Capture of Jerusalem (1218) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of

The Hungarian army landed on 9 October 1217 on

The Hungarian army landed on 9 October 1217 on

Map by the University of Wisconsin Cartography Laboratory, facing pg. 487 of Volume II of ''A History of the Crusades'' (Setton, editor) Simon III of Sarrebrück was chosen as temporary leader pending the arrival of the rest of the fleet. Within a few days, the remaining ships arrived, carrying John of Brienne, Leopold VI of Austria and masters

In September 1219, Francis of Assisi arrived in the Crusader camp seeking permission from Pelagius to visit sultan al-Kamil. Francis had a long history with the Crusades. In 1205, Francis prepared to enlist in the army of

In September 1219, Francis of Assisi arrived in the Crusader camp seeking permission from Pelagius to visit sultan al-Kamil. Francis had a long history with the Crusades. In 1205, Francis prepared to enlist in the army of

Histoire des Sultans Mamlouks de l'Égypte

Paris. *''History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria,'' begun in the 10th century, and continued into the 13th century. Many of these primary sources can be found in Crusade Texts in Translation. Fifteenth century Italian chronicler Francesco Amadi wrote his ''Chroniques d'Amadi'' that includes the Fifth Crusade based on the original sources. German historian Reinhold Röhricht also compiled two collections of works concerning the Fifth Crusade: ''Scriptores Minores Quinti Belli sacri'' (1879)' and its continuation ''Testimonia minora de quinto bello sacro'' (1882). He also collaborated on the work ''Annales de Terre Sainte'' that provides a chronology of the Crusade correlated with the original sources. The reference to the Fifth Crusade is relatively new. Thomas FullerStephen, Leslie (1889). "wikisource:Fuller, Thomas (1608-1661) (DNB00), Thomas Fuller". In ''Dictionary of National Biography''. 20. London. pp. 315–320. called it simply Voyage 8 in his ''The Historie of the Holy Warre''. Joseph François Michaud, Joseph-François Michaud referred to it as part of the Sixth Crusade in his ''Histoire des Croisades'' (translation by British author William Robson (writer), William Robson), as did Joseph Toussaint Reinaud in his ''Histoire de la sixième croisade et de la prise de Damiette.'' Historian George William Cox, George Cox in his ''The'' ''Crusades'' regarded the Fifth and Sixth Crusades as a single campaign, but by the late 19th century, the designation of the Fifth Crusade was standard. The secondary sources are well-represented in the Bibliography, below. Tertiary sources include works by Louis Bréhier in the Catholic Encyclopedia, Ernest Barker in the Encyclopædia Britannica,Barker, Ernest (1911). "wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Crusades, Crusades". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 7 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–552. and Philip Schaff in the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopaedia of Religious Knowledge. Other works include The Mohammedan Dynasties by Stanley Lane-Poole and Bréhier's ''Crusades (Bibliography and Sources)'',Bréhier, Louis René (1908). "wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Crusades (Bibliography and Sources), Crusades (Sources and Bibliography)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. a concise summary of the historiography of the Crusades.

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al-Adil, brother of Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

.

After the failure of the Fourth Crusade, Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

again called for a crusade, and began organizing Crusading armies led by Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II ( hu, II. András, hr, Andrija II., sk, Ondrej II., uk, Андрій II; 117721 September 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1205 and 1235. He ruled the Principality of Halych from 11 ...

and Leopold VI of Austria

Leopold VI (15 October 1176 – 28 July 1230), known as Leopold the Glorious, was Duke of Styria from 1194 and Duke of Austria from 1198 to his death in 1230. He was a member of the House of Babenberg.

Biography

Leopold VI was the younger son ...

, soon to be joined by John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Champag ...

. An initial campaign in late 1217 in Syria was inconclusive, and Andrew departed. A German army led by cleric Oliver of Paderborn Oliver of Paderborn, also known as Thomas Olivier, Oliver the Saxon or Oliver of Cologne ( 1170 – 11 September 1227), was a Germans, German cleric, crusader and chronicler. He was the bishop of Paderborn from 1223 until 1225, when Pope Honorius II ...

, and a mixed army of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

and Frisian soldiers led by William I of Holland

William I (c. 1167 – 4 February 1222) was count of Holland from 1203 to 1222. He was the younger son of Floris III and Ada of Huntingdon.

Early life

William was born in The Hague, but raised in Scotland. He participated in the Third Cru ...

, then joined the Crusade in Acre, with a goal of first conquering Egypt, viewed as the key to Jerusalem. There, cardinal Pelagius Galvani arrived as papal legate and ''de facto'' leader of the Crusade, supported by John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Champag ...

and the masters of the Templars

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

, Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

and Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, who had taken the cross in 1215, did not participate as promised.

Following the successful siege of Damietta in 1218–1219, the Crusaders occupied the port for two years. Al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cr ...

, now sultan of Egypt, offered attractive peace terms, including the restoration of Jerusalem to Christian rule. The sultan was rebuked by Pelagius several times, and the Crusaders marched south towards Cairo in July 1221. En route, they attacked a stronghold of al-Kamil at the battle of Mansurah, but they were defeated, forced to surrender. The terms of surrender included the retreat from Damietta—leaving Egypt altogether—and an eight-year truce. The Fifth Crusade ended in September 1221, a Crusader defeat that accomplished nothing.

Background

By 1212,Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

had been pope for 14 years and had faced the disappointment of the Fourth Crusade and its inability to recover Jerusalem, the on-going Albigensian Crusade, begun in 1209, and the popular fervor of the Children's Crusade of 1212. The Latin Empire of Constantinople

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzant ...

was established, with the emperor Baldwin I essentially elected by the Venetians. (The imperial crown was at first offered to doge Enrico Dandolo

Enrico Dandolo (anglicised as Henry Dandolo and Latinized as Henricus Dandulus; c. 1107 – May/June 1205) was the Doge of Venice from 1192 until his death. He is remembered for his avowed piety, longevity, and shrewdness, and is known for his r ...

, who refused it.) The first Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, the Venetian Thomas Morosini

Thomas Morosini ( it, Tommaso Morosini; Venice, c. 1170/1175 – Thessalonica, June/July 1211) was the first Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, from 1204 to his death in July 1211. Morosini, then a sub-deacon, was elected patriarch by the Venet ...

, was contested by the pope as uncanonical.

The ongoing situation in Europe was chaotic. Philip of Swabia was locked in a dispute of the throne in Germany with Otto of Brunswick. Innocent III's attempts to reconcile their differences was rendered moot with Philip's assassination on 21 June 1208. Otto was crowned Holy Roman Emperor and fought against the pope, resulting in his excommunication. France was heavily invested in the Albigensian Crusade and was quarreling with John Lackland

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Empi ...

, resulting in the Anglo-French war

The Anglo-French Wars were a series of conflicts between England (and after 1707, Britain) and France, including:

Middle Ages High Middle Ages

* Anglo-French War (1109–1113) – first conflict between the Capetian Dynasty and the House of Norma ...

of 1213–1214. Sicily was ruled by the child-king Henry II and Spain was occupied in their crusade against the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire f ...

. There was little appetite in Europe for a new Crusade.

In Jerusalem, John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Champag ...

became the effective ruler of the kingdom through his marriage to Maria of Montferrat

Maria of Montferrat (1192–1212) was the queen of Jerusalem from 1205 until her death. Her parents were Isabella I and her second husband, Conrad of Montferrat. Maria succeeded her mother under the regency of her half-uncle John of Ibelin. After ...

. In 1212, Isabella II of Jerusalem

Isabella II (12124 May 1228), also known as Yolande of Brienne, was a princess of French origin, the daughter of Maria, the queen-regnant of Jerusalem, and her husband, John of Brienne. She was reigning Queen of Jerusalem from 1212 until her death ...

was proclaimed queen of Jerusalem shortly after her birth, and her father John became regent. Antioch was consumed with the War of the Antiochene Succession, begun with the death of Bohemond III

Bohemond III of Antioch, also known as Bohemond the Child or the Stammerer (french: Bohémond le Bambe/le Baube; 1148–1201), was Prince of Antioch from 1163 to 1201. He was the elder son of Constance of Antioch and her first husband, Raymond of ...

