The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the

theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast

Pacific Ocean theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, the

South West Pacific theater

The South West Pacific theatre, during World War II, was a major theatre of the war between the Allies and the Axis. It included the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies (except for Sumatra), Borneo, Australia and its mandate Territory o ...

, the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

, and the

Soviet–Japanese War

The Soviet–Japanese War (russian: Советско-японская война; ja, ソ連対日参戦, soren tai nichi sansen, Soviet Union entry into war against Japan), known in Mongolia as the Liberation War of 1945 (), was a military ...

.

The Second Sino-Japanese War between the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

and the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

had been in progress since 7 July 1937, with hostilities dating back as far as 19 September 1931 with the

Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

. However, it is more widely accepted

that the Pacific War itself began on 7 December (8 December Japanese time) 1941, when the Japanese simultaneously

invaded Thailand, attacked the British colonies of

Malaya,

Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, and

Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

as well as the United States military and naval bases in

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

,

Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

,

Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, and

the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

The Pacific War saw the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

pitted against Japan, the latter aided by

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and to a lesser extent by the

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

allies,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

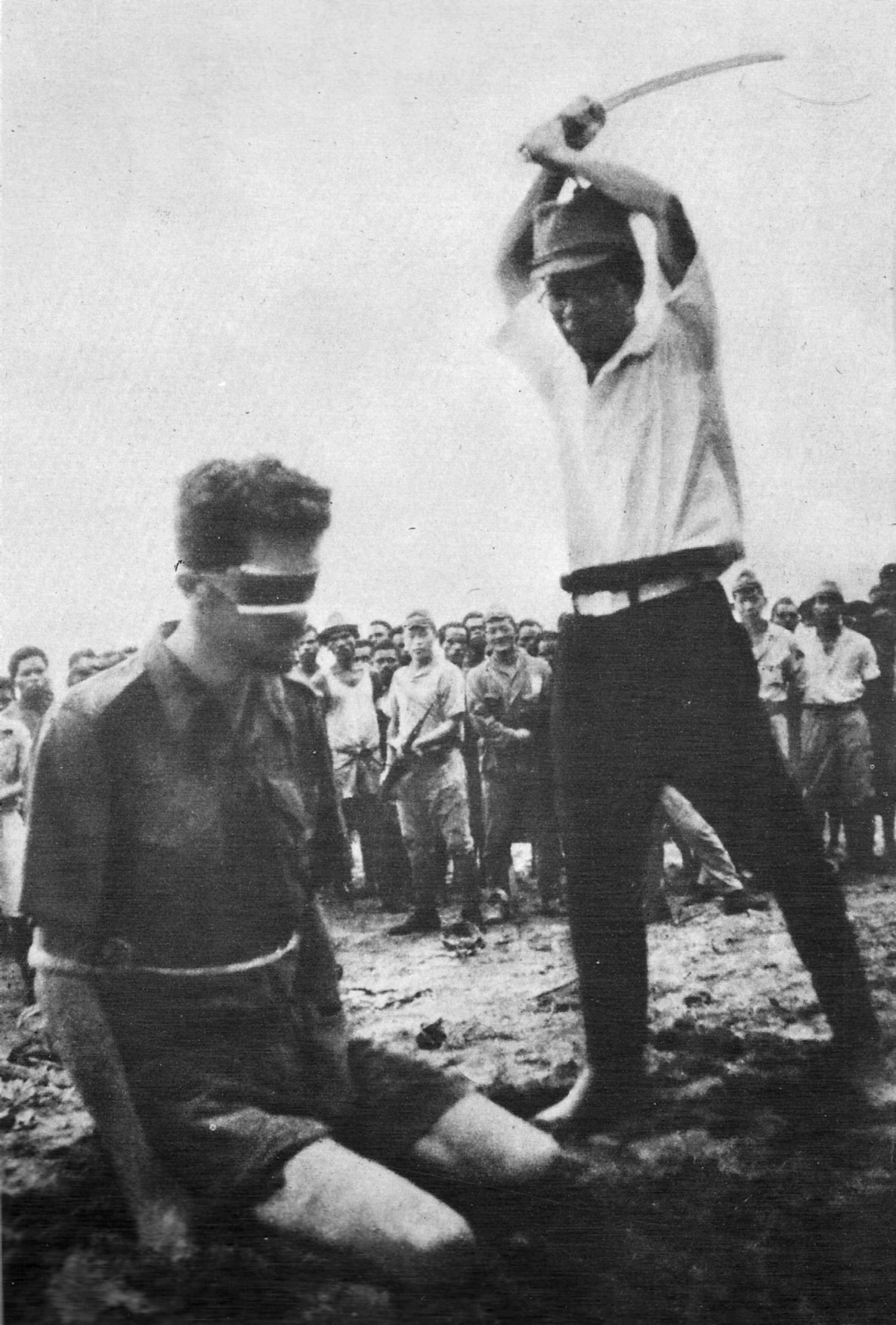

. Fighting consisted of some of the

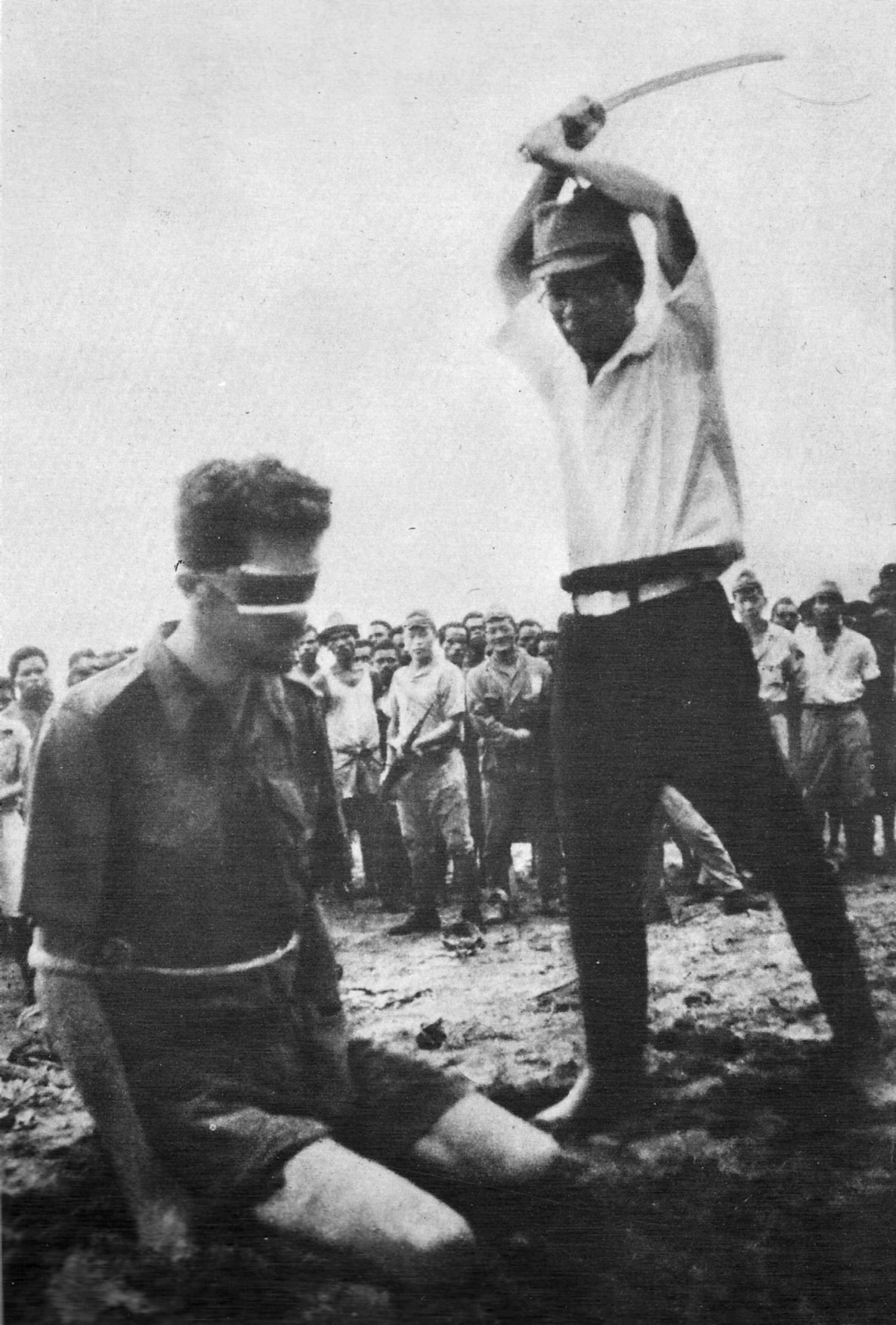

largest naval battles in history, and incredibly fierce battles and

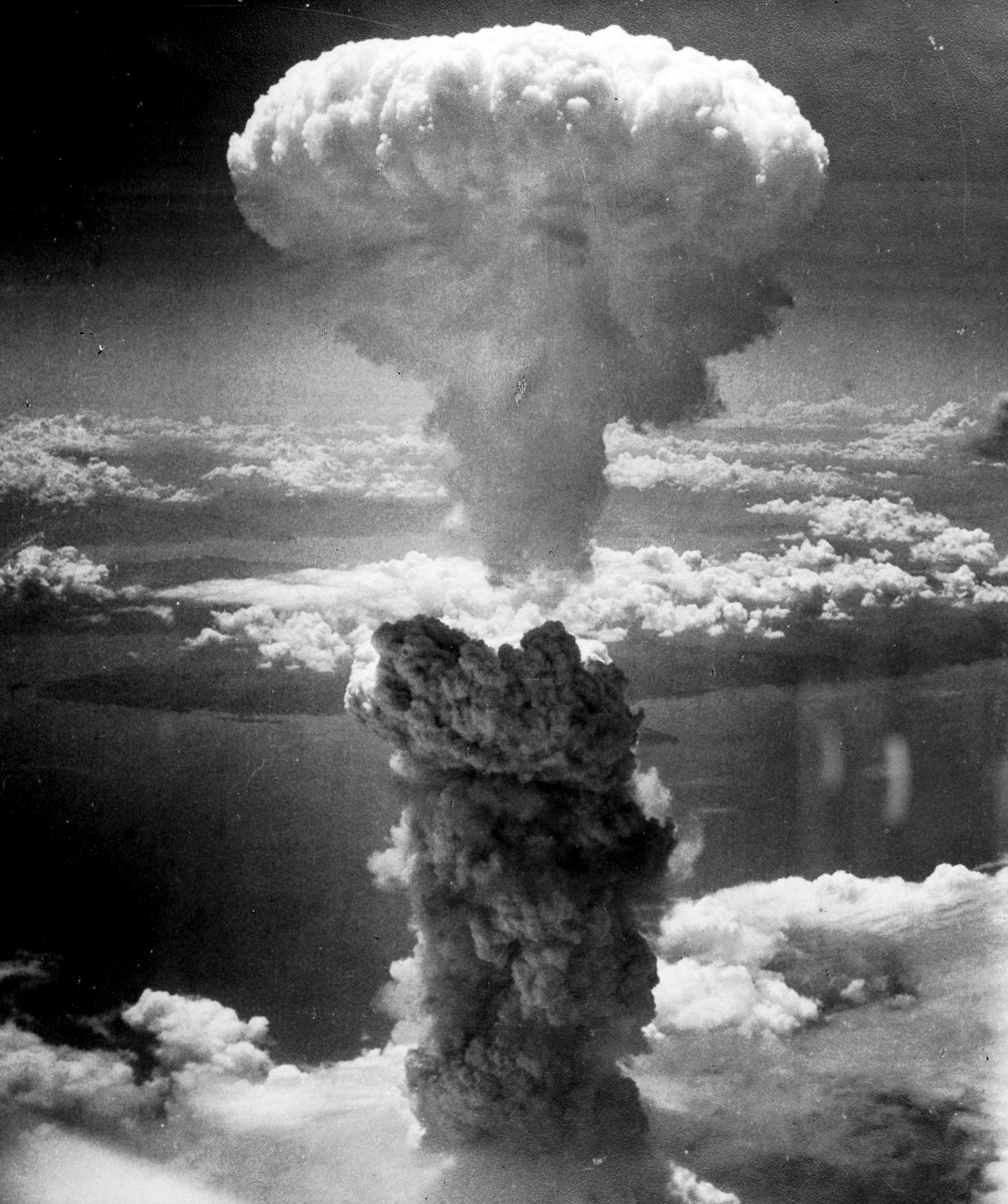

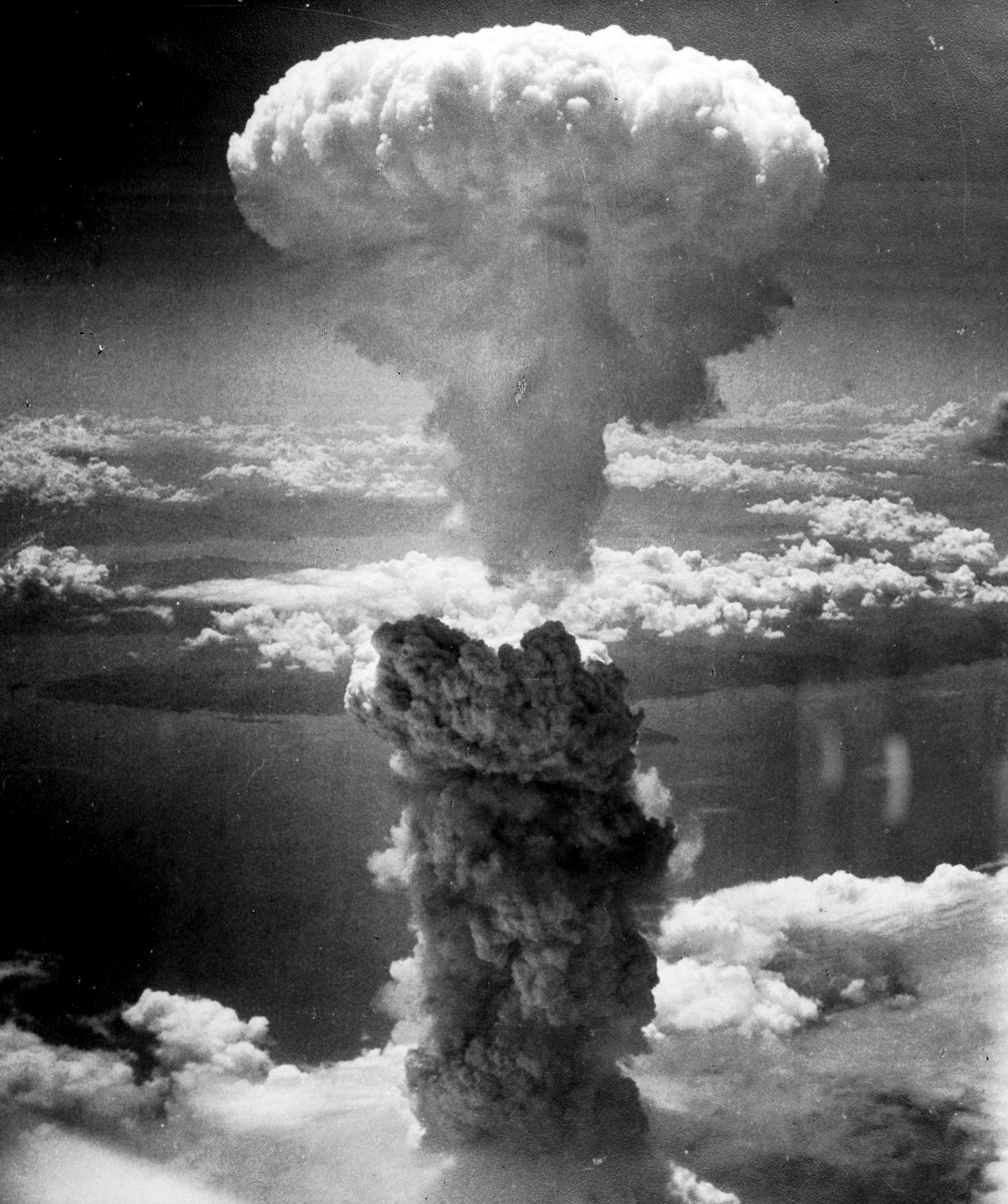

war crimes across Asia and the Pacific Islands, resulting in immense loss of human life. The war culminated in massive Allied

air raids over Japan, and the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, accompanied by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's

declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

and

invasion of Manchuria and other territories on 9 August 1945, causing the Japanese to

announce an intent to surrender on 15 August 1945. The formal

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

ceremony took place aboard the battleship in

Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populou ...

on 2 September 1945. After the war, Japan lost all rights and titles to its former

