thereafter, the Arabs ostensibly rested content under their foreign, albeit Islamic, rule. Moreover, about the year 1500 European Christians, once their rather opaque and trailing neighbors along the Mediterranean shore, "at last caught up with and overtook Islam, though the latter was quite unaware of what was happening."

Nonetheless the Arabs still retained a well-acknowledged double esteem as (a) the creators of the ancient world's earliest civilizations (when most spoke another Semitic language, i.e.,  Another reformer with lasting influence in Tunisia was the Egyptian Shaykh

Another reformer with lasting influence in Tunisia was the Egyptian Shaykh

The

The  The learned Arabic weekly magazine ''al-Hādira''

The learned Arabic weekly magazine ''al-Hādira''  Late in 1911 issues concerning a Muslim cemetery, the Jellaz, sparked large nationalist demonstrations in Tunis. The protests and riots left dozens of Tunisians and Europeans dead. The French declared

Late in 1911 issues concerning a Muslim cemetery, the Jellaz, sparked large nationalist demonstrations in Tunis. The protests and riots left dozens of Tunisians and Europeans dead. The French declared

Although always relatively small in numbers (peaking at about 250,000), French settlers or '' colons'' became a very influential social stratum in Tunisia. They combined commercial-industrial expertise and know-how, with government privilege. Although not all the French were equally prosperous, ranging from rich to poor, nonetheless group cohesion was strong. French capital found investments in such activities as

Although always relatively small in numbers (peaking at about 250,000), French settlers or '' colons'' became a very influential social stratum in Tunisia. They combined commercial-industrial expertise and know-how, with government privilege. Although not all the French were equally prosperous, ranging from rich to poor, nonetheless group cohesion was strong. French capital found investments in such activities as  Usually, in response to any proposed economic development, French settlers would marshal their influence in order to reap the major benefits. For many French, such benefits were the ''raison d'être'' for their living in Tunisia. If the local French administrator on occasion decided against them, they would hasten to appeal to their political contacts in

Usually, in response to any proposed economic development, French settlers would marshal their influence in order to reap the major benefits. For many French, such benefits were the ''raison d'être'' for their living in Tunisia. If the local French administrator on occasion decided against them, they would hasten to appeal to their political contacts in

Near

Near

The stature of the Soviet Union, with its ostensibly 'anti-colonialist' ideology, was enhanced by its position as a primary victor in the war. Its doctrines demanded a harsh judgment on the French in North Africa. In this vein continued writers who may not have been communists. During the French presence, the maghriban resistance was articulated in sharper and more combative terms as the independence movements intensified. Especially bitter in accusation was the works of the iconic, anti-colonial writer of Algeria, Frantz Fanon. The United States of America, the other major victor and power following the war, also articulated a stance against the continued existence of colonies, despite remaining in alliance with European colonial states. Yet within several years of the war's end, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt had become independent, as had India and Pakistan and Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

In 1945 the

The stature of the Soviet Union, with its ostensibly 'anti-colonialist' ideology, was enhanced by its position as a primary victor in the war. Its doctrines demanded a harsh judgment on the French in North Africa. In this vein continued writers who may not have been communists. During the French presence, the maghriban resistance was articulated in sharper and more combative terms as the independence movements intensified. Especially bitter in accusation was the works of the iconic, anti-colonial writer of Algeria, Frantz Fanon. The United States of America, the other major victor and power following the war, also articulated a stance against the continued existence of colonies, despite remaining in alliance with European colonial states. Yet within several years of the war's end, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt had become independent, as had India and Pakistan and Sri Lanka, Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

In 1945 the

Following World War II the

Following World War II the

online

Background Note: Tunisia

''The World Factbook'' on "Tunisia"

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of French-Era Tunisia

Tunisian independence

Tunisian independence was a process that occurred from 1952 to 1956 between France and a separatist movement, led by Habib Bourguiba. He became the first Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Tunisia after negotiations with France successfully had br ...

. The French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

presence in Tunisia came five decades after their occupation of neighboring Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. Both of these lands had been associated with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

for three centuries, yet each had long since attained political autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

. Before the French arrived, the Bey of Tunisia had begun a process of modern reforms, but financial difficulties mounted, resulting in debt. A commission of European creditors then took over the finances. After the French conquest of Tunisia the French government assumed Tunisia's international obligations. Major developments and improvements were undertaken by the French in several areas, including transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, an ...

and infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

, industry, the financial system

A financial system is a system that allows the exchange of funds between financial market participants such as lenders, investors, and borrowers. Financial systems operate at national and global levels. Financial institutions consist of complex, c ...

, public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

, administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal

** Administrative assistant, Administrative Assistant, traditionally known as a Secretary, or also known as an admini ...

, and education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

. Although these developments were welcome, nonetheless French businesses and citizens were clearly being favored over Tunisians. Their ancient national sense was early expressed in speech and in print; political organization followed. The independence movement was already active before World War I, and continued to gain strength against mixed French opposition. Its ultimate aim was achieved in 1956.

Beylical reform, debt

Husaynid

The Husaynids ( ar, بنو حسين, Banū Ḥusayn) are a branch of the Alids who are descendants of Husayn ibn Ali, a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Along with the Hasanids, they form the two main branches of the .

