Bosnia and Herzegovina on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and

The

The  In the

In the

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.

Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.

Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous

A Brief History of Bosnia–Herzegovina

. The Bosnian Manuscript Ingathering Project. Bosnian recruits formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles of However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of the Great Turkish War with the

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of the Great Turkish War with the

Habsburg rule had several key concerns in Bosnia. It tried to dissipate the South Slav nationalism by disputing the earlier Serb and Croat claims to Bosnia and encouraging identification of Bosnian or Bosniak identity. Habsburg rule also tried to provide for modernisation by codifying laws, introducing new political institutions, establishing and expanding industries.

Austria–Hungary began to plan the annexation of Bosnia, but due to international disputes the issue was not resolved until the annexation crisis of 1908. Several external matters affected the status of Bosnia and its relationship with Austria–Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia in 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade. Then in 1908, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns that the

Habsburg rule had several key concerns in Bosnia. It tried to dissipate the South Slav nationalism by disputing the earlier Serb and Croat claims to Bosnia and encouraging identification of Bosnian or Bosniak identity. Habsburg rule also tried to provide for modernisation by codifying laws, introducing new political institutions, establishing and expanding industries.

Austria–Hungary began to plan the annexation of Bosnia, but due to international disputes the issue was not resolved until the annexation crisis of 1908. Several external matters affected the status of Bosnia and its relationship with Austria–Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia in 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade. Then in 1908, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns that the

Following World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the South Slav

Following World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the South Slav

Once the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by German forces in

Once the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by German forces in  A percentage of Muslims served in Nazi ''Waffen-SS'' units. These units were responsible for massacres of Serbs in northwest and eastern Bosnia, most notably in

A percentage of Muslims served in Nazi ''Waffen-SS'' units. These units were responsible for massacres of Serbs in northwest and eastern Bosnia, most notably in

Due to its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor in the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was relatively peaceful and very prosperous, with high employment, a strong industrial and export oriented economy, a good education system and social and medical security for every citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Several international corporations operated in Bosnia —

Due to its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor in the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was relatively peaceful and very prosperous, with high employment, a strong industrial and export oriented economy, a good education system and social and medical security for every citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Several international corporations operated in Bosnia —

Branko Mikulic – socialist emperor manqué

. BH Dani Their efforts proved key during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980, and are today considered some of the early steps towards Bosnian independence. However, the republic did not escape the increasingly nationalistic climate of the time. With the fall of communism and the start of the breakup of Yugoslavia, doctrine of tolerance began to lose its potency, creating an opportunity for nationalist elements in the society to spread their influence.

On 18 November 1990, multi-party parliamentary elections were held throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. A second round followed on 25 November, resulting in a

On 18 November 1990, multi-party parliamentary elections were held throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. A second round followed on 25 November, resulting in a  A declaration of the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 15 October 1991 was followed by a referendum for independence on 29 February and 1 March 1992, which was boycotted by the great majority of Serbs. The turnout in the independence referendum was 63.4 percent and 99.7 percent of voters voted for independence. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on 6 April 1992. The

A declaration of the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 15 October 1991 was followed by a referendum for independence on 29 February and 1 March 1992, which was boycotted by the great majority of Serbs. The turnout in the independence referendum was 63.4 percent and 99.7 percent of voters voted for independence. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on 6 April 1992. The

On 4 February 2014, the

On 4 February 2014, the

, ''