possessions in Asia and the Pacific, and its sovereignty was limited to the four main home islands and other minor islands as determined by the Allies. Japan's

Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shint ...

Emperor relinquished much of his authority and his divine status through the

Shinto Directive

The Shinto Directive was an order issued in 1945 to the Japanese government by Occupation authorities to abolish state support for the Shinto religion. This unofficial "State Shinto" was thought by Allies to have been a major contributor to ...

in order to pave the way for extensive cultural and political reforms.

Overview

Names for the war

In Allied countries during the war, the "Pacific War" was not usually distinguished from World War II in general, or was known simply as the ''War against Japan''. In the United States, the term ''

Pacific Theater'' was widely used, although this was a misnomer in relation to the

Allied campaign in Burma, the war in China and other activities within the

South-East Asian Theater. However, the US Armed Forces considered the

China-Burma-India Theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was offi ...

to be distinct from the Asiatic-Pacific Theater during the conflict.

Japan used the name , as chosen by a cabinet decision on 10 December 1941, to refer to both the war with the Western Allies and the ongoing war in China. This name was released to the public on 12 December, with an explanation that it involved Asian nations achieving their independence from the Western powers through armed forces of the

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

. Japanese officials integrated what they called the into the Greater East Asia War.

During the

Allied military occupation of Japan (1945–52), these Japanese terms were prohibited in official documents, although their informal usage continued, and the war became officially known as the . In Japan, the is also used, referring to the period from the

Mukden Incident

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

On September 18, 1931, ...

of 1931 through 1945.

Participants

Allies

The major

Allied participants were

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, the United States and the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. China had already been engaged in

bloody war against Japan since 1937 including both the

KMT government National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

and

CCP units, such as the guerrilla

Eighth Route Army

The Eighth Route Army (), officially known as the 18th Group Army of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, was a group army under the command of the Chinese Communist Party, nominally within the structure of the Chines ...

,

New Fourth Army

The New Fourth Army () was a unit of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China established in 1937. In contrast to most of the National Revolutionary Army, it was controlled by the Chinese Communist Party and not by the ruling Ku ...