Genealogical tr ...

dynasty Bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

remained the hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

ruler the country. Since the early 18th century Tunisia had been effectively autonomous, although still 'officially' an Ottoman province. Commerce and trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

with Europe increased dramatically following the Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Western merchants especially Italians arrived to establish businesses in the major cities. Italian farmers, tradesmen, and laborers also immigrated to Tunisia. With the rapid surge in contacts with Europe, foreign influence grew.

During the rule of Ahmad Bey (r.1837-1855) extensive modern reforms were initiated. Later, in 1861 Tunisia promulgated the first constitution in the Arab world. Yet the Tunisian drive toward modernizing the state and the economy met resistance. Reformers became frustrated by comfort-seeking insiders, political disorganization, regional discontent, and rural poverty. An 1864 revolt in the ''Sahil'' region was brutally put down. Later, after ineffective measures had failed, the leading reformer Khair al-Din (Khaïreddine) became chief minister 1873–1877, but he too eventually met defeat by wily conservative politicians.

European banks advanced funds to the Beylical government for modernizing projects, such as civil improvements, the military, public works, and development projects, but also they included money for the personal use of the Bey. The loans were frequently negotiated at unfavorable rates and terms. Repayment of this foreign debt eventually grew increasingly difficult to manage. In 1869, Tunisia declared itself bankrupt. A ''Commission Financière Internationale'' (International Financial Commission) was thereafter formed, whose representatives were led by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and included Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and Britain. This commission then took control over the Tunisian economy.

French regime

Presented here are the commencement and the early history of the Protectorate, including institutional profiles, economic accomplishments, and reforms. "On the whole the urban and settled parts of the Tunisian population did not evince great hostility to the French protectorate in the pre-First World War period." The changing political configurations variously dominant in Metropolitan France are also summarized.Establishment

Initially, Italy was the European country most interested in incorporating Tunisia into its sphere of influence. Italy's strong motivation derived from the substantial number of expatriate citizens already resident there, with corresponding business investment, due to its close geography. Yet in the emerging national conscience of the newly unified (1861) Italian state, the establishment of a directly ruled colony did not then attract high-priority interest for the political agenda. France, whose possession of Algeria bordered Tunisia, and Britain, then possessing the tiny island of Malta lying off its coast, were also interested. Britain wanted to avoid a single power controlling both sides of the

France, whose possession of Algeria bordered Tunisia, and Britain, then possessing the tiny island of Malta lying off its coast, were also interested. Britain wanted to avoid a single power controlling both sides of the Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily (also known as Sicilian Strait, Sicilian Channel, Channel of Sicily, Sicilian Narrows and Pantelleria Channel; it, Canale di Sicilia or the Stretto di Sicilia; scn, Canali di Sicilia or Strittu di Sicilia, ar, مضيق ص ...

. During 1871–1878, France and Britain had been co-operating to foreclose Italian political influence. Yet more often these two countries were keen rivals. "For most of their tenure oth began in 1855 Richard Wood and Léon Roches, the consuls respectively of Britain and France, competed fiercely with each other to gain an economic or political edge in Tunisia."

The Congress of Berlin, held in 1878, convened to discuss the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, the "sick man" of Europe, following its decisive defeat by Russia, with a focus on its remaining Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

possessions. At the Congress, an informal understanding among the British, Germans, and French was reached, assenting to France incorporating Tunisia, although the negotiations around this understanding were kept secret from the Italians at the time. The French Foreign Minister, William Waddington, discussed the matter extensively with Britain's Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, and Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, while originally opposed, came to view Tunisia as an ideal distraction of the French away from continental Europe by the time of the Congress. Italy was promised Tarabulus in what became Libya. Britain supported French influence in Tunisia in exchange for its own protectorate over Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

(recently 'purchased' from the Ottomans), and French cooperation regarding a nationalist revolt in Egypt. In the meantime, however, an Italian company apparently bought the Tunis-Goletta-Marsa rail line; yet French strategy worked to circumvent this and other issues created by the sizeable colony of Tunisian Italians

Italian Tunisians (or Italians of Tunisia) are Tunisians of Italian descent. Migration and colonization, particularly during the 19th century, led to significant numbers of Italians settling in Tunisia.

Italian presence in Tunisia

The presence ...

. Direct attempts by the French to negotiate with the Bey their entry into Tunisia failed. France waited, searching to find reasons to justify the timing of a pre-emptive strike, now actively contemplated. Italians would call such strike the ''Schiaffo di Tunisi

The Schiaffo di Tunisi (literally Slap of Tunis in English), was an expression used by the Italian press and historiographers from the end of the 19th century to describe an episode of the political crisis elapsed at the time between the Kingdom ...

''.

In northwest Tunisia the Khroumir tribe episodically launched raids into the surrounding countryside. In Spring of 1881 they raided across the border into French

In northwest Tunisia the Khroumir tribe episodically launched raids into the surrounding countryside. In Spring of 1881 they raided across the border into French Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. France responded by invading Tunisia, sending in an army of about 36,000. Their advance to Tunis was rapidly executed. The Bey was soon compelled to come to terms with the French conquest of the country, in the first of a series of treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

. These documents provided that the Bey continue as head of state, but with the French given effective control over a great deal of Tunisian governance, in the form of the ''Protectorat français en Tunisie''.Kenneth J. Perkins, ''A History of Modern Tunisia'' (Cambridge University 2004), pp. 10–12, 36–38.

