Edward Teller (1958)-LLNL.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

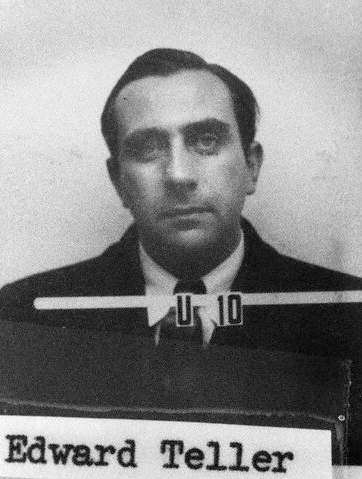

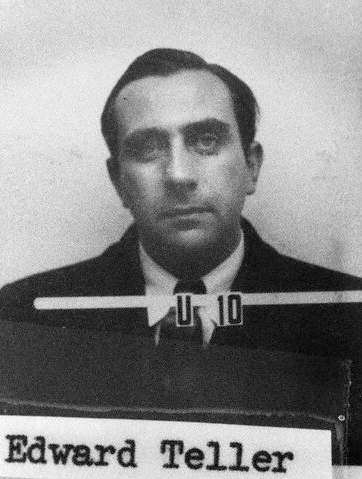

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory ''

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory ''

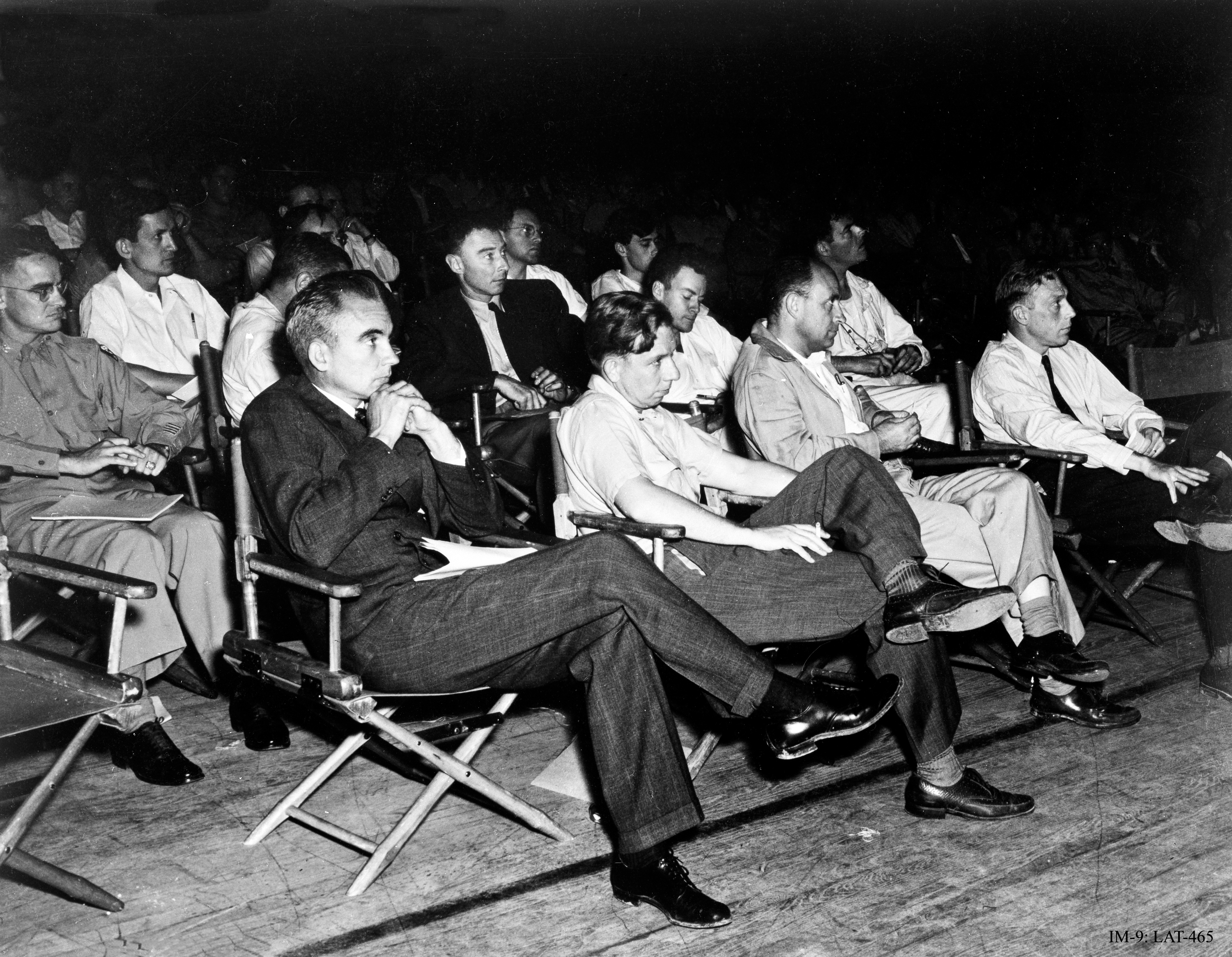

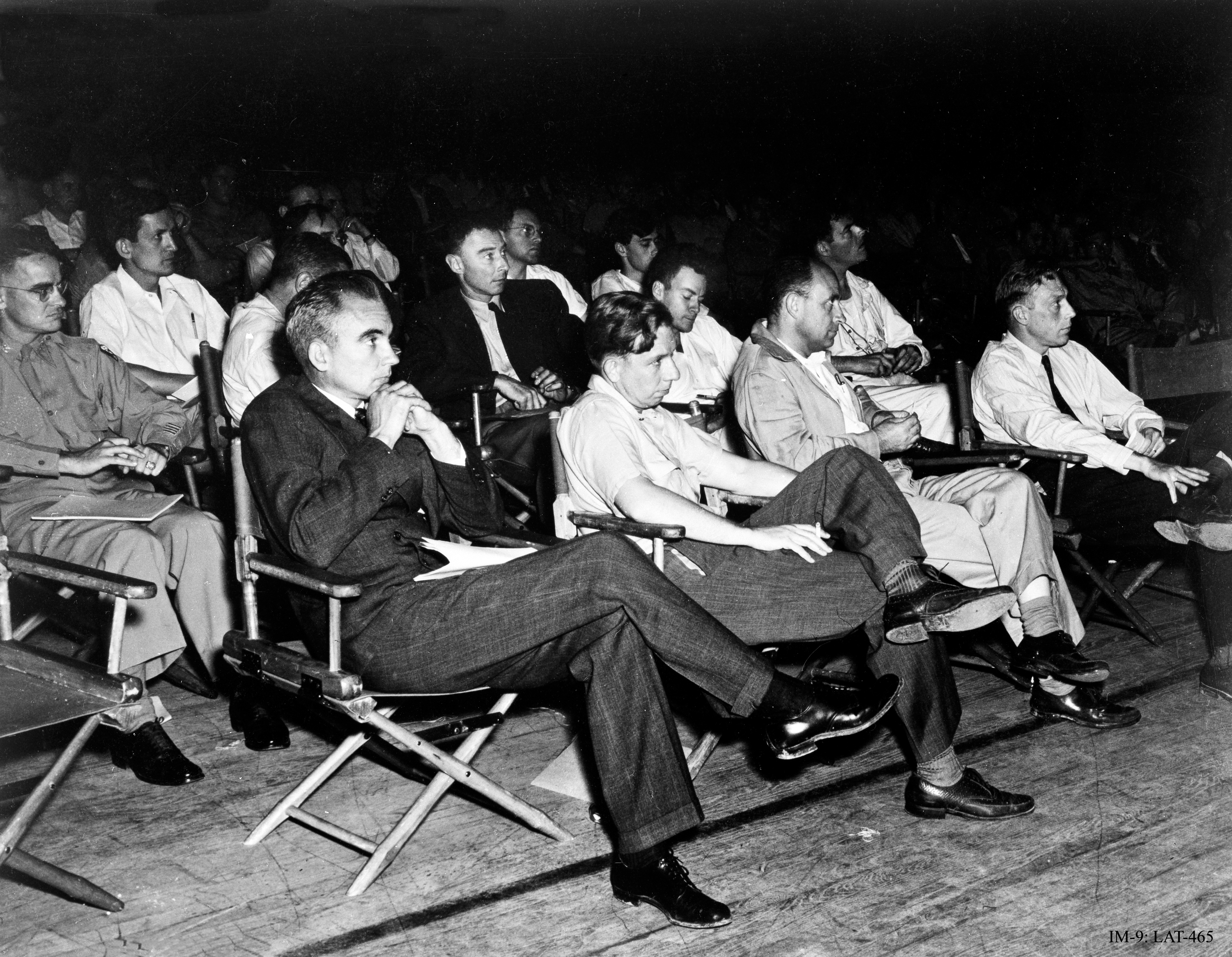

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as  By 1949, Soviet-backed governments had already begun seizing control throughout

By 1949, Soviet-backed governments had already begun seizing control throughout  Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney

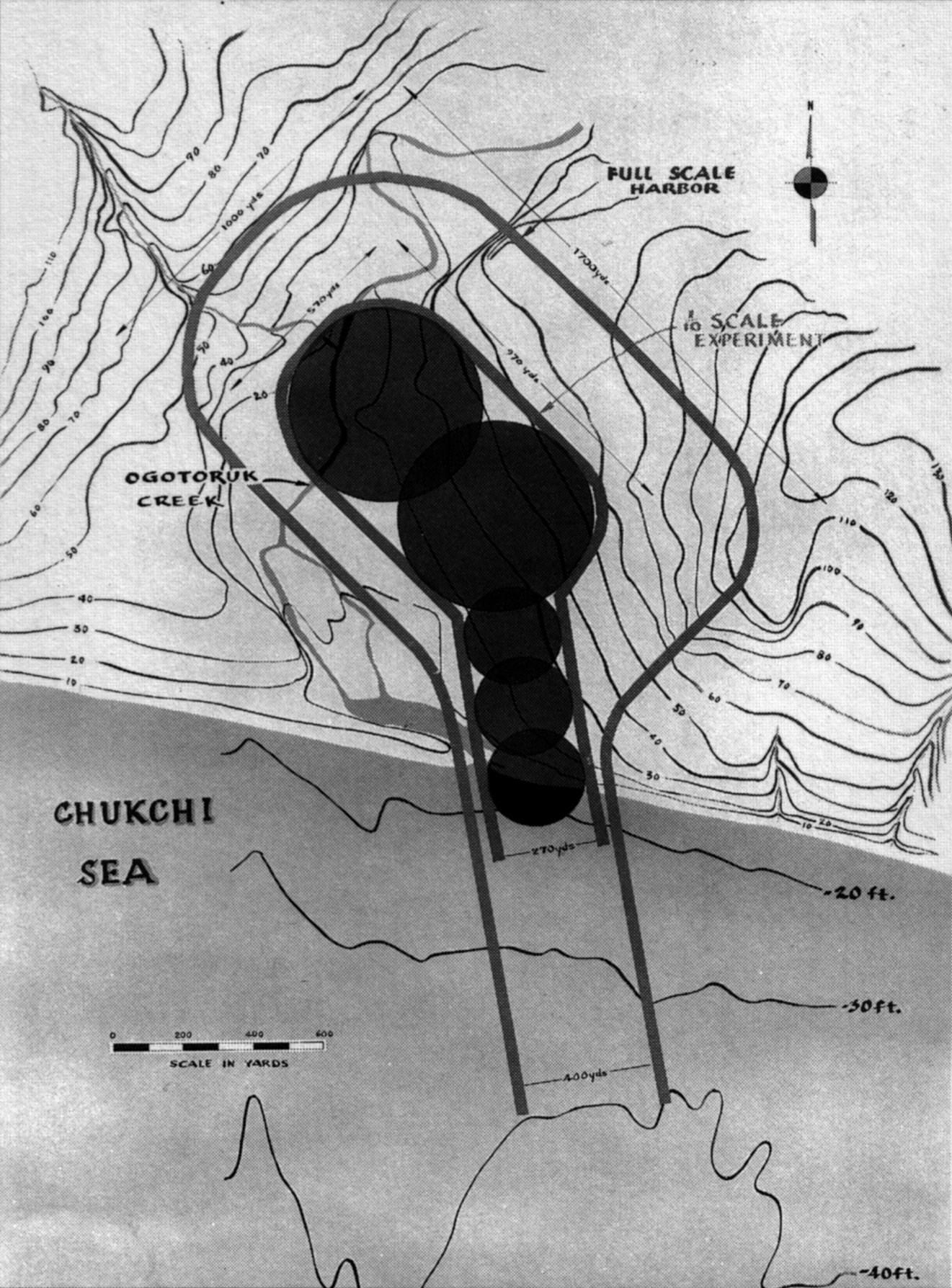

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derided by critics as "Star Wars", the concept of using ground and satellite-based lasers, particle beams and missiles to destroy incoming Soviet ICBMs. Teller lobbied with government agencies—and got the approval of President Ronald Reagan—for a plan to develop a system using elaborate

In the 1980s, Teller began a strong campaign for what was later called the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derided by critics as "Star Wars", the concept of using ground and satellite-based lasers, particle beams and missiles to destroy incoming Soviet ICBMs. Teller lobbied with government agencies—and got the approval of President Ronald Reagan—for a plan to develop a system using elaborate

/ref> In order to safeguard the earth, the theoretical 1 Gt device would weigh about 25–30 tons—light enough to be lifted on the Russian Energia rocket—and could be used to instantaneously vaporize a 1 km asteroid, or divert the paths of extinction event class asteroids (greater than 10 km in diameter) with a few months' notice; with 1-year notice, at an interception location no closer than