, as well as smaller groups. The United States and its territories, including the

Philippine Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of the Philippines ( es, Commonwealth de Filipinas or ; tl, Komonwelt ng Pilipinas) was the administrative body that governed the Philippines from 1935 to 1946, aside from a period of exile in the Second World War from 1942 ...

, entered the war after

being attacked by Japan. The British Empire was also a major belligerent consisting of British troops along with large numbers of colonial troops from the armed forces of

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

as well as from

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

,

Malaya,

Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

,

Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

; in addition to troops from

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

,

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

and

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

. The

Dutch government-in-exile

The Dutch government-in-exile ( nl, Nederlandse regering in ballingschap), also known as the London Cabinet ( nl, Londens kabinet), was the government in exile of the Netherlands, supervised by Queen Wilhelmina, that fled to London after the G ...

(as the possessor of the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

) were also involved. All of these were members of the

Pacific War Council

The Pacific War Council was an inter-governmental body established in 1942 and intended to control the Allied war effort in the Pacific and Asian campaigns of World War II.

Following the establishment of the short-lived American-British-Dutch ...

. From 1944 the French commando group

Corps Léger d'Intervention

The Corps Léger d'Intervention (CLI) ( French for "light intervention corps") was a Pacific War interarm corps of the Far East French Expeditionary Forces commanded by Général de corps d'armée Roger Blaizot that used guerrilla warfare aga ...

also took part in resistance operations in Indochina. French Indochinese forces faced Japanese forces in

a coup in 1945. The commando corps continued to operate after the coup until liberation. Some active pro-allied guerrillas in Asia included the

Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a communist guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945. Composed mainly of ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest anti-Japanese re ...

, the

Korean Liberation Army

The Korean Liberation Army, also known as the Korean Restoration Army established on September 17, 1940, in Chungking, China, was the armed force of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. Its commandant was General Ji Cheong-cheon, ...

, the

Free Thai Movement

The Free Thai Movement ( th, เสรีไทย; ) was a Thai underground resistance movement against Imperial Japan during World War II. Seri Thai were an important source of military intelligence for the Allies in the region.

Background

I ...

, the

Việt Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fron ...