With her own substantial interests in Tunisia, Italy protested but would not risk a confrontation with France. Hence Tunisia officially became a French protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

on May 12, 1881, when the ruling Sadik Bey (1859–1882) signed at his palace the Treaty of Bardo

The Treaty of Bardo (french: Traité du Bardo, ar, معاهدة باردو) or Treaty of Qsar es-S'id, Treaty of Ksar Said established a French protectorate over Tunisia that lasted until World War II. It was signed on 12 May 1881 between repre ...

(Al Qasr as Sa'id). Later in 1883 his younger brother and successor 'Ali Bey signed the Conventions of La Marsa

The Conventions of La Marsa ( ar, اتفاقية المرسى) supplementing the Treaty of Bardo were signed by the Bey of Tunis Ali III ibn al-Husayn and the French Resident General Paul Cambon on 8 June 1883. They provided for France to repay T ...

. Resistance by autonomous local forces in the south, encouraged by the Ottomans in Tarabulus, continued for half a year longer, with instability remaining for several years.

Paul Cambon

Pierre Paul Cambon (20 January 1843 – 29 May 1924) was a French diplomat and brother to Jules Cambon.

Biography

Cambon was born and died in Paris. He was called to the Parisian bar, and became private secretary to Jules Ferry in the ''préfe ...

, the first Resident-Minister (after 1885 called the Resident-General) of the French Protectorate, arrived in early 1882. According to agreement he assumed the office of the Bey's foreign minister, while the general commanding French troops became the minister of war. Soon another Frenchman became director-general of finance. Sadiq Bey died within a few months. Cambon wanted to demonstrate the complete disestablishment of Ottoman claims to suzerainty in Tunisia. The Ottomans beforehand agreed to acquiesce. Accordingly, Cambon designed and orchestrated the accession ceremony of 'Ali Bey (1882–1902). Cambon personally accompanying him from his La Marsa residence to the Bardo Palace where Cambon invested him as the new Bey in the name of France.

Economic advance

The French progressively assumed more of the important administrative positions. By 1884 they directed or supervised the Tunisian administration of government bureaus dealing withfinance

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fina ...

, post, education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

, telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, public works and agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

. After deciding to guarantee the Tunisian state debt

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The ...

(chiefly to European investors), the Protectorate then abolished the international finance commission. French settlements in the country were being actively encouraged; the number of French colons grew from 10,000 in 1891, to 46,000 in 1911, and then to total 144,000 in 1945.

The

The transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, ...

system was developed by the construction of railroads and highways, as well as sea ports. Already by 1884 the Compagnie du Bône-Guelma had built a rail line running from Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

west 1,600 km to Algiers, passing through the fertile Medjerda

The Medjerda River ( ar, وادي مجردة), the classical Bagrada, is a river in North Africa flowing from northeast Algeria through Tunisia before emptying into the Gulf of Tunis and Lake of Tunis. With a length of , it is the longest river ...

river valley near Beja and over the high tell. Eventually rail lines were built all along the coast from the northwest at Tabarka

Tabarka ( ar, طبرقة ') is a coastal town located in north-western Tunisia, close to the border with Algeria. Tabarka's history is a mosaic of Berber, Punic, Hellenistic, Roman, Arabic, Genoese and Turkish culture. The town is dominated b ...

to Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

, to Tunis and Sousse

Sousse or Soussa ( ar, سوسة, ; Berber:''Susa'') is a city in Tunisia, capital of the Sousse Governorate. Located south of the capital Tunis, the city has 271,428 inhabitants (2014). Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf ...

, to Sfax and Gabès; inland routes went from the coastal ports to Gafsa, to Kasserine

Kasserine ( ar, القصرين, al-Qasrīn, Tunisian Arabic: ڨصرين ') is the capital city of the Kasserine Governorate, in west-central Tunisia. It is situated below Jebel ech Chambi ( جبل الشعانبي), Tunisia's highest mountain. It ...

, and to El Kef

El Kef ( ar, الكاف '), also known as ''Le Kef'', is a city in northwestern Tunisia. It serves as the capital of the Kef Governorate.

El Kef is situated to the west of Tunis and some east of the border between Algeria and Tunisia. It has a ...

. Highways were also constructed. Geologists from French mining companies scrutinized the land for hidden resources, and invested in various projects. Railroads and ports often became ancillary developments to mining operations. Among the deposits discovered and extracted for export, phosphates (a salt of phosphoric acid, used chiefly as fertilizer) became the most important, mined near the south-central city of Gafsa. One company was awarded the concession to develop the mines and build the railroad, another to construct the port facilities at Sfax. The Compagnie des Phosphates et Chemins de Fer de Gafsa became the largest employer and taxpayer in the Protectorate. Iron and other minerals including zinc, lead, and copper, were also first profitably mined during the French era.

Tunisian nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

s would complain that these improvements, e.g., the rail and mining operations, were intended to benefit primarily France; the French profited most, and the employment opportunities were open more to French colons than to Tunisians. French companies provided their own engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

, technicians, managers, and accountants, and most of the skilled work force. Another major grievance of nationalist critics regarded the 'flood' of cheap manufactured goods entering the Tunisian market. This competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

worked havoc with the large artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

class, until then in good health and vigor, who made comparable goods by hand according to tradition. Here, the French did no more than passively introduce into Tunisia the fruits of advanced production techniques, and then let neutral market forces

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering ...

wreck their destruction on the local merchants, who could not compete on price.

