Ernest Poole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Cook Poole (January 23, 1880 – January 10, 1950) was an American

Poole graduated from Princeton ''

Poole graduated from Princeton ''

journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

, novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to ...

, and playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

. Poole is best remembered for his sympathetic first-hand reportage of revolutionary Russia during and immediately after the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

and Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and as a popular writer of proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...

-tinged fiction during the era of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the 1920s.

Poole was the winner of the first Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

, awarded in 1918 for his book, ''His Family

''His Family'' is a novel by Ernest Poole published in 1917 about the life of a New York widower and his three daughters in the 1910s. It received the first Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1918.

Plot introduction

''His Family'' tells the story of ...

.''

Biography

Early years

Ernest Cook Poole was born inChicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, on January 23, 1880, to Abram Poole and Mary Howe Poole.Edd Applegate, ''Muckrackers: A Biographical Dictionary of Writers and Editors.'' Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2008; pg. 142. His Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

-born father was a successful commodities trader at the Chicago Board of Trade

The Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), established on April 3, 1848, is one of the world's oldest futures and options exchanges. On July 12, 2007, the CBOT merged with the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) to form CME Group. CBOT and three other excha ...

, his mother hailed from a well-established Chicago family; together they raised 7 children.

Poole was educated at home until he was almost 7 years old, at which time he was enrolled in Chicago's University School for Boys. There he first showed a proclivity for the written word, working briefly on the staff of the school newspaper. His was a privileged youth, spending summers at the family's seasonal home at Lake Forest, on the shores of Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

. The family's Michigan Avenue home in Chicago was populated with servants, including gardeners and governesses, and he grew up in proximity of the scions of the city elite, including young relatives of Cyrus McCormick

Cyrus Hall McCormick (February 15, 1809 – May 13, 1884) was an American inventor and businessman who founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which later became part of the International Harvester Company in 1902. Originally from the ...

and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

Following high school graduation, Poole, an accomplished violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

ist, took a year off to study music, with a view to becoming a professional composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

. He found the process of writing music difficult, however, and — inspired by his literary-oriented and story-telling father — turned his attention to the written word as a possible profession.

After his year-long escape from formal education, Poole moved to Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

to attend Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, where he attended courses in political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

taught by Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. There he continued to demonstrate an interest in journalism and fiction writing, working on the staff of the school's daily newspaper, ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( it, Il Principe ; la, De Principatibus) is a 16th-century political treatise written by Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli as an instruction guide for new princes and royals. The general theme of ''The ...

'' — before finding straight journalism tedious. He moved from nuts-and-bolts journalism to the arts, contributing material to the campus literary magazine, ''The Lit,'' and penning two libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

s for the illustrious Princeton Triangle Club, although both were rejected.Poole, ''The Bridge,'' pg. 65.

It was at Princeton that Poole was influenced to the ideas of progressive reform associated with the burgeoning muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

movement, with the book ''How The Other Half Lives

''How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York'' (1890) is an early publication of photojournalism by Jacob Riis, documenting squalid living conditions in New York City slums in the 1880s. The photographs served as a basis f ...

'' by Jacob Riis

Jacob August Riis ( ; May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish-American social reformer, "muckraking" journalist and social documentary photographer. He contributed significantly to the cause of urban reform in America at the turn of the twen ...

playing a particularly pivotal role in the evolution of Poole's worldview. He also read translations of Russian classics by Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

and Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

, which deeply impressed Poole for their realistic style and aroused what would become a lifelong interest in him in the authors' native land.

Settlement worker

Poole graduated from Princeton ''

Poole graduated from Princeton ''cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sou ...

'' in 1902 and immediately moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to live in the University Settlement House

The University Settlement Society of New York is an American organization which provides educational and social services to immigrants and low-income families, located at 184 Eldridge Street (corner of Eldridge and Rivington Streets) on the Lowe ...

on the city's impoverished Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally an im ...