, and the

Hukbalahap

The Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon (), better known by the acronym Hukbalahap, was a communist guerrilla movement formed by the farmers of Central Luzon. They were originally formed to fight the Japanese, but extended their fight into a rebellio ...

.

The Soviet Union fought two short, undeclared

border conflicts with Japan

in 1938 and again

in 1939, then remained neutral through the

Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

of April 1941, until August 1945 when it (and

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

) joined the rest of the Allies and

invaded the territory of Manchukuo, China,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, the

Japanese protectorate of Korea and Japanese-claimed territory such as

South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

.

Mexico provided some air support in the form of the

201st Fighter Squadron and

Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

sent naval support in the form of and later the . Most Latin American countries however had little to no involvement, including ones with an island presence in the Pacific, such as Chile, who administer

Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

and several other Pacific islands, and Ecuador, who administer the

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands ( Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuad ...

. All these islands were unaffected by the war.

Axis powers and aligned states

The

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

-aligned states which assisted

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

included the authoritarian government of

Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, which formed a cautious alliance with the Japanese in 1941, when Japanese forces issued the government with an ultimatum following the

Japanese invasion of Thailand

The Japanese invasion of Thailand ( th, การบุกครองไทยของญี่ปุ่น, ; ja, 日本軍のタイ進駐 , Nihongun no Tai shinchū) occurred on 8 December 1941. It was briefly fought between the Kingdo ...

. The leader of Thailand,

Plaek Phibunsongkhram

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram ( th, แปลก พิบูลสงคราม ; alternatively transcribed as ''Pibulsongkram'' or ''Pibulsonggram''; 14 July 1897 – 11 June 1964), locally known as Marshal P. ( th, จอมพล � ...

, became greatly enthusiastic about the alliance after decisive Japanese victories in the

Malayan campaign

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles betwe ...

and in 1942 sent the

Phayap Army

Phayap Army ( th, กองทัพพายัพ RTGS: Thap Phayap or Payap, ''northwest'') was the Thai force that invaded the Siamese Shan States (present day Shan State, Myanmar) of Burma on 10 May 1942 during the Burma Campaign of World ...

to assist the

invasion of Burma, where former Thai territory that had been annexed by Britain

were reoccupied (

Occupied Malayan regions were similarly reintegrated into Thailand in 1943). The Allies supported and organized an underground anti-Japanese resistance group, known as the

Free Thai Movement

The Free Thai Movement ( th, เสรีไทย; ) was a Thai underground resistance movement against Imperial Japan during World War II. Seri Thai were an important source of military intelligence for the Allies in the region.

Background

I ...

, after the Thai ambassador to the United States had refused to hand over the declaration of war. Because of this, after the surrender in 1945, the stance of the United States was that Thailand should be treated as a puppet of Japan and be considered an occupied nation rather than as an ally. This was done in contrast to the British stance towards Thailand, who had faced them in combat as they invaded British territory, and the United States had to block British efforts to impose a punitive peace.

Also involved were members of the

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

, which included the

Manchukuo Imperial Army

The Manchukuo Imperial Army ( zh, s=滿洲國軍, p=Mǎnzhōuguó jūn) was the ground force of the military of the Empire of Manchukuo, a puppet state established by Imperial Japan in Manchuria, a region of northeastern China. The force was pri ...

and

Collaborationist Chinese Army of the Japanese

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

s of

Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

(consisting of most of

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

), and the collaborationist

Wang Jingwei regime

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the pu ...

(which controlled the coastal regions of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

), respectively. In the

Burma campaign, other members, such as the anti-British

Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a collaborationist armed force formed by Indian collaborators and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. Its aim was to secure In ...

of

Free India and the

Burma National Army

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), was a collaborationist and revolutionary army that fought for the end of British rule in Burma by assisting the Japanese in their conquest of the country in 1942 during World War II. It was the first post-c ...

of the

State of Burma

The State of Burma (; ja, ビルマ国, ''Biruma-koku'') was a Japanese puppet state created by Japan in 1943 during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II.

Background

During the early stages of World War II, the Empire of Japan in ...

were active and fighting alongside their Japanese allies.

Moreover, Japan conscripted many soldiers from

its colonies of

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

. Collaborationist security units were also formed in

Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

(reformed ex-colonial

police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

),

Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

(also a member of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

(the

PETA

Peta or PETA may refer to:

Acronym

* Pembela Tanah Air, a militia established by the occupying Japanese in Indonesia in 1943

* People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, an American animal rights organization

* People Eating Tasty Animals, a ...

),

British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. ...

,

British Borneo

British Borneo comprised the four northern parts of the island of Borneo, which are now the country of Brunei, two Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, and the Malaysian federal territory of Labuan. During the British colonial rule before Wor ...

, former

French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

(after

the overthrow of the French regime in 1945) (the

Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

had previously allowed the Japanese to use bases in French Indochina beginning in 1941,

following an invasion) as well as

Timorese militia. These units assisted the Japanese war effort in their respective territories.

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

both had limited involvement in the Pacific War. The

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and the

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

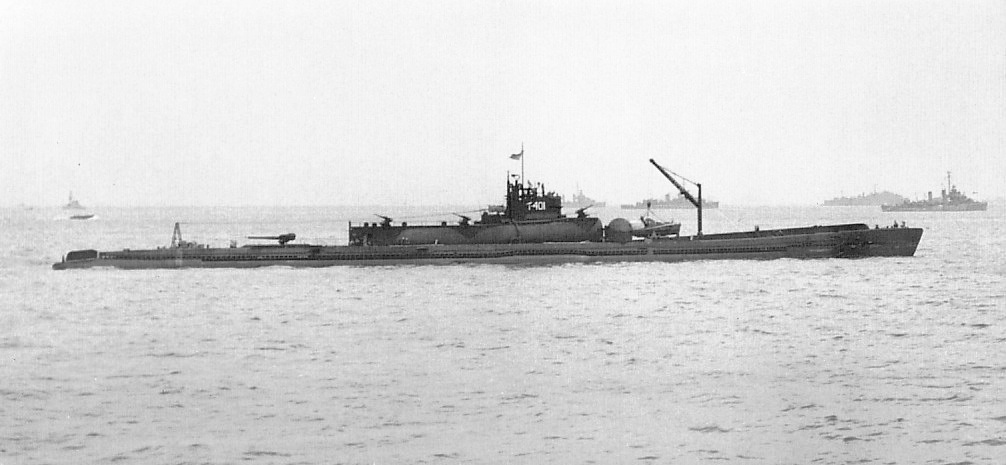

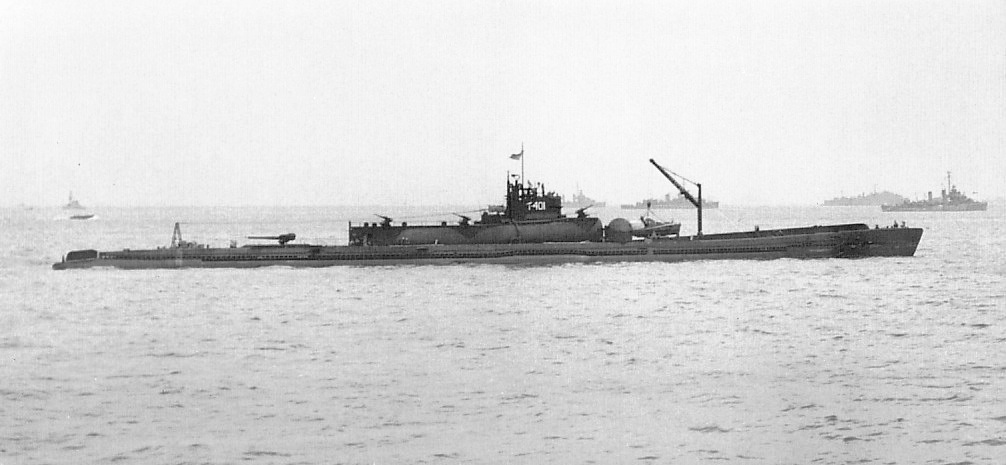

navies operated submarines and

raiding ships in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, notably the