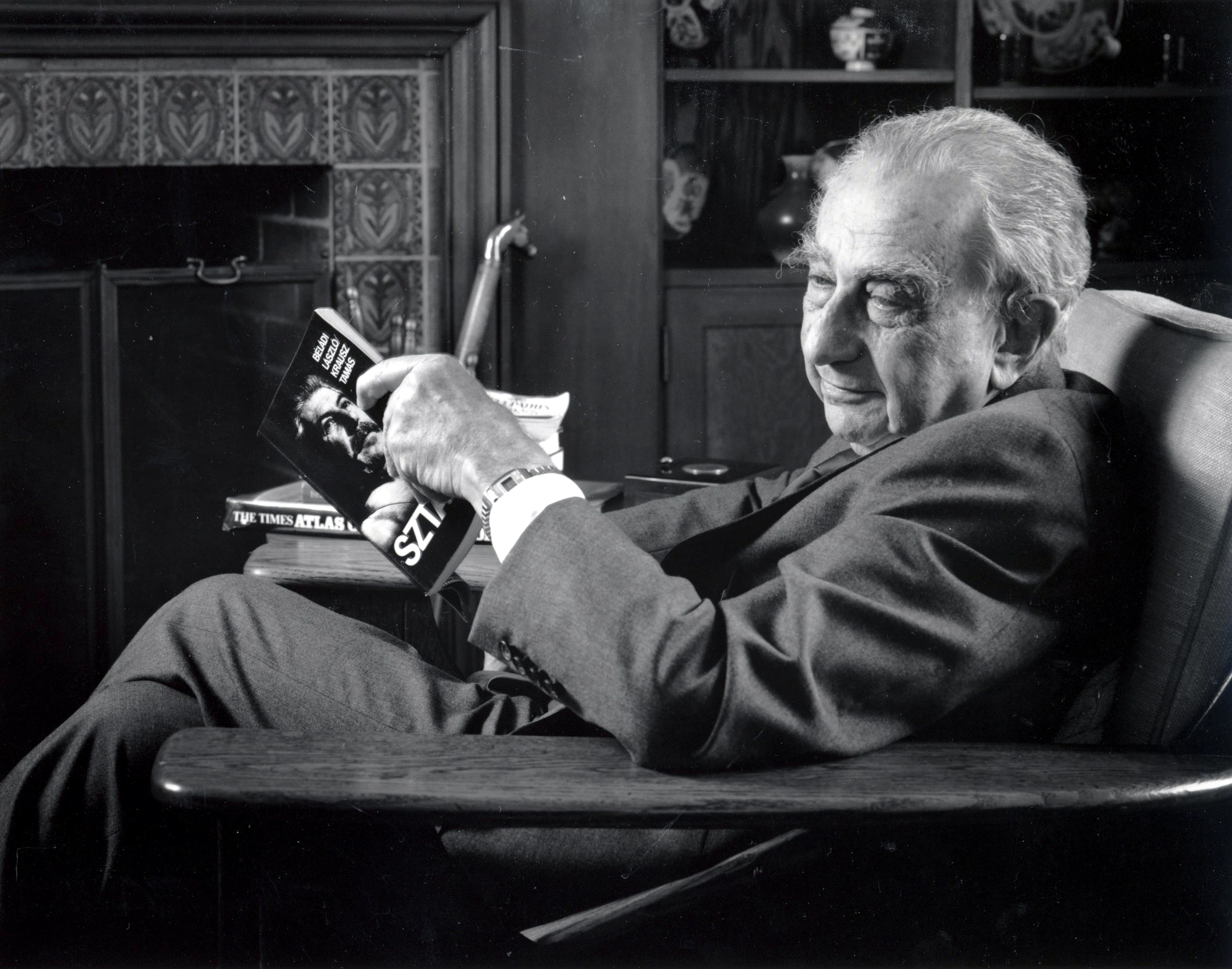

Teller died in

Teller died in

The Constructive Uses of Nuclear Explosions

' (1968) * ''Energy from Heaven and Earth'' (1979) * ''The Pursuit of Simplicity'' (1980) * ''Better a Shield Than a Sword: Perspectives on Defense and Technology'' (1987) * ''Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics'' (1991), with Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley * ''Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics'' (2001), with Judith Shoolery

Russian text (free download)

* * * * * * * * * * *

Science and Technology Review

' contains 10 articles written primarily by Stephen B. Libby in 2007, about Edward Teller's life and contributions to science, to commemorate the 2008 centennial of his birth. * ''Heisenberg Sabotaged the Atomic Bomb'' (''Heisenberg hat die Atombombe sabotiert'') an interview in German with Edward Teller in: Michael Schaaf: ''Heisenberg, Hitler und die Bombe. Gespräche mit Zeitzeugen'' Berlin 2001, . * * Szilard, Leo. (1987) ''Toward a Livable World: Leo Szilard and the Crusade for Nuclear Arms Control''. Cambridge: MIT Press.

1986 Audio Interview with Edward Teller by S. L. Sanger

Voices of the Manhattan Project

Annotated Bibliography for Edward Teller from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

interview with

Edward Teller Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

A radio interview with Edward Teller

Aired on the Lewis Burke Frumkes Radio Show in January 1988.

The Paternity of the H-Bombs: Soviet-American Perspectives

Edward Teller tells his life story at Web of Stories

(video) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Teller, Edward 1908 births 2003 deaths American agnostics American amputees American nuclear physicists American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent Enrico Fermi Award recipients Fasori Gimnázium alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellows of the American Physical Society Founding members of the World Cultural Council George Washington University faculty Hungarian agnostics Hungarian amputees Hungarian emigrants to the United States Hungarian Jews 20th-century Hungarian physicists Members of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science Israeli nuclear development Jewish agnostics Jewish American scientists Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States Jewish physicists Karlsruhe Institute of Technology alumni Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory staff Leipzig University alumni Manhattan Project people Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Medal of Science laureates Nuclear proliferation Scientists from Budapest Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Theoretical physicists University of California, Berkeley faculty University of Chicago faculty University of Göttingen faculty Zionists Time Person of the Year

theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

), although he did not care for the title, considering it to be in poor taste. Throughout his life, Teller was known both for his scientific ability and for his difficult interpersonal relations and volatile personality.

Born in Hungary in 1908, Teller emigrated to the United States in the 1930s, one of the many so-called "Martians", a group of prominent Hungarian scientist émigrés. He made numerous contributions to nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and molecular physics

Molecular physics is the study of the physical properties of molecules and molecular dynamics. The field overlaps significantly with physical chemistry, chemical physics, and quantum chemistry. It is often considered as a sub-field of atomic, m ...

, spectroscopy (in particular the Jahn–Teller and Renner–Teller effects), and surface physics. His extension of Enrico Fermi's theory of beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For ...

, in the form of Gamow–Teller transitions, provided an important stepping stone in its application, while the Jahn–Teller effect and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory have retained their original formulation and are still mainstays in physics and chemistry.

Teller also made contributions to Thomas–Fermi theory, the precursor of density functional theory

Density-functional theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used in physics, chemistry and materials science to investigate the electronic structure (or nuclear structure) (principally the ground state) of many-body ...

, a standard modern tool in the quantum mechanical

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, qua ...

treatment of complex molecules. In 1953, along with Nicholas Metropolis

Nicholas Constantine Metropolis (Greek: ; June 11, 1915 – October 17, 1999) was a Greek-American physicist.

Metropolis received his BSc (1937) and PhD in physics (1941, with Robert Mulliken) at the University of Chicago. Shortly afterwards, ...

, Arianna Rosenbluth, Marshall Rosenbluth, and his wife Augusta Teller, Teller co-authored a paper that is a standard starting point for the applications of the Monte Carlo method

Monte Carlo methods, or Monte Carlo experiments, are a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. The underlying concept is to use randomness to solve problems that might be determi ...

to statistical mechanics and the Markov chain Monte Carlo

In statistics, Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods comprise a class of algorithms for sampling from a probability distribution. By constructing a Markov chain that has the desired distribution as its equilibrium distribution, one can obtain ...

literature in Bayesian statistics

Bayesian statistics is a theory in the field of statistics based on the Bayesian interpretation of probability where probability expresses a ''degree of belief'' in an event. The degree of belief may be based on prior knowledge about the event, ...

. Teller was an early member of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, charged with developing the first atomic bomb. He made a serious push to develop the first fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

-based weapons as well, but these were deferred until after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. He co-founded the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and was both its director and associate director for many years. After his controversial negative testimony in the Oppenheimer security hearing

The Oppenheimer security hearing was a 1954 proceeding by the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that explored the background, actions, and associations of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American scientist who had headed the Los Alamos Lab ...

convened against his former Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

superior, J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is oft ...

, Teller was ostracized by much of the scientific community.