Under the Protectorate, the social infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

was also improved, e.g., by school construction (see below, ''Education reform''), and the erection of public buildings for meetings and performances. Civic improvements included the provision of new sources of clean water and the construction of public sanitation facilities in Tunis, and other large cities. Hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

s were built, the number of medical doctor

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

s increased, vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

s became common, hence fatalities due to epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

s and other ills decreased; the per annum death-rate dropped dramatically. As a result, the Tunisian population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...

steadily increased, the number of Muslims about doubling between 1881 and 1946.

Regarding agriculture, French settlers and companies acquired farm lands in such quantities as to cause resentment among Tunisians. ''Habis'' rural properties (land held in religious trust or ''wafq''), and also tribal lands held in common, were made available for monetary purchase due to fundamental changes in the land law legislated by the Protectorate. The social utility of farm lands, in extent and intensity, advanced, especially regarding production of olive groves and of vineyards.

In rural areas the French administration strengthened the local officials (''qa'ids'') and weakened the independent tribes. Nationwide an additional judicial system was established for Europeans but available generally, set-up without interfering with the existing Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

courts, available as always for the legal matters of Tunisians.

Education reform

The French presence, despite its negatives, did present Tunisians with opportunities to become better acquainted with recent European advances. Modernizing projects had already been an articulated goal of the reform movements initiated under the Beys prior to the French. Among the areas of study that were sought for their practical value were agriculture, mining, urban sanitation, business and commerce, banking and finance, state administration, manufacture and technology, and education. Prior to the Protectorate the schools open to the majority of Tunisians were religious, e.g., the many local ''kuttab'' whose curriculum centered on the memorization and study of the Qur'an. These schools were usually proximous to the mosque and run by theimam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

. Students might progress to further such instruction at advanced schools. Especially noteworthy in this regard, but at the highest level, was the leading theological facility at the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan, founded circa 670. During the 9th-11th centuries, in addition to religious subjects, medicine, botany, astronomy, and math were taught. Above all the Uqba Mosque then was the center of the Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

school of law. Muslim scholars, the ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

from throughout northern Africa, came here to study.

Yet educational modernizing had preceded the French to a limited extent. The

Yet educational modernizing had preceded the French to a limited extent. The Zitouna Mosque

Al-Zaytuna Mosque, also known as Ez-Zitouna Mosque, and El-Zituna Mosque ( ar, جامع الزيتونة, literally meaning ''the Mosque of Olive''), is a major mosque at the center of the Medina of Tunis in Tunis, Tunisia. The mosque is the oldes ...

school in Tunis, which accepted the best graduates of the ''kuttab'' primary schools, had begun to add more secular topics to its predominantly Muslim curriculum. Also, the reforming prime minister Khair al-Din had at Tunis in 1875 established Sadiki College

Sadiki College, also known as ''Collège Sadiki'' ( aeb, المدرسة الصادقية, "El-Sadqiya High School"), is a '' lycée'' (high school) in Tunis, Tunisia. It was established in 1875. Associations formed by its alumni played a major rol ...

, a secondary school (lycee

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

), which from the first taught a curriculum oriented toward the modern world, instruction being in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

and also in several European languages. Jews also had maintained their own schools, as did the more recently arrived Italians.

During the French Protectorate, the goals of Tunisian educators in general developed, so as to include more the introduction of modern fields of study, namely, those leading toward the utilitarian knowledge practiced in Europe. Accordingly, in France such skills were well known, and a French technical vocabulary entered working use in Tunisia for various Protectorate projects, commercial and industrial. The French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

was the favored medium in new schools set up by the French Church, initially established primarily for children of French settlers, such as Collège Saint-Charles de Tunis in 1875. Yet many urban Tunisians also sought for their children learning opportunities oriented to the acquisition of modern skills useful in the workplace. The Tunisian elites struggled against Protectorate resistance to such access. Over time, and not without contested issues, a new educational regime was created, including instruction in French open to Tunisians. This took place in the political context of the Protectorate, of course, affecting the existing Muslim institutions of learning, secular Tunisian advancement, and the instruction of young French colons.

The innovations in

The innovations in education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

raised tender social issues in Tunisia. Yet many of such controversies were not new to the French, whose own educational institutions had met fundamental change during the 19th century. As France had come to develop and employ new technologies and the learning of the industrial age, French schooling adapted, and also became open to scrutiny. The balance between the teaching of traditional morality versus modern utilitarian skills, as well as exactly how and which morals to teach, became greatly contested in light of the wider French debate between religious versus secular values; it involved left-republican anticlerical politics. Similar issues arose later in Tunisia, including the views of the national movement.

In Tunisia the French in 1883 set up a ''Direction de l'Enseignement Public'' (Directorate of Public Education) to promote schools for teaching children of French officials and colons, and to further the spreading use of the French language. Its goals widened to include education in general. This Directorate eventually administered, or directed, all the different educational institutions and systems in Tunisia, which it sought to modernize, coordinate, grow and expand. Soon established in Tunis were the new mixed Collège Alaoui, and for women the new École Rue du Pacha and École Louise René Millet.