Monsun Gruppe

The ''Gruppe Monsun'' or Monsoon Group was a force of German U-boats (submarines) that operated in the Pacific and Indian Oceans during World War II. Although similar naming conventions were used for temporary groupings of submarines in the At ...

. The Italians had access to

concession territory

In international relations, a concession is a " synallagmatic act by which a State transfers the exercise of rights or functions proper to itself to a foreign private test which, in turn, participates in the performance of public functions and th ...

naval bases in China which they utilized (and which was later ceded to

collaborationist China by the

Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

in late 1943). After Japan's

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

and the subsequent declarations of war, both navies had access to Japanese naval facilities.

Theaters

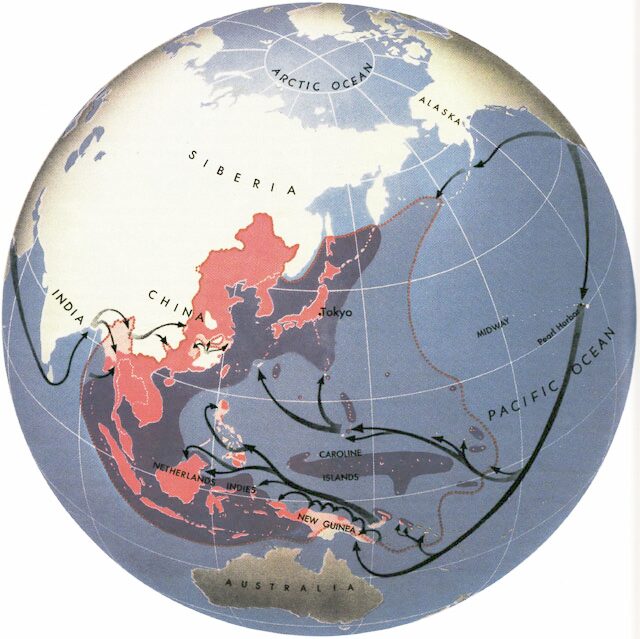

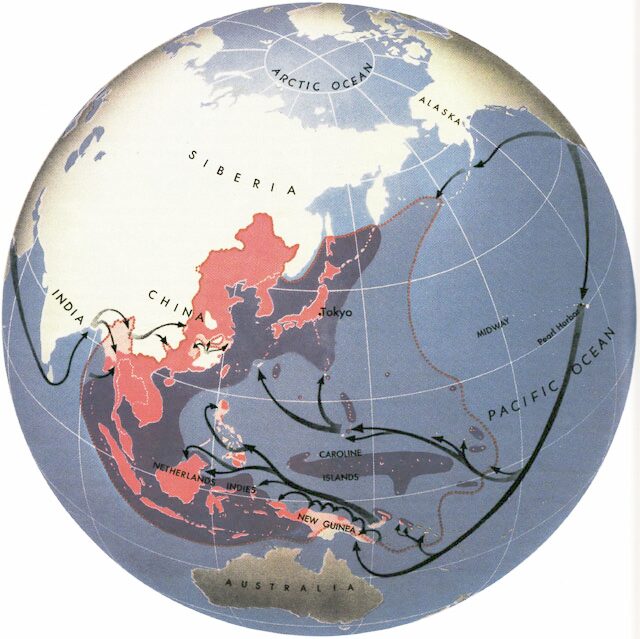

Between 1942 and 1945, there were four main

areas of conflict in the Pacific War:

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, the

Central Pacific,

South-East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

and the

South West Pacific

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million as of ...

. US sources refer to two theaters within the Pacific War: the Pacific theater and the

China Burma India Theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was offi ...

(CBI). However these were not operational commands.

In the Pacific, the Allies divided operational control of their forces between two supreme commands, known as

Pacific Ocean Areas

Pacific Ocean Areas was a major Allied military command in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands during the Pacific War, and one of three United States commands in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. Admir ...

and

Southwest Pacific Area

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the ...

. In 1945, for a brief period just before the

Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

Japanese forces in

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

and

northeast China

Northeast China or Northeastern China () is a geographical region of China, which is often referred to as "Manchuria" or "Inner Manchuria" by surrounding countries and the West. It usually corresponds specifically to the three provinces east of ...

.

The

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

did not integrate its units into permanent theater commands. The

Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

, which had already created the

Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

to oversee its occupation of

Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

and the

China Expeditionary Army

The was a general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1939 to 1945.

The China Expeditionary Army was established in September 1939 from the merger of the Central China Expeditionary Army and Japanese Northern China Area Army, and was headq ...

during the Second Sino-Japanese War, created the

Southern Expeditionary Army Group

''Nanpō gun''

, image = 1938 terauchi hisaichi.jpg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = Japanese General Count Terauchi Hisaichi, right, commanding officer of the Southern Expedition ...

at the outset of its conquests of South East Asia. This headquarters controlled the bulk of the Japanese Army formations which opposed the Western Allies in the Pacific and South East Asia.

Historical background

Conflict between China and Japan

In 1931, without declaring war,

Japan invaded Manchuria, seeking raw materials to fuel its growing industrial economy. By 1937, Japan controlled

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

and it was also ready to move deeper into China. The

Marco Polo Bridge Incident

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident () or the July 7 Incident (), was a July 1937 battle between China's National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army.