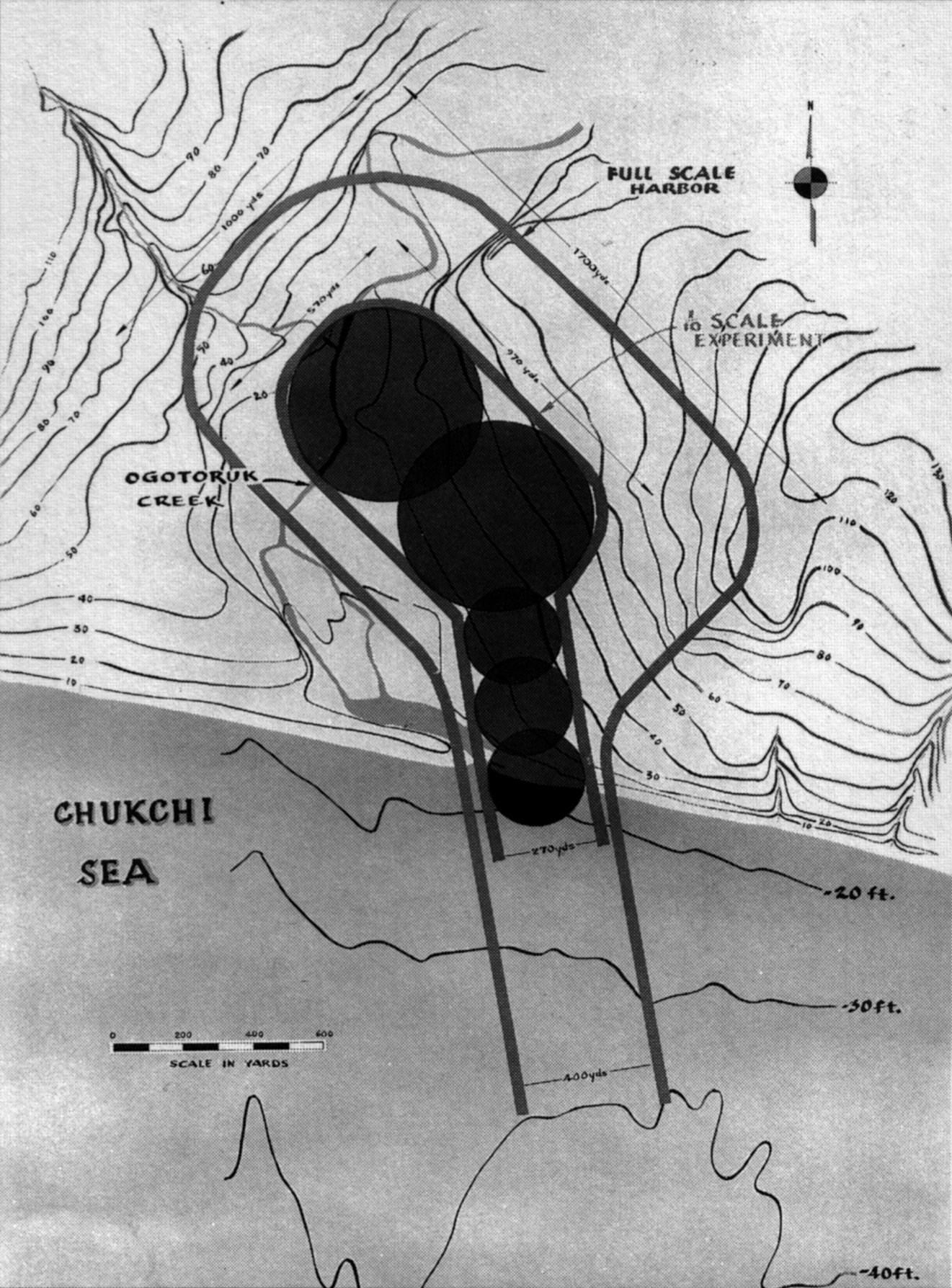

Teller continued to find support from the U.S. government and military research establishment, particularly for his advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program. In his later years, he became especially known for his advocacy of controversial technological solutions to both military and civilian problems, including a plan to excavate an artificial harbor in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

using thermonuclear

Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or “fusing” using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible. There are two forms of thermonuclear fusion: ''uncontrolled'', in which the re ...

explosive in what was called Project Chariot

Project Chariot was a 1958 US Atomic Energy Commission proposal to construct an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson on the North Slope of the U.S. state of Alaska by burying and detonating a string of nuclear devices.

History

The project o ...

, and Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative. Teller was a recipient of numerous awards, including the Enrico Fermi Award

The Enrico Fermi Award is a scientific award conferred by the President of the United States. It is awarded to honor scientists of international stature for their lifetime achievement in the development, use, or production of energy. It was establ ...

and Albert Einstein Award. He died on September 9, 2003, in Stanford, California

Stanford is a census-designated place (CDP) in the northwest corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States. It is the home of Stanford University. The population was 21,150 at the 2020 census.

Stanford is an unincorporated area of ...

, at 95.

Early life and work

Ede Teller was born on January 15, 1908, inBudapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, into a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

family. His parents were Ilona (née Deutsch), a pianist, and Max Teller, an attorney. He attended the Fasori Lutheran Gymnasium, then in the Lutheran Minta (Model) Gymnasium in Budapest. Of Jewish origin, later in life Teller became an agnostic Jew. "Religion was not an issue in my family", he later wrote, "indeed, it was never discussed. My only religious training came because the Minta required that all students take classes in their respective religions. My family celebrated one holiday, the Day of Atonement

Yom Kippur (; he, יוֹם כִּפּוּר, , , ) is the holiest day in Judaism and Samaritanism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the first month of the Hebrew calendar. Primarily centered on atonement and repentance, the day's o ...

, when we all fasted. Yet my father said prayers for his parents on Saturdays and on all the Jewish holidays. The idea of God that I absorbed was that it would be wonderful if He existed: We needed Him desperately but had not seen Him in many thousands of years." Teller was a late talker

A late talker is a toddler experiencing late language emergence (LLE), which can also be an early or secondary sign of an autism spectrum disorder, or other developmental disorders, such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, attention deficit hypera ...

and developed the ability to speak later than most children, but became very interested in numbers, and would calculate large numbers in his head for fun.

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory ''

Teller left Hungary for Germany in 1926, partly due to the discriminatory ''numerus clausus

''Numerus clausus'' ("closed number" in Latin) is one of many methods used to limit the number of students who may study at a university. In many cases, the goal of the ''numerus clausus'' is simply to limit the number of students to the maximum ...

'' rule under Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya ( hu, Vitéz nagybányai Horthy Miklós; ; English: Nicholas Horthy; german: Nikolaus Horthy Ritter von Nagybánya; 18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957), was a Hungarian admiral and dictator who served as the regent ...

's regime. The political climate and revolutions in Hungary during his youth instilled a lingering animosity for both Communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

in Teller.

From 1926 to 1928, Teller studied mathematics and chemistry at the University of Karlsruhe

The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT; german: Karlsruher Institut für Technologie) is a public research university in Karlsruhe, Germany. The institute is a national research center of the Helmholtz Association.

KIT was created in 2009 w ...

, where he graduated with a bachelor of science in chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials int ...

. He once stated that the person who was responsible for his becoming a physicist was Herman Mark, who was a visiting professor, after hearing lectures on molecular spectroscopy where Mark made it clear to him that it was new ideas in physics that were radically changing the frontier of chemistry. Mark was an expert in polymer chemistry

Polymer chemistry is a sub-discipline of chemistry that focuses on the structures of chemicals, chemical synthesis, and chemical and physical properties of polymers and macromolecules. The principles and methods used within polymer chemistry are a ...