, not to be resolved until 1219.

Before the arrival of John of Brienne in Acre in 1210, the local Christians had refused to renew their truce the Ayyubids. The next year, John negotiated with the aging sultan al-Adil a new truce between the kingdom and the sultanate to last through 1217. At the same time, in light of the strength of the Muslims and their renewed fortifications, John also asked the pope for help. There was no real force among the Syrian Franks, with many of the deployed knights returning home. If a new Crusade were to begin, it must come from Europe.

Innocent III had hoped to mount such a Crusade to the Holy Land, never forgetting the goal of restoring Jerusalem to Christian control. The pathos of the Children's Crusade only nerved him to fresh efforts. But for Innocent, this tragedy had its moral: “the very children put us to shame, while we sleep they go forth gladly to conquer the Holy Land.”

Preparations for the Crusade

In April 1213, Innocent III issued his papal bull '' Quia maior'', calling all of Christendom to join a new Crusade. This was followed by a conciliar decree, the ''Ad Liberandam,'' in 1215. The attendant papal instructions engaged a new enterprise to recover Jerusalem while establishing Crusading norms that were to last nearly a century. The message of the Crusade was preached in France by legateRobert of Courçon

Robert of Courson or Courçon (also written de Curson, or Curzon, ''Princes of the Church'', p. 173.) ( 1160/1170 – 1219) was a scholar at the University of Paris and later a cardinal and papal legate.

Life

Robert of Courson was born in England ...

, a former classmate of the pope's. He was met with bitter complaints by the clergy, accusing the legate of encroaching on their domains. Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

supported his clergy, and Innocent III realized the Robert's zeal was a threat to the success of the Crusade. On 11 November 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council

The Fourth Council of the Lateran or Lateran IV was convoked by Pope Innocent III in April 1213 and opened at the Lateran Palace in Rome on 11 November 1215. Due to the great length of time between the Council's convocation and meeting, many bi ...

was convened. The prelates of France presented their grievances, many well-founded, and the pope pleaded for them to forgive the legate's indiscretions. In the end, very few Frenchmen took part in the expedition of 1217, unwilling to go in the company of Germans and Hungarians, with France represented by Aubrey of Reims and the bishops of Limoges and Bayeux, Jean de Veyrac and Robert des Ablèges.

At the council, Innocent III called for the recovery of the Holy Land. Innocent wanted it to be led by the papacy, as the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic r ...

should have been, to avoid the mistakes of the Fourth Crusade, which had been taken over by the Venetians. He planned to meet with the Crusaders at Brindisi and Messina for departure on 1 June 1217, and prohibited trade with the Muslims in order to ensure that the Crusaders would have ships and weapons, renewing an 1179 edict. Every Crusader would receive an indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God of ...

as well as those who simply helped pay the expenses of a Crusader, but did not go on the Crusade themselves.

In order to protect Raoul of Merencourt, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, on his return trip to the kingdom, Innocent III tasked John of Brienne to provide escort. As John was in conflict with Leo I of Armenia and Hugh I of Cyprus

Hugh I (french: Hugues; gr, Ούγος; 1194/1195 – 10 January 1218) succeeded to the throne of Cyprus on 1 April 1205 underage upon the death of his elderly father Aimery, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem. His mother was Eschiva of Ibelin, heir ...

, the pope ordered them to reconcile their differences before the Crusaders reached the Holy Land.

Innocent III died on 16 July 1216 and Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

was consecrated as pope the next week. The Crusade dominated the early part of his papacy. The next year, he crowned Peter II of Courtenay

Peter, also Peter II of Courtenay (french: Pierre de Courtenay; died 1219), was emperor of the Latin Empire of Constantinople from 1216 to 1217.

Biography

Peter II was a son of Peter I of Courtenay (died 1183), a younger son of Louis VI of Fra ...

as Latin Emperor, who captured on his eastward journey in Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

and died in confinement.

Robert of Courçon was sent as spiritual advisor to the French fleet, but subordinate to newly-chosen papal delegate Pelagius of Albano. Bishop Walter II of Autun, a veteran of the Fourth Crusade, would also return to the Holy Land with the Fifth Crusade. French canon Jacques de Vitry had come under the influence of the saintly Marie of Oignies and preached the Albigensian Crusade after 1210. He arrived at his new position as Bishop of Acre in 1216 and shortly thereafter Honorius III tasked him with preaching the Crusade in the Latin settlements of Syria, made difficult with the rampant corruption at the port cities.

Oliver of Paderborn Oliver of Paderborn, also known as Thomas Olivier, Oliver the Saxon or Oliver of Cologne ( 1170 – 11 September 1227), was a Germans, German cleric, crusader and chronicler. He was the bishop of Paderborn from 1223 until 1225, when Pope Honorius II ...

preached the Crusade in Germany and had great success in recruitment. In July 1216, Honorius III called on Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II ( hu, II. András, hr, Andrija II., sk, Ondrej II., uk, Андрій II; 117721 September 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1205 and 1235. He ruled the Principality of Halych from 11 ...

to fulfill his father's vow to lead a Crusade. Like many other rulers, the pope's former pupil, Frederick II of Germany

Frederick II (German: ''Friedrich''; Italian: ''Federico''; Latin: ''Federicus''; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerus ...

, had taken an oath to embark for the Holy Land in 1215 and appealed to German nobility to join. But Frederick II hung back, with his crown still in contention with Otto IV

Otto IV (1175 – 19 May 1218) was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1209 until his death in 1218.

Otto spent most of his early life in England and France. He was a follower of his uncle Richard the Lionheart, who made him Count of Poitou in 119 ...

, and Honorius repeatedly put off the date for the beginning of the expedition.

In Europe, the troubadours were equally adept in awakening the interest in the Crusade. These included Elias Cairel, a veteran of the Fourth Crusade, Pons de Capduelh

Pons de Capduelh (fl. 1160–1220Chambers 1978, 140. or 1190–1237Aubrey 1996, 19–20.) was a troubadour from the Auvergne, probably from Chapteuil. His songs were known for their great gaiety. He was a popular poet and 27 of his songs are prese ...

, later joining the Crusade in 1220, and Aimery de Pégulhan, who implored by verse a young William VI of Montferrat

William VI (c. 1173 – 17 September 1225) was the tenth Marquis of Montferrat from 1203 and titular King of Thessalonica from 1207.

Biography Youth

Boniface I's eldest son, and his only son by his first wife, Helena del Bosco, William stood o ...

to follow in his father's footsteps and take the cross.

The strength of the armies was estimated at more than 32,000, including more than 10,000 knights. It was described by a contemporaneous Arab historian as: "This year, an infinite number of warriors left from Rome the great and other countries of the West." The Crusader force was also prepared to use the latest siege technology, including counterweight trebuchets.

In Iberia and the Levant

The departure of the Crusaders began finally in early July 1217. Many of the Crusaders decided to go to the Holy Land by their traditional sea journey. The fleet made their first stop at Dartmouth on the southern coast of England. There they elected their leaders and the laws by which they would organize their venture. From there, led byWilliam I of Holland

William I (c. 1167 – 4 February 1222) was count of Holland from 1203 to 1222. He was the younger son of Floris III and Ada of Huntingdon.

Early life

William was born in The Hague, but raised in Scotland. He participated in the Third Cru ...

, they continued on their way south to Lisbon. As in previous crusading seaborne journeys, the fleet was dispersed by storms and only gradually managed to reach the Portuguese city of Lisbon after making a stopover at the famous shrine of Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

.

At their arrival in Portugal, the Bishop of Lisbon attempted to persuade the Crusaders to help them capture the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

controlled city of Alcácer do Sal

Alcácer do Sal () is a municipality in Portugal, located in Setúbal District. The population in 2011 was 13,046, in an area of 1499.87 km2.

History Earliest settlement

There has been human settlement in the area for more than 40,000 ye ...

. The Frisians, however, refused on account of Innocent III's disqualification of the venture at the Fourth Lateran Council. The other members of the fleet, however, were convinced by the Portuguese and started the siege of Alcácer do Sal in August 1217. The Crusaders finally captured the city with the help of the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

, on October 1217.