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuri ...

on 7 July 1937 provoked full-scale war between China and Japan. The

Nationalist Party and the

Chinese Communists

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

suspended

their civil war in order to form a

nominal alliance against Japan, and the Soviet Union quickly

lent support by providing large amounts of materiel to Chinese troops. In August 1937, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek deployed his best army to fight about 300,000 Japanese troops

in Shanghai, but, after three months of fighting, Shanghai fell. The Japanese continued to push the Chinese forces back,

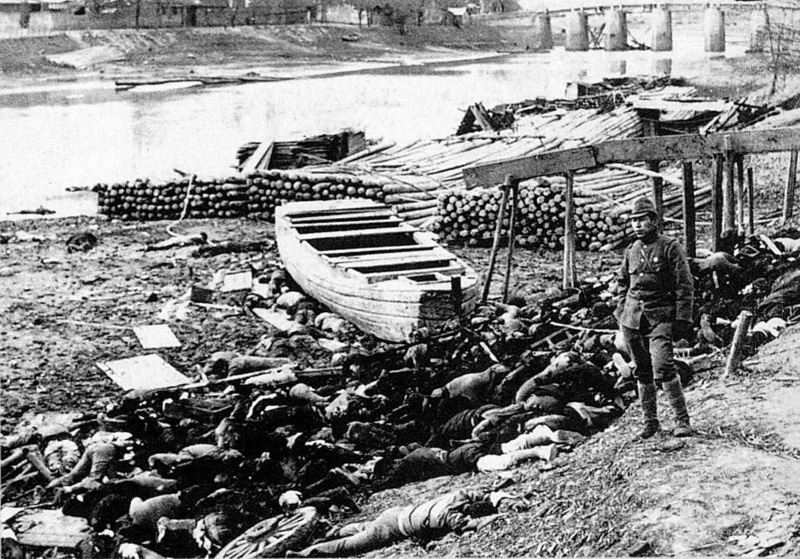

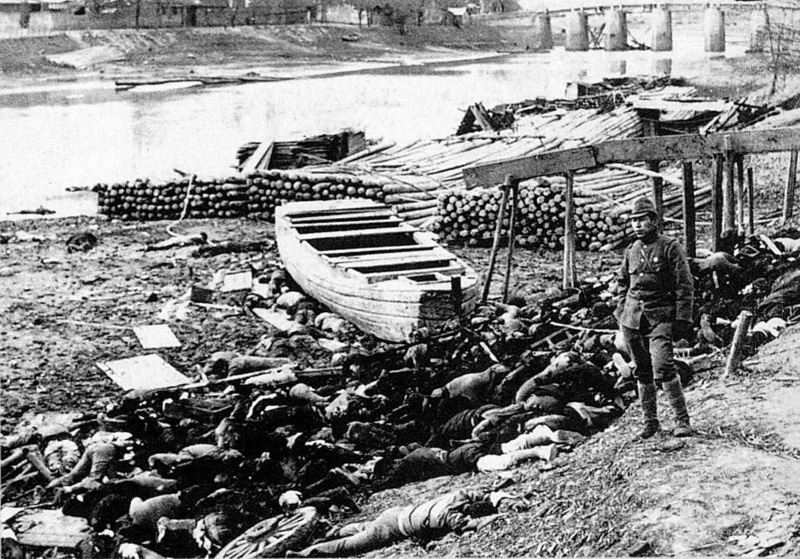

capturing the capital Nanjing in December 1937 and conducted the

Nanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

. In March 1938, Nationalist forces won their

first victory at Taierzhuang, but then the city of

Xuzhou was taken by the Japanese in May. In June 1938, Japan deployed about 350,000 troops to

invade Wuhan and captured it in October. The Japanese achieved major military victories, but world opinion—in particular in the United States—condemned Japan, especially after the

''Panay'' incident.

In 1939, Japanese forces tried to push into the

Soviet Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admini ...

from Manchuria. They were soundly defeated in the

Battle of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, ...

by a mixed Soviet and Mongolian force led by

Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

. This stopped Japanese

expansion to the north, and Soviet aid to China ended as a result of the signing of the

Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

at the beginning of

its war against Germany.

In September 1940, Japan decided to cut China's only land line to the outside world by seizing French Indochina, which was controlled at the time by

Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

. Japanese forces broke their agreement with the Vichy administration and

fighting broke out, ending in a Japanese victory. On 27 September Japan signed a military alliance with Germany and Italy, becoming one of the three main

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. In practice, there was little coordination between Japan and Germany until 1944, by which time the US was deciphering their secret diplomatic correspondence.

The war entered a new phase with the unprecedented defeat of the Japanese at the

Battle of Suixian–Zaoyang

The Battle of Suixian–Zaoyang (), also known as the Battle of Suizao was one of the 22 major engagements between the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) and Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Japanese launched a ...

,

1st Battle of Changsha,

Battle of Kunlun Pass

The Battle of Kunlun Pass () was a series of conflicts between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Chinese forces surrounding Kunlun Pass, a key strategic position in Guangxi province. The Japanese forces planned to cut off Chinese supply lines ...

and

Battle of Zaoyi

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

. After these victories, Chinese nationalist forces launched a large-scale

counter-offensive

In the study of military tactics, a counter-offensive is a large-scale strategic offensive military operation, usually by forces that had successfully halted the enemy's offensive, while occupying defensive positions.

The counter-offensive ...

in early 1940; however, due to its low military-industrial capacity, it was repulsed by the Imperial Japanese Army in late March 1940. In August 1940,

Chinese communists

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

launched an

offensive in Central China; in retaliation, Japan instituted the "

Three Alls Policy

The Three Alls Policy (, ja, 三光作戦 Sankō Sakusen) was a Japanese scorched earth policy adopted in China during World War II, the three "alls" being . This policy was designed as retaliation against the Chinese for the Communist-led Hundr ...

" ("Kill all, Burn all, Loot all") in occupied areas to reduce human and material resources for the communists.

By 1941 the conflict had become a stalemate. Although Japan had occupied much of northern, central, and coastal China, the

Nationalist Government had retreated to the interior with a provisional capital set up at

Chungking

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Coun ...

while the Chinese communists remained in control of base areas in

Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

. In addition, Japanese control of northern and central China was somewhat tenuous, in that Japan was usually able to control railroads and the major cities ("points and lines"), but did not have a major military or administrative presence in the vast Chinese countryside. The Japanese found its aggression against the retreating and regrouping Chinese army was stalled by the mountainous terrain in southwestern China while the Communists organised widespread

guerrilla and saboteur activities in northern and eastern China behind the Japanese front line.

Japan sponsored several

puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

s, one of which was headed by

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

. However, its policies of brutality toward the Chinese population, of not yielding any real power to these regimes, and of supporting several rival governments failed to make any of them a viable alternative to the Nationalist government led by

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. Conflicts between Chinese Communist and Nationalist forces vying for territory control behind enemy lines

culminated in a major armed clash in January 1941, effectively ending their co-operation.

Japanese

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

efforts mostly targeted large Chinese cities such as Shanghai,

Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

, and

Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Co ...

, with around 5,000 raids from February 1938 to August 1943 in the later case. Japan's strategic bombing campaigns devastated Chinese cities extensively, killing 260,000–350,934

non-combatant

Non-combatant is a term of art in the law of war and international humanitarian law to refer to civilians who are not taking a direct part in hostilities; persons, such as combat medics and military chaplains, who are members of the belligere ...

s.

Tensions between Japan and the West

From as early as 1935, Japanese military strategists had concluded the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

were, because of their oil reserves, of considerable importance to Japan. By 1940 they had expanded this to include Indochina, Malaya, and the Philippines within their concept of the

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

. Japanese troop build ups in Hainan, Taiwan, and

Haiphong

Haiphong ( vi, Hải Phòng, ), or Hải Phòng, is a major industrial city and the third-largest in Vietnam. Hai Phong is also the center of technology, economy, culture, medicine, education, science and trade in the Red River delta.