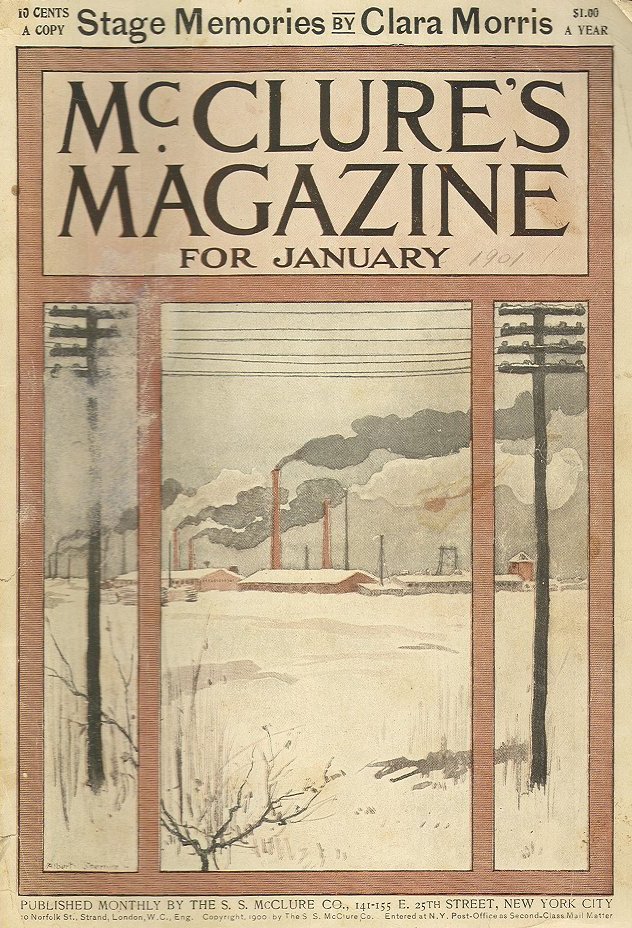

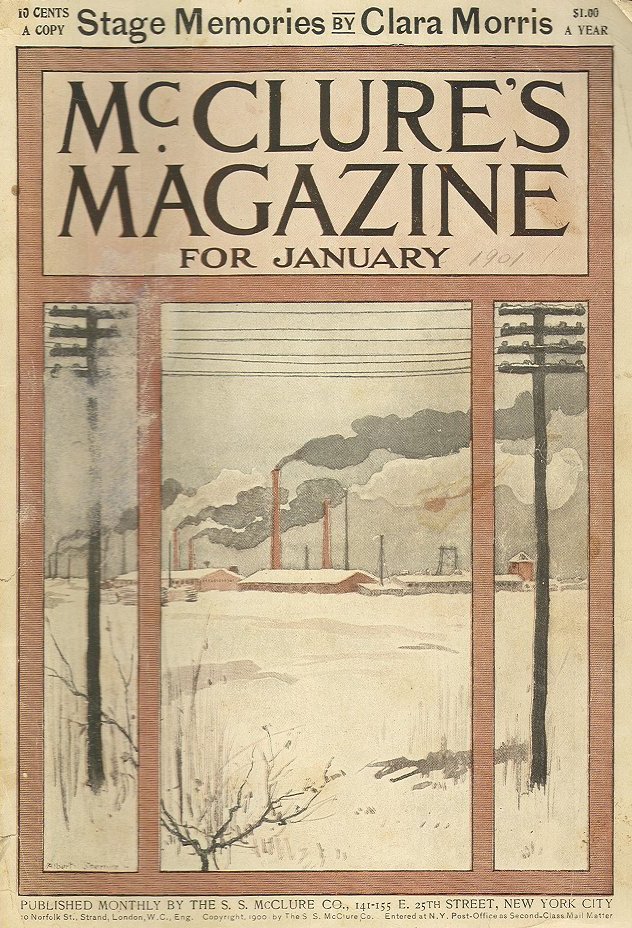

. During his stint as a settlement worker, Poole gained the notice of editors at ''McClure's Magazine

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wat ...

'' for an article he wrote on the social situation in New York's Chinatown district and authored a report for the New York Child Labor Committee on the continuing child labor

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

problem.