Several separate educational systems eventually resulted under the Protectorate. Serving French ''colons'' and Tunisians was a primary and secondary system closely coordinated with Metropolitan France, using the French language. From here students might attend a university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

in France. The government also directed a modern secular system of schools using mixed French and Arabic. The ''kuttab'' primary schools remained, keeping their religious instruction, yet enhanced by arithmetic, history, French, and hygiene; taught primarily in Arabic, the ''kuttab'' received government support. Thus Zitouna Mosque students might come from either the mixed secular or the ''kuttab'' religious schools. Zitouna education continued to expand, running four-year secondary schools at Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, Sfax, and Gabes, and also a program at the university level, while remaining a traditional Islamic institution. Sadiki College, however, became the premier ''lycée'' in the country, which offered to an emerging Tunisian elite a secular, well-developed, French-language program. These reforms set the stage for further advances made in Tunisian education since independence.

French context

The French brought all the contradictions and internal conflicts of their culture to North Africa. Briefly a review follows of the broad context in which France approached, traded with and financed, invaded, and then administered Tunisia. It will be seen that modern French politics not only guided the direction of the French colonial venture, but also informed indirectly and in combination with traditions the politics of their clients, the Tunisian people and their leadership. France was not unfamiliar with rule over foreign lands, i.e., two distinct phases of expansion outside Europe, and one within: the 16th–18th century ventures in North America and in India, which lands were lost by themonarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

in 1763 prior to the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

; the Napoleonic

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

conquests over most of western and central Europe, lost in 1815; and then the 19th and 20th century colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

in Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

The latter expansion began when the restored royalist regime captured

The latter expansion began when the restored royalist regime captured Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

in 1830. That same year, however, the '' Légitimist'' Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

king was overthrown by the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

in favor of a new '' Orléanist'' king. Yet this new version of constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, perhaps more liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

, did not resolve the persistent social conflict between (a) the traditional royalists (now divided), (b) the arrived and courted middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

, and (c) the neglected republicans (called "neo-Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

s" after the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

). The latter supported a democratic popular sovereignty and, from a distance, the emerging urban working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

.

In both the aristocrat and the peasant, religious practice generally remained strong. In the emergent middle class, religion competed with secular values backed by "scientism

Scientism is the opinion that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

While the term was defined originally to mean "methods and attitudes typical of or attributed to natural scientis ...

". Many urban workers began neglecting religious practice In the late 19th century, republican anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

peaked. The divergent viewpoints evident here, under various guises, continued to divide French society, whether subtly, or dramatically, or catastrophically, well into the 20th century. A dissimilar though somewhat analogous social array may be discerned at work in the political dynamics of modern and independent Tunisia.

In

In 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

the French people overthrew the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

of King Louis-Philippe; however, radical urban workers were quelled. Although for a time democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

replaced royalty, the voters remained conservative, still fearful of instability from the republican left, and under the sway of traditional social hierarchies. Over the republican candidate, Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

won the December election of 1848 by a huge landslide. An 1851 coup then confirmed the result: the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Empire, Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the French Second Republic, Second and the French Third Republic ...

. Because of his 1871 defeat by Germany, France lost its two-centuries-old position as the leading power in continental Europe. Yet the new French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

(1871–1940) arose, and quickly prospered. Many progressives from Asia, Africa, and the Americas still "regarded Paris as the spiritual capital of the world".

France returned to popular sovereignty. After first turning to constitutional monarchists who nonetheless instituted the republic, the voters later elected republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

, even socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

on occasion. The right was stymied by its own illusions, e.g., in the Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

. Even though socially and politically divided, in the next conflict, the disastrous World War

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

(1914–1918), France emerged triumphant.

In 1881 Jules Ferry (1832–1893), the republican premier and moderate anti-cleric, negotiated a political consensus to enable him to order the French army's conquest of Tunisia. During the subsequent Protectorate a change in French domestic political fortunes could directly impact Tunisian issues. For example, the 1936 election of Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister.

As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of French Socialist le ...

and the ''Front Populaire

The Popular Front (french: Front populaire) was an alliance of French left-wing movements, including the communist French Communist Party (PCF), the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) and the progressive Radical-Soci ...

'' reportedly improved official French comprehension of Tunisian aspirations.

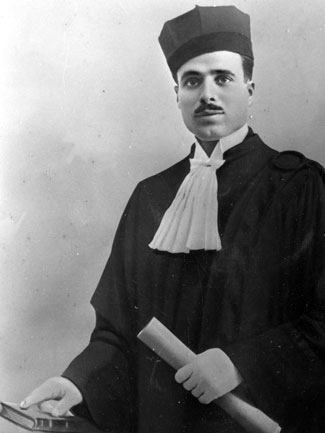

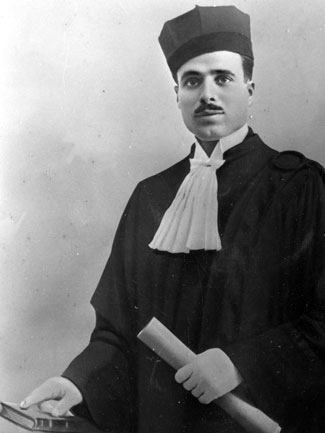

During the 1920s Habib Bourguiba

Habib Bourguiba (; ar, الحبيب بورقيبة, al-Ḥabīb Būrqībah; 3 August 19036 April 2000) was a Tunisian lawyer, nationalist leader and statesman who led the country from 1956 to 1957 as the prime minister of the Kingdom of T ...

while studying for his law degree at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

astutely observed first hand how French politicians formulated and strategized their domestic agendas. Politically, Bourguiba's mind "had been formed in the Paris of the Third Republic." As independence leader and later the first President of Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba (1903–2000) became the constitutional architect of the Republic.

Tunisian politics

Relating chiefly to the ''status quo ante'' and early decades of the French Protectorate, the political factors discussed here persisted throughout the course of French rule in Tunisia. Their relative strengths, one to the other, however, changed markedly over time. In appraising the marked significance of the French era on Tunisia, one explanatory reason might be the large number of Europeans who became permanent residents in the country. Compared with the Ottomans, who settled perhaps several tens of thousands from their empire in Tunisia, the French and their Italian 'allies' settled hundreds of thousands.Islamic context

Most Tunisians are accustomed to references made about the Muslim world, for spiritual inspiration, literary metaphor, historical analogy. Within Islam the three primary cultural spheres, each stemming from a world ethno-linguistic civilization, are:Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

, Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

. Each influenced Islam as a whole, as its sophisticated cultural contours bear witness. Each likewise benefited Tunisia.

Preceding the French protectorate in Tunisia, the Ottoman Turks exercised varying degrees of suzerainty, and the ruling strata of Tunisia once spoke Turkish. Under its Arabizing rulers, the quasi-independent Beys

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

, an attempt at modern reform was made, which used as a model similar reforms in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Influence of the Iranian-sphere on Tunisia through the government has been only occasional, e.g., by the 8th-10th century Rustamid

The Rustamid dynasty () (or ''Rustumids'', ''Rostemids'') was a ruling house of Ibadi, Ibāḍī imam, imāms of Persian people, Persian descent centered in Algeria. The dynasty governed as a Muslim theocracy for a century and a half from its cap ...

state, and by al-Afghani.

Arab culture has strongly affected Tunisia since the 8th century conquest and subsequent Arab migrations. Tunisia became an Arabic-speaking, Muslim country closely connected with the Mashriq (the Arab east). Long before the recent rise of Europe, and for centuries sharing this distinction with distant China, Muslim Arab civilization led the world in the refinement and in the prosperity of its citizens. Yet since, Turkish armies arrived from Central Asia and Turks eventually moved into leadership position at various Muslim polities, beginning about the 10th century. Thereafter, the Arabs ostensibly rested content under their foreign, albeit Islamic, rule. Moreover, about the year 1500 European Christians, once their rather opaque and trailing neighbors along the Mediterranean shore, "at last caught up with and overtook Islam, though the latter was quite unaware of what was happening."

Nonetheless the Arabs still retained a well-acknowledged double esteem as (a) the creators of the ancient world's earliest civilizations (when most spoke another Semitic language, i.e.,

Arab culture has strongly affected Tunisia since the 8th century conquest and subsequent Arab migrations. Tunisia became an Arabic-speaking, Muslim country closely connected with the Mashriq (the Arab east). Long before the recent rise of Europe, and for centuries sharing this distinction with distant China, Muslim Arab civilization led the world in the refinement and in the prosperity of its citizens. Yet since, Turkish armies arrived from Central Asia and Turks eventually moved into leadership position at various Muslim polities, beginning about the 10th century. Thereafter, the Arabs ostensibly rested content under their foreign, albeit Islamic, rule. Moreover, about the year 1500 European Christians, once their rather opaque and trailing neighbors along the Mediterranean shore, "at last caught up with and overtook Islam, though the latter was quite unaware of what was happening."

Nonetheless the Arabs still retained a well-acknowledged double esteem as (a) the creators of the ancient world's earliest civilizations (when most spoke another Semitic language, i.e., Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

or Canaanite or Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, or spoke Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

), and later as (b) co-creators of the elegant and enduring Islamic civilization, with the desert Arabs (the original people of Muhammad), to whom they attached themselves as 'adopted' Semite cousins. Despite having earned and enjoyed such high esteem, the Arabs in more recent times found themselves thirsty for rejuvenation and renewal. During the 19th century a great renaissance began to stir among Arabs and among the Muslim peoples in general, giving rise to various reformers who conveyed their political and ideological messages.

Inspiring and enigmatic, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) traveled widely to rally the Muslim world to unity and internal reform. Later while in Paris in 1884 al-Afghani published with Muhammad 'Abduh (see below) a journal ''al-'Urwa al-wuthqa'' The Strongest Link"to propagate his message. He himself sought a leading position in government to initiate reinvigorating reforms. He managed for a time to associate with an Ottoman Sultan, and later with a Shah of Iran, but to no effect. Although advocating a pan-Islamic solution, al-Afghani also taught the adoption of a universal reason under Islamic principles whereby Muslim societies might be reformed and then master the European sciences; industry and commerce would transform Muslim material culture. Such modernizing did not convince the more traditionist among the ''ulema'', but did energize a popular following across Islam which became committed to reform agendas. Such rational principles were often welcome by Tunisian nationalists.

Another reformer with lasting influence in Tunisia was the Egyptian Shaykh

Another reformer with lasting influence in Tunisia was the Egyptian Shaykh Muhammad 'Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

(1849–1905), a follower of al-Afghani. A gifted teacher, he eventually became the Mufti of Egypt. 'Abduh cultivated reason and held the controversial view that in Muslim law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

the doors of ''ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a le ...

'' were open, i.e., permitting the learned to make an ''original'' interpretation of sacred texts. 'Abduh visited Tunisia twice. Together al-Afghani and 'Abduh have been called "the two founders of Islamic modernism".

In Tunisia a reformer also arose. Khair al-Din al-Tunsi

Hayreddin Pasha ( aeb, خير الدين باشا التونسي Khayr ed-Din Pasha et-Tunsi; ota, تونسلى حيرالدين پاشا; tr, Tunuslu Hayreddin Paşa; 1820 – 30 January 1890) was an Ottoman- Tunisian statesman and reforme ...

(1810–1889) urkish name: Hayreddin Pashawas an early reformer of Circassian origins. When a child he learned Turkish and eventually became an Ottoman Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

. As a young man he was brought to Tunisia to enter the declining Turkish-speaking elite. Here he spent several decades in the service of several Bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

s (1840s-1877), when he chose to adopt the Maghrib as his own and learned Arabic. Khair al-Din has been discussed previously. He preceded al-Afghani, and appeared to be more traditionally religious. He came of age in the era of the Ottoman Tanzimat

The Tanzimat (; ota, تنظيمات, translit=Tanzimāt, lit=Reorganization, ''see'' nizām) was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. ...

, a series of modern reforms begun in 1839. Khair al-Din advocated a modern rationalism in the reform of society and government, yet one respectful of Muslim institutions. Once in power in Tunisia to implement his reforms (1873–1877), Khair al-Din encountered stiff opposition and was replaced mid-steam.

Later the Tunisian Shaykh Mahammad al-Sanusi led a group which "adhered to the ideology expounded by Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Shaykh Muhammad 'Abduh." An alim

Alim (''ʿAlīm'' , also anglicized as ''Aleem'') is one of the Names of God in Islam, meaning "''All-knowing one''". It is also used as a personal name, as a short form of Abdul Alim, "''Servant of the All-Knowing''":

Given name

* Alim ad-Din A ...

in the service of the Bey before the Protectorate commenced in 1881, thereafter al-Sunusi traveled east on pilgrimage where he claimed to have entered "an anti-Western secret society" founded by al-Afghani. Soon 'Abduh visited Tunisia, where he was greeted by "reformist ulama" supporters of Khayr al-Din. During the next year 1885 occurred a formal protest to the Bey against tax and tariff measures of the new French regime. Involved were 60 notables, featuring al-Sanusi and public demonstrations; it likely constituted an "alliance between mosque and bazaar

A bazaar () or souk (; also transliterated as souq) is a marketplace consisting of multiple small Market stall, stalls or shops, especially in the Middle East, the Balkans, North Africa and India. However, temporary open markets elsewhere, suc ...

." Yet the protest was ineffective; the dispute was settled. In character this protest group differed from the nationalist movement to come, but adumbrated it. Banished by the French, al-Sanusi responded with "a concilliatory letter" and was reinstated. During its first two decades the subject people remained "content to pursue Tunisian development within the Protectorate framework."

Alongside the pan-Islamic were conflated ethnic views, i.e., conflicting pan-Arab and pan-Turkic. Many Arabic-speaking countries under Ottoman rule had grown weary; a popular desire for self-rule under an Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

arose. In this regard Tunisia differed: an Arabic-speaking country but already long liberated from the Ottomans, governed by an autonomous Bey where the imperial hand was merely ceremonial. Tunisia experienced no fight against the Turkish empire, whereas during World War I many mashriq Arabs fought against Turkish armies for their independence.

Yet in 1881 Tunisia fell under European rule, as did Egypt in 1882, Morocco and Libya in 1912, and Syria and Iraq in 1919. Early in the 20th century the Tunisian resistance movement against France emerged. It later would enjoy two distinct sources of Islamic political culture. For Muslim fraternity, e.g., for a forum in which to compare ideas and programs, Tunisians could choose between: the Ottomans (latter Turkey), and the Arab world to the east (the Mashriq and Egypt).

Nationalist origins

The

The Bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

of Tunis was the traditional, authoritarian ruler. Under the Protectorate the Bey's rule continued ''de jure'', yet ''de facto'' control of the country passed to the French ''Resident General

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of indir ...

'' and his ministers, appointed in Paris. The Bey continued in his lesser role as a figurehead monarch. Yet his position had been tarnished by the court's "prodigality and corruption" and the cynical aristocracy. The harsh put down of the 1864 revolt in the ''Sahil'' was still remembered a century later. During the first decade, notables and conservative Tunisians had appealed to Ali Bey to effectively mediate with the French. His ability to maneuver was closely confined. "In Tunisia, obedience to the Bey meant submission to the French." Yet the Bey stirred some Tunisian culture into the foreign recipe.

Indeed, many Tunisians at first welcomed the progressive changes brought about by the French, but the general consensus that evolved was that Tunisians preferred to manage their own affairs. Before the French conquest, during the 1860s and 1870s Khair al-Din had introduced modernizing reforms in Tunisia. His innovative ideas, although acknowledging the ascendancy of Europe, remained conversant with Islamic tradition and favored reform on Islamic terms. He wrote an influential book.