Haiphong wa ...

were noted, Imperial Japanese Army officers were openly talking about an inevitable war, and Admiral

Sankichi Takahashi was reported as saying a showdown with the United States was necessary.

In an effort to discourage Japanese militarism, Western powers including Australia, the United States, Britain, and the

Dutch government in exile

The Dutch government-in-exile ( nl, Nederlandse regering in ballingschap), also known as the London Cabinet ( nl, Londens kabinet), was the government in exile of the Netherlands, supervised by Queen Wilhelmina, that fled to London after the Ger ...

, which controlled the petroleum-rich Dutch East Indies,

stopped selling oil, iron ore, and steel to Japan, denying it the raw materials needed to continue its activities in China and French Indochina. In Japan, the government and

nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

viewed these embargoes as acts of aggression; imported oil made up about 80% of domestic consumption, without which Japan's economy, let alone its military, would grind to a halt. The Japanese media, influenced by military propagandists, began to refer to the embargoes as the "ABCD ("American-British-Chinese-Dutch") encirclement" or "

ABCD line

The was a Japanese name for a series of embargoes against Japan by foreign nations, including the United States of America, Britain, China, and the Dutch. It was also known as the . In 1940, in an effort to discourage Japanese militarism, thes ...

".

Faced with a choice between economic collapse and withdrawal from its recent conquests (with its attendant loss of face), the Japanese

Imperial General Headquarters

The was part of the Supreme War Council and was established in 1893 to coordinate efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during wartime. In terms of function, it was approximately equivalent to the United States ...

(GHQ) began planning for a war with the Western powers in April or May 1941.

Japanese preparations

In preparation for the war against the United States, which would be decided at sea and in the air, Japan increased its naval budget as well as putting large formations of the Army and its attached air force under navy command. While formerly the IJA consumed the lion's share of the state's military budget due to the secondary role of the IJN in Japan's campaign against China (with a 73/27 split in 1940), from 1942 to 1945 there would instead be a roughly 60/40 split in funds between the army and the navy. Japan's key objective during the initial part of the conflict was to seize economic resources in the Dutch East Indies and

Malaya which offered Japan a way to escape the effects of the Allied embargo. This was known as the

Southern Plan. It was also decided—because of the close relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States,

[Willmott, ''Barrier and the Javelin'' (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1983).] and the (mistaken)

[ belief that the US would inevitably become involved—that Japan would also require taking the Philippines, Wake and ]Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

.

Japanese planning was for fighting a limited war where Japan would seize key objectives and then establish a defensive perimeter to defeat Allied counterattacks, which in turn would lead to a negotiated peace.

The attack on the US Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

, Hawaii, by carrier

Carrier may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Carrier'' (album), a 2013 album by The Dodos

* ''Carrier'' (board game), a South Pacific World War II board game

* ''Carrier'' (TV series), a ten-part documentary miniseries that aired on PBS in April 20 ...

-based aircraft of the Combined Fleet

The was the main sea-going component of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Until 1933, the Combined Fleet was not a permanent organization, but a temporary force formed for the duration of a conflict or major naval maneuvers from various units norm ...

was intended to give the Japanese time to complete a perimeter.

The early period of the war was divided into two operational phases. The First Operational Phase was further divided into three separate parts in which the major objectives of the Philippines, British Malaya, Borneo, Burma, Rabaul and the Dutch East Indies would be occupied. The Second Operational Phase called for further expansion into the South Pacific by seizing eastern New Guinea, New Britain, Fiji, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area. In the Central Pacific, Midway was targeted as were the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific. Seizure of these key areas would provide defensive depth and deny the Allies staging areas from which to mount a counteroffensive.

By November these plans were essentially complete, and were modified only slightly over the next month. Japanese military planners' expectation of success rested on the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union being unable to effectively respond to a Japanese attack because of the threat posed to each by Germany; the Soviet Union was even seen as unlikely to commence hostilities.

The Japanese leadership was aware that a total military victory in a traditional sense against the US was impossible; the alternative would be negotiating for peace after their initial victories, which would recognize Japanese hegemony in Asia.[Boog et al. (2006) "Germany and the Second World War: The Global War", p. 175] In fact, the Imperial GHQ noted, should acceptable negotiations be reached with the Americans, the attacks were to be canceled—even if the order to attack had already been given. The Japanese leadership looked to base the conduct of the war against America on the historical experiences of the successful wars against China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–05), in both of which a strong continental power was defeated by reaching limited military objectives, not by total conquest.

Japanese offensives, 1941–42

Following prolonged tensions between Japan and the Western powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. , units of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

and Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

launched simultaneous surprise attack

Military deception (MILDEC) is an attempt by a military unit to gain an advantage during warfare by misleading adversary decision makers into taking action or inaction that creates favorable conditions for the deceiving force. This is usually ac ...

s on the United States and the British Empire on 7 December (8 December in Asia/West Pacific time zones). The locations of this first wave of Japanese attacks included the American territories of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, and Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

and the British territories of Malaya, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

. Concurrently, Japanese forces invaded southern and eastern Thailand and were resisted for several hours, before the Thai government

The Government of Thailand, or formally the Royal Thai Government ( Abrv: RTG; th, รัฐบาลไทย, , ), is the unitary government of the Kingdom of Thailand. The country emerged as a modern nation state after the foundation of t ...

signed an armistice and entered an alliance with Japan. Although Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire, the declaration was not delivered until after the attacks began.

Subsequent attacks and invasions followed during December 1941 and early 1942 leading to the occupation of American, British, Dutch and Australian territories and air raids on the Australian mainland. The Allies suffered many disastrous defeats in the first six months of the war.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

In the early hours of 7 December (Hawaiian time), Japan launched a major surprise carrier-based air strike on Pearl Harbor in Honolulu without explicit warning, which crippled the US Pacific Fleet, left eight American battleships out of action, destroyed 188 American aircraft, and caused the deaths of 2,403 Americans. The Japanese had gambled that the United States, when faced with such a sudden and massive blow and loss of life, would agree to a negotiated settlement and allow Japan free rein in Asia. This gamble did not pay off. American losses were less serious than initially thought: the three American aircraft carriers, which would prove to be more important than battleships, were at sea, and vital naval infrastructure (fuel oil tanks, shipyard facilities, and a power station), submarine base, and signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of '' signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ...

units were unscathed, and the fact the bombing happened while the US was not officially at war anywhere in the world caused a wave of outrage across the United States. Japan's fallback strategy, relying on a war of attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies fro ...

to make the US come to terms, was beyond the IJN's capabilities.[Parillo, Mark P. ''Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II''. (United States Naval Institute Press, 1993).]

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 800,000-member America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

vehemently opposed any American intervention in the European conflict, even as America sold military aid to Britain and the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program. Opposition to war in the US vanished after the attack. On 8 December, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands declared war on Japan, followed by ChinaGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

declared war on the United States, drawing the country into a two-theater war. This is widely agreed to be a grand strategic blunder, as it abrogated both the benefit Germany gained by Japan's distraction of the US and the reduction in aid to Britain, which both Congress and Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had managed to avoid during over a year of mutual provocation, which would otherwise have resulted.