Pushed by the Child Labor Committee to seek publicity by rewriting some of his lurid anecdotes of the life of street urchins, Poole wrote an article that early in 1903 found its way into the fledgling muckraking magazine, ''McClure's.'' Payment for the freelance effort was received and confidence boosted. The next phase of Poole's life, that of a professional writer, had begun.

Headstrong and confident, Poole immersed himself in his passion, fiction, while still ensconced as a settlement worker. Three short stories were immediately penned and sent out to various New York magazines — only to be returned with letters of rejection.Poole, ''The Bridge,'' pg. 70. Poole retreated to writing short works of investigative journalism on the boys of the city streets and met with better success, seeing print for one piece in ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Collie ...

'' and two others in the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

.''

Poole's settlement house was active teaching classes and housing club groups during the day.Poole, ''The Bridge,'' pg. 72. In the evenings it hosted a steady stream of guests, including some of the most famous progressive activists of the day, including social worker Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

, journalist Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in ''McClure's'', called "Twe ...

, British author H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Poole's time as a settlement worker at an end, he threw himself into investigative journalism. In 1904 the popular illustrated news weekly '' The Outlook'' dispatched Poole to live for six weeks in the packinghouse district of Chicago to report on the ongoing stockyards' strike, which prominently featured a melange of striking new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe against thousands of African-American

Poole's time as a settlement worker at an end, he threw himself into investigative journalism. In 1904 the popular illustrated news weekly '' The Outlook'' dispatched Poole to live for six weeks in the packinghouse district of Chicago to report on the ongoing stockyards' strike, which prominently featured a melange of striking new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe against thousands of African-American

Poole was slow to join the growing

Poole was slow to join the growing

"Book World: Reissue of Ernest Poole’s ‘The Harbor’ long overdue"

''The Washington Post'', Jan. 13, 2012. Poole's next novel attempted to follow up the successful ''His Family'' with a sequel, ''His Second Wife,'' published in serial form in ''McClure's'' before being released in hard covers later in 1918. This book proved distinctly less successful than his previous literary efforts with critics and the reading public, however, and Poole's fiction never achieved such acclaim again. From 1920 until 1934, Poole produced works of fiction for Macmillan at the rate of approximately one a year. While none of these attained the critical acclaim of Poole's wartime writings, the 1927 book ''Silent Storms'' was met with some degree of public success.

"Deaths: Ernest Poole, 69, War Reporter,"

''Brooklyn Daily Eagle,'' Jan. 11, 1950, pg. 15.

''The Voice of the Street.''

New York: A.S. Barnes, 1906.

''Katherine Breshkovsky: "For Russia's Freedom."''

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1906.

''The Harbor.''

New York: Macmillan, 1915.+ Audio version

* ''+ Audio version

''"The Dark People": Russia's Crisis.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''The Village: Russian Impressions.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''His Second Wife.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''Blind: A Story of These Times.''

New York: Macmillan, 1920.

''Beggar's Gold.''

New York: Macmillan, 1921.

''Millions.''

New York: Macmillan, 1922. * ''Danger.'' New York: Macmillan, 1923. * ''The Avalanche.'' New York: Macmillan, 1924. * ''The Little Dark Man and Other Russian Sketches.'' New York: Macmillan, 1925. —4 short stories. * ''The Hunter's Moon.'' New York: Macmillan, 1925. * ''With Eastern Eyes.'' New York: Macmillan, 1926. * ''Silent Storms.'' New York: Macmillan, 1927. * ''Car of Croesus.'' New York: Macmillan, 1930. * ''The Destroyer.'' New York: Macmillan, 1931. * ''Nurses on Horseback.'' New York: Macmillan, 1932. * ''Great Winds.'' New York: Macmillan, 1933. * ''One of Us.'' New York: Macmillan, 1934. * ''The Bridge: My Own Story.'' New York: Macmillan, 1940. —Memoir. * ''Giants Gone: Men Who Made Chicago.'' New York : Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill, 1943. * ''The Great White Hills of New Hampshire.'' Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1946. * ''Nancy Flyer: A Stagecoach Epic.'' New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1949.