A group of Frisians who refused to aid the Portuguese with their siege plans against Alacácer do Sal, preferred to raid several coastal towns on their way to the Holy Land. They attacked Faro, Rota, Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

and Ibiza, gaining much booty thereby. They thereafter followed the coast of southern France and wintered in Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (; meaning "ancient town") is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Rome in the central Italian region of Lazio. A sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, it is located west-north-west of Rome. The harbour is formed by two pier ...

in Italy in 1217–1218, before continuing on their way to Acre. In the north, Ingi II of Norway took the cross in 1216, only to die the next spring, and the eventual Scandinavian expedition was of little consequence.

Innocent III had managed to secure the participation of the Kingdom of Georgia

The Kingdom of Georgia ( ka, საქართველოს სამეფო, tr), also known as the Georgian Empire, was a medieval Eurasian monarchy that was founded in circa 1008 AD. It reached its Golden Age of political and economic ...

in the Crusade. Tamar of Georgia

Tamar the Great ( ka, თამარ მეფე, tr, lit. "King Tamar") ( 1160 – 18 January 1213) reigned as the Queen of Georgia from 1184 to 1213, presiding over the apex of the Georgian Golden Age. A member of the Bagrationi dyna ...

, queen since 1184, led the Georgian state to its zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. Under her rule, Georgia challenged Ayyubid rule in eastern Anatolia. Tamar died in 1213 and was succeeded by her son George IV of Georgia

George IV, also known as Lasha Giorgi ( ka, ლაშა გიორგი) (1191–1223), of the Bagrationi dynasty, was a king of Georgia from 1213 to 1223.

Life

A son of Queen Regnant Tamar and her consort David Soslan, George was declared ...

. In the late 1210s, according to the Georgian chronicles, he began making preparations for a campaign in the Holy Land to support the Franks. His plans were cut short by the invasion of the Mongols in 1220. After the death of George IV, his sister Rusudan of Georgia

Rusudan ( ka, რუსუდანი, tr) (c. 1194–1245), a member of the Bagrationi dynasty, ruled as Queen of Georgia in 1223–1245.

Life

Daughter of King Tamar of Georgia by David Soslan, she succeeded her brother George IV on January ...

notified the pope that Georgia was unable to fulfill its promises.

The situation in the Holy Land

Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

had died in 1193 and was succeeded in most of his domain by his brother al-Adil, who was the patriarch of all successive Ayyubid sultans of Egypt. Saladin's son az-Zahir Ghazi

Al-Malik az-Zahir Ghiyath ud-din Ghazi ibn Yusuf ibn Ayyub (commonly known as az-Zahir Ghazi; 1172 – 8 October 1216) was the Ayyubid emir of Aleppo between 1186 and 1216.

retained his leadership in Aleppo. An exceptionally low Nile River resulted in a failure of the crops in 1201–1202, and famine and pestilence ensued. People abandoned themselves to atrocious practices, habitually resorting to cannibalism. Violent earthquakes, felt as far away as Syria and Armenia, devastated whole cities, and increased the general misery.

After naval raids on Rosetta

Rosetta or Rashid (; ar, رشيد ' ; french: Rosette ; cop, ϯⲣⲁϣⲓⲧ ''ti-Rashit'', Ancient Greek: Βολβιτίνη ''Bolbitinē'') is a port city of the Nile Delta, east of Alexandria, in Egypt's Beheira governorate. The Ro ...

in 1204 and Damietta in 1211, the chief concern of al-Adil was Egypt. He was willing to make concessions to avoid war, and favoured the Italian maritime states of Venice and Pisa, both for trading reasons and to preclude them from supporting further crusades. Most of his reign was conducted under truces with the Christians, and he constructed a new fortress at Mount Tabor

Mount Tabor ( he, הר תבור) (Har Tavor) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, west of the Sea of Galilee.

In the Hebrew Bible (Joshua, Judges), Mount Tabor is the site of the Battle of Mount Tabo ...

, to buttress the defenses of Jerusalem and Damascus. Most of his conflicts in Syria were with the Knights Hospitaller at Krak des Chevaliers

Krak des Chevaliers, ar, قلعة الحصن, Qalʿat al-Ḥiṣn also called Hisn al-Akrad ( ar, حصن الأكراد, Ḥiṣn al-Akrād, rtl=yes, ) and formerly Crac de l'Ospital; Krak des Chevaliers or Crac des Chevaliers (), is a medieva ...

or with Bohemond IV of Antioch

Bohemond IV of Antioch, also known as Bohemond the One-Eyed (french: Bohémond le Borgne; 1175–1233), was Count of Tripoli from 1187 to 1233, and Prince of Antioch from 1201 to 1216 and from 1219 to 1233. He was the younger son of Bohemond III ...

, and were dealt with by his nephew az-Zahir Ghazi. Only once, in 1207, did he directly confront the Crusaders, capturing al-Qualai'ah, besieging Krak des Chevaliers and advancing to Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, before accepting an indemnity from Bohemond IV in exchange for peace.

Az-Zahir maintained an alliance with both Antioch and Kaykaus I

Kaykaus I or Izz ad-Din Kaykaus ibn Kayhkusraw ( 1ca, كَیکاوس, fa, عز الدين كيكاوس پور كيخسرو ''ʿIzz ad-Dīn Kaykāwūs pour Kaykhusraw'') was the Sultan of Rum from 1211 until his death in 1220. He was the eldest ...

, the Seljuk sultan of Rûm, to check the influence of Leo I of Armenia, as well as to keep his options open to challenge his uncle. Az-Zahir died in 1216, leaving as his successor al-Aziz Muhammad

Al-Aziz Muhammad ibn Ghazi ( – 26 November 1236) was the Ayyubid Emir of Aleppo and the son of az-Zahir Ghazi and grandson of Saladin. His mother was Dayfa Khatun, the daughter of Saladin's brother al-Adil.

Al-Aziz was aged just three when ...

, his 3-year-old son, whose mother was Dayfa Khatun

Dayfa Khatun ( ar, ضيفة خاتون; died 1242) was Ayyubid princess, and the regent of Aleppo from 26 November 1236 to 1242, during the minority of her grandson An-Nasir Yusuf. She was an Ayyubid princess, as the daughter of Al-Adil, Sult ...

, al-Adil's daughter. Saladin's eldest son, al-Afdal, emerged to make a bid for Aleppo, enlisting the help of Kaykaus I, who also had designs on the region. In 1218, al-Afdal and Kaykaus invaded Aleppo and advanced on the capital. The situation was resolved when al-Ashraf, al-Adil's third son, routed the Seljuk army, which remained a menace until the death of Kaykaus in 1220. Given the Crusaders’ Egyptian plan, these diversions were useful in stretching the resources of the sultanate that controlled the Levant with an uneasy cooperation.

Crusade of Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II had been called on by the pope in July 1216 to fulfill his father Béla III's vow to lead a crusade, and finally agreed, having postponed three times earlier. Andrew, who was reputed to have designs on becoming Latin emperor, mortgaged his estates to finance the Crusade. In July 1217, he departed fromZagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital and largest city of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb stands near the international border between Croatia and Slov ...

, accompanied by Leopold VI of Austria

Leopold VI (15 October 1176 – 28 July 1230), known as Leopold the Glorious, was Duke of Styria from 1194 and Duke of Austria from 1198 to his death in 1230. He was a member of the House of Babenberg.

Biography

Leopold VI was the younger son ...

and Otto I, Duke of Merania

Otto I (c. 1180 – 7 May 1234), a member of the House of Andechs, was Duke of Merania from 1204 until his death. He was also Count of Burgundy (as Otto II) from 1208 to 1231, by his marriage to Countess Beatrice II, and Margrave of Istria and ...

. They were transported by the Venetian fleet, the largest European fleet of the times. Andrew and his troops embarked from Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

on 23 August 1217.