The learned Arabic weekly magazine ''al-Hādira''

The learned Arabic weekly magazine ''al-Hādira'' he Capital

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

was founded in 1888 by companions and followers of the reforming Beylical minister Khair al-Din. The weekly discussed politics, history, economics, Europe and the world, and was published until 1910. This moderate magazine of the Tunisian establishment articulated views that were often pitched to the ''baldiyya'' (merchants) and the ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (clerics and jurists). It voiced perspectives found in Khair al-Din's 1867 book on Islam confronting the modern. The "organized body of reformers and patriots" who started the weekly were influenced by the Egyptian Muhammad 'Abduh

; "The Theology of Unity")

, alma_mater = Al-Azhar University

, office1 = Grand Mufti of Egypt

, term1 = 1899 – 1905

, Sufi_order = Shadhiliyya

, disciple_of =

, awards =

, in ...

and his 1884-1885 visit to Tunisia; Shaykh 'Abduh had advocated moderation. Many of the reasonable editorials in ''al-Hadirah'' were written by as-Sanusi. According to Tunisian author Ibn Ashūr, writing decades later, al-Sanusi's distasteful experience with the early Tunisian opposition to French rule had caused him to re-evaluate the Protectorate, positively.

A radical weekly publication ''az-Zuhrah'' was openly critical of French policy, and ran from 1890 until suppressed in 1897. Another periodical uneasy with the status quo and terminated by French authorities was ''Sabil al-Rashad'', 1895–1897. It was published by 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Tha'alibi, who was educated at Zaytuna. The young Tha'alibi, destined to play a leading intellectual role, was another directly inspired by 'Abduh of Cairo, and by earlier, local reformers, e.g., Mahmud Qabadu Mahmud Qabadu (1812–1872) of Tunisia, also Muhammad Qabadu, was a scholar of Quranic studies, a progressive member of the ulama, a long-time professor at the Zaytuna mosque academy, and a poet. Shaykh Mahmūd Qabādū served as a qadi to the chie ...

.

In 1896 Bashir Sfar and other advocates of renewal from ''al-Hādira'' founded ''al-Jam'iyah Khalduniya'' he Khaldun Society its charter was approved by a French decree. The society provided a forum for sophisticated discussions; it was named after the famous medieval historian of Tunis Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

. According to professor Laroui, it "emphasized the need for gradual reform" of education and the family. ''Khalduniya'' also facilitated the role played by ''ulama'' progressives at Zitouna Mosque

Al-Zaytuna Mosque, also known as Ez-Zitouna Mosque, and El-Zituna Mosque ( ar, جامع الزيتونة, literally meaning ''the Mosque of Olive''), is a major mosque at the center of the Medina of Tunis in Tunis, Tunisia. The mosque is the oldes ...

. ''Khalduniya'', wrote Laroui "became increasingly French both in mentality and in language." The ''Khalduniya'' society "opened a window on the West for Arabic-speaking Tunisians," comments professor Perkins. It offered to the public free classes in European sciences. Many decades later, regarding the new political party Neo-Destour

The New Constitutional Liberal Party ( ar, الحزب الحر الدستوري الجديد, '; French: ''Nouveau Parti libéral constitutionnel''), most commonly known as Neo Destour, was a Tunisian political party founded in 1934 by a group o ...

, ''Khalduniya'' (and Sadiki College) "channeled many young men, and a few women, into the party." ''Khalduniya'' also helped create the demand in Tunisia for foreign Arabic newspapers and magazines.

Other Tunisian periodicals continued to enter the marketplace of ideas. Ali Bach Hamba

Ali Bach Hamba (1876 - 29 October 1918) was a Tunisian lawyer, journalist and politician. He co-founded the Young Tunisians with Béchir Sfar in 1907.

Biography

Bach Hamba was born in 1876 in Tunis into a family of Turkish origin, his brother, ...

founded the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

journal ''le Tunisien'' in 1907, in part to inform the European public of Tunisian views. The opinions it expressed seemed not only to further mutual understanding, but to increase the unease and unrest. In 1909 Tha'alibi founded its Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

version ''at Tūnisī'', which among other issues challenged the pro-Ottoman Hanba from a more 'Tunisian' view point. Tha'alibi (1876-1944) is described in 1902, when he returned from Egypt, as "with strange attire, tendencies, thought and pen." His reform ideas struck "conservative leaders" as "an attack on Islam." In 1903 ath-Tha'alibi was "brought to trial as a renegade" and "sentenced to two months imprisonment."

As French rule continued, it appeared increasingly determined to favor the French and Europeans over native Tunisians. Accordingly, the general tone of the Tunisian response grew bitter and hardened into a challenging resolve. Here professor Kenneth Perkins marks the "transition from advocacy of social change to engagement in political activism." In 1911 civil disturbances were ignited by the Zaytuni university students. One result was that Bach Hamba and Tha'alibi reached an accord. A political party was begun, ''al-Ittihad al-Islami'', which thus expressed pan-Islamic leanings.

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

; they blamed political agitators. In 1912 further demonstrations led to the popular Tunis Tram Boycott. In response the French authorities closed the nationalist newspapers and sent into exile Tunisian leaders, e.g., Tha'alibi and Bach Hamba. Tha'alibi later would return to Tunisia.

According to professor Nicola Ziadeh, "the period between 1906 and 1910 saw a definite crystallization of the national movement in Tunisia. This crystallization centered around Islam." By the eve of the First World War (1914–1918), Tunisian 'nationalists' had developed and it adherents encountered an opportunity to publicly define themselves, in terms not only domestic but in light of widespread trends and foreign events. Pan-Islam had been promoted by the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid ʻAbd al-Ḥamīd ( ALA-LC romanization of ar, عبد الحميد) is a Muslim male given name, and in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' ʻabd'' and ''al-Ḥamīd'', one of the names of God in the Qur'an, which gave rise ...

, and such ideas also developed in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...