"Abraham Cahan: Socialist — Journalist — Friend of the Ghetto,"

''The Outlook,'' Oct. 28, 1911. * "Our American Merchant Marine under Private Operation," ''The Saturday Evening Post'', vol. 202, no. 8 (Aug. 24, 1929) pp. 25, 142, 145-146, 149-150. * "Captain Dollar," (serialized in 5 parts) ''The Saturday Evening Post'', May 25-June 22, 1929. * "Frolicking and Vain Mirth," ''Woman's Day,'' April 1948.

In JSTOR

* Truman Frederick Keefer, ''Ernest Poole.'' New YorK: Twayne Publishers, 1966. * Truman Frederick Keefer, ''The Literary Career and Productions of Ernest Poole, American Novelist.'' PhD dissertation. Duke University, 1961. * Michaelyn Szlosek, ''Ernest Poole's The Harbor: A Study of a Problem Novel.'' PhD dissertation. Southern Connecticut State University, 1965.

Photos of the first edition of ''His Family,''

www.pprize.com/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Poole, Ernest 1880 births 1950 deaths Writers from Chicago Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners American male journalists 20th-century American novelists American male novelists Princeton University alumni 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American male writers Novelists from Illinois People from Sugar Hill, New Hampshire People from Franconia, New Hampshire Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

and Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, as well as renowned attorney Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

. Acquaintances were made and ideas absorbed by Poole, who increased in commitment to attempt to the wrongs of society through intelligent social reform.

Anxious to learn more about the people of the crowded Lower East Side milieu in which he lived, Poole set about learning Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

, eavesdropping on conversations and jotting down fragments of the dialog he heard for future use in his imaginative writing. He met and made friends with Abraham Cahan

Abraham "Abe" Cahan (Yiddish: אַבֿרהם קאַהאַן; July 7, 1860 – August 31, 1951) was a Lithuanian-born Jewish American socialist newspaper editor, novelist, and politician. Cahan was one of the founders of ''The Forward'' (), a ...

, publisher of the Yiddish-language ''Jewish Daily Forward

''The Forward'' ( yi, פֿאָרווערטס, Forverts), formerly known as ''The Jewish Daily Forward'', is an American news media organization for a American Jews, Jewish American audience. Founded in 1897 as a Yiddish-language daily socialis ...

'' ''(Der Forverts)'' and gained an appreciation from the venerable revolutionary of the struggle being waged by oppressed Jews and others against the Tsarist autocracy in Russia.

The tipping point for the 23-year old Poole as a settlement worker came when he was selected to investigate the problem of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in New York City's Lower East Side tenement slums. Poole spent weeks going from room to room observing and surveying residents and taking testimony about the fate of previous inhabitants. His report, "The Plague in Its Stronghold," generated attention from the press and Poole conducted tours of reporters and photographers around the tenement blocks, with the coverage spurring hearings of the New York State Legislature

The New York State Legislature consists of the two houses that act as the state legislature of the U.S. state of New York: The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly. The Constitution of New York does not designate an official ...

in Albany. The task proved a strain on Poole's mental and physical well-being and he himself became feverish and was sent home to the family summer home in Lake Forest to recuperate.

Magazine correspondent

Poole's time as a settlement worker at an end, he threw himself into investigative journalism. In 1904 the popular illustrated news weekly '' The Outlook'' dispatched Poole to live for six weeks in the packinghouse district of Chicago to report on the ongoing stockyards' strike, which prominently featured a melange of striking new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe against thousands of African-American

Poole's time as a settlement worker at an end, he threw himself into investigative journalism. In 1904 the popular illustrated news weekly '' The Outlook'' dispatched Poole to live for six weeks in the packinghouse district of Chicago to report on the ongoing stockyards' strike, which prominently featured a melange of striking new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe against thousands of African-American strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the st ...

s brought for the purpose to the city.

When his ''Outlook'' piece was completed, Poole stayed on the scene as the volunteer press agent for the union of the striking slaughterhouse workers. The job put him in touch with the young Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, who was on the scene to do research for what he hoped would become the ''"Uncle Tom's Cabin'' of the Labor Movement," published in 1906 as ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers wer ...