The Hungarian army landed on 9 October 1217 on

The Hungarian army landed on 9 October 1217 on Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

from where they sailed to Acre and joined John of Brienne, Raoul of Merencourt and Hugh I of Cyprus

Hugh I (french: Hugues; gr, Ούγος; 1194/1195 – 10 January 1218) succeeded to the throne of Cyprus on 1 April 1205 underage upon the death of his elderly father Aimery, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem. His mother was Eschiva of Ibelin, heir ...

. In October 1217, the leaders of the expedition held a war council there, presided by Andrew II. Representing the military orders were the masters Guérin de Montaigu

Guérin de Montaigu (died 1228), also known as Garin de Montaigu or Pierre Guérin de Montaigu, was a nobleman from Auvergne, who became the fourteenth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, serving from 1207–1228. He succeeded the Grand Mast ...

of the Hospitallers, Guillaume de Chartres of the Templars, and Hermann of Salza

Hermann von Salza (or Herman of Salza; c. 1165 – 20 March 1239) was the fourth Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, serving from 1210 to 1239. A skilled diplomat with ties to the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, Hermann oversaw the expans ...

of the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

. Additional attendees included Leopold VI of Austria, Otto I of Merania, Walter II of Avesnes Walter II of Avesnes (b. 1170 – d.1244) was lord of Avesnes, Leuze, of Condé and Guise, and through his marriage to Margaret of Blois, he became count of Blois and Chartres. He was the son of James of Avesnes, and Adèle, lady of Guise.

Wa ...

, and numerous archbishops and bishops.

The war plan of John of Brienne envisioned a two-prong attack. In Syria, Andrew's forces would engage al-Mu'azzam, son of Al-Adil, at the stronghold of Nablus. At the same time, the fleet was to attack the port city of Damietta

Damietta ( arz, دمياط ' ; cop, ⲧⲁⲙⲓⲁϯ, Tamiati) is a port city and the capital of the Damietta Governorate in Egypt, a former bishopric and present multiple Catholic titular see. It is located at the Damietta branch, an easter ...

, wresting Egypt from the Muslims and enabling the conquest of the remainder of Syria and Palestine. This plan was abandoned at Acre due to the lack of manpower and ships. Instead, in anticipation of reinforcements, the objective was to keep the enemy occupied in a series of small engagements, perhaps going as far as Damascus.

The Muslims knew that the Crusaders were coming in 1216 with the exodus of merchants from Alexandria. Once the host gathered at Acre, Al-Adil began operations in Syria, leaving the bulk of his forces in Egypt under his eldest son and viceroy Al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cr ...

. He personally led a small contingent to support al-Mu'azzam, then emir of Damascus

This is a list of rulers of Damascus from ancient times to the present.

:''General context: History of Damascus''.

Aram Damascus

* Rezon I (c. 950 BC)

* Tabrimmon

*Ben-Hadad I (c. 885 BCE–c. 865 BC)

*Hadadezer (c. 865 BC–c. 842 BC)

*Hazael ( ...

. With too few to engage the Crusaders, he guarded the approaches to Damascus while al-Mu'azzam was sent to Nablus to protect Jerusalem.

The Crusaders were camped near Acre at Tel Afek

Tel Afek, ( he, תל אפק), also spelled Aphek and Afeq, is an archaeological site located in the coastal hinterland of the Ein Afek Nature Reserve, east of Kiryat Bialik, Israel. It is also known as Tel Kurdani.

History Antiquity

The site ...

, and on 3 November 1217 began to traverse the plain of Esdraelon towards 'Ain Jalud, expecting an ambush. Upon seeing the strength of the Crusaders, al-Adil withdrew to Beisan against the wishes of al-Mu'azzam who wanted to attack from the heights of Nain. Again against the wishes of his son, Al-Adil abandoned Beisan which soon fell to the Crusaders who pillaged the city. He continued his retreat to Ajlun

Ajloun ( ar, عجلون, ''‘Ajlūn''), also spelled Ajlun, is the capital town of the Ajloun Governorate, a hilly town in the north of Jordan, located 76 kilometers (around 47 miles) north west of Amman. It is noted for its impressive ruins of t ...

, ordering al-Mu'azzam to protect Jerusalem from the heights of Lubban, near Shiloh. Al-Adil continued to Damascus, stopping at Marj al-Saffar.

On 10 November 1217, the Crusaders crossed the Jordan River at the Jisr el-Majami

Jisr el-Majami or Jisr al-Mujamieh ( ar, جسر المجامع, Jisr al-Majami, Meeting Bridge or "The bridge of the place of assembling", and he, גֶּשֶׁר, ''Gesher'', lit. "Bridge") is an ancient stone bridge, possibly of Roman origin, o ...

, threatening Damascus. The governor of the city took defensive measures, and received reinforcements from al-Mujahid Shirkuh, the Ayyubid emir of Homs. Without engaging the enemy, the Crusaders returned to the camp near Acre, crossing over Jacob's Ford. Andrew II did not return to the battlefield, preferring to remain in Acre collecting relics.

Now under the command of John of Brienne, as supported by Bohemond IV, the Hungarians moved against Mount Tabor

Mount Tabor ( he, הר תבור) (Har Tavor) is located in Lower Galilee, Israel, at the eastern end of the Jezreel Valley, west of the Sea of Galilee.

In the Hebrew Bible (Joshua, Judges), Mount Tabor is the site of the Battle of Mount Tabo ...

, regarded by the Muslims as impregnable. A battle fought on 3 December 1217 was soon abandoned by the leaders, only to be revisited by the Templars and Hospitallers. Met with Greek fire, the siege was abandoned on 7 December 1217. A third sortie by the Hungarians, possibly led by Andrew's nephew, met disaster at Mashghara. The small force was decimated, and the few survivors returned to Acre on Christmas Eve. Thus ended what is known as the Hungarian Crusade of 1217.

At the beginning of 1218, an ailing Andrew decided to return to Hungary, under the threat of excommunication. Andrew and his army departed to Hungary in February 1218, stopping first at Tripoli for the marriage of Bohemond IV and Melisende of Lusignan

Melisende of Cyprus (1200 Holy Land- after 1249), was the youngest daughter of Queen Isabella I of Jerusalem by her fourth and last marriage to King Aimery of Cyprus. She had a sister Sibylla of Lusignan, a younger brother, Amalric who died as a ...

. Hugh I of Cyprus, accompanying his fellow commanders, became ill at the ceremony and died shortly thereafter. Andrew returned to Hungary in late 1218.

In the meantime, efforts were taken to strengthen Château Pèlerin, by the Templars and aided by Walter II of Aveses, and Caesarea which proved later to be valuable moves. Later in the year, Oliver of Paderborn Oliver of Paderborn, also known as Thomas Olivier, Oliver the Saxon or Oliver of Cologne ( 1170 – 11 September 1227), was a Germans, German cleric, crusader and chronicler. He was the bishop of Paderborn from 1223 until 1225, when Pope Honorius II ...

arrived with a new German army and William I of Holland

William I (c. 1167 – 4 February 1222) was count of Holland from 1203 to 1222. He was the younger son of Floris III and Ada of Huntingdon.

Early life

William was born in The Hague, but raised in Scotland. He participated in the Third Cru ...

arrived with a mixed army consisting of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

and Frisian soldiers. As it became clear that Frederick II was not coming to the East, they began detailed planning. The campaign was to be led by John of Brienne, based on his status in the kingdom and his proven military reputation. The original objective abandoned the year before due to lack of resources was reinstated. The decision to attack Egypt had been made, a springtime assault on Jerusalem rejected because of excessive heat and lack of water. They focused their main thrust on the port of Damietta rather than Alexandria. The European Crusader army was supplemented by troops from the kingdom and the military orders.

The campaign in Egypt

On 27 May 1218, the first of the Crusader's fleet arrived at the harbor of Damietta, on the right bank of the Nile.The Fifth Crusade, 1218–1221Map by the University of Wisconsin Cartography Laboratory, facing pg. 487 of Volume II of ''A History of the Crusades'' (Setton, editor) Simon III of Sarrebrück was chosen as temporary leader pending the arrival of the rest of the fleet. Within a few days, the remaining ships arrived, carrying John of Brienne, Leopold VI of Austria and masters

Peire de Montagut

Peire de Montagut Known in Catalan as Pere de Montagut and in French as Pierre de Montaigu. (? – 28 January 1232) was Grand Master of the Knights Templar from 1218 to 1232. He took part in the Fifth Crusade and was against the Sultan of Egyp ...

, Hermann of Salza

Hermann von Salza (or Herman of Salza; c. 1165 – 20 March 1239) was the fourth Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, serving from 1210 to 1239. A skilled diplomat with ties to the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, Hermann oversaw the expans ...

and Guérin de Montaigu

Guérin de Montaigu (died 1228), also known as Garin de Montaigu or Pierre Guérin de Montaigu, was a nobleman from Auvergne, who became the fourteenth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, serving from 1207–1228. He succeeded the Grand Mast ...

. A lunar eclipse on 9 July was viewed as a good omen.

The Muslims were not alarmed at the arrival of the Crusaders, believing that they would not successfully mount an attack on Egypt. Al-Adil was both surprised and disappointed in the West, supporting peace treaties when more radical elements in the sultanate sought ''jihad''. He was still camped at Marj al-Saffar, and his sons al-Kamil

Al-Kamil ( ar, الكامل) (full name: al-Malik al-Kamil Naser ad-Din Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad) (c. 1177 – 6 March 1238) was a Muslim ruler and the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. During his tenure as sultan, the Ayyubids defeated the Fifth Cr ...

and al-Mu'azzam were tasked with defending Cairo and the Syrian coast, respectively. Available reinforcements were sent from Syria, and an Egyptian force encamped at al-'Adiliyah, a few miles south of Damietta. The Egyptians were of insufficient strength to attack the Crusaders, but did serve to oppose any invader attempt to cross the Nile.

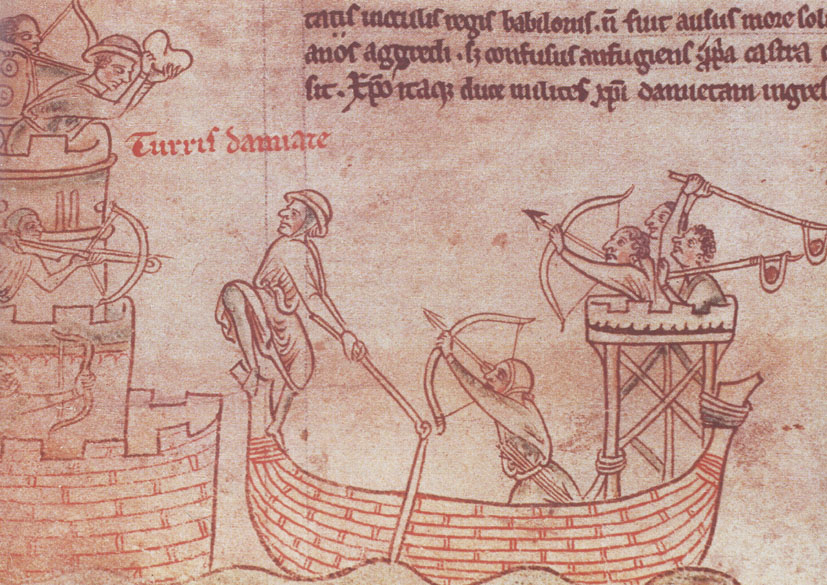

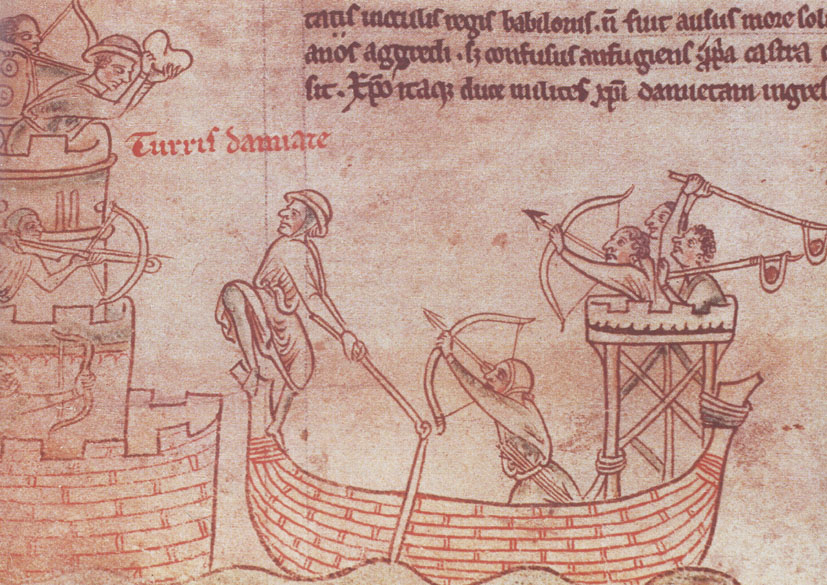

The Tower of Damietta

The fortifications of Damietta were impressive, consisting of three walls of varying heights, with dozens of towers on the interior, and were enhanced to repel the invaders. Situated on an island in the Nile was the ''Burj al-Silsilah––''the chain tower––called so because of the massive iron chains that could stretch across the river preventing passage. The tower, containing 70 tiers and housing hundreds of soldiers, was key to the capture of the city. The siege of Damietta began on 23 June 1218 with an assault on the tower, utilizing upwards of 80 ships some with projectile machines, with no success. Two new types of vessels were adapted to meet the needs of the siege. The first, used by Leopold VI and the Hospitallers, was able to secure scaling ladders mounted on two ships bound together. The second, called a ''maremme'', was commanded byAdolf VI of Berg

Count Adolf VI of Berg (born before 1176 – died 7 August 1218 at Damiette during the Hungarian crusade against Egypt) ruled the County of Berg from 1197 until 1218.

Life

He was the son of Engelbert I of Berg and Margaret of Geldern, and t ...

and included a small fortress on the mast to hurl stones and javelins. The ''maremme'', attacking first, was forced to withdraw when faced with an intense counter-barrage. The scaling ladders, secured against the walls, collapsed under the weight of the soldiers. The first attempt at an assault was a failure.

Oliver of Paderborn Oliver of Paderborn, also known as Thomas Olivier, Oliver the Saxon or Oliver of Cologne ( 1170 – 11 September 1227), was a Germans, German cleric, crusader and chronicler. He was the bishop of Paderborn from 1223 until 1225, when Pope Honorius II ...

, supported by his Frisian and German followers, demonstrating considerable ingenuity and leadership, constructed an ingenious siege engine combining the best features of the earlier models. Protected from Greek fire by hides, it included a revolving ladder that extended far beyond the ship. On 24 August the renewed assault began. By the next day, the tower was taken and the defensive chains cut.

The loss of the tower was a great shock to the Ayyubids, and the sultan al-Adil died shortly thereafter, on 31 August 1218. His body was secretly taken to Damascus and his treasure dispersed before his death was announced. He was succeeded as sultan by his son al-Kamil. The new sultan immediately implemented defensive measures, including scuttling a number of ships a mile upstream, resulting in the Nile being blocked for much of the winter of 1218–1219.

Preparation for the siege

The Crusaders did not press their advantage, and many prepared to return home, regarding their crusading vows satisfied. Further offensive action would nevertheless have to wait until the Nile was more favourable and the arrival of additional forces. Among them were papal legate Pelagius Galvani and his aide Robert of Courçon, who travelled with a contingent of Roman Crusaders financed by the pope. A group from England, smaller than expected arrived shortly, led by Ranulf de Blondeville, and Oliver andRichard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

, illegitimate sons of John Lackland

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Empi ...

. A group of French Crusaders that arrived at the end of October included Guillaume II de Genève, archbishop of Bordeaux, and the newly elected bishop of Beauvais, Milo of Nanteuil

Milo of Nanteuil (french: Milon or ) was a French cleric and crusader. He served as the provost of the cathedral of Reims from 1207 to 1217 and then as bishop Beauvais from 1218 until his death in September 1234.

Milo was the fourth son of Gau ...

.

On 9 October 1218, Egyptian forces conducted a surprise attack on the Crusaders' camp. Discovering their movements, John of Brienne and his retinue attacked and annihilated the Egyptian advance guard, hindering the main force. From the outset, Pelagius considered himself the supreme commander of the Crusade, and, unable to mount a major offensive, sent specially equipped ships up the Nile to no avail. A follow-on attack on the Crusaders on 26 October also failed, as did a Crusader attempt to dredge an abandoned canal, the al-Azraq, to bypass al-Kamil's new defensive measures on the Nile.

The Crusaders now built an enormous floating fortress on the river, but a storm the began on 9 November 1218 blew it near the Egyptian camp. The Egyptians seized the fortress, killing nearly all of its defenders. Only two soldiers survived the attack. They were accused of cowardice, and John ordered their execution. The storm, lasting 3 days, flooded both camps and the Crusaders' supplies and transportation were devastated. In the ensuing months diseases killed many of the Crusaders, including Robert of Courçon. During the storm, Pelagius took control of the expedition. The Crusaders supported this, feeling the need for new, more aggressive leadership. By February 1219, they were able to mount new offensives, but were unsuccessful because of the weather and strength of the defenders.

At this time, al-Kamil, in command of the defenders, when he was almost overthrown by a coup to replace him with his younger brother al-Faiz Ibrahim. Alerted to the conspiracy, al-Kamil had to flee the camp to safety and in the ensuing confusion the Crusaders were able to advance on Damietta. Al-Kamil considered fleeing to the Ayyubid emirate of Yemen, ruled by his son al-Mas'ud Yusuf, but the arrival of his brother al-Mu'azzam with reinforcements from Syria ended the conspiracy. The Crusader attack mounted against the Egyptians on 5 February 1219 was then different, the defenders having fled, abandoning the camp.

The Crusaders now surrounded Damietta, with the Italians to the north, Templars and Hospitallers to the east, and John of Brienne with his French and Pisan troops to the south. The Frisians and Germans occupied the old camp across the river. A new wave of reinforcements from Cyprus arrived led by Walter III of Caesarea

Walter III (French: ''Gautier''), sometimes called Walter de Brisebarre or Walter Grenier (bef. 1180 – 24 June 1229), was the Constable of the Kingdom of Cyprus from 1206 and Lord of Caesarea in the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1216. He was the eld ...

.

At this point, al-Kamil and al-Mu'azzam attempted to open negotiations with the Crusaders, asking Christian envoys to come to their camp. They offered to surrender the kingdom of Jerusalem, less al-Karak

Al-Karak ( ar, الكرك), is a city in Jordan known for its medieval castle, the Kerak Castle. The castle is one of the three largest castles in the region, the other two being in Syria. Al-Karak is the capital city of the Karak Governorate. ...

and Krak de Montréal which guarded to road to Egypt, with a multi-year truce, in exchange for the Crusaders' evacuation of Egypt. John of Brienne and the other secular leaders were in favour of the offer, as the original objective of the Crusade was the recovery of Jerusalem. But Pelagius and the leaders of the Templars, Hospitallers and Venetians refused this and a subsequent offer with compensation for the fortresses, damaging the unity of the enterprise. Al-Mu'azzam responded by reorganizing his reinforcements at Fariskur, upriver from al-'Adiliyah. Unknown to the Crusaders, Damietta could have been easily taken at this point due to illness and death among the defenders.

In the Holy Land, al-Mu'azzam's forces began dismantling fortifications at Mount Tabor and other defensive positions, as well as Jerusalem itself, in order to deny their protection should the Crusaders prevail there. Al-Muzaffar II Mahmud

Al-Muzaffar II Mahmud was the Ayyubid emir of Hama first in 1219 (616 AH) and then restored in 1229–1244 (626 AH–642 AH). He was the son of al-Mansur Muhammad and the older brother of al-Nasir Kilij Arslan.

Usurpation

In 1219, al-Mansur cal ...

, the son of the Ayyubid emir of Hama (and later emir himself), arrived in Egypt with Syrian reinforcements, leading multiple attacks on the Crusader camp through 7 April 1219, with little impact. In the meantime, Crusaders such as Leopold VI of Austria were returning to Europe, but were more than offset by new recruits, including Guy I Embriaco, who brought badly-needed supplies. Muslim attacks continued through May, with Crusader counterattacks utilizing a Lombardy device known as a ''carroccio

A carroccio (; ) was a large four-wheeled wagon bearing the city signs around which the militia of the medieval communes gathered and fought. It was particularly common among the Lombard, Tuscan and, more generally, northern Italian municipali ...

'', confounding the defenders.

Despite objections from the military leaders, Pelagius began multiple attacks on the city on 8 July 1219 using Pisan and Venetian troops. Each time they were repelled by the defenders, using Greek fire. A counteroffensive by the Egyptians on the Templar camp on 31 July was repulsed by their new leader Peire de Montagut

Peire de Montagut Known in Catalan as Pere de Montagut and in French as Pierre de Montaigu. (? – 28 January 1232) was Grand Master of the Knights Templar from 1218 to 1232. He took part in the Fifth Crusade and was against the Sultan of Egyp ...

, supported by the Teutonic Knights. Fighting continued into August when the waters of the Nile receded. An attack on the sultan's camp at Fariskur on 29 August led by Pelagius' faction was a disaster, resulting in high losses for the Crusaders. The Marshal of the Hospitaller, Aymar de Lairon, and many Templars were killed. Only the intervention by John of Brienne, Ranulf de Blondeville, and the Templars and Hospitallers prevented further loss.

In August 1219, the sultan again offered peace, possibly out of desperation, using recent captives as envoys to the Christians. This included his earlier provisions plus paying for the restoration of the damaged fortifications, the return of the portion of the True Cross lost at the battle of Hattin and the release of prisoners. Again, his offer was rejected along familiar lines. Pelagius' view that victory was possible was supported by the continued arrival of new Crusades, most notably an English force led by Savari de Mauléon

Savari de Mauléon (also Savaury) ( oc, Savaric de Malleo) (died 1236) was a French soldier, the son of Raoul de Mauléon, Viscount of Thouars and Lord of Mauléon.

Having espoused the cause of Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, he was captured at ...

, a seneschal of the late John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Emp ...

.

Saint Francis in Egypt

In September 1219, Francis of Assisi arrived in the Crusader camp seeking permission from Pelagius to visit sultan al-Kamil. Francis had a long history with the Crusades. In 1205, Francis prepared to enlist in the army of

In September 1219, Francis of Assisi arrived in the Crusader camp seeking permission from Pelagius to visit sultan al-Kamil. Francis had a long history with the Crusades. In 1205, Francis prepared to enlist in the army of Walter III of Brienne

Walter III of Brienne (french: Gautier, it, Gualtiero; died June 1205) was a nobleman from northern France. Becoming Count of Brienne in 1191, Walter married the Sicilian princess Elvira and took an army to southern Italy to claim her inheritanc ...

(brother of John), diverted from the Fourth Crusade to fight in Italy. He returned to a life of the mendicants, later meeting with Innocent III who approved his religious order. After the Christian victory at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, known in Islamic history as the Battle of Al-Uqab ( ar, معركة العقاب), took place on 16 July 1212 and was an important turning point in the ''Reconquista'' and the medieval history of Spain. The Chris ...

in 1212, he travelled to meet with Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

caliph Muhammad an-Nāsir, ostensibly to convert him to Christianity. Francis did not make it to Morocco, only getting as far as Santiago de Compostela

Santiago de Compostela is the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The city has its origin in the shrine of Saint James the Great, now the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as the destination of the Way of S ...

, he returned, sickened, but with a mission. His fabled experience with the wolf of Gubbio exemplified his view of the power of the cross.

Initially refusing the request, Pelagius granted Francis and his companion, Illuminato da Rieti

Illuminatus of Arce ( it, Illuminato dell'Arce) or Illuminatus of Rieti (''Illuminato da Rieti'') was an earlier follower of Francis of Assisi.

Illuminatus was born around 1190, probably in Rocca Antica or Rocca Sinibalda, villages southwest of ...

, to go on what was assumed to be a suicide mission. They crossed over to preach to al-Kamil, who assumed that the holy men were emissaries of the Crusaders and received them courteously. When he discovered that their intent was instead to preach the evils of Islam, some in his court demanded the execution of the friars. Al-Kamil instead heard them out and had them escorted back to the Crusader camp. Francis did obtain a commitment for more humane treatment for the Christian captives. It was claimed in a sermon by Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; it, Bonaventura ; la, Bonaventura de Balneoregio; 1221 – 15 July 1274), born Giovanni di Fidanza, was an Italian Catholic Franciscan, bishop, cardinal, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister G ...

that the sultan converted or accepted a death-bed baptism as a result of his meeting with Francis.

Francis remained in Egypt through the fall of Damietta, departing then for Acre. While there, he established the Province of the Holy Land, a priory of the Franciscan Order, obtaining for the friars the foothold they still retain as guardians of the holy places.

The Siege of Damietta

With the negotiations with the Crusaders stalled and Damietta isolated, on 3 November 1219 al-Kamil sent a resupply convoy through the sector manned by the troops of the FrenchmanHervé IV of Donzy

Hervé IV of Donzy (1173– 22 January 1222) was a French nobleman and participant in the Fifth Crusade. By marriage in 1200 to Mahaut de Courtenay (1188–1257), daughter of Peter II of Courtenay, he became Count of Nevers.

In a dispute over th ...

. The Egyptians were by and large stopped, some getting through to the city, resulting in the expulsion of Hervé. The intrusion energized the Crusaders with a unity of purpose.

On 5 November 1219, suspecting the city had been vacated, the Crusaders entered Damietta and found it abandoned, filled with the dead and with most of the remaining citizens ill. Seeing the Christian banners flying over the city, al-Kamil moved his host from Fariskur downriver to Mansurah. Survivors in the city were either sent into slavery or held as hostage to trade for Christian prisoners.

The fortifications of Damietta were essentially undamaged, and the victorious Crusaders claimed much booty. By 23 November 1219, they had captured the neighboring city of Tinnis

Tennis or Tinnīs ( arz, تنيس, cop, ⲑⲉⲛⲛⲉⲥⲓ) was a medieval city in Egypt which no longer exists. It was most prosperous from the 9th century to the 11th century until its abandonment. It was located at 31°12′N 32°14′E, o ...

, on the Tanitic mouth of the Nile, providing access to the food sources of Lake Manzala

Lake Manzala ( ar, بحيرة المنزلة ''baḥīrat manzala''), also Manzaleh, is a brackish lake, sometimes called a lagoon, in northeastern Egypt on the Nile Delta near Port Said and a few miles from the ancient ruins at Tanis.Dinar, p.51 ...

.

As usual, there was partisan struggles as to the rule of the city, secular or ecclesiastic. At some point, John of Brienne had enough, equipping three ships for departure. Pelagius relented, allowing John to lead Damietta pending a decision by the pope. Nevertheless, the Italians, feeling deprived of booty, took arms against the French and expelled them from the city. Not until 2 February 1220 did the situation stabilize, with a formal ceremony conducted to celebrate the Christian victory. John soon departed for the Holy Land, either piqued at Pelagius or to stake his claim to Armenia. Either way, Honorius III soon decided Damietta's fate in favour of his legate Pelagius.

Among the casualties of the campaign for Damietta were Oliver, son of John Lackland, Milo IV of Puiset and his son Walter, and Hugh IX of Lusignan

Hugh IX "le Brun" of Lusignan (1163/1168 – 5 November 1219) was the grandson of Hugh VIII. His father, also Hugh (b. c. 1141), was the co-seigneur of Lusignan from 1164, marrying a woman named Orengarde before 1162 or about 1167 and dying i ...

. Templar Guillaume de Chartres died of the plague before the siege began.

John of Brienne returns to Jerusalem

The father-in-law of John of Brienne, Leo I of Armenia, died on 2 May 1219, leaving his succession in doubt. John's claim to the Armenian throne was through his wife Stephanie of Armenia and their infant son, and Leo I had instead left the kingdom to his infant daughterIsabella of Armenia

Isabella ( hy, Զապել; 27 January 1216/ 25 January 1217 – 23 January 1252), also Isabel or Zabel, was queen regnant of Armenian Cilicia from 1219 until her death in 1252.

She was proclaimed queen under the regency of Adam of Baghras. Aft ...

. The pope decreed in February 1220 that John was the rightful heir to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. John left Damietta for Jerusalem around Easter 1220 in order to assert his claim to his inheritance. His departure had been rumored to be due to desertion which was not the case.

Stephanie and their son died shortly after John's arrival, ending his claim to Cilicia. When Honorius III learned of their deaths, he declared Raymond-Roupen

Raymond-Roupen (also Raymond-Rupen and Ruben-Raymond; 1198 – 1219 or 1221/1222) was a member of the House of Poitiers who claimed the thrones of the Principality of Antioch and Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. His succession in Antioch was preve ...

(whom Leo I had disinherited) the lawful ruler, threatening John with excommunication if he fought for Cilicia. To solidify his position, Raymond-Roupen travelled to Damietta in the summer of 1220 to meet with Pelagius.

After Damietta was captured, Walter of Caesarea had brought 100 Cypriote knights and their men-at-arms, including a Cypriote knight named Peter Chappe, and his charge, a young Philip of Novara

Philip of Novara (c. 1200 – c. 1270) was a medieval historian, warrior, musician, diplomat, poet, and lawyer. born at Novara, Italy, into a noble house, who spent his entire adult life in the Middle East. He primarily served the Ibelin famil ...

. While in Egypt, Philip received instruction from the jurisconsult Ralph of Tiberias Raoul of Saint Omer, Raoul of Tiberias or Ralph of Tiberias (died 1220) was briefly Prince of Galilee and twice Seneschal of Jerusalem of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. His father was Walter of Saint Omer, his mother Eschiva of Bures. She remarried Ra ...

. In John's absence, Pelagius left the sea routes between Damietta and Acre unguarded, and a Muslim fleet attacked the Crusaders in the port of Limassol, resulting in over a thousand casualties. Most of the Cypriotes departed Egypt at the same time as John. When he returned, he passed through Cyprus and brought some forces with him.

John remained in Jerusalem for several months, primarily due to lack of funds. Since his nephew Walter IV of Brienne

Walter IV (french: Gauthier (1205–1246) was the count of Brienne from 1205 to 1246.

Life

Walter was the son of Walter III of Brienne and Elvira of Sicily. Around the time of his birth, his father lost his bid for the Sicilian throne and died i ...

was approaching the age of majority, John surrendered the County of Brienne

The County of Brienne was a medieval county in France centered on Brienne-le-Château.

Counts of Brienne

* Engelbert I

* Engelbert II

* Engelbert III

* Engelbert IV

* Walter I (? – c. 1090)

* Erard I (c. 1090 – c. 1120?)

* Walter I ...

to him in 1221. John returned to Egypt and rejoined the Crusade on 6 July 1221 at the direction of the pope.

Disaster at Mansurah

The situation in Damietta after the February 1220 celebration was one of inactivity and discontent. The army lacked discipline despite Pelagius' draconian rule. His extensive regulations prevented adequate protection of the shipping lanes from Cyprus, and several ships carrying pilgrims were sunk. Many Crusaders departed, but were supplement by fresh troops including contingents led by the archbishop of Milan, Enrico da Settala, and the unnamed archbishop of Crete. This was the prelude to the disastrous battle of Mansurah of 1221 that would end the Crusade. Late in 1220 or early in 1221, al-Kamil sentFakhr ad-Din ibn as-Shaikh Fakhr al-Din ibn al-Shaykh (before 1211 – 8 February 1250) was an Egyptian emir of the Ayyubid dynasty. He served as a diplomat for sultan al-Kamil from 1226 to 1228 in his negotiations with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II leading to the end ...

on an embassy to the court of al-Kamil's brother al-Ashraf, now ruling greater Armenia from Sinjar

Sinjar ( ar, سنجار, Sinjār; ku, شنگال, translit=Şingal, syr, ܫܝܓܪ, Shingar) is a town in the Sinjar District of the Nineveh Governorate in northern Iraq. It is located about five kilometers south of the Sinjar Mountains. Its p ...

, to request assistance against the Crusaders. He was at first refused. The Muslim world was now threatened also by the Mongols in Persia. When Abbasid caliph al-Nasir requested troops from al-Ashraf, however, the latter chose instead to send them assist his brother in Egypt. The Ayyubids regarded the Mongol ouster of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, shah of the Khwarazmians, as destroying one of their main enemies, allowing them to focus on the invaders at Damietta.

In the captured city, Pelagius was unable to prod the Crusaders from their inactivity through the year 1220, save for a Templar raiding party on Burlus in July 1220. The town was pillaged, but at the cost of the loss and capture of numerous knights. The relative calm in Egypt enabled al-Mu'azzam, returning to Syria after the defeat at Damietta, to attack the remaining coastal strongholds, taking Caesarea. By October, he had further degraded the defenses of Jerusalem and unsuccessfully attacking Château Pèlerin, defended by Peire de Montagut

Peire de Montagut Known in Catalan as Pere de Montagut and in French as Pierre de Montaigu. (? – 28 January 1232) was Grand Master of the Knights Templar from 1218 to 1232. He took part in the Fifth Crusade and was against the Sultan of Egyp ...

and his Templars, recently released from their duty in Egypt.

Al-Kamil took advantage of this lull to reinforce Mansurah, once a small camp, into a fortified city that could perhaps replace Damietta as the protector of the mouth of the Nile. At some point, he renewed his peace offering to the Crusaders. Again it was refused, with Pelagius' view that he held the key to conquering not only Egypt but also Jerusalem. In December 1220, Honorius III announced that Frederick II would soon be sending troops, expected now in March 1221, with the newly crowned emperor leaving for Egypt in August. Some troops did arrive in May, led by Louis I of Bavaria and his bishop, Ulrich II of Passau, and under orders not to begin offensive operations until Frederick arrived.

Even before the capture of Damietta, the Crusaders became aware of a book, written in Arabic, which claims to have predicted Saladin's earlier capture of Jerusalem and the impending Christian capture of Damietta. Based on this and other prophetic works, rumors circulated of a Christian uprising against the power of Islam, influencing the consideration of al-Kamil's peace offerings. Then in July 1221, rumors began that the army of one King David, a descendant of the legendary Prester John

Prester John ( la, Presbyter Ioannes) was a legendary Christian patriarch, presbyter, and king. Stories popular in Europe in the 12th to the 17th centuries told of a Nestorian patriarch and king who was said to rule over a Christian nation lost ...

, was on its way from the east to the Holy Land to join the Crusade and gain release of the sultan's Christian captives. The story soon grew to such proportions and generated so much excitement among the Crusaders that it led them to prematurely launch an attack on Cairo.

On 4 July 1221 Pelagius, having decided to advance to the south, ordered a three-day fast in preparation for the advance. John of Brienne, arriving in Egypt shortly thereafter, argued against the move, but was powerless to stop it. Already deemed a traitor for opposing the plans and threatened with excommunication, John joined the force under the command of the legate. They moved towards Fariskur on 12 July where Pelagius drew it up in battle formation.

The Crusader force advanced to Sharamsah, half-way between Fariskur and Mansurah on the east bank of the Nile, occupying the city on 12 July 1221. John of Brienne again attempted to turn the legate back, but the Crusader force was intent on gaining great booty from Cairo, and John would likely have been put to death if he persisted. On 24 July, Pelagius moved his forces near the al-Bahr as-Saghit (Ushmum canal), south of the village of Ashmun al-Rumman, on the opposite bank from Mansurah. His plan was to maintain supply lines with Damietta, not bringing sufficient food for his large army.

The fortifications established were less than ideal, made worse by the reinforcements the Egyptians brought in from Syria. Alice of Cyprus and the leaders of the military orders warned Pelagius of the large numbers of Muslims troops arriving and continued warnings from John of Brienne went unheeded. Many Crusaders took this opportunity to retreat back to Damietta, later departing for home.

The Egyptians had the advantage of knowing the terrain, especially the canals near the Crusader camp. One such canal near Barāmūn (see maps of the area here and here) could support large vessels in late August when the Nile was at its crest, and they brought numerous ships up from al-Maḥallah. Entering the Nile, they were able to block the Crusaders' line of communications to Damietta, rendering their position untenable. In consultation with his military leaders, Pelagius ordered a retreat, only to find the route to Damietta blocked by the sultan's troops.

On 26 August 1221, the Crusaders attempted to reach Barāmūn under the cover of darkness, but their carelessness alerted the Egyptians who set on them. They were also reluctant to sacrifice their stores of wine, drinking them rather than leave them. In the meantime, al-Kamil had the sluices along the right bank of the Nile opened, flooding the area and rendering battle impossible. On 28 August, Pelagius sued for peace, sending an envoy to al-Kamil.

The Crusaders still had some leverage. Damietta was well-garrisoned and a naval squadron under fleet admiral Henry of Malta, and Sicilian chancellor Walter of Palearia and German imperial marshal Anselm of Justingen, had been sent by Frederick II. They offered the sultan withdrawal from Damietta and an eight-year truce in exchange for allowing the Crusader army to pass, the release of all prisoners, and the return of the relic of the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

. Prior to the formal surrender of Damietta, the two sides would maintain hostages, among them John of Brienne and Hermann of Salza for the Franks side and as-Salih Ayyub, son of al-Kamil, for Egypt.

The masters of the military orders were dispatched to Damietta with the news of the surrender. It was not well-received, with the Venetians attempting to gain control, but the eventual happened on 8 September 1221. The Crusader ships departed and the sultan entered the city. The Fifth Crusade was over.

Aftermath

The Fifth Crusade ended with nothing gained for the West, with much loss of life, resources and reputations. Most were bitter that offensive operations were begun prior to the arrival of the emperor's forces, and had opposed the treaty. Walter of Palearia was stripped of his possessions and sent into exile. Admiral Henry of Malta was imprisoned only to be pardoned later by Frederick II.John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Champag ...

demonstrated his inability to command an international army and was censured for essentially deserting the Crusade in 1220. Pelagius

Pelagius (; c. 354–418) was a British theologian known for promoting a system of doctrines (termed Pelagianism by his opponents) which emphasized human choice in salvation and denied original sin. Pelagius and his followers abhorred the moral ...

was accused of ineffectual leadership and a misguided view that led him to reject the sultan's peace offering. The greatest criticism was leveled at Frederick II, whose ambition clearly lay in Europe not the Holy Land. The Crusade was unable to even gain the return of the piece of the True Cross

The True Cross is the cross upon which Jesus was said to have been crucified, particularly as an object of religious veneration. There are no early accounts that the apostles or early Christians preserved the physical cross themselves, althoug ...

. The Egyptians could not find it and the Crusaders left empty-handed.

The failure of the Crusade caused an outpouring of anti-papal sentiment from the Occitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

poet Guilhem Figueira

Guillem or Guilhem Figueira or Figera was a Languedocian jongleur and troubadour from Toulouse active at the court of the Emperor Frederick II in the 1230s.Graham-Leigh, 30. He was a close associate of both Aimery de Pégulhan and Guillem Augier ...

. The more orthodox Gormonda de Monpeslier Na Gormonda de Monpeslier or Montpelher (floruit, fl. 1226–1229) was a trobairitz from Montpellier in Languedoc. Her lone surviving work, a ''sirventes'', has been called "the first French political poem by a woman."Städtler, 129.

She wrote ...

responded to Figueira's ''D'un sirventes far'' with a song of her own, ''Greu m'es a durar''. Instead of blaming Pelagius or the Papacy, she laid the blame on the "foolishness" of the wicked. The '' Palästinalied'' is a famous lyric poem by Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (c. 1170c. 1230) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs (" Sprüche") in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundr ...

written in Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. Hig ...

describing a pilgrim travelling to the Holy Land during the height of the Fifth Crusade.

Participants

A partial list of those that participated in the Fifth Crusade can be found in the category collections ofChristians of the Fifth Crusade

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρισ ...

and Muslims of the Fifth Crusade.

Historiography

Thehistoriography