, a field which is essential to understanding biochemistry, and Mark taught him about the leading breakthroughs in quantum physics made by Louis de Broglie

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (, also , or ; 15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French physicist and aristocrat who made groundbreaking contributions to Old quantum theory, quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he pos ...

, among others. It was this exposure which he had gotten from Mark's lectures which motivated Teller to switch to physics. After informing his father of his intent to switch, his father was so concerned that he traveled to visit him and speak with his professors at the school. While a degree in chemical engineering was a sure path to a well-paying job at chemical companies, there was not such a clear-cut route for a career with a degree in physics. He was not privy to the discussions his father had with his professors, but the result was that he got his father's permission to become a physicist.

Teller then attended the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It is Germany's sixth-oldest university in continuous operatio ...

where he studied physics under Arnold Sommerfeld. On July 14, 1928, while still a young student in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, he was taking a streetcar to catch a train for a hike in the nearby Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

and decided to jump off while it was still moving. He fell, and the wheel severed most of his right foot. For the rest of his life, he walked with a permanent limp, and on occasion he wore a prosthetic

In medicine, a prosthesis (plural: prostheses; from grc, πρόσθεσις, prósthesis, addition, application, attachment), or a prosthetic implant, is an artificial device that replaces a missing body part, which may be lost through trau ...

foot. The painkillers

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It i ...

he was taking were interfering with his thinking, so he decided to stop taking them, instead using his willpower to deal with the pain, including use of the placebo effect

A placebo ( ) is a substance or treatment which is designed to have no therapeutic value. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like Saline (medicine), saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

In general ...

where he would convince himself that he had taken painkillers while drinking only water. Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent serie ...

said that it was the hardiness of Teller's spirit, rather than stoicism, that allowed him to cope so well with the accident.

In 1929, Teller transferred to the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

where in 1930, he received his PhD in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

under Heisenberg. Teller's dissertation dealt with one of the first accurate quantum mechanical

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, qua ...

treatments of the hydrogen molecular ion

The dihydrogen cation or hydrogen molecular ion is a cation (positive ion) with formula . It consists of two hydrogen nuclei (protons) sharing a single electron. It is the simplest molecular ion.

The ion can be formed from the ionization of a n ...

. That year, he befriended Russian physicists George Gamow

George Gamow (March 4, 1904 – August 19, 1968), born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov ( uk, Георгій Антонович Гамов, russian: Георгий Антонович Гамов), was a Russian-born Soviet and American polymath, theoret ...

and Lev Landau

Lev Davidovich Landau (russian: Лев Дави́дович Ланда́у; 22 January 1908 – 1 April 1968) was a Soviet-Azerbaijani physicist of Jewish descent who made fundamental contributions to many areas of theoretical physics.

His ac ...

. Teller's lifelong friendship with a Czech physicist, George Placzek

George Placzek (; September 26, 1905 – October 9, 1955) was a Moravian physicist.

Biography

Placzek was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Brünn, Moravia (now Brno, Czech Republic), the grandson of Chief Rabbi Baruch Placzek.PDF He studied ...

, was also very important for his scientific and philosophical development. It was Placzek who arranged a summer stay in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

with Enrico Fermi in 1932, thus orienting Teller's scientific career in nuclear physics. Also in 1930, Teller moved to the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

, then one of the world's great centers of physics due to the presence of Max Born and James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate i ...

, but after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Germany became unsafe for Jewish people, and he left through the aid of the International Rescue Committee. He went briefly to England, and moved for a year to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, where he worked under Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

. In February 1934 he married his long-time girlfriend Augusta Maria "Mici" (pronounced "Mitzi") Harkanyi, who was the sister of a friend. Since Mici was a Calvinist Christian, Edward and her were married in a Calvinist church. He returned to England in September 1934.

Mici had been a student in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, and wanted to return to the United States. Her chance came in 1935, when, thanks to George Gamow, Teller was invited to the United States to become a professor of physics at George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C. Chartered in 1821 by the United States Congress, GWU is the largest Higher educat ...

, where he worked with Gamow until 1941. At George Washington University in 1937, Teller predicted the Jahn–Teller effect

The Jahn–Teller effect (JT effect or JTE) is an important mechanism of spontaneous symmetry breaking in molecular and solid-state systems which has far-reaching consequences in different fields, and is responsible for a variety of phenomena in sp ...

, which distorts molecules in certain situations; this affects the chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the IUPAC nomenclature for organic transformations, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the pos ...

s of metals, and in particular the coloration of certain metallic dyes. Teller and Hermann Arthur Jahn

Hermann Arthur Jahn (born 31 May 1907, Colchester, England; d. 24 October 1979 Southampton) was a British scientist of German descent. With Edward Teller, he identified the Jahn–Teller effect.

Early life

He was the son of Friedrich Wilhelm Herm ...

analyzed it as a piece of purely mathematical physics. In collaboration with Stephen Brunauer and Paul Hugh Emmett

Paul Hugh Emmett (September 22, 1900 – April 22, 1985) was an American chemist best known for his pioneering work in the field of catalysis and for his work on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He spearheaded the research to separate is ...

, Teller also made an important contribution to surface physics and chemistry: the so-called Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) isotherm. Teller and Mici became naturalized citizens of the United States on March 6, 1941.

When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

began, Teller wanted to contribute to the war effort. On the advice of the well-known Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

aerodynamicist

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

and fellow Hungarian émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followin ...

Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

, Teller collaborated with his friend Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

in developing a theory of shock-wave propagation. In later years, their explanation of the behavior of the gas behind such a wave proved valuable to scientists who were studying missile re-entry.

Manhattan Project

Los Alamos Laboratory

In 1942, Teller was invited to be part ofRobert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

's summer planning seminar, at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

for the origins of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, the Allied effort to develop the first nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s. A few weeks earlier, Teller had been meeting with his friend and colleague Enrico Fermi about the prospects of atomic warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

, and Fermi had nonchalantly suggested that perhaps a weapon based on nuclear fission could be used to set off an even larger nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei are combined to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles ( neutrons or protons). The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manife ...

reaction. Even though he initially explained to Fermi why he thought the idea would not work, Teller was fascinated by the possibility and was quickly bored with the idea of "just" an atomic bomb even though this was not yet anywhere near completion. At the Berkeley session, Teller diverted discussion from the fission weapon to the possibility of a fusion weapon—what he called the "Super", an early concept of what was later to be known as a hydrogen bomb.

Arthur Compton, the chairman of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

physics department, coordinated the uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

research of Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, the University of Chicago, and the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

. To remove disagreement and duplication, Compton transferred the scientists to the Metallurgical Laboratory at Chicago. Teller was left behind at first, because while he and Mici were now American citizens, they still had relatives in enemy countries. In early 1943, the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

was established in Los Alamos, New Mexico

Los Alamos is an census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, that is recognized as the development and creation place of the atomic bomb—the primary objective of the Manhattan Project by Los Alamos National Labo ...

to design an atomic bomb, with Oppenheimer as its director. Teller moved there in March 1943. Apparently, Teller managed to annoy his neighbors there by playing the piano late in the night.

Teller became part of the Theoretical (T) Division. He was given a secret identity of Ed Tilden. He was irked at being passed over as its head; the job was instead given to Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

. Oppenheimer had him investigate unusual approaches to building fission weapons, such as autocatalysis

A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.Steinfeld J.I., Francisco J.S. and Hase W.L. ''Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 199 ...

, in which the efficiency of the bomb would increase as the nuclear chain reaction progressed, but proved to be impractical. He also investigated using uranium hydride

Uranium hydride, also called uranium trihydride (UH3), is an inorganic compound and a hydride of uranium.

Properties

Uranium hydride is a highly toxic, brownish grey to brownish black pyrophoric powder or brittle solid. Its density at 20 ° ...

instead of uranium metal, but its efficiency turned out to be "negligible or less". He continued to push his ideas for a fusion weapon even though it had been put on a low priority during the war (as the creation of a fission weapon proved to be difficult enough). On a visit to New York, he asked Maria Goeppert-Mayer

Maria Goeppert Mayer (; June 28, 1906 – February 20, 1972) was a German-born American theoretical physicist, and Nobel laureate in Physics for proposing the nuclear shell model of the atomic nucleus. She was the second woman to win a Nobel Pri ...

to carry out calculations on the Super for him. She confirmed Teller's own results: the Super was not going to work.

A special group was established under Teller in March 1944 to investigate the mathematics of an implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

. It too ran into difficulties. Because of his interest in the Super, Teller did not work as hard on the implosion calculations as Bethe wanted. These too were originally low-priority tasks, but the discovery of spontaneous fission in plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

by Emilio Segrè

Emilio Gino Segrè (1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian-American physicist and Nobel laureate, who discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was awarded the Nobe ...

's group gave the implosion bomb increased importance. In June 1944, at Bethe's request, Oppenheimer moved Teller out of T Division, and placed him in charge of a special group responsible for the Super, reporting directly to Oppenheimer. He was replaced by Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

from the British Mission, who in turn brought in Klaus Fuchs, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

. Teller's Super group became part of Fermi's F Division when he joined the Los Alamos Laboratory in September 1944. It included Stanislaw Ulam, Jane Roberg, Geoffrey Chew, Harold and Mary Argo, and Maria Goeppert-Mayer

Maria Goeppert Mayer (; June 28, 1906 – February 20, 1972) was a German-born American theoretical physicist, and Nobel laureate in Physics for proposing the nuclear shell model of the atomic nucleus. She was the second woman to win a Nobel Pri ...

.

Teller made valuable contributions to bomb research, especially in the elucidation of the implosion mechanism. He was the first to propose the solid pit design that was eventually successful. This design became known as a " Christy pit", after the physicist Robert F. Christy who made the pit a reality. Teller was one of the few scientists to actually watch (with eye protection) the Trinity nuclear test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

in July 1945, rather than follow orders to lie on the ground with backs turned. He later said that the atomic flash "was as if I had pulled open the curtain in a dark room and broad daylight streamed in".

Decision to drop the bombs

In the days before and after the first demonstration of a nuclear weapon, theTrinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

in July 1945, his fellow Hungarian Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

circulated the Szilard petition, which argued that a demonstration to the Japanese of the new weapon should occur prior to actual use on Japan, and with that hopefully the weapons would never be used on people. In response to Szilard's petition, Teller consulted his friend Robert Oppenheimer. Teller believed that Oppenheimer was a natural leader and could help him with such a formidable political problem. Oppenheimer reassured Teller that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Bolstered by Oppenheimer's influence, he decided to not sign the petition.

Teller therefore penned a letter in response to Szilard that read:

On reflection on this letter years later when he was writing his memoirs, Teller wrote:

Unknown to Teller at the time, four of his colleagues were solicited by the then secret May to June 1945 Interim Committee. It is this organization which ultimately decided on how the new weapons should initially be used. The committee's four-member ''Scientific Panel'' was led by Oppenheimer, and concluded immediate military use on Japan was the best option:

Teller later learned of Oppenheimer's solicitation and his role in the Interim Committee's decision to drop the bombs, having secretly endorsed an immediate military use of the new weapons. This was contrary to the impression that Teller had received when he had personally asked Oppenheimer about the Szilard petition: that the nation's fate should be left to the sensible politicians in Washington. Following Teller's discovery of this, his relationship with his advisor began to deteriorate.

In 1990, the historian Barton Bernstein argued that it is an "unconvincing claim" by Teller that he was a "covert dissenter" to the use of the bomb. In his 2001 ''Memoirs'', Teller claims that he did lobby Oppenheimer, but that Oppenheimer had convinced him that he should take no action and that the scientists should leave military questions in the hands of the military; Teller claims he was not aware that Oppenheimer and other scientists were being consulted as to the actual use of the weapon and implies that Oppenheimer was being hypocritical.

Hydrogen bomb

Despite an offer fromNorris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbur ...

, who had replaced Oppenheimer as the director of Los Alamos in November 1945, to become the head of the Theoretical (T) Division, Teller left Los Alamos on February 1, 1946, to return to the University of Chicago as a professor and close associate of Fermi and Goeppert-Mayer. Mayer's work on the internal structure of the elements would earn her the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963.

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as

On April 18–20, 1946, Teller participated in a conference at Los Alamos to review the wartime work on the Super. The properties of thermonuclear fuels such as deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of a deuterium atom, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one ...

and the possible design of a hydrogen bomb were discussed. It was concluded that Teller's assessment of a hydrogen bomb had been too favourable, and that both the quantity of deuterium needed, as well as the radiation losses during deuterium burning

Deuterium fusion, also called deuterium burning, is a nuclear fusion reaction that occurs in stars and some substellar objects, in which a deuterium nucleus and a proton combine to form a helium-3 nucleus. It occurs as the second stage of the p ...

, would shed doubt on its workability. Addition of expensive tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

to the thermonuclear mixture would likely lower its ignition temperature, but even so, nobody knew at that time how much tritium would be needed, and whether even tritium addition would encourage heat propagation.

At the end of the conference, in spite of opposition by some members such as Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

, Teller submitted an optimistic report in which he said that a hydrogen bomb was feasible, and that further work should be encouraged on its development. Fuchs also participated in this conference, and transmitted this information to Moscow. With John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

, he contributed an idea of using implosion to ignite the Super. The model of Teller's "classical Super" was so uncertain that Oppenheimer would later say that he wished the Russians were building their own hydrogen bomb based on that design, so that it would almost certainly retard their progress on it.

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

, forming such puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

s as the Hungarian People's Republic

The Hungarian People's Republic ( hu, Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist state from 20 August 1949

to 23 October 1989.

It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet U ...

in Teller's homeland of Hungary, where much of his family still lived, on August 20, 1949. Following the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

's first test detonation of an atomic bomb on August 29, 1949, President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

announced a crash development program for a hydrogen bomb.

Teller returned to Los Alamos in 1950 to work on the project. He insisted on involving more theorists, but many of Teller's prominent colleagues, like Fermi and Oppenheimer, were sure that the project of the H-bomb was technically infeasible and politically undesirable. None of the available designs were yet workable. However Soviet scientists who had worked on their own hydrogen bomb have claimed that they developed it independently.

In 1950, calculations by the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam and his collaborator Cornelius Everett, along with confirmations by Fermi, had shown that not only was Teller's earlier estimate of the quantity of tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

needed for the H-bomb a low one, but that even with higher amounts of tritium, the energy loss in the fusion process would be too great to enable the fusion reaction to propagate. However, in 1951 Teller and Ulam made a breakthrough, and invented a new design, proposed in a classified March 1951 paper, ''On Heterocatalytic Detonations I: Hydrodynamic Lenses and Radiation Mirrors'', for a practical megaton-range H-bomb. The exact contribution provided respectively from Ulam and Teller to what became known as the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

is not definitively known in the public domain, and the exact contributions of each and how the final idea was arrived upon has been a point of dispute in both public and classified discussions since the early 1950s.

In an interview with ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it ...

'' from 1999, Teller told the reporter:

The issue is controversial. Bethe considered Teller's contribution to the invention of the H-bomb a true innovation as early as 1952, and referred to his work as a "stroke of genius" in 1954. In both cases, however, Bethe emphasized Teller's role as a way of stressing that the development of the H-bomb could not have been hastened by additional support or funding, and Teller greatly disagreed with Bethe's assessment. Other scientists (antagonistic to Teller, such as J. Carson Mark) have claimed that Teller would have never gotten any closer without the assistance of Ulam and others. Ulam himself claimed that Teller only produced a "more generalized" version of Ulam's original design.

The breakthrough—the details of which are still classified—was apparently the separation of the fission and fusion components of the weapons, and to use the X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s produced by the fission bomb to first compress the fusion fuel (by process known as "radiation implosion") before igniting it. Ulam's idea seems to have been to use mechanical shock from the primary to encourage fusion in the secondary, while Teller quickly realized that X-rays from the primary would do the job much more symmetrically. Some members of the laboratory (J. Carson Mark in particular) later expressed the opinion that the idea to use the X-rays would have eventually occurred to anyone working on the physical processes involved, and that the obvious reason why Teller thought of it right away was because he was already working on the " Greenhouse" tests for the spring of 1951, in which the effect of X-rays from a fission bomb on a mixture of deuterium and tritium was going to be investigated.

Whatever the actual components of the so-called Teller–Ulam design and the respective contributions of those who worked on it, after it was proposed it was immediately seen by the scientists working on the project as the answer which had been so long sought. Those who previously had doubted whether a fission-fusion bomb would be feasible at all were converted into believing that it was only a matter of time before both the US and the USSR had developed multi-megaton weapons. Even Oppenheimer, who was originally opposed to the project, called the idea "technically sweet".

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the

Though he had helped to come up with the design and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Teller was not chosen to head the development project (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this). In 1952 he left Los Alamos and joined the newly established Livermore branch of the University of California Radiation Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

, which had been created largely through his urging. After the detonation of Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab ...

, the first thermonuclear weapon to utilize the Teller–Ulam configuration, on November 1, 1952, Teller became known in the press as the "father of the hydrogen bomb". Teller himself refrained from attending the test—he claimed not to feel welcome at the Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name given by the United States government to a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean at which it conducted nuclear testing between 1946 and 1962. The U.S. tested a ...

—and instead saw its results on a seismograph in the basement of a hall in Berkeley.

There was an opinion that by analyzing the fallout from this test, the Soviets (led in their H-bomb work by Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

) could have deciphered the new American design. However, this was later denied by the Soviet bomb researchers. Because of official secrecy, little information about the bomb's development was released by the government, and press reports often attributed the entire weapon's design and development to Teller and his new Livermore Laboratory (when it was actually developed by Los Alamos).

Many of Teller's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a part in, and in response, with encouragement from Enrico Fermi, Teller authored an article titled "The Work of Many People", which appeared in ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

'' magazine in February 1955, emphasizing that he was not alone in the weapon's development. He would later write in his memoirs that he had told a "white lie" in the 1955 article in order to "soothe ruffled feelings", and claimed full credit for the invention.

Teller was known for getting engrossed in projects which were theoretically interesting but practically unfeasible (the classic "Super" was one such project.) About his work on the hydrogen bomb, Bethe said:

During the Manhattan Project, Teller advocated the development of a bomb using uranium hydride, which many of his fellow theorists said would be unlikely to work. At Livermore, Teller continued work on the hydride bomb, and the result was a dud. Ulam once wrote to a colleague about an idea he had shared with Teller: "Edward is full of enthusiasm about these possibilities; this is perhaps an indication they will not work." Fermi once said that Teller was the only monomania

In 19th-century psychiatry, monomania (from Greek , one, and , meaning "madness" or "frenzy") was a form of partial insanity conceived as single psychological obsession in an otherwise sound mind.

Types

Monomania may refer to:

* De Clerambaul ...

c he knew who had several manias.

Carey Sublette of Nuclear Weapon Archive argues that Ulam came up with the radiation implosion compression design of thermonuclear weapons, but that on the other hand Teller has gotten little credit for being the first to propose fusion boosting

A boosted fission weapon usually refers to a type of nuclear bomb that uses a small amount of fusion fuel to increase the rate, and thus yield, of a fission reaction. The neutrons released by the fusion reactions add to the neutrons released d ...

in 1945, which is essential for miniaturization and reliability and is used in all of today's nuclear weapons.

Oppenheimer controversy

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney

Teller became controversial in 1954 when he testified against Oppenheimer at Oppenheimer's security clearance hearing. Teller had clashed with Oppenheimer many times at Los Alamos over issues relating both to fission and fusion research, and during Oppenheimer's trial he was the only member of the scientific community to state that Oppenheimer should not be granted security clearance.

Asked at the hearing by Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) attorney Roger Robb

Roger Robb (July 7, 1907 – December 19, 1985) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and trial attorney, best known for his key role as special counsel to an Atomic Energy Co ...

whether he was planning "to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States", Teller replied that:I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and a very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite.He was immediately asked whether he believed that Oppenheimer was a "security risk", to which he testified: Teller also testified that Oppenheimer's opinion about the thermonuclear program seemed to be based more on the scientific feasibility of the weapon than anything else. He additionally testified that Oppenheimer's direction of Los Alamos was "a very outstanding achievement" both as a scientist and an administrator, lauding his "very quick mind" and that he made "just a most wonderful and excellent director". After this, however, he detailed ways in which he felt that Oppenheimer had hindered his efforts towards an active thermonuclear development program, and at length criticized Oppenheimer's decisions not to invest more work onto the question at different points in his career, saying: "If it is a question of wisdom and judgment, as demonstrated by actions since 1945, then I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance." By recasting a difference of judgment over the merits of the early work on the hydrogen bomb project into a matter of a security risk, Teller effectively damned Oppenheimer in a field where security was necessarily of paramount concern. Teller's testimony thereby rendered Oppenheimer vulnerable to charges by a Congressional aide that he was a Soviet spy, which resulted in the destruction of Oppenheimer's career. Oppenheimer's security clearance was revoked after the hearings. Most of Teller's former colleagues disapproved of his testimony and he was ostracized by much of the scientific community. After the fact, Teller consistently denied that he was intending to damn Oppenheimer, and even claimed that he was attempting to exonerate him. However, documentary evidence has suggested that this was likely not the case. Six days before the testimony, Teller met with an AEC liaison officer and suggested "deepening the charges" in his testimony. Teller always insisted that his testimony had not significantly harmed Oppenheimer. In 2002, Teller contended that Oppenheimer was "not destroyed" by the security hearing but "no longer asked to assist in policy matters". He claimed his words were an overreaction, because he had only just learned of Oppenheimer's failure to immediately report an approach by

Haakon Chevalier

Haakon Maurice Chevalier (Lakewood Township, New Jersey, September 10, 1901 – July 4, 1985) was an American writer, translator, and professor of French literature at the University of California, Berkeley best known for his friendship with p ...

, who had approached Oppenheimer to help the Russians. Teller said that, in hindsight, he would have responded differently.

Historian Richard Rhodes

Richard Lee Rhodes (born July 4, 1937) is an American historian, journalist, and author of both fiction and non-fiction, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning ''The Making of the Atomic Bomb'' (1986), and most recently, ''Energy: A Human Histor ...

said that in his opinion it was already a foregone conclusion that Oppenheimer would have his security clearance revoked by then AEC chairman Lewis Strauss

Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss ( "straws"; January 31, 1896January 21, 1974) was an American businessman, philanthropist, and naval officer who served two terms on the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the second as its chairman. He was a major ...