.'' Poole's close friends in New York included two others who would travel to Imperial Russia as correspondents in 1905 — the socialists Arthur Bullard

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more wi ...

and William English Walling

William English Walling (1877–1936) (known as "English" to friends and family) was an American labor reformer and Socialist Republican born into a wealthy family in Louisville, Kentucky. He founded the National Women's Trade Union League in 1903. ...

.

Back in New York, Poole met the émigré Russian revolutionary Yekaterina Breshkovskaya, the so-called "Little Grandmother of the Revolution." Together with an interpreter and a stenographer, Poole sat for eight hours listening to Breshkovskaya's personal story and the history of the revolutionary movement fighting for the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

of Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

. Poole's interview would ultimately result in a pamphlet issued by the Chicago socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

publishing house Charles H. Kerr & Co., ''For Russia's Freedom.''

Fascinated by the tumultuous Russian political situation, Poole successfully convinced ''The Outlook'' to send him to Russia as the magazine's correspondent and a contract was drawn up. Poole sailed for England, then proceeded to France before traveling by train to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

and on to Russia, bringing with him communications and money entrusted to him in Paris for underground Russian constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

alists. Together with a translator, Poole traveled Russia extensively in the early days of the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, ultimately turning in 14 pieces to ''The Outlook'' detailing his experiences and observations.

After his return from Russia, Poole continued to produce feature short stories depicting urban working class life for the periodical press, all the while gathering anecdotes for future novels. Poole split his output between ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'' and ''Everybody's Magazine

''Everybody's Magazine'' was an American magazine published from 1899 to 1929. The magazine was headquartered in New York City.

History and profile

The magazine was founded by Philadelphia merchant John Wanamaker in 1899, though he had little role ...

,'' as a successful freelance writer.

Poole married the former Margaret Ann Witherbotham in 1907 and the couple established a household in the Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

section of New York City.Applegate, ''Muckrackers,'' pg. 144. The couple would raise three children.

For several years after his marriage, Poole found himself to writing of plays for the stage, an offshoot of the writing profession that pitted low probability of success against potentially immense financial rewards if a piece was successfully staged.Poole, ''The Bridge,'' pg. 192. His first effort, revolving around life in a steel mill, failed to find a producer but his second, a drama about the construction of a bridge in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, led to six weeks of rehearsals and a grand New York opening — followed by poor reviews and a quick close.

Poole would ultimately write 11 plays for the New York stage, two of these in conjunction with Harriet Ford

Harriet Ford (after marriage, Morgan; 1863 – December 12, 1949) was an American actress and playwright who flourished during the latter part of the 19th century. Her contemporaries included: Edith Ellis, Marion Fairfax, Eleanor Gates, Georgia ...

. A total of three of Poole's efforts would be staged, with the two successful dramas running for 6 weeks and 3 months, respectively. His urge to write for the stage whetted, Poole would return to more secure forms of writing.

Political activism

Poole was slow to join the growing

Poole was slow to join the growing Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

(SPA), initially resisting joining because, as he later recalled, he had "got free from one church and I didn't propose to get into this other and write propaganda all my life, instead of the truth as I saw it and felt it." Around 1908 he made the acquaintance of party leader Morris Hillquit

Morris Hillquit (August 1, 1869 – October 8, 1933) was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America and prominent labor lawyer in New York City's Lower East Side. Together with Eugene V. Debs and Congressman Victor L. Berger, Hillqui ...

, however, who became a "lovable friend" and persuaded the non-Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

Poole that his views fell within the "very broad and liberal" ideological umbrella of the Socialist Party. Poole joined a branch of Local New York and maintained his red card in the organization at least through the years of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

From 1908 Poole began writing for the ''New York Call

The ''New York Call'' was a socialist daily newspaper published in New York City from 1908 through 1923. The ''Call'' was the second of three English-language dailies affiliated with the Socialist Party of America, following the ''Chicago Daily S ...

,'' a socialist daily closely associated with the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

(SPA). Poole was also among those left wing intellectuals who helped to found the Intercollegiate Socialist Society

The Intercollegiate Socialist Society (ISS) was a socialist student organization active from 1905 to 1921. It attracted many prominent intellectuals and writers and acted as an unofficial student wing of the Socialist Party of America. The Society ...