, ''britannica.com'', 9 September 2015 around the town of Neum in the

As a result of the

As a result of the

Final hearing of the Arbitration Tribunal in Vienna

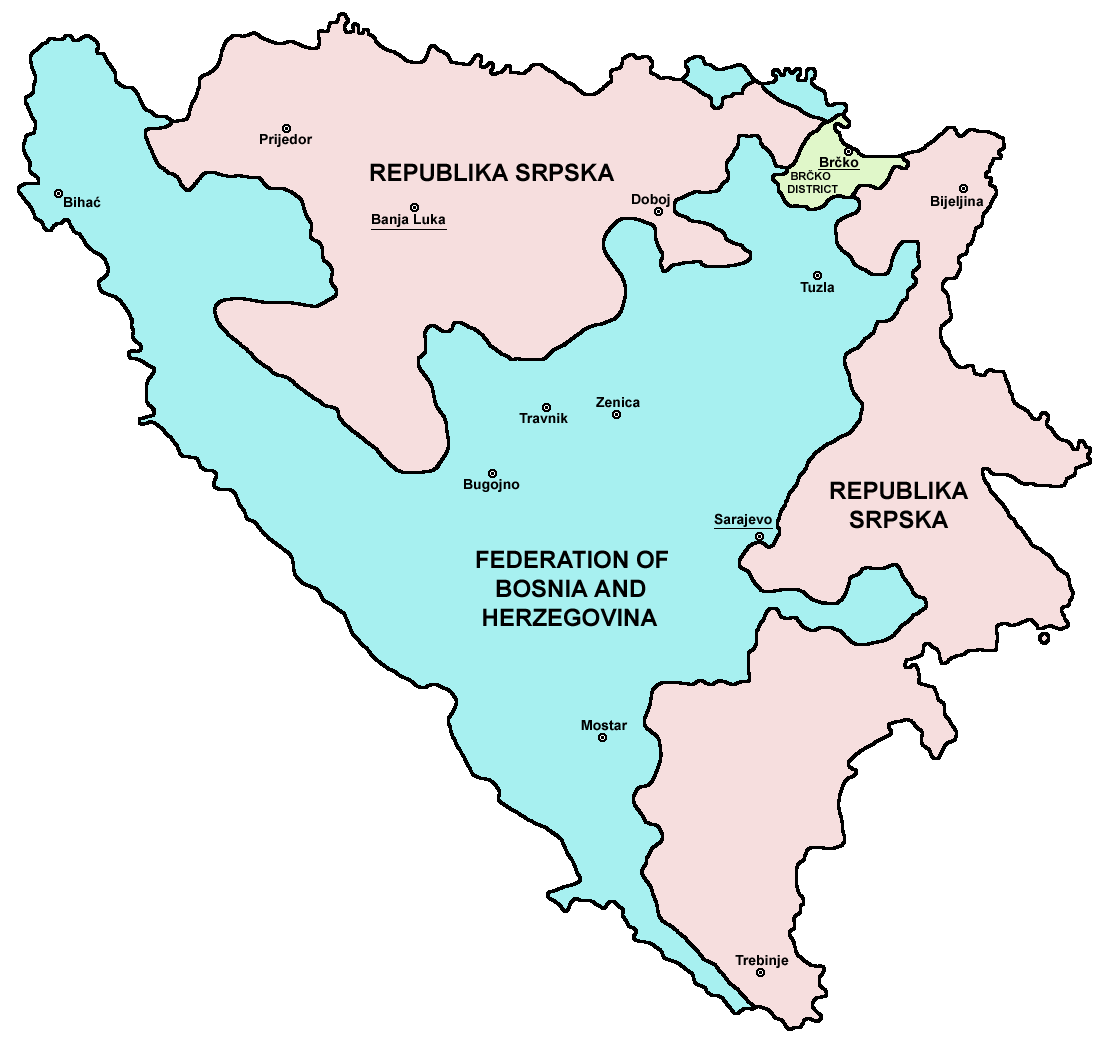

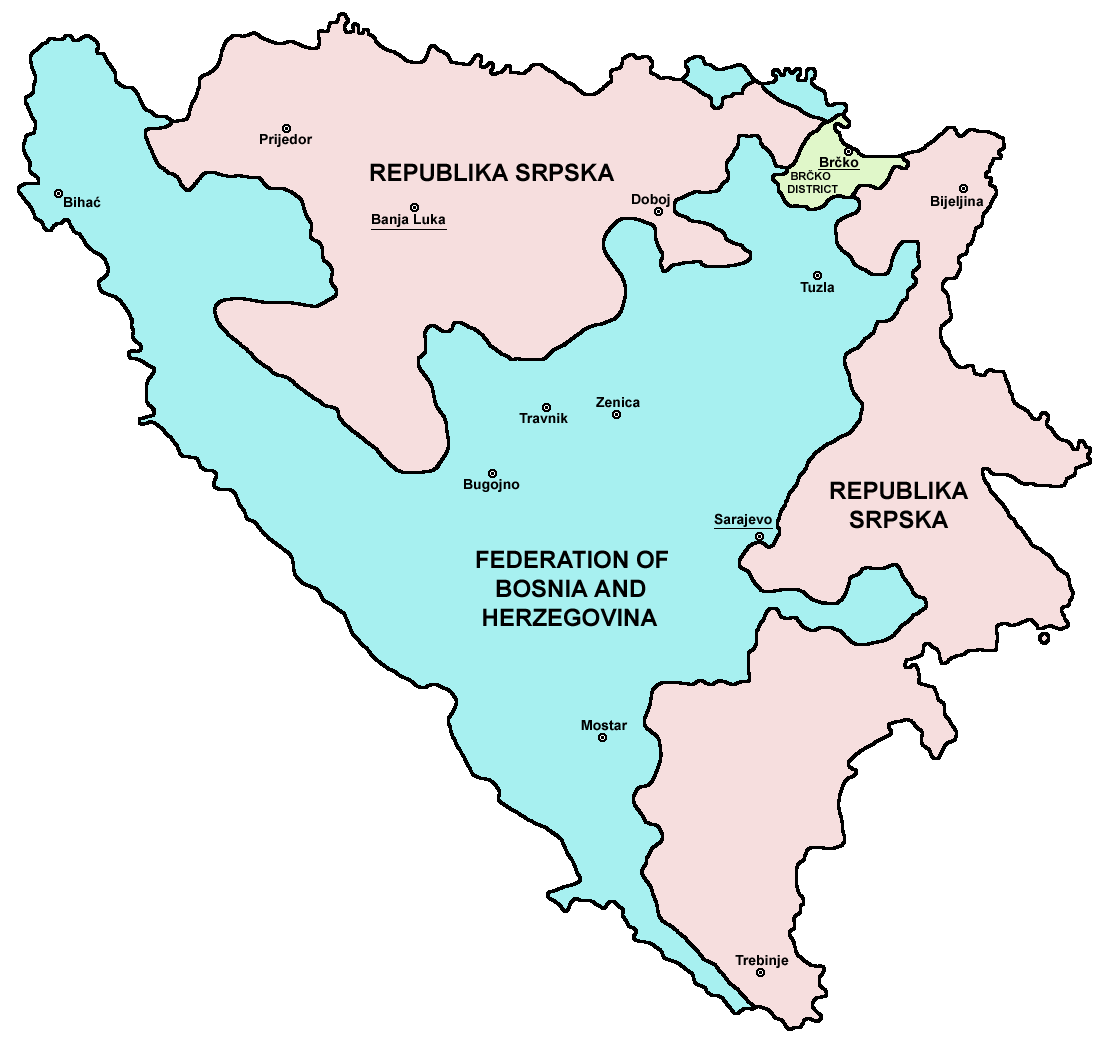

. OHR. The third level of Bosnia and Herzegovina's political subdivision is manifested in

During the Bosnian War, the economy suffered €200 billion in material damages, roughly €326.38 billion in 2022 (inflation adjusted). Bosnia and Herzegovina faces the dual-problem of rebuilding a war-torn country and introducing transitional liberal market reforms to its formerly mixed economy. One legacy of the previous era is a strong industry; under former republic president Džemal Bijedić and Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, metal industries were promoted in the republic, resulting in the development of a large share of Yugoslavia's plants;

During the Bosnian War, the economy suffered €200 billion in material damages, roughly €326.38 billion in 2022 (inflation adjusted). Bosnia and Herzegovina faces the dual-problem of rebuilding a war-torn country and introducing transitional liberal market reforms to its formerly mixed economy. One legacy of the previous era is a strong industry; under former republic president Džemal Bijedić and Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, metal industries were promoted in the republic, resulting in the development of a large share of Yugoslavia's plants;  In 2018, the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina made a profit of 8,430,875 km (€4,306,347).

The World Bank predicted that the economy would grow 3.4% in 2019.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was placed 83rd on the Index of Economic Freedom for 2019. The total rating for Bosnia and Herzegovina is 61.9. This position represents some progress relative to the 91st place in 2018. This result is below the regional level, but still above the global average, making Bosnia and Herzegovina a "moderately free" country.

On 31 January 2019, total deposits in Bosnian banks were KM 21.9 billion (€11.20 billion), which represents 61.15% of nominal GDP.

In the second quarter of 2019, the average price of new apartments sold in Bosnia and Herzegovina was 1,606 km (€821.47) per square metre.

In the first six months of 2019, exports amounted to 5.829 billion KM (€2.98 billion), which is 0.1% less than in the same period of 2018, while imports amounted to 9.779 billion KM (€5.00 billion), which is by 4.5% more than in the same period of the previous year.

In the first six months of 2019, foreign direct investment amounted to 650.1 million KM (€332.34 million).

Bosnia and Herzegovina was ranked 75th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.

In 2018, the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina made a profit of 8,430,875 km (€4,306,347).

The World Bank predicted that the economy would grow 3.4% in 2019.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was placed 83rd on the Index of Economic Freedom for 2019. The total rating for Bosnia and Herzegovina is 61.9. This position represents some progress relative to the 91st place in 2018. This result is below the regional level, but still above the global average, making Bosnia and Herzegovina a "moderately free" country.

On 31 January 2019, total deposits in Bosnian banks were KM 21.9 billion (€11.20 billion), which represents 61.15% of nominal GDP.

In the second quarter of 2019, the average price of new apartments sold in Bosnia and Herzegovina was 1,606 km (€821.47) per square metre.