South-East Asian campaigns of 1941–42

Thailand, with its territory already serving as a springboard for the Malayan Campaign

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles betwe ...

, surrendered within 5 hours of the Japanese invasion.Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

had seized the British colony of Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the M ...

on 19 December, encountering little resistance.Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

and Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

were lost at around the same time. British, Australian, and Dutch forces, already drained of personnel and matériel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specif ...

by two years of war with Germany, and heavily committed in the Middle East, North Africa, and elsewhere, were unable to provide much more than token resistance to the battle-hardened Japanese. Two major British warships, the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

and the battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

, were sunk by a Japanese air attack off Malaya on 10 December 1941.

Following the Declaration by United Nations

The Declaration by United Nations was the main treaty that formalized the Allies of World War II and was signed by 47 national governments between 1942 and 1945. On 1 January 1942, during the Arcadia Conference, the Allied " Big Four"—the Unite ...

(the first official use of the term United Nations) on 1 January 1942, the Allied governments appointed the British General Sir Archibald Wavell

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded i ...

to the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was a short-lived, supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consists of the forces of Aust ...

(ABDACOM), a supreme command for Allied forces in Southeast Asia. This gave Wavell nominal control of a huge force, albeit thinly spread over an area from Burma to the Philippines to northern Australia. Other areas, including India, Hawaii, and the rest of Australia remained under separate local commands. On 15 January, Wavell moved to Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

to assume control of ABDACOM.

In January, Japan invaded British Burma, the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and captured Manila, Kuala Lumpur and

In January, Japan invaded British Burma, the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and captured Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

. After being driven out of Malaya, Allied forces in Singapore attempted to resist the Japanese during the Battle of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire of ...

, but were forced to surrender to the Japanese on 15 February 1942; about 130,000 Indian, British, Australian and Dutch personnel became prisoners of war. The pace of conquest was rapid: Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and ...

and Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western part. The Indonesian part, ...

also fell in February.[ See ]Battle of Timor

The Battle of Timor occurred in Portuguese Timor and Dutch Timor during the Second World War. Japanese forces invaded the island on 20 February 1942 and were resisted by a small, under-equipped force of Allied military personnel—known as ...

. The rapid collapse of Allied resistance left the "ABDA area" split in two. Wavell resigned from ABDACOM on 25 February, handing control of the ABDA Area to local commanders and returning to the post of Commander-in-Chief, India

During the period of the Company rule in India and the British Raj, the Commander-in-Chief, India (often "Commander-in-Chief ''in'' or ''of'' India") was the supreme commander of the British Indian Army. The Commander-in-Chief and most of his ...

.

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in Southeast Asia and were making air attacks on northern Australia, beginning with a psychologically devastating but militarily insignificant bombing of the city of Darwin on 19 February, which killed at least 243 people.

At the

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in Southeast Asia and were making air attacks on northern Australia, beginning with a psychologically devastating but militarily insignificant bombing of the city of Darwin on 19 February, which killed at least 243 people.

At the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea ( id, Pertempuran Laut Jawa, ja, スラバヤ沖海戦, Surabaya oki kaisen, Surabaya open-sea battle, Javanese : ꦥꦼꦫꦁꦱꦼꦒꦫꦗꦮ, romanized: ''Perang Segara Jawa'') was a decisive naval battle o ...

in late February and early March, the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) inflicted a resounding defeat on the main ABDA naval force, under Admiral Karel Doorman

Karel Willem Frederik Marie Doorman (23 April 1889 – 28 February 1942) was a Dutch naval officer who during World War II commanded remnants of the short-lived American-British-Dutch-Australian Command naval strike forces in the Battle ...

.Dutch East Indies campaign

The Dutch East Indies campaign of 1941–1942 was the conquest of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) by forces from the Empire of Japan in the early days of the Pacific campaign of World War II. Forces from the Allies attempted u ...

subsequently ended with the surrender of Allied forces on Java and Sumatra.Moulmein

Mawlamyine (also spelled Mawlamyaing; , ; th, เมาะลำเลิง ; mnw, မတ်မလီု, ), formerly Moulmein, is the fourth-largest city in Myanmar (Burma), ''World Gazetteer'' south east of Yangon and south of Thaton, at th ...

on 31 January 1942, and then drove outnumbered British and Indian troops towards the Sittang River

The Sittaung River ( my, စစ်တောင်းမြစ် ; formerly, the Sittang or Sittounghttps://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/UNGEGN/docs/8th-uncsgn-docs/inf/8th_UNCSGN_econf.94_INF.75.pdf ) is a river in south central Myanmar in Bago ...

. On 23 February, a bridge over the river was demolished prematurely, stranding most of an Indian division on the far side. On 8 March, the Japanese occupied Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

, although they missed a chance to trap the remnants of the Burma Army within the city. The allies then tried to defend Central Burma, with Indian and Burmese divisions holding the Irrawaddy River

The Irrawaddy River ( Ayeyarwady River; , , from Indic ''revatī'', meaning "abounding in riches") is a river that flows from north to south through Myanmar (Burma). It is the country's largest river and most important commercial waterway. Orig ...

valley and the Chinese Expeditionary Force in Burma defending Toungoo

Taungoo (, ''Tauñngu myoú''; ; also spelled Toungoo) is a district-level city in the Bago Region of Myanmar, 220 km from Yangon, towards the north-eastern end of the division, with mountain ranges to the east and west. The main industry ...

, south of Mandalay. On 16 April, 7,000 British soldiers were encircled by the Japanese 33rd Division during the Battle of Yenangyaung

The Battle of Yenangyaung () was fought in Burma, now Myanmar, during the Burma Campaign in World War II. The battle of Yenaungyaung was fought in the vicinity of Yenangyaung and its oil fields.

Background

After the Japanese captured Rangoon in ...

and rescued by the Chinese 38th Division, led by Sun Li-jen

Sun Li-jen (; December 8, 1900November 19, 1990) was a Chinese Nationalist (KMT) general, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, best known for his leadership in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. His military achiev ...

. Meanwhile, in the Battle of Yunnan-Burma Road, the Japanese captured Toungoo after a severe battle and sent motorised units to capture Lashio

Lashio ( ; Shan: ) is the largest town in northern Shan State, Myanmar, about north-east of Mandalay. It is situated on a low mountain spur overlooking the valley of the Yaw River. Loi Leng, the highest mountain of the Shan Hills, is located ...

. This cut the Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

, which was the western Allies' supply line to the Chinese Nationalists. Many of the Chinese troops were trapped and were forced either to retreat to India or in small parties to Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

. Accompanied by large numbers of civilian refugees, the British retreated to Imphal

Imphal ( Meitei pronunciation: /im.pʰal/; English pronunciation: ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Manipur. The metropolitan centre of the city contains the ruins of Kangla Palace (also known as Kangla Fort), the royal seat of the f ...