(ISS), joining in the task with his friends Arthur Bullard and Charles Edward Russell

Charles Edward Russell (September 25, 1860 in Davenport, Iowa – April 23, 1941 in Washington, D.C.) was an American journalist, opinion columnist, newspaper editor, and political activist. The author of a number of books of biography and socia ...

.

Novelist

Leaving the world of the stage, Poole began to concentrate on full length fiction. In the spring of 1912 he began research on the waterfront environs ofBrooklyn Heights, New York

Brooklyn Heights is a residential neighborhood within the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Old Fulton Street near the Brooklyn Bridge on the north, Cadman Plaza West on the east, Atlantic Avenue on the south, an ...

, gathering observations and anecdotes that he would painstakingly work into shape for the first of his major novels, '' The Harbor,'' which was accepted by Macmillan

MacMillan, Macmillan, McMillen or McMillan may refer to:

People

* McMillan (surname)

* Clan MacMillan, a Highland Scottish clan

* Harold Macmillan, British statesman and politician

* James MacMillan, Scottish composer

* William Duncan MacMillan ...

in the spring of 1914. Physically and emotionally drained by the writing process, Poole spent two months in Europe before returning to the family's new home in the White Mountains of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

to begin work on his next book.

This idyllic interlude was shattered in the summer of 1914 when World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

erupted across Europe.Poole, ''The Bridge,'' pg. 216. The world situation so dramatically changed, Poole recovered the manuscript for his book from Macmillans and spent a month writing a completely new ending. Drawn to cover the conflict as a war correspondent as if a moth to a flame, Poole belatedly attempted to make use of his contacts with the publishers of various magazines, but found that all the positions for correspondents in France and England had been filled. He was ultimately able, however, to persuade ''The Saturday Evening Post'' to send him to the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

capital of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

to cover the war from the opposite camp, and early in November 1914 he sailed aboard a British ship for Europe.

In Germany, joining other western war correspondents such as Jack Reed he viewed German hospitals, troop trains, and saw the front from the German side. He would spend three months in Europe covering the conflict.

Finally published in 1915, Poole's ''The Harbor'' was well received by critics and the reading public and his place in the American literary scene was thereby firmly established. He followed the book up with a new novel in 1917 dealing with intergenerational conflict, ''His Family.'' This book was also warmly regarded, resulting in Poole being awarded the first Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

in 1918, an award which at least one 21st Century literary critic has argued was awarded to Poole as much for his previous effort, ''The Harbor."Dennis Drabelle"Book World: Reissue of Ernest Poole’s ‘The Harbor’ long overdue"

''The Washington Post'', Jan. 13, 2012. Poole's next novel attempted to follow up the successful ''His Family'' with a sequel, ''His Second Wife,'' published in serial form in ''McClure's'' before being released in hard covers later in 1918. This book proved distinctly less successful than his previous literary efforts with critics and the reading public, however, and Poole's fiction never achieved such acclaim again. From 1920 until 1934, Poole produced works of fiction for Macmillan at the rate of approximately one a year. While none of these attained the critical acclaim of Poole's wartime writings, the 1927 book ''Silent Storms'' was met with some degree of public success.

Interpreter of the Bolshevik Revolution

In 1917 ''The Saturday Evening Post'' dispatched Poole to Russia to report on theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, where he joined other sympathetic American commentators such as John "Jack" Reed and Louise Bryant

Louise Bryant (December 5, 1885 – January 6, 1936) was an American feminist, political activist, and journalist best known for her sympathetic coverage of Russia and the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution, Russian Revolution of Novembe ...

. His journalism on the rapidly changing world in Russia was closely read by a curious public, and the articles subsequently provided the raw material for two works of non-fiction, ''"The Dark People": Russia's Crisis'' and ''The Village: Russian Impressions,'' both of which were published in book form by Macmillan in 1918.

Later years

After the war, Poole, Paul Kennaday, andArthur Livingston

Arthur Livingston (September 30, 1883 in Northbridge, Massachusetts – 1944), was an American professor of Romance languages and literatures, translator, and publisher, who played a significant role in introducing a number of European writers to r ...

initiated an agency, the Foreign Press Service, that negotiated for foreign authors with English-language publishers.