In the first six months of 2019, exports amounted to 5.829 billion KM (€2.98 billion), which is 0.1% less than in the same period of 2018, while imports amounted to 9.779 billion KM (€5.00 billion), which is by 4.5% more than in the same period of the previous year.

In the first six months of 2019, foreign direct investment amounted to 650.1 million KM (€332.34 million).

Bosnia and Herzegovina was ranked 75th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.

, Reuters.com; retrieved 17 March 2010. Since 2019, pilgrimages to Međugorje have been officially authorized and organized by the Holy See, Vatican. Bosnia has also become an increasingly popular skiing and Ecotourism destination. The mountains that hosted the winter olympic games of

, The central Dinaric Alps, Bosnian Dinaric Alps are favored by hikers and mountaineers, as they contain both Mediterranean climate, Mediterranean and Alpine climate, Alpine climates. Rafting, Whitewater rafting has become somewhat of a national sport, national pastime in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The primary rivers used for whitewater rafting in the country include the Vrbas (river), Vrbas, Tara (river), Tara, Drina, Neretva and Una (Sava), Una. Meanwhile, the most prominent rivers are the Vrbas and Tara, as they both hosted International Rafting Federation, The 2009 World Rafting Championship. The reason the Tara river is immensely popular for whitewater rafting is because it contains the deepest canyon, river canyon in Europe, the Tara River Canyon. Most recently, the ''HuffPost, Huffington Post'' named Bosnia and Herzegovina the "9th Greatest Adventure in the World for 2013", adding that the country boasts "the cleanest water and air in Europe; the greatest untouched forests; and the most wildlife. The best way to experience is the three rivers trip, which purls through the best the Balkans have to offer."

Sarajevo International Airport, also known as Butmir Airport, is the main international airport in Bosnia and Herzegovina, located southwest of the Sarajevo main railway station in the city of

Sarajevo International Airport, also known as Butmir Airport, is the main international airport in Bosnia and Herzegovina, located southwest of the Sarajevo main railway station in the city of

Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Higher education has a long and rich tradition in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first bespoke higher-education institution was a school of Sufi philosophy established by

Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Higher education has a long and rich tradition in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first bespoke higher-education institution was a school of Sufi philosophy established by

Bosnia and Herzegovina

", EJC Media Landscapes Post-war developments included the establishment of an independent Communication Regulatory Agency, the adoption of a Press Code, the establishment of the Press Council, the decriminalization of libel and defamation, the introduction of a rather advanced Freedom of Access to Information Law, and the creation of a Public Service Broadcasting System from the formerly state-owned broadcaster. Yet, internationally backed positive developments have been often obstructed by domestic elites, and the professionalisation of media and journalists has proceeded only slowly. High levels of partisanship and linkages between the media and the political systems hinder the adherence to professional code of conducts.

The Bosnia and Herzegovina art, art of Bosnia and Herzegovina was always evolving and ranged from the original medieval tombstones called Steƒáak, Steƒáci to paintings in Kotromaniƒá court. However, only with the arrival of Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarians did the painting renaissance in Bosnia really begin to flourish. The first educated artists from European academies appeared with the beginning of the 20th century. Among those are: Gabrijel Jurkiƒá, Petar ≈Ýain, Roman Petroviƒá and Lazar Drljaƒça.

After

The Bosnia and Herzegovina art, art of Bosnia and Herzegovina was always evolving and ranged from the original medieval tombstones called Steƒáak, Steƒáci to paintings in Kotromaniƒá court. However, only with the arrival of Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarians did the painting renaissance in Bosnia really begin to flourish. The first educated artists from European academies appeared with the beginning of the 20th century. Among those are: Gabrijel Jurkiƒá, Petar ≈Ýain, Roman Petroviƒá and Lazar Drljaƒça.

After

Typical Bosnian songs are ''Ganga (music), ganga, rera'', and the traditional Slavic music for the folk dances such as ''Kolo (dance), kolo'', while from the Ottoman era the most popular is Sevdalinka. Pop and Rock music has a tradition here as well, with the more famous musicians including Dino Zoniƒá, Goran Bregoviƒá, Davorin Popoviƒá, Kemal Monteno, Zdravko ƒåoliƒá, Elvir Lakoviƒá Laka, Edo Maajka, Hari Vare≈°anoviƒá, Dino Merlin, Mladen Vojiƒçiƒá Tifa, ≈Ωeljko Bebek, etc. Other composers such as ƒêorƒëe Novkoviƒá, Al' Dino, Haris D≈æinoviƒá, Kornelije Kovaƒç, and many Musical ensemble#Rock and pop bands, rock and pop bands, for example, Bijelo Dugme, Crvena jabuka, Divlje jagode, Indexi, Plavi orkestar, Zabranjeno Pu≈°enje, Ambasadori, Dubioza kolektiv, who were among the leading ones in the former Yugoslavia. Bosnia is home to the composer Du≈°an ≈Ýestiƒá, the creator of the National Anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovina and father of singer Marija ≈Ýestiƒá, to the world known jazz musician, educator and Bosnian jazz ambassador Sinan Alimanoviƒá, composer Sa≈°a Lo≈°iƒá and pianist Sa≈°a Toperiƒá. In the villages, especially in Herzegovina, Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats play the ancient gusle. The gusle is used mainly to recite epic poems in a usually dramatic tone.

Probably the most distinctive and identifiably "Bosnian" of music, Sevdalinka is a kind of emotional, melancholic folk song that often describes sad subjects such as love and loss, the death of a dear person or heartbreak. Sevdalinkas were traditionally performed with a Bağlama, saz, a Turkish string instrument, which was later replaced by the accordion. However the more modern arrangement, to the derision of some purists, is typically a vocalist accompanied by the accordion along with snare drums, upright bass, guitars, clarinets and violins.

Rural folk traditions in Bosnia and Herzegovina include the shouted, polyphony, polyphonic ganga and "ravne pjesme" (''flat song'') styles, as well as instruments like a droneless Bagpipes, bagpipe, wooden flute and šargija. The gusle, an instrument found throughout the

Typical Bosnian songs are ''Ganga (music), ganga, rera'', and the traditional Slavic music for the folk dances such as ''Kolo (dance), kolo'', while from the Ottoman era the most popular is Sevdalinka. Pop and Rock music has a tradition here as well, with the more famous musicians including Dino Zoniƒá, Goran Bregoviƒá, Davorin Popoviƒá, Kemal Monteno, Zdravko ƒåoliƒá, Elvir Lakoviƒá Laka, Edo Maajka, Hari Vare≈°anoviƒá, Dino Merlin, Mladen Vojiƒçiƒá Tifa, ≈Ωeljko Bebek, etc. Other composers such as ƒêorƒëe Novkoviƒá, Al' Dino, Haris D≈æinoviƒá, Kornelije Kovaƒç, and many Musical ensemble#Rock and pop bands, rock and pop bands, for example, Bijelo Dugme, Crvena jabuka, Divlje jagode, Indexi, Plavi orkestar, Zabranjeno Pu≈°enje, Ambasadori, Dubioza kolektiv, who were among the leading ones in the former Yugoslavia. Bosnia is home to the composer Du≈°an ≈Ýestiƒá, the creator of the National Anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovina and father of singer Marija ≈Ýestiƒá, to the world known jazz musician, educator and Bosnian jazz ambassador Sinan Alimanoviƒá, composer Sa≈°a Lo≈°iƒá and pianist Sa≈°a Toperiƒá. In the villages, especially in Herzegovina, Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats play the ancient gusle. The gusle is used mainly to recite epic poems in a usually dramatic tone.

Probably the most distinctive and identifiably "Bosnian" of music, Sevdalinka is a kind of emotional, melancholic folk song that often describes sad subjects such as love and loss, the death of a dear person or heartbreak. Sevdalinkas were traditionally performed with a Bağlama, saz, a Turkish string instrument, which was later replaced by the accordion. However the more modern arrangement, to the derision of some purists, is typically a vocalist accompanied by the accordion along with snare drums, upright bass, guitars, clarinets and violins.

Rural folk traditions in Bosnia and Herzegovina include the shouted, polyphony, polyphonic ganga and "ravne pjesme" (''flat song'') styles, as well as instruments like a droneless Bagpipes, bagpipe, wooden flute and šargija. The gusle, an instrument found throughout the

Bosnian cuisine uses many spices, in moderate quantities. Most dishes are light, as they are boiled; the sauces are fully natural, consisting of little more than the natural juices of the vegetables in the dish. Typical ingredients include tomatoes, potatoes, onions, garlic, Capsicum, peppers, cucumbers, carrots, cabbage, mushrooms, spinach, zucchini, bean, dried beans, fresh beans, plums, milk, paprika and cream called Smetana (dairy product), pavlaka. Bosnian cuisine is balanced between Western culture, Western and Eastern world, Eastern influences. As a result of the Turkish cuisine, Ottoman administration for almost 500 years, Bosnian food is closely related to Turkish, Greek cuisine, Greek and other former Ottoman and Mediterranean cuisine, Mediterranean cuisines. However, because of years of Austrian rule, there are many influences from Central European cuisine, Central Europe. Typical meat dishes include primarily beef and Lamb and mutton, lamb. Some local specialties are ćevapi, Börek, burek, dolma, Sarma (food), sarma, Pilaf, pilav, goulash, ajvar and a whole range of Eastern sweets. Ćevapi is a grilled dish of minced meat, a type of kebab, popular in former Yugoslavia and considered a national dish in Bosnia and Herzegovina and

Bosnian cuisine uses many spices, in moderate quantities. Most dishes are light, as they are boiled; the sauces are fully natural, consisting of little more than the natural juices of the vegetables in the dish. Typical ingredients include tomatoes, potatoes, onions, garlic, Capsicum, peppers, cucumbers, carrots, cabbage, mushrooms, spinach, zucchini, bean, dried beans, fresh beans, plums, milk, paprika and cream called Smetana (dairy product), pavlaka. Bosnian cuisine is balanced between Western culture, Western and Eastern world, Eastern influences. As a result of the Turkish cuisine, Ottoman administration for almost 500 years, Bosnian food is closely related to Turkish, Greek cuisine, Greek and other former Ottoman and Mediterranean cuisine, Mediterranean cuisines. However, because of years of Austrian rule, there are many influences from Central European cuisine, Central Europe. Typical meat dishes include primarily beef and Lamb and mutton, lamb. Some local specialties are ćevapi, Börek, burek, dolma, Sarma (food), sarma, Pilaf, pilav, goulash, ajvar and a whole range of Eastern sweets. Ćevapi is a grilled dish of minced meat, a type of kebab, popular in former Yugoslavia and considered a national dish in Bosnia and Herzegovina and

Bosnia and Herzegovina has produced many athletes, both as a state in Yugoslavia and independently after 1992. The most important international Sport, sporting event in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina were the 1984 Winter Olympics, 14th Winter Olympics, held in

Bosnia and Herzegovina has produced many athletes, both as a state in Yugoslavia and independently after 1992. The most important international Sport, sporting event in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina were the 1984 Winter Olympics, 14th Winter Olympics, held in  Association football is the most popular sport in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It dates from 1903, but its popularity grew significantly after

Association football is the most popular sport in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It dates from 1903, but its popularity grew significantly after

Bosnia and Herzegovina

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs'' * * {{Authority control Bosnia and Herzegovina, Balkan countries Bosnian-speaking countries and territories Croatian-speaking countries and territories Federal republics Member states of the Council of Europe Member states of the Union for the Mediterranean Member states of the United Nations Serbian-speaking countries and territories Southeastern European countries Southern European countries States and territories established in 1992 Countries in Europe Observer states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

, located in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. Bosnia and Herzegovina borders Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

to the east, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

to the southeast, and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

to the north and southwest. In the south it has a narrow coast on the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

within the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, which is about long and surrounds the town of Neum

Neum ( cyrl, –ù–µ—É–º, ) is a town and municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the only town to be situated along the Bosnia and Herzegovina's coastline, m ...

. Bosnia, which is the inland region of the country, has a moderate continental climate with hot summers and cold, snowy winters. In the central and eastern regions of the country, the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and in the northeast it is predominantly flat. Herzegovina, which is the smaller, southern region of the country, has a Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

and is mostly mountainous. Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, –°–∞—Ä–∞—ò–µ–≤–æ, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

is the capital and the largest city of the country followed by Banja Luka

Banja Luka ( sr-Cyrl, –ë–∞—ö–∞ –õ—É–∫–∞, ) or Banjaluka ( sr-Cyrl, –ë–∞—ö–∞–ª—É–∫–∞, ) is the second largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the largest city of Republika Srpska. Banja Luka is also the ''de facto'' capital of this entity. I ...

, Tuzla

Tuzla (, ) is the third-largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the administrative center of Tuzla Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, it has a population of 110,979 inhabitants.

Tuzla is the economic, cultural, e ...

and Zenica

Zenica ( ; ; ) is a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and an administrative and economic center of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina's Zenica-Doboj Canton. It is located in the Bosna river valley, about north of Sarajevo. The city is k ...

.

The area that is now Bosnia and Herzegovina has been inhabited by human beings since at least the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

, but evidence suggests that during the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

age, permanent human settlements were established, including those that belonged to the Butmir

Butmir ( sr-cyrl, Бутмир) is a neighborhood in Ilidža municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo International Airport, the main airport of Bosnia and Herzegovina is located in Butmir.

Horse races are held at Butmir.Archived aGhosta ...

, Kakanj, and Vučedol

Vučedol () is an archeological site, an elevated ground on the right bank of the river Danube near Vukovar that became the eponym of the eneolithic Vučedol culture.

It is estimated that the site had once been home to about 3,000 inhabitants, mak ...

cultures. After the arrival of the first Indo-Europeans, the area was populated by several Illyrian and Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

civilizations. Culturally, politically, and socially, the country has a rich and complex history. The ancestors of the South Slavic peoples that populate the area today arrived during the 6th through the 9th century. In the 12th century, the Banate of Bosnia was established; by the 14th century, this had evolved into the Kingdom of Bosnia. In the mid-15th century, it was annexed into the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, under whose rule it remained until the late 19th century. The Ottomans brought Islam to the region, and altered much of the country's cultural and social outlook.

From the late 19th century until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the country was annexed into the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In the interwar period, Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, –ö—Ä–∞—ô–µ–≤–∏–Ω–∞ –à—É–≥–æ—Å–ª–∞–≤–∏—ò–∞; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 ...

. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, it was granted full republic status in the newly formed Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

. In 1992, following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the republic proclaimed independence. This was followed by the Bosnian War, which lasted until late 1995 and was brought to a close with the signing of the Dayton Agreement

The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, also known as the Dayton Agreement or the Dayton Accords ( Croatian: ''Daytonski sporazum'', Serbian and Bosnian: ''Dejtonski mirovni sporazum'' / –î–µ—ò—Ç–æ–Ω—Å–∫–∏ –º–∏—Ä–æ ...

.

Today, the country is home to three main ethnic groups

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

, designated "constituent peoples" in the country's constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. The Bosniaks are the largest group of the three, the Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, –°—Ä–±–∏, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

are the second-largest, and the Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, ...

are the third-largest. In English, all natives of Bosnia and Herzegovina, regardless of ethnicity, are called Bosnian. Minorities, who under the constitution are categorized as "others", include Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

, Albanians, Montenegrins, Ukrainians and Turks.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a bicameral legislature and a three-member presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified b ...

made up of one member from each of the three major ethnic groups. However, the central government's power is highly limited, as the country is largely decentralized. It comprises two autonomous entities—the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska

Republika Srpska ( sr-Cyrl, –Ý–µ–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –°—Ä–ø—Å–∫–∞, lit=Serb Republic, also known as Republic of Srpska, ) is one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is locat ...

—and a third unit, the Brčko District

Brčko District ( bs, Brčko Distrikt; hr, Brčko Distrikt; sr, Брчко Дистрикт, ), officially the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( bs, Brčko Distrikt Bosne i Hercegovine; hr, Brčko Distrikt Bosne i Hercegovine; ), i ...

, which is governed by its own local government. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina furthermore consists of 10 cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, t ...

.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a developing country and ranks 74th in the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, wh ...

. Its economy is dominated by industry and agriculture, followed by tourism and the service sector. Tourism has increased significantly in recent years. The country has a social-security and universal-healthcare system, and primary and secondary level education is free. It is a member of the UN, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is the world's largest regional security-oriented intergovernmental organization with observer status at the United Nations. Its mandate includes issues such as arms control, pro ...

, the Council of Europe, the Partnership for Peace

The Partnership for Peace (PfP; french: Partenariat pour la paix) is a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) program aimed at creating trust between the member states of NATO and other states mostly in Europe, including post-Soviet state ...

, and the Central European Free Trade Agreement

The Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) is an international trade agreement between countries mostly located in Southeastern Europe. Founded by representatives of Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, CEFTA expanded to Albania, Bosnia ...

; it is also a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM; french: Union pour la Méditerranée, ar, الإتحاد من أجل المتوسط ''Al-Ittiḥād min ajl al-Mutawasseṭ'') is an intergovernmental organization of 43 member states from Europe and the M ...

, established in July 2008. Bosnia and Herzegovina is an EU candidate country and has also been a candidate for NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

membership since April 2010, when it received a Membership Action Plan.

Etymology

The first preserved widely acknowledged mention of a form of the name " Bosnia" is in '' De Administrando Imperio'', a politico-geographical handbook written by theByzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Byzantine Empire, Eastern Roman Empire, to Fall of Constantinople, its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. On ...

Constantine VII in the mid-10th century (between 948 and 952) describing the "small land" (χωρίον in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) of "Bosona" (Βοσώνα), where the Serbs dwell.

The name is believed to derive from the hydronym

A hydronym (from el, ὕδρω, , "water" and , , "name") is a type of toponym that designates a proper name of a body of water. Hydronyms include the proper names of rivers and streams, lakes and ponds, swamps and marshes, seas and oceans. As ...

of the river Bosna that courses through the Bosnian heartland. According to philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

Anton Mayer, the name ''Bosna'' could derive from Illyrian *"Bass-an-as", which in turn could derive from the Proto-Indo-European root "bos" or "bogh", meaning "the running water". According to the English medievalist William Miller, the Slavic settlers in Bosnia "adapted the Latin designation ... Basante, to their own idiom by calling the stream Bosna and themselves ''Bosniaks''".

The name ''Herzegovina'' means "herzog's and

or AND may refer to:

Logic, grammar, and computing

* Conjunction (grammar), connecting two words, phrases, or clauses

* Logical conjunction in mathematical logic, notated as "‚àß", "‚ãÖ", "&", or simple juxtaposition

* Bitwise AND, a boolea ...

, and "herzog" derives from the German word for "duke". It originates from the title of a 15th-century Bosnian magnate, Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, who was "Herceg erzogof Hum and the Coast" (1448). Hum (formerly called Zachlumia

Zachlumia or Zachumlia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Zahumlje, –ó–∞—Ö—É–º—ô–µ, ), also Hum, was a medieval principality located in the modern-day regions of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia (today parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia ...

) was an early medieval principality that had been conquered by the Bosnian Banate in the first half of the 14th century. When the Ottomans took over administration of the region, they called it the Sanjak of Herzegovina

The Sanjak of Herzegovina ( tr, Hersek Sancağı; sh, Hercegovački sandžak) was an Ottoman administrative unit established in 1470. The seat was in Foča until 1572 when it was moved to Taşlıca (Pljevlja). The sanjak was initially part of ...

(''Hersek''). It was included within the Bosnia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based o ...

until the formation of the short-lived Herzegovina Eyalet in the 1830s, which reemerged in the 1850s, after which the administrative region became commonly known as ''Bosnia and Herzegovina''.

On initial proclamation of independence in 1992, the country's official name was the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Republika Bosna i Hercegovina, –Ý–µ–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–æ—Å–Ω–∞ –∏ –•–µ—Ä—Ü–µ–≥–æ–≤–∏–Ω–∞) was a state in Southeastern Europe, existing from 1992 to 1995. It is the direct lega ...

, but following the 1995 Dayton Agreement

The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, also known as the Dayton Agreement or the Dayton Accords ( Croatian: ''Daytonski sporazum'', Serbian and Bosnian: ''Dejtonski mirovni sporazum'' / –î–µ—ò—Ç–æ–Ω—Å–∫–∏ –º–∏—Ä–æ ...

and the new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

that accompanied it, the official name was changed to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

History

Early history

Bosnia has been inhabited by humans since at least the Paleolithic, as one of the oldest cave paintings was found inBadanj cave

Badanj Cave ( Bosnian: ''Pećina Badanj'') is located in Borojevići village near the town of Stolac, Bosnia and Herzegovina. This rather small cave has come to public attention after the 1976 discovery of its cave engravings, that date to betwee ...

. Major Neolithic cultures such as the Butmir

Butmir ( sr-cyrl, Бутмир) is a neighborhood in Ilidža municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo International Airport, the main airport of Bosnia and Herzegovina is located in Butmir.

Horse races are held at Butmir.Archived aGhosta ...

and Kakanj were present along the river Bosna dated from –.

The bronze culture of the Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, a ...

, an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form, started to organize itself in today's Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

, Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, –ö–æ—Å–æ–≤–æ ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosov√´s, links=no; sr, –Ý–µ–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ö–æ—Å–æ–≤–æ, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

and Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

.

From 8th century BCE, Illyrian tribes evolved into kingdoms. The earliest recorded kingdom in Illyria (a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians, as recorded in classical antiquity) was the Enchele in the 8th century BCE. The era in which we observe other Illyrian kingdoms begins approximately at 400 BCE and ends at 167 BCE. The Autariatae under Pleurias (337 BCE) were considered to have been a kingdom. The Kingdom of the Ardiaei

The Ardiaei were an Illyrian people who resided in the territory of present-day Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia between the Adriatic coast on the south, Konjic on the north, along the Neretva river and its righ ...

(originally a tribe from the Neretva valley region) began at 230 BCE and ended at 167 BCE. The most notable Illyrian kingdoms and dynasties were those of Bardylis of the Dardani and of Agron of the Ardiaei who created the last and best-known Illyrian kingdom. Agron ruled over the Ardiaei and had extended his rule to other tribes as well.

From the 7th century BCE, bronze was replaced by iron, after which only jewelry and art objects were still made out of bronze. Illyrian tribes, under the influence of Hallstatt

Hallstatt ( , , ) is a small town in the district of Gmunden, in the Austrian state of Upper Austria. Situated between the southwestern shore of Hallstätter See and the steep slopes of the Dachstein massif, the town lies in the Salzkammergut ...

cultures to the north, formed regional centers that were slightly different. Parts of Central Bosnia were inhabited by the Daesitiates

Daesitiates were an Illyrian tribe that lived on the territory of today's central Bosnia, during the time of the Roman Republic. Along with the Maezaei, the Daesitiates were part of the western group of Pannonians in Roman Dalmatia. They were ...

tribe, most commonly associated with the Central Bosnian cultural group

Central Bosnian culture () was a Bronze and Iron Age cultural group. This group, which ranged over the areas of the upper and mid course of the rivers Vrbas (to Jajce) and Bosna (to Zenica, but not including the Sarajevo¬Ýplain), constituted an ...

. The Iron Age Glasinac-Mati culture

The Glasinac-Mati culture is an archaeological culture, which first developed during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age in the western Balkan Peninsula in an area which encompassed much of modern Albania to the south, Kosovo to the east, Monte ...

is associated with the Autariatae

The Autariatae or Autariatai (alternatively, Autariates; grc, Αὐταριᾶται, ''Autariatai''; la, Autariatae) were an Illyrian people that lived between the valleys of the Lim and the Tara, beyond the Accursed Mountains, and the v ...

tribe.

A very important role in their life was the cult of the dead, which is seen in their careful burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of their burial sites. In northern parts, there was a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the south the dead were buried in large stone or earth tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built ...

(natively called ''gromile'') that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 m wide and 5 m high. ''Japodian tribes'' had an affinity to decoration (heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze foil).

In the 4th century BCE, the first invasion of Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

is recorded. They brought the technique of the pottery wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, ...

, new types of fibulas and different bronze and iron belts. They only passed on their way to Greece, so their influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina is negligible. Celtic migrations displaced many Illyrian tribes from their former lands, but some Celtic and Illyrian tribes mixed. Concrete historical evidence for this period is scarce, but overall it appears the region was populated by a number of different peoples speaking distinct languages.

In the Neretva Delta

Neretva Delta is the river delta of the Neretva, a river that flows through Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and empties in the Adriatic Sea. The delta is a unique landscape in southern Croatia, and a wetland that is listed under the Ramsar ...

in the south, there was important Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

influence of the Illyrian Daors

Daorson (Ancient Greek: Δαορσών) was the capital of the Illyrian tribe of the Daorsi (Ancient Greek Δαόριζοι, Δαούρσιοι; Latin ''Daorsei''). The Daorsi lived in the valley of the Neretva River between 300 BC and 50 BC. The ...

tribe. Their capital was ''Daorson'' in Ošanići near Stolac

Stolac is an ancient city located in Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located in the region of Herzegovina. Stolac is one of the oldest cities in Bosnia and Herzego ...

. Daorson in the 4th century BCE was surrounded by megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic, 5 m high stonewalls (as large as those of Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. ...

in Greece), composed of large trapezoid stone blocks. Daors made unique bronze coins and sculptures.

Conflict between the Illyrians and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

started in 229 BCE, but Rome did not complete its annexation of the region until AD 9. It was precisely in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina that Rome fought one of the most difficult battles in its history since the Punic Wars, as described by the Roman historian Suetonius. This was the Roman campaign against Illyricum, known as ''Bellum Batonianum

The ( Latin for 'War of the Batos') was a military conflict fought in the Roman province of Illyricum in the 1st century AD, in which an alliance of native peoples of the two regions of Illyricum, Dalmatia and Pannonia, revolted against the R ...

''. The conflict arose after an attempt to recruit Illyrians, and a revolt spanned for four years (6–9 AD), after which they were subdued. In the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from the entire Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

settled among the Illyrians, and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.

Following the split of the Empire between 337 and 395 AD, Dalmatia and Pannonia became parts of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

. The region was conquered by the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

in 455 AD. It subsequently changed hands between the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

and the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

. By the 6th century, Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

had reconquered the area for the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Slavs overwhelmed the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries. Illyrian cultural traits were adopted by the South Slavs, as evidenced in certain customs and traditions, placenames, etc.

Middle Ages

The

The Early Slavs

The early Slavs were a diverse group of tribal societies who lived during the Migration Period and the Early Middle Ages (approximately the 5th to the 10th centuries AD) in Central and Eastern Europe and established the foundations for the S ...

raided the Western Balkans, including Bosnia, in the 6th and early 7th century (amid the Migration Period), and were composed of small tribal units drawn from a single Slavic confederation known to the Byzantines as the ''Sclaveni

The ' (in Latin) or ' (various forms in Greek, see below) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became the progenitors of modern South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byz ...

'' (whilst the related '' Antes'', roughly speaking, colonized the eastern portions of the Balkans).

Tribes recorded by the ethnonyms of "Serb" and "Croat" are described as a second, latter, migration of different people during the second quarter of the 7th century who do not seem to have been particularly numerous; these early "Serb" and "Croat" tribes, whose exact identity is subject to scholarly debate, came to predominate over the Slavs in the neighbouring regions. The bulk of Bosnia proper, however, appears to have been a territory between Serb and Croat rule. It is considered that the westernmost and parts of proper modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina were settled and ruled by Croats, while the easternmost parts by Serbs.

Bosnia is first mentioned ''as a land (horion Bosona)'' in Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus' '' De Administrando Imperio'' in the mid 10th century, at the end of a chapter (Chap. 32) entitled ''Of the Serbs and the country in which they now dwell''. This has been scholarly interpreted in several ways and used especially by the Serb national ideologists to prove Bosnia as originally a "Serb" land. Other scholars have asserted the inclusion of Bosnia into Chapter 32 to merely be the result of Serbian Grand Duke Časlav's temporary rule over Bosnia at the time, while also pointing out Porphyrogenitus does not say anywhere explicitly that Bosnia is a "Serb land". In fact, the very translation of the critical sentence where the word ''Bosona'' (Bosnia) appears is subject to varying interpretation. In time, Bosnia formed a unit under its own ruler, who called himself Bosnian. Bosnia, along with other territories, became part of Duklja

Duklja ( sh-Cyrl, Дукља; el, Διόκλεια, Diokleia; la, Dioclea) was a medieval South Slavic state which roughly encompassed the territories of modern-day southeastern Montenegro, from the Bay of Kotor in the west to the Bojana Riv ...

in the 11th century, although it retained its own nobility and institutions.

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

, political circumstance led to the area being contested between the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

and the Byzantine Empire. Following another shift of power between the two in the early 12th century, Bosnia found itself outside the control of both and emerged as the Banate of Bosnia (under the rule of local '' bans''). The first Bosnian ban known by name was Ban Borić }

References

Sources and further reading

;Books

*

*

*

*

*

*

;Journals

*

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ban Boric

Bans of Bosnia

12th-century rulers in Europe

12th-century Hungarian people

12th-century Bosnian people

Borićević dynast ...

. The second was Ban Kulin, whose rule marked the start of a controversy involving the Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=/, Crkva bosanska, –¶—Ä–∫–≤–∞ –ë–æ—Å–∞–Ω—Å–∫–∞) was a Christian church in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodo ...

– considered heretical by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. In response to Hungarian attempts to use church politics regarding the issue as a way to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders to renounce the heresy and embraced Catholicism in 1203. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions remained unchanged long after Kulin's death in 1204, waning only after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254. During this time, the population was called ''Dobri Bošnjani

(; / , / ; ), meaning ''Bosnians'', is the name originating from the Middle Ages, used for the inhabitants of Bosnia. The name is used and can be found in Bosnian written monuments from that period, appearing in Venetian sources as earliest ...

'' ("Good Bosnians"). The names Serb and Croat, though occasionally appearing in peripheral areas, were not used in Bosnia proper.

Bosnian history from then until the early 14th century was marked by a power struggle between the ≈Ýubiƒá and Kotromaniƒá families. This conflict came to an end in 1322, when Stephen II Kotromaniƒá

Stephen II ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, separator=" / ", Стефан II, Stjepan II) was the Bosnian Ban from 1314, but in reality from 1322 to 1353 together with his brother, Vladislav Kotromanić in 1326–1353. He was the son of Bosnian Ban Stephen I Ko ...

became ''Ban''. By the time of his death in 1353, he was successful in annexing territories to the north and west, as well as Zahumlje and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his ambitious nephew Tvrtko who, following a prolonged struggle with nobility and inter-family strife, gained full control of the country in 1367. By the year 1377, Bosnia was elevated into a kingdom with the coronation of Tvrtko as the first Bosnian King in Mile near Visoko

Visoko ( sr-cyrl, –í–∏—Å–æ–∫–æ, ) is a city located in the Zenica-Doboj Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, the municipality had a population of 39,938 inhabitants with 11,205 liv ...

in the Bosnian heartland.Anđelić Pavao, Krunidbena i grobna crkva bosanskih vladara u Milima (Arnautovićima) kod Visokog. Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja XXXIV/1979., Zemaljski muzej Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, 1980,183–247

Following his death in 1391 however, Bosnia fell into a long period of decline. The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

had started its conquest of Europe and posed a major threat to the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

throughout the first half of the 15th century. Finally, after decades of political and social instability, the Kingdom of Bosnia ceased to exist in 1463 after its conquest by the Ottoman Empire.

There was a general awareness in medieval Bosnia, at least amongst the nobles, that they shared a join state with Serbia and that they belong to the same ethnic group. That awareness diminished over time, due to differences in political and social development, but it was kept in Herzegovina and parts of Bosnia which were a part of Serbian state.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.

Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.

Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=/, Crkva bosanska, –¶—Ä–∫–≤–∞ –ë–æ—Å–∞–Ω—Å–∫–∞) was a Christian church in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodo ...

disappeared altogether (ostensibly by conversion of its members to Islam). The Ottomans referred to them as ''kristianlar'' while the Orthodox and Catholics were called ''gebir'' or ''kafir'', meaning "unbeliever". The Bosnian Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

(and the Catholic population as a whole) were protected by official imperial decrees and in accordance and full extent of Ottoman laws; however, in effect, these often merely affected arbitrary rule and behavior of powerful local elite.

As the Ottoman Empire continued their rule in the Balkans ( Rumelia), Bosnia was somewhat relieved of the pressures of being a frontier province, and experienced a period of general welfare. A number of cities, such as Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, –°–∞—Ä–∞—ò–µ–≤–æ, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

and Mostar

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline = Mostar (collage image).jpg

, image_caption = From top, left to right: A panoramic view of the heritage town site and the Neretva river from Lučki Bridge, Koski Mehmed Pasha ...

, were established and grew into regional centers of trade and urban culture and were then visited by Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

in 1648. Within these cities, various Ottoman Sultans financed the construction of many works of Bosnian architecture

The architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina is largely influenced by four major periods, when political and social changes determined the creation of distinct cultural and architectural habits of the region.

Medieval period

The medieval period in ...

such as the country's first library in Sarajevo, madrassas

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: ŸÖÿØÿ±ÿ≥ÿ© , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

, a school of Sufi philosophy

Sufi philosophy includes the schools of thought unique to Sufism, the mystical tradition within Islam, also termed as ''Tasawwuf'' or ''Faqr'' according to its adherents. Sufism and its philosophical tradition may be associated with both Sunni a ...

, and a clock tower (''Sahat Kula''), bridges such as the Stari Most

Stari Most ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Stari most, –°—Ç–∞—Ä–∏ –º–æ—Å—Ç, Old Bridge), also known as Mostar Bridge, is a rebuilt 16th-century Ottoman bridge in the city of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina that crosses the river Neretva and connects the two ...

, the Emperor's Mosque

The Emperor's Mosque ( Bosnian: ''Careva džamija'', Turkish: ''Hünkâr Camii'') is an important landmark in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, being the first mosque to be built (1457) after the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia. It is the largest sing ...

and the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque (, ) is a mosque in the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Built in the 16th century, it is the largest historical mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one of the most representative Ottoman structures in the Balkan ...

.

Furthermore, several Bosnian Muslims played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural and political history

Political history is the narrative and survey of political events, ideas, movements, organs of government, voters, parties and leaders. It is closely related to other fields of history, including diplomatic history, constitutional history, socia ...

during this time.Riedlmayer, Andras (1993)A Brief History of Bosnia–Herzegovina

. The Bosnian Manuscript Ingathering Project. Bosnian recruits formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles of

Moh√°cs

Mohács (; Croatian and Bunjevac: ''Mohač''; german: Mohatsch; sr, Мохач; tr, Mohaç) is a town in Baranya County, Hungary, on the right bank of the Danube.

Etymology

The name probably comes from the Slavic ''*Mъchačь'',''*Mocháč'': ...

and Krbava field, while numerous other Bosnians rose through the ranks of the Ottoman military to occupy the highest positions of power in the Empire, including admirals such as Matrakçı Nasuh

Nasuh bin Karagöz bin Abdullah el-Visokavi el-Bosnavî, commonly known as Matrakçı Nasuh (; ) for his competence in the combat sport of ''Matrak'' which was invented by himself, (also known as ''Nasuh el-Silâhî'', ''Nasuh the Swordsman'', ...

; generals such as Isa-Beg Ishaković, Gazi Husrev-beg

Gazi Husrev-beg ( ota, غازى خسرو بك, ''Gāzī Ḫusrev Beğ''; Modern Turkish: ''Gazi Hüsrev Bey''; 1480–1541) was an Ottoman Bosnian sanjak-bey (governor) of the Sanjak of Bosnia in 1521–1525, 1526–1534, and 1536–1541. He ...

, Telli Hasan Pasha

Hasan Predojević ( 1530 – 22 June 1593), also known as Telli Hasan Pasha ( tr, Telli Hasan Paşa), was the fifth Ottoman beylerbey ( vali) of Bosnia and a notable Ottoman Bosnian military commander, who led an invasion of the Habsburg Kingdo ...

and Sarı Süleyman Pasha

Sarı Süleyman Paşa ( sh, Sari Sulejman-paša; died 14 October 1687) was the grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 18 November 1685 to 18 September 1687.İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, Türkiye Yayınevi, İstanbul, 197 ...

; administrators such as Ferhad Pasha Sokolović

Ferhad Pasha Sokolović ( tr, Sokollu Ferhad Paşa, sh, Ferhad-paša Sokolović) (died 1586) was an Ottoman general and statesman from Bosnia. He was the last sanjak-bey of Bosnia and first beylerbey of Bosnia.

Origin

Born into the Sokolović ...

and Osman Gradaščević

Osman Gradaščević ( 1765–1812) or Captain Osman (''Osman-kapetan'') was an Ottoman Bosnian captain of the military captaincy of Gradačac, which he was in control of since 1765. During his rule he was one of the most powerful and richest c ...

; and Grand Vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

s such as the influential Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

and Damat Ibrahim Pasha

Damat Ibrahim Pasha ( tr, Damat İbrahim Paşa, sh, Damat Ibrahim-paša; 1517–1601) was an Ottoman military commander and statesman who held the office of grand vizier three times (the first time from 4 April to 27 October 1596; the second t ...

. Some Bosnians emerged as Sufi mystics, scholars such as Muhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi

Muhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi ( tr, Mehmet Hevayi Uskufi, born c. 1600 in Dobrnja near Tuzla, died after 1651) was a Bosnian poet and writer who used the Arebica script.

Uskufi is noted as the author of the first " Bosnian- Turkish" dictionary ...

, Ali Džabić

Ali Fehmi Džabić (1853 – 5 August 1918) was a mufti of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Džabić was a figure in the Fata Omanović case of 1899. He remained in Constantinople until his death in 1918.

References

Bosnian Muslims from t ...

; and poets in the Turkish, Albanian, Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, and Persian language

Persian (), also known by its endonym Farsi (, ', ), is a Western Iranian language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian subdivision of the Indo-European languages. Persian is a pluricentric language predominantly spoken a ...

s.Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod;

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of the Great Turkish War with the

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of the Great Turkish War with the treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by th ...

in 1699 again made Bosnia the Empire's westernmost province. The 18th century was marked by further military failures, numerous revolts within Bosnia, and several outbreaks of plague.

The Porte's efforts at modernizing the Ottoman state were met with distrust growing to hostility in Bosnia, where local aristocrats stood to lose much through the proposed Tanzimat reforms. This, combined with frustrations over territorial, political concessions in the north-east, and the plight of Slavic Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

refugees arriving from the Sanjak of Smederevo

The Sanjak of Smederevo ( tr, Semendire Sancağı; sr, / ), also known in historiography as the Pashalik of Belgrade ( tr, Belgrad Paşalığı; sr, / ), was an Ottoman administrative unit (sanjak), that existed between the 15th and the out ...

into Bosnia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based o ...

, culminated in a partially unsuccessful revolt by Husein Gradaščević

Husein Grada≈°ƒçeviƒá (''Husein-kapetan'') (31 August 1802 ‚Äì 17 August 1834) was a Bosnian military commander who later led a rebellion against the Ottoman government, seeking autonomy for Bosnia. Born into a Bosnian noble family, Grada≈°ƒ ...

, who endorsed a Bosnia Eyalet autonomous from the authoritarian rule of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, ŸÖÿ≠ŸÖŸàÿØ ÿ´ÿߟܟâ, Ma·∏•m√ªd-u sÃÝ√¢n√Æ, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 ‚Äì 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

, who persecuted, executed and abolished the Janissaries and reduced the role of autonomous Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignitar ...

s in Rumelia. Mahmud II sent his Grand vizier to subdue Bosnia Eyalet and succeeded only with the reluctant assistance of Ali Pasha Rizvanbegović

Ali Pasha Rizvanbegović (1783 – 20 March 1851; Turkish: Ali Paşa Rıdvanbegoviç) was a Herzegovinian Ottoman captain (administrator) of Stolac from 1813 to 1833 and the semi-independent ruler (vizier) of the Herzegovina Eyalet from 1833 t ...

. Related rebellions were extinguished by 1850, but the situation continued to deteriorate.

New nationalist movements appeared in Bosnia by the middle of the 19th century. Shortly after Serbia's breakaway from the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, Serbian and Croatian nationalism rose up in Bosnia, and such nationalists made irredentist claims to Bosnia's territory. This trend continued to grow in the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Agrarian unrest eventually sparked the Herzegovinian rebellion, a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, a situation that led to the Congress of Berlin