, regardless of Teller's testimony. However, as Teller's testimony was the most damning, he was singled out and blamed for the hearing's ruling, losing friends due to it, such as Robert Christy

Robert Frederick Christy (May 14, 1916 – October 3, 2012) was a Canadian-American theoretical physicist and later astrophysicist who was one of the last surviving people to have worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. He briefly ...

, who refused to shake his hand in one infamous incident. This was emblematic of his later treatment which resulted in him being forced into the role of an outcast of the physics community, thus leaving him little choice but to align himself with industrialists.

US government work and political advocacy

After the Oppenheimer controversy, Teller became ostracized by much of the scientific community, but was still quite welcome in the government and military science circles. Along with his traditional advocacy for nuclear energy development, a strong nuclear arsenal, and a vigorous nuclear testing program, he had helped to developnuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

safety standards as the chair of the Reactor Safeguard Committee of the AEC in the late 1940s, and in the late 1950s headed an effort at General Atomics

General Atomics is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, specializing in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion energy. Th ...

which designed research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or marit ...

s in which a nuclear meltdown

A nuclear meltdown (core meltdown, core melt accident, meltdown or partial core melt) is a severe nuclear reactor accident that results in core damage from overheating. The term ''nuclear meltdown'' is not officially defined by the Internatio ...

would be impossible. The TRIGA

TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomics) is a class of nuclear research reactor designed and manufactured by General Atomics. The design team for TRIGA, which included Edward Teller, was led by the physicist Freeman Dyson.

Design

...

(''Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomic'') has been built and used in hundreds of hospitals and universities worldwide for medical isotope production and research.

Teller promoted increased defense spending to counter the perceived Soviet missile threat. He was a signatory to the 1958 report by the military sub-panel of the Rockefeller Brothers funded Special Studies Project, which called for a $3 billion annual increase in America's military budget.

In 1956 he attended the Project Nobska

Project Nobska was a 1956 summer study on anti-submarine warfare (ASW) for the United States Navy ordered by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke. It is also referred to as the Nobska Study, named for its location on Nobska Point nea ...

anti-submarine warfare

Anti-submarine warfare (ASW, or in older form A/S) is a branch of underwater warfare that uses surface warships, aircraft, submarines, or other platforms, to find, track, and deter, damage, or destroy enemy submarines. Such operations are t ...

conference, where discussion ranged from oceanography to nuclear weapons. In the course of discussing a small nuclear warhead for the Mark 45 torpedo

The Mark 45 anti-submarine torpedo, a.k.a. ASTOR, was a submarine-launched wire-guided nuclear torpedo designed by the United States Navy for use against high-speed, deep-diving, enemy submarines. This was one of several weapons recommended for ...

, he started a discussion on the possibility of developing a physically small one-megaton nuclear warhead for the Polaris missile

The UGM-27 Polaris missile was a two-stage solid-fueled nuclear-armed submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). As the United States Navy's first SLBM, it served from 1961 to 1980.

In the mid-1950s the Navy was involved in the Jupiter missi ...

. His counterpart in the discussion, J. Carson Mark from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, at first insisted it could not be done. However, Dr. Mark eventually stated that a half-megaton warhead of small enough size could be developed. This yield, roughly thirty times that of the Hiroshima bomb, was enough for Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenn ...

, who was present in person, and Navy strategic missile development shifted from Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

to Polaris by the end of the year.

He was Director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which he helped to found with Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation f ...

, from 1958 to 1960, and after that he continued as an Associate Director. He chaired the committee that founded the Space Sciences Laboratory

The Space Sciences Laboratory (SSL) is an Organized Research Unit (ORU) of the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1959, the laboratory is located in the Berkeley Hills above the university campus. It has developed and continues t ...

at Berkeley. He also served concurrently as a Professor of Physics at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

. He was a tireless advocate of a strong nuclear program and argued for continued testing and development—in fact, he stepped down from the directorship of Livermore so that he could better lobby

Lobby may refer to:

* Lobby (room), an entranceway or foyer in a building

* Lobbying, the action or the group used to influence a viewpoint to politicians

:* Lobbying in the United States, specific to the United States

* Lobby (food), a thick stew ...

against the proposed test ban. He testified against the test ban both before Congress as well as on television.

Teller established the Department of Applied Science at the University of California, Davis

The University of California, Davis (UC Davis, UCD, or Davis) is a public land-grant research university near Davis, California. Named a Public Ivy, it is the northernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California system. The inst ...

and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 1963, which holds the Edward Teller endowed professorship in his honor. In 1975 he retired from both the lab and Berkeley, and was named Director Emeritus of the Livermore Laboratory and appointed Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, an ...

. After the end of communism in Hungary

Communism, Communist rule in the People's Republic of Hungary came to an end in 1989 by a peaceful transition of power, peaceful transition to a democratic system. After the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was suppressed by Soviet forces, Hungary ...

in 1989, he made several visits to his country of origin, and paid careful attention to the political changes there.

Global climate change

Teller was one of the first prominent people to raise the danger ofclimate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, driven by the burning of fossil fuels. At an address to the membership of the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

in December 1957, Teller warned that the large amount of carbon-based fuel that had been burnt since the mid-19th century was increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

in the atmosphere, which would "act in the same way as a greenhouse and will raise the temperature at the surface", and that he had calculated that if the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased by 10% "an appreciable part of the polar ice might melt".

In 1959, at a symposium organised by the American Petroleum Institute

The American Petroleum Institute (API) is the largest U.S. trade association for the oil and natural gas industry. It claims to represent nearly 600 corporations involved in production, refinement, distribution, and many other aspects of the ...

and the Columbia Graduate School of Business

Columbia Business School (CBS) is the business school of Columbia University, a private research university in New York City. Established in 1916, Columbia Business School is one of six Ivy League business schools and is one of the oldest busi ...

for the centennial of the American oil industry, Edward Teller warned that:

Non-military uses of nuclear explosions

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under

Teller was one of the strongest and best-known advocates for investigating non-military uses of nuclear explosives, which the United States explored under Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

. One of the most controversial projects he proposed was a plan to use a multi-megaton hydrogen bomb to dig a deep-water harbor more than a mile long and half a mile wide to use for shipment of resources from coal and oil fields through Point Hope, Alaska

Point Hope ( ik, Tikiġaq, ) is a city in North Slope Borough, Alaska, United States. At the 2010 census the population was 674, down from 757 in 2000. In the 2020 Census, population rose to 830.

Like many isolated communities in Alaska, the ...

. The Atomic Energy Commission accepted Teller's proposal in 1958 and it was designated Project Chariot

Project Chariot was a 1958 US Atomic Energy Commission proposal to construct an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson on the North Slope of the U.S. state of Alaska by burying and detonating a string of nuclear devices.

History

The project o ...

. While the AEC was scouting out the Alaskan site, and having withdrawn the land from the public domain, Teller publicly advocated the economic benefits of the plan, but was unable to convince local government leaders that the plan was financially viable.

Other scientists criticized the project as being potentially unsafe for the local wildlife and the Inupiat people living near the designated area, who were not officially told of the plan until March 1960. Additionally, it turned out that the harbor would be ice-bound for nine months out of the year. In the end, due to the financial infeasibility of the project and the concerns over radiation-related health issues, the project was abandoned in 1962.

A related experiment which also had Teller's endorsement was a plan to extract oil from the tar sands

Oil sands, tar sands, crude bitumen, or bituminous sands, are a type of unconventional petroleum deposit. Oil sands are either loose sands or partially consolidated sandstone containing a naturally occurring mixture of sand, clay, and wate ...

in northern Alberta