After a six year hiatus with Macmillan, Poole published his memoirs, ''The Bridge: My Own Story,'' in 1940. He returned to writing books during the final decade of his life, publishing one work of non-fiction on famous figures in Chicago history and two lesser novels.

Death and legacy

Ernest Poole died ofpneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

in New York City on Tuesday, January 10, 1950, thirteen days away from his 70th birthday.''Brooklyn Daily Eagle,'' Jan. 11, 1950, pg. 15.

Footnotes

Works

Books and pamphlets

''The Voice of the Street.''

New York: A.S. Barnes, 1906.

''Katherine Breshkovsky: "For Russia's Freedom."''

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1906.

''The Harbor.''

New York: Macmillan, 1915.

* ''

His Family

''His Family'' is a novel by Ernest Poole published in 1917 about the life of a New York widower and his three daughters in the 1910s. It received the first Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1918.

Plot introduction

''His Family'' tells the story of ...

.'' New York: Macmillan, 1917. ''"The Dark People": Russia's Crisis.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''The Village: Russian Impressions.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''His Second Wife.''

New York: Macmillan, 1918.

''Blind: A Story of These Times.''

New York: Macmillan, 1920.

''Beggar's Gold.''

New York: Macmillan, 1921.

''Millions.''

New York: Macmillan, 1922. * ''Danger.'' New York: Macmillan, 1923. * ''The Avalanche.'' New York: Macmillan, 1924. * ''The Little Dark Man and Other Russian Sketches.'' New York: Macmillan, 1925. —4 short stories. * ''The Hunter's Moon.'' New York: Macmillan, 1925. * ''With Eastern Eyes.'' New York: Macmillan, 1926. * ''Silent Storms.'' New York: Macmillan, 1927. * ''Car of Croesus.'' New York: Macmillan, 1930. * ''The Destroyer.'' New York: Macmillan, 1931. * ''Nurses on Horseback.'' New York: Macmillan, 1932. * ''Great Winds.'' New York: Macmillan, 1933. * ''One of Us.'' New York: Macmillan, 1934. * ''The Bridge: My Own Story.'' New York: Macmillan, 1940. —Memoir. * ''Giants Gone: Men Who Made Chicago.'' New York : Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill, 1943. * ''The Great White Hills of New Hampshire.'' Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1946. * ''Nancy Flyer: A Stagecoach Epic.'' New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1949.

Articles

"Abraham Cahan: Socialist — Journalist — Friend of the Ghetto,"

''The Outlook,'' Oct. 28, 1911. * "Our American Merchant Marine under Private Operation," ''The Saturday Evening Post'', vol. 202, no. 8 (Aug. 24, 1929) pp. 25, 142, 145-146, 149-150. * "Captain Dollar," (serialized in 5 parts) ''The Saturday Evening Post'', May 25-June 22, 1929. * "Frolicking and Vain Mirth," ''Woman's Day,'' April 1948.

Further reading

* Patrick Chura, "Ernest Poole's ''The Harbor'' as a Source for O'Neill's ''The Hairy Ape,"'' ''Eugene O'Neill Review,'' vol. 33, no. 1 (2012), pp. 24–42In JSTOR

* Truman Frederick Keefer, ''Ernest Poole.'' New YorK: Twayne Publishers, 1966. * Truman Frederick Keefer, ''The Literary Career and Productions of Ernest Poole, American Novelist.'' PhD dissertation. Duke University, 1961. * Michaelyn Szlosek, ''Ernest Poole's The Harbor: A Study of a Problem Novel.'' PhD dissertation. Southern Connecticut State University, 1965.

External links

* * * * *Photos of the first edition of ''His Family,''

www.pprize.com/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Poole, Ernest 1880 births 1950 deaths Writers from Chicago Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners American male journalists 20th-century American novelists American male novelists Princeton University alumni 20th-century American journalists 20th-century American male writers Novelists from Illinois People from Sugar Hill, New Hampshire People from Franconia, New Hampshire Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters